At Bardia National Park in Nepal, a lone rhino swishes out the elephant grass. We stand very near, quite at the riverbank peering behind tall grass, hearing – observing – now it is slowly reaching the water, peacefully munching. Floating happily into the river. Discover Myth & Folklore of the One-horned rhinoceros also known as the Indian Rhinoceros.

In this Article

The peaceful Rhinoceros

Hindu Mythology

The earliest literary reference to the Khadga, as the rhino is called in Rig Vedic verses, speaks of the armour like hide of the animal. This was used to festoon the world – beating weapon that Arjuna wields in the Mahabharata.

Otherwise, known as the Gandiva गाण्डीव, after Gandaka, the Sanskrit word for rhinoceros, the divine bow – hued bow was given by Varuna, the Lord of the Waters, to Arjuna, the Pandava prince, on the eve of the latter’s Khandava Forest adventure with Krishna.

Among the popular avatars (incarnations) of Vishnu, Sweta Varaha is the third. Some say, against popular notion, that Varaha avatar is not a wild boar (or pig) with one horn, but a White Rhinoceros – or better an Elasmotherium, which is an ancestor of the present day’s Rhino. Sweta Varaha is so strong, he restored earth from completely sinking into water.

In the Santi Parva of Mahabharata, Krishna says:

“Assuming, in the days of old, the form of a Varaha (boar or rhino?) with a single tusk (Eka-Sringa or Unicorn), o enhancer of the joy of others, I raised the submerged Earth from the bottom of the ocean.

For this reason I am called by the name of Ekasringa ”.

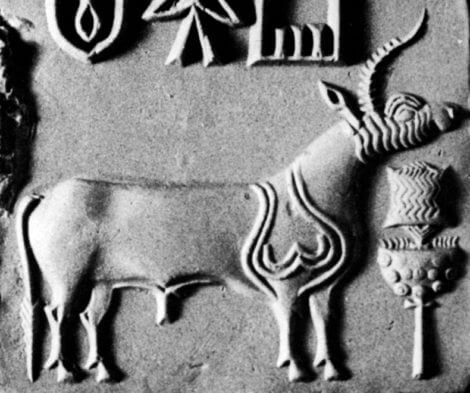

Mahabharata describes the Varaha as shown in the Harappan iconography. Anonymous artists in Indus Valley carved this seals of rhinos into soft steatite.

These perfectly capture the tiniest of details of the animal, including hairy ears and the horny snout upraised in perpetual curiosity. Some archaeologists suggest that these seals were used for commerce purposes, or worn as protective amulets.

This Indus Seal was found between 1927 and 1931 during the initial excavations at Mohenjodaro, an Indus Valley site in Sindh province, modern Pakistan. This Civilization flourished between 2600 and 1900 BC.

The Pashupati seal, showing a seated and possibly tricephalic (3 horned) figure, surrounded by animals; circa 1400-1900 BC- also known as “Lord of the Beasts” Rudra or a Protoshiva?

Buddhist teachings – Be like a Rhinoceros

The lonely furrow, cut into the sea of grass by the rhinoceros, also inspired the Khaggavisana Sutta or the Rhinoceros Sutra of the earliest Buddhist canon.

Because the Asian rhinoceros had one horn, and because lore attributed to it a life alone in the forest, this sutra is aptly titled to present what the translator calls an essay “on the value of living the solitary wandering life.” Specifically, this would refer to the life of the forest monk of Southeast Asia.

In The Sutra the Buddha says one should wander alone like a rhinoceros, – so the recurring line at the end of each verse. The verses also suggests that a non-violent disposition and an intentional lack of desire for companionship are qualities of this animal and should be emulated:

Renouncing violence for all living beings,harming not even a one;You would not wish for offspring,so how a companion? Wander alone like a rhinoceros.

The refrain in this sutra is a subject of controversy. The text literally says, Wander alone like a ‘sword-horn’, which is the Pali term for rhinoceros. The initial portion of Persian kargadan resembles the Sanskrit word “khaRga” for rhinoceros also meaning sword.

On the creation of the Rhinoceros

The grasslands of the Terai continue to be home to a beast said to be created when the Hindu god Vishwakarma was drugged, according to a Tharu folk tale recounted by Hemanta Mishra in his memoir, “The Soul of the Rhino”:

“He picked the best parts of many animals on earth and stitched them together.

His creation had:

- the skin of an elephant,

- the hooves of a horse,

- the ears of a hare,

- the eyes of a crocodile,

- the brains of a bear,

- the heart of a lion, and

- horns like Nandi, Shiva’s bull.

Viswakarma creatively twisted, molded and further modified these parts, even fusing two horns into one.

The result was beyond his expectation, a masterpiece of the art of imperfection.”

Hemanta Mishra

The round studs on the colossus blundering ahead, for instance, remind me of Dürer’s masterpiece of the art of imperfection.

Albrecht Dürer

In 1513, an Indian rhinoceros arrived in Lisbon and created a furor as no one had ever seen this battleship of an animal in the flesh. The German painter and print maker, Albrecht Dürer, never saw the actual rhinoceros, his woodcut is derived from a written description and sketch by an unknown artist.

Despite its anatomical inaccuracies, like the second horn on the back. Dürer’s artwork became very popular in Europe and was copied many times until the late 18th century.

The German inscription on the print is taken from Pliny’s description and vividly paints a picture of a beast as big as an elephant that is a merciless killing machine:

“On the first of May in the year 1513, the King of Portugal, Manuel of Lisbon, brought such a living animal from India, called the rhinoceros. This is an accurate representation.

It is the color of a speckled tortoise, and is almost entirely covered with thick scales. It is the size of an elephant but has shorter legs and is almost invulnerable. It has a strong pointed horn on the tip of its nose, which it sharpens on stones.

It is the mortal enemy of the elephant. The elephant is afraid of the rhinoceros, for, when they meet, the rhinoceros charges with its head between its front legs and rips open the elephant’s stomach, against which the elephant is unable to defend itself. The rhinoceros is so well-armed that the elephant cannot harm it.

It is said that the rhinoceros is fast, impetuous and cunning”.

The Dürer Rhino depicts an awe-inspiring animal adorned with impenetrable armored plates and an extra horn jutting from its shoulder. To this day the Indian rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) 🦏, is called Panzernashorn (armoured rhino) in the German language because its skin looks like the plates of a knight’s armour.

“The Rhinoceros looks so peaceful”, I say, “They might look like now. Males can become violent within their territories if a lesser male infringes on a female in heat.

In mating season, they can run for hours, that’s- when they really get dangerous. Running down everything standing in their pad, houses, people, trees,” Rajan Chaudhary says.

Showing deep holes on the ground he adds, “and this is the mating place”. I can clearly see the four holes where the feet supposed to stand – vividly imagining how he rested his head on her back before lifting his 2 ton bulk up and placing himself on her back – a heavy work.

The fighting Rhinoceros

E.P. Gee considers the rhino to be the actual ‘king of the beasts’. This is so because both elephants and tigers are afraid of this creature. Tigers never dare to attack adult rhinos although, if they catch a mother off guard, they carry off rhino calves.

Lao-tse (Tao Te Ching, chapter 50, para. 4):

“But I have heard that he who is skillful in managing the life entrusted to him for a time travels on the land without having to shun rhinoceros or tiger, and enters a host without having to avoid buff coat or sharp weapon.

