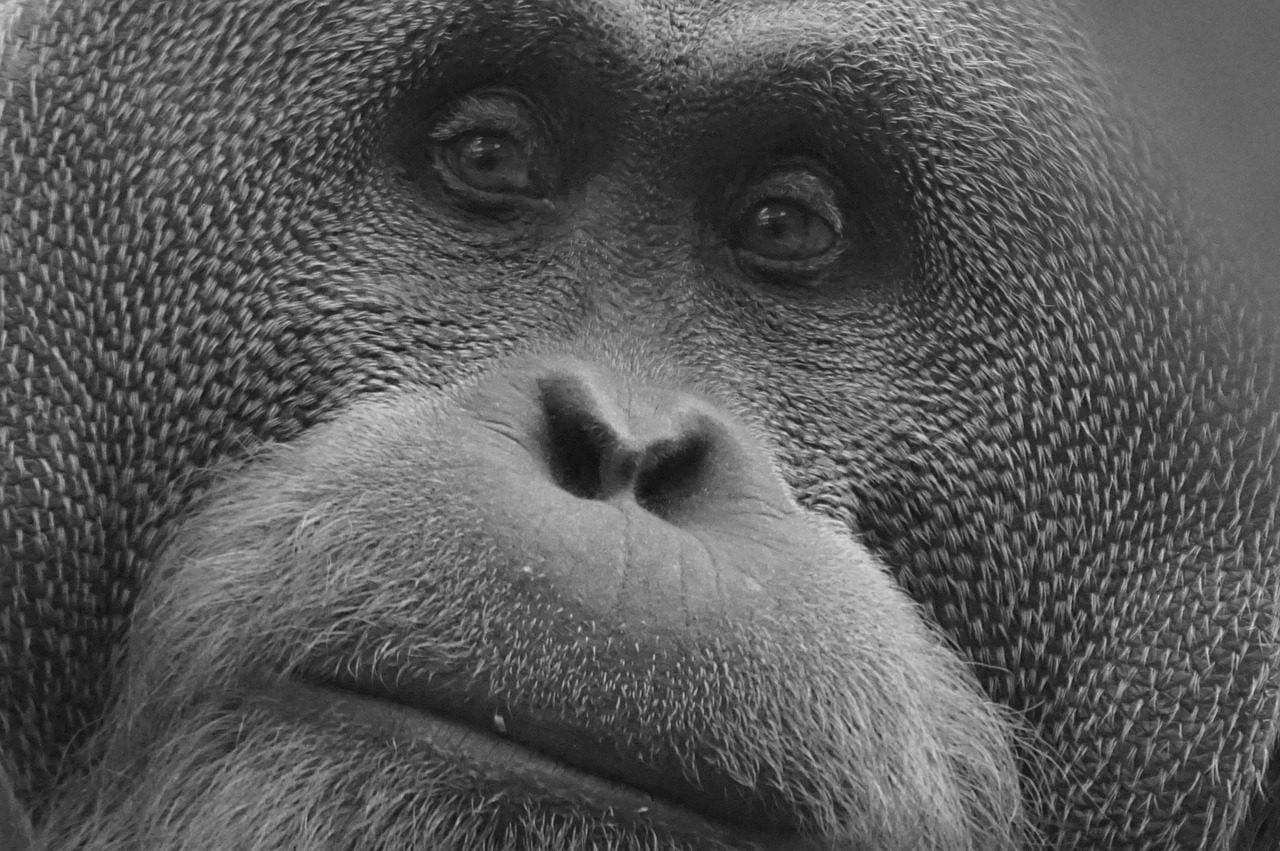

Komodo dragons are the world’s largest living lizards, they only live on a hand full of islands in Indonesia. The crocodile and the Orah, as it is called by the locals, are the closest we have to dinosaurs.

The dragons have long been a source of major fascination for the peoples of Flores who share their islands with them, till today. Discover History, Myth and Folklore of the Komodo Dragon.

In this Article

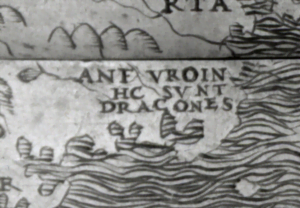

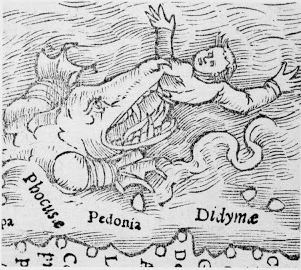

Hic sunt dracones

Dragons and serpents to many-armed beasts that preyed on ships and sailors alike, sea monsters have terrified mariners across all ages and cultures and have become the subject of many legends from the sea. They are known since time immemorial. Medieval cartographers and mapmakers treated their craft like an art, and added fanciful decoration to many of their 15th and 16th century maps in the form of sea creatures and monsters to indicate unexplored areas or areas about which little was known. Narwhals became sea-unicorns, whales became angry, scaled monsters, and mermaids and mermen populated the waters of the world.

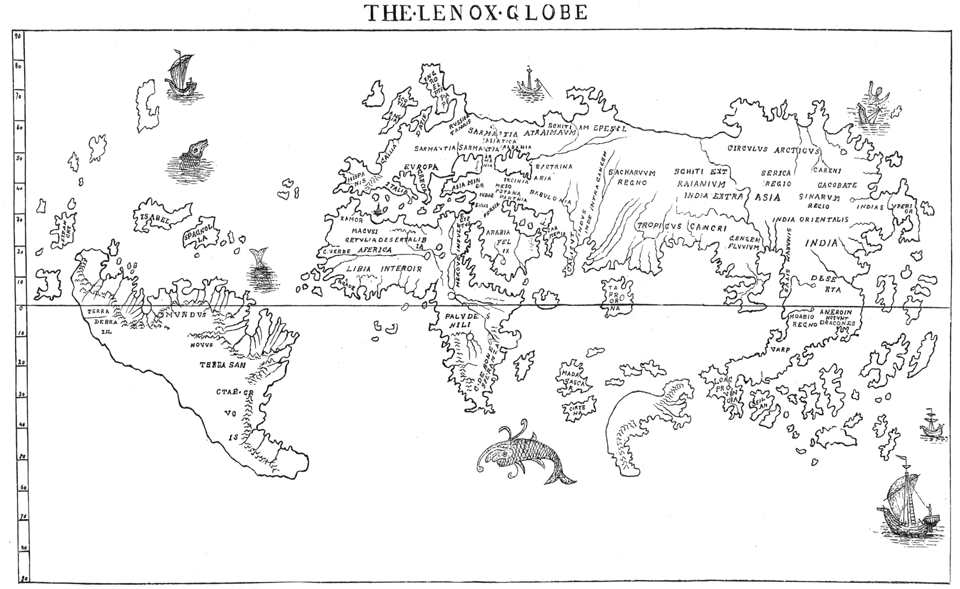

And there were serpents and terrifying dragons swallowing ships. One globe—just one—contains the warning Hic sunt dracones – Here be dragons. Called the Hunt-Lenox Globe, it was built in 1510, making it one of the first European globes ever made.

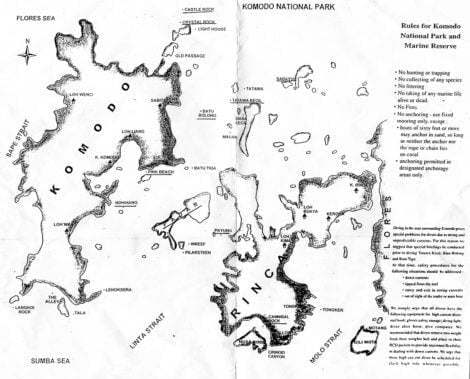

Lands that still deserve this cartographer’s omen, are the Indonesian islands of

- Rinca,

- Gili Mota,

- Flores,

- Paradar and

- Komodo

— the only places in the world where dragons still roam and history, myth and folklore of the Komodo Dragon is still alive.

They are good swimmers and can move from one island to another although sighting them during their ablutions is rare.

ETYMOLOGY: Komodo Dragon – Varanus Komodoensis

The Komodo dragon is also known as the Komodo monitor or the Komodo Island monitor in scientific literature, although these taxonomies are not very common.

Local people called the animal mburu mara and described it as a large “cayman” living only in forests.

(Available lexicographical sources do not permit an analysis of mburu mara, but in related languages, mara can mean ‘dry’ or ‘dry land’.)

This creature “stood high off the ground like a giant iguana” and “would not hesitate to attack humans”

Van Suchtelen 1921.

Local names for Komodo dragon, collected by Auffenberg, 1981:

- Ora (also hora, lawora) Komodo, Rinca, West Manggarai

- Buaya darat (= land crocodile) Komodo, Rinca, West Manggarai

- Rugu (= Ora) Central Manggarai

- Si (also ugu; = lizard) Central Manggarai

- Lio (also ugu, = large monitor/ lizard) Central Manggarai

- Pendugu (Grandfather of Ora) Central Manggarai

- Mbou (= Ora) Central Manggarai

- Biawak raksasa (giant monitor)

The dragon is famous around the world, since it was first discovered in 1911 by a Lieutenant from the Netherlands JKH van Stein. At that time Lieutenant Stein sent photos to the curator of the Musem of Zoology of Bogor, PA Ouwens. Ouwens then set it as a new species and named it Varanus Komodoensis in 1912.

In the Nita dialect of the Sikkanese language the lizards are called bou, a name related to Sikkanese bou ‘uta (‘uta is ‘forest’; Pareira and Lewis 1998), the probable Sikkanese name for the Komodo dragon. Because of their large size, these bou are capable of attacking and killing pigs and goats, in contrast to the smaller and more common water monitors (oti), which at most can kill domestic fowls. Bou will reputedly also chase humans.

Legend: Komodo Dragons transform into crocodiles

Villagers say that when large Komodo dragons enter the sea, they engage in battle with crocodiles, and if defeated, return to the dry land and remain dragons. But if the dragons prove victorious, they stay in the sea and turn into crocodiles.

The Golo Nio believe that Komodo dragons can transform into saltwater crocodiles, both in eastern Indonesia and elsewhere.

Selangor Malays claim that crocodile hatchlings that run in the direction of dry land are eaten by their dams, while any that escape turn into monitor lizards.

The same connection is expressed by the Malay and Indonesian national language term buaya darat, or ‘land crocodile’, which is widely applied to large monitors, and on Flores refers especially to the Komodo dragon.

Similarly, in Tetum, lafaek rai-maran, ‘dry land crocodile’, denotes a “large lizard”, almost certainly a monitor, and some Nage employ ngebu wolo, ‘hill, upland crocodile’, for V. komodoensis. The last term might be a loan translation of buaya darat, an interpretation consistent with the fact that wolo (hill) can contextually mean ‘dry land’ (darat).

Even so, a more direct source may be the Mbai contrast of ebu wolo and ebu ae, referring respectively to the Komodo dragon and the saltwater crocodile (ae is water). People in the Ende regency similarly described the Komodo monitor to Van Suchtelen as a “cayman” living in forests. Finally, Rembong zawa appears to mean both ‘crocodile’ and ‘large monitor’.

EVOLUTIONARY HISTORY

Researchers found that Komodo dragons were most likely evolved in Australia, from a dinosaur called Megalania. This megafauna has been alive around the Pleistocene epoch 50,000 years ago and dispersed westward to its current home in Indonesia.

Around 15 million years ago, a collision between Australia and Southeast Asia allowed these larger varanids to move into what is now the Indonesian archipelago, extending their range as far east as the island of Timor.

Scott Hocknull, a vertebrate paleontologist at the Queensland Museum in Australia, said the ancestor of the Komodo dragon most likely evolved in Australia and spread westward, reaching the Indonesian island of Flores by 900,000 years ago.

Comparisons between fossils and living Komodo dragons on Flores show that the lizard’s body size has remained relatively stable since then. The Komodo dragon is widely known for its unusually large size, the result of island gigantism.

Now, imagine that Varanus priscus was venomous, twice as long and possibly 3 times heavier as a Komodo Dragon- impressive. You rather try to live peacefully with his little sister, a myth and common sense suggests.

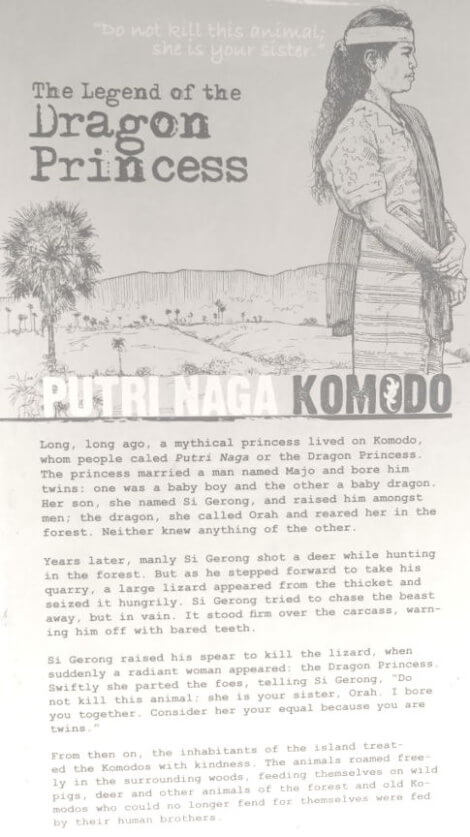

Do not kill this animal – she is your sister

MYTH: Putri Naga or The Dragon Princess of Komodo

Long, long ago when the world seemed much smaller and its creatures much greater, there lived on Komodo Island a man called Empu Najo and his wife, Lea. They were among the first people of Komodo and they lived in a bay called Loh Lavi in Gili Mana, where Empu Najo was the chosen leader of the village.

But the community was constantly attacked by the fearsome Bajo people, nomadic sailors who would openly signal their raids while still far out sea, with a great clashing of swords, held high so that they flashed in the sunlight. At this, Empu Najo and his people would flee to the mountains, returning to find their village plundered of whatever they had left behind.

One day, Empu Najo gathered the villager together and made an announcement. “My people, we must move from this place! The Bajo will attack us until at last we become little more than wild animals.

Let us go instead the mountains, there to live from the bounty of the forest. We shall cultivate gardens, pick fruit and hunt the deer and the wild pigs that are plentiful there.”

And so, high in the mountains, far from the reach of the Bajo, they built houses that were raised platforms made of branches, with roofs of lontar palm (kind of coconut tree).

They grew their gardens and lived in peace, calling their new village Kampung Najo, in honor of the leader who had saved them.

Now it so happened that on their last night in Loh Navi, Empu Najo’s wife Lea had fallen pregnant. By the time the new village was finished, she was ready to give birth – indeed she was experiencing great pain for it is not easy to leave your home and build a new one when you are carrying a child. And there was another problem. The village had no dukun (local doctor), she had been taken by The Bajo even before she had an apprentice.

In those days, without dukun, there was only one way to give birth and that was by the knife. It fell to Empu Najo himself to deliver his child. He made the cut with a steady hand felt for the baby’s head…

As he did so, the wind picked the dry leaves that lay on the ground outside and sent them through the window and into the room where they swirled around lea, lit golden by the last rays of the sun. And then Empu Najo gasped “Sebai!” he said at last “but this is strange-”

Strange indeed, for Lea had given birth to a human son and a twin sister who was far from human. She had speckled, scaly skin, hooded black eyes and a tail. There was no mistaking it.

Tiny as she was, Empu Najo saw in his daughter the characteristics of the giant lizards that roamed the savannah beyond the village boundary. “We have a son” Empu Najo began uncertainly, looking up at his wife. But to his dismay he saw that she was no longer breathing.

There was a little time for Empu Najo to indulge his grief, for he had two newborn babies to bring up alone. His son he named Si Gerong and his daughter, Orah. He fed them goat’s milk and honey and both human and dragon grew quickly. But long before her brother could walk, Orah was already exploring the street outside the house and even climbing trees.

And though the milk sustained her, she was beginning to take an uncommon interest in the neighbor’s chickens. When she actually attacked them, the neighbor complained to Empu Najo “I will give you meat,” he told Najo’s daughter, “but you must not attack our goats and chickens!”

Time passed and though Orah stayed away from the livestock, the villagers grew suspicious of this dragon living among them. Only her father and her brother Si Gerong showed her love. In fact, Si Gerong preferred to play with his sister than with the other children.

The two would climb trees together, the little boy naked but for his shell, or chase the strange looking kalkun birds through the forest. Orah finally ambled back to the house that evening. Si Gerong was overjoyed and embraced his sister, their father smiled, but said nothing. He knew that she had visited with the wild dragons of the Savannah. Orah remained at home for a week before growing restless once again.

This time when she left, she was gone for two days. When she same back, there was no sign that she was hungry and Empu Najo knew then that she had learned to hunt.

And so it went on, except gradually her time in the village grew shorter, while her trips into the forest grew longer, until at last she was coming back to the house just once every ten days or so. One morning, Si Gerong woke to find his sister by his bed. They looked at one another for a long time and then she turned and left. Si Gerong knew that this time, she would not be coming back.

As the years passed, Si Gerong forgot about his dragon sister, perhaps the less to grieve her disappearance. He grew into a man of uncommon skill and wisdom. He was a gentle gardener who could coax even the most stubborn plants to grow and learned to make medicines from the wild herbs he found in the forest.

But he was known first and foremost as an expert hunter. There was not a wild boar elusive enough, nor a deer fleet enough, to avoid his spear, which seemed even able to curve through the air.

One day, Si Gerong was hunting at the edge of the forest close to the Savannah when he heard a rustling close to a stream. He stopped at once and stood stock-still. The deer was a big one – a male with high pointed ears and regal antlers. So confident was he in his abilities, Si Gerong decided to creep closer, hoping to plunge the spear directly into his quarry.

Silently, he approached as the deer drank, until at last he gathered himself and leaped from the underbrush with his spear raised. But, in that instant, another form appeared, rearing onto its hind legs, mouth open and a single eye, black as ebony, fixed on the deer, which stood paralyzed. It was a dragon, the largest Si Gerong had ever seen.

Reflexively, he turned and leveled his spear at the great reptile, for he was loath to lose his prey. The dragon turned its head slightly and lifted itself higher on his forequarters. But as Si Gerong drew back his weapon, a dazzling struck his eyes and he turned his face to the ground. When he looked up again, the deer was gone and there stood before him the radiant figure of a woman.

“Put down your spear, my son,” she told him. “Would you kill your own sister?”

Instantly, all the memories from his childhood came back to him and Si Gerong fell to his knee. “Yes, she is Orah. I bore you together. Consider her your equal because you are sebai.” With this, the vision of their mother disappeared. Man and dragon stared at each other for a long time. Then, as one, they turned away – Si Gerong in the direction of his village, Orah for the Savannah.

From that day forth, Si Gerong and his people treated the dragons with kindness.

The lizards roamed freely in the surrounding woods, feeding themselves on the wild pigs and the deer and the other creatures that dwelt there.

And if a dragon became too old to fend for itself, the people of the village would feed it as though it were a member of their own family.

Visiting The Komodo National Park

Before, Komodo National Park- a UNESCO world heritage site, was created in 1980 to protect the sacred lizards, the residents considered it their duty to appease them with goats and deer. The practice has since been banished, along with the canines that once safeguarded their plots, and rumors say the fork-tongued scavengers are becoming increasingly fearless.

We laze on the deck as we sail Flores Sea and watch islands just from clear water like the backbones of dinosaurs until the rocking lulls me to sleep, after the strong waves of the night I can finally rest.

CC-BY-4.0, edited.

The majestic phinisi have sailed the waters of East Nusa Tenggara for centuries.

The ~ 25-meter schooner we are cruising on nods to the traditional vessels crafted by the Bugis ship makers of South Sulawesi, this ship boasts modern luxuries including a squat toilet, a kitchen and mattresses on the floor for drowsy explorers.

Make a wrong move on Komodo and the local’s ancestors might munch you

Docking at Komodo we’re asked to declare any wounds and menstruation. Smelling blood whips dragons into a craze, so if anyone’s bleeding we’ll need extra guards.

“They look like they’re very lazy, but if they have the chance they’ll eat you,”

cautions Josephus, one of our protectors. I scour my skin for scratches – these three- meter monsters run faster than me, clock in at one-and-a-half times my weight and kill you with a bite, so I’m sure as hell not giving any chances.

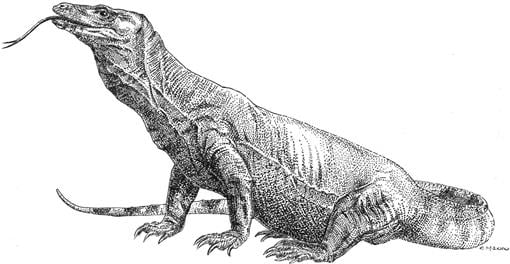

Komodo dragons hunt live prey and are capable of ambushing creatures much larger than themselves. They grow to 3 m or 10 feet long counting the thickly muscled tail and run fast like a dog.

Their preferred method of hunting is to deliver a fatal bite, then follow the prey around until it dies from the resulting bacterial infection, then swallow it in big chunks. A dragon can eat a whopping 80 percent of its body weight in a single feeding.

Once a Komodo dragon maims its prey, it is swallowed whole and later regurgitated in a foul-smelling pellet of hair, bone and other indigestible remains.

We’re warned: be quiet, keep your hands to yourself, don’t stink of fish. Done.

I felt risk-free knowing Noe would bring the latest anti-dragon technology – his forked stick.

Following the ranger’s gaze and seeing through the montage of woods. It is not the monstrous dragon, but its favorite food, the Timur deer that gazes back at me, quietly, perfectly camouflaging with the light and shadows of the landscape.

Half an hour later adrenaline bashes my veins as a dragon lumbers across the baked earth with my exposed limbs set in its sights. A rope of drool dangles from his jaw, his tongue stabs the dusty air and great folds of skin rub at his joints.

I creep backwards and Noe, one of the guards, holds his forked stick (our only protection) tighter.

My shipmates and I have just discovered three dragons chilling near a watering hole in a tamarind forest. Also deeper into the forest we spot full grown dragons peacefully lying around.

“If you like you can do selfie. Get three or four meters close, here, at the back. You can put your hands out and touch the dragon, too”

chirps one of our defenders. I’ll pass.

A baby Komodo darts across the track terrified of us and of the other dragons. Although the mothers lovingly protect their eggs, once hatched all they see are food. So the offspring hide in trees for approximately the first two/three years of their life, foraging for insects, smaller lizards and birds until they are big enough to avoid getting eaten by their cannibalistic peers.

In case we’re unconvinced of their menace, Josephus describes the most recent fatality, a Japanese photographer who was mauled while taking shots of the beasts, he died soon after the bite.

Don’t worry, I think, you won’t die of sepsis from a Komodo bite. You’ll just die when the gigantic lizard with inch-long serrated teeth dripping with hemorrhagic venom tears your flesh to shreds.

I look over to the tree and calculate how fast I could climb it.

After vanquishing the last of my nerves on board with a feast of: rice , cubes of juicy watermelon, tempe [a delicious fermented soybean cake] and spicy sambal, I slip on my fins, chomp onto the snorkel and plunge into the sea.

Whirls of color sway in the clear water, schools of fish stream by and electric blue swimmer crabs dart behind blooms of coral.

Two of the ship’s crew hover in a dinghy nearby, searching the tree line for dragons.

Not only can the creatures dash faster than me, they are also far better swimmers. I pad onto the delicate sand, sit and let the island’s beauty sink in.

In the distance an eagle dives at the surface, latches its talons around a fish and soars away with its lunch.

Out here, it’s eat or be eaten.

SCIENTIFIC MYTH: The legend of the lethal bite of the dragon

It’s no wonder, that for centuries Komodos have been feared by many, with tales of their deadly bite echoing through local cultures and the scientific world. It’s even thought the monstrous lizards may have inspired the mythical beasts that share their name.

– Indonesia . Mia novita ratna siwi. CC-BY-4.0, edited.

Strangely, according to scientists the Komodo bite is not deadly to another Komodo. Dragons wounded in battle with their comrades appear to be unaffected by the otherwise deadly venom. Scientists are searching for antibodies in Komodo blood that may be responsible for saving them.

Biologists have long been intrigued by the success Komodo dragons have at killing big prey. They use an unusual strategy to hunt, lying in ambush and then suddenly delivering a single deep bite, often to the leg or the belly. Sometimes the victim immediately falls, and the lizards can finish it off. But sometimes a bitten animal escapes and may collapse and die later.

SALIVA: Scientists had thought lizards infected prey with bacteria from meat between teeth

They don’t breathe fire but their mouths are so riddled with festering bacteria that one bite is fatal. Their villainous reputation only grew when these fearsome predators were discovered by Europeans in the early twentieth century. But of all the terrible tales told about these dragons, none has been so persistent and pervasive than that of their bite.

The mouths of Komodos are said to be laden with deadly bacteria from the decaying corpses they feed on, microbes so disgustingly virulent that the smallest bite lethally infects prey.

Herpetologist Walter Auffenberg spent an entire year on the island of Komodo in the 80ies, watching and tagging the lizards to learn about their ecology. He noticed that, often, they would fail to kill buffaloes when they attacked. Many of the bitten buffalo succumbed to sepsis, either dying from bacterial infection or so weakened by it that they were easy to eat for the large lizards. This led Auffenberg to the idea that

“induction of wound sepsis and bacteria through the bite of the Komodo dragon may be a mechanism for prey debilitation and mortality.”

New study from team led by Australian university scientist challenges that theory.

Komodos, like other monitor lizards, are close relatives of snakes.

In 2005, Bryan Fry and his colleagues published a paper in Nature showing that all of the species in this clade of reptiles share the same venom genes, suggesting that the early ancestor of all monitor lizards and snakes was venomous.

Bryan Fry and his colleagues show that the bacteria present in Komodo mouths are surprisingly ordinary, similar to what scientists find in any carnivore. Most importantly, the oral flora doesn’t possess the pathogenicity required to kill. They actually have surprisingly good mouth hygiene. As Fry put it:

“After they are done feeding,

they will spend 10 to 15 minutes lip-licking and rubbing their head in the leaves to clean their mouth…

Unlike people have been led to believe, they do not have chunks of rotting flesh from their meals on their teeth, cultivating bacteria.”

The sepsis that weakens and often kill the bitten water buffaloes, is just created by tropical climate and “infected” water, they suggest. The observation of prey dying of sepsis would so be explained by the natural instinct of, who are not native to the islands where the Komodo dragon lives, to run into water after escaping an attack. The warm, feces- filled water would then cause the infections in the water buffalo.

VENOM: A poison gland of killing?

In 2009 Fry and his team captured images of Komodo venom glands using MRI technology and showed that the toxins they produced could cause severe drops in blood pressure- to a mouse, not a bigger creature.

Evolutionary biologist at the University of Connecticut, Kurt Schwenk says that even if the lizards have venom-like proteins in their mouths they may be using them for a different function, and he doubts venom is necessary to explain the effect of a Komodo dragon bite.

“I guarantee that if you had a 10-foot lizard jump out of the bushes and rip your guts out, you would be somewhat still and quiet for a bit, at least until you keeled over from shock and blood loss owing to the fact that your intestines were spread out on the ground in front of you.”

There is an exciting researchers report from July 24 in Nature Ecology & Evolution: The serrated edges and tips of the reptiles’ razor-sharp tooth are lined with a layer of iron. This metal coating may reinforce each tooth, helping Komodo dragons (Varanus komodoensis) safely tear through the flesh of preys.

The dragons teeth are ironclad – literally.

Bottom line

Good scientists groove on an endless quest for knowledge about biodiversity that has evolved over the eons.

~ ○ ~

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- The Hunt-Lenox Globe.

- Djohani-Lapian, Hilly C. Putri Naga The dragon princess of Komodo. 2010. https://indotale.wordpress.com/2014/01/12/the-dragon-princess-of-komodo/

- Eko Armunanto. The origin of all dragon myths: Komodo Dragons of Indonesia. 2013. http://www.digitaljournal.com/article/351891

- Komodo Dragon. 2019.

- Forth Gregory. Folk Knowledge and Distribution of the Komodo Dragon (Varanus komodoensis) on Flores Island. Journal of Ethnobiology 30(2), 289-307, 2010. https://doi.org/10.2993/0278-0771-30.2.289 Komodo Map Laszlo Abel. label.home.cern.ch

- Komodo National Park (UNESCO/NHK).https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H5SOvHu10OQ

- Komodo National Park https://www.national-park.com/welcome-to-komodo-national-park/

- Komodo National Park whc.unesco.org/en/list/609

- Komodo Survival Program, picture, https://www.komododragon.org/post/detail/7

- Megalania or megalania varanus. ( Pleistocene Reptiles Of Australia ).2019.

- Meyer Robinson. No Old Maps Actually Say ‘Here Be Dragons’. But an ancient globe does. 2013. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/12/no-old-maps-actually-say-here-be-dragons/282267/

- Nikola Sarbinowski. Get lost magazine. Issue 46. 2016

- The Real Way Komodo Dragons Kill Prey. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pFaSswGnT0I/

- https://komodomonitor.blogspot.com/

- Wilcox Christie. Here Be Dragons: The Mythic Bite of the Komodo 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20191112041517/http://blogs.discovermagazine.com:80/science-sushi/2013/06/25/here-be-dragons-the-mythic-bite-of-the-komodo/

Keep exploring: