Discover a short history of the domestication of the cow and bull in India, from the Aurochs to the Zebu.

In this Article

Aurochs

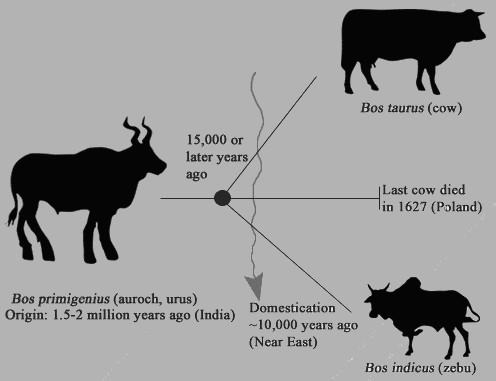

Archaeologists and biologists are agreed that there is strong evidence for two distinct domestication events from aurochs: Bos taurus in the near east about 10,500 years ago, and Bos indicus in the Indus valley of the Indian subcontinent about 7,000 years ago. There may have been a third auroch domesticate in Africa (tentatively called Bos africanus), about 8,500 years ago.

Indian, cattle descended from a sub-species of aurochs who lived at the edge of the Thar Desert, which lies across Bharat and Pakistan.

Scholars at the Paleontologisk Museum, University of Oslo, believe that the aurochs first appeared in India two million years ago, and from there spread throughout the Middle East, Europe and Asia.

Zebu or Bos indicus are thought to be derived from the Indian aurochs, Bos primigenius namadicus. Evidence of the transition of wild to domestic humped cattle, is found in Harappan sites such as Mehrgahr about 7,000 years ago.

Humped bull at Usgalimal Rock Carvings, Goa. Archaeologists believe these carvings can be anywhere from 8,000 – 9,000 years old, dating from the upper Paleolithic to Megalithic period.

Believed to be first bred in northwestern South Asia, between 7,000 – 6,000 B.C., aurochs are understood to have been dispersed throughout northwestern South Asia by 4,000 B.C., and spread across much of South Asia by 2,000 B.C.

Archaeological evidence including depictions on pottery and rocks suggests that it was present in Egypt around 2.000 B.C. and thought to be imported from the Near East or south. It is thought to have first appeared in sub-Saharan Africa between 700 and 1,500 and was introduced to the Horn of Africa around 1,000.

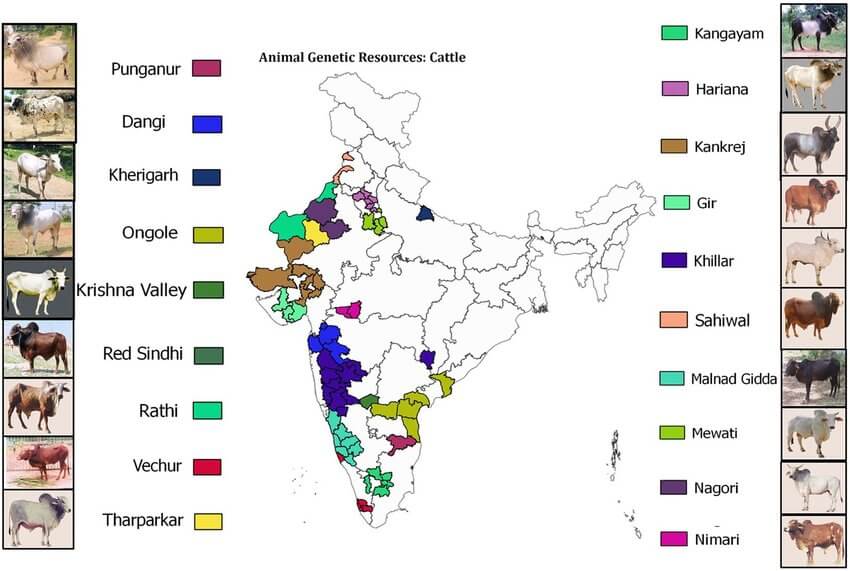

Zebu breeds of India

A large variety of Indo-Pakistani zebu breeds and land races were described in the 19th century. For several breeds herd books were established in the early 20th century.

Since the 19th century a few breeds were exported to Southeast Asia and the Americas. Most zebu breeds are developed as draught cattle, but Sahiwal, Red Sindhi and Gir are specialized dairy cattle and the Kankrej and Ongole are dairy-work cattle. The southern Bharat Mysore breeds were already bred in the 17th century for fast road transport.

Several factors contributed to the recent decrease of the Indo-Pakistani zebu populations:

- increase of mechanized agriculture,

- dwindling grazing areas in densely populated regions,

- exclusion of herds from forest grazing,

- crossbreeding programs,

- increase of the number of dairy water buffaloes.

In India and Pakistan the vast majority of cattle are desi, local animals, also including the nadudana dwarf zebus. However, these countries also count 35 recognized zebu breeds.

Zebu – Indus Valley Civilization (3,000 B.C. – 1,750 B.C.)

It is a fact that the cow, the buffalo and the elephant were domesticated in India long before 3,000 B.C. and in the Pre-Aryan days the massive, long horned and humped form and a small form with short horns (hump less) were found in Bharat, the latter type in the upper strata of Mohenjadaro site.

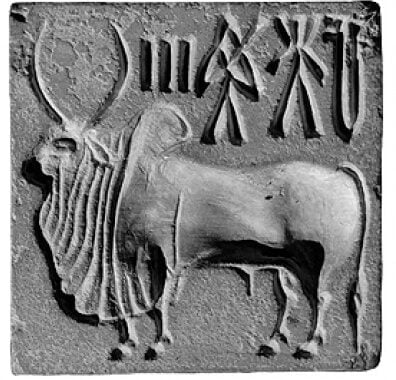

The zebu appears on Harappan seals, among the earliest terracotta figurines found in the subcontinent, and on rock paintings of central India.

Cattle were the main domestic animals of the Indus Valley Civilization, and their bones constitute half of those found in the archaeological sites. This bones bear marks of butchery and are often burnt or charred.

Cows were domesticated for their milk, and bullocks were used for drawing carts, threshing, and raising water; also bulls were kept for breeding. Cattle were essential to the economy, also a medium of exchange. Wealth was estimated by the number of heads of cattle owned either by an individual or the community.

The Pashupati Seal

Pashu means cow and also represents the world of animals, Pashupati is the lord of all animals, of which the cow is the foremost. Pashu is cognate with the Latin pecu, from which are derived words pertaining to money, such as pecunia (Latin) and impecunious (English).

While the identity of the figure has been the subject of much debate, there is a consensus on its supposed associations with the divine. The interpretation of the main figure as Pashupati emerged from the iconography of Shiva – the trishula shape of the headdress (tricephalic, three-headed horned), the yogic pose, the encircling of the figure by animals – leading to its identification as a proto- Shiva or Rudra.

The bovine feature, led some scholars to claim that the figure represented a bovine deity, such as Mahishasura, or a divine bull-man.

Other interpretations suggested identifications with the Vedic deities of Agni, Anila, Indra and Varuna, and with the sage Rishyasringa or the sage Kashyapa. As the inscriptions are yet to be deciphered, the identity of the principal character of the seal remains contested.

This and other archaeological evidence points to the existence of the cult of the bull in the Harappan civilization (3,000-1,750 B.C.) and, while worship of the cow was less popular then, it increased markedly during the Vedic period.

The cow – Zebu in Vedic times (1,500 B.C. — 600 B.C.)

Our knowledge about the Aryans is mostly drawn from Brahmanical sources from the Rig Veda onward. After their migration into the Indian subcontinent pastoralism, nomadism and animal sacrifice remained characteristic features of their life for several centuries until sedentary field agriculture became the mainstay of their livelihood.

The sanctity of cattle may be derived from its economic value.

Milk, ghee, curd, fuel, fertilizer, medicines and disinfectants were all supplied by the cattle.

Even the dowry and bride price were paid in cattle. Also in death the cow will be there to help.

Several Puranas describe the way to the kingdom of Yama, lord of the dead and justice, as arduous. To cross the river Vaitarani the deceased must hold onto the tail of a gracious cow, formerly sacrificed, but in modern times simply rented for a ritual moment.

Not surprisingly, they prayed for cattle and sacrificed them to propitiate their gods. The Vedic gods had no marked dietary preferences. Milk, butter, barley, oxen, goats and sheep were their usual food, though some of them seem to have had their special preferences.

Textual evidence reveals the custom of sacrificing oxen and bulls to the gods and herds of one hundred bulls were legendary offered to Indra. A share of the flesh was afterwards eaten by the people performing the sacrifice, sharing it, was then part of the celebration. Agni was not a tippler like Indra, but was fond of the flesh of horses, bulls and cows.

Soma was the name of an intoxicant but, equally important, of a god, and killing animals (including cattle) for him was basic to most of the Rgvedic yajnas – sacrifice, devotion, worship and offering.

Indra’s companions, the Maruts – storm deities, and the Asvins – gods associated with medicine, health, dawn and sciences, were also offered animals. Maruts or marutagana are the offspring of Rudra and the earth goddess, they had assumed the form of a bull and a cow respectively to create them.

