From Ethiopia and Yemen, the habit of drinking coffee traveled to Arabia, Egypt, and Turkey before becoming a dominant beverage in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries. Discover the history and evolution of the coffeehouse and Italian bar culture.

In this Article

History: From Ottoman coffeehouses to the Italian Cafè & Bar

From the Arabian Peninsula, there is mention of roasting and brewing coffee in the 15th century. It was believed that coffee was used by Sufi saints to keep themselves awake during religious rituals. The mythical origins of coffee are steeped in legend and topped with a creamy dollop of speculation.

The coffee trading network was based in the Red Sea region, with the Yemeni port of Mocha as its focal point. Mocha received its supply from Abissinya, the Ethiopian highlands in northeast Africa, the natural habitat of what is now known as Coffea arabica or Arabica coffee.

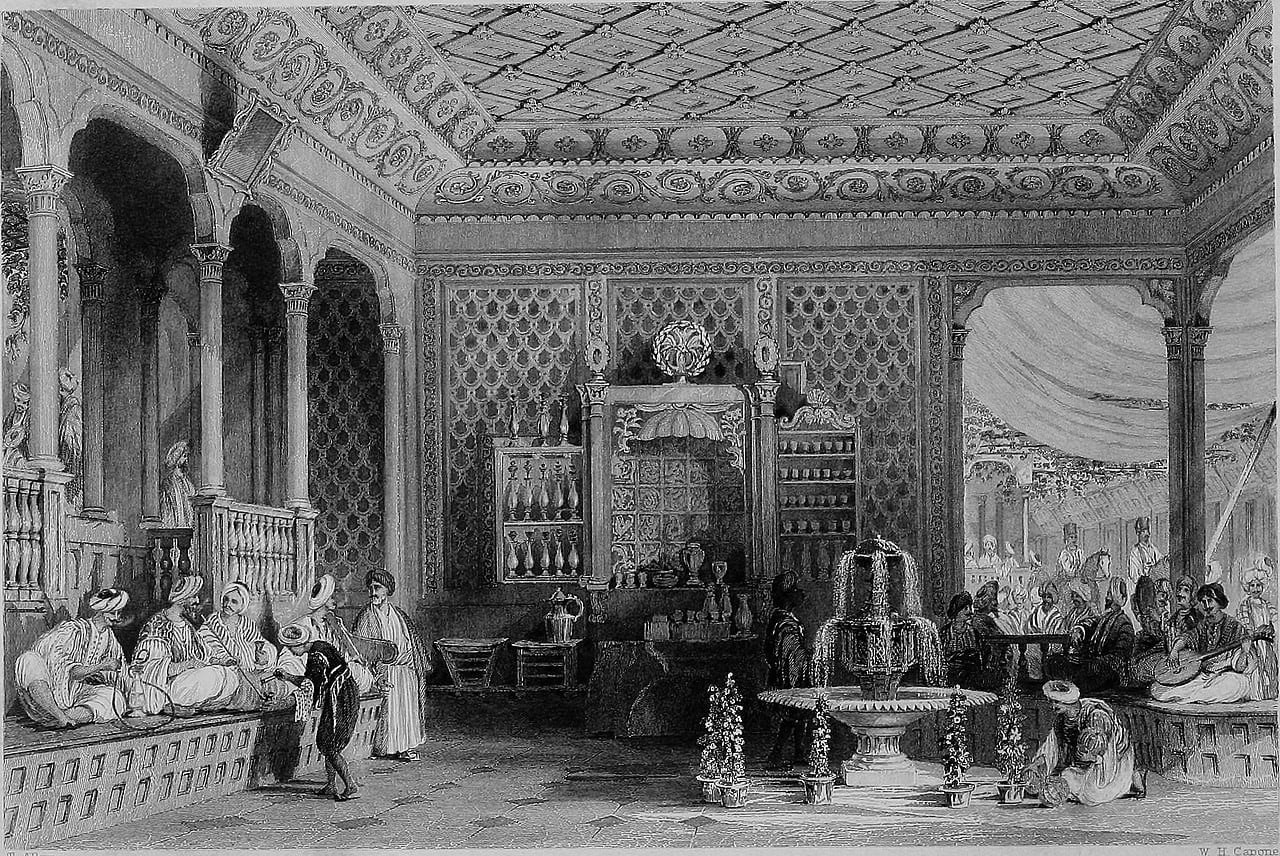

By the 16th century, coffee drinking had spread to the rest of the Middle East, Persia, Turkey, and North Africa. Merchants were disseminating the practice of coffee-drinking to the geographically diverse, but intellectually and linguistically linked Arabs –Ottoman coffeehouses, Iranian Safavid, and South Asian Mughal empires (India) – that reigned from the 16th to the 18th centuries.

Linked to the emergence of the public sphere and, by extension, modern democratic values, Western coffeehouses are effectively the descendants of the dynamic … Arabic coffeehouse culture.

Neha Vermani

Coffee spread to Europe by two routes: from the Ottoman Empire (Vienna), and by sea from the coffee port of Mocha (Venice).

Arab and Ottoman coffeehouses

In 1414, the drink was known in Mecca and in the early 1500s it spread to the Mamluk Sultanate and North Africa. Coffee houses were born in Cairo, especially around the al-Azhar University. Shortly afterwards, they were also opened in Syria, especially in Aleppo. While the first coffee shop on European soil opened in Istanbul in 1475.

There is no coffee shop without coffee and for this reason, the history of the Italian bar begins with the Ottoman Empire in 1500. Coffeehouses are a meeting point where people, far from home, went to smoke, consume coffee while laughing, thinking and discussing current events.

O Coffee! Thou dost dispel all care, thou are the object of desire to the scholar. This is the beverage of the friends of God.

In Praise of Coffee, Arabic poem (1511)

The Arab coffee houses, already known throughout the Middle East up to Ottoman coffeehouses were places for man to drink “Turkish style” coffee. In front of the steaming cups were artists and business people discussing politics, art and literature. Turkish coffee was served strong, black and unfiltered, brewed in an ibrik and served in a finjan (cup) topped with foam.

European Grand Coffee houses or Cafès

The history of the “first” coffeehouse in Europe is highly disputed and interesting. Austrians, French, British and Italians claim the primate of the earliest European coffee cultures – making the conditional obligatory:

The first Austrian Kaffeehaus in Vienna?

Vienna was probably the first European city, that appreciated this black drink so much that the Kaffeehaus (the refined Viennese cafés) were dedicated to coffee and pleasure. By the end of the 17th century, so for Austrian historians.

Legend has it that the fleeing Turks left tents, oxen, camels, sheep, honey, rice, grain, gold—and five hundred huge sacks filled with strange-looking beans that the Viennese thought must be camel fodder. Having no use for camels, they began to burn the bags.

Franz Georg Kolschitzky was a Polish noble, diplomat, and spy during the Great Turkish War. Having observed the Turkish customs, he knew the rudiments of roasting, grinding, and brewing and soon opened a coffeehouse “Zur blauen Flasche” (“To the blue bottle”), in 1683, some say 1684. Apparently, he had introduced the idea of filtering coffee in Vienna.

The first British coffeehouse in Oxford?

In 1650 the first Café was built in Oxford by a legendary Jew named Jacob, the second by a pharmacist, Arthur Tillyard, in 1652 in London, British historians found out.

The first French coffeehouse in Paris?

However, French historians have found evidence of a coffee shop in 1654 Marseilles. Pietro Verri (Italian historian) places it in 1671, saying that it was the first shop that “settled” in Europe.

