Tiger cults: How local beliefs and practices shape human-wildlife coexistence in rural India

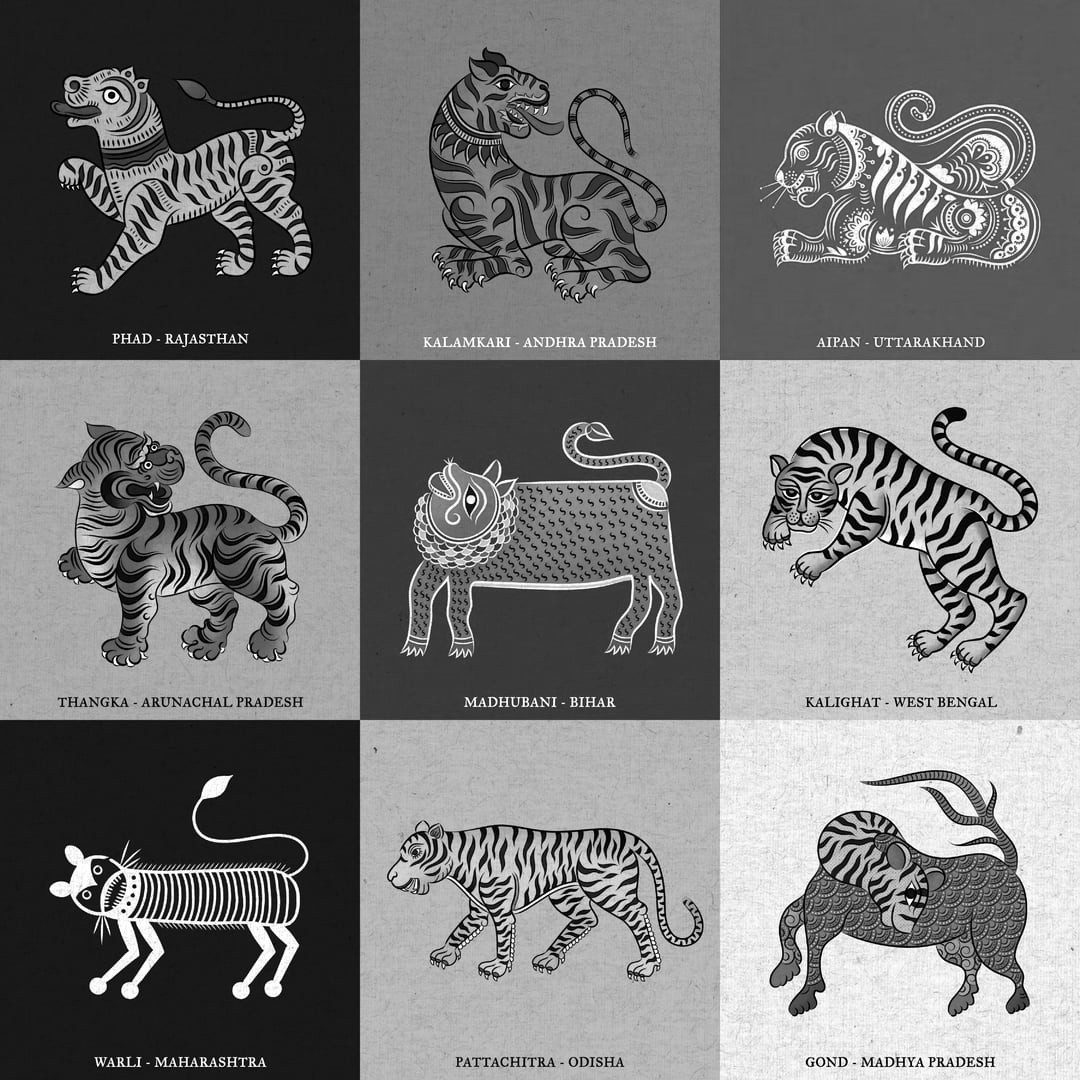

The sacred and dangerous Tiger is deeply rooted in the beliefs, myths and history of the Indian sub-continent. All over its habitat, the Bengal Tiger and shades of its existence can be seen finely woven with the local culture and tradition.

Were-tigers, tigerman, tiger goddesses and tiger gods, local beliefs and practices shape human-wildlife coexistence in India. Because communities that share space with tigers view the striped animals as “beasts”, “protectors”, “owners”, “family” or as “vehicles of the gods”. The tribal tiger takes different shapes that echo through India’s forests out of fear and hope.

In this Article

Scheduled Tribes in India

In India, there are 705 ethnic groups living across 20 states, of estimated 104 million or 8.6% of the national population. This people are officially recognized as “Scheduled Tribes” in the Constitution, Article 366 (25) and Article 342. There are many more ethnic groups that are not officially recognized, therefore, the total number of the tribal population is higher than the official figure.

Interconnections of Tribal Terminology in India. MaxA-Matrix. Public domain,edited.

The Scheduled Tribes are usually referred to as Adivasis, which literally means Indigenous Peoples or original inhabitants. The term was coined in the 1930s and is derived from the Hindi word “adi” which means “of earliest times” or “from the beginning” and “vasi” meaning inhabitant or resident.

They possess distinct identities and cultures linked to certain territories, often forests, that is why they are also called Forest tribes or Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (OTFD).

Tigers and other wildlife are intertwined with faith, folklore and myths of Adivasis.

Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups

There are certain Scheduled Tribes, 75 in number known as Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs) of India:

| State / UT Name | PVTGs Name |

| Andhra Pradesh and Telangana | 1. Bodo Gadaba 2. Bondo Poroja 3. Chenchu 4. Dongria Khond 5. Gutob Gadaba 6. Khond Poroja 7. Kolam 8. Kondareddis 9. Konda Savaras 10. Kutia Khond 11. Parengi Poroja l2. Thoti |

| Bihar and Jharkhand | 13. Asurs 14. Birhor 15. Birjia 16. Hill Kharia 17. Konvas 18. Mal Paharia 19. Parhaiyas 20. Sauda Paharia 21. Savar |

| Jharkhand | Same as above |

| Gujarat | 22. Kathodi 23. Kohvalia 24. Padhar 25. Siddi 26. Kolgha |

| Karnataka | 27. Jenu Kuruba 28. Koraga |

| Kerala | 29. Cholanaikayan (a section of Kattunaickans) 30. Kadar 31. Kattunayakan 32. Kurumbas 33. Koraga |

| Madhya Pradesh | 34. Abujh Macias 35. Baigas 36. Bharias 37. Hill Korbas 38. Kamars 39. Saharias 40. Birhor |

| Chhattisgarh | Same as above |

| Maharashtra | 41. Katkaria (Kathodia) 42. Kolam 43. Maria Gond |

| Manipur | 44. Marram Nagas |

| Odisha | 45. Birhor 46. Bondo 47. Didayi 48. Dongria-Khond 49. Juangs 50. Kharias 51. Kutia Kondh 52. Lanjia Sauras 53. Lodhas 54. Mankidias 55. Paudi Bhuyans 56. Soura 57. Chuktia Bhunjia |

| Rajasthan | 58. Seharias |

| Tamil Nadu | 59. Kattu Nayakans 60. Kotas 61. Kurumbas 62. Irulas 63. Paniyans 64. Todas |

| Tripura | 65. Reangs |

| Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand | 66. Buxas 67. Rajis |

| West Bengal | 68. Birhor 69. Lodhas 70. Totos |

| Andaman & Nicobar Islands | 71. Great Andamanese 72. Jarawas 73. Onges 74. Sentinelese 75. Shorn Pens |

Tribes in India have their own traditions, cultural heritage and folklore. The life and economy of the tribal people are intimately connected with the forests (living in and around forested areas).

They may rely on forests for a variety of purposes, including hunting and gathering, agriculture, pastoralism, and non-timber forest products such as honey, medicinal plants, and bamboo.

Forest dwellers are classified into Primitive tribes, Nomadic tribes and Semi-nomadic tribes. The Forest Rights Act (FRA), 2006 recognizes the rights of the forest-dwelling tribal communities and other traditional forest dwellers to forest resources for various needs, including livelihood, health ( medicinal plants), habitation, and other socio-cultural needs. Their religion and folklore are woven round the spirits of the forest.

The impact of the Forest Rights Act, 2006, on forest dwellers’ rights in India can be assessed in several ways:

Recognition of Rights:

- The FRA recognizes the rights of forest-dwelling communities over traditional forest lands, including both individual and community rights.

- It acknowledges their historical rights to access, use, and manage forest resources.

Land Titles and Ownership:

- Forest dwellers can apply for individual and community titles for the land they have been traditionally occupying.

- This helps in securing land tenure and ownership rights, which is crucial for the socio-economic development of these communities.

Cultural and Livelihood Rights:

- The Act recognizes the cultural and livelihood rights of forest-dwelling communities, allowing them to continue their traditional practices of agriculture, grazing, and collection of minor forest produce.

- This helps in preserving the traditional way of life and sustainable use of forest resources.

Conservation and Sustainable Management:

- FRA emphasizes the role of forest-dwelling communities in the conservation and sustainable management of forests.

- By involving local communities in decision-making processes, the Act aims to strike a balance between conservation and the livelihood needs of the people.

Social Empowerment:

- The Act is seen as a tool for social empowerment as it gives marginalized communities a legal framework to assert their rights over forest resources.

- It addresses historical injustices and discrimination faced by these communities.

Challenges and Implementation Issues:

- Despite its positive intent, the implementation of the FRA has faced challenges, including lack of awareness, bureaucratic hurdles, and opposition from certain quarters.

- Ensuring that the intended benefits reach the grassroots level remains a significant challenge.

Environmental Concerns:

- Critics argue that the Act might lead to over-exploitation of forest resources as local communities gain more control. Striking a balance between community rights and conservation is an ongoing challenge.

The Forest Rights Act in India represents a significant step towards recognizing the rights of forest dwellers and addressing historical injustices. However, the effective implementation of the Act, along with addressing associated challenges, remains crucial for achieving its intended goals and ensuring a harmonious relationship between forest conservation and the rights of local communities.