The Vedas mention about 250 animals out of which at least 50 were deemed fit for sacrifice, by implication for divine as well as human consumption. In various legends the gods fight the demons for control of cows (rain clouds).

Cattle are respected by pastoral societies that rely on the animal for their sustenance.

The pastoral Vedic Aryans considered cattle as a major source of wealth, and therefore sacred.

Many cultures gave special reverence to the cow. In Zoroastrianism there is a specific term “geush urva” which has the meaning the spirit of the cow. So honored was this animal it was considered the soul of the earth.

Ancient Egyptians associated the cow with goddess Isis and would not sacrifice it.

In China, as far back as the Tang dynasty (618-907) it was customary to line the banks of rivers with oxen to prevent flooding.

In Bali – Indonesia Animal sacrifice is still practiced, learn more.

Hinduism’s sacred cow is not eaten or killed

Though cattle were sacrificed and their flesh eaten in ancient Bharat, the slaughter of milk-producing cows was increasingly prohibited. According to the Atharva Veda (12.1.15), the earth was created for the enjoyment of not only human beings but also for bipeds and quadrupeds, birds, animals and all other creatures.

The emergence of all life forms from the Supreme Being is expressed in the Mundakopanishad (2.1.7):

From Him, too, gods are produced manyfold,

The celestials, men, cattle, birds.

These ideas led to the concept of ahimsa, non-violence or non injury – the absence of the desire to harm living creatures, the cow came to symbolize a life of nonviolent generosity. Although Sanatana Dharma did not require its adherents to be vegetarians, vegetarianism was recognized as a higher form of living, a belief that continues in contemporary Hinduism where vegetarianism is considered essential for spiritualism.

Around the sixth century B.C., two great religious preachers were born, who took the Upanishadic philosophy of good conduct and non-killing to the people in the common language: Mahavira the Jina (founder of Jainism), and Gautama the Buddha (founder of Buddhism). Both emphasized that ahimsa was essential for a good life.

The degree of veneration afforded the cow is indicated by the use in rites of healing, purification, and penance of the panchagavya. In addition, because her products supplied nourishment, the cow was associated with motherhood and Mother Earth.

The cow was also identified early on with the Brahman priest, and killing the cow was sometimes equated (by Brahmans) with the heinous crime of killing a Brahman.

In the middle of the 1st millennium C.E., cow killing was made a capital offense by the Gupta kings. It is forbidden in parts of the Mahabharata, the Sanskrit epic, and in the religious and ethical code known as the Manu-smirti (“Tradition of Manu”).

Vegetarianism, along with a taboo against beef, became a well accepted mainstream Hindu tradition. This practice was inspired by the beliefs in Hinduism that a soul is present in all living beings, life in all its forms is interconnected, and non-violence towards all creatures is the highest ethical value.

Vegetarianism is a part of Hindu culture, not all Hindus are vegetarians though.

The medieval Indian cookbook, ’Naṣir al-Dīn Shāh’s Book of Delicacies’, Persian: عمتنامه نصیرالدینشاهی, from ca. 1495-1505, describes the preparation of Kheer or milk pudding and Kheema or savory mincemeat.

The book advises that in order to get the sweetest milk for puddings, a well-marked cow should be selected and fed on sugar cane for weeks and her sweet milk then utilized.

The sanctity of the cow entered Mughal culture with Babur, the first Mughal emperor, in his will to his son Humayun, he advised him to respect the cow and avoid cow slaughter.

The Mughal king Akbar chose to ban cow slaughter and thus endeared himself to his Hindu subjects. Legislation against cow killing persisted into the 20th century in many princely states where the monarch was Hindu.

The Constitution Of India 1949, states, in Article 48. Organization of agriculture and animal husbandry:

The State shall endeavor to organize agriculture and animal husbandry on modern and scientific lines and shall, in particular, take steps for preserving and improving the breeds, and prohibiting the slaughter, of cows and calves and other milk and draught cattle.

Today, several State Governments and Union Territories (UTs) have enacted cattle preservation laws in one form or the other. Arunachal Pradesh, Kerala, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Tripura, Lakshadweep, and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands have no legislation. All other states/UTs have enacted legislation to prevent the slaughter of cows and calves and drought cattle.

While exports of cattle beef are banned for religious reasons, buffalo do not hold the same religious significance to most Indians, and buffalo slaughter is legal throughout India. According to the United States Department of Agriculture, India was the global largest beef (water buffalo meat) exporter in 2015.

The slaughter of cows is banned, and the consumption of beef restricted, in most Indian states.