Indeed, it seems that in Paris, a Levantine already in 1643, that is before the coffee arrived in Marseilles, had occupied a room to make coffee under the Petit Chatelet, between rue Saint Jacques and the Petit Pont. The “very first” Café possibly opened in Paris, in rue Saint André des Arcs, back in 1672, before that in 1670 a Turkish prince, Suleyman Aga, had introduced the custom of drinking coffee in Paris.

In the same period, there were street coffee sellers in Paris, such as that of a hunchback, called “il Candiota“, who went around the streets carrying a basket full of cups hanging from one arm, while in one hand he held a stove with a huge coffee pot and with the other a container full of water equipped with a tap.

German historians state: the first Café opened in Frankfurt dates back to 1689, while in Berlin the Cafés only made their appearance at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

(Excerpted from Mario Scaffidi Abbate, I gloriosi Caffè storici d’Italia. Fra storia, politica, arte, letteratura, costume, patriottismo e libertà.)

American coffeehouses

The first coffeehouse in America opened in Boston, in 1676. After the Boston Tea Party (1773) and the Revolutionary War (1812), Americans began importing high-quality coffee from Latin America.

Whether they were drinking coffee or tea, coffeehouses served a similar purpose to that which they did in Great Britain, as places where business was done. In the 1780s, Merchant’s Coffee House, located on Wall Street in New York City, was home to the organization of the Bank of New York and the New York Chamber of Commerce.

Later coffeehouses in the United States arose from the espresso and pastry-centered Italian coffeehouses of the Italian American immigrant communities in the major U.S. cities, notably New York City’s Little Italy and Greenwich Village, Boston’s North End, and San Francisco’s North Beach.

In the beginning there was the Italian Coffeehouse or Caffè

In Italian, the word caffè is used for the beverage, mainly for espresso as well as for the coffeehouse, that in English it is also spelled cafè.

The first Italian coffeehouse in Venice?

,In Venice, there had long been some knowledge of coffee, because of its economic relationship with the spice trade and its proximity to the Ottoman world. From around 1570 a sizable community of Turkish merchants had lived there, in a house in the Rialto assigned to them by the government.

These men certainly drank coffee in the city, as is attested to by an inventory of the goods of a textile merchant, Huseyin Çelebi, who was murdered in Venice on 20 March 1575. Among the list of his personal belongings and goods, was his tableware, which included his finian (fincan in Turkish) used for drinking coffee. (Markman Ellis quoting Cemal Kafadar, ‘A Death in Venice (1575): Anatolian Muslim Merchants Trading in the Serenissima’,Journal of Turkish Studies, 1986.)

Although there are several slightly different hypotheses, the most accredited is that, in 1580, Venetian botanist and physician Prospero Alpini imported coffee (named Bun at the time) into the Republic of Venice from Egypt. In the 1630s coffee beans were reportedly sold by apothecaries in the city, suggesting that the drink was consumed, at least by some, as a medicine.

Italian historians believe that the first coffee shop arose in Venice. However, some place it in 1647, others in 1676. Historian Lemaire says, Venice’s first registered coffee shop was built in Piazza San Marco, under the portico of the Procuratie Nuove, in 1681, while Daniele Rava claims that it dates back to 1683. It seems that a shop had already been opened in Livorno before Venice, in 1632 founded by a Jewish merchant.

The Italian bottega del caffè – coffee shop

Italy’s coffee culture dates back to the sixteenth century, when the first beans arrived in Venice on one of the trading ships from the Middle East, likely originating in what is now Ethiopia (or perhaps Yemen) when legendary goats were particularly frisky after eating the berries.

Historians agree that Venetian merchants were already importing coffee and the beans were unloaded at Venezia and sold through pharmacies for medicinal purposes. There is evidence that Arab merchants would drink coffee in Venice.

Pope Clement VIII baptized coffee

Legend has it, that at first the Catholic Church opposed coffee drinking. As it was an “infedel” drink, a number of the pope’s advisers appealed to Pope Clement VIII to ban the black brew.

In 1594, the pope initiated an alliance of Christian European powers to take part in the war with the Ottoman Empire. Pope Clement tried “Satan’s drink”, or “bitter invention of Satan”. However, upon tasting coffee, Pope Clement VIII declared: [And here we have two sentences, a humorist and a political incorrect one.]

“Questa bevanda del diavolo è così buona… che dovremmo cercare di ingannarlo e battezzarlo.”

“This devil’s drink is so good… that we should try to deceive him and baptize it.” Pope Clement VIII ?

A nd the other one:

“Why, this Satan’s drink is so delicious that it would be a pity to let the infidels have exclusive use of it.” Pope Clement VIII ?

Clement allegedly blessed or baptized, the bean because, to him, it appeared better for the people than alcoholic beverages. It is not clear whether this is a true story, but it may have been found amusing at the time. The year often cited is 1600, the same year, the Pope Clement VIII in a case of Inquisition presided over the trial for heresy of Giordano Bruno, who was burned at the stake.

Some scholars believe coffee arrived in Naples earlier, from Salerno and its Schuola Medica Salernitana, where the plant came to be used for its medicinal properties between the 14th and 15th centuries.

A widely read pamphlet authored by a gastronome named Pietro Corrado helped spread the new drink, including in his booklet a song praising coffee as the drink of hospitality, friendship, and good wishes. (I could not find much information about this legendary man…).

By the early 18th century, elegant cafés were established and coffee was revered as a luxurious drink, enjoyed by aristocrats. As coffee took hold in the royal courts and as coffeehouses, it proliferated to the point of becoming the defining feature of a newly emerging public sphere.

The popularity of coffee grew rapidly in Italy, not only among the aristocracy, who drank it in their drawing rooms, but also among the folk.

Coffee is sold by street vendors, acquacedratraios, together with lemonade and chocolate drinks. Soon, Italians learned how to roast coffee beans and began drinking coffee at home and at the botteghe del caffè (coffee shops) and coffeehouses.

Cafè – The grand coffee house

Some botteghe (shops), took on particular characteristics that made them shine due to their affinity with literary and political academies: the so-called “Cafè”.

Coffee in Coffeehouses wasn’t Espresso. You would orderal volo, standing with one elbow on the counter, a chat on the fly with frenetic light-heartedness, 2 or 3 sips and moving on with my day. It was much more like a living room, with gentlemen sitting around fashionable tables, polished china cups and tiny pâtisserie or salty snacks on the trays while reading newspapers and talking about politics, art and culture.

The grand cafés were opulent and luxurious, with chandeliers, huge mirrors, comfortable tables and chairs, and formally dressed waiters. The cafés offered an island of gentile peace in the midst of the busy city, a place where business people could discuss finances and intellectuals could discuss philosophy and the state of the world while indulging in coffee and pastries.

Of course, such establishments were by their nature frequented only by those who were well off. Who else had either the time or the money for coffee culture?

What coffee was served in Italian coffeehouses of the 19th century?

In Italy’s original coffee houses, coffee was brewed Turkish style, boiled with spices and sugar in a heated pot. Ottoman coffee is drunk with the grounds settled to the bottom of the cup. Also, filtered coffee is served, with a linen cloth or a small filter over a cup to produce a caffè express, so called because it was prepared expressly for the customer.

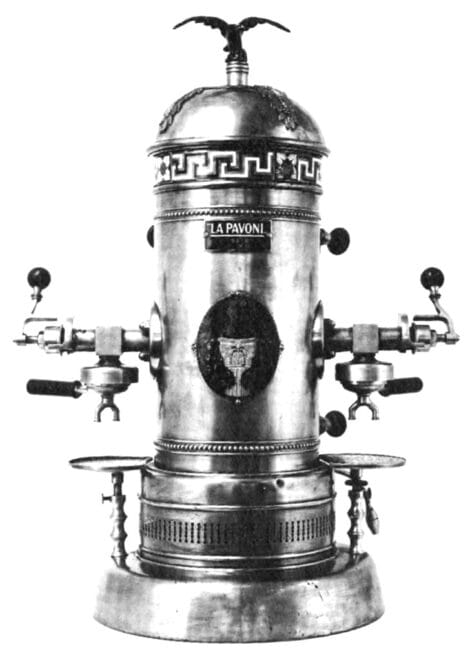

Only in the 19th century was espresso coffee introduced. In 1884, to serve his clients faster, bar and hotel owner Angelo Moriondo (1851–1914) experimented with different extraction methods at his now-defunct Bar (coffee shop) in the Galleria Nazionale di Via Roma and the Hotel Ligure (still around today) in Piazza Carlo Felice in Turin.

Later, Luigi Bezzera (1847–1927) and Desidero Pavoni (1851–1908) invented the removable portafilter espresso coffee machine, la Ideale, an imposing, gorgeous, complicated affair that worked with steam.

Since the introduction of the Ideale machine at the 1906 World’s Fair in Milan, espresso – cafè, has become synonymous with Italian coffeehouses – cafè, and thus Italian cafè culture as a whole.

Though steam power was efficient, it gave coffee a burnt taste.

The modern Espresso era began, when Achille Gaggia (1895–1961), son of a local Milanese bar owner, first developed the “a torchio” system in 1936, and renamed it “Lampo” in 1938.

This disruptive mechanism used hot water pressure instead of steam and prepared a delicious espresso, characterized by a soft layer of “crema naturale”. A true innovation!

The Grand Coffeehouses of Venice under the portico of St. Mark’s Square

The “first caffè” in Italy (or the lands that were to become Italy) rises in the eighteenth century Venice, where in 1720 the famous Caffè Florian opened at the commercial port frequented by Turkish merchants. It was followed by the Pedrocchi of Padua (1722), the Gilli in Florence (1733), the Greco in Rome (1760).

In 1585 Gianfrancesco Morosoni, the Venetian ambassador to Istanbul, told the Senate that the Turkish were drinking a hot black drink, made by a seed called Kahavè and that people had difficulty in falling asleep after drinking this beverage.

This seed was brought back to Venice and in 1638 it was roasted, ground and sold at an expensive price by a special caffè shop which was located directly under the Procuratie.

In 1647, other scholars say 1676 or 1683, the first coffee shop in Italy was opened in Venice under the porticoes of St. Mark’s Square. The New and Old Procuratie, three connected buildings along the perimeter of Saint Mark’s Square, have been the offices of the 9 Procurators, the most important citizens of Venice after the Doge. They controlled the Square, the Basilica and the 6 sections of the city, called sestieri.

Moralists called attention to their all-too-evident “oriental” derivation, suggesting that, coffeehouses were dens of iniquity, gambling, prostitution, and even pederasty.

The Venetians were well known for their love of beautiful women and love affairs were frequent and legendary. Scandals tainted Giacomo Girolamo Casanova became one of the most legendary lovers of Venetian origin but other lesser-known lovers soon filled the State orphanages with their children. Many of these love affairs had their start in the caffès of St.Mark’s Square so in 1767 the government prohibited women from frequenting caffès.

However, Casanova couldn’t resist the charms of the women who strolled about the Square and under the porticos of the Procuratie. He was placed in “Piombi“, the prison, by State Investigators because of his lascivious and anti-religious habits. Casanova attempted to escape twice. The first time, just before finishing a hole in the floor, he was moved to another cell.

The second attempt succeeded, and he made his way out of the Palace and walked directly down the Golden Staircase and out the main entrance! The warders saw him leaving, but they thought he was a politician and didn’t stop him.

Before taking the Gondola to leave the city, he couldn’t resist one last stroll through the Procuratie where he bid his friends goodbye and had one last cup of coffee in his beloved Piazza San Marco. Casanova reached Paris where he lived for 20 years before he was pardoned and allowed to return to Venice.

Venice: Caffè Florian

In 1720, one of the most elegant: “Caffè alla Venezia trionfante” opened its doors. This Caffè of the Triumphant Venice, was a popular meeting point for both foreign and national high society.

Such notables as Carlo Goldoni, the brothers Gozzi and Antonio Canova often spent many hours in this caffè. The caffè’s first owner was Floriano Francesconi, and therefore, the caffè was affectionately called “Florian”.

People from all walks of life frequented Florian, mostly to hear the latest gossip, and Signor Floriano helped in the exchange, for he long concentrated on himself knowledge more varied than that possessed by any individual before or since, Claudia Roden writes. One century later, there were over 200 café in Venezia.

Pietro Longhi, the Venetian old master, in many of his pictures presenting life and manners in Venice during the years of her decadence, shows coffee at elegant homes and coffeehouses.

Carlo Goldoni was a lover of coffee, a regular frequenter of the coffee houses, from which he drew much in the way of inspiration. ‘The Coffee Shop’ (La Bottega del Caffè), a comedy by Goldoni, one of Venice’s most famous playwrights, was first performed in 1750 and provides a flavor of those coffee shops and how their customers drank coffee.

A comedy of bourgeois Venice, satirizing scandal and gambling, vice and virtue alike.

Goldoni was a lover of coffee, a regular frequenter of the coffee houses of his time, from which he drew much in the way of inspiration. In the comedy The Persian Wife, Goldoni gives us a glimpse of coffee making the Turkish way, in the middle of the eighteenth century. He puts these words into the mouth of Curcuma, the slave:

“While putting forth its leaves on one side, upon the other the flowers appear; Born of a rich soil, it wishes shade, or but little sun. Planted every three years is this little tree in the surface of the soil.

The fruit, though truly very small, Should yet grow large enough to become somewhat green. Later, when used, it should be freshly ground. Here is the coffee, ladies, coffee native of Arabia, And carried by the caravans into Ispahan. The coffee of Arabia is certainly always the best. Kept in a warm and dry place and jealously guarded.

- But a small quantity is needed to prepare it.

- Put in the desired quantity and do not spill it over the fire;

- Heat it till the foam rises, then let it subside again away from the fire;

- Do this seven times at least, and coffee is made in a moment.”

The English agricultural writer Arthur Young, visiting Venice in 1788, suggested that

St Mark’s Square and its coffee-houses was ‘the seat of government, of politics and of intrigue’ in Venice.

Florian’s is known to have played host to more illustrious clients such as Jean Jacques Rousseau, Henri Beyle (the writer known as Stendhal), the painter Giuseppe Guardi, Goethe, Marcel Proust and Charles Dickens. Also Silvio Pellico, Lord Byron, Ugo Foscolo and Gabriele d’Annunzio have sat among those tables.

Hippolyte Taine, wrote in, Italy: Florence and Venice, (1869), about the dreamy but temporary world of luxury he experienced visiting café Florian. Taine is intoxicated by the café’s exotic sensuality:

“Taking a seat in the café Florian, in a small cabinet wainscoted with mirrors and decked with agreeable allegorical subjects, one muses with half-closed eyes over the imagery of the day falling into the order of and transformed as in a dream; odorous sorbets melt on the tongue and are rewarmed with exquisite coffee such as is found nowhere else in Europe; one smokes tobacco of the Orient and beholds flower-girls approaching, graceful and handsomely attired in robes of silk, who silently place on the table violets and the narcissus…“

At Caffè Florian, each room has a story and the opulence of the rooms is carefully preserved. Starting from the Sala del Senato, all gold, purple velvet and mirrors, is considered the most important for its historical-artistic value, because the Venice Biennale was born here.

Venice: Caffé Quadri

Across the square, Caffé Quadri opened in 1775 and remains in business since. This historic café also has a revolutionary past. It was a popular haunt for Austrian soldiers when Venice was under Austrian (Habsburg) rule in the 19th century. During the Risorgimento (Italian unification), it played a crucial role, serving as a meeting place for Italian patriots plotting against Habsburg rule.

On May 28, 1775 Giorgio Quadri returned to Venice from Corfu with his Greek wife Naxina. It was her idea to purchase “Il Rimedio” and open a coffee house, even if by this time in Venice they had over 200 competitors, twenty-four of which were located on the Piazza.

Shunned by Italian patriots, Lord Byron and Rousseau were clients of the more bustling, pretentious pro-Austrian Gran Caffè Quadri, located under the arcade of the Procuratorie Vecchie in the Square’s pavement.

1638 a shop owned by Turkish merchants was selling coffee and called “Il Rimedio” or “The Cure” thanks to its sweet wine Malvasia – thought to “reinvigorate the limbs and awaken the spirit”.

Quadri’s guestbook includes Stendhal, Richard Wagner, Marcel Proust, De Balzac, Dumas’ father, and more recently, Gorbachov, Mitterand, and Woody Allen.

Redecorated in 2018 by the ingenious French architect Philippe Starck, Quadri’s is the only restaurant on St. Mark’s Square. Since 2011 it’s been run by the Alajmo family from Padua, owners of Le Calandre with three Michelin stars. Quadri’s has one.

Both Florian’s and Quadri’s have tables in the Square and an orchestra each. Although rivals, they alternate playing music so as not to out-sound each other.

Venice Caffès were frequented by women as well as men.

Soon Milan, Rome, Turin, Genoa, Padua, Naples, Florence and Trieste were under the spell of coffee.

Rome: Caffè Greco

In Rome, one of the most famous coffee-houses was the Caffè Greco, which was established in 1750. Rome was a premier destination for Northern artists from Britain, Germany and Scandinavia who worked in the city. This coterie of painters, sculptors and antiquarians made the Greco their favorite. It was not a large establishment: even in the nineteenth century it only had three small rooms, when the caffè at the Palazzo Ruspoli had seventeen.

Around 1752 the English artists quarreled with their German colleagues and removed en mass to a coffee-house on the Piazza di Spagna, a few hundred meters away. There they established the Caffè degli Inglesi, or English Coffee House. The Caffè degli Inglesi did not survive the Napoleonic wars, however, and in the nineteenth century English, American, German and Danish artists congregated happily together at Caffè Greco. At the Antico Caffè Greco, foreigners could have their mail delivered, and there was a little box dedicated to this purpose.

Its beautiful location in Piazza di Spagna has hosted from philosophers, famous painters to political luminaries and illustrious visitors, like: Arthur Schopenhauer, Buffalo Bill, Canova, Casanova, D’Annunzio, De Chirico, Orson Welles, Wagner, Mark Twain, Sitting Bull, Stendhal, Nietzsche, Pasolini, Andrea Pazienza, Cardinal Gioacchino Pecci who became Pope Leo XIII, Renato Guttuso, Leopardi, Ludovico II of Bavaria and Lord Byron.

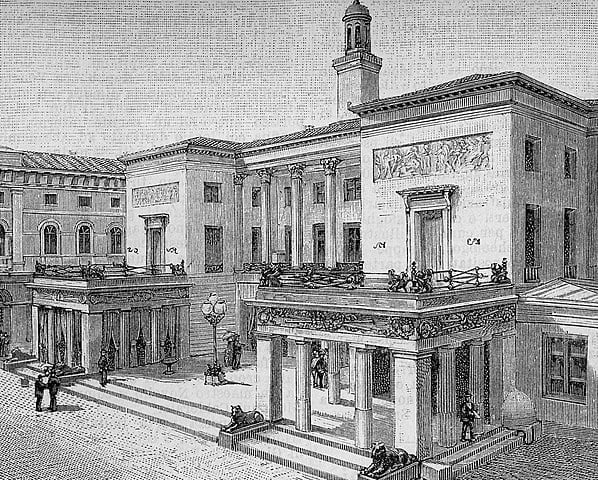

Padova: Caffè Pedrocchi

Meanwhile, of the coffee houses opening across Italy, one of the most beautiful was the Caffè Pedrocchi in Padua. Work on it started in 1816 and it was fully open by 1831.

Its rooms are decorated in a variety of styles. It is acknowledged as one of the finest buildings erected in Italy during the nineteenth century.

It played an important role during the 1848 riots against Habsburg rule, the first uprisings during the Risorgimento: a shot fired by a soldier of the Austrian Empire, the bullet hole still visible today in the white room.

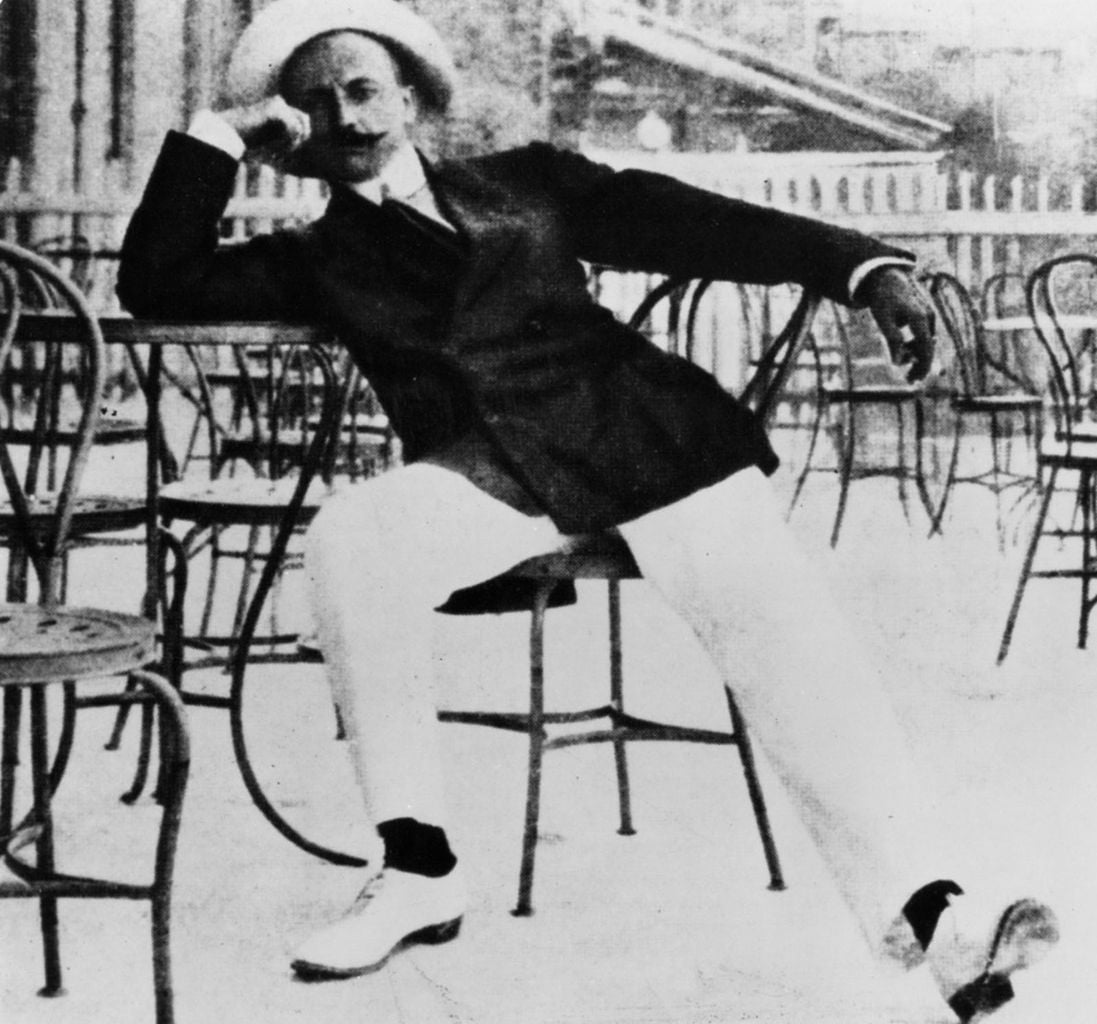

It was frequented by a number of artists and writers, including Lord Byron, Marinetti, D’Annunzio, Stendhal, Balzac and Eleonora Duse.

Florence: Caffè Gilli

Florence’s belle époque Caffè Gilli was opened in 1733 as “La Bottega dei pani dolci, The Small Shop of Sweet Breads” in via dei Calzaiuoli, a refined and welcoming confectionery for the Florentine high society.

However, it was in the second half of the 19th century that Gill experienced his highest notoriety as a literary café and meeting place for many intellectuals.

Artists and painters, like Caligani, Pozzi, Ferroni and Pucci hang out more and more in his frescoed halls. Gilli became a witness of political conflicts and reading place of the first magazines.

From the post-war period onwards, Gilli became a meeting place of young Florentines and the destination of Hollywood celebrities.

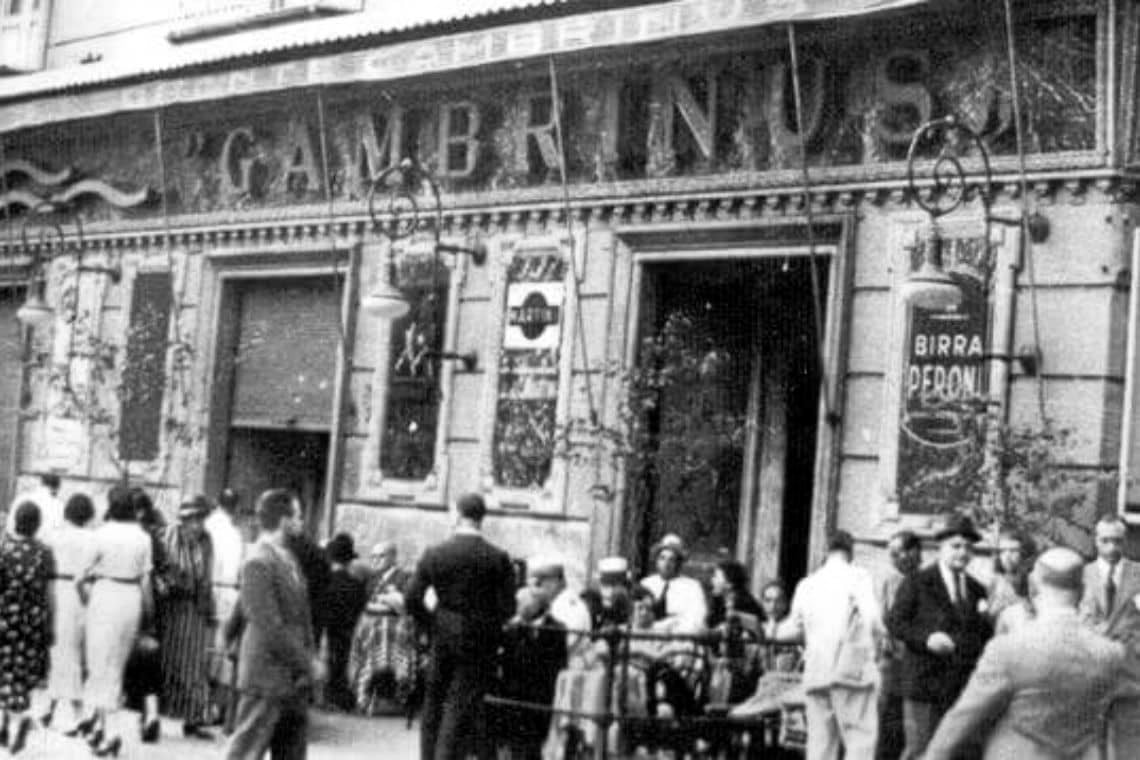

Naples: Caffè Gambrinus

Known as “Cafè of the seven doors” because of its many entrances, the first coffee house was founded in 1860. Today’s name is Gambrinus.

It was known for being a meeting site for intellectuals and artists, including Gabriele D’Annunzio and Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. Oscar Wilde, Ernest Hemingway, Matilde Serao, the Princess Sissi and Jean Paul Sartre, Guy de Maupassant, Émile Zola and Benedetto Croce were also guests there.

Il caffè sospeso or suspended coffee

The finely decorated literary cafè, Caffè Gambrinus, is the birth place of the concept of the caffè sospeso (suspended coffee or pending coffee). A kind gesture that involves paying for a coffee and leaving it for the less fortunate.

People can pay for an extra coffee and put the receipt in a bronze pot. Later, someone in need can come in and use the receipt to get a free coffee.

The heritage of

In Naples and throughout the region of Campania – where the word “cuccuma” originates from – the Neapolitan espresso coffee is not just a brewing pot, but a symbol of Naples’ coffee culture.

The preparation at home with this traditional coffee pot, is part of the daily ritual of drinking espresso. Once used throughout Italy it is now replaced by the Moka pot (patented by Alfonso Bialetti in 1933).

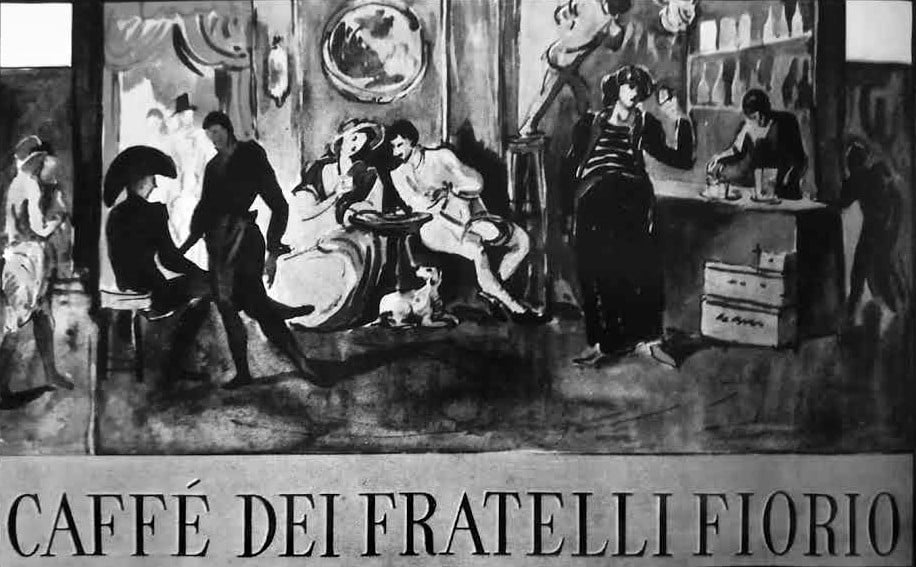

Turin: Caffè Fiorio

Caffè Fiorio, at no. 8 in Via Po. in the late 1800s, was a popular spot for important thinkers like Nietzsche, diplomats, aristocrats, and political leaders of the Italian Risorgimento.

That is why it was nicknamed “Caffè dei codini (pigtails) e dei Machiavelli” or “Caffê Radetzky.”

It consisted of a long room called “il vagone,” the wagon. The walls were lined with mirrors and the seats covered in crimson velvet.

Alongside figures of the aristocracy and the rich bourgeoisie, the Fiorio also hosted famous politicians and literary men, such as Urbano Rattazzi, Massimo d’Azeglio, Camillo Cavour, Giacinto Provana di Collegno, Cesare Balbo, Giovanni Prati and Santorre di Santa Rosa.

Camillo Benso Conte di Cavour, Cesare Balbo and Massimo d’Azeglio, used to sit together in the caffe, all of whom played a role in the founding of the united Italian nation. Cavour founded “Il Risorgimento” in 1847 with Cesare Balbo, and in 1850 Cavour was called by d’Azeglio, then Prime Minister, to be part of his cabinet as Minister of Agriculture and Commerce.

The Fiorio as a political salon was of such importance that, before opening the hearings, King Carlo Alberto (1798 -1849) usually asked

“Che si dice al Caffè Fiorio?”–

“What is in Fiorio said?”

Some say the walking ice cream cone was born in this café.

The heritage of Turin and coffee

In Turin, coffee is part of the lifestyle, the economy and the city’s history: this is home to Italy’s most famous roasteries, like Lavazza, Vergnano and Costadoro. Piedmont is also the birthplace of both the Bialetti moka coffee pot and the espresso machine.

Since 1763, Caffè Al Bicerin is home of the coffee specialty of the same name that has ritually entered the Turin tradition and customers of the caliber of Alexandre Dumas and Cavour have enjoyed it. Il bicerin is a medium tall glass served hot, in chocolate, coffee and cream layers. Turin prides itself by having one of the most antique traditions in chocolate making in Europe (but that’s another story).

The Piedmontese capital can also boast the nineteenth-century Caffè Mulassano, where the tramezzino was born in 1926. Tramezzino is an Italian snack made with soft, white bread, and no crust – a kind of sandwich. The historical Caffè Baratti e Milano in Piazza Castello is listed as cultural heritage.

The heritage of Trieste and coffee

Trieste is a city with Viennese style caffés. The ornate, wood-paneled “grand cafés” here honor the legacy of Vienna. Though the city has a complicated history—it belonged to Italy, Austria (Habsburg), Germany during World War II, Yugoslavia, and finally Italy again.

Caffè Tommaseo is the oldest coffeehouse, dating from 1830. A plaque on the outer wall of the piazza says:

“Da questo Caffè Tommaseo, nel 1848, centro del movimento nazionale, si diffuse la fiamma degli entusiasmi per la libertà italiana”

Tommaseo declares the caffè as “the center of the national movement from which spreads the flame of enthusiasm for Italian liberty” there in 1848 during the period in which Trieste was part of the Hapsburg empire.

Another curiosity of this caffè is that it is said to have introduced gelato, icecream to the city.

Trieste is particularly proud of its literary legacy. Caffè San Marco is where James Joyce finished writing Dubliners and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man in this city; novelist and Trieste native Italo Svevo was a regular too.

At Caffè San Marco, many of the senior professors at the city’s university have their own tables reserved. Coffee in Trieste has a language of its own: You order not espresso but nero, not cappuccino but a capo in tazza grande. Those looking for non-caffeinated cups ask for a deca.

Trieste is home to the famous coffee roasting company Illy, after all.

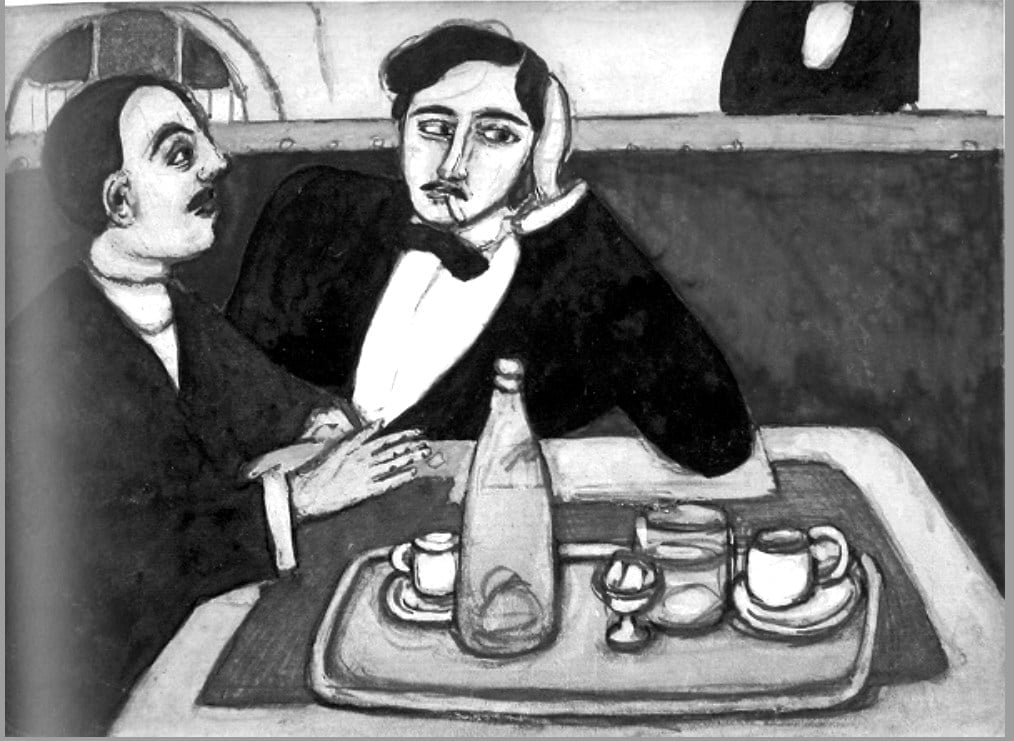

Cafès and restaurants as incubators of modern art

Coffee houses were spaces for gathering, idea exchange, and social interaction. These charming establishments, filled with the irresistible aroma of fresh coffee, did attract people from different cultures and backgrounds, creating a unique environment of conviviality and art, pushing the boundaries of cultural and social norms.

These “Caffès” were meeting places for writers, artists and social innovators; a place to exchange ideas and, sometimes, elaborate works.

Florence: Bar Caffè Giubbe Rosse

Caffé Giubbe Rosse was founded in 1897 with the name of Birreria Fratelli Reininghaus; the restaurant took its current name from the peculiar uniform of the waiters featuring bright red jackets.

The café became the liveliest literary and artistic circle in Florence in the era of Futurism and the usual meeting place for futurists such as Giovanni Papini, Ardengo Soffici, Aldo Palazzeschi. An article written by Soffici criticizing the futurist rivals resulted in a brawl in the Giubbe Rosse between Marinetti‘s Milanese futurists and the Florentine artists around the magazine La Voce.

In the following years of the 20th century, it became a fixed stop for the group of artists and intellectuals who orbited around magazines such as Lacerba, La Voce, Il Selvaggio, Solaria. Among them are Mario Luzi, Elio Vittorini, Alessandro Bonsanti and Umberto Saba.

Representatives of Hermeticism, including Eugenio Montale, also met here. Young Florentine painters, like Ottone Rosai and Primo Conti also visited the Giubbe Rosse. Literary café par excellence, from the years of its birth to today, it has seen personalities such as Giovanni Papini, Ardengo Soffici, Aldo Palazzeschi, Dino Campana, Elio Vittorini, Tommaso Landolfi, Antonio Bueno, Silvio Loffredo and many others sit at its tables. Until the early 2010s, its walls were entirely covered with photos, drawings and memories of its famous patrons.

Milan: Caffè Ristorante Savini

In the heart of the opulent Galleria Vittorio Emanuele Caffè Savini has long been a favorite with the world-famous singers, performers and composers at the nearby La Scala Opera House. Legendary Italian-Greek soprano Maria Callas was a regular, along with composers Verdi, Puccini and director Toscanini.

The restaurant was also the meeting place between Lusignoli, Giolitti‘s emissary, and Mussolini. In 1926, Nobile and Amundsen sat at its tables to plan the flight over the North Pole.

Futurism

In the early 20th century, Savini Milano was also a favourite meeting place for Milan’s intellectuals, writers and artists, including Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876-1944) – leader and founder of the the Futurists. Their historic Futurist Manifesto, signed at the Savini, was published in French newspaper Le Figaro in 1909.

Futurism was an art and social movement. Inspired by the huge innovations happening at the time, from motor cars to aviation and the first fast (espresso) coffee machines, the Futurists celebrated modernity, war (sic!) speed, technological progress and youth… well, the future.

It is not surprising, therefore, that Filippo Tommaso Marinetti was called “the caffeine of Europe”. The greatest spokesperson of futurism considered coffee an instrument that could “free” Europe from the idolatry of the past.

Because it is Caffeine, which is a natural alkaloid that excites the mind. Futurists touched every imaginable creative field, from painting to sculpture, architecture to ceramics, theater to music, and even cuisine.

A recipe from the Futurist Cookbook featured The Excited Pig, Porcoeccitato (formula dell’aeropittore futurista Fillìa). A whole salami, skinned, is cooked in strong espresso coffee and flavored with eau-de-cologne.

As a result of a Fascist campaign for the Italianization of minority peoples and foreign words, starting in the 1920s to the end of the war in 1945, the word barman has been traduced as mescitore – pourer and the bar as – quisibeve – literally, here you drink or bara, ber, bettolino, caffè, liquoreria, taberna potoria and taverna (1941). With the futurist manifesto, new Italian terms are also proposed to replace foreign terms such as “cocktail” which should become “polibibita”, or the “bar”, which becomes “quisibeve”, the “sandwich”, “traidue”. So speaking in futuristic terms, let’s imagine going to the quisibeve and ordering a fresh polibibita.

Futurism anticipated the aesthetics of Art Deco as well as influencing Dada and German Expressionism.

Il Caffè magazine

In Milan, a philosophical and literary publication entitled Il Caffè, The Café, was founded by economist, historian and philosopher, Count Pietro Verri (1728-1797). It was one of the most significant publications of the Enlightenment period in Italy and simulated discussions in a caffé.

From June 1764 to May 1765, the literary and philosophical magazine entitled “Il Caffè” was edited weekly by Pietro Verri and his brother Alessandro. Il Caffè, voiced the Illuminismo effectively and attracted contributions from jurist, philosopher and politician, Cesare Beccaria,(1738-1794).

With the end of Spanish domination and the spread of the ideas of the Enlightenment, from France, political reforms were gradually introduced and the new spirit of the times led people to inquire into the mechanics of economic and social laws.

Although the magazine discussed philosophy, literature and law, in the first issue Pietro Verri made an impassioned argument in favor of coffee, a beverage,

“that brightens the spirit and comforts the soul”.

The count and his friends used to meet at a coffee house in Milan owned by a Greek named Demetrio.

The unique social fabric of Italian caffè

Coffeehouses proliferated to the point of becoming the defining feature of a newly emerging public sphere. It became a place associated with novelty and news. With “modern” activities like the reading of newspapers or books, with commerce, advertising, the promiscuous meeting of social classes, contemporary culture, and, of course, politics, particularly revolutionary politics.

By now, coffee had conquered everyone’s hearts and palates, continuing to be drunk privately in the living rooms of homes. The history of coffee, therefore, continued in the salons and shops of France in 1644, England in 1652, in the United States around 1670, in Germany in 1679.

Having a coffee is a frank moment between the public and the private, an informal meeting place in which to take a well-deserved break from the frenzy of the world.

Espresso is relational. Not just a drink

But Italian coffee is also a cultural experience that reflects our hospitality and conviviality. In Italy, coffee is often enjoyed in company, in homes, cafés and bars, where people meet and socialize. You know you will have your first one for breakfast, the second as a morning break, a third if you meet a friend, and the fourth must follow lunch. Only when you think it is over, will someone pop out asking:

Un caffè?

Let’s have a coffee?

Coffee holds a special place in our collective Italian hearts. “Shall we have a coffee?” is a practical excuse to spend time with friends and family. To us, having a coffee together is more than merely drinking coffee, it is rather a ritual, a moment you deserve, an excuse for gossip, and a time to have a break with your beloved ones having a break from the hustle and bustle of daily routine. Coffee in Italy slides seamlessly into the time for aperitivo: wine, and small plates like crispy bread topped with local cheese and meat.

Espresso is therefore an opportunity for socialization and interaction between people, a moment of relaxation and shared pleasure. Italy has been known as the spiritual home of coffee and the gatekeeper to coffee culture. The reason Italy is thought to be one of the coffee hot spots of the world is the fact that the espresso machine and the Moka pot have been invented and perfected here.

Just around the corner,

There’s a rainbow in the sky.

So let’s have another cup o’ coffee,

And let’s have another piece o’ pie.

Irving Berlin, 1932

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

The history of coffee is an extraordinary study. If you would like to learn more about it, I heartily recommend the book, All About Coffee, by William Ukers. Written in 1928, it will delight you with detail.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20070209232239/https://www.venetia.it/s_proc_eng.htm

- it.wikiquote.org (https://it.m.wikiquote.org/wiki/Voci_e_gridi_di_venditori_napoletani)

Voci e gridi di venditori napoletani - http://90905.homepagemodules.de/t155f59-Cappuccino-Kapuziner-Melange-oder-wie-jetzt.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caff%C3%A8_sospeso

- Allegra World Coffee Portal www.worldcoffeeportal.com

- Artusi Pellegrino. Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well, transl. Murtha Baca and Stephen Sartarelli. 2003.

- Biderman Bob. A people’s history of coffee and cafés. 2013.

- Café Culture Magazine www.cafeculturemagazine.co.uk

- Carosello Bialetti: la caffettiera diventa mito https://www.famigliacristiana.it/video/carosello-bialetti-moka-mito.aspx

- Cociancich Maurizio. Storia dell’ espresso nell’Italia e nel mondo. 100% Espresso Italiano. 2008.

- Comunicaffe International www.comunicaffe.com

- Davids Kenneth. Espresso Ultimate Coffee. 2001.

- De Crescenzo Luciano. Caffè sospeso. Saggezza quotidiana in piccoli sorsi. 2010.

- De Crescenzo. Luciano. Il caffè sospeso.

- Eco Umberto. “La Cuccuma maledetta” in Agostino Narizzano, Caffè: Altre cose semplici. 1989.

- Global Coffee Report www.gcrmag.com

- Gusman Alessandro. Antropologia dell’olfatto. 2004.

- Hippolyte Taine, wrote in, Italy: Florence and Venice, trans J. Durand. 1869.

- https://www.italienaren.org/tradizioni-italiane-caffe-in-ginocchio/

- http://www.archiviograficaitaliana.com/project/322/illycaff

- http://www.baristo.university/userfiles/PDF/INEI-M60-ENG-Public-Regulation-EICH-v4-1.pdf

- http://www.coffeetasters.org/newsletter/en/index.php/category/a-baristas-life/

- http://www.coffeetasters.org/newsletter/it/index.php/il-galateo-del-caffe/01524/

- http://www.culturaacolori.it/fascismo-contro-le-parole-straniere/

- http://www.espressoitaliano.org/en/The-Certified-Italian-Espresso.html

- http://www.inei.coffee/en/Welcome.html

- https://archiviostorico.fondazionefiera.it/entita/585-bialetti-industrie

- https://bialettistory.com/

- https://cdn.intechopen.com/pdfs/55623.pdf Severini Carla. Derossi Antonio. Ricci Ilde. Fiore Anna Giuseppina. Caporizzi Rossella. How Much Caffeine in Coffee Cup? Effects of Processing Operations, Extraction Methods and Variables

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drip_coffee#Cafeti%C3%A8re_du_Belloy

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ISSpresso

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Italian_meal_structure

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neapolitan_flip_coffee_pot

- https://hal.science/hal-00618977/document

- https://hub.jhu.edu/magazine/2023/spring/jonathan-morris-coffee-expert/

- https://ineedcoffee.com/the-story-of-the-bialetti-moka-express/

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caff%C3%A8

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caff%C3%A8#Risvolti_etici_e_sociali

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napoletana

- https://italofonia.info/la-politica-linguistica-del-fascismo-e-la-guerra-ai-barbarismi/

- https://italysegreta.com/italian-hospitality-the-invite/

- https://library.ucdavis.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/LangPrize-2017-ElizabethChan-Project.pdf

- https://memoriediangelina.com/2009/08/11/italian-food-culture-a-primer/

- https://mostre.cab.unipd.it/marsili/en/130/the-everyday-eighteenth-century

- https://napoliparlando.altervista.org/cuccumella-la-caffettiera-napoletana/

- https://specialcoffeeitaly.com/barista-espresso-coffee-machine/

- https://specialcoffeeitaly.com/italian-breakfast-cappuccino-cornetto/?_gl=1*1gjfoya*_ga*OTE0MDM2ODM5LjE2OTMzNjE5OTg.*_ga_2HTE5ZB0JS*MTY5MzM2MTk5Ny4xLjEuMTY5MzM2Mjk0NS4wLjAuMA../

- https://specialcoffeeitaly.com/what-came-first-the-italian-bar-or-coffee/

- https://themokasound.com/

- https://uwyoextension.org/uwnutrition/newsletters/understanding-different-coffee-roasts/

- https://www.adir.unifi.it/rivista/1999/lenzi/cap2.htm

- https://www.bialetti.co.nz/blogs/making-great-coffee/using-bialetti-coffee-makers

- https://www.bialetti.com/ee_au/our-history?___store=ee_au&___from_store=ee_en

- https://www.bialetti.com/it_en/inspiration/post/ground-coffee-for-moka-should-never-be-pressed

- https://www.brepolsonline.net/doi/pdf/10.1484/J.FOOD.1.102222

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/Amsterdam/2014.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/Amsterdam/2014.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/Milan/2013/Gallery/Other/Amalia-Chieco

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/NewYork/2016.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/NewYork/2017.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/NewYork/2018.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/NewYork/2019.aspx

- https://www.coffeeresearch.org/science/aromamain.htm

- https://www.coffeereview.com/coffee-reference/from-crop-to-cup/serving/milk-and-sugar/

- https://www.comitcaf.it/

- https://www.ecf-coffee.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/European-Coffee-Report-2022-2023.pdf

- https://www.espressoitalianotradizionale.it/

- https://www.euronews.com/culture/2022/02/15/the-italian-espresso-makes-a-bid-for-unesco-immortality

- https://www.faema.com/int-en/product/E61/A1352IILI999A/e61-legend

- https://www.finestresullarte.info/en/works-and-artists/the-bialetti-moka-the-ultimate-romantic-design-object

- https://www.finestresullarte.info/opere-e-artisti/moka-bialetti-oggetto-design-ultimi-romantici

- https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/leisure/food/2022/02/15/italy-woos-unesco-with-magic-coffee-ritual/

- https://www.gaggia.com/legacy/

- https://www.gamberorossointernational.com/news/coffee-10-false-myths-to-dispel-on-the-beverage-most-loved-by-italians/

- https://www.gcrmag.com/calls-to-review-price-structure-of-italian-espresso/

- https://www.granaidellamemoria.it/index.php/it/archivi/caffe-espresso-italiano-tradizionale

- https://www.illy.com/en-us/coffee/coffee-preparation/how-to-make-moka-coffee

- https://www.illy.com/en-us/coffee/coffee-preparation/how-to-use-neapolitan-coffee-maker

- https://www.ilpost.it/2011/06/08/itabolario-bar-1897/

- https://www.itstuscany.com/en/bar-where-the-word-comes-from/“Cafe Hawelka”, John A. Irvin

- https://www.lastampa.it/verbano-cusio-ossola/2016/02/17/news/le-ceneri-di-renato-bialetti-nella-sua-moka-con-i-baffi-1.36565348/

- https://www.lavazza.com/en/coffee-secrets/neapolitan-coffee-maker

- https://www.lavazzausa.com/en/recipes-and-coffee-hacks/making-espresso-at-home

- https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/third-wave-coffee-meets-tradition-neapolitan-maker-bruno-lopez

- https://www.mumac.it/we-love-coffee-en/be-our-guest-en/progettazione-e-rito/?lang=en

- https://www.quartacaffe.com/images/pdf/carta-dei-valori.pdf

- https://www.repubblica.it/il-gusto/2021/07/26/news/caffe_il_piu_clamoroso_equivoco_gastronomico_d_italia-311835974/

- https://www.taccuinigastrosofici.it/ita/news/contemporanea/semiotica-alimentare/print/Pop-cibo-di-sostanza-e-circostanza.html

- https://www.thehistoryoflondon.co.uk/coffee-houses/

- https://www.wien.gv.at/english/culture-history/viennese-coffee-culture.html

- Illy Andrea. Viani Rinantonio. Furio Suggi Liverani. Espresso Coffee. The Science of Quality. 2005.

- International Coffee Organization www.ico.org

- Kerr Gordon. A Short History of Coffee. 2021.

- La cremina per il caffè: come farla bene. https://www.lacucinaitaliana.it/news/cucina/come-fare-la-cremina-del-caffe/

- Allen Lee Stewart. Devil’s Cup. A History of the World According to Coffee. 1999.

- Leonetto Cappiello – Wikipedia page on the creator of the 1922 poster La Victoria Aduino.

- Markman Ellis. The Coffee House. A Cultural History. 2005.

- Mennell Stephen. All Manners of Food. Eating and Taste in England and France. 1996.

- Montanari Massimo. Il riposo della polpetta e altre storie intorno al cibo. 2011.

- Montanari Massimo. Il sugo della storia. 2018.

- Morris Jonathan. A Short History of Espresso in Italy and the World. Storia dell’espresso nell’Italia e nel mondo. In M. Cociancich. 100% Espresso Italiano. 2008.

- Morris Jonathan. Coffee: A Global History. 2019.

- Morris Jonathan. Making Italian Espresso, Making Espresso Italian.

- Pazzaglia Riccardo. Odore di Caffe’. 1999.

- Pendergrast Mark. Uncommon Grounds. The History of Coffee and How It Transformed Our World. 2019.

- Perfect Daily Grind www.perfectdailygrind.com

- Scaffidi Abbate Mario. I gloriosi Caffè storici d’Italia. Fra storia, politica, arte, letteratura, costume, patriottismo e libertà. 2014.

- Schnapp Jeffrey. The Romance of Caffeine and Aluminum. Critical Inquiry. 2001.

- Sibal Vatika. Food: Identity of culture and religion. 2018.

- Specialty Coffee Association www.sca.coffee

- Spieler Marlena. A Taste of Naples. 2018.

- Tea and Coffee Trade Journal www.teaandcoffee.net

- The Long History of the Espresso Machine. www.smithsonianmag.com

- The Pleasures and Pains of Coffee by Honore de Balzac

- The relaxation ritual https://themokasound.com/

- Tucker, Catherine M. Coffee Culture: Local Experiences, Global Commensality, Society and Cuture 2011.

- World Coffee Research www.worldcoffeeresearch.org