The taste for a dark, heavy coffee, drunk out of cups, is obviously much older than the Italian espresso machine itself, and stretches back as far as the first Ottoman coffeehouses and Arab homes, possibly even earlier to Ethiopian and Yemenite domestic coffee culture.

The subtle pleasure of sipping an intense cup of coffee has come to be one of life’s indispensable rituals, in Italy we call espresso simply caffè – coffee. We owe much of this pleasure to the coffeemaker. Originally no more than a simple pot, the coffeemaker has evolved into a sophisticated machine, developed and perfected by enthusiasts of the aromatic beverage.

In this Article

Until the early 1900s, coffee in Italy was most commonly prepared with infusion methods such as the Ibrik (or Turkish coffee), a linen cloth or a small filter over a cup to produce a caffè express, so called because it was prepared expressly for the customer. Home coffee makers like the French press, Moka coffee pot and the Neapolitan cuccumella coffee maker predate sophisticated coffee machines. Nonetheless, the Italian Moka Express and Neapolitan flip stove top brewer from 1900s still make a reliably delicious dark coffee using low pressure and without crema.

The dawn of the Espresso Era

Espresso isn’t a specific type of Italian coffee. Rather, it’s an efficient and concentrated brewing method that can be used on any type of coffee grind. This Italian method completely changed the way people enjoy coffee around the globe and even in space. Industrial technology and the ideas of modernity and speed are part of espresso’s cultural symbolism.

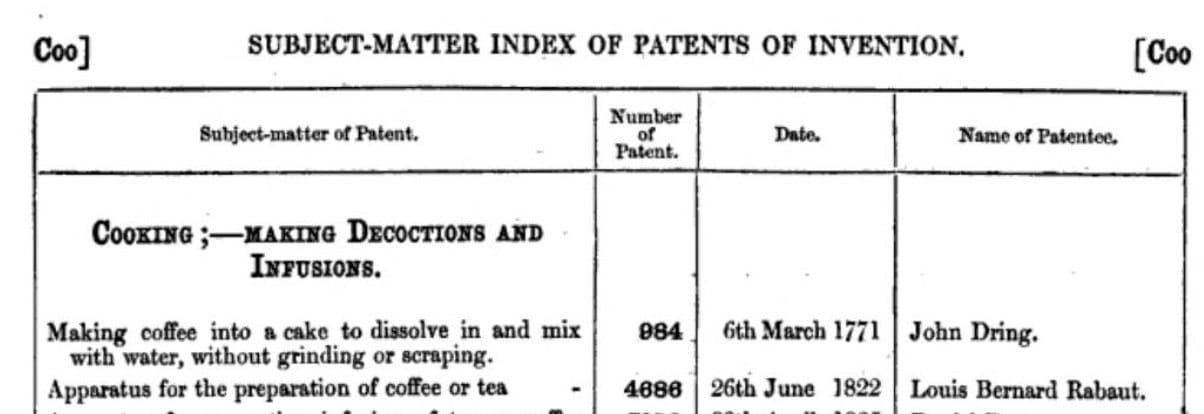

Pre- Espresso: Bernard Rabaut, Edward Loysel and Mallaussina

Experiments with steam pressure brewing have been undertaken in Britain and France as far back as the early 1800s. The French case rests on the machine invented in 1822 by Louise Bernard Rabaut and refined by Edouard Loysel de la Lantais that was a spectacular success at the Paris Exhibition of 1855.

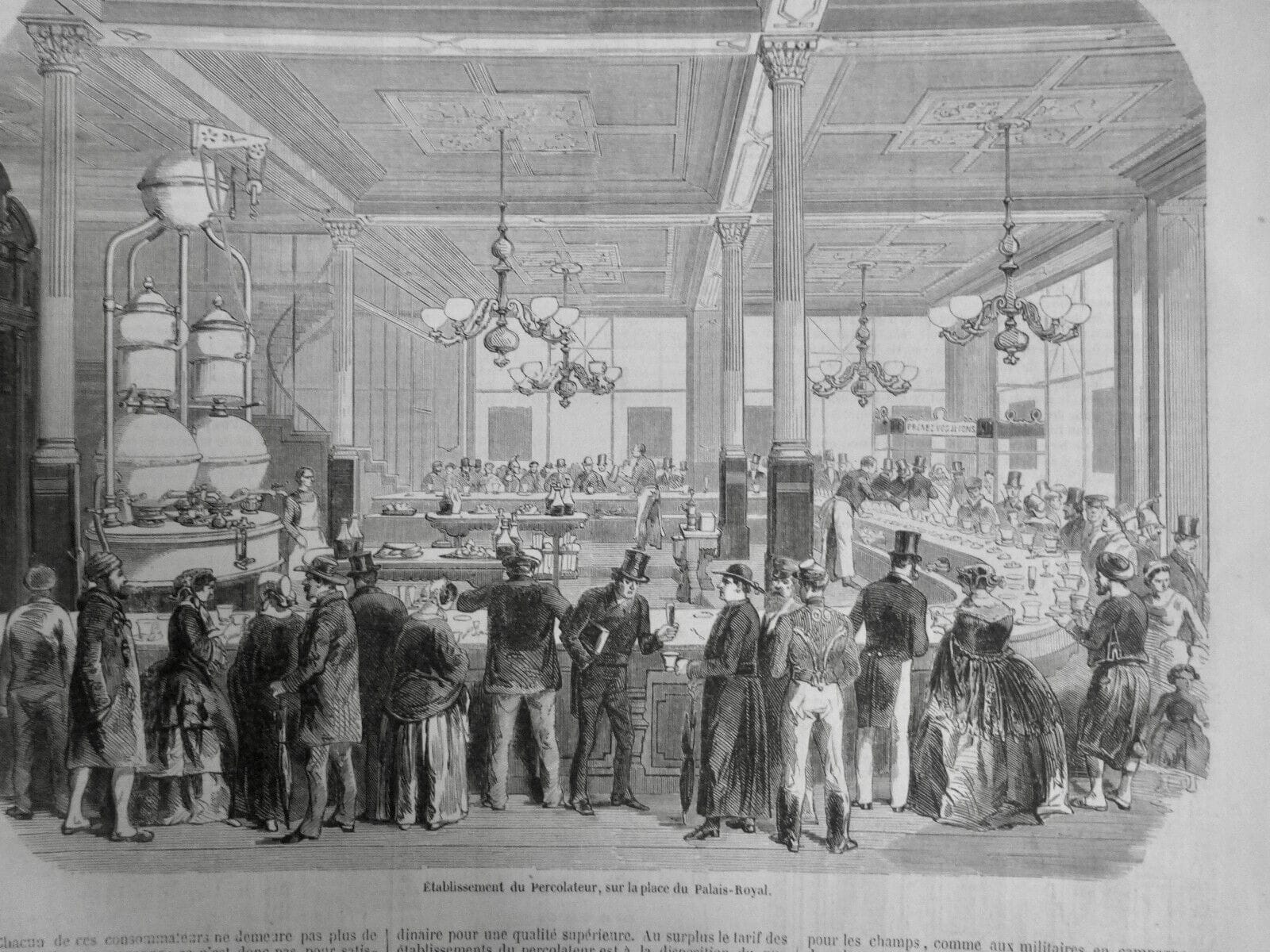

With his invention, Loysel mainly solved the problem of having a large quantity of coffee to serve in a (relatively) short time, his hydrostatic percolator, was capable of producing 2,000 cups of coffee per hour. The machine, which works mechanically and does not use steam, was not exclusively designed for coffee and solved a number of needs.

It could be used to prepare tea, coffee, hot chocolate, but also malt infusion for brewing beer or medicinal plants as a base for medicines. He is also the person who attached the name percolator to these new coffee machine precursor.

However little is known about the french inventor Mallaussina, from Nizza, who might have perfected the method of espresso brewing.

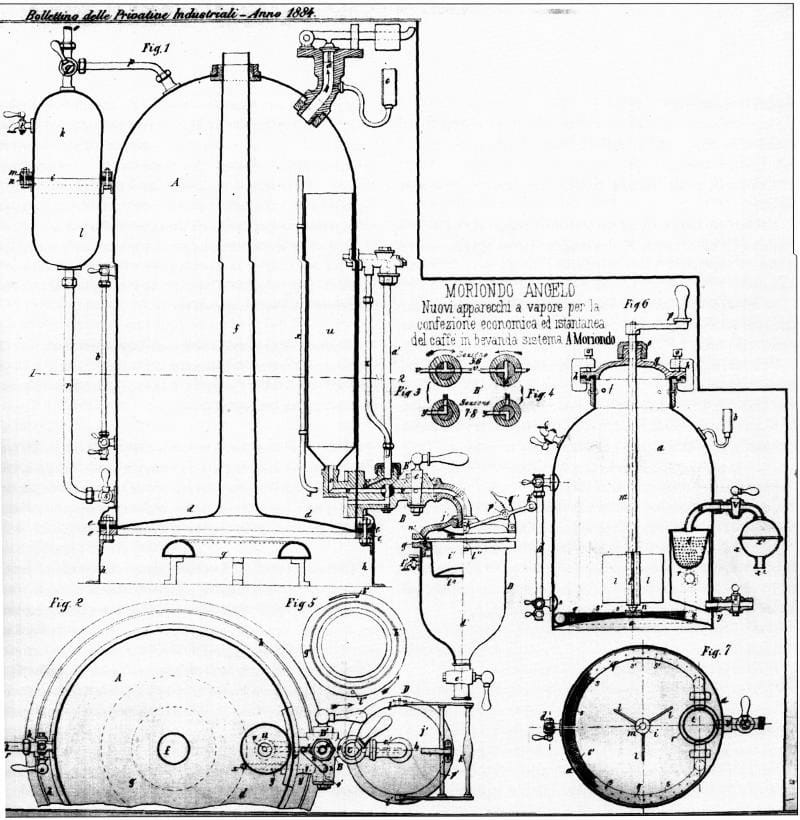

Angelo Moriondo – New steam machinery for the economic and instantaneous confection of coffee beverage

In 1884, to serve his clients faster, bar and hotel owner Angelo Moriondo (1851–1914) was the first to experiment with different extraction methods at his now-defunct Bar (coffee shop) in the Galleria Nazionale di Via Roma and the Hotel Ligure (still around today) in Piazza Carlo Felice in Turin.

He patented the invention of “new steam machinery for the economic and instantaneous confection of coffee beverage. System A. Moriondo – Nuovi apparecchi a vapore per la confezione economica ed istantanea del caffè in bevanda. Sistema A. Moriondo”

The machine consisted of a large boiler that pushed the heated water through a bed of coffee grounds and extracted them with the water’s steam. The pressure generated was only around 1.5 bars, meaning that no crema formed on top of the coffee liquor.

The high temperatures of around 130-140C in the groups and the almost inevitable contact with the steam scalded the coffee cake, so the eventual espresso was black in color, smelled burnt, and tasted bitter. It was delivered in around forty-five seconds and served in a significantly larger volume than today.

The taste was like a somewhat concentrated filter coffee. This very creative system turned out to be rather inconvenient and never passed the prototype stage, so Jeffrey Schnapp, American university professor at Harvard University, cultural historian, designer, and technologist.

With the exception of his patent, the life of Moriondo has been largely lost to history.

The progenitor of the Italian caffé espresso machine – Luigi Bezzera and Desiderio Pavoni

The word espresso was borrowed from the English express via the French expris, meaning something made to order and, by extension, produced and delivered with dispatch.

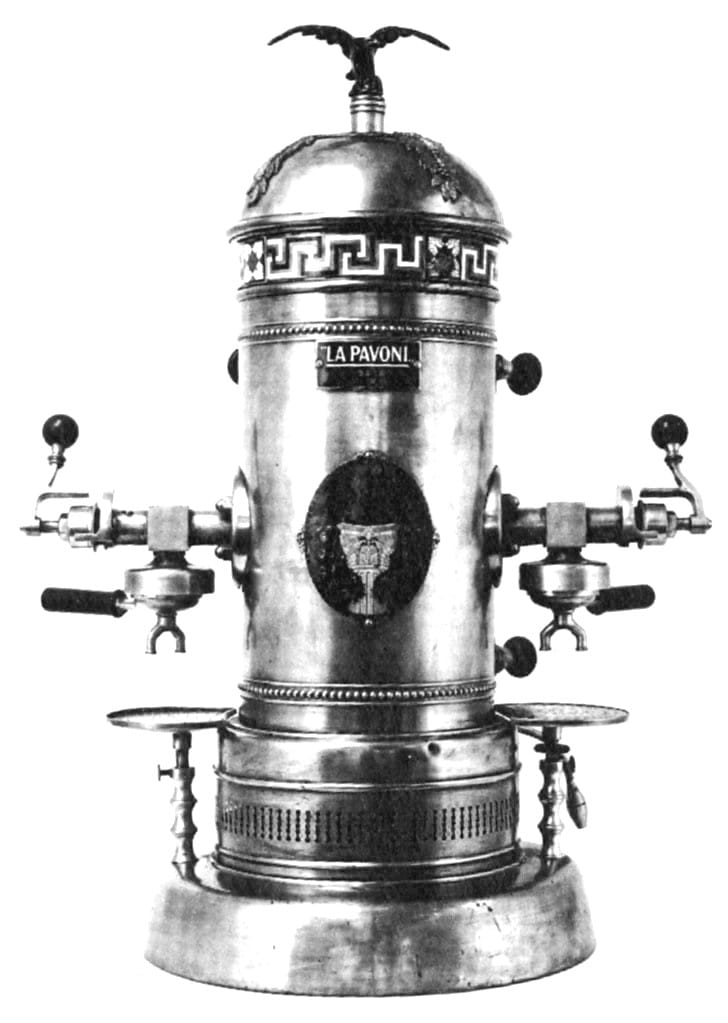

In 1901 an Italian named Luigi Bezzera (1847–1927) invented the removable portafilter espresso coffee machine, an imposing, gorgeous, complicated affair with assorted spigots, handles, and gauges, some topped with a resplendent eagle. The machine was heated over an open flame, which made it difficult to control pressure and temperature, and nearly impossible to to produce a consistent coffee.

Bezzera’s patent was acquired by the manufacturer Desidero Pavoni (1851–1908) whose Ideale machine of 1905 is also recognized as the first machine – to be called espresso, literally meaning express or instant – to enter into commercial production.

Notably, Pavoni invented the first pressure release valve. This meant that hot coffee wouldn’t splash all over the barista from the instant release of pressure, further expediting the brewing process and earning the gratitude of baristas everywhere.

Bezzera and Pavoni worked together to perfect their machine, which Pavoni dubbed the Ideale.

Luigi Bezzerra and Desiderio Pavoni introduced caffè espresso at the 1906 Milan International World’s Fair.

However, the system used the extreme heat of the water in the machine (at a temperature considerably above boiling point) to maintain the pressure needed to force the water through the grounds, which meant that the coffee grounds were over-extracted and the resulting liquor bitter. The brew was dark, concentrated, and satiny, with a rich hazel-colored crema on top.

Nonetheless, the speed of the service and the dramatics of its production, amid clouds of steam, found favor with customers all over Europe. By the 1930s these had spread to cafés all over Europe and to Italian restaurants in the United States.

Pier Teresio Arduino

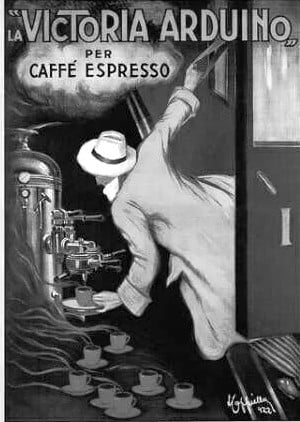

Other Italian inventors such as Pier Teresio Arduino (1876 – 1923), soon produced steam pressure machines capable of spurting out 1,000 cups of espresso in an hour. Even though he conceived of incorporating screw pistons and air pumps into the machines, he was not able to effectively implement his ideas.

Instead, his main contributions to the history of espresso are of a different nature. Arduino was a businessman and master marketer – more so than even Pavoni. He built a marketing machine around espresso, which included directing graphic designer Leonetto Cappiello to create the famous espresso poster that perfectly captured the nature of espresso and the speed of the modern era.

In the 1920s, Arduino had a much larger workshop than Pavoni’s in Milan and, as a result of his production capabilities and marketing savvy, was largely responsible for exporting machines out of Milan and spreading espresso machines across the rest of Europe.

The new espresso machines were designed to dazzle through their size and speed, with rumbling boilers, brass fittings, enameled ornaments, vulcanized rubber knobs, and gleaming metallic lines all at the command of the caffeinated double of the train conductor-engineer-the barista…

And even if the steam-brewed coffee that these behemoths turned out often tasted burnt, the brew was power-packed, intense, and quickly consumed, writes Jeffrey Schnapp.

Espresso ex machina

Italian lexicographer Alfredo Panzini’s dictionary uses first espresso as a term relating to coffee, and was rendered in 1931 as:

Caffè espresso, made using a pressurized machine, or a filter, now commonplace.

The word express was associated with express messengers who could be counted upon to deliver messages at speeds superior to those of the ordinary mail service. This meaning was modified by the rise in mid-nineteenth-century England of special trains running “expressly” to single locations without making intervening stops, trains that soon came to be known throughout Europe as expresses.

The three main features that define espresso are:

- On the spur of the moment: the brew must be prepared just before serving it – express

- In a short time: brewing must be fast

- Under pressure: mechanical energy must be spent within the coffee cake.

As electricity replaced gas and Art Deco replaced the chrome-and-brass aesthetic of the early 20th century, the machines became smaller and more efficient, but no coffee innovators managed to create a machine that could brew with more than 1.5-2 bars of pressure without burning the coffee.

Espresso Revolution: Achille Gaggias’ Crema caffè

Gaggia once complained about the steamy machines with:

“Quando si beveva un caffè, sembrava di entrare in una Milano nebbiosa!”

“Drinking a coffee was like entering a cloudy Milan!”

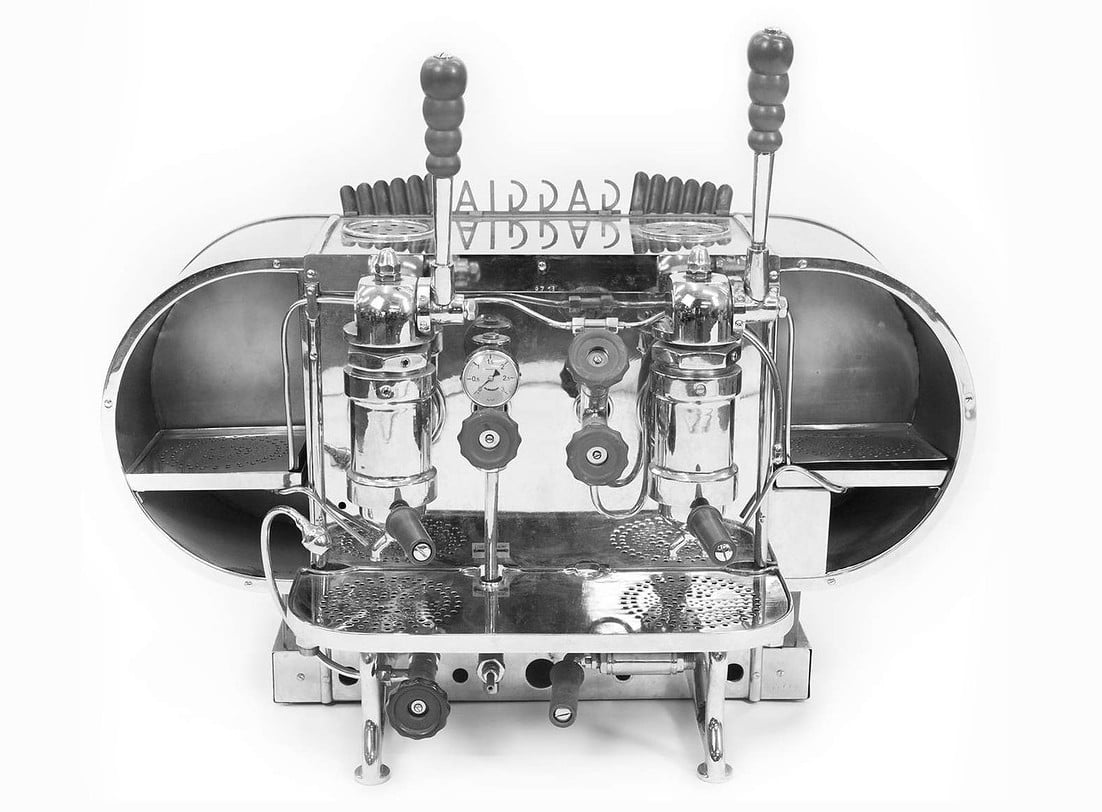

The modern Espresso era begun, when Achille Gaggia (1895–1961), son of local Milanese bar owner, developed first the “a torchio” system in 1936, and renamed it “Lampo” in 1938. This disruptive mechanism used hot water pressure instead of steam and prepared a delicious espresso, characterized by a soft layer of “crema naturale”. A true innovation!

To promote the new dispensing group for coffee crema, Gaggia exhibited “Lampo” at the 1939 Fiera Campionaria (Samples Fair) in Milan. Gaggia’s aim was to sell the new groups to the bars owners, to substitute the ones on old coffee machines.

Unfortunately, the idea was not easy to implement: the only solution was to produce coffee machines that already carried that innovative system.

Achille Gaggia applied for his second patent for the “lever-piston ” in 1947. Legend has it, that the piston engine of an American Army’s jeep that used a hydraulic system inspired him. The piston significantly increased the water pressure, from 1.5 – 2 bar to 8 -14 bar, while also giving out precisely one ounce of water (about 28 ml).

The new Bar- espresso machines produced a great espresso with a thick crema in 1948, when Gaggia asked Ernesto Valente, proprietor of the Faema light engineering company, to manufacture the machine.

Both entrepreneurs, founded “Officine Faema Brevetti Gaggia”, and could produce the first espresso machine: Tipo Classica. It was a technological and aesthetic revolution: horizontally developed, with levers and a shape that allowed the set of more than one group in a row. The steam-free macchina a leva which improved the extraction by decreasing its temperature and elevating the pressure exerted on the coffee grounds, resulting in a more full-bodied and coffee with crema.

Simple to operate by hand, this machine would force hot water, drawn directly from the boiler, through the coffee puck. The use of the piston meant that brewing now took place under much higher pressures, rising and falling from three to twelve atmospheres of pressure during the extraction. This resulted in essential oils and colloids from the coffee creating a mousse or crema on top of the espresso. The resulting liquor extracted considerable flavor from the coffee, was less bitter and delivered in about fifteen seconds.

The slogan on the Gaggia machine was:

“Crema caffè naturale” and “It works without steam”

Today crema (the word has passed into English) is seen as the defining sensory characteristic of espresso; however at the time the new beverage was renamed crema caffè, cream coffee, in order to distinguish it from the extractions produced by the pre-existing espresso machines, like the Moka express or Napoletana for home use.

Guiseppe e Bruno Bambi – La Marzocco

Giuseppe Bambi owns a small machining workshop; Mr. Ascanio Galletti, an entrepreneur, commissions him the production of a 2-group, vertical boiler espresso machine, the Fiorenza.

Even though Mr. Galletti renounces to the commercialization of these machines, Giuseppe Bambi decides to form a partnership with his brother Bruno to produce their own model. Together, they establish Officine Fratelli Bambi in Florence 1927.

La Marzocco is born, named after the lion symbol of Florence.

The period of war caused significant deadlocks for some great ideas.

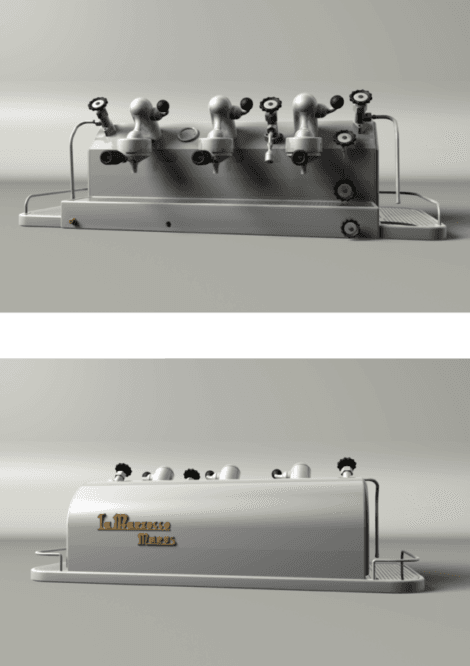

As the Second World War began in 1939, Guiseppe Bambi, applied for a patent for the horizontal boiler design.

In addition to the apparent ergonomic improvements for baristas working behind the bar, the horizontal boiler also offers a significantly larger surface area for placing the cup warmer.

“The most important development before the lever espresso machine was that the espresso machine was not vertical but horizontal, as they kept the heat on the coffee machine. This is very important to keep the cups warm.”

Enrico Maltoni, author and collector of coffee machines, books and patents.

Over the next decade innovations within the industry took place at a remarkable rate as manufacturers attempted to appropriate and improve the new technology. Nearly all of the leading companies were based in or around Milan where ideas, components and personnel flowed between the various workshops.

La Marzocco launched Accademia del Caffè Espresso, a cultural hub, research facility, interactive archive, and international visitors center housed in the company’s original mid-century headquarters, high above the city of Florence.

Giuseppe Cimbali – LaCimbali

In the ‘30s Giuseppe Cimbali, who for twenty years had managed a workshop for processing copper and producing components, including boilers, bought S.I.T.I., which specialized in the production of espresso coffee machines.

This led to the foundation of Ditta Giuseppe Cimbali: copper constructions, coffee machines and soda carbonators.

The company first created La Rapida, a column-style model, followed by Albadoro, one of the first horizontal machine models, which was more efficient from an ergonomic point of view.

In 1950 he invented Gioiello, which featured lever technology that enabled the production of a real espresso with cream.

The company gave the resultant espresso with crema a new name – Cimbalino.

A name that soon became, thanks to a marketing strategy that was well ahead of its time, the way to ask for an espresso coffee at some bars.

A coffee with a fine crema, without air bubbles or white spots, or the tendency to open up to give you a glimpse of the underlying liquid.

Rhymes alternated with irreverent ads. The cimbali were featured in short films, targeted sponsorship in the sports and entertainment world.

The cimbali espresso machines and the word cimbalino for espresso were soon exported internationally. In Portugal you can still say “un cimbalino” when ordering an espresso at the bar, while in Austria and Australia there are still cafés called “Cimbalino”.

MUMAC, Cimbali Group’s Coffee Machine Museum, is a permanent institution open to the public, which holds, preserves, enhances and promotes the study and awareness of its collections in order to spread knowledge of the history and evolution of professional espresso coffee machines and coffee culture.

Francesco Illy – Illycaffè

Francesco Illy (1892 – 1956) founded illycaffè roastery in Triest, in 1933. In 1935 he registered the Illetta, a machine that employed compressed air to generate the pressure for the coffee extraction process.

Also his innovative method of packaging, based on pressurization, enabled illy’s initial exports to Sweden and Holland during the 1940s. Francesco Illy’s method remains the standard for preserving and enhancing coffee’s freshness during transport and storage.

In the 1950s, he spear-headed the company expansion into homes, selling smaller cans of ground coffee for the first time. In 1974, Dr. Illy furthered the company’s lead in coffee innovation with ESE, the first pre-measured espresso pods, making café-quality espresso simple and easy at home or the bar.

In 1988, illy introduced and patented a photo-chromatic means to identify the highest quality beans, one by one. Illy coffees are blended from arabica beans from multiple sources (Brazil, Colombia and India). The grounds are packaged in steel canisters and pressurized with an inert gas rather than air.

With a mission to spread coffee culture around the world and share knowledge to improve quality, in 1999 l’ Università del Caffè (the University of Coffee), was established. It holds courses for baristas, coffee producers and coffee bar managers.

Illy also was one of the first companies to marry art and espresso. The idea to re imagine the espresso cup, the tazzina, lead to the creation of Illy’s Art Collection. Matteo Thun, architect and designer, in 1991 created the white illy coffee cup, as the perfect espresso container, with the aim of enhancing the sensations of every sense involved in tasting a great cup of espresso.

Carlo Ernesto Valente – Faema

Carlo Ernesto Valente began manufacturing his own machines with Faema (Italian acronym: Fabbrica Apparecchiature Elettromeccaniche e Affini), after disagreeing with Gaggia over business. Gaggia regarded his machine (and the crema caffè it produced) as a niche product targeted to the high end of the market, whereas Valente wanted to expand the market for espresso by designing cheaper machines.

In 1961 he came up with the radical innovation of fitting his Faema E61 machine with an electric pump that was operated by a simple on/off switch and replaced the use of the lever.

Furthermore, the E61 optimized the pre-infusion principle: by wetting the ground coffee for a few seconds before starting the delivery, to achieve the maximum extraction of aromatic substances.

The machine was described as “semiautomatic” as it left the barman in control over the length and parameters of the extraction, but did not require him to provide the power for the process. Instead of taking the water from the boiler, the pump drew it directly from the mains, pressurized it, and then passed it through a heat exchanger before it reached the group-head.

This machine was therefore capable of “continuous erogation” in that it could produce one cup of coffee after another without needing to pause to reheat the boiler – making it a genuine “espresso” service. Every single coffee is produced under pressure of 9 atmospheres, the standard today.

The E61s low price facilitated its diffusion, as did the fact that large swathes of Italy were being connected to mains electricity for the first time. Its “pop” styling chimed with the new colorful and informal culture of the 1960s, while the fact that it utilized a horizontal, rather than vertical boiler, meant that operators could now maintain eye contact and conversation with customers while preparing their beverages.

The introduction of machines such as the E61 played a major role in the social and physical reconfiguration of the coffee bar and the role of the barista, that took place in the 1960s, so Morris.

La Marzocco

In 1970, Giuseppe Bambi from La Marzocco developed the Espresso GS, the first two-boiler series, one dedicated to steam extraction (whisking) and the other for extraction — one for brewing coffee, and the other for steaming milk.

GS stands for “Gruppo Saturo” meaning saturated brew group: the group heads, directly connected to the boiler, and designed in a way that enables the water to circulate inside them continuously, maintain the temperature constant, helping to replicate an excellent extraction over and over.

The GS remains the basis for modern espresso machines today.

The E61 and the GS became, and remain, the standard operating machines in Italy, to the point these are now known in the trade as “traditional” Italian Espresso machines.

Beyond the espresso machine

The Italian mechanical industry around coffee includes producers of espresso machines, roasting and packaging equipment, vending machines, and related services.

Italy is the world leader in some of these sectors. Among the most well-known brands are Cimbali-Faema, Astoria-CMA, Brasilia, Gaggia, Wega, La Spaziale, San Marco, Mazzer and Rancilio.

Italian companies control 70 per cent of the global market for commercial espresso machines, routinely exporting over 90 per cent of their output.

Brands like illycaffè and Lavazza – two of Italy’s largest roasters and global suppliers of roasted coffee – helped to cement Italy’s reputation as a key trendsetter for global coffee consumption. Groups such as Illy and Segafredo have established branded chains throughout the world.

Luigi Lavazza

Luigi Lavazza (1859–1949) opened the first Lavazza store in via San Tommaso in Turin in 1895. Luigi studied coffee blending and traveled to Brazil and Africa to develop what would become the signature Lavazza blend.

Luigi Lavazza SpA was founded in 1927 and the unique method of packaging to seal in the coffee’s flavor and aroma was created. Its now world famous logo was created just after WWII and two years later, it patented its version of the coffee tin.

For decades, Lavazza has been the largest coffee producer in Italy. Their coffee is still a blend of Arabica from Brazil and Robusta from Africa.

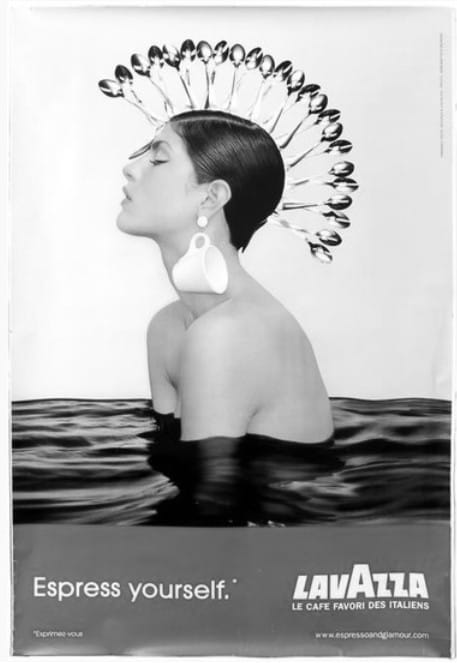

In 1993, the first Lavazza Calendar created by Helmut Newton was produced, signaling the beginning of a close relationship between the Company and the visual arts and featuring fashion photography from some of the world’s leading photographers. The art of advertisement of Lavazza is cult in Italy.

This poster has been created 2003 for the Lavazza Calendar and Campaign by Executive Creative Director – Guido Avigdor, Art Director – Andrea Lantelme,

Photographer – Jean Baptiste Mondino

Lavazza produces capsule coffee machines for homes, offices and large public establishments with coffee vending machines.

In 2000, Lavazza’s collaboration with food philosopher Ferran Adrià revolutionized the world of coffee and launched a new discipline, coffee design.

Coffee brands Made in Italy

Among the key players, Lavazza is by far the biggest roaster and accounts for nearly half of the domestic consumption. Segafredo Zanetti, the leader in out of home consumption, has a smaller overall market share but, if the international operations of the group are taken into consideration, it is notably bigger than Lavazza.

Illycaffè is the leader in the out-of-home, high-quality market segment, with a growing single-serve market share and other important ventures.

Café do Brasil, with the brand Kimbo, is the market leader in southern Italy. There are another twenty medium-sized to large regional companies and a galaxy of small to medium roasters scattered all over the country.

American food manufacturing and processing conglomerate Kraft Foods owns the brand Caffè Splendid, which is second in home market share. Swiss food manufacturing and processing conglomerate Nestlè, including its soluble coffee, is very active in vending and especially in the single-serve capsules market with the worldwide brand Nespresso.

High Tech Coffee

Many specialty roasters program computers to duplicate a “roast profile,” seeking to reproduce a small-batch feel in large (and sometimes small) automated roasters by manipulating the burner, airflow, and drum rotation speed. Utilizing digital technology and easily understood LED screens.

Super-automatic espresso machines allow anyone to create respectable coffee simply by loading the machines with roasted coffee beans and milk. At the push of a button, the machine grinds the beans, tamps the results, pushes hot water through the fine grounds, steams the milk, and all the rest. Some are modest box-shaped devices that sit atop counters in offices, and others are muscular coin-operated devices that wait dutifully in airports and waiting rooms.

There is even an Italian espresso machine on the International Space Station.

Between 2015 and 2017, the first espresso coffee machine (ISSpresso) designed for use in space was produced for the International Space Station by Argotec, Lavazza and the Italian Space Agency (ASI).

Espresso is more than just a drink in Italy: It is a ritual that is savored and enjoyed

Today espresso is thought of as neither a type of coffee, nor a form of beverage, but as the outcome of an Italian preparation process. Using about fifty beans of roasted coffee, finely ground and putting hot water through them at high pressure, we obtain an elixir, a concentrate where thousands of aromatic compounds burst out, to make espresso unique. Moreover, the sensations it offers does not end in the moment it is tasted, but persists. And so will the Italian coffee culture.

Coffee has become an iconic symbol of Italys’ table culture. Italian espresso has become closely identified with the country by both Italians and foreigners alike as have other coffee based beverages like cappuccino macchiato and other delicacies.

Espresso coffee has become a symbol of Italy in the world, representing not only the quality and taste of coffee, but also Italian culture and hospitality. All over the world, Italian cafés and bars have become a meeting and socializing place for people, an opportunity to discover and experience Italian culture and dolce vita.

Thank you for the espresso Luigi Bezzera, Desiderio Pavoni, Pier Teresio Arduino, Achille Gaggia, Guiseppe e Bruno Bambi, Giuseppe Cimbali, Francesco Illy e Carlo Ernesto Valente and many more unnamed creative minds that were involved in forging the coffee story of “Made in Italy”!

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

The history of coffee is an extraordinary study. If you would like to learn more about it, I heartily recommend the book, All About Coffee, by William Ukers. Written in 1928, it will delight you with detail.

- it.wikiquote.org (https://it.m.wikiquote.org/wiki/Voci_e_gridi_di_venditori_napoletani)

Voci e gridi di venditori napoletani - http://90905.homepagemodules.de/t155f59-Cappuccino-Kapuziner-Melange-oder-wie-jetzt.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caff%C3%A8_sospeso

- https://cn.lamarzocco.com/about/history/

- Allegra World Coffee Portal www.worldcoffeeportal.com

- Artusi Pellegrino. Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well, transl. Murtha Baca and Stephen Sartarelli. 2003.

- Biderman Bob. A people’s history of coffee and cafés. 2013.

- Café Culture Magazine www.cafeculturemagazine.co.uk

- Carosello Bialetti: la caffettiera diventa mito https://www.famigliacristiana.it/video/carosello-bialetti-moka-mito.aspx

- Cociancich Maurizio. Storia dell’ espresso nell’Italia e nel mondo. 100% Espresso Italiano. 2008.

- Coffee Review www.coffeereview.com

- Comunicaffe International www.comunicaffe.com

- Davids Kenneth. Espresso Ultimate Coffee. 2001.

- De Crescenzo Luciano. Caffè sospeso. Saggezza quotidiana in piccoli sorsi. 2010.

- De Crescenzo. Luciano. Il caffè sospeso.

- Eco Umberto. “La Cuccuma maledetta” in Agostino Narizzano, Caffè: Altre cose semplici. 1989.

- Global Coffee Report www.gcrmag.com

- Gusman Alessandro. Antropologia dell’olfatto. 2004.

- Hippolyte Taine, wrote in, Italy: Florence and Venice, trans J. Durand. 1869.

- https://www.italienaren.org/tradizioni-italiane-caffe-in-ginocchio/

- http://www.archiviograficaitaliana.com/project/322/illycaff

- http://www.baristo.university/userfiles/PDF/INEI-M60-ENG-Public-Regulation-EICH-v4-1.pdf

- http://www.coffeetasters.org/newsletter/en/index.php/category/a-baristas-life/

- http://www.coffeetasters.org/newsletter/it/index.php/il-galateo-del-caffe/01524/

- http://www.culturaacolori.it/fascismo-contro-le-parole-straniere/

- http://www.espressoitaliano.org/en/The-Certified-Italian-Espresso.html

- http://www.inei.coffee/en/Welcome.html

- https://archiviostorico.fondazionefiera.it/entita/585-bialetti-industrie

- https://bialettistory.com/

- https://cdn.intechopen.com/pdfs/55623.pdf Severini Carla. Derossi Antonio. Ricci Ilde. Fiore Anna Giuseppina. Caporizzi Rossella. How Much Caffeine in Coffee Cup? Effects of Processing Operations, Extraction Methods and Variables

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drip_coffee#Cafeti%C3%A8re_du_Belloy

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ISSpresso

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Italian_meal_structure

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neapolitan_flip_coffee_pot

- https://hal.science/hal-00618977/document

- https://hub.jhu.edu/magazine/2023/spring/jonathan-morris-coffee-expert/

- https://ineedcoffee.com/the-story-of-the-bialetti-moka-express/

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caff%C3%A8

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caff%C3%A8#Risvolti_etici_e_sociali

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napoletana

- https://italofonia.info/la-politica-linguistica-del-fascismo-e-la-guerra-ai-barbarismi/

- https://italysegreta.com/italian-hospitality-the-invite/

- https://library.ucdavis.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/LangPrize-2017-ElizabethChan-Project.pdf

- https://memoriediangelina.com/2009/08/11/italian-food-culture-a-primer/

- https://mostre.cab.unipd.it/marsili/en/130/the-everyday-eighteenth-century

- https://napoliparlando.altervista.org/cuccumella-la-caffettiera-napoletana/

- https://specialcoffeeitaly.com/barista-espresso-coffee-machine/

- https://specialcoffeeitaly.com/italian-breakfast-cappuccino-cornetto/?_gl=1*1gjfoya*_ga*OTE0MDM2ODM5LjE2OTMzNjE5OTg.*_ga_2HTE5ZB0JS*MTY5MzM2MTk5Ny4xLjEuMTY5MzM2Mjk0NS4wLjAuMA../

- https://specialcoffeeitaly.com/what-came-first-the-italian-bar-or-coffee/

- https://themokasound.com/

- https://uwyoextension.org/uwnutrition/newsletters/understanding-different-coffee-roasts/

- https://www.adir.unifi.it/rivista/1999/lenzi/cap2.htm

- https://www.bialetti.co.nz/blogs/making-great-coffee/using-bialetti-coffee-makers

- https://www.bialetti.com/ee_au/our-history?___store=ee_au&___from_store=ee_en

- https://www.bialetti.com/it_en/inspiration/post/ground-coffee-for-moka-should-never-be-pressed

- https://www.brepolsonline.net/doi/pdf/10.1484/J.FOOD.1.102222

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/Amsterdam/2014.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/Amsterdam/2014.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/Milan/2013/Gallery/Other/Amalia-Chieco

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/NewYork/2016.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/NewYork/2017.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/NewYork/2018.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/NewYork/2019.aspx

- https://www.coffeeresearch.org/science/aromamain.htm

- https://www.coffeereview.com/coffee-reference/from-crop-to-cup/serving/milk-and-sugar/

- https://www.comitcaf.it/

- https://www.ecf-coffee.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/European-Coffee-Report-2022-2023.pdf

- https://www.espressoitalianotradizionale.it/

- https://www.euronews.com/culture/2022/02/15/the-italian-espresso-makes-a-bid-for-unesco-immortality

- https://www.faema.com/int-en/product/E61/A1352IILI999A/e61-legend

- https://www.finestresullarte.info/en/works-and-artists/the-bialetti-moka-the-ultimate-romantic-design-object

- https://www.finestresullarte.info/opere-e-artisti/moka-bialetti-oggetto-design-ultimi-romantici

- https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/leisure/food/2022/02/15/italy-woos-unesco-with-magic-coffee-ritual/

- https://www.gaggia.com/legacy/

- https://www.gamberorossointernational.com/news/coffee-10-false-myths-to-dispel-on-the-beverage-most-loved-by-italians/

- https://www.gcrmag.com/calls-to-review-price-structure-of-italian-espresso/

- https://www.granaidellamemoria.it/index.php/it/archivi/caffe-espresso-italiano-tradizionale

- https://www.illy.com/en-us/coffee/coffee-preparation/how-to-make-moka-coffee

- https://www.illy.com/en-us/coffee/coffee-preparation/how-to-use-neapolitan-coffee-maker

- https://www.ilpost.it/2011/06/08/itabolario-bar-1897/

- https://www.itstuscany.com/en/bar-where-the-word-comes-from/“Cafe Hawelka”, John A. Irvin

- https://www.lastampa.it/verbano-cusio-ossola/2016/02/17/news/le-ceneri-di-renato-bialetti-nella-sua-moka-con-i-baffi-1.36565348/

- https://www.lavazza.com/en/coffee-secrets/neapolitan-coffee-maker

- https://www.lavazzausa.com/en/recipes-and-coffee-hacks/making-espresso-at-home

- https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/third-wave-coffee-meets-tradition-neapolitan-maker-bruno-lopez

- https://www.mumac.it/we-love-coffee-en/be-our-guest-en/progettazione-e-rito/?lang=en

- https://www.quartacaffe.com/images/pdf/carta-dei-valori.pdf

- https://www.repubblica.it/il-gusto/2021/07/26/news/caffe_il_piu_clamoroso_equivoco_gastronomico_d_italia-311835974/

- https://www.taccuinigastrosofici.it/ita/news/contemporanea/semiotica-alimentare/print/Pop-cibo-di-sostanza-e-circostanza.html

- https://www.thehistoryoflondon.co.uk/coffee-houses/

- https://www.wien.gv.at/english/culture-history/viennese-coffee-culture.html

- Illy Andrea. Viani Rinantonio. Furio Suggi Liverani. Espresso Coffee. The Science of Quality. 2005.

- International Coffee Organization www.ico.org

- Kerr Gordon. A Short History of Coffee. 2021.

- La cremina per il caffè: come farla bene. https://www.lacucinaitaliana.it/news/cucina/come-fare-la-cremina-del-caffe/

- Allen Lee Stewart. Devil’s Cup. A History of the World According to Coffee. 1999.

- Leonetto Cappiello – Wikipedia page on the creator of the 1922 poster La Victoria Aduino.

- Markman Ellis. The Coffee House. A Cultural History. 2005.

- Mennell Stephen. All Manners of Food. Eating and Taste in England and France. 1996.

- Montanari Massimo. Il riposo della polpetta e altre storie intorno al cibo. 2011.

- Montanari Massimo. Il sugo della storia. 2018.

- Morris Jonathan. A Short History of Espresso in Italy and the World. Storia dell’espresso nell’Italia e nel mondo. In M. Cociancich. 100% Espresso Italiano. 2008.

- Morris Jonathan. Coffee: A Global History. 2019.

- Morris Jonathan. Making Italian Espresso, Making Espresso Italian.

- National Coffee Association www.ncausa.org

- Pazzaglia Riccardo. Odore di Caffe’. 1999.

- Pendergrast Mark. Uncommon Grounds. The History of Coffee and How It Transformed Our World. 2019.

- Perfect Daily Grind www.perfectdailygrind.com

- Scaffidi Abbate Mario. I gloriosi Caffè storici d’Italia. Fra storia, politica, arte, letteratura, costume, patriottismo e libertà. 2014.

- Schnapp Jeffrey. The Romance of Caffeine and Aluminum. Critical Inquiry. 2001.

- Sibal Vatika. Food: Identity of culture and religion. 2018.

- Specialty Coffee Association www.sca.coffee

- Spieler Marlena. A Taste of Naples. 2018.

- Tea and Coffee Trade Journal www.teaandcoffee.net

- The Long History of the Espresso Machine. www.smithsonianmag.com

- The Pleasures and Pains of Coffee by Honore de Balzac

- The relaxation ritual https://themokasound.com/

- Tucker, Catherine M. Coffee Culture: Local Experiences, Global Commensality, Society and Cuture 2011.

- World Coffee Research www.worldcoffeeresearch.org