Map: Human – tiger coexistence in India

The map shows most of the tribal populations (adivasis) and cultures of the Indian subcontinent within the different states of India and where tiger-human coexistence takes place.

The largest concentrations of Indigenous Peoples are found in the seven northeastern states of India, and the so-called “central tribal belt” that stretches from Rajasthan to West Bengal.

Tiger distribution range in India

The Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris) distribution range is shown where tiger-human coexistence happens:

- Shivalik Hills, Gangatic Plains (Shivalik hills, the Bhabhar tract and the Terai plains – Nepal and India) It traverses across the political boundaries of Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, and Bihar) ,

- The Brahmaputra flood plains (and Upper Bengal Dooars) and

- the Northeastern Hills (Sikkim and the Seven Sisters of India – Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Meghalaya, Manipur, Mizoram, Nagaland, and Tripura).

- The Sundarbans (the world’s largest mangrove forest located at the estuarine phase of Ganges and Brahmaputra river system spreading across Bangladesh and West Bengal, East India).

- Central India highlands into the Eastern Ghats ( a range of mountains along India’s eastern coast. It traverses across the political boundaries of Andhra Pradesh, Chattisgarh, Jharkhand, Maharastra, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha and Rajasthan).

- The Deccan Plateau is bounded on the east and west by the Ghats:

- the Eastern Ghats ( south of Andhra Pradesh) and

- the Western Ghats (Sahyadri), a range of mountains along the western coast of the Indian peninsula. This landscape traverses across the political boundaries of Goa, Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

So far, 58 Tiger Reserves have been established in India.

State-wise list of 58 Tiger Reserves in India 2025

| S.No | State | Tiger Reserves Names |

| 1 | Andhra Pradesh | Nagarjuna Sagar Srisailam |

| 2 | Arunachal Pradesh | Namdapha |

| 3 | Pakke | |

| 4 | Kamlang | |

| 5 | Assam | Manas |

| 6 | Nameri | |

| 7 | Kaziranga | |

| 8 | Orang | |

| 9 | Bihar | Valmiki |

| 10 | Chhattisgarh | Udanti-Sitanadi |

| 11 | Achanakmar | |

| 12 | Indravati | |

| 13 | Guru Ghasidas – Tamor Pingla | |

| 14 | Jharkhand | Palamau |

| 15 | Karnataka | Bandipur |

| 16 | Bhadra | |

| 17 | Dandeli-Anshi (Kali) | |

| 18 | Nagarahole | |

| 19 | Biligiri Rangaswamy Temple | |

| 20 | Kerala | Periyar |

| 21 | Parambikulam | |

| 22 | Madhya Pradesh | Kanha |

| 23 | Pench | |

| 24 | Bandhavgarh | |

| 25 | Panna | |

| 26 | Satpura | |

| 27 | Sanjay-Dubri | |

| 28 | Veerangana Durgavati | |

| 29 | Ratapani | |

| 30 | Madhav | |

| 31 | Maharashtra | Melghat |

| 32 | Tadoba-Andhari | |

| 33 | Pench | |

| 34 | Sahyadri | |

| 35 | Navegaon-Nagzira | |

| 36 | Bor | |

| 37 | Mizoram | Dampa |

| 38 | Odisha | Similipal |

| 39 | Satkosia | |

| 40 | Rajasthan | Ranthambore |

| 41 | Sariska | |

| 42 | Mukundra Hills | |

| 43 | Ramgarh Vishdhari | |

| 44 | Dholpur – Karauli Tiger Reserve | |

| 45 | Tamil Nadu | Kalakad- Mundanthurai |

| 46 | Mudumalai | |

| 47 | Sathyamangalam | |

| 48 | Anamalai | |

| 49 | Srivilliputhur- Megamalai | |

| 50 | Telangana | Kawal |

| 51 | Amrabad | |

| 52 | Uttar Pradesh | Dudhwa |

| 53 | Pilibhit | |

| 54 | Ranipur | |

| 55 | Uttarakhand | Corbett |

| 56 | Rajaji | |

| 57 | West Bengal | Sunderbans |

| 58 | Buxa |

Tiger – human coexistence in India

India’s tiger conservation strategy combines two approaches:

some areas are strictly protected reserves (core area or critical tiger habitats) , while others are multi-use landscapes (buffer zones) where tigers and local communities, Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers, share space.

An adult Bengal tiger typically has a home range of 40–150 sq.km., depending on factors such as sex and location.

The core area usually has a legal status of National Park or Wildlife Sanctuary. It is the critical habitat of tigers, co-predators and prey animals with favorable ecological conditions to ensure long-term success of the species.

No human activity save for conservation-related or park-management related activities are permitted in the core area. Everyday tasks of wood collection, grazing and utilization of forest produce is banned.

Tourism is permitted, however according to the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) guidelines, only up to 20% is available for Wildlife Tourism.

Further, adjoining or surrounding areas, give also habitat for the wildlife, which inevitably spills over from the declared core zone. This ecologically sensitive zone (buffer, coexistence area, multiple-use area) is required around the core zone for sustaining tigers mature enough to create their own space and old displaced tigers.

Ongoing village Relocation Programs in Tiger Reserves

The success story of the tiger is not one of wilderness untouched – it’s a tale of complex coexistence with humans. At the heart of this are the Voluntary relocation of people and settlements in and around Tiger Reserves across India, to reduce poaching threats and for habitat preservation.

The relocation process goes on since 1973.

Compensatory land or money is provided as aid from the government along with logistical assistance for improved accommodations, farm land, employment (cultural tourism, forest guards), health, and education services. (Revised Guidelines for the Ongoing Centrally Sponsored Scheme of Project Tiger, 2008′ and subsequent additional guidelines)

Voluntary relocation is not any more, now, C.R. Bijoy explains:

More than 89,800 families from 848 villages, mostly belonging to the Adivasi community that is entitled to forest rights, are to be summarily relocated from Critical Tiger Habitats (CTHs) or the core area of 54 tiger reserves. The exact number of people residing in the core area is as yet unknown.

The National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) directed all 19 tiger-bearing states on June 19, 2024 to relocate them on a ‘priority basis’, calling for action plans and regular progress reports.

Nearly 2.5 lakh (250000) of the 4 lakh (400000) now scheduled for relocation are from the central Indian tribal belt of Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Maharashtra and Chhattisgarh. (2022-23 for rural areas)

The challenge of Human Rights, Political pressure and vested interest groups remains.

The Tribal Protector – The tiger is worshiped as a god.

The tiger commands fear and respect across different regions and cultures of Asia.

Traveling across India and Nepal we have been told stories and anecdotes about the beast – both inspiring and terrifying.

We saw marks and stitches from attacks and shrines for lost family members.

Although there is an element of fear associated with the big cat, for most animist communities, there is also trust in the big cat as a protector. An example of this can be seen in the story of a little boy who was once looked after by a leopard.

The little boy fell asleep at a Tiger-god shrine during a ritual and was forgotten there. When his family went back to fetch him they found a big cat sitting guard over the sleeping child. Once villagers approached the shrine, the predator went away, having done no harm.

It is believed that the leopard kept watch over the boy, because it knew that the people worship him.

Such narratives, both of the past and present reinforce the belief among people that their faith in the carnivore-god is what keeps them safe.

Adivasis are the “first inhabitants” of India who mostly live in remote, difficult to reach regions of the country. Given that tribes in the country live in or close to forested areas, it is only natural that the tiger features strongly in their folklore.

Where the most tigers survive today is due to the numerous sacrifices made by the villagers agreeing to relocate from their established homes in the various Tiger Reserves at the behest of the Indian Government.

Safety operating protocol for staying safe in tigerland

SOP to keep people safe from potential conflicts with tigers, example from the Deccan 2024 -Telangana.

- Avoid forest routes;

- Use whistles and drums when you move (we have often noticed local people playing loud music on the cellphone when moving in the jungle)

- Move in groups of 8 to 10 people; two from the group should be deployed as sentries

- Wear face masks on the back of the head while out in the field;

- Farmers guarding crops must stay on machans in their fields;

- Those grazing animals, must stay within a half km radius of their villages;

- grazing between 10 am, and 4 pm;

- Carry a stick with a bell attached to it while going to the field;

No one should do any action that can harm tigers, such actions will face action under Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972.

Form village protection committees, with a forest officer and one police officer to be nominated by the local sub-inspector;

Report any evidence of tiger presence to the committee; Inform committee while leaving the village, and the route

Drones with cameras, camera traps are also being employed to track the tiger’s movement to keep people safe, and to prevent any further human tiger interactions.

Not all tribes revere the tiger, in the East of India, diverse communities traditionally hunt big cats like tigers and leopards, ritually as well as for protection and economic gain.

Tiger cults of Central India

Worship of the tiger god under different names is prevalent in many tribes of India.

Indian tree spirits, says Mr. Crookes in his Popular Religion of Northern India, these tree ghosts are very numerous. Local shrines are constructed under trees ; and in one particular tree, the Bira, the jungle tribes of Mirzapur locate Bagheswar, the tiger god, one of their most dreaded deities.

In the Central Provinces of India, a favorite household deity is Dulha Deo, the spirit of a young bridegroom who was carried off by a tiger on his way to his wedding.

When a marriage is celebrated, a miniature coat, a pair of shoes, and a bridal crown are offered to Dulha Deo, and sometimes also the model of a swing on which the child may amuse himself. Inside the house Dulha Deo is represented by a date and a nut tied up in a small piece of cloth and hung on a peg in the wall.

When worship is to be performed, the date and nut are taken down and set on a platform, and offerings of food and other articles are laid before the deity on leaf plates. On the occasion of a marriage, or the birth of a first child, or in every third year, a goat is offered to Dulha Deo.

Baghadeva of the Warli tribes

The Warli tribes live in the North of Mumbai in Maharashtra on tracts of land along the Gujarat border. They worship the tiger as a symbol of fertility and is believed to bring a good harvest. Rituals involve the worship of trees, stones, rivers and statues of tigers surrounded by flowers, birds, and snakes.

They practiced subsistence agriculture using the slash and burn method, and rarely used fertilizers, hence believing that Mother Earth had her own method of fertilizing herself and man-made fertilizers would do harm to it.

Wagle is a totemic family name, while Waghmare is a family name once borne as a title of a tiger killer.

Waghya is the god of the Warli tribe, represented as a shapeless stone. He is also the main deity of the Dhangar, Bapujipoa (Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh) and Rathwa of the Kolis (some say Bhil peopele) across central-west India (Gujarat, Maharashtra).

This tribes belief, that the tiger will bring rainfall to the farmers in need and any insult to the tiger will result in a drought, making it a powerful symbol of fertility.

Some believe, so Hastings James, 1912, that spirits rob the grain till it is measured, thinking they cannot be found out, but when once it has been measured they are afraid of detection. It is considered unlucky for any one who has ridden on an elephant to enter the threshing-floor, but a person who has ridden on a tiger brings luck.

Consequently the forest Gonds and Baigas, if they capture a young tiger and tame it, will take it round the ‘country, and the cultivators pay them a little to give their children a ride on it.

Phallic-shaped wooden and stone images were daubed in red to indicate their extreme sanctity and were placed as symbols of fertility, not only for the crop fields but also for marriages and the birth of children.

In Baroda, at the worship of Vagli Deo, the tiger-god, a man is covered with a blanket, bows to the image, and walks round it seven times.

During this performance the worshipers slap him on the back. He then tries to escape to the forest, pursued by the children, who fling balls of clay at him, and finally bring him back, the rite ending with feasting and drinking.

Warli paintings are indicative of the deep links of the tribals with the tigers. In this way, the tiger also signified a vital link between diverse cultures and the magic of the tiger determines the relationship between man and tiger in many parts of tribal India.

In Warli paintings the tiger is depicted as a warm and friendly animal sitting or passing through the village. Warlis have always had faith in their tiger god Baghadeva.

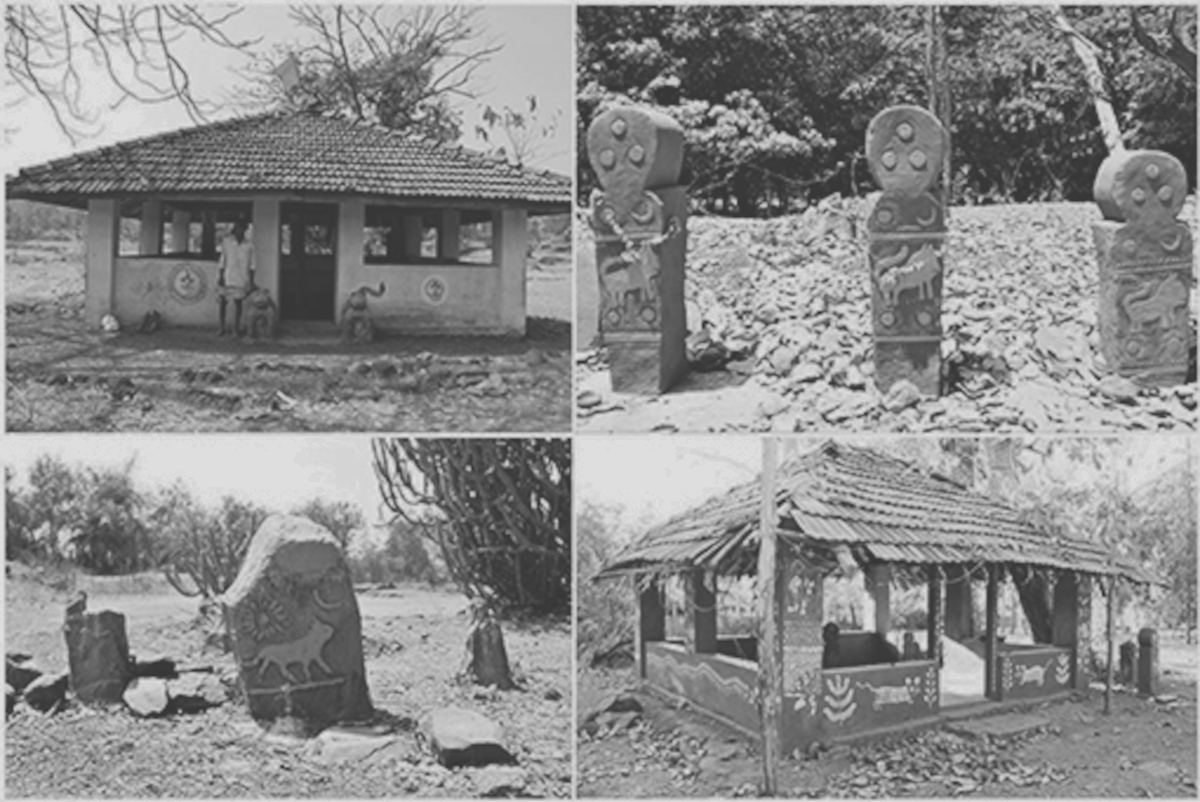

Carved wooden statues of tigers with the sun, moon and the milky-way in the background can be seen all over their habitat.

Warlis believe that the tiger is supreme to all other organisms and that the universe exists only because of the tiger.

They are known to commence important life and social events such as weddings, naming a child and building new homes only after receiving blessings from Waghoba.

On how Waghoba shrines came to be

The ethnographic fieldwork of Nair R, Dhee, Patil O, Surve N, Andheria A, Linnell JDC and Athreya V, in: Sharing Spaces and Entanglements With Big Cats: The Warli and Their Waghoba in Maharashtra, India. 2021, shed light on the origin of waghoba shrines:

“While there is no single origin story of this deity, we came across multiple parallel narratives that describe myths or instances that gave birth to the deity. Stitching together fragments of stories from different interviews, the authors learnt of the origin stories that narrate how the deity came into being.

These narratives illustrate a woman, typically a princess or chief ’s daughter, who gives birth to a baby out of wedlock. When his mother is out doing chores, the baby shape-shifts into a tiger and hunts the villager’s livestock.

Troubled and scared by the tiger, the villagers decide to kill the tiger. To save her child, the mother mediates between the angry villagers and her baby. In the negotiation that follows, she asks her child to go away into the forest and in exchange, the people would install shrines for the wagh, and once a year give an offering of the animals he likes (such as chickens and goats) to make peace.

That is the story of how the wagh then took sanctuary in the forest and Waghoba shrines came to be established across all villages.”

The festival of Waghbaras which literally translates to wagh-festival is observed annually, for two days, to appease Waghoba (on the first day of the Hindu festival of Diwali based on the lunar calendar). The festival entails celebrations, rituals and traditions to appease Waghoba at the local shrine.

People offers a variety of things as per their ability, from flowers, coconuts, and incense to toddy (fermented palm drink), chickens and goats. The heads of the sacrificed animals are kept at the shrine and the rest of the meat is distributed among people.

The idols are also smeared with vermilion paste, which is considered auspicious. Orally passed down chants and songs dedicated to Waghoba are presented throughout the festival days and nights.

During worship rituals, the bhagat, the local equivalent of a shaman, is believed to take the form of a wagh by entering into a state of trance. Shamans are also sometimes believed to be capable of retrieving medicinal plants from the mountains in this tiger- state and to have a strong intuition or may prophesize.

Bagheshwar or Bagesur Dev of the Baiga tribes

The Baiga ethnic group found in the forested heart of India primarily lives in Madhya Pradesh, and in smaller numbers in the surrounding states of Uttar Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand.

They worship Bagheshwar or Bagesur Dev and consider the tiger their spiritual brother and protector of the forest.

They conduct elaborate ceremonies to seek the tiger’s blessings for their crops and safety.

Were-tigers are magical shape shifters – who attack people:

The modern English compound term weretiger (also spelt as were-tiger, wer-tiger) is formed by the union of the Old English word wer- ‘man’ and the word ‘tiger’ on the analogy of the term werewolf.

Therianthropy, derived from the Greek thērion (meaning ‘wild beast’) and anthr ōpos (meaning ‘human being’), is the general category of shape-shifting in which man or woman is able to transform into animal and back.

In Asia, the southern regions of China, India, Nepal and Indonesia the tiger (or, alternatively, the leopard), the most formidable wild carnivorous mammal, is the most common form assumed by alleged shape-shifters. Francesco Brighenti, in: Kradi Mliva, explains.

In 1957, Arthur N. W.Powell, reported a version of the irreversible transformation yarn told to him by two old shikari friends in Balaghat, one a Baiga, the other a Gond. To slay a real man-eater of the neighborhood, they said, a banyan, or moneylender, transformed himself into a tiger by swallowing a powder given to him by a sadhu for the task.

Sadly he entrusted the antidote to his pretty young wife. After killing and eating her, he became “the

most dreaded man-eater in human memory,” claiming thousands of lives. (Newman, Patrick, 1961–

Tracking the weretiger : supernatural man-eaters of India, China and Southeast Asia. 2012.)

How a Baiga priest lays the ghosts of men who have been killed by tigers, and so checks the ravages of the ferocious animals

In the country where the Baigas dwell they are regarded as the most ancient inhabitants and accordingly they usually act as priests of the indigenous gods.

Certainly there is reason to believe that in this part of the hills they are predecessors of the Gonds, towards whom they occupy a position of acknowledged superiority, refusing to eat with them and lending them their priests or enchanters for the performance of those rites which the Gonds, as newcomers, could not properly celebrate.

Among these rites the most dangerous is that of laying the ghost of a man who has been killed by a tiger.

Man-eating tigers have always been numerous in Mandla, the breed being fostered by the large herds of cattle which pasture in the country during a part of the year, while the withdrawal of the herds for another part of the year, to regions where the tigers cannot follow them, instigates the hungry brutes to pounce from their covers in the tall grass on passing men and women.

When such an event has taken place with fatal results, the Baiga priest or enchanter proceeds to the scene of the catastrophe, provided with articles, such as fowls and rice, which are to be offered to the ghost of the deceased.

Arrived at the spot, he makes a small cone out of the blood-stained earth to represent either the dead man or one of his living relatives.

His companions having retired a few paces, the priest drops on his hands and knees, and in that posture performs a series of antics which are supposed to represent the tiger in the act of destroying the man, while at the same time he seizes the lump of blood-stained earth in his teeth.

One of the party then runs up and taps him on the back. This perhaps means that the tiger is killed or otherwise rendered harmless, for the priest at once lets the mud cone fall into the hands of one of the party. It is then placed in an ant-hill and a pig is sacrificed over it.

Next day a small chicken is taken to the place, and after a mark, supposed to be the dead man’s name, has been made on the fowl’s head with red ochre, it is thrown back into the forest, while the priest cries out

“Take this and go home.”

The ceremony is thought to lay the dead man’s ghost, and at the same time to keep the tiger from doing any more harm.

For the Baigas believe that if the ghost were not charmed to rest, it would ride on the tiger’s head and incite him to fresh deeds of blood, guarding him at the same time from the attacks of human foes by his preternatural watchfulness. (Captain J. Forsyth, The Highlands of Central India. 1871.)

Olthwa – Tigerman – tigerspirits

Tribal groups inhabiting the Maikal Hills in Chhattisgarh, primarily of Gond and Baiga ethnicity, believe in the existence of tigermen, referred to as olthwa, who are often identified with the spirits of evil men who died due to tiger attacks, and therefore could not attain peace in the realm of ancestors. Tigers possessed by an olthwa spirit are distinguished by their craving for human blood; they do not kill their victims, merely wounding them to drink their blood.

The tribals consider themselves descendants of the Tiger and maintain a form of respect towards the animal. They believed their ancestors’ spirits dwelt in the tiger. It is also invoked as a guardian of their crops against deer/boar foraging – a balancer of herbivore numbers and dispatched to the tribals relief by Mother Nature herself.

Though many of the younger generation would not have seen the tiger, it is present in Baiga art.

In March 2022, Jodhaiya Bai received the Nari Shakti Puraskar for women’s empowerment and was then awarded the Padma Shri in March 2023, the highest civilian honor for cultural and artistic achievement by the President of India.

Bagheshwar of the Bharia tribes

The Bharias from Madhya Pradesh, believe in Bagheshwar or Bagheshur – the tiger god. The name combines “Bagh” (tiger) and “Ishwar” (god) in Hindi. Because of Bagheshwar’s protection, no Bharia will be eaten by a tiger. During Diwali, they place a bowl of gruel behind their houses for the tiger. In the morning, an empty bowl signifies that the house has been visited by Bageshwar.

Bagh Deo or Waghoba of the Gond tribes

The Gondi people are spread over the states of Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Uttar Pradesh, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, and Odisha. They worship a tiger god named Bagh Deo or Waghoba, who is considered the savior and protector of his devotees.

There is a tiger or Bagh clan, the members of which consider themselves descendants of the fearful predator. Waghoba worship is not just a religious ritual; it is a deeply personal practice shaped by individual experiences of loss and reverence.

A person who has been killed by a tiger or a cobra may receive a general veneration with the object of appeasing his spirit and transforming him into a village god.

In Chandrapur, Ashraf Shaikh explains: it is common to find Waghoba shrines erected at spots where a tiger killed a person – serving as a memorial and protective measure.

The Govari community adds a unique dimension to this practice.

When a tiger kills a woman, a statue of Waghin or Waghaai, the female equivalent of Waghoba, is installed at the attack site. Offerings are, typical for goddesses, like woman’s attire, such as a saree and a mangalsutra (wedding necklace).

If a tiger makes trouble, a stone is set up in his honor, and he receives a small offering.

If a Gond, when starting a journey in the morning, should meet a tiger, he should return and postpone his journey. But if he meets a tiger during the journey, it is considered good luck.

Gonds think they can attain strength by carrying tigers’ shoulder bones on their shoulders or by drinking the dust of tigers’ bones pounded in water.” (R.V. Russell. Tribes and castes of the Central Provinces of India).

The tiger is revered in the Sarwen Saga, and it is regarded as a relative.

Garima Malik and Sabina Sethi

Gond weretiger-lore

Gond tales about tiger-transformation describe the metamorphosis from man to tiger in terms of physical shape-shifting and as a supernatural ability which can only be manifested by an act of profane – that is, non-religious – magic.

In some such stories, for example, a man rubs his back in a particular manner against a white ant-hill and is then magically turned into a tiger on the spot; in other cases, he eats a certain root or alternatively sniffs, or else rubs on his body, a certain drug prepared with some medicinal plants, roots, etc. and is then magically converted into a tiger on the spot.

There is always some kind of a material medium enabling the shape-shifter to get physically transformed into a feline. In this connection, it cannot be excluded that beliefs in the efficacy of some as yet undetermined form of Tantric magic may in the past have contributed to the shaping of both the Munda and Gond weretiger-lore. Francesco Brighenti, in: Kradi Mliva, explains.

We occasionally find among the northern tribes the habit of tearing the victim in pieces, as in the Gond sacrifice to Bagheshvar, the tiger-god.

The nuptial, funeral, and similar ceremonies are performed under the lead of aged relations. But generally in every village there is a man who is supposed to have the power of charming tigers and preventing by spells (mantra) such calamities as drought, cholera, etc. He is called a Baiga. (Hastings James. 1912.)

The boṅga – tigerspirt of the Munda

In the late 19th century the Munda and the Ho tribes people believed that certain men, initiated into the cult of specific divine spirits (boṅga) of a malign nature, could physically turn into tigers or other prey animals.

These men, considered powerful sorcerers, were pointed out as a danger to the entire community and were sometimes killed, without any form of trial, by the relatives of those who had fallen victim to a tiger ambush.

It was believed that these individuals could devour entire domestic animals during the night, roaring like tigers. (E.T. Dalton, Descriptive Ethnography of Bengal [reprint, Calcutta: Firma K.L. Mukhopadhyaya, 1960]).

Among the Mundas of the Chhotanagpur Plateau the spirits of tiger victims are called baghaia boṅga. Such unpacified spirits, the Mundas assert, compel the animals that ended their earthly existence to attack other humans, or else they roam in groups in the jungle, hunting humans using tigers as hounds.

The baghia – tigerspirts of the Kharias

The Kharias refer to the spirit of an individual killed by a tiger as baghia, who, after the destruction of his or her body, has succeeded in gaining control over the animal that attacked him or her. The tigers thus controlled tend to attack humans and domestic animals. Tiger spirits can be appeased and driven away through community or family rituals. Roy and R.C. Roy, The Kharias (Ranchi: Man in India Office, 1937)

Gond man – eater lore

Colonial literature reported incidents of were-tigers turned man-eaters from 1931. L. A. Cammiade drives from ” The Terror of Danauli,” by Leonard Handley, where he describes how, in the Central Provinces, he tracked down and shot at close quarters a man-eater that had killed over thirty people.

No whisper seems to have reached Mr. Handley’s ears that the man-eater he was hunting was not really a tiger, but a man who by magic had assumed that form for nefarious ends. That such, indeed, was the firm opinion of the local jungle people, the Gonds, is evident from several of the details recorded by Mr. Handley.

“These figures are said to be tiger deities, who had to be propitiated after the slaying of the man-eater.” […]

The ceremony that was performed at the feet of the deities shown in the illustration savors more of an act of thanksgiving for deliverance from the ravages of the man-eater.

The purely human shape of the figures and their peaceful attitude do not indicate blood-thirsty gods, but strongly remind me of the statues set up by modem Koi to the spirits of notable ancestors. […] Filial prayer is offered at these memorial stones to the spirits of the ancestors. The usual prayer of one of these semi-savage jungle people [sic] was, in the suppliant’s own words,to the following effect:

” I am starting on my journey through the forest to the weekly market. You are my ancestors, and I am your child. You must see that I get a good price for the tamarind I am selling, and you must protect

L. A. Cammiade. Man-Eaters and Were-Tigers. In the Illustrated London News, 30th May, 1931, pp. 928-29.

“me from the tiger on the way.”

Gond sacrifices for tiger protection

Among the Gonds of the Central Provinces in India the sun, or, as they call him, Narayan Deo, is a household deity, he has a little platform inside the threshold of the house; says Frazer, 1919, and continues:

He may be worshipped every two or three years, but if a snake appars in the house, or any one falls ill, they think Narayan Deo is impatient and perform his worship.

A young pig is offered to him and is sometimes fattened up beforehand by feeding it on rice. The pig is laid on its back over the threshold of the door, and a number of men press a heavy beam of wood on its body till it is crushed to death.

They cut off the tail and testicles, and bury them near the threshold.

The body of the pig is washed in a hole dug in the yard, and it is then cooked and eaten.

They sing to the god:

Eat, Narayan Deo, eat this rice and meat, and protect us from all tigers, snakes and bears in our houses protect us from all illnesses and troubles.’

Next day bones and any other remains of the pig are buried in the hole in the compound.

There is a cultural link with some tribes of Northeastern India, namely, the Garos and Khasis of Meghalaya and the Nagas of Nagaland. Indeed, the Garos and Nagas (both speaking Tibeto-Burman languages) and the Khasis (Austroasiatic speakers) each possess a rich weretiger-complex having many aspects in common with that of the Kondhs, chief among which is the notion of a migration of the human soul into the body of a tiger or leopard occurring during sleep

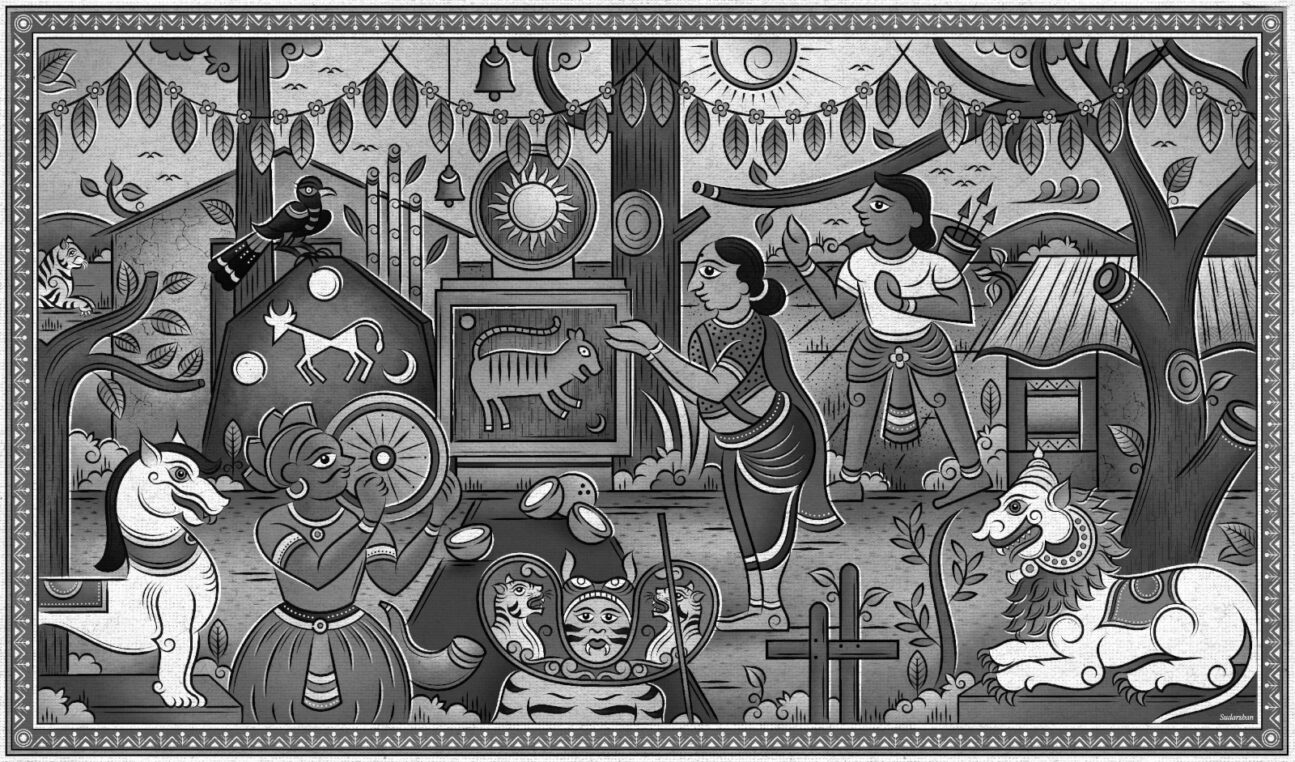

Tiger in Gond paintings

The tradition of Gond painting evolved from ritual storytelling, accompanied by decorating the walls to commemorate special occasions and bring good luck and protection from evil.

Since the Gond artists themselves believe that portraying various deities and scenes from mythology and looking at them brings good luck, particular attention is often given to portraying the tiger, for it is considered among the strongest and most powerful animals in the jungle.

Subhash Vyam’s work Tiger and Aeroplane shows a tiger, cow and birds gazing up at an aeroplane passing overhead in the sky. This is where modern times meet local culture and history.

Bana Dev of the Gond tribe

Artist – Naresh Shyam

In this painting, the painter depicts Tiger Bana Dev who is always ready to protect the devotees. Whenever there is a quarrel between the husband and a wife in the house and the wife tries to escape, the Tiger Dev hides in the street and frightens her and sends the wife back. Sajha tree leaves are also used in marriage. (CC-BY-4.0, edited.)

Chitan Deo of the Muria tribe

The Murias are an Adivasi, scheduled tribe Dravidian community of the Bastar district of Chhattisgarh, India and are part of the Gondi people. They worship Chitan Deo, who is a hunting tiger god for them.

The Tiger deity of Bheels and Bhilalas

Kathotiya’s tribals of Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, mostly consist of Bheels and Bhilalas – R.V. Russell explains – Kathotia, a group named after a Kathota (a bowl), reveres the tiger god whose idol resides on a little platform on the veranda.

Its members may not join a tiger beat and will not sit up for a tiger over a kill. In the latter case, they believe that the tiger will not come and will be deprived of its food if they do so and all their family members will fall ill.

If a tiger takes away one of their cattle, they think there has been some neglect in their worship of him.

They say that if one meets a tiger in the forest, he should fold his hands and bow down and say

“Maharaj, let me pass”

and the tiger will walk away.

If a tiger is killed within the limits of the village, a Kathotia Kol will throw away all his earthen pots in mourning and shave his head and feed a few men of his sept.”

Some Bhil tribal groups in Gujarat worship a tiger-god named Wagh Dew, believed to reside in the jungle-covered hills. Associated with a feline manifestation of Śhiva, he is primarily invoked for protection against attacks from ferocious beasts.

Witch-tigers

Spence Lewis,1920, writes:

We find witchcraft most prevalent among the more isolated and least advanced races[sic], like the Kola, Bhils, and Santals.

Witches also take animal forms, especially those of tigers and stories of trials are related at which natives gave evidence that they had tracked certain tigers to their lairs, which upon entering they had found tenanted by a a notorious witch or wizard. For such witch-tigers the usual remedy is to knock out their teeth to prevent their doing any more mischief.

Strangely enough the Indian witch… is very often accompanied by a cat. The cat, say the jungle people, is aunt to the tiger, and taught him everything but how to climb a tree. Zalim Sinn, the famous regent of Kota, believed that cats were associated with witches, and imagining himself enchanted ordered that every cat should be expelled from his province.

The Idu Mishmis have declared parts of their forest land as “Community Conserved Areas” and govern it by them selves. The Bishnoi Tiger Force, is an environmental campaign group, that actively fights against poaching and rescues injured animals in Rajasthan.

Tiger cults of West India

In western India the people had a deep belief that the large cat; a leopard Panthera pardus or a tiger Panthera tigris or both, protected them.

The appearances of the tiger god shrines vary and are made up of wood or rock that are covered with vermilion paste, or stones carved out in the shape of a large cat.

In some areas the large cat is also drawn or carved with other features like the cobra, moon and the sun. Also an image of the tiger is made out of clay is worshiped. At Pench National Park tiger’s pugmarks in clay are worshiped.

Waghoba is known by multiple names such as Waghdev, Waghya, Waghjai, Bagheshwar and Waghjaimata (female form).

Waghoba वाघोबा or Waghya dev

In rural Maharashtra, both tigers and leopards are worshiped as “Waghoba/Waghya dev“.

Wagh is the Marathi word for big cat. The word wagh is used similar to the Hindi word

bagh, which can colloquially refer to both the tiger and the leopard.

“Ba” is a common suffix to indicate respect, a term assigned to an elderly or paternal figure in the community.

Waghoba communities believe that the forest is the realm of the wagh (tiger or leopard) and worship is conducted to appease the big cats so that they do not attack humans within the forest, and also to prevent them from coming into villages.

Waghoba priests claim that at night, the deity comes near the temple as is evident from pug marks which they find the next day.

In order to appease the cats, villagers give sacrificial offering of meat (chicken or goat) in mid-April and in October.

The head of the sacrificed animal is kept at the shrine and the rest of the meat is distributed among people. At a Waghoba temple in Dahibao, South Maharashtra, the villagers spoke to Vidya Athreya and said that once a year the leopard visits the temple and roars.

Waghoba is viewed as the Junglacha Rakhandar, a protector of the forest

Waghro or Vaghro-dev of the Dhangar

Gaudas, Kunbis and Velip are part of Gavli Dhangar communities shepherds, cowherds, buffalo keepers, blanket and wool weavers, butchers and farmers, that live in Maharashtra, northern Karnataka, Goa and Madhya Pradesh.

Vidya Athreya, tells us: In Maharshtra, the Dhangars who are pastoralists, and whose livestock often fall prey to the tiger also view the carnivore as a protector of their livestock.

Besides Biroba, a younger brother of Vithoba the Dhangar’s main God, this group also worships Waghdev/Waghjai, Vaghro-dev, Vyaghambar or Waghro , the tiger-god, believing that worshiping Waghdev will protect their sheep from the tigers and leopards.

The Velip community worship the Waghro statue twice a year with the rituals starting at the time of day when the large cat becomes active (around 8 pm) and lasting for about an hour. The Waghro statues, many of which are over 700 years old, are oiled during each ritual which is attended by all the people in the village.

They also mentioned that the tiger or the leopard often calls during the ritual and until about 20 years ago a tiger would accompany them home from the temple as they would hear the calls all the way back to their houses. (Vidya Athreya, in: Monsters or Gods? Narratives of large cat worship in western India. 2018.)

Vagh-khele performance

The tiger is a character in traditional theater forms of different regions of India – somewhere as a mighty divine form, somewhere as a comical figure to add humor to the traditional plays.

The Gauda and Kunbi communities worship the tiger during the festival of Shigmo in Goa through various rituals and folk dances.

The folk dance and theater of Vagh-khele (which traces its roots to the word khel, which means both play and a dramatic performance) is performed by a player wearing a mask and a costume of a tiger/leopard that displays various behavioral patterns of the predator.

The “tiger” first prays to the folk deity Mayegawas and then performs the Vagh-khel, a scene of attacking and killing a little boy. After this, villagers sacrifice a small chicken and then perform the killing of the beast with a gun.

Tiger cults of East India

The ecosystem of the Sundarbans is rich in ecological diversity, and the livelihood of many depends on the produces of the jongol (forest) itself. Lives are in danger each time they visit the swampy mangroves: fear, is indeed as common as water in the Sundarbans.