Millions of people in the minority Muslim and lower-caste Hindu communities depend on work in the meat and leather industries. Violence against them from the so-called cow protection groups happens.

Ancient Indian civilization was built on cow products like leather, meat and milk. Today dairy products like milk, ghee, yogurt (curd), paneer (fresh cheese), and buttermilk are essential in everyday cooking across India. They are used in a variety of dishes, from sweets (like rasgulla, kheer and gulab jamun) to savory dishes (such as curries and raitas).

The extents of History, Heritage and Folklore of the cow and the bull in India are hardly to be seized here, there is much more to discover.

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- Arvind Sharma. Schuetze Catherine. Phillips Clive J. C. Public Attitudes towards Cow Welfare and Cow Shelters (Gaushalas) in India. 2019.

- Dallapiccola Anna L. Dictionary of Hindu Lore and Legend.

- DDSA: The practical Sanskrit-English dictionary

- Ganguly Indrajit. Jeevan .C. Singh Sanjeev. SharmaAnurodh. Y-chromosome genetic diversity of Bos indicus cattle in close proximity to the centre of domestication. 2020.

- Harris Marvin. India’s sacred cow.

- https://sharan-india.org/cattle-in-india/

- https://agrotexglobal.com/50-cow-breeds-in-india/

- https://dahd.nic.in/hi/related-links/annex-ii-8-gist-state-legislations-cow-slaughter

- https://discover.hubpages.com/animals/Bull-Festival-aBull-Sport-and-Bull-Worship-In-India#gid=ci027255c1b00324ad&pid=bull-festival-abull-sport-and-bull-worship-in-india-MTc2Mjk3NjI0NDQ4NjcyOTQx

- https://kevinstandagephotography.wordpress.com/2019/03/05/pateshwar-shiva-temple-complex/

- https://sanskritdocuments.org/sites/gomAtA/Cow-Our-Mother.pdf

- https://sharan-india.org/cattle-in-india/

- https://www.bimbima.com/ayurveda/indian-cow-ghee-benefits-medicinal-uses-in-ayurveda/229/

- https://www.bradshawfoundation.com/india/central_india/index.php

- https://www.cowurine.com/science/Urine-Medicine

- https://www.manuscrypts.com/myth/2011/06/30/kamadhenu/

- https://www.mdpi.com/1424-2818/6/4/705/htm

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5884179/

- https://www.sanskritimagazine.com/indian-religions/hinduism/nandi-became-vahan-shiva/

- https://www.speakingtree.in/blog/the-vedic-explanation-of-the-sanskrit-word-go

- https://www.templepurohit.com/nandi-bull-the-vehicle-of-lord-shiva/

- https://www.wisdomlib.org/definition/go

- https://www.etymonline.com/word/cow#etymonline_v_19197

- https://www.sanskritimagazine.com/indian-religions/hinduism/nandi-became-vahan-shiva/

- https://www.speakingtree.in/blog/the-vedic-explanation-of-the-sanskrit-word-go

- https://www.templepurohit.com/nandi-bull-the-vehicle-of-lord-shiva/

- https://web.archive.org/web/20201226173759/https://www.kannadigaworld.com/news/karavali/208423.html

- https://www.wisdomlib.org/definition/go

- Jha, D. N. The Myth of the Holy Cow. 2002.

- Jordan Michael. Dictionary of Gods and Goddesses. 2004.

- https://www.hindu-blog.com/2018/11/story-indra-surabhi-kamadhenu-stotram.html

- Korom, Frank J. 2000. “Holy Cow! The Apotheosis of Zebu, or Why the Cow is Sacred in Hinduism.” Asian Folklore Studies 59, no. 2: 181–203.

- Sharma B.V.V.S.R. The study of cow in Sanskrit literature. 1980. https://archive.org/details/studyofcowinsanskritliteraturesharmab.v.v.s.r.1980_202003_495_U

- Sharma Pratha. Cows in Hinduism. Sanskriti Sanskriti

- Sinha Dharmendra K. Kumar Gupta Atul. Use of cow’s products in ayurvedic medicine. Epidemiology Section, CADRAD, Indian Veterinary Research Institute, Izatnagar. 2007.

- Tadeusz Margul. Present-Day Worship of the Cow in India. Numen, Vol. 15, Fasc. 1.1968. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3269619 .

- The Macmillan Animal Ethics Series. Alsdorf Ludwig. The History of Vegetarianism and Cow-Veneration in India. 2010.

- Valpey Kenneth R. Palgrave. Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics.

- Watch videos on our channel ROADSTORIEZ