Coffee Culture in Türkiye and in Istanbul is widely present and has deep roots in history, drinking Turkish Coffee, or Türk Kahvesi and eating Lokum with it, is a unique pleasure for the Turks. Coffee is an important part of everyday life and is surrounded by its own special rituals and folklore: equipment, ceremonies– like fal or fortune read, jokes, stories, sayings and medical uses.

In this Article

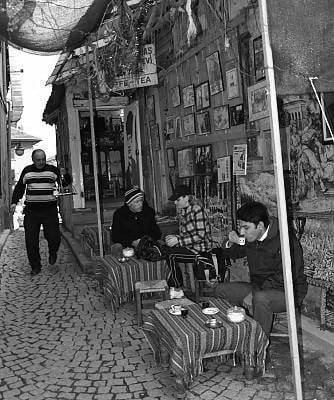

Again we are sitting, in a coffeehouse tucked in a narrow alley near Taksim Square in Istanbul, it is a tiny café that proudly proclaims to serve coffee

“so thick even a water buffalo cannot sink in it”.

That term can be simplified in one Turkish word Mandabatmaz, which incidentally is the name of the café. Mandabatmaz, meaning – the buffalo will not sink.

This name may be given in jest, but its message is no joke. Turkish coffee, Türk Kahvesi is incredibly thick and dense. It is not unusual to hear the local people describe the beverage as:

“black as hell, strong as death, and sweet as love”

anonymous

A tea drinking country like Türkiye has its people fiercely passionate about coffee.

“To us, tea is just a beverage … but coffee? It’s a culture”

Breakfast only ends when coffee is had, although coffee is also consumed at any time of the day. In fact, the Turkish word for breakfast, kahvaltı, literally means “before coffee”, and is derived from the words “kahve” (coffee) and “altı” (before). Also coffee should not be drunk on an empty stomach. There is a reason why Turks call breakfast “kahvaltı”.

“If you cannot find something to eat before coffee, pull off your button and eat it!”

Turkish Coffee Culture means, that no meal ends without a serving of the thick and frothy beverage. A cup of Turkish coffee is endowed with a variety of important connotations for Turks: friendship, affection and sharing. This is best illustrated in the old saying:

“A single cup of coffee can create a friendship that lasts for 40 years”.

Although tea is replacing coffee in daily life, the saying of

“drinking someone’s coffee”

is considered to be the start of peoples to marriage.

Wedding rituals and Turkish Coffee

When decided on wedding one week before the engagement ceremony, coffee and Lokum, a small piece of soft sugar dusted candy with a gummy texture, are offered to the guests. These are also brought to the house of the groom to be, in the morning of the ceremony.

On the other hand, when people visit the house of the wife to be, she prepares coffee for the guests and the fact that she prepares coffee with a great deal of foam is an indication of how skillful she is.

Salted coffee, darling?

There’s another traditional practice for this ceremony, the wife to be puts salt, instead of sugar, into the coffee for her future husband and expects him to drink it without complaining. If he drinks the salty coffee without a fuss, then it is a sure sign of unconditional love.

I have heard that if a wife makes bad coffee, that is grounds for divorce.

Coffee grew very important in Ottoman times to the point it became legal for a woman to divorce her husband if he failed to provide her with her daily quota of coffee.

Traditional turkish coffee in cezve prepared on hot sand. Cups stay warm, and the heat used for brewing can be adjusted by the depth of the coffee in the sand.

Savoring Coffee Culture in Istanbul

To drink a coffee in Istanbul (Constantinople) is a deeply cultural process that invites to delve in history of the Ottoman Empire, folklore and legends about Coffee. We sit down, take our time and just enjoy, slowly and carefully. To avoid drinking the grounds, we stop drinking when about one fifth of the coffee remains.

Proper Turkish coffee, or Türk Kahvesi is a thick, strong brew with a layer of grounds settled at the bottom – these days it’s usually prepared by boiling the fine grind coffee, water and sugar together in a copper pot, called Cezve, Kanakas or Ibriks, on a stove top, though the traditional method is by heating it in sand and coals. The cezve are representative of the earliest known vessels for making coffee. The beverage was brought to boil and cooled at least two or three times before being served. The folding handle made it easier to carry the Ibrik on the back of a camel.

The ritual of making or ordering Türk kahvesi starts immediately as we have to declare our preferred level of sweetness:

- şekerli sweet

- orta şekerli medium sweet

- az şekerli a little sugar

- sade which means no sugar

We also have to choose if we want it flavored with cardamom, cinnamon, mastic, anise or clove. “Tartar” coffee is with heavy cream, and “kervansaray” with carob (St John’s-bread, or locust bean). In Ottoman times the drink was served thick, bitter, and near-boiling, with no sugar. Cardamom was the only spice added with any frequency, although in some disreputable quarters opium and hashish apparently were also stirred in. The Ottoman coffeehouses used to enhance it with the aroma of exotic spices like saffron and even ambergris (dried whale vomit).

Traditionally people were drinking Türk Kahvesi without any sugar, unsweetened coffee is called “country style” or “man’s coffee”, also today.

“Kahve, lütfen” are the magic words, and the frothy kahvesi arrives.

The Preparation of Türk Kahvesi

There are many stories about how coffee was first discovered – Turkey lays claim to having the world’s oldest method of preparing it.

Crafting of Turkish coffee, however, evolved over time to what we are tasting now. Though each individual kahvıcabşır (master craftsman) has added his own twist to the process, the fundamentals tend to be:

100% Arabica beans are roasted and then very finely ground; the grains for Turkish coffee are finer than they are for espresso.

İzzet, our kahvıcabşır, will measure one pretty heaped spoonful of this finely ground coffee directly into the Cezve, a little copper pan, the inside covered in silver, with a long handle, then he will add the sugar and the right amount of cold water. He puts the pan on the gas and then stirs it once with a wooden spoon.

The preparation of Turkish Coffee requires the close personal attention of the preparer because if the coffee is allowed to boil over it will lose it’s foam. Türk kahvesi shall never boil. As the foam will create a ring at the edges of the pot, he lowers the heat, the foam will close and rise upwards. Quickly İzzet removes the cezve from the gas, waits a few seconds and shares out the frothy foam into the waiting cup. Now he replaces it on the gas for a “second rise”. When the coffee froths once again, the Türk kahvesi is ready to be served.

“TÜRK KAHVESİ BOL KÖPÜKLÜ OLURSA USTUNDE DEVE YÜRÜMELİ.”

The foam of the Turkish coffee is so thick a camel can walk across it.

The service of coffee was, and remains, perhaps as significant as the preparation. The elements of service have changed little over the course of its history.

İzzet, comes with a small tray in his hands, and says:

“ Give the sediment time to settle down in its cup before you take your first sip. Right before you drink, you have to clean your throat with water. When you are finished drinking, you can eat a Turkish delight, Lokum to sweeten your mouth.

Watch the froth, the mark of a good cup of coffee lies in the rich foamy top!”

Lokum is a small piece of soft sugar dusted candy with a gummy texture.

With this words, he places the rich decorated tray on the table and leaves us with this delicacy. My Türk kahvesi with cardamom is hidden in a porcelain cup with a copper holder and a lid, a glass of cold water and a little plate with several pieces of Turkish delight. There is no spoon, as it would destroy the foam and disturb the sediment. I drink my coffee slowly, savoring the flavors sip by sip; no rushing. The coffee is strong, but not bitter, and its strength is tempered by the sugar.

Kadhi Hodhat, the poet, explains how to take coffee:

As with art it’s prepared, one should drink it with art.

The mere commonplace drinks one absorbs with free heart;

But this—once with care from the bright flame removed,

And the lime set aside that its value has proved—

Take it first in deep droughts, meditative and slow,

Quit it now, now resume, thus imbibe with gusto;

While charming the palate it burns yet enchants,

In the hour of its triumph the virtue it grants

Penetrates every tissue; its powers condense.

Circulate cheering warmths, bring new life to each sense.

From the cauldron profound spiced aromas unseen

Mount to tease and delight your olfactories keen,

The while you inhale with felicity fraught,

The enchanting perfume that a zephyr has brought.