The rhinoceros finds no place in him into which to thrust its horn, nor the tiger a place in which to fix its claws, nor the weapon a place to admit its point. And for what reason?

Because there is in him no place of death.”

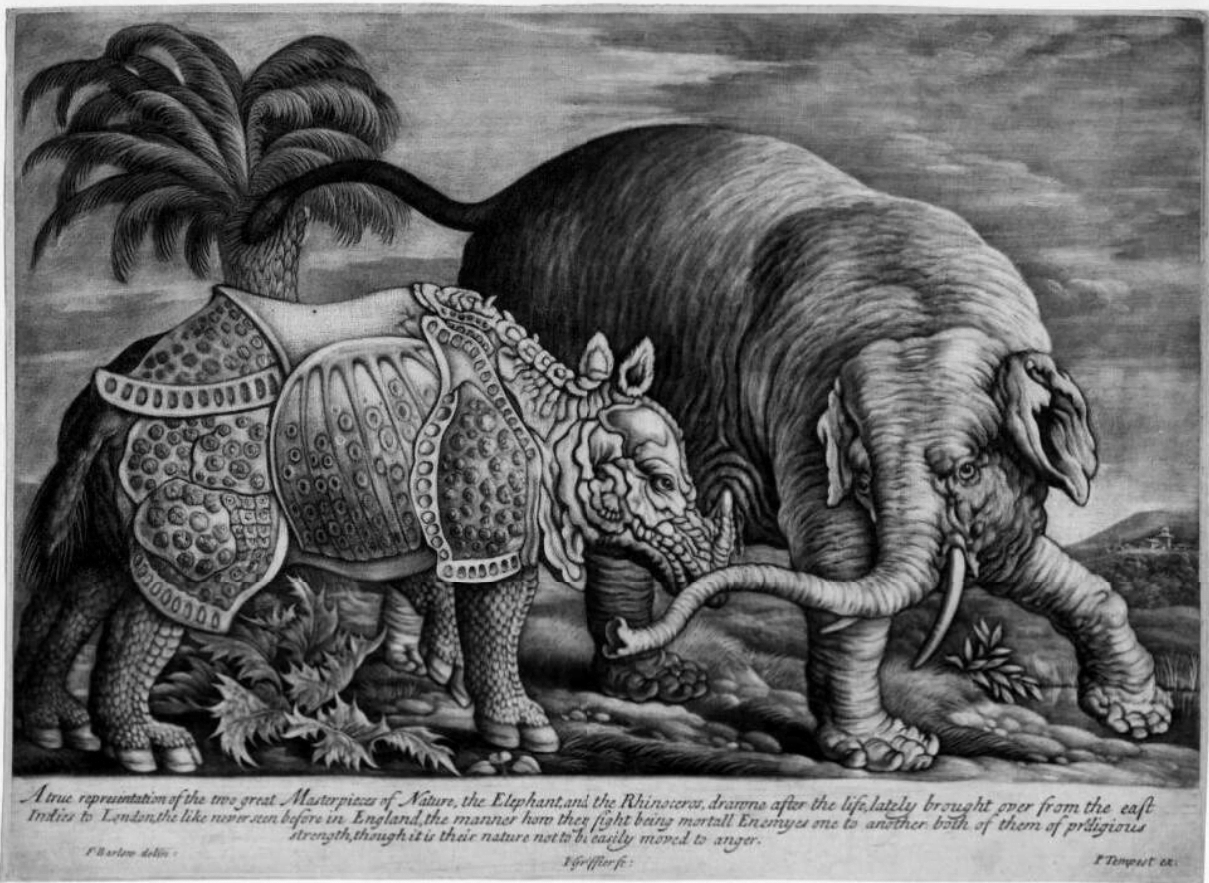

Battles between rhinos and elephants were a popular spectacle for centuries, adding to the pomp and ceremony of gladiatorial games.

The procurement and exchange of exotic animals has been traced back to both, the Egyptians (2500 BC ) and the Greeks (seventh century BC ), and increased significantly during Roman times where animals were used for blood sport in the Amphitheater games from 186 BC to the last games in 523 AD Cassius Dio’s Roman History describes games in the Circus wherein

an elephant overcame a rhinoceros.

It was a powerful visual interpreted by artists, centuries apart, the rhinos body covered in plated armor. In reality the tough skin of the tank-like creature is bare except for a fringe of whiskers around the ears and at the tip of the tail.

Inscription Content: Lettered below the image:

“A true representation of the two great Masterpieces of Nature, the Elephant, and the Rhinoceros, drawne after the life, lately brought over from the east Indies to London, the like never seen before in England, the manner how they fight being mortall Enemyes one to another:

both of them of prodigious strength, though it is their nature not to be easily moved to anger.” [sic]

F. Barlow and Jan Griffier (1685)

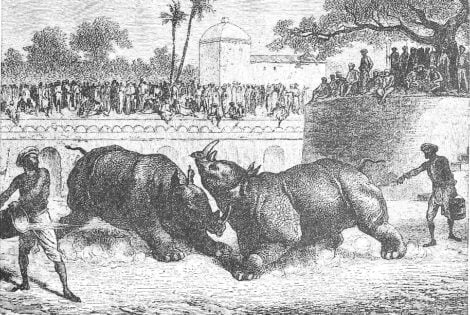

In his account of Lucknow, Abdul Halim Sharar (1860 – 1926) states that at the time of Nasir ud Din Haidar there were fifteen or twenty fighting rhinoceroses kept at Chand Ganj. Further, at the time of King Ghazi ud Din Haidar, some rhinoceroses, besides being made to fight, were supposedly so pacified that they were harnessed to carts and mounted by riders.

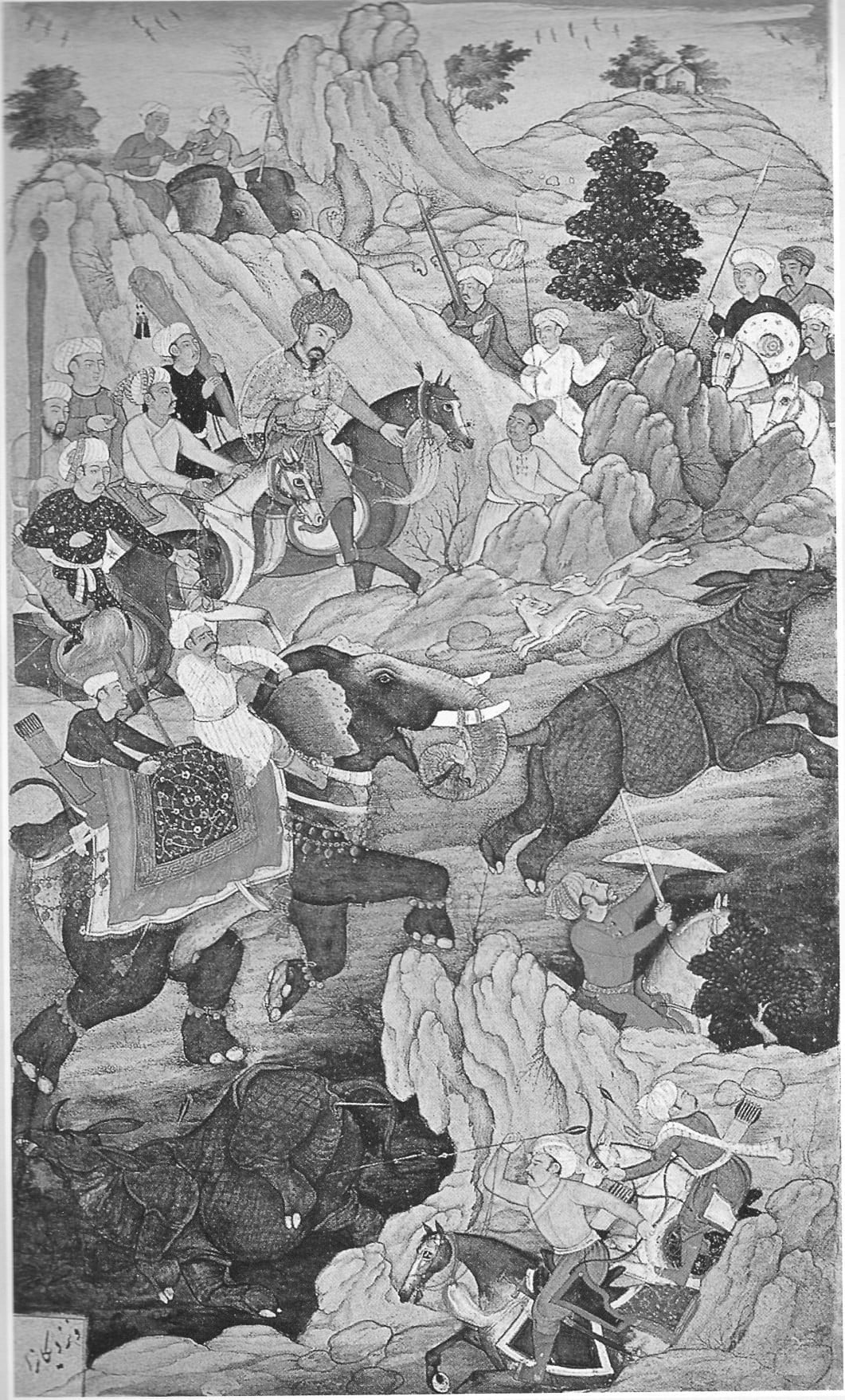

Many fine representations of the hunt of the rhinoceros survive in medieval art, in the Islamic world, India, Nepal and in China.

Rookmaaker, Vigne and Martin provide commentary on rhinoceros fights in India in considerable detail. An account of Mogul Emperor Shah Jahan (1627–1658) states that the ruler would

witness contests between elephants and other wild animals, such as lions, tigers, rhinoceros, and wild buffaloes.

Elephants and Rhinoceros seldom get together in the wild.

The authors elaborate on the description of Nasir ud Din Haidar, adding that the rhinos were prepared for battle by ingesting stimulants and that rhino–rhino fights were a regular pastime in the 1820s. They also refer to two later incidents in Baroda (Vadadora) in 1864 and 1875.

The first was recounted by the French traveller Rousselet in his 1877 book entitled “L’Inde des Rajahs”, including a particularly detailed description of a typical fight where opposing rhinos were chained at opposite end of the arena with their horns painted either black or red to aid spectators in distinguishing between the opponents.

In the second, in November 1875, the Rajah was entertaining the Prince of Wales when the rhinos withdrew from combat after a few passes and could not be convinced to continue even when attendants proceeded to throw cold buckets of water onto the competitors and thrust at them with lances.

Despite having dagger-like horns, rhinos hardly use them for offense and defense. When an Indian rhino defends itself against a predator or another rhino, it doesn’t use its horn to gore its opponent. Instead, it slashes and gouges viciously with the long, sharp incisors and canine teeth on its lower jaw.

They would bite off chunks of flesh from their opponents body using their sharp teeth. However, African cousins like the black rhinos do use their horns when annoyed.

The Rhinoceros is not a fighter, it is rather a loner. It’s skin possesses rivet-like tubercles and is folded at various places giving the appearance as if the animal is wearing armor.

The more enigmatic the animal is the more myths are associated with it. It is said that rhinos are bulletproof. In a ridiculous case of rhino hunting in Assam, the hunter claimed that he shot at the rhino only to verify if it was really bulletproof as he had been told!

Thick skin – How the Rhinoceros got his armor plating

Edward Pritchard Gee recounts an ancient Indian myth that explains the “armour plating” of the rhino.

It is said that, once, Lord Krishna decided to use rhinos in place of elephants in battle. However, when the creature, all covered in armour for battle, was brought in, it was found to not obey commands. Therefore, it was sent back to the forest. Unfortunately, they forgot to take off its armour – and so it remains until this day.

It was also this species of rhino that inspired the English writer Rudyard Kipling to write “How the Rhinoceros got his Skin”, in 1902. Therein, a Parsee man rubs cake crumbs into a rhino’s skin, causing it to itch and scrape itself up against a palm tree, creating the vast folds of skin it bears today.

The skin of the Rhino is thick but extremely sensitive to heat and sunburn. This is one of the reasons why the rhinos we are seeing wallowing in the river to cool off and prevent their skin from sunburns.

Other reasons being parasite prevention, changing taste with aquatic plants in the menu and salt licks in certain cases. Watching the birds cleaning the Rhinoceros skin is a pleasure and a feast for our eyes.

The rhino is a homely beast,

For human eyes he’s not a feast.

Ogden Nash wrote in his famous ode to the ‘prepoceros’ beast. We beg to differ with the master of pun poems and also with British naturalist Charles Hose, speaking of the Sumatran Rhinoceros he described ‘the beast’ in 1929 as the most grotesque of his kind.

The rhino’s armour- plated mystique has captivated artists and poets alike throughout centuries as well as it’s horn.

Which kind of animal is meant on this seal?

The body is clearly bovine, but the neck is too long, and the head too narrow. And what are those strange lines on the shoulder and the neck? Perhaps the people of the Indus valley, had seen the Elasmotherium [extinct forefather of the Rhinoceros] along the rivers… or the civilization of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro, have depict a Black Buck, a Tibetan Antelope, a Nilgal or an Aurochs? It could very well be also representation of what was already a mythological animal – the Unicorn.

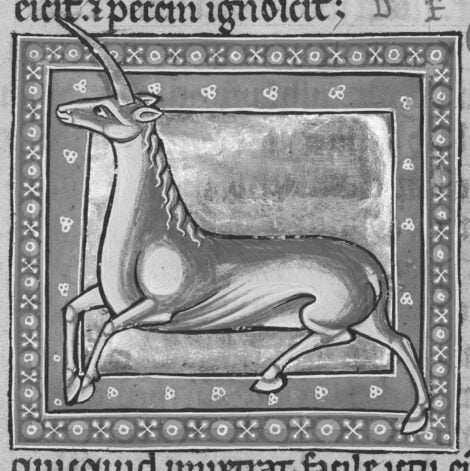

The Unicorn

The unicorn has always been viewed by cultures in Europe, West Asia, and China and Japan as a mythical animal or at least something that is fantastic and rare. Probably the earliest representation of a unicorn is found on seals and sealings from sites in the northern Indus region (Harappa and Mohenjo-daro), dated to ~ 2600 BC This motif is not reported from any other contemporaneous civilization and appears to be unique to the Indus region.

The unicorn motif continued to be used throughout the greater Indus region for over 700 years and disappeared along with Indus script around 1900 BC. The discovery of one-horned animal motifs on seals and one-horned animal figurines in terracotta has been the source of typological and terminological controversy.

The single horn in the middle of its forehead is the basis for the legend of the unicorn. The historical unicorn is but myth and legend, though one-horned animals do seemingly exist.

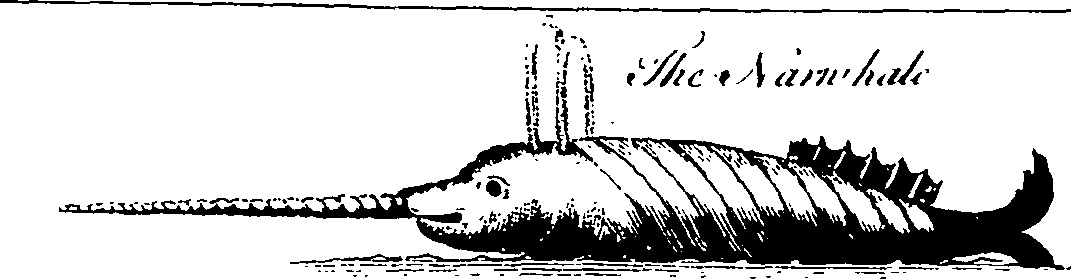

The Rhinoceros horn was confused in medieval European times- where a marine version, arose – the Narwhal (Monodon monoceros), or narwhale, a medium- sized whale whose tusk resembles a horn and was once known as a “sea unicorn”.

In Mediaeval sources the horn of the unicorn is evidently the tusk of a narwhal. This confusion arose very early, as may be seen from its occurrence in Aelian, who says that the horn of the unicorn or Kartazonon (the Arab Karkaddan or Rhinoceros) was not straight but twisted (Greek: eligmous echon tinas).

The mistake may also be traced in illustrations and drawings, and it long endured. In fact, in Europe until the 18th century, rhino and Narwahl horn was sold as unicorn horn.

Etymology: Rhinoceros

The Indian Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) also referred to as the ‘Greater-One Horned Rhino’ is native to India, China and Nepal and regionally extinct in China, Bangladesh and Bhutan.

Rhino means “nose” in Greek, and “ceros” is “of horn” and Latin “unus” meaning single and “cornu” meaning horn. However, it is not a real “horn” and not actually attached to the skull, but is composed of keratin, like our hair or fingernails.

Historical accounts

Ctesias – Indian ass

The earliest description in Greek literature of a single-horned (Greek monokerōs, Latin unicornis) animal was by the historian Ctesias (c. 400 BC), who related that:

“the Indian wild ass was the size of a horse, with a white body, purple head, and blue eyes, and on its forehead was a cubit-long horn coloured red at the pointed tip, black in the middle, and white at the base. Those who drank from its horn were thought to be protected from stomach trouble, epilepsy, and poison. It was very fleet of foot and difficult to capture.”

The actual animal behind Ctesias’s description was probably the Indian rhinoceros.

Aristoteles – Indian ass

Aristoteles was the next significant author to describe what he called the Indian ass in “The History of Animals”. He adds to Ctesias’ work, identifying the Indian Ass as the only creature to have solid hooves and a knuckle-bone:

“there are … some animals that have one horn only, for example, the oryx, whose hoof is cloven, and the Indian ass, whose hoof is solid. These creatures have a horn in the middle of their head.”

Pliny the Elder – Monoceros

Next was the renowned Roman encyclopedist, Pliny the Elder, who compiled the records of one hundred authors in his “Natural History“.

Of all the classical accounts”, it was Pliny’s that proved the most influential, with an impact spanning over 1500 years.

Pliny’s account of a “Monoceros” was published in 77 :

“the Orsaean Indians hunt an exceedingly wild beast called the Monoceros,

which has a stag’s head, elephant’s feet, and a boar’s tail, the rest of the body being like that of a horse…

with a single Horn on his Snout…”

The Bible – Reʾem

According to the book of Genesis, God gave Adam the task of naming everything he saw. In some translations of the Bible, the Unicorn was the first animal named; thereby, elevating it above all other beasts in the universe.

Reʾem was translated “unicorn” or “rhinoceros” in many versions of the Bible, but some translations prefer “wild ox” (auerochs), which is the correct meaning of the Hebrew reʾem.

When Adam and Eve left paradise, the Unicorn went with them and came to represent purity and chastity. Thus, the Unicorn’s purity in the Western legends could stem from its Biblical beginnings.

The ancient Greek bestiary known as the Physiologus, states that the unicorn is a strong, fierce animal that can be caught only if a virgin maiden is thrown before it. The Mahabharata and Ramayana tell a similar story –

Rishyashringa – Known to Buddhists as Ekasringa

The story of the young boy Ṛsyasrńga or Rishyashringa is given in the Ramayana, Puranas and the Mahabharata with some variations.

A forest Rishi (ascetic) lived in the forest. A doe drank water mixed with his semen, fell in love with him, and gave birth to a male child named Isisinga (= Pāli form of Sanskrit Ṛṣ yaś ṛṅ ga ‘Antelope-horn’ or Rishyashringa).

The boy had a small protuberance on his forehead, whence his name.

When the boy came of age, his father warned him against the wiles of women, initiated him into the practice of asceticism, and died. Isisinga practiced such fierce asceticism that Indra [the king of gods], fearing that the sage would depose him, sent the apsaras [heavenly nymph] Alambusā to seduce him.

When Isisinga saw her, he immediately desired her and pursued her; she embraced him and his chastity was destroyed.

For three years he made love to her, but then he realized that he had neglected his duties. He gave up the path of desire, and he forgave and blessed the apsara. When she returned to heaven, Indra offered to grant her any wish, and she chose never to be made to tempt another sage.

The Mahabharata, explains the horn in the following stanza:

“O lord, there was a single horn of a rsya on the head of the great being. For this reason, he became known as Rishyashringa”

He is mentioned in Buddhist texts as Ekasringa (unicorn). The story also resembles the Sumerian story of “Enkidu” from the Gilgamesh epic.

Enkidu, a half human and half animal was born of a gazelle and was civilized by a courtesan. Possibly with this myth the idea of capturing Unicorns with a virgin maiden has its start.

Genghis Kahn – Chüeh-tua

As Chinggis, Kengis Khan or Genghis Khan and his army prepared to invade for what would probably have been an easy victory, a Unicorn approached and knelt before him and India was saved from invasion.

Chinggis Khan and the talking rhinoceros of India

In the winter of 1221-1222 an unusual encounter between man and beast took place in the Punjab region of India. Chinggis Khan’s imperial guard while probing southwards in India were held in awe by the sight of an extraordinary creature.

The Mongol imperial guard reported seeing, a one horned animal with a body like a deer, but with a horse’s tail and green in color which addressed the imperial bodyguard in human speech saying,

“Your master should return home as soon as possible!”

This passage is quoted from the biography of Yeh-lü Ch’u-ts’ai’s biography in the Yüan-shih, a Chinese account of the period of Mongol rule. Yeh-lü Ch’u-ts’ai, an important advisor to Chinggis Khan reported this incident to the Emperor who raised questions about the meaning of this episode. He explained it thus,

“This is an auspicious animal called chüeh-tua. It is capable of speaking all the world’s languages, it loves life and abhors bloodshed. This is a happy omen sent down by Heaven to warn your Majesty. You are Heaven’s eldest son, and all the men under Heaven are your children. Pray accept the will of Heaven and preserve the people’s lives.”

That very day the Emperor withdrew the army.

Man and beast are seldom involved in the realm of diplomacy, but in this case the fate of a nation might well have rested on the horn of a rhinoceros.

Marco Polo – Unicorn

In the late 1200s, though, Italian trader Marco Polo became famous for his accounts of travel in China and Southeast Asia. He reported seeing a large Unicorn in Java, almost as big as an elephant.

There are wild elephants in the country, and numerous unicorns, which are very nearly as big. They have hair like that of a buffalo, feet like those of an elephant, and a horn in the middle of the forehead, which is black and very thick.

They do no mischief, however, with the horn, but with the tongue alone; for this is covered all over with long and strong prickles [and when savage with any one they crush him under their knees and then rasp him with their tongue].

The head resembles that of a wild boar, and they carry it ever bent towards the ground. They delight much to abide in mire and mud.

‘Tis a passing ugly beast to look upon, and is not in the least like that which our stories tell of as being caught in the lap of a virgin; in fact, ’tis altogether different from what we fancied.[sic]

His detailed description was almost certainly a rhinoceros, but the retelling of his tales and the illustrations that accompanied them usually made the Unicorn fit in with the traditional horse – like creature.

While the legendary unicorn evolved in the West, in the Far East, similar creatures where long known in mythology and folklore.

In China, the qilin had quite a different disposition.

It harms no creature, and its presence is considered a good omen.

Reportedly, a qilin appeared to Confucius‘ mother before he was born.

The Japanese unicorn, or kirin (after which the beer is named) is a fierce creature able to root out criminals, instantly punishing them by piercing them through the heart with its horn.

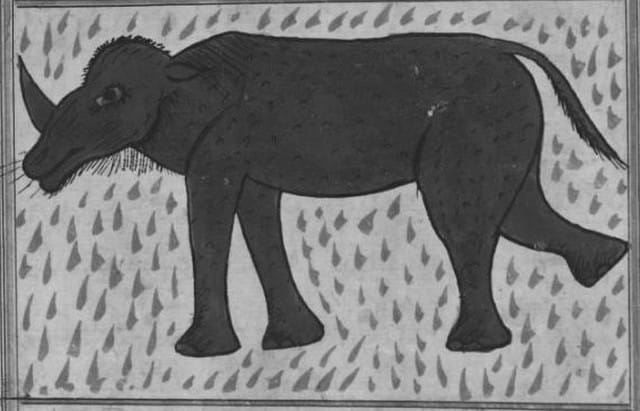

Al-Biruni – Karkadann

The Persian Karkadann, meaning ‘lord of the desert’, for instance, refers to a horned mythical creature that’s said to have lived on the grassy plains of Persia and India.

An early description of the karkadann comes from the 10/11th century Persian scholar Abū Rayḥān al-Bīrūnī (973–1048). He describes an animal which has

“the build of a buffalo…a black, scaly skin; a dewlap hanging down under the skin. It has three yellow hooves on each foot…

The tail is not long. The eyes lie low, farther down the cheek than is the case with all other animals. On the top of the nose there is a single horn which is bent upwards.”

A fragment of Al-Biruni preserved in the work of another author adds a few more characteristics:

“the horn is conical, bent back towards the head, and longer than a span…

the animal’s ears protrude on both sides like those of a donkey, and…

its upper lip forms into a finger-shape, like the protrusion on the end of an elephant’s trunk.”

These two descriptions leave no doubt that the Indian Rhinoceros is the basis for Al-Birunis description.

Later, in medieval times, scholars took his description and formed ever more fanciful versions of the beast, aided by the absence of first-hand knowledge and the difficulty of reading and interpreting old Arabic script. It has been conjectured that the mythical karkadann may have an origin in Rishyashringas account from the Mahabharata.

The creature, which earlier was synonymous with the rhinoceros, turned into a veritable chimera. Like the unicorn, it was deemed as capable of being subdued by virgins and worse, its horn was endowed with the strangest sort of mythic-medicinal properties.

The use of the Rhinoceros — a sacred animal

Ancient Hindu Rituals

The earliest mention of the rhino was that of Kalikapurana where sacrifice of the rhinoceros, which was in practice in the Kamakhya temple, had been described.

“The flesh of antelope and rhinoceros give my beloved (kali) for five hundred years”

Kali Purana

The rhinoceros is found also in Manu- smriti or Manava-dharma-shastra, dating from circa 100 C.E. and was used for Sadhra ceremonies, as an offering to the forefathers, using it’s warm blood drawn from the stomach immediately after death or the flesh.

The King of Nepals Blood Tarpan religious ceremony

Esmond Bradley Martin explains the ritual sacrifice of the rhino:

On 9 January 1981, when rhinos were no longer endangered, the king of Nepal was able to perform a sacred rite that all Nepalese kings are obliged to do once in their lifetime.

This is the blood Tarpan (sacrifice) ceremony, and it consists of offering rhino blood libations to the Hindu gods.

King Birendra, accompanied by Queen Aishwarya, other members of the royal family and several Hindu priests, were mounted on elephants and led by the Park’s people, also on elephants, to a large male rhino outside the Park’s northern boundary.

Altogether 26 elephants were used to encircle the rhino to prevent its escape and to allow the King to shoot it at close range. On the following morning, the fallen beast was dragged to the Rhapti river near Kasara, where a group of men disemboweled it.

The King, dressed in a simple white robe, entered the abdominal cavity, knelt down and filled his cupped hands with rhino blood, which he offered to his gods in memory of the late King Mahendra, his father. Hindu priests chanted prayers throughout the ceremony of the rhino sacrifice.

Although this little known rite may appear a negative factor for rhino conservation, it actually is a major impetus to make certain that rhinos are plentiful enough to allow its performance, which is regarded as an extremely important event.

It is carried out just once in a king’s life and only a mature male rhino, never a female, is sacrificed. A small price to pay in return for the protection granted to the rhino population as a whole, it epitomizes the role of religion and royalty in Nepal’s rhino conservation.

Ethnomedicine of the Tharu people

As detailed in conservationist Hemanta Mishra’s 2008 memoir, “The Soul of the Rhino”, Nepalese have long viewed the rhino with curiosity and reverence. Chitwan’s indigenous Tharu people have attached particular respect to rhinos.

The Tharu have been using rhino products for many generations. When a rhino dies of natural causes in the Chitwan valley, the park authorities remove the horn and hooves, which are royal trophies. All rhino horn and hooves will be sent to the King’s Wildlife Office inside the palace in Kathmandu.

The hide

Today the most widely used rhino commodity in Nepal is the hide, which plays a most important role in an elaborate religious ceremony, called Shradda, performed by both Hindus and Buddhists in Nepal to commemorate parents or grandparents on the anniversary of their deaths.

It is believed that a piece of horn or skin, shaped into a container to hold rice, water and some flowers, will attract the attention of the spirit of the dead. Although rhino horn preferred to skin in this ritual, no one other than the King himself is allowed to possess any horn in Nepal now (unless it is an antique carving).

The blood

The blood is dried it in the sun to preserve it. Women are the main consumers of rhino blood; they mix it with water to drink to ease menstrual pain; but men also occasionally swallow some as an aphrodisiac.

The meat

While they reportedly refrained from hunting the animals, some Tharus gathered the meat from carcasses. Although they will not touch the flesh from any other decaying animal.

Rhino meat, which is usually cooked with mustard oil, sliced tomatoes and curry powder, is believed to confer immunity to serious diseases. The meat also is believed to offer health, courage and strength. Rhino liver is eaten to cure tuberculosis, dysentery and, occasionally, to speed up the elimination of after-birth.

The bones

The bones are also very important and the most desirable is that from the knee-cap, which is fashioned into an oil lamp for use during religious festivals. Other bones are carved into finger rings to keep away evil spirits.

Some are made into charcoal, the fumes of which are believed to cure diseases among penned cattle.

In some cases, the penis from a dead rhino is taken. “I saw a few dried ones for sale in Kathmandu, and I was told that older men boil them in water and eat them to try to cure their impotence.

A few people use them like the umbilical cord, tied around their middle to alleviate stomach pains.

In Bodhnath, a shopkeeper showed me the jaw from a rhino, and he said that votive statues of gods and goddesses are carved from rhino teeth, although I never saw any,” Esmond Bradley Martin explains.

The urine

Such uses for rhino body parts have long been barred under current conservation law, but the Tharu still eagerly gather rhino urine, long considered a remedy. Substantial quantities come from the animals in captivity in Kathmandu’s Zoo, and Chitwan park employees often collect it in the field. Esmond Bradley Martin point out:

“Whenever my elephant handler took me out he carried a bottle with him. When we came across a place where a rhino had recently urinated he gathered up the liquid or, if it was embedded in sand, he stuffed the sand into his bottle.

He explained that he would later place the sand in a strainer and pour a little water through it to extract the urine. The diluted urine, he maintained, was still useful.”

Others collect the urine with sponges or cloth we are told in Chitwan National Park.

Some Tharu people drink rhino urine as a relief from asthma attacks, congestion and stomach disorders, apply it to the skin to prevent infection in wounds and soothe sore muscles, and sometimes put drops of it inside the ear to relieve earaches.

The dung

From two different sources, I heard that rhino dung can be mixed with pipe tobacco and smoked to alleviate stomach pains. Some locals grow (magic) mushrooms on the dung.

Tharu people also believe that keeping a horn under a pregnant woman’s pillow would allow for a quick and smooth delivery.

ETHNOMEDICINE: The precious horn

Asko Parpola suggests, that the Harappan Unicorn seal, was an integral part of unicorn mythology for the Indus civilization. The unicorn stood for male creative power, and that its cult purported to secure rain and fertility for purposes of agriculture and animal husbandry.

The single “Horn” or “Tusk” of the rhinoceros in Sanskrit is śrnga– and its derivative ; śrngara – has as one of its principal meanings as a phallic symbol of erect virility, it stands for erotic love and sexual passion.

Zakariya al Qazwini

Zakariya al Qazwini, the thirteenth century Persian polymath, was among the earliest authors to claim that rhino horn was a potent antidote to poison. He also noted that it was used in embellishing knife handles.

Aphrodisiac

The entirely fictional association of the animals’ horn with aphrodisiac and restorative properties has brought many rhino species almost to the brink of extinction.

Up until recently, rhinoceros horn was used as an aphrodisiac by the Gujarati community in India, with contemporary evidence now suggesting that some is being used for this purpose in Vietnam, consumed as tuu giac (rhino wine) as a sexual enhancer for men.

However, other parts of the rhino are used for aphrodisiac purposes. For example, some people from northern India, Nepal, Burma, and northern Thailand consume rhino blood, urine, and penises for sexual enhancement. Further, in Nepalese medicine, the penis is sold dried and then re-hydrated and consumed to cure impotence.

Chinese, Burmese, Thai and Nepalese practices utilize a variety of rhino parts whereas Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese communities exclusively use the horn.

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) and the use of the rhino horn

Records show that horns were described as tongtian – a term denoting extraordinary properties and even a passage to heaven. Called “dragon’s tooth” and seen as one of the “eight treasures”. The use in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) is found in the Baopuzi by Ge Hong, the most widely cited source that explains these qualities:

“The horn can part water, providing safe passage across rivers. It is also known to scare chickens when employed as a vessel for their feed, a property that extends to frightening other birds, and in other sources even to foxes.

The horn can also aid in keeping courtyards free of moisture, and is luminescent. Elsewhere the rhinoceros horn is said also to dispel dust.

Hong also suggests that the horn may be used as an antidote for poison arrow wounds as well as for poison detection generally.

As a technique to acquire the valued tongtian horn, Hong encourages readers to locate a spot where a rhinoceros ‘sheds and drops their horn’ each year, make a replica out of wood and return it to that spot as a substitute, allowing them to take the true horn and ensure that the rhino returns to shed at that spot the following year.” [sic]

The translation from 1931 of Li Shih-Chen’s 1597 “Materia medica“, Pen Ts’ao Kang Mu explains the plethora of symptoms and afflictions rhino horn was alleged to remedy.

- It should not be taken by pregnant women; it will kill the fetus.

- As an antidote to poisons (in Europe it was said to fall to pieces if poison were poured into it).

- To cure devil possession and keep away all evil spirits and miasmas.

- For gelsemium [jasmine] and snake poisoning.

- To remove hallucinations and bewildering nightmares.

- Continuous administration lightens the body and makes one very robust. For typhoid, headache, and feverish colds.

- For carbuncles and boils full of pus.

- For intermittent fevers with delirium.

- To expel fear and anxiety, to calm the liver and clear the vision.

- It is a sedative to the viscera, a tonic, antipyretic.

- It dissolves phlegm.

- It is an antidote to the evil miasma of hill streams.

- For infantile convulsions and dysentery.

- Ashed and taken with water to treat violent vomiting, food poisoning, and over dosage of poisonous drugs.

- For arthritis, melancholia, loss of voice. Ground up into a paste with water it is given for hematemesis [throat hemorrhage], epistaxis [nosebleeds], rectal bleeding, heavy smallpox, etc.

More Uses:

In Yemen and Oman, showing off daggers with handles made of rhino horn is a sign of health. The older handles being more valued, as they get a translucence similar to amber.

Especially cups from rhino horn were used in Asia, said to help against poison or to clean the water. Entire body parts are featured in the US or Europe, as elements of decoration – a set of feet for a bed or table, a head for over the fireplace, the skin on the floor.

Note: This post does not contain medical advice.

Ethnomedicinal knowledge plays a crucial role in indigenous healthcare systems. Various critically endangered (CR), endangered (EN), vulnerable (VU), near threatened (NT), and vulnerable (VU) vertebrate species (listed on the IUCN Red List) are being used and traded for traditional medicinal purposes.

Education and awareness programs can inform community members about alternative

treatment options, such as the use of medicinal plants or locally more available species ,

inspite of using endangered species.

Collaboration between traditional and western medicine systems can also provide holistic healthcare solutions that respect both cultural beliefs and conservation objectives.

However, interventions must be implemented with cultural sensitivity, involving local communities in decision-making.

Conservation

The rhino huffing and puffing ahead of us represents one of the great conservation success stories of the twentieth century. The cultural significance of the Indian Rhinoceros in The Terai Duar Savanna and Grasslands of India and Nepal is inextricably linked with the region’s colonial past.

The species was on the brink of extinction in the early 1900s, due to the mass conversion of alluvial plains grasslands to agricultural development and deforestation for timber.

“Reports from mid-nineteenth century claim, for instance, that many British military officers in Assam had bagged as many as 200 ‘trophy animals’ individually!

No wonder Kaziranga was left with just 12 rhinos in 1900. Only with strict protection and enlightened management did the numbers recover somewhat.”

We are told by Rajan Chaudhary in Bardia National Park. In Nepal the royal family, on the other hand, valued the animals as dangerous and thrilling quarry for sport hunting.

Upon overthrowing the Shah dynasty in 1846, Jung Bahadur Rana, the founder of the country’s last royal line, declared the rhino a “royal animal” that only the ruling family and its guests could pursue. The same year, Chitwan was established as a private hunting reserve.

Subsequently, Nepalese royalty and visiting European dignitaries slaughtered, according to Mishra, 39 tigers and 18 rhinos in 1911. Lord Lithgow, Britain’s viceroy to the Indias hunt, saw 120 tigers, 27 leopards, 15 bears, and 38 rhinos being massacred, in 1938. It was not until 1972 that hunting was outlawed in Nepal except in one reserve in the Himalayas.

“Blame it all on over hunting and extensive loss of habitat,”

Rajan Chaudhary, our friend adds, sipping on the home made rice wine (Roksi) his kind wife did bring us.

Recognizing the urgency to avert the erratic diminishing of one-horned rhinoceros, the royal family and the Government of Nepal formulated the “Gainda Gasti”, am armed Rhino Patrol Unit in 1961, and declared the remaining prime rhino habitats, about 544 sq. km along Rapti, Narayani and Reu rivers, as the Chitwan National Park in 1973.

When the first protected areas were established in Chitwan, indigenous Terai communities, like the Tharu, Bote, Darai and Mushar, were forced to relocate from their traditional lands. They were denied any right to own land and thus forced into a situation of landlessness and poverty.

When the national park was designated, Nepalese soldiers destroyed the villages located inside the boundary of the park, burning down houses, violating woman and trampling fields using elephants. The Tharu people were forced to leave at gun point.

The same happened to local communities on the bordering Indian Terai National Park territories. During a visit to the Tharu museum in Sauraha, we been captivated by an exhibit about individual experiences of the Tharu communities living outside of the National Park in “Buffer Zones.”

There are accounts of houses being burned and army officials dragging mothers and children away in extremely violent ways.

Later the Chitwan park was extended to total coverage area of 932 sq. km and was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1984 for its richness in wildlife. More Nationalpaks were established, Sukla Phanta Wildlife Reserve, Bardia and Dudhwa, Tigers, Elephants and Rhinos are exchanged between the parks.

In 1996, an area of 750sq km surrounding Chitwan National Park was declared a buffer zone, which consists of forests and private lands including cultivated lands. The buffer zone contains a Ramsar Site – Beeshazari Lakes.

The park and the local people jointly initiate community development activities and manage natural resources in the buffer zone. The government of Nepal has made a provision of plowing back 30-50 percent of the park revenue for community development in the buffer zone – money for the Tharu communities.

Also in India the organization of what is now Kaziranga National Park became a reserve in 1905. It was build for the last ten to twenty Indian rhinos in Assam, and was found to be home to seventy per cent of the global species population in May 2007.

In 1910 the government officially outlawed rhino hunting, although poaching remained a constant threat to recovering populations.

Rivaling the price of gold on the black market, rhino horn is still at the center of a bloody poaching battle.

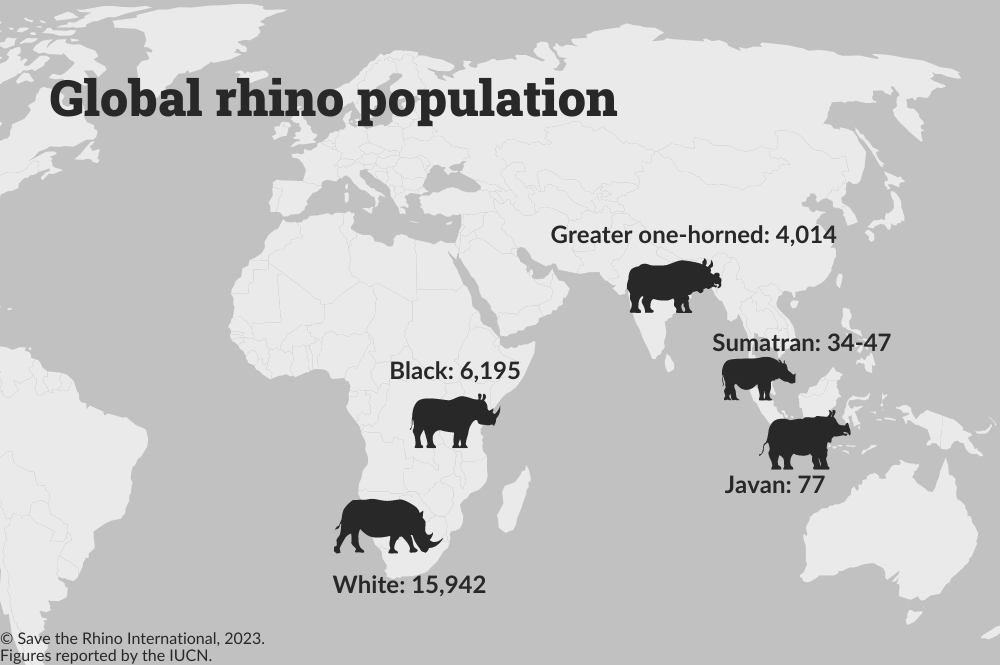

Of the five species of rhinoceros, Javan and Indian rhinos are one-horned, whereas the white, black and Sumatran rhinos have two horns. Compared to 500,000 rhinos at the beginning of the twentieth century, there are only 27,000 of them left in the wild. Zara Jean Bending writes:

As Earth faces down the Holocene extinction, interdisciplinary perspectives may well be the key to challenging the status quo by producing mechanisms that are scientifically evidenced, historically informed and culturally aware.

The Tharu’s Metamorphosis

While visiting Chitwan we met Alexandre Montalto, that just finished recording this short documentary, thank you Alexandre.

Rajan Chaudhary is born Tharu. In the Nepalese lowlands they call ” Terai”, close to the Bardiya National Park, he was destined to poverty just like his brothers and sisters. Impossible for them to climb up the social ladder because of their cast, confronted to the wild creatures just like Rajan’s brother, killed and eaten by a Tiger when he was 20 years old…

In a nutshell, living just like caterpillars, eating leaves and scraps, hoping not to end up in a bird’s belly.

“But here’s the miracle: Rajan devoted his life to Tiger’s protection and became a proactive conservationist, working as correspondent for the BBC, spreading the love of nature all around the globe.

With him… and Sudip, and Ram, Ashok, Tengshu, Salik, and many others, we are offered to witness the very metamorphosis of this beautiful people, fighting against all odds”, Alexandre Montalto states.

The major conflicts are illegal extraction of park resources such as collection of firewood, fodder and timber, livestock grazing, crop raids by wild animals and loss of human life and property.

Only conservation education and adequate compensation against damages and regular monitoring of wild animals help to reduce human-wildlife conflicts.

The extents of Rhino Mythology, Folkore and Medicine in Asia are hardly to be seized here, there is still much more to discover.

~ ○ ~

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- A Rhinoceros Fighting an Elephant. https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/art/236838

- Unicorn Seal. https://web.archive.org/web/20230128042843/https://www.harappa.com/content/unicorn

- Bending Zara Jean. Improving Conservation Outcomes: Understanding Scientific, Historical and Cultural Dimensions of the Illicit Trade in Rhinoceros Horn. Macquarie University. 2019.

- Bradley Martin Esmond. Religion, royalty and rhino conservation in Nepal. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605300019487 Published online by Cambridge University Press

- Book. The Soul of the Rhino. https://books.google.com.np/books?id=AsmAtM7XPBQC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Soul+of+the+Rhino+mishra+pdf&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiNqeDJjJniAhWP6nMBHaILDKQQ6AEIIzAA#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Chapter – 7 SANCTUARING THE WILD – Shodhganga

- Chinese Unicorn The Mythic Chinese Unicorn

- Chinggis Khan and the Talking Rhinoceros of India. (Synopsis of Professor Igor de Rachewiltz’s article in Austrina, 1982) http://www.mongolianculture.com/ChinggisKhanAnd%20.htm

- Chitwan National Park.https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/284/

- Edward Pritchard Gee. The Wildlife of India.

- Elmer G. Suhr. An Interpretation of the Unicorn.An Interpretation of the Unicorn.

- Gee, E.P. 1952. The Great Indian One-Horned Rhinoceros. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 25(4): 69.

- Gee, E.P. 1964. The Wildlife of India. New York: Dullon and Co.

- https://chitwannationalpark.gov.np/

- http://www.rhinoresourcecenter.com/index.php?s=1&act=refs&CODE=s_notes&locality1=&locality2=&locality3=&locality4=&subject1=19&subject2=&taxon=6&keywords=&sort_order=desc&sort_key=r.date&st=80

- https://books.google.com.np/books?id=KnCxH85Vra4C&pg=PA277&lpg=PA277&dq=Mahabharata+rhinoceros&source=bl&ots=aY9N45ZGhV&sig=ACfU3U3FA6p1-ZGjYTC3DtuO3hy-b0QAvg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjPtYmZkpniAhUL148KHa1iCFM4ChDoATAAegQICBAB#v=onepage&q=Mahabharata%20rhinoceros&f=false

- https://britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details/collection_image_gallery.aspx?assetId=945071001&objectId=3336089&partId=1

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/605490?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- https://www.speakingtree.in/article/unicorn-tales/m-lite

- In nepal the Rhino evokes national pride. https://news.mongabay.com/2017/08/in-nepal-the-rhino-evokes-national-pride/#

- In Pragati: Evidence for the continuity between Harappan Signs and Brahmi letters.http://varnam.nationalinterest.in/2014/02/in-pragati-evidence-for-the-continuity-between-harappan-signs-and-brahmi-letters/

- Karkadann. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karkadann

- Kenoyer Jonathan Mark. Iconography of the Indus Unicorn: Origins and Legacy. https://web.archive.org/web/20211018144747/https://www.harappa.com/sites/default/files/pdf/Kenoyer2013%20Indus%20Unicorns-1.pdf

- Legend Rhino. http://www.kiplingsociety.co.uk/rg_rhino1.htm

- Mahabharata Anushasna Parva Chapter 88. https://web.archive.org/web/20210112065958/https://en.krishnakosh.org/krishna/Mahabharata_Anushasna_Parva_Chapter_88

- Mahabharata. https://books.google.com.np/books?id=56fr2p5f7l0C&pg=PA198&lpg=PA198&dq=Mahabharata+rhinoceros&source=bl&ots=HluSXaYOPJ&sig=ACfU3U3VfAs2_kVC3iRqpOSxMGXIvh_yDw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi82rvqkZniAhWJpY8KHT6nBNYQ6AEwA3oECAkQAQ#v=onepage&q=Mahabharata%20rhinoceros&f=false

- Majupuria, T.C., 1977. Sacred and symbolic animals of Nepal: animals in the art, culture, myths and legends of the Hindus and Buddhists. Kathmandu, Sahayogi Prakashan, pp. i-ii, i-vi, 1-216

- Mulmi Amish Raj. Unlocking horns. Rhino diplomacy isn’t a new phenomenon; it began as early as 1834 http://kathmandupost.ekantipur.com/news/2018-08-10/unlocking-horns.html

- McLean, J. Conservation and the impact of relocation on the Tharus of Chitwan, Nepal. Himalayan Research Bulletin. 1999.

- Parpola_A_2011_unicorn (1).pdf – Please read this

- Pashupati seal. Wiki.

- pictures: https://web.archive.org/web/20171222221656/https://www.express.co.uk/pictures/pics/3165/Rhinoceros-rhinos-critically-endangered-black-white-African-Asian-poachers-killed-horns-pictures

- Rajan Chaudhary

- Rhino horn: All myth, no medicine. Rhino horn: All myth, no medicine

- Rhino. https://web.archive.org/web/20191229072946/http://wcn.org.np:80/rhino/

- Rhino. http://www.khandro.net/animal_rhino.htm

- Rhinoceros. https://www.nature.ca/notebooks/english/indrhino_p0.htm

- Rhino resourcecenter. http://www.rhinoresourcecenter.com/index.php?s=1&act=refs&CODE=note_detail&id=1165250541

- Roman games, third to fourth century Roman floor mosaic in imperial villa at Piazza Armerina, Sicily.

- Saikia Arupjyoti. The Kaziranga National Park: Dynamics of Social and Political History. Conservation and Society 7(2): 113-129. 2009. http://www.conservationandsociety.org

- Sharples Tiffany. A Brief History of the Unicorn.2008. http://content.time.com/time/health/article/0,8599,1814227,00.html

- Supplement to the Rishyashringa article [Search domain mahabharata-resources.org/ola/rishya_sup.html] mahabharata-resources.org/ola/rishya_sup.html

- The Unicorn. https://web.archive.org/web/20230128042843/https://www.harappa.com/content/unicorn

- Unicorn Seal, Mohenjo-daro. https://web.archive.org/web/20230606223413/https://www.harappa.com/indus/25.html

- Unicorn- fantastically wrong. https://www.wired.com/2015/02/fantastically-wrong-unicorn/

- Unicorn. https://www.britannica.com/topic/unicorn

- Unicorn. https://www.britannica.com/topic/unicorn

- Unicorns in Peril. https://web.archive.org/web/20200322223243/http://nopr.niscair.res.in/bitstream/123456789/30762/1/SR%2052%283%29%2034-35.pdf

- Unlocking horns. http://kathmandupost.ekantipur.com/news/2018-08-10/unlocking-horns.html

- Vajrachary Gautama V. Unicorns in Ancient India and Vedic Ritual. https://web.archive.org/web/20230928141017/http://www.ejvs.laurasianacademy.com/Unicorn-compressed.pdf

- https://elibrary.tucl.edu.np/JQ99OgQIizUxyjI9nB0on9OyLkqsGIf4/api/core/bitstreams/f8d87e7e-be32-4d8e-8093-cb9278b25e45/content

Keep exploring: