Tiger, Tiger!

Tigers are deeply embedded in the cultural and natural heritage of India. They feature prominently in Mughal history and Hindu, Jain, Sikh and Buddhist thought and are associated with deities, royals and epic stories.

Their symbolism extends to various aspects of Indian heritage: mythology, folklore and art, as well as religious practices. Discover history, myth and folklore of the Bengal Tiger also known as Panthera tigris tigris.

In this Article

I first came under the tiger’s spell in Ranthambhore National Park, it was freezing cold, early in the morning and I remember “Tiger! Tiger!”

And there they were.

Fighting – fierce and fast – and both went off, into different directions.

Excitement takes over – I transform into a professional wildlife photographer having the perfect shot in front of me – except it’s blurry, my hands were shaking.

Tiger safaris are a mix of adrenaline, patience, and unexpected humor. Whether you see a tiger or just a lot of enthusiastic tourists, it’s always an adventure!

Our guide Fateh explained: ”It is Riddhi & Siddhi ( T 124 & T 125 ), daughters of Tigress Arrowhead ( T 84 ), the lady of lake. The sisters are fighting for territory around Padam Lake, the largest water body in the Ranthambhore Wildlife Reserve. This beautiful lake is the main source of water for the animals in the reserve.”

Struck by that experience I continue to remember it vividly. Tigers still live in our memories: wide-eyed cubs and huge males we were fortunate to encounter across the wild heart of India.

“Tyger! Tyger! Burning Bright

In the forests of the night

What immortal hand or eye

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?”

Blake’s original printing of The Tyger, 1794. The William Blake Archive.

Public domain,edited.

With their regal presence and fierce charisma, these majestic creatures inspire awe and respect unlike anything else. Inscrutable, both admired and feared for its power, strength, and beauty, as phrased in the timeless poem by William Blake.

Listen how the tiger (Panthera tigris Linnaeus, 1758) growls and roars:

The Bengal tiger, formerly known as Royal Bengal tiger, belongs to the population of the Panthera tigris tigris subspecies, native to the Indian subcontinent. It is considered to be one of the largest carnivore mammals alive today and is the national animal of both India and Bangladesh.

The gentleman of the jungle

“Tiger!”—only for everyone to turn and realize it’s just a striped log, a rock, or even a distant deer. We eagerly stare into the dense foliage for hours, convinced we’ll spot a tiger. Meanwhile, the predator is probably lounging just a few meters away, camouflaged perfectly.

“Don’t be disappointed if you could not see the tiger, the tiger sure would have seen you”.

wildlife wardens words

The tiger avoids contact with people and will hide away, hence their nickname of “The Gentleman of the Jungle”. This is also one of the major survival techniques adopted by the predator.

Unlike the lion, the Bengal Tiger leads a very solitary life, hunts alone, lives and replicates in the areas that provide him enough cover. But there is a catch. While a tiger lies in the bush it stays perfectly still without a sound. Except for its tail, which he can never hold still however hard it tries.

Valmik Thapar writes in Living with tigers, 2016:

“I have to admit that observing tigers in the wild must surely be one of the most time-consuming activities in the field of natural history. It requires infinite patience and perseverance—not only when the tiger is nowhere to be found but even when he is right there in front of you. […]

For 80 per cent of the time the tiger sits or sleeps; dozing in a shady strategically placed spot in the day, occasionally getting up to stretch or to watch a group of deer or peacocks pass by in the distance.[…]

For 10 per cent of the time that they are awake they walk on man-made paths and animal tracks hoping to bump into prey and at the same time patrol their areas. The remaining 10 per cent of their ‘awake time’ constitutes everything enthralling about the tiger’s life.[…]”

Historic and present Tiger habitat

There are two subspecies of tiger, commonly referred to as the Continental tiger and the Sunda island tiger, the Sumatra (Panthera tigris sumatrae).

The continental tigers currently include the Bengal (Panthera tigris sondaica), Malayan (Panthera tigris jacksoni), Indochinese (Panthera tigris corbetti), and Amur or Siberian (Panthera tigris altaica) populations. The South China tiger (Pantheratigris amoyensis) is believed to be functionally extinct. Also the Bali, Caspian and Javan subspecies are now extinct.

The Bengal Tiger (Panthera tigris tigris), is found throughout India except in the north-western region and also in the neighboring countries, Nepal, Bhutan and Bangladesh. Presently, tigers are found in a variety of habitats across South and Southeast Asia, China and Eastern Russia.

The royal tiger hunt

The tiger and the lion have in India the same dignity, and are both supreme symbols of royal strength and majesty/ The tiger of men and the lion of men are two expressions equivalent to prince, as the prince is supposed to be the best man.

It is strength that gives victory and superiority in natural relations; therefore the tiger and the lion, called kings of beasts, represent the king in the civic social relations among men. The narasinhas of India was called, in the Middle Ages, the king par excellence.

De Gubernatis Angelo. Zoological Mythology, or, The Legends of Animals, Vol. 1-2. 1872.

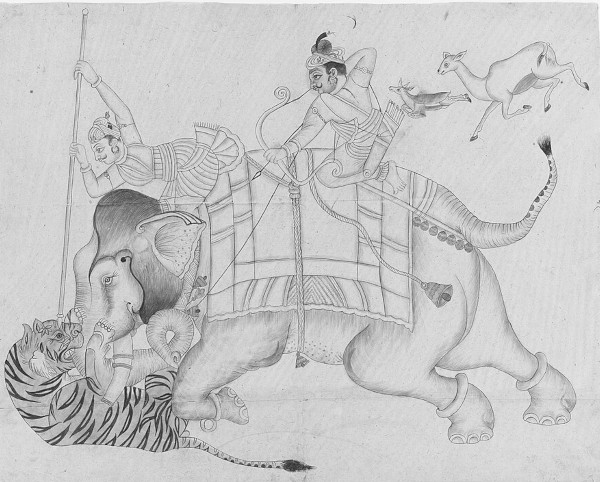

At the coronation of an ancient Hindu Raja he was sprinkled with the water of holy rivers mixed with the essence of holy plants, and he stepped on a tiger skin. In the past, when tigers met royals there was no hiding, there was death – the tigers death, eventually. An ancient custom required combat with a tiger to establish claim to kingship.

The Gupta tiger hunts

In the fourth century, Emperor Samudragupta fought a tiger, a coin thus titled him ‘the conqueror of tigers’ (with the legend vyaghraparakramah).

This Tiger-slayer type Dinar from Kumaragupta I, 409 – 450/452 BC. shows, the kings power. He is standing, shooting a bow and killing the tiger which falls backwards; his right foot even tramples on the predator.

Beside the Tiger slayer type coins of Samudragupta there exist also Lion Slayer (simhavikramah) type dinars of Chandragupta II.

The animal-slayer motif was popular in the art traditions of the Sumerians (4100 to 1750 BC) , Hittites (1650 to 1200 BC), Greeks (1200 to 323 BC), Persians (550 to 330 BC) and others. Mostly the lion, and to a certain extent the tiger is present where this beasts did roam.

This motif, prevalent across various cultures and time periods, symbolizes power, control, and sometimes, the taming of wild nature. A vast diversity of animals are depict in fighting scenes, like wolves, bulls and bears or even dragons.

The Mughal tiger hunts

Divyabhanusinh explains in, Lions, Cheetahs, and Others in the Mughal Landscape:

Tigers are rather sparsely noticed in Mughal records. This is not surprising at all.

The animal’s preference for thick cover, its solitary nature, its nocturnal habits, and its absence from grasslands and scrub jungles made it very elusive.

The tiger was not likely to be met with frequently in the path of imperial peregrinations.

The lion was royal game, tiger was not; it was an object of shikar (hunting expeditions) when met.

Tiger or Lion?

The word for the feline in the Jahangir’s text is sher babr, Persian for tiger; the word for the lion in Persian is shir.

باگهہ बाघ bāgh, = H باگها बाघा bāghā, [S. व्याघ्रः Prk. वक्वो, वग्घो], s.m. Tiger (syn. sher); lion.

باگها बाघा bāghā, = باگهہ बाघ bāgh, [S. व्याघ्रः Prk. वक्वो, वग्घो], s.m. Tiger (syn. sher); lion.

P ببر babar [Zend bawri; S. babhru], s.m. Lion; tiger (syn. Sher-babar).

Translators have confused the tiger with the lion as happens very so often in India today, where in Urdu/Hindi sher is usually translated as tiger and babr sher as lion.

As “Babbar” did not carry through, the word “Sher”, a colloquialism, came into spoken Hindi (not proper Hindi) as well as into Punjabi and is used for both animals today.

The proper Hindi word for tiger is “Baagh” बाघ, the word for Lion is “Singh” or “Simha” सिंह.

The Rajput tiger hunts – shikars

By the tenth century, India’s Rajput kings (warrior-nobles) had become famed for their shikars (hunting) prowess. Their courts relished game meat, and hunting partridge, rabbit, antelope, and deer was both a tradition and a statement of power.

In Central India, the Maharajas of Rewa believed it was auspicious to kill 109 tigers before ascending the throne or going to war.

Rewa Maharaja Martand Singh shot 131 tigers in his lifetime. On one such shikar in the adjoining jungles of Bandhavgarh in 1951, the Maharaja came across a tigress with four cubs, of which one cub was white.

The tigress and her three other cubs were shot down, but the white tiger cub was captured and brought back to the palace.

The Maharaja named this cub, Mohan (“charming” or “enchanting”, also one of the many forms of Lord Krishna) and started a captive breeding program.

The captive white tigers seen across the world today, are believed to be Mohan’s progeny.

The British Raj

Big game hunts became a favorite pastime for the British Raj that succeeded the Mughals.

The imperialists, were keenly aware that as royal beasts and masters of the jungle, Tigers had been closely associated with Indian rulers.

British rulers of the Indian subcontinent appropriated the idea of the tiger hunt as a demonstration of masculinity, power and ability to lead.

For the employees of British East Indian company and their representatives, tigers also represented all that was wild and untamed in the Indian natural world. Therefore, by killing tigers the colonial power was also symbolically staging the defeat of Tipu Sultan and other Indian rulers who dared to get in the way of Britain’s imperial conquest of India.

Tipu Sultan, the Tiger of Mysore

The tiger or tipu, Tipu Sultan, was known as the ‘Tiger of Mysore’. From 1782 on, he was one of India’s most powerful princes. Tipu identified himself with the tiger.

Bubris (stylized tiger stripes) adorned the uniform of his infantry and palace guards, tigers crawled over sword hilts and crouched on the muzzles of his cannons while his ordnance bore a calligraphic representation of a tiger’s face reading: ‘The lion of God is Conqueror’.

Susie Green, the author of Tiger. 2006. writes:

“Tipu had nothing but contempt for the British. The walls of his capital were decorated with life-size caricatures of trembling white men being seized by tigers, but his pièce de resistance was a lifesize wooden organ in the form of a tiger devouring a British redcoat who emits pathetic groans while the tiger makes ‘the growling cough of the Bengal tiger as it kills’.”

This was said to represent the fate of the son of an old adversary of Tipu’s, General Sir Hector Munro, who was carried off by a tiger during a hunting spree in the Bengal Sundarbans.

The British acknowledged Tipu’s tigerish nationalism by celebrating one of their victories over him by striking a medal depicting the British lion defeating the tiger of India. After Tipu’s defeat and death while fighting the Raj, the tiger organ was taken to London.

This limerick uses playful and absurd perspective to paint a vivid picture of a dangerous encounter between a woman and a tiger.

There once was a lady from Riga

Rode smilig away on a tiger.

They returned from the ride

With the lady inside

And the smile on the face of the tiger.

William S. Baring-Gould, The Lure of the Limerick (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1967). Sometimes attributed to Cosmo Monkhouse, on slim grounds. Riga is a port-city in Latvia. (Thomas Nast drawing for Harpers Weekly. Detail. CC-BY-4.0, edited.)

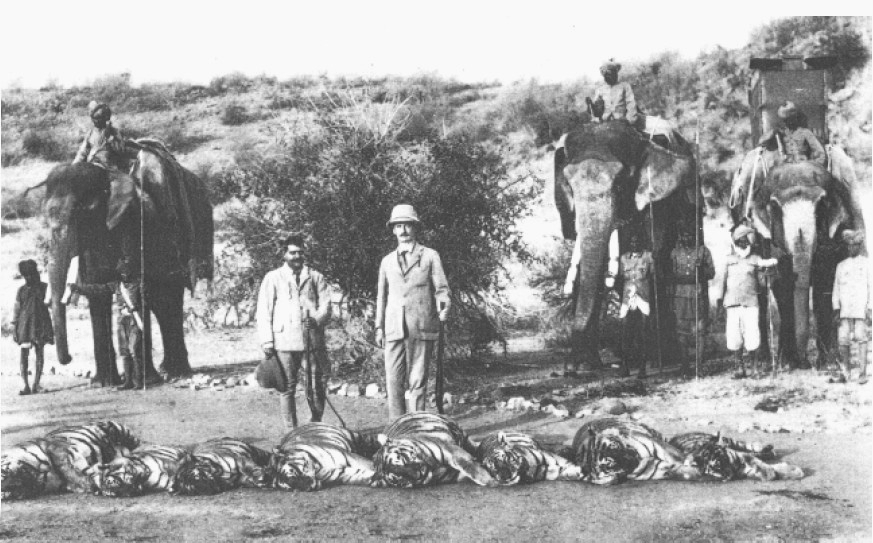

The carnage of wildlife from the 19th to mid 20th century India

The nineteenth and twentieth centuries reveal that the tiger population suffered unprecedented decimation when the proliferation of firearms and cars facilitated hunting for sport or medicinal purposes. People also hunted the tiger’s prey, leaving tigers with less and less to eat.

Tiger hunts intensified with the arrival of the British in 1757. Under the British Raj, tiger hunting became a theater of dominance, designed to flaunt imperial wealth and might.

Tigers were hunted nearly to extinction by Indian, Nepali (princes and maharajas), and British nobles, bureaucrats and army officers working for the East Indian company.

In the 1850s, Colonel Geoffrey Nightingale, commander of the 3rd Cavalry in Hyderabad, reportedly killed 300 tigers.

In his book ‘Tiger – Portrait of A Predator’, Valmik Thapar mentioned: ‘

‘The highest known individual score is the 1,100 tigers shot by the Maharajah of Surguja.”

In the book, ‘Under the Shadow of Man-Eaters’ by Jerry A. Jaleel, recorded:

When King George V ascended the throne, he marked the occasion with an extravagant hunting expedition to Nepal. In just ten days, he and his party slaughtered 39 Royal Bengal tigers, 18 Greater One-Horned Rhinos, and a Sloth Bear in what is now Chitwan National Park.

Colonel Geoffrey Nightingale had shot more than 300 tigers in India. William Rice had shot 158 tigers, including 31 cubs between 1850 and 1854 in Rajasthan. One civil Judge bagged over 400 tigers in the short period of his service in Bengal. Simpson had killed no less than 600 tigers during his 21 year stay in India.

Percy Wyndham had bagged no less than 500 tigers during his service in India.

Captain Forsyth had shot 21 tigers in one month.

Gordon Cumming had shot 73 Tigers in the year 1863 and 10 tigers within a span of five days in the following year.

Nrupendra Narayan of Bihar had killed 370 Tigers, 208 Rhinos, and 430 buffaloes between 1871 and 1907.

The Indian heads of various states and provinces- known as ‘rajas’ and ‘maharajas’ were no less guilty in this regard as they also indulged freely in unscrupulous slaughter of the then abundant yet precious wildlife.

The 1920s brought even more extravagance. Umed Singh II, Maharaja of Kota, Rajasthan, roamed the forests in a flaming-red Rolls-Royce Phantom, custom-fitted with a machine gun and a Lantaka cannon — a vehicle designed solely to exterminate wildlife.

The Maharaja of Nepal had shot 433 Tigers and 53 Rhinos between 1933 and 1940.

Newly crowned Rewa Kings in Central India thought it auspicious to slay 109 tigers after their coronation. Shooting a tiger was a coming-of-age ritual for young Indian princes.

Maharaja’s of Udaipur, Vijayanagar, and Bikaner shot dozens, sometimes hundreds of tigers each and decorated their palaces with tiger pelts and tiger heads and posed in front of piles of dead Tigers.

According to historian Mahesh Rangarajan, “In the fifty years between 1875 and 1925, 80.000 tigers, 150.000 leopards and 200.000 wolves were killed in India. Probably an equal number were injured and died later of their wounds.”

All over Asia, humankind encroached upon the tiger’s natural habitats, converting them to agricultural lands.

In 1924, the tiger population in Asia was estimated to be more than 100.000.

However, in this century alone, three sub-species of the tiger were driven into extinction – The Bali, Javan and Caspian. Within less than a hundred years, in India it had declined to fewer than 3.200.

Yet in spite of this carnage, possibly as many as between 25.000 and 30.000 tigers survived in India.

The rule of tooth and claw: The man-eating Tiger problem in late colonial India

By encouraging the expansion of agriculture into uncultivated landscapes in order to improve revenue, the British intensified contact between humans and dangerous predators, and the man-eater problem was created and actually magnified in late colonial India.

The man-eating problem is man-created, and should therefore be man-solved.

The Raj attempted to extirpate the man-eater problem by offering generous rewards for the skins of leopards and tigers to bounty hunters.

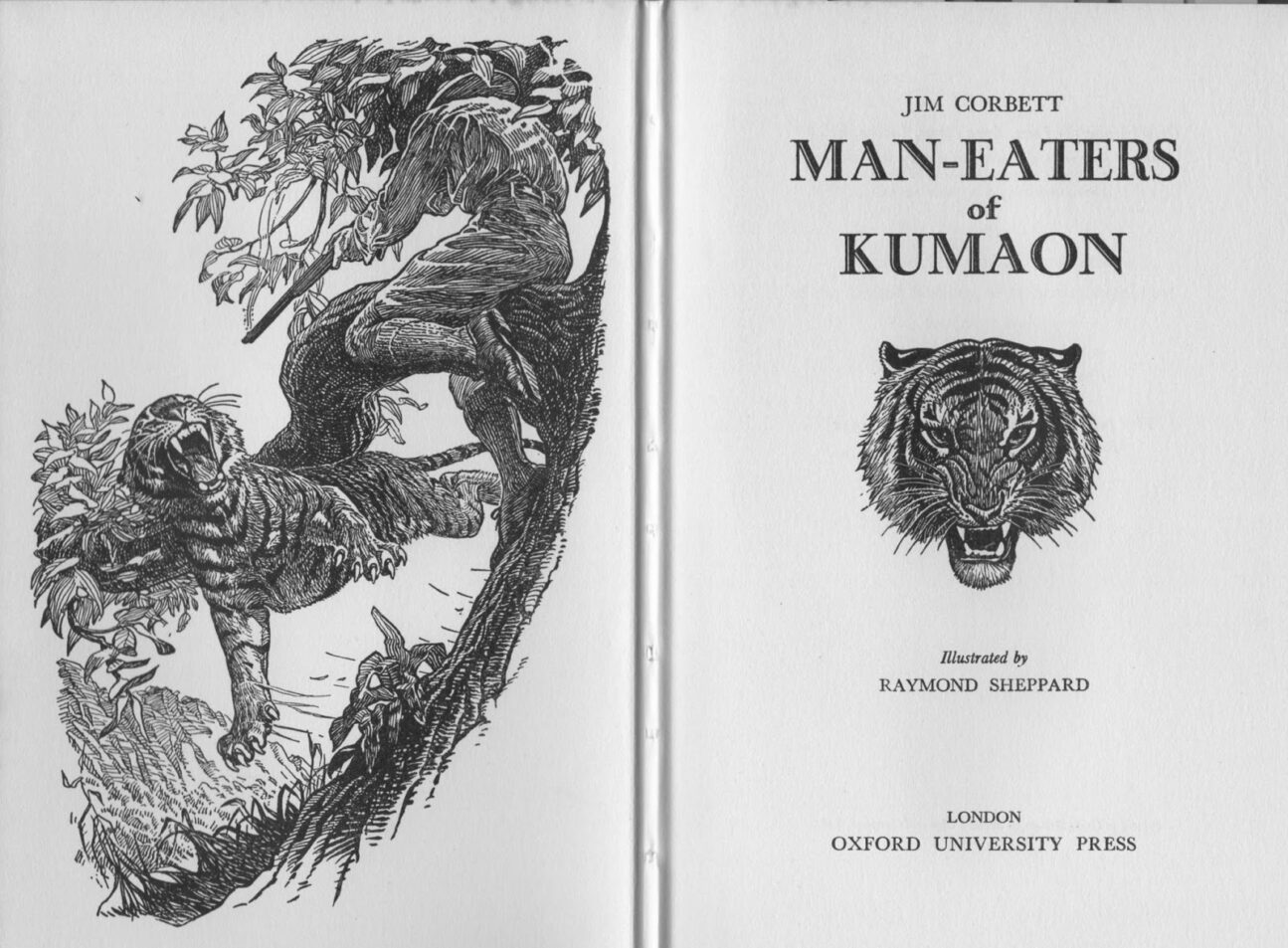

Jim Corbett

Man-eating adventures were made famous by sportsman Jim Corbett, who first organized big game hunts and, later made a living hunting “man-eating” tigers and leopards.

He wrote about such events from 1900s to the early thirties. As noted by Corbett in his book – The Man-Eaters of Kumaon,

“A man-eating Tiger is a tiger that has been compelled, through stress of circumstances beyond its control, to adopt a diet alien to it.

The stress of circumstances is, in nine cases out of ten, wounds, and in tenth case old age – human beings are not the natural prey of tigers, and it is only when tigers have been incapacitated through wounds or old age that, in order to live, they are compelled to take to a diet of human flesh.”

Scholars have shown that this is only partially true, some biologists have pointed out that man-eating occurs with transient tigers without a territory, when a cat’s natural food source is missing, and eventually they get hungry enough that anything and anyone is food.

The F. No. 15-13/2007-NTCA National Tiger Conservation Authority (Statutory Body under the Ministry of Environment & Forests, Govt. of India) states in the Guidelines for declaring big cats as maneaters:

“If a tiger/panther begins to seek out, stalk and wait for human beings and has after killing a person, eaten the dead body, it is established beyond doubt that the animal has turned into a man-eater.

It is not necessary in such cases to wait till several human lives are lost. It may be difficult to establish such cases after the first case, but after the second case of human kill it can easily be decided if the animal has turned into a man-eater. […]

A male tiger killing a human being near a village or in sugarcane field will in all probability be a man-eater.”

The baghauts are the ghosts of men slain by tigers, for whom tiger shrines are erected on the spot of their sad end. Such memorials are found all over tiger reserves, sanctuaries and villages.

Factors that may cause human–tiger conflicts include tiger movements, fragmentation of corridors, and human disturbance.

Randeep Singh

The renaming in 1957 of the Ramganga tiger sanctuary as the Corbett National Park, in memory of one who dedicated his life to the service of the simple hill folks of Kumaon, is a good indication of the respect in which his memory is held, states M. Booth, in: Corbett, Edward James (1875-1955), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Honored as a friend to the people and the wildlife of India, Corbett is above all remembered as a great shikari.

The famous slayer of man-eating tigers and leopards whose unparalleled success between 1907 and 1946, is credited with killing at least 33 man-eaters in the hill districts of Kumaon.

Corbett’s hunting adventures coincided with widespread nationalist disturbance, Ghandi’s noncooperation movement and the advent of a local peasant campaign to reassert customary rights over forests that the Indian Government had appropriated.

This hunter turned conservationist was there to maintain the appearance of British authority, sovereignty and effective governance, at a time when the focus of power was actually moving towards the Indian National Congress.

“Fifteen hours on the hard branch had cramped every muscle in my body, and it was not until I had swarmed down the tree, staining my clothes in the great gouts of blood the tiger had left on it, and had massaged my stiff limbs, that I was able to follow him. He had gone but a short distance, and I found him lying dead at the foot of a rock in another pool of water.”

Raymond Sheppard’s illustration of “The Kanda Man-eater from “Maneaters of Kumaon”. Public domain,edited.

In colonial discourse, ‘recalcitrant wild animals’ such as man-eating tigers and leopards were readily equated with ‘disobedient human beings’ such as ‘thugs’ and Dacoits.

Corbett’s account of the part that he played in the campaign to capture the ‘criminal tribesman’ Sultana is seamlessly interwoven with his more conventional hunting adventures. The reader joins Corbett in the familiar process by which he ‘tracks’ and ‘stalked’ his quarry.

Later James (Jim) Corbett and Kenneth Anderson advocated for laws to establish reserves and sanctuaries for the tiger.

“The Tiger is a large-hearted gentleman with boundless courage and when he is exterminated – as exterminated he will be unless public opinion rallies to his support- India will be the poorer by having lost the finest of her fauna.”

Jim Corbett

Post- Independence big game hunting tourism

After Indian independence in 1947, a legal vacuum unleashed further devastation. With no hunting restrictions in place, a post-colonial tiger slaughter began.

Foreign and domestic hunters alike flooded into India. Tiger tourism – but with rifles – was now accessible to anyone with money or influence.

By 1965, the Maharaja of Surguja proudly told biologist George Schaller he had personally killed 1.150 tigers. The trophy-hunting era nearly wiped out India’s largest cats and removed the strongest specimens from the gene pool.

Project Tiger

A ban on tiger shooting was imposed in 1970, the Wildlife Protection Act was passed in 1972 and the Indian Board for Wildlife was set up in 1972.

The first-ever all-India tiger census was conducted in 1972 which revealed the existence of only 1.827 tigers. Project Tiger was launched in 1973 in nine reserve forests.

Project Tiger initially started as a task force set up within the Indian Board of Wildlife chaired by Dr Karan Singh, Minister for Health and Family Planning.

This project was launched in Jim Corbett National Park, Uttarakhand, under the leadership of Indira Gandhi.

“The tiger cannot be preserved in isolation. It is at the apex of a large and complex biotope.

Its habitat, threatened with human intrusion, commercial forestry, and cattle grazing, must first be made inviolate.”

Prime Minister, Smt. Indira Gandhi says.

The objectives of the Project Tiger were clear – saving Royal Bengal Tigers from getting extinct.

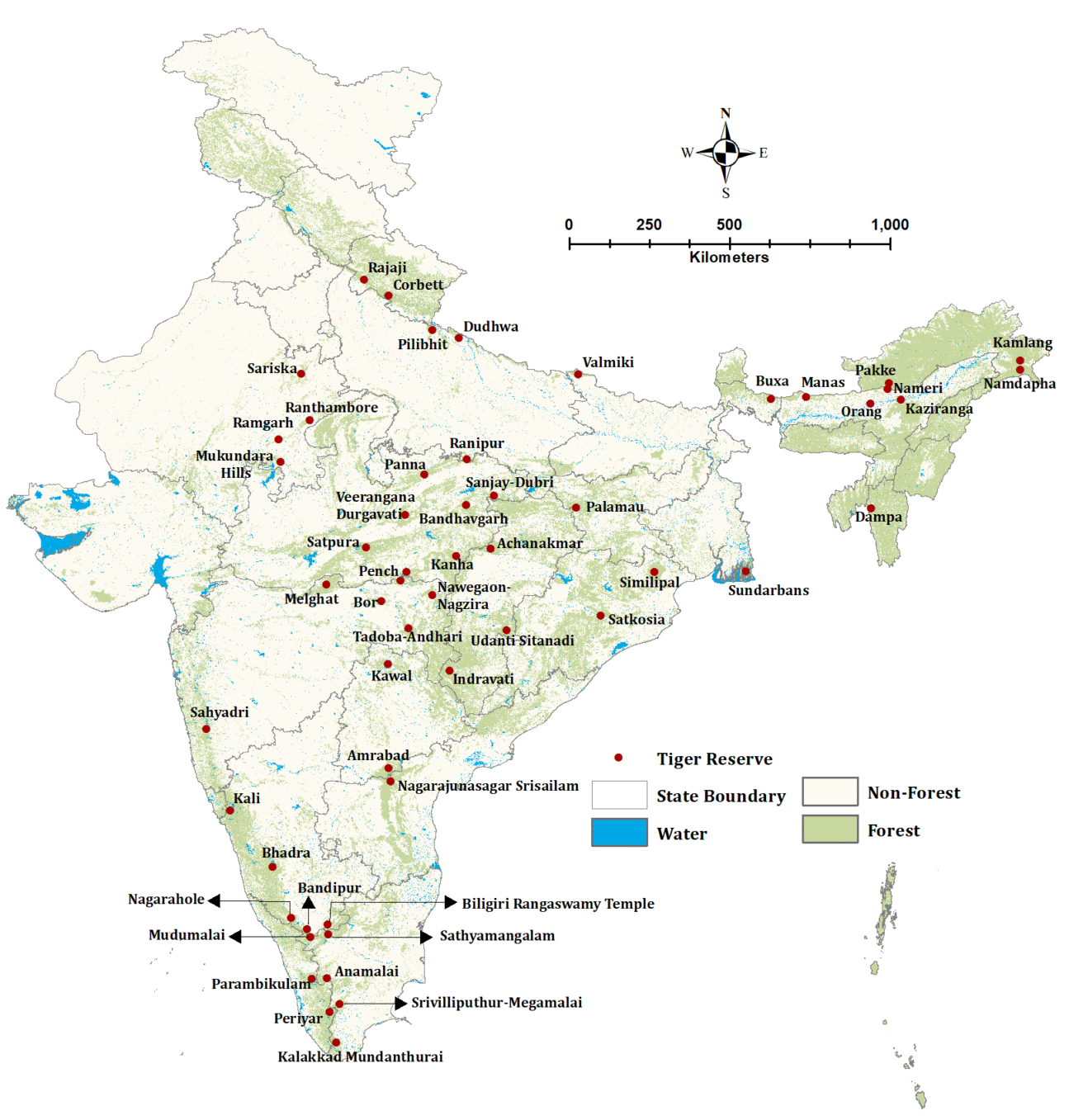

Map showing locations of Tiger Reserves in India

Initially, nine tiger reserves were established across different regions of India:

- Corbett (Uttarakhand); Palamau (Jharkhand); Simlipal (Odisha);

- Sundarbans (West Bengal); Manas (Assam); Ranthambore (Rajasthan);

- Kanha (Madhya Pradesh); Melghat (Maharashtra); Bandipur (Karnataka).

So far, 58 tiger reserves have been established in the country:

Tigers are adapted to wide range of environments, they are found in all ranges of forests, from the Himalayan region in the north,at altitudes higher than 3000 meters, to tropical Western Ghats in the south and Mangrove forests of the Sundarbans.

Understanding tiger conservation in multi- use landscapes

India is home to approximately 3.700 tigers, accounting for 75% of the world’s wild tiger population.

This demonstrates that even in the world’s most populous country, it is possible to protect large carnivores. India’s tiger conservation strategy combines two approaches: some areas are strictly protected reserves (core area) , while others are multi-use landscapes (buffer zones) where tigers and local communities share space.

“nirvano vadhyate vyaghro nirvyaghram, chidyate vanam; tasmadvyaghro vanam raksedvanam vyaghram ca palayet.”

The Mahabharata

The Tiger dies without the forest, and similarly the forest is cut down without the Tiger.

There can be no forest without Tigers and no Tigers without a forest.

The forest shelters the Tigers and Tigers guard the forest.

Today sanctuaries and parks are being squeezed by an encroaching, teeming sea of humanity. Tiger reserves are bordered by a patchwork of rice paddies, crop fields, hemmed in by villages, cities, and all sorts of development.

The surrounding land is segmented by roads, railways, scarred by massive mines and other barriers that render it dangerous and virtually impassable for these wide-ranging predators. Genetic isolation has led to inbreeding, threatening the long-term health and resilience of the tiger population.

According to Ninad Avinash Mungi, human population density alone is not what determines whether tigers can thrive—it’s people’s lifestyles, economic conditions, and cultural attitudes that shape their willingness to share space with large carnivores.

Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book portrays Sher Khan as a blood thirsty, revengeful and ferocious beast who is after Mowgli. Although the idea of having tigers nearby might seem alarming, attacks on humans are rare.

Human-Wildlife Conflict is defined as

‘interaction between humans and wildlife where negative consequences, whether perceived or real, exits for one or both the parties when action of one has an adverse effect on the other party.’

“If a person is killed by a tiger, the family receives financial compensation from the government”, explains Ninad Mungi. Also for farmers losing cattle to a tiger financial compensation is given.

Tigers, being at the apex of the food chain, are indicators of the stability of the ecosystem.

Habitat loss and poaching are important threats to species survival. Poachers kill tigers not only for their pelts, but also for components to make various traditional East Asian medicines. Other factors contributing to their loss are urbanization, habitat fragmentation and revenge killing.

India is the only place in the world where cats eat dogs.

Large felid species (leopard, tigers, lions) hunt dogs in India, Bengal and Nepal, too. As for the Guidelines for declaring big cats as maneaters:

A male tiger killing a human being near a village or in sugarcane field will in all probability be a man-eater.

This evidence should not be used against panthers, which usually live close to villages and move in the night even though the village in search of dogs, unless the panther has begun to lie in wait for human beings.

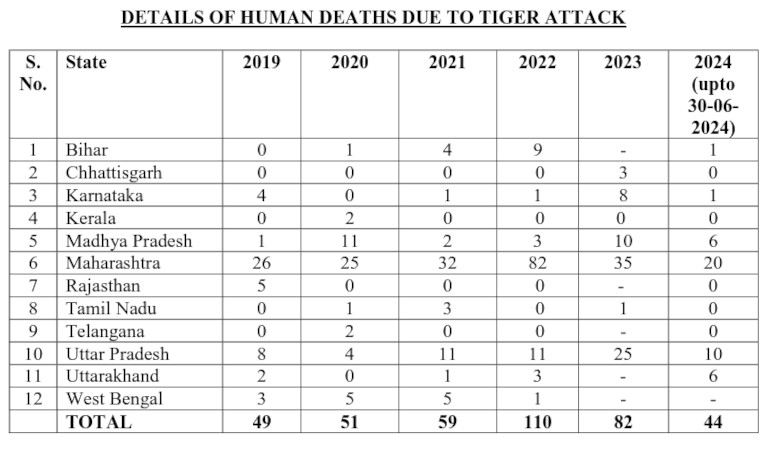

Details of human deaths due to tiger attack and tiger deaths reported by States due to poaching, seizure and unnatural causes

* Data for 2024 only up to 30 June 2024

Unlike tigers, elephants interact more with human settlements or agricultural areas, increasing the likelihood of conflicts. This can be in search of food, or due to migration and habitat fragmentation. Elephant attacks claimed 6015 human lives in the twelve years between 2012-13 and 2023-24.

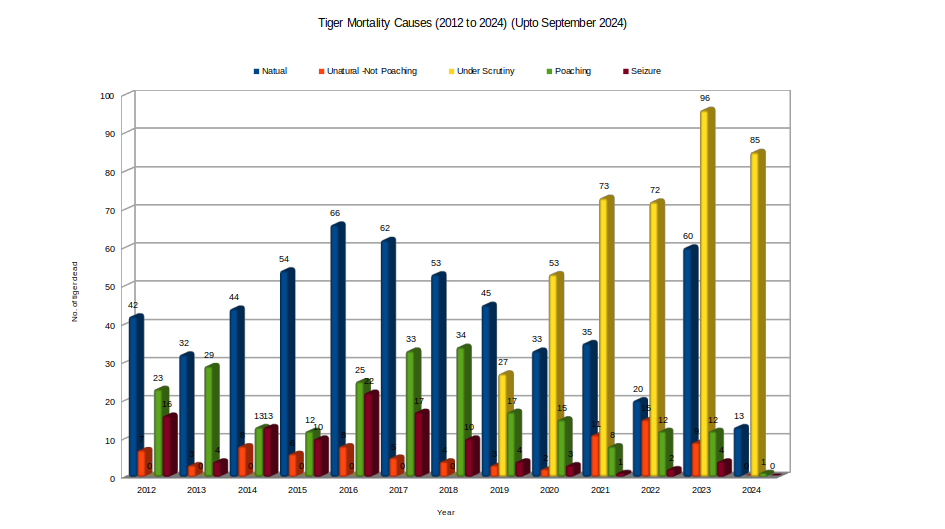

How unnatural tiger mortality looked like in India (January 2011 to September, 2016):

Poaching: Poaching accounted for 52 (66.7%) of mortalities under unnatural causes. Among the

poaching cases, 30 (57.7%) were attributed to poisoning, 12 (23.1%) to electrocution, six (11.5%)

due to injuries from snaring or trapping, and in two (3.8%) instances each, the animals were

directly beaten to death and shot dead following confrontation.

Accidents: Accidents accounted for a total of 18 (23.1%) mortality events of which eight were from

vehicular collision, four due to train collision, four due to unintentional fire, one each from drowning

in open well and injuries sustained due to falling of tree trunk.

Legal elimination: Among reported cases, eight (10.3%) tigers were shot dead as part conflict

mitigation strategy over the study period

The Bengal Tiger in India’s history and lore

Ancient evidence of tigers in India

The presence of Neolithic/Chalcolithic cave paintings of tigers in Bhimbetka rock shelters of central India (30,000–100,000 BP) suggest, the striped carnivore to be early entrants into India.

The scenes reflected in these paintings usually depict hunting and dancing humans, and fighting animals like antelopes, bisons, lions and tiger.

The tale of the Harappan tigers

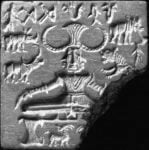

Shibani Bose tells us in his latest work Mega Mammals in Ancient India: Rhinos, Tigers and Elephants, the tiger is found on 16 seals from about 5,000 years ago, from Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro.

Like the Harappan horned deity, surrounded by Rhinos and tigers, described by scholars as the Vedic Pashupati , or lord of the beasts.

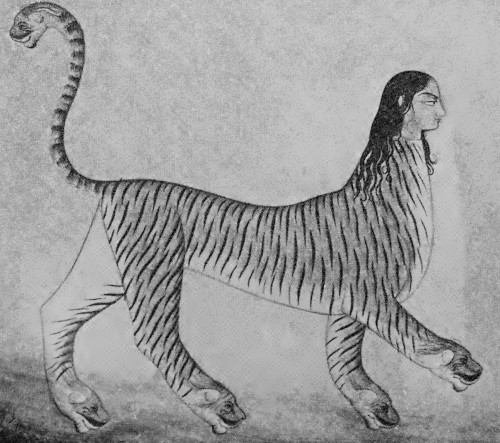

A half woman and half tiger seal, of which the front half is a woman and the hind half a tiger has also been unearthed.

This undated 19th century painting of the legendary Indian chimera, shows her paws and tail capped with ravening heads.The Chimera was a monstrous fire-breathing female and male creature of Lycia in Asia Minor, composed of the parts of three animals.

It’s the oldest sphinx or Chimera image in the world, showing a woman fused with a tiger. We don’t know what it means. Tigers, including this tiger goddesses, are part of Harappan lore but her story is lost.

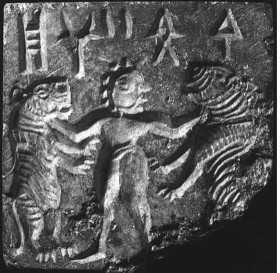

Asko Parpola writes: ” In Mesopotamian art, the fight with lions and / or bulls is the most popular motif…The six dots around the head of the Harappan hero are a significant detail, since they may correspond to the six locks of hair characteristic of the Mesopotamian hero, from Jemdet Nasr to Akkadian times,” (Deciphering the Indus Script, pp. 246-7).

The figure strangling the two tigers may represent a female, as a pronounced breast can be seen in profile. Earlier discoveries of this motif on seals from Mohenjo-daro definitely show a male figure, and most scholars have assumed some connection with the carved seals from Mesopotamia that illustrate episodes from the Gilgamesh epic.

The Mesopotamian epics show lions being strangled by a hero, whereas the Indus narratives render tigers being strangled by a figure, sometimes clearly males, sometimes ambiguous or possibly female.

This motif of a hero or heroine grappling with two wild animals could have been created independently for similar events that may have occurred in Mesopotamia as well as the Indus valley.”

Keeping in mind the varied representations of the predator, it was argued by scholars, that the tiger appears to have different roles in the Harappan world: as one of the wild beasts associated with the horned ‘deity’ and a woman fused with a tiger image and as the victim of a hero story. The tiger appears to mark different levels of Harappan narrative: myth, epic, and also perhaps legend-folktale.

However, despite the richness of the evidence available, and till the absence of a deciphered script, the elusive Harappan tiger will continue to elude us.

The faunal evidence testifying the presence of the tiger at early historic sites is limited. However, we have sites (Pakistan and Rajasthan) yielding evidence for the tradition of modelling the tiger in terracotta from mid-second century BC till about the end of the second century AC.

The vedic Tiger of myth

The striped carnivore, it seems, was unknown to the authors of the Ṛgveda, as it does not

mention the vyāghra, the word for the tiger. Romila Thapar points out that the Ṛgveda was, however, familiar with the siṃha or the lion, and this she suggests indicated that the original authors lived in the Indo-Iranian borderlands where lions were common.

The Atharvaveda describes the striped predator as the mightiest and most dreaded of all the beasts of prey.

The magnificence of the animal, for instance, is alluded to in the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa (V, 3, 5,3).

The Vedas contain prayers and spells to subdue tigers and protect people, cowherds and shepherds from the menace of tigers, besides invocations that extol gods by ascribing to them the power and the qualities of tigers.

The Atharva-Veda stresses the destructive character of the animal. The Tattriya Samhita refers to the danger of waking a sleeping tiger. The Brahmanas use the term ‘shardoola‘ for tiger. Valmiki in the epic, Ramayana picturesquely describes situations by drawing metaphors from the animal world:

Dashratha, hurt by the cruel words of Kaikeyi, who asked for banishment of Rama, is compared to a deer, distressed and trembling at the sight of a tigress.

In some hymns the domestic fires are compared to the tigers that guard the house.

Indian Myth and Legend is a comprehensive book written 1921 by Donald A. MacKenzie: According to Upanishadic belief the successive rebirths in the world are forms of punishment for sins committed, or a course of preparation for the highest state of existence.

In the Code of Manu it is laid down, for instance, that he who steals gold becomes a rat, he who steals uncooked food a hedgehog, he who steals honey a stinging insect; a murderer may become a tiger, or have to pass through successive states of existence as a camel, a dog, a pig, a goat, etc.

Indra and the creation of the tiger

It is said to have Soma’s beauty for when the latter flowed through Indra, he became a tiger. Even in ritual contexts, the allusion is primarily to the vigor of the animal. In the piling of the fire altar, ‘Agni is Rudra; just as a tiger stands in anger, so he also (stands)’ (Taittirīya Saṃhitā V.5,7,4;).

As part of the sautrāmaṇī sacrifice, in the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa, the hair of a wolf, tiger, and lion are put into cups of spirituous liquor from which libations are made. The three animals are said to have emerged from the body of Indra after he forcibly consumed Soma:

From his urine his vigor flowed, and became the wolf, the impetuous rush of wild beasts; from the contents of his intestines his fury flowed, and became the tiger, the king of wild beasts; from his blood his might flowed, and became the lion, the ruler of wild beasts.

THE SAUTRĀMAṆĪ Kanda XII, adhyaya 7, brahmana 1

The predator itself along with the lion qualifies as an offering to the mighty Indra (Taittirīya Saṃhitā V. 5, 21). On the other hand, once again described as the king, it also figures as an object of worship for the priest (Vājasaneyī Saṃhitā XXI).

The tiger in Vedic scripts and Puranas

Here, tiger hair is said to help secure courage and the mastery over wild beasts, while the hair of the lion helps secure might and the rule of wild beasts (Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa XII, 7, 2, 8)

In the woods, wild beasts including lions and tigers are said to go about man-eating (Atharvaveda XII. 1, 49) and attacking cattle (Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa XI, 8, 4, 1). Thus, besides being a threat to human life, the animal is clearly an adversary particularly for the keepers of cattle.

Spiritually, tigers are considered advanced beings. Some of them might have been humans in their past lives or may assume a human birth in their next lives.

For example, Manusmriti (12.59) declares that those who take pleasure in hurting others will be born as carnivorous animals such as tigers, whereas those who eat forbidden food become worms.

King Dīrghabāhu I transforms into a tiger

A king. He was well learned but vain and arrogant.

He used to abuse Brahmins. Upset by his abuse, some Brahmins gave him a Ṣāpa (curse of Brahmin) that he would become a tiger. Worried and remorseful, he begged them to tell him how long he had to live as a tiger. They told him,

“After becoming a tiger, you will pounce on a Brahmin to eat him. The Brahmin, terrified at the sight of you, will chant the name of Nārāyaṇa (one of the names of Lord Vishṇu). At that very instant, a hunter will kill you. When you hear the name of Nārāyaṇa, you will be released from our Ṣāpa.”

The king became a tiger and after a while, he attacked a Muni named Aruṇi. The scared Muni kept repeating “Nārāyaṇa, Nārāyaṇa, Nārāyaṇa” and tried to run away. A hunter saw and killed the tiger. The king was relieved of the Ṣāpa. (Varāha Purāṇa – Surya N. Maruvada, in: Who is Who in Hindu Mythology. Vol. 1, 2020.)

Tiger in Buddhism

The tiger as an individual entity seldom figures in early Buddhist canonical literature. Though it is to be feared and stayed away from, when it comes to contexts describing might and splendour, it is the lion which is chosen as a point of reference, and irrefutably stands tall over all brute creatures.

The Buddha himself in an earlier incarnation sacrificed his life to feed a tigress so delirious with hunger that she was preparing to devour her cubs.

In doing so he demonstrated the greatest of Buddhist virtues, compassion.

Tigers and Lions feature in the ancient Buddhist texts of the Jatakas (∼2,400 BC) that depict Buddha as various animal incarnations, often as a noble lion. The tiger, thus, is dreaded yet admired. Its might is recognized, and more significantly is its crucial role as the protector of the forest.

Come back, O Tigers! to the wood again,

Vyaggha Jātaka (No. 272)

And let it not be leveled with the plain;

For, without you, the axe will lay it low;

You, without it, forever homeless go.

Tiger in Jainism

In the Jaina world, it seems that the tiger has a nearly negligible presence in the philosophical discourses of the Jaina canon.

Perhaps the only meaningful allusion is encountered in the prohibition on the use by monks and nuns of plaids made of tiger’s fur (Ācārāṅga Sūtra; I: 158).

Also, monks and nuns on begging tours are told to avoid noxious creatures including the tiger (Ācārāṅga Sūtra; I: 100).

The sacred tiger in Hindu mythology and iconography

Durga दुर्गा

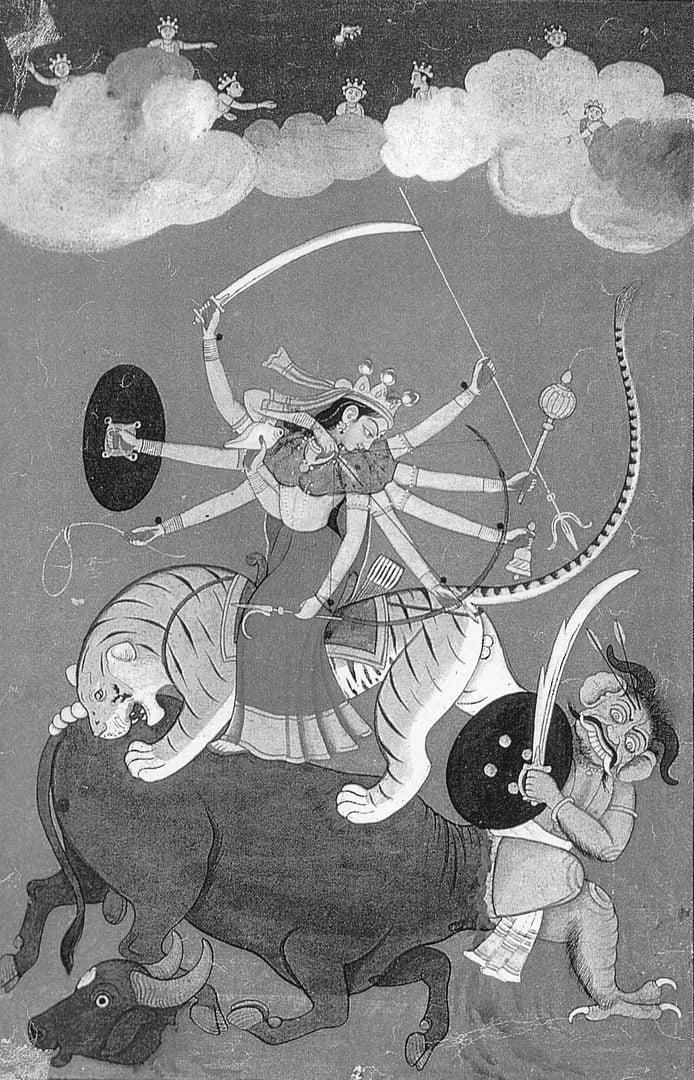

Durg दुर्ग is the Sanskrit word for “fortress, something difficult to defeat or pass” and means invincible and impassable. Maa Durga, in the Hindu pantheon is depicted as a goddess riding a tiger or lion .

Goddess Durga’s vahana (vehicle) is usually depicted as a great cat, but just what kind of cat is often unclear. Ancient texts call it a lion or a tiger, and sometimes a more imaginary creature. Such iconography indicates the fluid interrelation of a variety of goddess forms.

The great cat has the thick, striped body of a tiger; the tufted tail, short mane, face shape, and color of an Asiatic lion; and the facial “tear-lines” of a cheetah (now reintroduced in India and once used as a royal hunting animal).

The Great Goddess as Ishwari, with Bhadragaura, a rare form of the god Shiva. Rajasthan, 1700-1725.

Public domain,edited.

Goddess Durga was born from the combined powers of Lord Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva and is worshiped as a mighty warrior who fights the demon Mahishasur. Her devotees see her as a protector deity.

As Mahishasura-mardini is sitting on a tiger and slaying the half-buffalo demon Mahishasura. In Nepal also, her battle with Mahisha takes place on the back of the tiger.

While Durga is the destroyer of evil, her tiger mount represents power and immortality.

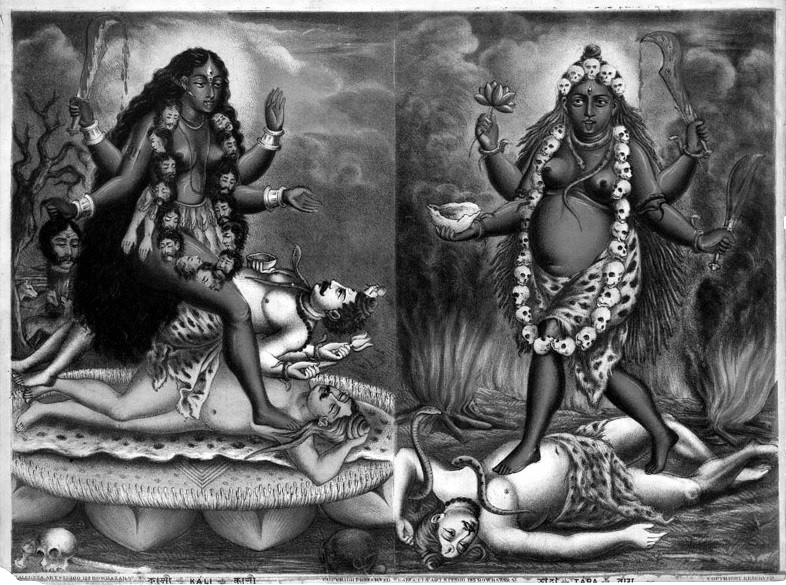

Durgas more ferocious forms as Tara, Kali and Shakti, ride a tiger or are covered with a tiger/leopard skin.

Kali (left) and Tara (right) have similar iconography, both are adorned with a garland of severed heads or skulls, a tiger or leopard skin skirt, and a lolling tongue.

In the Shaivism and Shaktism tradition of Hinduism, goddess Tara तारा is considered a form of Adishakti, the tantric manifestation of Parvati.

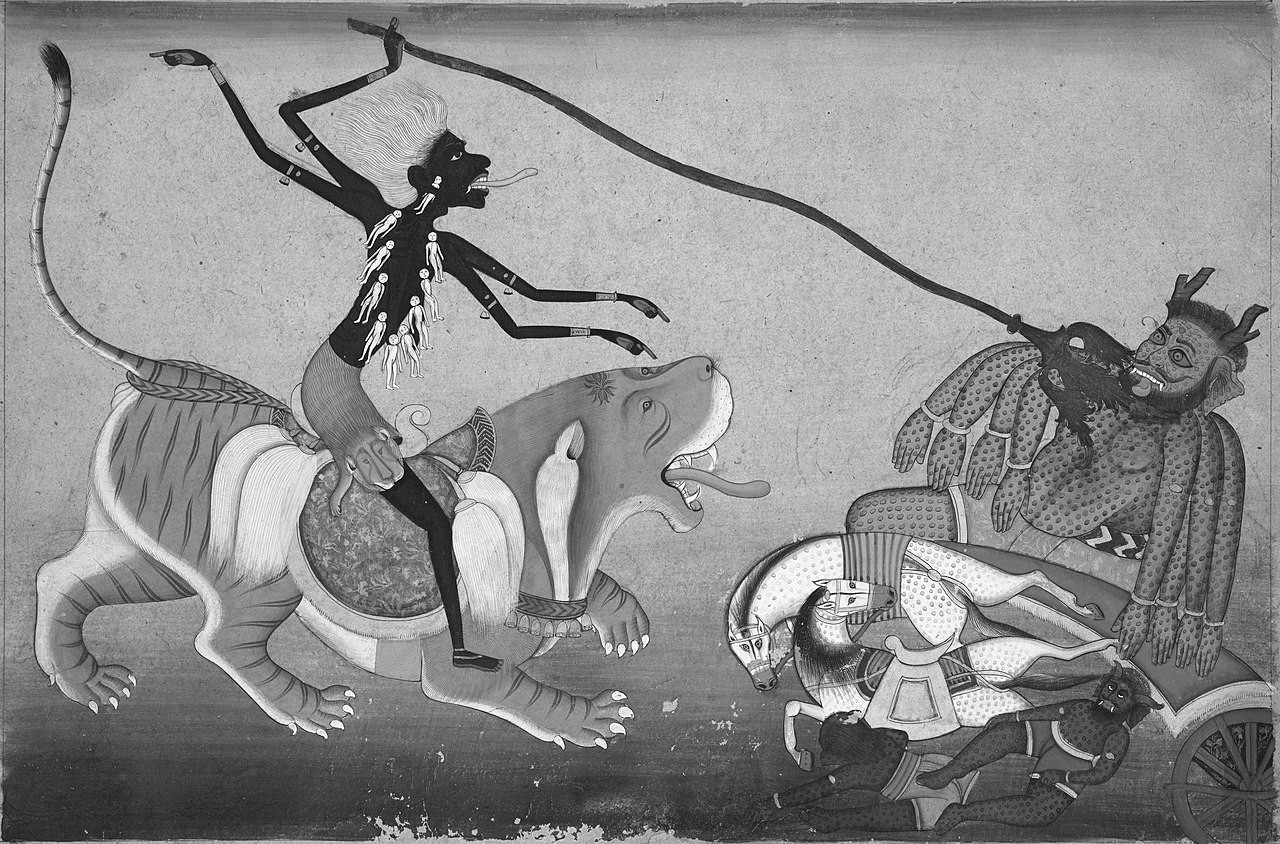

Kali rides a tiger

The four-armed, black-skinned Kali is a Hindu goddess who is the destroyer of evil, and the Mother of the Universe, she rides a jakal and sometimes a tiger. She is wearing a lion skin.

In the picture, Kali has already slayed two minor demons and the horses pulling the chariot of a large, green demon. Demon blood could generate another demon if it struck the ground. Kali extends her tongue to ensure that no demon blood can strike the earth.

The demon is a metaphor for wicked thoughts that give rise to more evil thoughts; Kali aids her followers in eradicating them all.

Tiger dance

Tiger Dance is performed during Dussehra in honor of goddess Durga. Mimicking the tiger, or the tiger dance, is very popular in several parts of India. It is called Puliyattam in Tamil, Puli vesham in Andhra Pradesh, Puli kali in Kerala, Bagh nritya in Orissa and Huli kunita/Huli vesha in Karnataka.

Young men paint their bodies yellow with black stripes to resemble tigers. They pretend to catch deer, or flee from a hunter or may even convey the motions of being hunted and killed. The dance and movements are accompanied by the loud beating of drums.

Puli kali celebrates the annual return of the dethroned king of Kerala, Mahabali, in the form of the harvest during Onam (annual harvest and Hindu cultural festival). The dance owes its origin to the Muslims who originally introduced it during Muharram, the recollection of the murder and martyrdom of Ali, Prophet Mohammed’s son-in-law, who was a great warrior and thought to have possessed the strength of a tiger.

The Tamil Konars and Chettiars communities organize tiger dances during the Pongal (harvest) festival, puli atam mimicking a tiger moving on its hind legs to the rhythm of the drums.

There is a strong influence of kalaripayattu, the martial art of Kerala with painted bodies and faces recreating the feared predator.

All along the coastline regions in the Southern parts of India, there is also a tradition of tiger dance, to celebrate the birth of Lord Krishna on Janmashtami. On this day, men of all ages paint themselves with black stripes over a yellow base, wear tiger masks and dance in the streets.

Mahadevi महादेवी riding a tiger: The tiger in the Indian culture of Shaktaism

Durga appears in Hindu mythology in numerous forms and names, but ultimately all these are different aspects and manifestations of Mahadevi, the goddess.

As Shakti, she is worshiped by Shaktas, and in this aspect, she denotes the mother of all creation, including the gods.

Within the Shâkta tradition, the distinction between Parvati and Durga is generally understood, with Parvati as the wife of Shiva and Durga as a separate, powerful form of the Goddess.

Hindus worship Shakti शक्ति (“power” or “energy”) as Devi, the divine mother. Durga, in her various manifestations is venerated as Mahadevi, the Great Goddess. In this form, she represents the nurturing mother, the fierce warrior, and the cosmic force of creation and destruction.

Sapta Matrikas मातृका

The Sapta Matrikas, the seven mothers of Tantric religion are seen as mother goddesses. Some matrikas are depict as half animal-half woman, like Narasiṁhi/ Simhasya (the lion-faced goddess), Vagalamukhi (the bird-faced goddess), Vinayaki (the elephant faced goddess), and Varahi (the boar-faced goddess). Matrikas are goddesses of the battlefield, numbering seven, eight or ten.

Narasimhi (प्रत्यङ्गिरा Pratyangira, Atharvana Bhadrakali, Simhamukhi) is an incarnation of Mother Goddess that is associated with the Narasimha avatar of Hindu God Vishnu. Devi has a lion-face and rides a tiger.

Varahi वाराही is called Barahi in Nepal. In Rajasthan and Gujarat, the Devi is venerated as Dandini. This incarnation of Mother Goddess is associated with the Varaha avatar of Hindu God Vishnu. She has a sow-face and rides a tiger.

Chamunda चामुण्डा, this mother has a very thin body and a frightening face with grin. Devi also wears a garland of the skulls, a tiger skin is her garment and her abode is under a fig tree.

Rudra रुद्र

Rudra (1000 BC) is the Vedic deity of the wind or storms, medicine, and the hunt.

The Pashupati seal, showing a seated and possibly tricephalic (3 horned) figure, surrounded by a tiger,a rhino, an elephant, a goat, a bull; circa 1400-1900 BC- also known as “Lord of the Beasts” or Rudra. (The Pashupati seal Mold of seal with Rhino. CC-0., edited.)

Depending upon the period, the name Rudra can be interpreted as ‘the most severe roarer/howler’ or ‘the most frightening one’. The Yajur Veda describes Rudra as clothed in a tiger skin. This prompted sages and yogis to sit on tiger skin while meditating.

Rudra is linked to Agni, the fire god, and Vayu, the wind god, reflecting his elemental nature. The deity is also identified with Shiva.

Shiva शिव

Lord Shiva is often depicted wearing or seated on a tiger or leopard skin. A tiger skin, Vyaghra Charm व्याघ्रचर्म, (Vyāghra व्याघ्र, tiger) a symbol of invincible strength, therefore, he is also known as Vaghambardhari.

Holy sages sit on a tiger skin while in deep meditation in forests or in caves, as no insect, snake or

scorpion will go near it due to fear, so the belief.

Shiva Purana, on the creation of the Tiger:

The Brahmins were now furious, and desired a as a summary vengeance. They held that a Brahmajnani mysteries of Brahma), was superior to any tricky fiend whatever.

They performed new incantations and sacrifices, and produced a tiger as initiate in the whose mouth was like a cavern, and his voice like thunder amongst the mountains.

This they sent He seized the tiger and squeezed against the god S’iva. it to death, and he still wears its skin as a Kummerbund. (Lillie Arthur. India in Primitive Christianity. 1909.)

Shiva also bears the name Vyaghranatheshvara (Lord of the tiger), because he once had slain a demon who had taken the form of a tiger.

Shiva takes the form of a tiger

The Baghnath temple in Uttarakhand, from the 14th-century is dedicated to Lord Shiva and stands at the confluence of the Saryu and Gomti rivers.

The name “Bagnath” literally translates to “Tiger Lord.”

According to Hindu mythology, Sage Markandeya, known for his immortality, performed penance at this very spot to appease Lord Shiva.

Pleased by his devotion, Lord Shiva manifested himself in the form of a tiger (Bagh). Mother Parvati took the form of a cow.

Markandeya seeing this ran to protect the cow and chase away the tiger. When the sage got up from there Sarayu found her way and started flowing downwards. When Shiva and Parvati heard the sound of flow of Sarayu they came back to their original forms. Then Markandeya praised Shiva and said

“Your name is Vyaghreshwar.”

After this, Lord Shiva and Mother Parvati came in their real form and appeared to sage Markandeya and sage Vashishtha and blessed them.

After this the confluence of Saryu River and Gomti River took place. This local legend forms the basis for the temple’s name and highlights the significance of the location for Shiva devotees.

When gods came they said that as Shiva had been praised here this place would be called Bageshvar.

(Pande Badri Datt. History of Kumaun. English version of Kumaun KaItihas. 1993.)

Vyāghrēṣwara

Once upon a time, an Asura named Dundubhi was killing and eating devotees who came to the Viṣvēswara (Lord Ṣiva) Temple in the city of Kāṣi (Varanasi). Ṣiva took the form of a Vyāghra (tiger) and killed the Asura to protect the devotees. Ṣiva thereby came to be known as Vyāghrēṣwara. (Vishṇu Purāṇa as in Maruvada Surya N. Who is Who in Hindu Mythology. Vol. 2 – 2020.)

Ayappa अय्यप्पा ಅಯ್ಯಪ್ಪ ஐயப்பன்

Lord Ayyappan of Sabrimali in Kerala is said on the one hand to be the son of Shiva and Mohin, Vishnu’s female form. He is also said to be an incarnation of the Buddha. He is usually depicted as a youthful man riding or near a Bengal tiger and holding a bow and arrow.

According to the myth, God transformed himself into a newborn, who was found by king Pandalam, who was childless.

Ayyappan was then adopted as the kings heir. After a short time, Pandalam’s queen produced her own son, and she tried to get rid of Ayyappan, asking him to procure tiger’s milk, the only thing that would could cure her illness.

Ayyappan went off to the forest and returned riding a tigress. In his search for tiger’s milk, Ayyappan had been sent to heaven by Lord Shiva to kill a demoness, Mahishi.

Ayyappan had succeeded in ejecting her from heaven and making her fall to Earth. The demoness asked him to take her as his wife, but, he, being celibate, decided not to accept her. However, Mahishi is given a prominent place at the Ayyappan shrine.

In recent years a winter pilgrimage has been instituted to the Ayyappan shrine, Sabarimala Sree Dharma Sastha Temple (between December 15 and January 15, depending on the lunar calendar).

Participants dress in black, take a vow of celibacy for the duration of the celebration, prepare for the pilgrimage by singing praises to Ayyappan, and then head off on the long trek. Women in their fertile years are

not permitted as Ayyappan is said to be “lord of celibacy.”

Tamil Nadu and Karnataka also house many Ayyappan temples. Ayyappan may bear a historical relationship to the deity Aiyanar of Tamil Nadu.

Ayyappan is sometimes also referred to as Shasta, or “ruler of the realm.” It is believed that Ayyappa is a form of Shasta.

According to Bhagavata Purana, Lord Shiva lay with Lord Vishnu while the latter was in the female Mohini form. Their carnal union resulted in the conception of the deity Shasta. Shasta is also known as Hariharaputra, the son of Hari (Vishnu) and Hara (Shiva).

The delicate coexistence: Tigers, people, and rural life in tiger habitats

Adivasis are the “first inhabitants” of India who mostly lived in remote, difficult to reach regions of the country.

Given that this tribes live in or close to forested areas, it is natural that the tiger features strongly in their folklore.

Where wild Tigers survive today, it is due to the numerous sacrifices made by the local communities, agreeing to relocate from their established homes in and around the various Tiger Reserves at the behest of the Indian Government.

Living with Tigers: Tiger worship among India’s tribal communities or adivasis

Tribal communities that share space with these large cats often view the felines, like tiger or leopards as “protectors”, “owners”, “family” or as “vehicles of the gods”.

Worship of the tiger god under different names is prevalent in many tribes of India.

The Gonds of central India, for example, believe that their ancestors’ spirits inhabit tigers, making the animal a sacred entity. Once a tiger kills a person, the person’s soul is believed to transform into a part of Waghoba, the tiger/leopard god. This belief fosters a sense of respect and reverence for the tiger, as it is seen as a vessel for the spirits of the deceased.

Tiger god, Waghoba, statues are often found at village entrances, as markers of attacks and also as symbols of respect for the kuladevta (clan deity) of the Gond community.

In some villages, these statues are built with the belief that Waghoba will protect them, reflecting a broader cultural narrative of coexistence and protection.

The Gonds carry the shoulder bone of the tiger in the belief that it will bring them strength.

Waghoba statues in agricultural fields, protect them against wild herbivores. This practice highlights the tiger’s dual role as both a revered deity and guardian of crops, underscoring the intertwined relationship between agricultural practices and wildlife in these regions.

Similar traditions exist across various parts of India and Southeast Asia, reflecting diverse yet parallel relationships between humans and tigers. In Arunachal Pradesh, the Nyishi and Mishmi tribes honor the tiger as a sacred animal, believing it to be kin. They perform rituals to appease the tiger spirit, especially during times of conflict.

Waghya is the god of the Warli tribe, represented as a shapeless stone. He is also the main deity of the Dhangers and Bapujipoa of the Kolis. This tribes believe, that the tiger will bring rainfall to the farmers in need and any insult to the tiger will result in a drought.

Similarly, in Chhattisgarh, the Baiga tribe worships Bagheshwar or Bagesur Dev and considers the tiger their spiritual brother and protector of the forest. They conduct elaborate ceremonies to seek the tiger’s blessings for their crops and safety.

In Goa, forest-dwelling communities worship Vyaghambar or Waghro, believed to guard villages and forests and prevent crop damage by keeping a check on wild herbivore populations.

The tigers of the Sunderbans are believed to be the owners of the forest and are worshiped as “Banobibi/Dakkhinrai” by both Hindus and Muslims.

Similarly, the Santhals and the Kisans of Orissa also believe the tiger to be the king of the jungle and worship it as Bagheshwar and Banjara.

Tigers have also been documented to play the role of a protector among Garo tribes of Meghalaya and Tulunadu tribe of South Kanara district of Karnataka. The Garos wear tiger claws in gold or silver as a necklace for protection.

The Irula tribe of Tamil Nadu also worship the tiger who is believed to offer protection from evil spirits.

Back to the past: from human- wildlife conflict to human-wildlife coexistence

Living with tigers has been an everyday reality for adivasi communities over centuries. Ancient tribal belief systems pre-date the onset of the human-wildlife conflict discourse by hundreds of years.

There have been many studies that explore the relevance of existing belief systems and narratives to conservation, specifically human-wildlife co-existence and discuss how animistic ideas contribute toward the sharing of space between local communities and big carnivores.

Local stories illustrate how; to deal with the losses caused by the tiger God eating their livestock or attacking humans, the people initiated a negotiation with the gods, ancestors, forest spirits etc. in animal form.

However, some adivasi narratives are particularly unique because they not only instill an ethic of not killing big cats (because they are family, brothers, ancestors, shape-shifter-shamans, spirits, forest entities…) they also provide ways in which to comprehend and process the loss and complexities that arise consequent to incidents of human-wildlife conflict (such as livestock depredation).

Local belief systems play a role in tolerance: missing cattle are seen as “prasad” – divine offerings – symbolizing a form of spiritual “taxation” for living amid predators.

The belief in the possibility of negotiating space with potentially dangerous or conflictual predators perhaps stems from feelings of relatedness and kinship.

Worship and festivals act as a manifestation of this bargain through offering animal sacrifice of livestock in exchange of his benevolence and protection from danger and harm.

When animals are perceived as persons or spiritual entities, rituals can play an important role in materializing their relationship with people.

Several scholars note that societies with such human-animal dynamics are built on values of mutual respect and reciprocity.

In such systems, humans and animals enter into obligations and failure to honor these can pose threats and complications.

This fragile harmony rests on a foundation of strict wildlife protection laws, timely compensation for livestock losses, and relatively low levels of conflict between humans and big cats, like leopards or tigers.

Integrating cultural practices with scientific approaches makes it possible to create a holistic strategy that respects traditions while ensuring safety for people and conserving wildlife.

Ashraf Shaikh

Tigers and leopards are no longer just seen as divine beings – they’re increasingly tied to economic interests.

And cultural shifts are slowly replacing reverence with pragmatism and animism with economics. The future of sustainable carnivore and forest conservation will depend on whether this carefully negotiated peace between human and beast can hold.

Sculptors and painters over the centuries have derived inspiration from the myths and legends associated with the tiger while poets, singers and dancers have written verses and songs and dramatized these stories.

The tiger is a major character in many traditional theater forms of different regions of the country-somewhere as a mighty divine form, somewhere as a comical figure to add humor to the traditional plays as in some stories of the Bhand Father of Kashmir or the Vagh-khele performance of Goa.

In the villages of Sundarbans, the legend of Bonbibi is enacted as a stage play (Bonbibi-r Palagaan) to invoke Bonbibi’s blessings.

The tiger remains an integral part of Indian cultural heritage, representing a sense of continuity and pride in the country’s traditions.

🐯 The tiger, the spirit of the jungle, is India’s National animal, a symbol of Man’s yearning for spiritual and emotional well being, harmony with nature and the expression of his artistic creativity through the ages.

Here we can only give a small glimpse to the tigers’ cultural value, there is still much more to discover.

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- Maruvada Surya N. Who is Who in Hindu Mythology. Vol. 2 – 2020.

- Arthur Lillie. India in Primitive Christianity. 1909.

- De Gubernatis Angelo. Zoological Mythology, or, The Legends of Animals, Vol. 1-2. 1872.

- https://www.bhu.ac.in/research_pub/jsr/Volumes/JSR_65_02_2021/1.pdf

- https://ntca.gov.in/tiger-reserves/#tiger-reserves-2

- Divyabhanusinh, Lions, Cheetahs, and Others in the Mughal Landscape, in: Mahesh Rangarajan, K. Sivaramakrishnan. Shifting Ground: People, Animals, and Mobility in India’s Environmental History. 2014.

- Guy Chalk. A World of Stark Realities and the Rule of Tooth and Claw: Jim Corbett and Late Colonial Rule in British India. 2013.

- https://www.harappa.com/blog/deity-fighting-two-tigers-seal

- https://www.harappa.com/content/Ancient-Cities-of-the-Indus-Valley-Civilization

- https://www.harappa.com/sites/default/files/pdf/Parpola_A_2011_unicorn%20%281%29.pdf

- https://www.harappa.com/indus3/185.html

- https://www.harappa.com/sites/default/files/pdf/Ameri-%20Regional%20Variation%20in%20the%20Indus%20with%20front%20matter.pdf

- Sacred animals of India. https://magazines.odisha.gov.in/orissareview/oct2004/englishPdf/lionmount.pdf

- https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in:8443/jspui/bitstream/10603/285530/1/karabi%20kanungo_thesis.pdf

- Balaji Gopalakrishnan et al. Lion and Half man Half animal deities in the Indus valley Civilization. Journal of Indian History and Culture.https://journalcpriir.files.wordpress.com/2020/03/2011-journal-17th-issue-for-web.pdf

- Williams George M. Handbook of Hindu Mythology. 2003.

- https://www.bradshawfoundation.com/india/central_india/index.php

- Jampa Chisky Ven. Symbolism of Animals in Buddhism. Buddhist Himalaya. 1988.

- Burton Adrian. Lion of India. Ecological Society of America. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2011.

- Mohanty, Prasanna Kumar. Encyclopaedia of Primitive Tribes in India. Vol. 2. 2004.

- R.V. Russell. Tribes and castes of the Central Provinces of India Vol. II.

- Vidya Athreya. Monsters or Gods? Narratives of large cat worship in western India. 2018.

- Waghoba

- Nair, Dhee, Patil, Surve, Andheria, Linnell and Athreya. Sharing Spaces and Entanglements With Big Cats: The Warli and Their Waghoba in Maharashtra, India. 2021.

- Mishra, C., Young, J. C., Fiechter, M., Rutherford, B., and Redpath, S. M.. Building partnerships with communities for biodiversity conservation: lessons from Asian mountains. 2017.

- Shaikh Ashraf. Sacred Stripes: Reverence for Waghoba in Central India.Conservation. 2024.

- Thapar, Valmik. The Cult of the Tiger. Sanctuary. 1995.

- https://www.hiedracenters.com/clubdeingles/a-concise-history-of-tiger-hunting-in-india/

- Pande Badri Datt. History of Kumaun (English version of Kumaun Ka Itihas) Vol 1 by 1993.