In addition to dangerous situations with snakes there is the struggle with the tiger in land and the crocodile on water. There is a popular local saying, ‘‘Jale Kumir, Daangay Baagh’’. (the crocodile on water and the tiger inland)

The worldview of the Sundarbans: The tiger in culture and folklore

[In Sundarbans] Nature does not obey the rules:

fish climb trees, the animals drink salt water; the roots of the trees grow up towards the sky instead of down to earth

– and here, the Tiger do not obey the same rules by which the Tigers elsewhere govern their lives.

Montgomery

In the nineteenth century tigers were killed fueled by stories of man-eating tigers, that developed into myths and legends of startling proportions.

Superstitions were rife among Indians and Europeans alike, and the man-eating tiger also approached the status of a shape-shifting beast, and were-tigers.

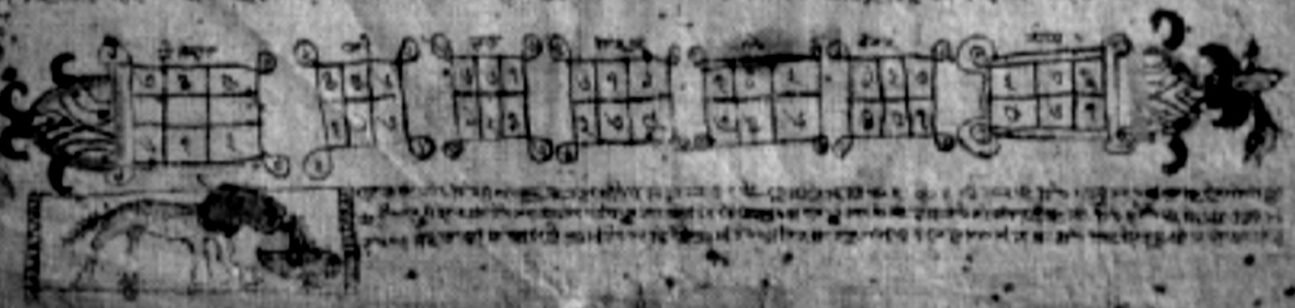

Baul-Fakir mantras for tiger protection

Pradip Kumar Mandal explains, in: A Glimpse of Folk Culture and Religion of The Indian Sundarbans. Scintia, 1(1), 26–28. 2023.

The hard- working jungle goers were quite helpless against the man-eaters of Sundarbans. So, magic was practiced as a security measure. The magicians were mentioned in O’Malleys’ Bengal District Gazetteer as ‘Fakirs’. They are now known as ‘Gunin’ or ‘Boule’ or Baul’.

The word ‘Boule’ should be applied to every jungle goer. But now the word is used for the magician. Bauls and Fakirs, frequently referred to as the wandering minstrels and mystics of Bengal (previously undivided Bengal and now, West Bengal and Bangladesh), are known through their enchanting, often enigmatic songs.

Listen to “Nadia, Baul Fakiri Gaan” – sung by Khejmat Fakir

There are several types of mantras in the Sundarbans, such as ‘Peetu,’ ‘Kaachuli,’ ‘Chaalan,’ ‘Jaalan,’ and ‘Lakshman Gondi.’ According to the faith of the folk communities of Sundarbans, each mantra has separate meanings and power. Each Mantra has its peculiar function.

For example, ‘Lakshman Gondi’ would not allow tigers into a specified area. And ‘Chaalan’ would force any tiger to a direction desired by the Gunin.

Though a distinction is often made between the terms Bauls and Fakirs, in that the Bauls have an exclusively Hindu identity while Fakirs, an Islamic one, in reality, theirs is a syncretic faith, a fusion of both Hindu and Islamic practices, and their common belief is that the body is the sole repository of all experience and means to knowledge.

Mantras, according to some magicians, are not to be uttered openly in public because they might cause danger to that place. Boules or Gunins believe and remain careful so that no mantra enters a goat’s ears. Such practices show the indigenous character of the mantras.

Bonbibi and Dakhin Rai of the Sundarban tribes

The tiger goddess, Banbibi is believed to protect the members of the local community from tiger attacks when they gather honey, wood, or fish.

Before entering the tigers realm, the people seek her blessings for protection against the carnivore.

Banbibi is the guardian spirit of the Sundarbans Mangrove Forests of West Bengal who for some was sent by Allah to save people from tigers.

Banbibi is always represented in an attitude of mild conquest, resembling similar representations of Durga.

The people of the Sundarbans think of her as a “forest superpower” who extends her protection to all her worshipers regardless of the community identities.

For the Hindus she is a devi (Bandurga, Byaghradevi, Bandevi or as Banbibi) and for the Muslim Banbibi is a pirani, a sufi saint.

The narratives of Banbibi are found in several texts named as the Bonbibir Keramati (the magical deeds of Bonbibi) or the Bonbibir Jahuranama (glory to Bonbibi).

These texts consist of two major episodes, her battle with Dakkhin Rai and the narrative of Dukhe.

It is believed that the demon king, Dakkhin- Rai, an arch enemy of Banbibi actually appears in disguise of a tiger and attacks human beings. Banbibir Jahuranama narrates that:

A sage living in the forest turned greedy and refused to share any of the forest resources with humans. Through his ascetic power, he took the form of a tiger called Dakshin (Dakkhin) Rai.

He attacked humans who entered the forest. He legitimized the killing as tax payment with life for the products usurped from the forest.

To end the insatiable greed and terror of Dakshin Rai, God chose a young girl, Bon Bibi, who lived in the same forest.

Folklore describes how Bon Bibi saved Dukhe, a boy, from the clutches of Dakshin Rai. After saving Dukhe from Dakshin Rai, Bon Bibi stipulated that nothing more should be extracted from the forest than what is needed to survive.

As the celebrated author Amitav Ghosh writes in his novel “Jungle Nama,” about the lesson that Dukhe learned from Bonbibi:

Grateful forever to his teacher, Bonbibi, who’d taught him the secret of how to be happy: All you need do, is be content with what you’ve got; to be always craving more is a demon’s lot.

Today, any assault or harm is seen as a result of some misbehavior by the affected, in the present or prior birth, for which the person is punished by the tiger.

Attacks can also happen because the laws of the jungle have been broken, like by cutting green trees or just by harming other species.

Bonbibi is worshiped along with her brother Shah Jangali and Dakkhin Rai.

Her festival is celebrated once a year in January or February.

A Muslim fakir performs the Hazat Puja with offerings of Sirni and fowl.

In the villages of Sundarbans, the legend of Bonbibi is enacted as a stage play (Bonbibi-r Palagaan) to invoke Bonbibi’s blessings.

In his novel Hungry Tide, Amitav Ghosh gives a vivid interpretation of the conflict between the indigenous people of the Sundarbans and the tigers. In the novel, a tiger is accidentally trapped in a livestock pen while trying to carry away a calf.

An angry mob quickly gathers and attacks the incapacitated animal with sharpened staves. A boy thrusts a sharpened bamboo pole through a window and blinds it. Piya, an American cetologist and the central character in the novel, tries her best to save the animal but is helpless in the face of the hostile crowd. Even her associates Horen and Fokir side with the mob and participate in the killing.

Ranjan Chakrabarti, Professor of History at Jadavpur University, Kolkata further writes: Such occurrences are very common in the Sundarbans. The incident portrayed in the novel is illustrative of human-tiger conflict. And the later conversation between Kanai and Piya about the killing of the tiger brings out the essence of the several flashpoints in this complex matter.

Smugglers and poachers, supported by political and business interests and sheltered by local communities, raid the protected forests for valuable exports.

The state exerts its surveillance of the protected forest mainly through the Forest Department, whose officials have been known to exploit their position for private gain, playing a pivotal role in the poaching of timber, deer meat and tiger parts, Ranjan Chakrabarti knows.

Tiger cults of Nord-East India

The Northeast of India is steeped with tiger stories of monstrous tigermen, evil shape-shifters and protecing tiger deities.

The Meitei hunter tribes from Manipur

In Manipur, the tiger was feared but, unlike in other cultures, not widely revered, the overall state policy was to eradicate them.

Known as Pamba or Keirel in earlier times, and simply Kei in the later period, the majestic beast is intrinsic to the worldview of almost all the native communities of the state. The tiger is represented in their narratives of migration and folklore, customs, traditions and institutions.

Khuman Khamba is the hero as well as the protagonist of the Meitei epic poem Khamba Thoibi of the Moirang Shayon legends in the Moirang Kangleirol genres from Ancient Moirang.

The Khoirentak tiger (Meitei: ꯈꯣꯢꯔꯦꯟꯇꯥꯛ ꯀꯤ ꯀꯩꯔꯦꯜ) was a vicious tiger- monster that lived in Khoirentak. The man-eater was killed by Khuman Khamba, when he brought the beast to the capital city of Ancient Moirang, the kings daughter, Thoibi was given to him in marriage.

The Manipuri worldview: The tiger in culture and folklore

The association of the tiger with the Meiteis is as old as their civilization itself. The Meiteis presently constitute a considerable portion of the total population in the state of Manipur, they live also in Assam and Tripura.

Yaiphaba Ningthoujam says, in: Hunted to extinction: Human–tiger interaction in Manipur, India. Manipur University, Imphal. 2024:

The ancient myth of the Meiteis, Panthoibi Khongun, deals with the creation of the universe, the protagonist, Nongpok Ningthou, is depicted as being able to transform himself into a tiger.

Panthoibi, his love and the principal character, is still worshipped, riding a horse or a tiger, as the all-powerful female deity. In Poireiton Khuntokpa, the mythical story of the migration of Poireiton and his companions to the Manipur Valley, what stood in the way between them and the ‘promised land’ was a monstrous man-eating tiger.

As the story goes, a tiger that was hiding in a bush devoured the brave Khomreng, who was asked to lead the way. Only after successfully defeating and driving away the tiger could settlement on the land begin.

Thus, the threat of the tiger to humans has been perceived since the creation of the universe and the settlement of the Meiteis itself, and this persisted until they were completely eradicated.

In fact, the hunting of tigers was taken so seriously in the past that the royal court chronicle of Manipur, the Cheitharol Kumbaba, is replete with instances of them being hunted, mostly under the leadership of the king and his close associates.

Organisations called Keirup, or tiger-clubs, existed all over the kingdom, every village having one. Their main purpose was the ‘ringing and killing’ of tigers as soon as they were located.

Tigers were so abundant and rapacious in Manipur that the state actively supported their systematic hunting until the end of the nineteenth century. Also, rich bounties were placed on the heads of tigers.

After a tiger was captured, in the first half of the nineteenth century, Keiyang Thekpa, was performed.

Literally, the name refers to breaking the spine of a tiger with the bare hands, armed with just a spear, and hence only a few selected men of

valour and kings were allowed to perform this fight.

Men were pitted against the beast in a one-to-one contest for supremacy. Tigers were occasionally made to fight against other animals too.

Due to such persistent killings, coupled with the depletion of their habitat, the number of tigers in Manipur dwindled considerably in the twentieth century, and at present tigers are most probably extinct.

Deep cultural values and beliefs are rooted in Meitei history and folklore, influencing both family and individual behavior. The tiger is ubiquitous as an antagonist in the various folksongs, ballads and stories of Manipur. In most of the lore involving them, a tiger is either the kidnapper or the mauler of the ‘damsel in distress’ and thus must be killed valorously by the male protagonist.

The Meiteis neither revered the tiger nor gave it the cultural prominence that it enjoyed in other societies.

Yaiphaba Ningthoujam

One of the most often repeated folk-tales of Manipur, Keibu-Keioiba, is the story of a shaman turning into a half-tiger, half-human creature as a result of his botched practice of the black arts, and the transformed creature is depicted as both bloodthirsty and an outcast.

He kidnaps a beautiful damsel called Thabaton, whom he makes his wife and keeps in captivity.

The story ends with Keibu-Keioiba being fooled by Thabaton and killed by her brothers.

The tiger, – lawless, savage and menacing beast had to be exterminated at any cost.

Still there is worship of Wangbaren (Wangbren), that has been associated with the warding off sickness and disaster. Wangbaren is black complexion, wears black garment and a black tiger is his mount.

Tiger deities of the Naga

Naga myth: On the creation of the tiger

A legend from Nagaland narrates the story of the first spirit, the first tiger and the first man, all of whom came out of the pangolin’s den, born of the same mother. The man stayed at home, the tiger went to the forest.

One day the man went into the forest where he met the tiger, and the two began to fight. The man tricked the tiger into crossing a river and then killed the tiger with a poisoned dart.

The tiger’s body floated down the river till it lay among the reeds. The god Dingu-Aneni saw that the bones had come from a human womb and and sat on them for ten years, as a result of which hundreds of tigers were born and went to live in the hills and plains.

A popular belief among the Naga tribe is that in spirit, man and tiger are brothers.

The Mao Nagas believed that Ora (spirit), Okhe (tiger) and Omei (man) were brothers born out of the miraculous union of the clouds in the sky and the first woman, called Dziiliamosiiro.

When their mother was dying, the tiger was sent to live in the jungle as he could smell their mother’s dying flesh. The belief that the tiger is a man’s brother meant that the Naga tribe’s people would rarely kill a tiger.

It was believed that, dejected in defeat, the tiger went into the dense jungle and settled there, while the spirit vanished in the far south.

Another version of the story is that the tiger was tricked into living in the jungle by man, which meant that man could not see the cosmic spirit anymore.

The rituals performed to worship the tiger today are in the hope that the three brothers can unite once more.

This holy union of man, nature and the spiritual world forms an underlying theme through many of the beliefs surrounding tigers. While the cosmic spirit refuses to be seen by man, it is up to us to ensure that man doesn’t lose his other brother too.

Naga folklore invokes the tiger as a guardian of the region, who ensured human fertility.

Oaths were taken over a tiger’s tooth or skull and tiger spirits were invoked to cure illnesses.

Some other Naga tribes even killed tigers on ceremonial occasions but strict taboos governed the cutting, skinning and eating of tiger’s flesh.

The head was put in water or the mouth propped open to allow the spirit to escape and prevent the tiger god from avenging his wrath on his killer.

The Lhota Nagas put leaves in the tiger’s mouth for the same purpose while the Lephori kept tiger heads in trees and used them for taking oaths.

The eclipse is explained as the attempt by the tiger to eat the moon or sun, which could be prevented by the loud beating of drums.

Yaiphaba Ningthoujam has collected two myths showing, that the tiger is untrustworthy and bloodthirsty, and hence constitute a constant threat to humankind:

Tangkhul Nagas believed that their ancestors had emerged from a cave at a place on the hill known as Murringphy, which is about a four days journey away in the north-west of the valley of Manipur. In the beginning, no one could leave the cave because it was guarded by a tiger that devoured anyone who attempted to escape.

Only after it was duped and driven away could the Tangkhul Nagas’ ancestors leave the cave. The Anal, Purum and Kom tribes also believed in the ‘cave origin myth’ in which a man-eating tiger stood in the way of their ancestors reaching their ‘promised land’.

The ancestors of those tribes had to kill the tiger to get out of the cave and start their settlement. Thus, the tiger was malevolent and vicious creature that stood in the way of the very foundation of their existence itself.

The Mao people of the Wainganga valley are a Tibeto-Burman major ethnic group of the Nagas inhabiting of Nagaland in Northeast India.

Frazer James G. in 1919, writes about the Bagh Deo worship of the Mao people [sic].

The principle of blood revange of the Kukis

Frazer James G. in 1919, explains:

The Kookies or Kukis of Chittagong, in North- Eastern India, savage people[sic], are of a most vindictive disposition blood must always be shed for blood; if a tiger even kills any of them, near a village, the whole tribe is up in arms, and when, if he is killed, the goes in pursuit of the animal; when, if he is killed, the family of the deceased gives a feast of his flesh, in revenge of his having killed their relation.

And should the tribe fail to destroy the tiger, in this first general pursuit of him, the family of the deceased must still continue the chace; for until they have killed either this, or some other ‘tiger, and have given a feast of his flesh, they are in disgrace in the village, and not associated with by the rest of of the inhabitants.

In like manner, if a tiger destroys one of a hunting party, or of a party of warriors on an hostile

excursion, neither the one nor the other (whatever their success may have been) can return to the village, without being disgraced, unless they kill the tiger. [sic]

North Bengal tiger worship

North Bengal is the place of co-existence among various groups of people. Peer is the sufi saint, that

brings a friendly bondage between the Hindus and Muslims.

In northern Bengal the tiger god was worshiped by both Hindus and Muslims.

Scroll paintings depict a Muslim holy man riding a tiger, carrying a string of prayer beads and a staff. Pir Gazi or Bare Khan Gazi was such a Sufi preacher, Sufi-led villages were centers of the Mughal period.

In another mythological story, a man and a woman in the jungle were prevented by the presence of the Asur Dano (demon) from procreating.

So the woman took a branch of an ebony tree, cut it into pieces and threw them at the Asur. They turned into bears, tigers and hyenas which kept the Asur away. Then they copulated and there were seed and fruit (Thapar 1995).

The myths of the tiger deity are common to other communities of the North-East. The Bodos believe that the tiger was the ancestor of one of their clans. In the Bodo belief system, the tiger is known as Musa while his descendants are known as Musahari or Baglari. The tiger also holds an important position in the Khasi myths. It is regarded as one of the incarnations of U Basa.

Sonarai festival

Sonarai, also written as Sonaraya or Shonarai, is the worship of the tigers in north Bengal, Sona’ refers to the golden hue of tiger’s coat. It is mainly performed by cowherders in eastern India on Pausha Sankranti day (December – January). A couple of days before the Sonarai ritual, young cowherders go from door to door, begging for contributions. They also carry drums and sing rural folk songs.

They participants also carry a bamboo or some reeds knotted together, that serve as a totem. The totem is painted with various colours and decorated with flowers, leaves, and jute fibres, hung vertically. The lead boy (sometimes a man) carries them from house to house.

The householders contribute rice, lentils or money, the alms are used to cook food, that will be offered to the tiger god and for a community feast.

A particular spot is chosen for the worship. The cowherders set up sticks adorned with garlands representing the tiger god or make clay or sholapith idols of Sona Ray, mounted on a tiger and occasionally to Rupa Ray (Sona Ray’s brother), mounted on a goat.

The festival was observed and the tiger god was worshipped in Cooch Behar and Rangpur Districts of undivided Bengal and in Assam’s Goalpara area.

Dāngdhori Māo or Sona Ray – the goddess of tiger of the Koch-Rajbanshis

The Koch-Rajbanshis are a major ethnic community living in Assam and North Bengal, some parts of Bihar, Nepal, and Bangladesh. According to their belief system, the spirit-world forms a part of the totality of being, where man, animals, plants, spirits, and deities remain inseparable parts of the whole.

The god, Sona Ray, is the tiger deity, who protects the faithful from the tiger.

In the Cooch Behar district of North Bengal Dāngdhori Māo or Sona Ray, is worshipped. Once North Bengal was covered with deep forest and various wild beasts were there, who prey on cattle.

The Rajbansis of Cooch Behar would worship this deity for safety of their domestic animals. After the birth of a calf, they worship deity Dāngdhori Māo with bitten rice (chura), milk and ripe bananas. There is a similarity between Dāngdhori Māo and Devi Durgā.

Wildlife Protection through Beliefs and Totems restrict the culling of certain animals and plants. In the North, the Adi tribes of Arunachal Pradesh see tigers, sparrows, and pangolins as well-wishers of humankind so they are not hunted.

One of the septs or sub-tribes of the Eacharis of Assam show traces of their belief in animal descent by going into mourning, fasting, and performing certain funeral rites when a tiger dies.

Garo weretiger-lore

Tigers have historically been a threat to Garo rural settlements. However, only when a tiger had carried off or mauled a villager or a farm animal, was it hunted down by the Garos. A bamboo cage with bait in the form of the kid of a goat or a dog, was used. Once trapped, the animal was killed with a spear or gun. The meat of the slain tiger would only be eaten by males, including, of course, the hunting party.

The Garo tribals, who live in the western highlands of Meghalaya, the southern foothills of Assam and northern Bangladesh, are noted for their diverse beliefs on tigers or matcha. The Garo tiger lore include:

- matchadus: a legendary ‘race’ of shape-shifting tigermen who were the merciless enemies of the Garo tribe,

- matchapilgipas: Garo people whose vital essence (janggi, ‘life, soul’) while dreaming or while in a hypnotic trance moves out of their body and into a real jungle tiger, or into a snake, elephant and even into another human being.

- weretigers: who draw their shape-shifting power from their mastery of magical arts.

- Tiger-shamans’ are powerful shamans who take the tiger as their spirit-guide and who can supposedly perform miraculous cures with its help.

- Durokma, the tigermother

From an episode contained in the Khatta Agana, the cycle of oral epics and heroic ballads of the Garos, one learns that matchadus retain their human form during the day and turn into tigers at nightfall, and then, alone or in a group, follow the trail of cows, goats and humans in order to devour them.

Sometimes Garo heroes succeed in deceiving and killing the tigermen or this ‘race’ of cannibals, half-men and half-tigers, living in their own villages located deep in the forest.

Different sections of the Garo tribe retain in their cultural traditions a complex of supernatural beliefs centering around the idea that all or most of the man-eating tigers prowling around their villages are actually weretigers or matchapilgipas – namely, human beings turned into tigers. (Francesco Brighenti. Feline Metamorphoses of the Living and the Dead among the Kondhs of Odisha. 2004.)

Among the Garos the killing of a man-eating tiger is thought to require a major reparative sacrifice – an ox and two jars of liquor – for the human janggi that might have temporarily occupied the body of the animal at the time of its death.

The only way to sever the link with the tiger is through rites of exorcism arranged by the matchapilgipa’s relatives with the goal to permanently constrain the janggi of the shape-shifter within its original human body.

Durokma – Tiger mother

Garo oral traditions refer to an immortal female being, called Durokma, Dorokma or Dorogma, a ‘matriarchal’ ruler of tigermen (matchadus), as well as the queen of tigers and tigresses – hence her

appellation Matchama, ‘Tiger Mother’. [Bhattacharyya (1995) labels Durokma as a “goddess of monkeys”, most likely because durok is the Garo term for the Bengal loris (Nycticebus bengalensis)].

In epic lore of the Garos she is described as a female tyrant who exercises absolute power of life and death over matchadu warriors. The bravest, most heroic, and most famous matchadu generals were her progeny.

One of Durokma’s legendary abodes is situated on Koasi (or Khoasi) Hill in the northeastern portion of the Garo Hills.

Tigermen used to have annual meetings and sacrifices were held on this hills. The ancient inhabitants of the surrounding country, known as Matchadu Asong (‘the Land of Tigermen’), are said to have worshipped this immortal female being as their tiger-goddess under the name of Koasi Durokma (‘Durokma residing on Koasi Hill’).

The power, attributed to certain persons, to temporarily project their spiritual essence into the body of a a tiger or leopard during sleep or trance is prevalent among the Garos, Khasi and Naga groups in the Assamese region and, further south, some Kondh groups in the state of Orissa.

Bhoi (Khasi) weretiger-lore

The tigerman tradition is most visible among the Bhoi, a community of the Khasis that inhabit the northern section of Meghalaya. Although the Bhoi are predominantly Christians, Khasi religious

beliefs are strong among them. The way of life is primarily agrarian, with paddy cultivation as the mainstay of local economy.

Cat People of Ri Bhoi

Human tigers among the Bhoi are known as khla phuli, and the transformation of a human into a tiger is called ia khla. The etymology of these words is somewhat obscure: although khla literally means “tiger,” or to “become” and khla – “tiger.”

There are two kinds of tiger transformations among the Bhoi:

- The male tigerman – sansaram, literally means “five-clawed.” Contrary to the real tiger which has five claws in its front paws and four in his hind paws – the human tiger has five claws both in his front and the hind paws.

- The khruk that is smaller and usually female.

The tiger- men and women are associated with special sacred places in the forests of Ri Bhoi. One such place is the dwelling of the guardian deity of tiger people of the Makri clan.

The name of this deity is Pdahkyndeng and his dwelling place is a cave called Krem Lymbit which is also home to a large number of bats.

Lyngdoh Margaret, in: Tiger Transformation among the Khasis of Northeastern India Belief Worlds and Shifting Realities. 2016, tells us:

Ha Makri told me that when cattle and livestock are lost, local people attribute this to the tiger deity that feeds on the livestock. Similarly, if a person is lost in this cave then, as my informant explains, the soul-essence or rngiew of that person is chosen by the tiger deity to be his cattle herder.

Finally, it is believed that the bats in this cave comprise the cattle of the tiger deity.

The ability to turn into a tiger is an attribute of the rngiew of a person and it is conferred on the individual by his/her ancestors (syrngi).

A weretiger enters into the realm of ancestral spirits to receive knowledge from them which is then disseminated to the village or clan members.

Tigerwomen and tigermen usually are also the shamans of the clan they belong to. On their death, they become responsible for the wellbeing of the community, participating actively in the further development of the clan. The “Knia Lyngdoh”ritual, which takes place every year is performed for this purpose.

The Lyngdoh, ritual performer, often a tigerman (in the Bhoi context) and also the current maternal uncle of the family offers up betel nuts and leaves to the spirits of as many deceased maternal uncles as he is able to recall. The names of the deceased shamans are spoken out. Then, one name is divined and the spirit of this ancestor becomes the guardian spirit of the clan for one year.

Khasi tiger-men are not malevolent and only special persons are chosen divinely by the ancestors or the tiger deities. In certain cases, the ability is hereditary. The female tigerwoman generally wanders alone.

The woman chosen to become a tigerwoman is special, in the sense that the ability is bestowed upon

her by ancestral spirits of the clan that she belongs to. She is also the only one who can prepare the rice beer to be used in various ritual contexts.

This is one of the most significant functions of the female weretiger, who is also the custodian of the clan essence (longkur), Margaret Lyngdoh explains, in: Tiger Transformation among the Khasis of Northeastern India. Belief Worlds and Shifting Realities. 2016.

How to trasform into a khruk

In an interview held with Swell Lyngdoh at Korstep Village in Ri Bhoi, on 28 December 2012, Margaret Lyngdoh, was narrated the following story of how she first became a tiger woman.

Swell inherited her abilities from her mother’s elder sister.

She told me that the first time she felt the change it was like a dream. She dreamed that she was creeping along the gardens of people in the village and eating their cucumbers. One night, she became aware that she went to the pigsty belonging to a local family and she clawed a pig by its neck.

She dragged the pig by its neck into the forest and left it there underneath a bamboo grove.

Next morning, there was a hue and cry in the village about the disappearance of the pig. It was then that Swell Lyngdoh was able to tell the villagers where to look for the missing pig that she had killed in her tiger state.

While her body slept at home, her tiger went forth.

Her tiger form is coloured black, with white stripes.

Avner Pariat explains: many areas in Meghalaya’s northern Ri Bhoi and Jaintia Hills districts have stories about people who acquire the ability to “inhabit” the body of tigers and leopards. Kong Kel Makr talks about her leopard life in the Interview:

The cat people most never shape-shift into these felines but are reportedly able to link their souls or spirits with the animal. They have a life-long link with the cats and should the animal die or being killed, they also suffer the same fate.

Tiger cults of South India

In 1890, Georgiana Kingscote and Pandit Natesa Sastri recorded a tale from southern India that makes

the origin of an old Tamil proverb:

Sfummd imhhlraija, suruvattai k(i//(if/mn.a,

Be quiet, or I shall show you my original shape.

and features a tiger that turns into a man, not vice versa.

The Brahimin girl that merried a tiger

In a house in the forest there lived a tiger who had acquired great proficiency in magic. Fond of the occasional vegetarian meal, he would assume the shape of an old Brahman, enter a nearby village and share the food prepared for the Brahmans there.

But above all he desired a Brahman wife to cook for him at home, so when he heard that there was a pretty young Brahman girl in the village whose parents were anxious to see married, he assumed the form of a handsome and scholarly young Brahman, sat on a rock by the village burning-ghat, scattered ashes over his head, and began reading out aloud from the Ramayana.

When the girl came to bathe she instantly fell in love with him. Soon they were married, and for a while all went well. But after a month in his in-laws’ house he missed eating meat, so he told them that it was time to take their daughter to live in his own home, which he gave as being in a conveniently distant village.

The walk through the forest was tiring for the girl, but when she said that she wished to rest, her husband scolded her, saying, “Be quiet, or I shall show you my original shape.” Scared of him for the first time, she went on in silence, until at last she could bear it no more and asked again if they might stop. When he answered as before she angrily defied him to do as he threatened, and to her horror he turned into a tiger. Only his voice remained unchanged, as he chillingly told her that he would kill her

if she didn’t live in his house and cook for him every day. Weeping, she followed him to his home.

Every day he brought home meat and vegetables for her to cook, though he took his meals outside and seldom went indoors.

A while later she bore him a son; a tiger cub, conceived when he was in human form. And so the years passed, until one day a crow saw her crying, asked her what was wrong and, on hearing her tale, agreed to help her. With an iron nail she wrote a letter on a palmyra leaf, which the crow took straight to her three brothers. The young men set out at once and on the way collected a donkey, an ant, a palmyra tree and an iron tub.

On their arrival their sister hid them in the loft, as her husband was due home any minute. When he returned he became suspicious and demanded to know who was inside with his wife.