Mark Twain did not know how to drink Türk kahvesi, in “The Innocents Abroad” (1869) , he writes that

“Of all the unchristian beverages that ever passed my lips, Turkish coffee is the worst. The cup is small, it is smeared with grounds; the coffee is black, thick, unsavory of smell, and execrable in taste.”

The story goes on to say,

“The bottom of the cup has a muddy sediment in it half an inch deep. This goes down your throat, and portions of it lodge by the way, and produce a tickling aggravation that keeps you barking and coughing for an hour.”

And finally: a time- honored custom after drinking Türk kahvesi is to place the saucer on top of the cup and then turn the cup over and let it rest. When the grounds have cooled and settled in the cup, you are ready to have your fal or fortune read…

İzzet says:

“ When you tell fortunes from the coffee cup, foam has an important role. The tiny bubbles in the foam are interpreted as the evil eye.

There must be enough coffee grounds at the bottom for the fortune-telling. In my culture, if the ground amount is not enough for fortune-telling, the coffee is considered of low quality.”

Over the course of our stay in his coffeehouse, İzzet wove in countless interesting stories.

Lokum

In order to overcome coffees bitter taste people started offering their guests a small sweet called lokum. The basic ingredients of Turkish delight are corn starch, caster sugar and various oils and flavorings along with dried fruits or nuts.

According to the Frenchman Pretextat-Lecomte, who observed the process in the late 19th century, the secret of authentic lokum lies in stirring the mixture “in the same direction, and without interruption” for “approximately two hours”. Two men, he noted, took turns. Only this traditional method, results in a gradually melting delight as it soothes its way towards ones throat, slowly releasing a heavenly mix of flavors from the oils and fruits.

Sophisticated and expensive ingredients, such as musk and rose were added, traditionally rosewater and orange blossom water flavored Turkish delight, too. The locals choice of delight are layered with crushed nuts, most popular being roasted pistachios, hazelnuts and coconut flakes added into the mixture and rolled layer by layer.

Most popular Turkish delight flavors are rose, lemon, orange, pomegranate, mint, mastic, pistachio, hazelnut, walnut and cream. More recently chocolate covers Turkish delight as well as coffee.

The first appearance of Turkish delight started in 1776 by Bekir Efendi. As legend goes, the Ottoman Sultan, trying to cope with all his harem ladies, summoned his confectionery chefs and demanded the production of a unique sweet.

It is also told, that another Ottoman Sultan angrily summoned his Şekercibaşı, chef pâtissier, in the Imperial kitchens at Topkaı Palace and ordered him to concoct a delicacy that was sweet, soothed the throat and not hard on his tooth upon chipping his tooth on hard candy.

Another story states that it was Bekir Efendi, later titled Hacı Bekir following the completion of his pilgrim duties, invented Turkish Delight and went on to open a little shop in the city center of Constantinople. Quickly winning fame and fortune amongst a people with quite the sweet tooth. Turkish Delight became a fashionable gift, and rose to become an object used in the act of courting, wrapped in special, lace handkerchiefs. It was no surprise that Bekir Efendi was appointed chief confectioner to the Ottoman Court.

Turkish Delight is made from a sugar syrup and starch milk mixture that is cooked for five to six hours, at which point the flavor is added. The mixture is then poured into large wooden trays to be set and about five hours later they are rolled, cut and dusted with icing.

Manufacturing lokum became the first big businesses with close relation to Turkish coffee. Later coffee pot making and porcelain cups established their trademarks in Turkish coffee business.

UYKU YORGANSIZ KAHVE DUMANSIZ OLMAZ. DUMANSIZ KAHVE IMANSIZ TÜRK’E BENZER.”

Sleep cannot be without a blanket, coffee and smoke coffee without smoke is like a Turk without faith.

Never turn down a coffee in Turkey

Coffee has a distinctive place at the hospitality of Turkish people, if invited to have coffee, you have to accept, as it is considered rude to turn down the offer. That’s how serious they are about coffee in Turkey.

When thinking of the word hospitality, what comes to mind is a Turkish “abla” or “teyze,” ushering me into her home, giving me slippers from their collection or even taking the shoes off her own very feet to make sure mine are covered.

Leyla Yvonne Ergil

Then I imagine entering an impeccably clean home, being given a cup of freshly brewed tea or Turkish coffee and more often than not tidbits that include the usual culprits of olives, cheese or nuts.

Türk Kahvesi carries special preparation and brewing techniques. It is one of the oldest coffee making methods still in use. The traditional techniques used in preparing coffee led to development of special tools and silverware such as the boiling pot (cezve), coffee cup (fincan), mortars and hand grinders which have artistic value.

Trying to leave can also be trying, not only will you most likely be bombarded with a bag of something they have picked or collected as a gift, but also a new wave of conversation almost always begins as you try to leave but get stuck chatting with the host between the cracked door.

One thing is certainly true and that is that it is very rare to leave a Turkish home empty-handed. Meanwhile, although always appreciated, as the guest you are not expected to arrive with anything, contrary to Western traditions.

Private coffee culture

The Turkish word selamlık translates to “greeting” and was an area of the household reserved for housing male guests. Historian Defne Çizakça explains,

“Whether rich or poor most households in Istanbul had a special room for accepting guests. It was in this room that dinner and refreshments would be served, politics discussed, intellectual opinions formed.”

The role of the selamlık continued to exist within Ottoman culture and it was transferred from the private household into the public coffeehouse.

Traditionally, women liked to gather around coffee with neighbors and relatives as part of their social routine. Occasionally during those gatherings, fal or fortune telling is practiced.

Fal or fortune read

Because Türk kahvesi is not filtered or strained, as the coffee is consumed, a dark, muddy sediment forms at the cup’s base. The centuries old practice of reading images in leftover coffee grounds, is known as Tasseography.

Once the coffee is finished and the cup has cooled down, it’s turned upside down onto its saucer. The drinker rotates the cup clockwise three times, and lets it cool down a little longer. When the cup is slowly lifted, the fortune teller will read the coffee drinker’s future from the patterns the grains leave on the inside of the cup and saucer.

The “reading” is done by deciphering the images that appear within the coffee grounds. These represent symbols and various omens, both good and bad.

- Ring: Marriage, new love

- Broken ring: Divorce, break-up

- Knife: Break up with a friend

- Bird: Good news

- Raven/Crow: Bad News

- Mountain: Obstacles

- Heart: Love

- Full moon: Love

- Flower: Happiness

- Volcano: Loss of control

- Fish: Career achievement

- Nest: Pregnancy

- Angel: Protection, good news

- Devil: Danger, bad news

- Dog: True friendship

- Cat: Argument, bad friendship

Today the fal is still common in Istanbul and Turkey.

No wonder Coffee culture in Turkey is recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, with so much tradition surrounding it.

It is the preparation and drinking of coffee that became an art form in Turkey and spread across many parts of the world with the Ottoman Empire.

The word coffee comes from the Turkish kahve which is in turn derived from the Arabic kahwa قهوة or from the Kaffa Kingdom – Ethiopia. The beans originally came from Africa (Ethiopia), Arabia (Yemen), over Egypt to the rest of the world.

There are different versions of the story of the introduction of coffee to Turkey but we know it occurred in the 16th century. When the Ottoman coffeehouses opened in Constantinople, it was strongly opposed by the religious leaders who considered coffee to be so dangerous that they declared it sinful – haram, and banned it. But not for long, the people of the ottoman empire loved their coffee, tobacco and coffeehouses.

The Swedish traveler and envoy to the Ottoman Empire, Nicholas Rolamb, in his Relation of a Journey to Constantinople, 1657, describes the important role coffee played in Turkish domestic life:

“This [coffee] is a kind of pea that grows in Egypt, which the Turks pound and boil in water, and take it for pleasure instead of brandy, sipping it through the lips boiling hot, persuading themselves that it consumes catarrhs, and prevents the rising of vapours out of the stomach into the head.

The drinking of this coffee and smoking tobacco (for tho’ the use of tobacco is forbidden on pain of death, yet it is used in Constantinople more than anywhere by men as well as women, tho’ secretly) makes up all the pastime among the Turks, and is the only thing they treat one another with; for which reason all people of distinction have a particular room next their own, built on purpose for it, where there stands a jar of coffee continually boiling.”

From street vendors to grand Coffeehouses

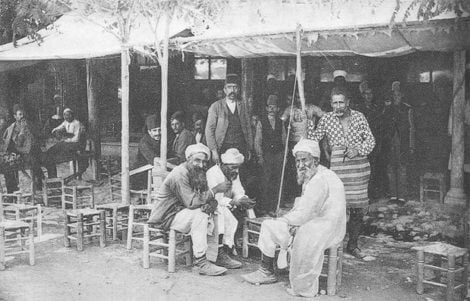

Coffee’s success and integration into Ottoman culture was given by street coffee and coffeehouses. Coffee’s renown soon spread beyond the palace, grand mansions, markets and homes.

Coffee plays a major role in everyday life, whether it’s in the form of “morning coffee” (sabah kahvesi), “pleasure coffee” (keyif kahvesi) or “fatigue coffee” (yorgunluk kahvesi).

Street vendors served meandering locals in markets throughout Constantinople (Istanbul). Customers walked up to the portable booth or coffee was delivered to various places within the bazaar. Within a very short time, Ottoman coffeehouses, or Ottoman Cafés where build in Constantinople and the Sultan used to build them in the whole empire.

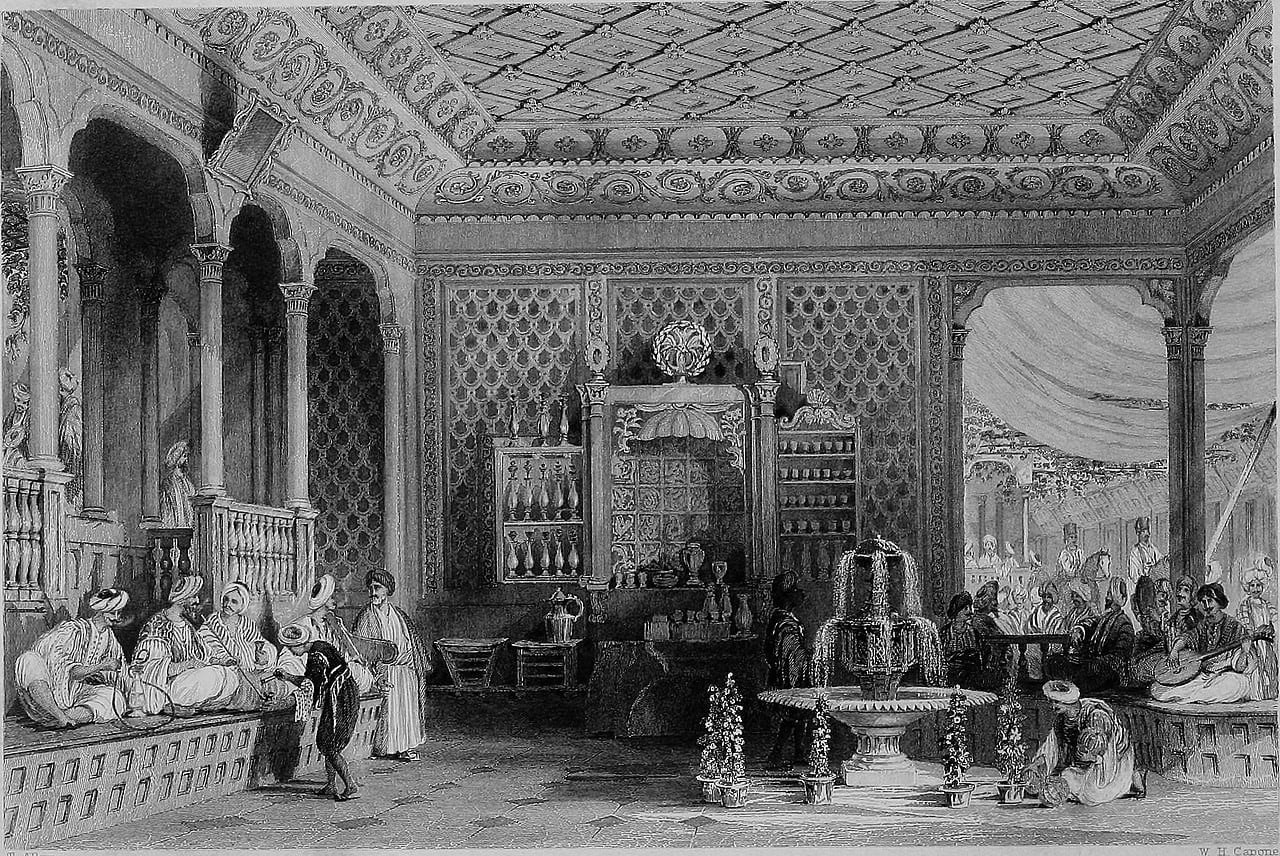

This grand coffeehouses were gentlemen clubs with fine views, pavilions, fountains, and pools where men could relax, smoke their pipes, listen to music, storytellers, and discuss business, politics, arts and more.

This engraving shows the intricate interior of a grand coffeehouse, with the “Yasmaklı coffee oven”, where the Türk Kahvesi was prepared. Ottoman Coffeehouses were square-shaped and surrounded by large sofas on three sides called “peyke.” Clients took off their shoes and sat on the peykes. Thus, these verses were written on the walls of the coffee houses:

“The heart desires neither coffee nor coffeehouse

The heart only desires companionship, coffee is only the excuse.”

“There were also Tabacco and opium smokers’ coffee houses and public storytellers’ (Medda) coffee houses, as well as coffee houses for aşıklar — the folk poets and musicians of Turkish oral culture. Sometimes a barber would sit next to the coffee hearth so you could get a shave there as well,” art historian Cicek Akcil, comments.

“The janissary coffeehouses often had Greek dancers for entertainment and also attractive young boys serving the customers.”Ottoman coffeehouses are designed so that people can have a talk with each other, to play and to dream…

“Well that’s about it: you never considered getting rich nor surrendering to the will of fate, nor anything else.

You now know that all your dreams – even the wilder dreams of your youth – were nothing more than the aroma of coffee drifting out of some coffeehouse in a tiny neighborhood.”

~ Demir Özlü, Gezintiler II (Excursions II)

Coffeehouses in Constantinople serve Coffee, that remains a central and popular drink in many different places all over Türkiye.

In restaurants, clubs, theaters, universities, salons and most importantly inside every home it is there: as a token of cultural heritage and history .

The tradition of drinking coffee permeates all walks of life in the coffeehouse and at home. Celebrated in literature and songs, Turkish coffee is a symbol of friendship, hospitality and refinement. It plays a key role in social occasions such as engagement ceremonies and holidays. In his writings Sheik Abd-al-Kadir states:

“No one can understand the truth until he drinks of coffee’s frothy goodness.”

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

The history of coffee is an extraordinary study. If you would like to learn more about it, we heartily recommend the book, All About Coffee, by William Ukers. Written in 1928, it is as good a book on coffee as has been written and will delight you with detail. Also the new book Short History of Coffee, by Kerr Gordon is delightful.

Thank you Klaus for proofreading and sharing your knowledge about culture in Turkey.

- From Kaffa to Istanbul: Coffee’s journey to Turkey.

- Illustrations Wikimedia

- Kerr Gordon. Short History of Coffee. 2021.

- Kucukkomurler Saime, Ozgen Leyla. Coffee and Turkish Coffee Culture. Article in Pakistan Journal of Nutrition. 2009.

- Nair Sharmila. Turkish coffee, a 500-year-old tradition.In: Food News. 2015.

- Sansal Burak. Turkish coffee. All About Turkey.

- Turkish coffee culture and tradition. UNESCO.

- The Turkish Coffee Culture and Research Association.

- Ukers W. H. All About Coffee. The tea and coffee trade journal.1922.

- Wild Anthony. Black Gold: A Dark History of Coffee. 2005.

- Wilson Georgia. Drinkable history: the 500-year-old method to making coffee. 2014.