The term “coffee” refers to the plant, the drink and the place where it is served. Caffeine has been used as a medicinal and recreational drug since before recorded history, by consumption of caffeine bearing plants.

Ethnobotany is a multidisciplinary science that studies how people traditionally use plants – for food, clothing, shelter and their use for religious ceremonies and health care.

In this Article we will look at historical writings about coffee and how cultures perceive and use the shrub over time.

In this Article

The coffee plant

Illustration of Coffea Arabica (Coffea Arabica L., Arabian coffee) from A supplement to Medical botany by William Woodville. 1794.

Public domain, edited.

Coffee is the evergreen tree in the genus of Coffea of the Rubisceae plant family. There are two species from which all the others derive:

“Coffea Arabica Linné” or Arabica, the oldest, it represents 70% of world production.

“Coffae Canephora Pierre” or Robusta is more resistant to heat and disease, which offers a full-bodied and powerful, but less fragrant coffee.

Arabica is considered to having better flavor and aroma, however, Robusta seeds contain more caffeine.

Caffeine (Methylxanthine)

The caffeine in coffee plants, (seeds and leaves) protects it from insect herbivory.

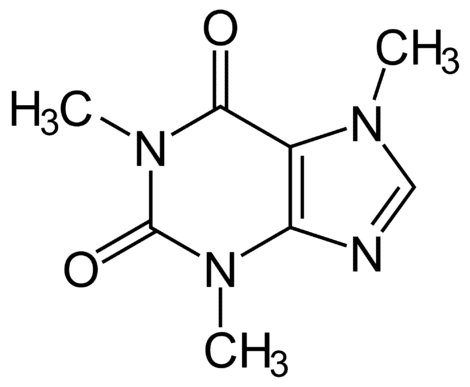

Caffeine is a compound that naturally occurs in coffee plants, it is alkaloid in nature and its chemical name is 1, 3, 7-trimethylxanthine (C8H10N4O2). Caffeine is most associated with coffee and was first isolated from the coffee bean and documented by Ferdinand Runge in 1819. Runge called Caffeine “Kaffebase”, meaning a foundation that exists in coffee.

In 1827, M. Oudry discovered a chemical in tea he called “thein,” which he assumed to be a different agent but that was proven in 1838 by Gerardus Johannes Mulder and Carl Jobst, that theine was actually caffeine. Pure caffeine is a bitter, highly toxic white powder, readily soluble in boiling water. It is classified as a central nervous system stimulant and a drug that restores strength and vigor.

After caffeine is ingested, it is quickly and completely absorbed into the bloodstream, which distributes it throughout the body. The concentration of caffeine in the blood reaches its peak thirty to sixty minutes after it is consumed.

The presence of the bitter alkaloid in the coffee stimulates certain portions of the nervous system.

In Uncommon Grounds : the History of Coffee and How It Transformed Our World, Pendergrast Mark writes: Humans clearly crave stimulating concoctions, drinking, chewing, or smoking some form of drug in virtually every culture in the form of alcohol, coca leaves, kava, marijuana, poppies, mushrooms, qat, betel nuts, tobacco, coffee, kola nuts, yoco bark, guayusa leaves, yaupon leaves (cassina), maté, guaraná nuts, cacao (chocolate), or tea.

Of those in the list above, caffeine is certainly the most ubiquitous, appearing in the last nine items. Indeed, caffeine is produced by more than sixty plants, although coffee beans provide about 54 percent of the world’s jolt, followed by tea and caffeinated soft drinks.

Caffeine is one of the most consumed psychoactive substances on the earth and is known for its stimulating effects.

Public domain.

Further research has indicated that it can reduce physical fatigue and prevent or treat drowsiness. It produces increased wakefulness and focus, as well as better general body coordination.

When we drink a cup of coffee, caffeine is rapidly absorbed by our bodies and starts to take effect within minutes. In the brain, caffeine blocks the action of the neurotransmitter adenosine, which is responsible for inducing feelings of fatigue and drowsiness.

By blocking adenosine, caffeine allows other neurotransmitters, such as dopamine and norepinephrine, to increase their activity in the brain. These neurotransmitters are associated with feelings of pleasure, well-being, and alertness, resulting in an improved mood and better spirits.

Black coffee is concentrated sunshine.

This sentiment is often credited to Alexander von Humboldt (1769 –1859). However, in an 1836 letter to Heinrich Christian Schumacher von Humboldt (1780 – 1850) credited, the old Delisle – French cartographer Guillaume Delisle (1675 – 1726) ? – as singing a half cup of black coffee is “concentrirte Sonnenstrahlen” or concentrated sunbeam.

The observed physiological effects of caffeine feels more of a wake-up than the sunrise itself and can include enhanced problem solving, improved logical reasoning, rapid information processing, and improved cognitive function.

The majority of medical research to explore the effects of coffee on health has focused on caffeine. But caffeine is only one of the pharmacological active compounds in coffee that may influence human health.

Coffees Chemical Complexity

The roasted coffee bean contains a complex combination of compounds – oils, caramels, carbohydrates, proteins, phosphates, minerals, volatile acids, nonvolatile acids, ash, trigonelline, phenolics, volatile carbonyls, and sulfides – making it a complex food product.

Molecules with biological activity are present in coffee beans, as well as in the pulp and leaves of the plant, contributing richly to popular medicine for the treatment of many diseases.

Recent scientific reports confirm that consuming coffee could help reduce risk of stroke, diabetes, digestive diseases, gout, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson, liver cancer, colon cancer, and prostate cancer. One of the main compounds, caffeine is known to act on the central nervous system, as well as having effects on the cardiovascular system.

Catherine M. Tucker, writes about the Chemical Complexity of coffee, in Coffee Culture: Local Experiences, Global Connections. 2017:

Coffee contains more than 1,000 different chemical compounds; around 800 are volatile chemicals that dissipate rapidly. Arabica and Robusta coffees have important differences in their chemical composition. Coffee’s rich aroma results from the mixture of about 50–60 volatile chemicals released during brewing. Decaffeinated coffee appears to reduce the risk of lung cancer among smokers, but not regular coffee.

Coffee’s chemical complexity has complicated research efforts, and many uncertainties persist about its physiological effects.

Variations in blending, roasting, and brewing lead to differences in the chemical composition of the coffee, which can be difficult to evaluate or control. In addition, few studies account for differences in how strongly people brew their coffee, or the amounts of sugar, milk, etc that may be added.

The differences in coffee blends, roasts, brewing methods, and individual additions make it challenging for medical research to explore the effects of coffee on health and account for and examine all of the variables.

Only one thing is certain about coffee, though. Wherever it is grown, sold, brewed, and consumed, there will be lively controversy, strong opinions, and good conversation.

The best stories [are told] over coffee

anonymous

Ethiopia

Coffee is first used by Ethiopia’s Galla tribe who noticed the energy they felt after eating the berries.

Ethiopia is considered to be the birthplace of the coffee plant and of coffee culture. Ethiopian tribesmen crushed up the whole ripe berry, including the hulls and coffee beans, and then mixed it with animal fat to make round food balls. They carried this balls on journeys for nutrition and stimulation. The coffee berries were also placed in cold water and left to soak much like sun tea is made today. Some researchers think that people first made an alcoholic beverage from coffee seeds and that the non-alcoholic beverage came later.

From the Coffee ceremonies in Ethiopia, as a cornerstone of hospitality and social occasion to connect with friends and family, coffee is now loved worldwide. In many cultures, inviting someone for coffee is seen as a gesture of hospitality and friendship. This age-old tradition has the power to bring people from different backgrounds and lifestyles together, breaking cultural barriers and creating a sense of belonging to a global community.

Coffee as Materia Medica: An ethnomedicinal and historical perspective

The origins of coffee are steeped in legend and topped with a creamy dollop of speculation.

The first written references of Coffee from Arabia

The first mention of coffee in print appears in the writings of the Persian polymath and physician, Abū Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariyya al-Razi (854-925 AD), known also as Rhazes. He wrote 200 books on medicine, surgery theology, mathematics and astronomy, but his principal work is Al-Haiwi, or The Continent, the encyclopedia of Greek, pre-Islamic Arab, Indian and even Chinese medical knowledge.

The merit of this attribution depends on the meaning, in Rhazes’ time, of the Arabic words “bumz” and “buncham.” Across the sea in Abyssinia these words referred, respectively, to the coffee seed and the drink, and they still have these meanings there today. In his lost medical textbook, AI-Haiwi (The Continent), Rhazes describes the nature and effects of a plant named “bmm” and a beverage named “buncham or bunchum, describing it as

“hot and dry and very good for the stomach”.

However, the oldest document referring to buncham is the monumental classic discourse The Canon of Medicine (AI-Gnmmz fit-Tebb), written by Avicenna (980-1037) at the turn of the eleventh century.

The fifth and final part of his book is a pharmacopoeia, a manual for compounding and preparing medicines, listing more than 760 drugs, which includes an entry for bunchum. In the Latin translation made in the twelfth century, this entry reads in part,

“Bunchum quid est? Est res delatade Iamen.

Quidam autem dixerunt, quod est ex radicibus anigailen . . .”

Bunchum, what is that? It comes from Yemen. Some say it derives from the roots of anigailen . . .

In explaining the medicinal properties and uses of bunchum and buncham, Avicenna uses these words in apparently the same way as Rhazes (the unroasted beans are yellow):

“As to the choice thereof, that of a lemon color, light, and of a good smell, is the best; the white and the heavy is naught. It is hot and dry in the first degree, or, according to others, cold in the first degree. It fortifies the members, it cleans the skin, and dries up the humidities that are under it, and gives an excellent smell to all the body.”

The name “Avicenna” is the Latinized form of the Arabic Ibn Sina, a shortened version of Abu Ali ai-Husain Ibn Abdollah Ibn Sina. Legend has it, that when only seventeen years old he cured his sultan of a long illness and was, in compensation, given access to the extensive royal library and a position at court.

Avicenna himself is credited with writing more than a hundred books. Some of his admirers claim, that modern medical practice is a continuation of his system, which framed medicine as a body of knowledge that should be clearly separated from religious dogma and be based entirely on observation and analysis.

Of course, the beverage about which these two men were writing was far from the coffee with which we are familiar with. Nonetheless, its spread from Ethiopia was rapid, as it was carried across the Red Sea by Arab traders and grown in Yemen. The Arabs, as the name for the seed of Arabica coffee suggests, were enjoying the pleasures of coffee. There is even a legend that says that the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) claimed that after drinking coffee he could ‘unhorse forty men and possess forty women’. Other Arabs disagree saying:

“black-faced coffee drives sleep and lust away.”

anonymous

Coffees names in the first historical writings

Chaube

In 1582, the German traveler, physician and botanist, Leonhard Rauwolf (1535-96), was the first European to mention coffee. He called it Chaube and described it as a hot drink, black as ink, which was enjoyed in company, especially in the morning, and also to treat various complaints, especially of the stomach. Probably coffee was meant.

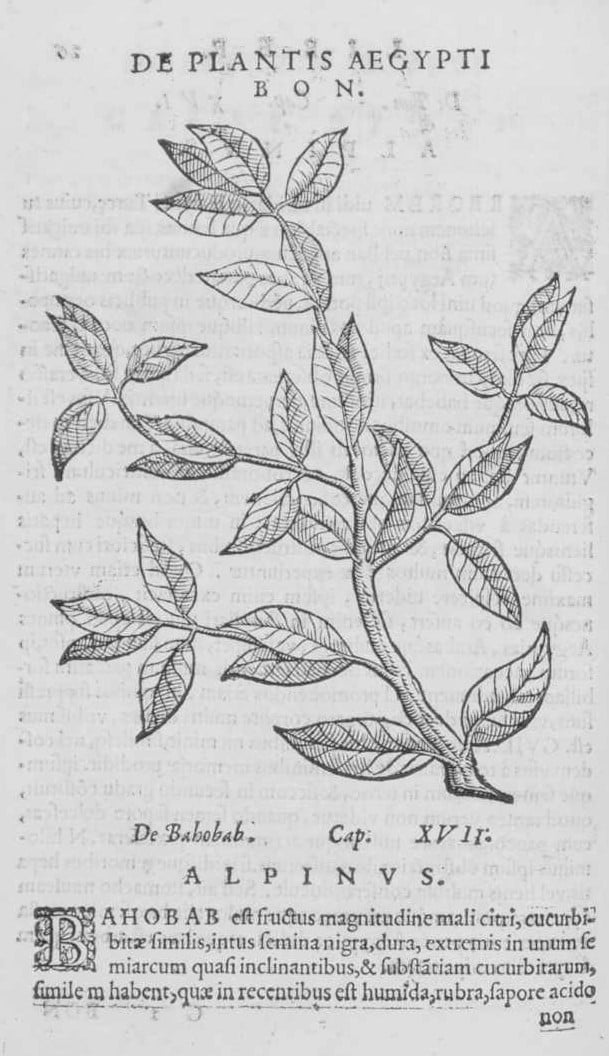

Bon

Prospero Alpino (1553-1617), a botanist and physician, is credited with the introduction to Europe of coffee and bananas. His book De Plantis Aegypti 1592, “Book of Egyptian Plants”, contains an illustration of the coffee plant.

In this volume he describes the plant called “Bon” and the custom of imbibing a dark energy-giving drink, obtained by boiling its berries: coffee.

Caova or Coffa

Francis Bacon,1561-1626, citing Alpinus, in his The Vertues of coffee set forth in the works of the Lord Bacon his Natural history, writes:

Alpinus in his Book of Egyptian Plants, giveth us the Description of this Tree, which, as he saith, he saw in the Garden of a certain Captain of the Janizaries, which was brought out of Arabia Foelix, and there plan∣ted as a rarity, never seen growing in those places before. The Tree (saith Alpinus) is somewhat like unto the Euonymus Pricketimber Tree, whose Leaves were thicker, harder, and greener, and always abiding green on the Tree:

The first is called Buna and is somewhat bigger then a Hazel Nut, and longer, round also, and pointed at the one end, fur rowed also on both sides, yet on one side more conspicuous then the other, that it might be parted into two, in each side whereof, lyeth a long small white Kernel, flat on that side they joyn together, covered with a yellowish skin, of an acide tast, and somewhat bitter withal, and contained in a thin shell of a darkish Ash colour;

with these Berries generally in Arabia and Egypt, and in other places of the Turks Dominions, they make a Decoction or Drink wich is instead of wine to them, and generally sold in all their Tap-houses, called by the name of Caova or Coffa;

this Drink hath many good Physical properties therein, for it strengthener a weak Stomach, helpeth digestion, and the tumours and obstructions of the Liver and Spleen, being drunk Fasting for some time together; the Egyptian and Arabian women use it familiarly while their Courses hold, to cause them to passe away with the more ease, as also to cause those to flow that are stayed, there bodies being prepared and purged afore hand.

Kohwah

Edward Pococke (1604-91) was an English Orientalist, Church of England priest and biblical scholar who sailed for Aleppo in 1630 as chaplain to an English merchant. He described coffee, calling it Kohwah, rather alarmingly, for example, in his 1659 translation, The Nature of the Drink Kauhi, or Coffee, and the Berry of which it is Made, Described by an Arabian physician:

Bun is a plant in Yaman [Yemen], … It may be that the scorce is hot, and the Bun it selfe either of equall temperature, or cold in the first degree. That which makes for its coldnesse is its stipticknesse. In summer it is by experience found to conduce to the drying of rheumes, and flegmatick coughes and distillations, and the opening of obstructions, and the provocation of urin. It is now known by the name of Kohwah.

When it is dried and thoroughly boyled, it allayes the ebullition of the blood, is good against the small poxe and measles, the bloudy pimples; yet causeth vertiginous headheach, and maketh lean much, occasioneth waking, and the Emrods, and asswageth lust, and sometimes breeds melancholly.

He that would drink it for livelinesse sake, and to discusse slothfulnesse, and the other properties that we have mentioned, let him use much sweat meates with it, and oyle of pistaccioes, and butter. Some drink it with milk, but it is an error, and such as may bring in danger of the leprosy.[sic]

Fabulous Ancient References to Coffee

Coffee does not appear in Ancient Greek or Roman writings although the Italian composer and author, Pietro della Valle (1586-1652) tells, that when Homer wrote about the nepenthe that Helen of Troja, took with her out of Egypt to assuage her sorrow, he was actually referring to coffee mixed with wine.

In the fourth book of the epic, in which Telemachus, Menelaus, and Helen are eating dinner, the company becomes suddenly depressed over the absence of Odysseus. Homer tells us:

Then Jove’s daughter Helen bethought her of another matter. She drugged the wine with an herb that banishes all care, sorrow, and ill humour. [Humourism was a medical system created by the Ancient Greeks and Romans that detailed the make-up and workings of the human body.]

Whoever drinks wine thus drugged cannot shed a single tear all the rest of the day, not even though his father and mother both of them drop down dead, or he sees a brother or a son hewn in pieces before his very eyes.

This drug, of such sovereign power and virtue, had been given Helen by Polydarnna wife of Thon, woman of Egypt, where there grow all sorts of herbs, some good to put into the mixing bowl and others poisonous. Moreover, every one in the whole country is a skilled physician. When Helen had put this drug in the bowl, . . . (she] told the servants to serve the wine round.

These wondrous effects sound more like those of opium mixed with some stimulant than of coffee mixed with wine. The word “nepenthes,” meaning “no pain” or “no care” in Greek, is used in the original text to modify the word “pharmakos,” meaning medicine or drug. For at least the last several hundred years, “nepenthe” has been a generic term in medical literature for a sedative or the plant that supplies it; as such, it hardly fits the pharmacological profile of either caffeine or coffee.

Nevertheless, the pioneering Enlightenment scholars Diderot and D’Alembert repeated Pietro della Valle’s idea in their Encyclopidie (much of which was drafted in daily visits to one of Paris’s earliest coffee houses). The fact that Homer tells us that the use of nepenthe was learned in Egypt, which can be construed to include parts of Ethiopia, together with the undoubted capacity of coffee to drive away gloom and its reputation for making it impossible to shed tears, may have helped to make this identification more appealing.

This claim is disputed, however, several scholars have suggested that the black broth of the Lacedaemonians (Spartans) was, in fact, coffee. Could that be possible?

The German theologian Georg Pasch (1661-1707) wrote in his 1700 Latin treatise, New Discoveries Made since the Time of the Ancients, that in the Bible, 1 Samuel, xxv, 18, the five measures of parched corn that were amongst the presents that King David was given by his wife Abigail in order to assuage his anger were actually coffee.

The Swiss-French Protestant minister and political writer Pierre Étienne Louis Dumont (1759-1829) claimed that it was coffee and not lentils that was the red pottage for which Esau sold his birthright. He also proposed that the parched grain Boaz ordered to be given to Ruth in the Old Testament was roasted coffee berries.

Dr. Simon Andre Tissot, a Swiss medical writer working in 1769, acknowledges the value of coffee as stimulant to the wit, but warns that we should neither underestimate its dangers nor exaggerate its value: for

“we have to ask ourselves whether Homer, Thucydides, Plato, Lucretius, Virgil, Ovid, and Horace, whose works will be a joy for all time, ever drank coffee.”

Coffee in medical writings, song, petitions and a handbill.

Coffee was ascribed miraculous properties by all kinds of people, from quacks to those who knew no better. Some lauded it, giving it healing qualities, while others damned it as little better than poison.

Oxford physician and founding member of the Royal Society, Dr Thomas Willis (1621-75), often prescribed a trip to the coffee house rather than the apothecary. It was claimed by many that it could cure drunkenness and even opponents of the beverage agreed with this. This particular power was celebrated in the song:

The Rebellious Antidote

Come, Frantick Fools, leave off your Drunken fits. Obsequious be and I’ll recall your Wits, From perfect Madness to a modest Strain For farthings four I’ll fetch you back again, Enable all your mene with tricks of State, Enter and sip and then attend your Fate; Come Drunk or Sober, for a gentle Fee, Come n’er so Mad, I’ll your Physician be.

Someone suggested that coffee could act as a good deodorant, while another said that had its properties been known in 1665, it would have been useful against the Great Plague of London in which 100,000 died in just 18 months. It was also recommended for use against the plague in the 1665 book, Advice Against the Plague, by the physician Gideon Harvey (1636/7-1702).

Others such as Dr Daniel Duncan (1649-1735) of the University of Montpellier occupied the middle ground. In his Wholesome Advice against the Abuse of Hot Liqueurs, he claimed that coffee was neither poison nor panacea and the celebrated, pioneering English physician, George Cheyne (1672-1743) agreed.

A Cup of Coffee: or, Coffee in its Colours, published in 1663, described coffee as a ‘loathsome potion’.

Houghton Library Harvard University

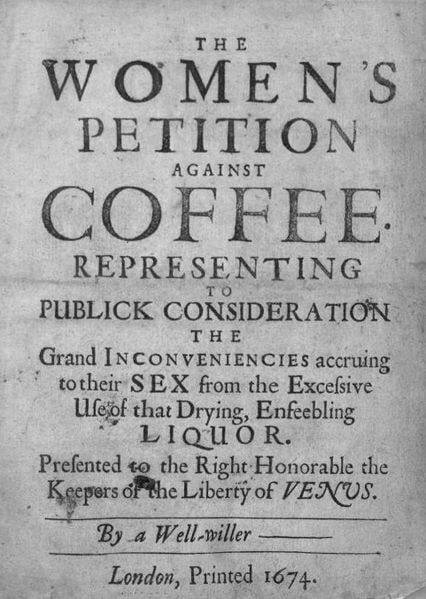

In 1674, The Women’s Petition against Coffee, representing to public consideration the grand inconveniences accruing to their sex from the excessive use of the drying and enfeebling Liquor was published, claiming that coffee made men impotent – as

“unfruitful as the deserts where that unhappy berry is said to be bought”.

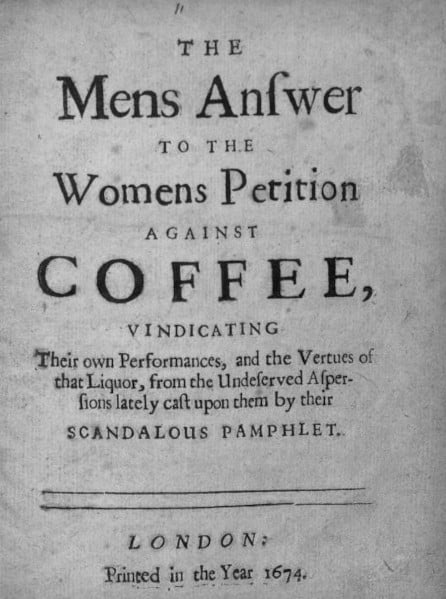

A response to it appeared in the same year, in the form of The Men’s Answer to the Women’s Petition Against Coffee, vindicating… their liquor, from the undeserved aspersion lately cast upon them, in their scandalous pamphlet.

Coffee’s effect on male virility was first suggested by the Danish doctor, Simon Paulli (1603-80) professor of botany, anatomy and surgery at Copenhagen University. Writing about tobacco and tea, Paulli was scathing about coffee which he called “cahvvae acqua”. He claimed that it

“surprisingly effeminates both the Minds and Bodies of the Persians”.

As for European men, he insisted that it made them like eunuchs,

“incapable of propagating their species…”

He argued that male consumers of coffee may still be able to ejaculate, but their semen will have lost its power to generate new life. His thinking was derived from the observations of Adam Olearius who, traveled to Muscovy and Persia between 1635 and 1639. In Persia in 1637, he observed that coffee was used as a contraceptive by Persian men due to the ‘Cooling quality’ they thought it possessed. They believed that it

“allays the Natural heat… and would avoid the charge of having many Children”.

Others argued that coffee had other qualities. In 1771, a French doctor claimed that coffee could cause nymphomania, as it stimulated women’s erotic imaginings. On the other hand, the German physician Samuel Hahnemann, the creator of homeopathy, blamed coffee for masturbation –

“the monster of nature, that hollow-eyed ghost, onanism, is generally concealed behind the coffee-table”.

Of course, there is absolutely no evidence that coffee plays a part in any of these indulgences and conditions and, in fact, more recent research has postulated that coffee may increase sperm mobility, thereby increasing male fertility.

In 1671, a Syrian living in Rome, published a treatise in Latin on the health-giving properties of coffee. Antonio Fausto Naironi (1635-1707) was unsure of its medical properties, and whether it was hot or cold in terms of the humours. Although his medical analysis of coffee was decidedly lacking in substance, his work remained influential in the science of coffee for the next 100 years, circulating widely around Europe. It was an indication of the curiosity that existed about the beverage and its effect on the human body and psyche.

Thomas Willis, mentioned earlier, was one of the Royal Society’s most eminent natural philosophers and was also a practitioner of new types of medicine. While remaining an adherent to the old methods, he also involved himself in more experimental science, analyzing skillfully the physiological effects of his treatments. He recommended coffee as a treatment for what he described as ‘sleepy Distempers’. And, while still recommending bloodletting and purging, the old methods, as a cure for persistent drowsiness, he also prescribed, “At eight of the Clock of the Morning, and at five in the Afternoon… a draught of coffee, or the Liquor prepared of that Berry”.

In Pharmaceutice Rationalis of 1674, Dr Willis supported both sides of the coin. On the one hand, he said that it was a risky drink that engendered listlessness and even paralysis. It could be dangerous, he claimed, for the heart and might create trembling in the limbs of a drinker. But, he believed that, if drunk carefully, it could provide benefits:

“being daily drunk it wonderfully clears and enlightens each part of the Soul and disperses all the clouds of every function”.

In his posthumously published book, The London Practice of Physick, of 1685, Willis recommends coffee for treating “Head-aches, Giddiness [and] the Lethargy”.

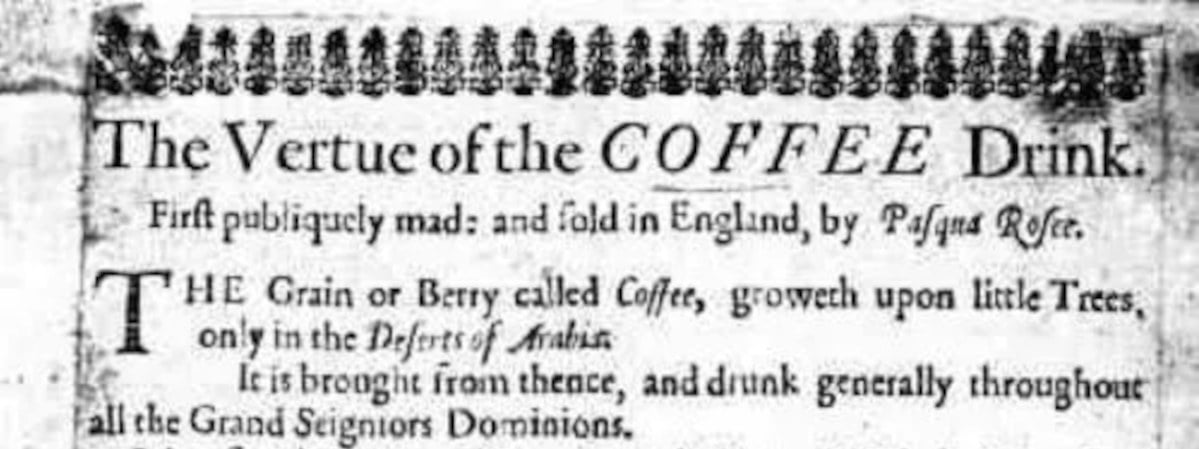

Advertisement for coffee—1652 Handbill used by Pasqua Rosée, who opened the first coffee house in London From the original in the British Museum.Public domain, edited.

Coffee house proprietors were keen to promote the therapeutic qualities of their beverage. Coffee, according to them, was a panacea:

Handbill of the Rainbow Coffee-House in Fleet Street London about coffee

The quality of this drink, is cold and dry; and though it be a drier, yet it neither heats, nor Inflames more than a hot Posset.

It so closeth the Orifice of the Stomach, and fortifies the heat within, that it is very good to help digestion, and therefore of great use to be taken about three or four of the Clock in the afternoon, as well as in the morning.

It is very good against sore Eyes, and the better, if you hold your head over it, and take in the Steam that way.

It suppresseth fumes exceedingly, and therefore good against the Headach, and will very much stop any Defluxion of Rhumes, that distil from the Head upon the Stomach, and so prevent, and help Consumptions, and the Cough of the Lungs.

It is excellent to prevent and cure the Dropsy, Gout, and the Scurvy.

It is known by experience to be better than any other drying Drink for people in years, or Children that have any running Humours upon them, as the King’s evil. &c.

It is very good to prevent Miscarryings in Child-bearing Women.

It is a most excellent remedy against the spleen, Hypochondriack Windes, or the like.

It will prevent drowsiness, and make one fit for business, if one have occasion to watch; and therefore you are not to Drink of it after Supper, unless you intend to be watchful, for it will hinder sleep for three or four hours.

It is to be observed that in Turkey, where this is generally drunk, that they are not troubled with the Stone, Gout, Dropsie, or Scurvy; and that their Skins are exceeding clear and white. It is neither Laxative nor Restringent.

Coffee diffusion

The history and cultural significance of coffee are fascinating and multifaceted. The Arab world has given birth to thinkers and inventions – among them the three-course meal, alcohol and coffee. The best coffee bean is still known as Arabica, but it’s come a long way from the Muslim mystics who treasured it centuries ago, to the bars, coffee houses and chains that line our streets today.

Scholars describe coffees migration from the genetically diverse center of Ethiopia to Yemen during the 6th century.

In the mountainous slopes (1200-1800 meters) and constricted valleys of Yemen and Saudi Arabia the cultivation of Arabica coffee has been continuous for the past 4-5 centuries. The Arabica coffee genome allows the plant to adapt remarkably through a vast range of environmental diversity of intertropical areas as it traveled to South-east Asia, India, East Africa and Latin America between the 17th to 19th centuries.

Arab trade

Legendary Sufi saints and real merchants where spreading the practice of coffee-drinking to the geographically diverse – but intellectually and linguistically linked Arabs –Ottoman coffeehouses, Iranian Safavid, and South Asian Mughal empires (India) – that reigned from the 16th to the 18th centuries.

Linked to the emergence of the public sphere and by extension modern democratic values, Western coffeehouses are effectively the descendants of the dynamic early modern Arabic coffeehouse culture.

Neha Vermani

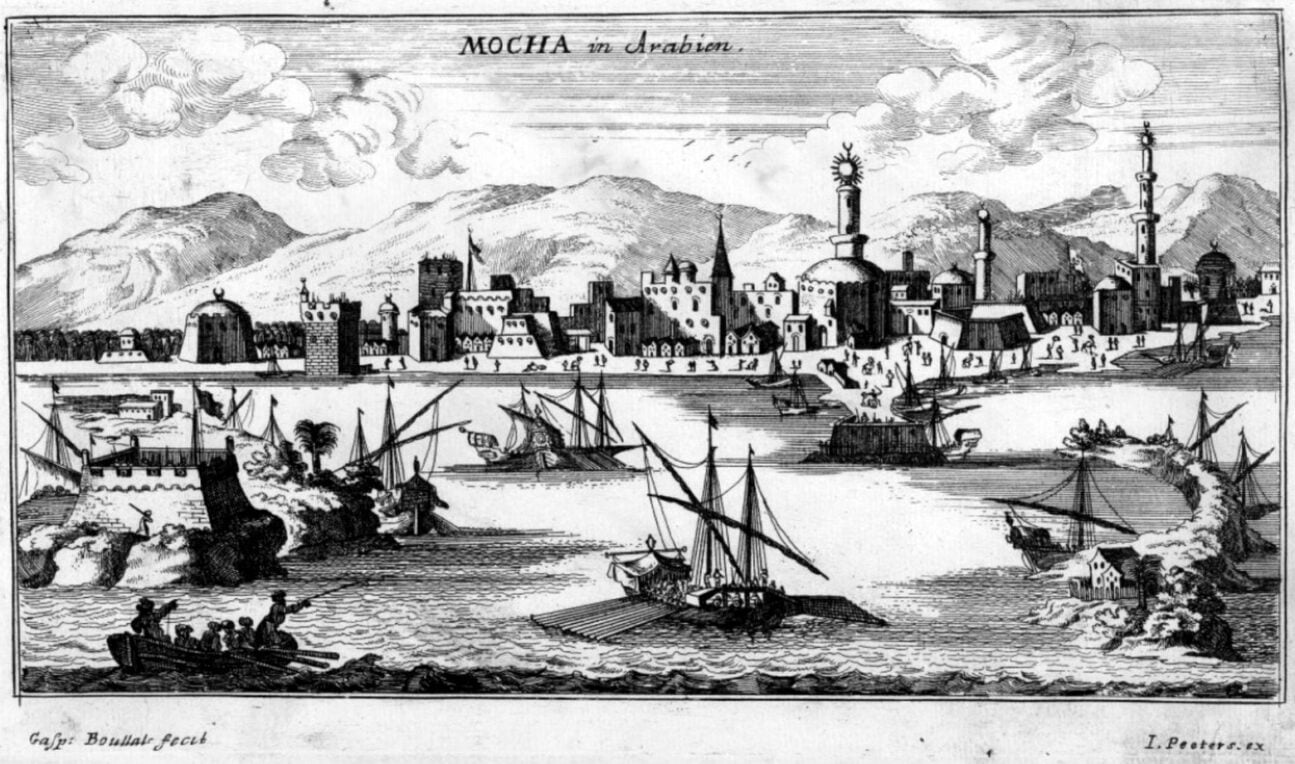

The 15th-century coffee trading network was based in the Red Sea region with the Yemeni port of Mocha as its focal point. Mocha received its supply from Abissinya, the Ethiopian highlands in northeast Africa, the natural habitat of what is now known as Arabica coffee.

From Yemen, the habit of drinking coffee traveled to Arabia and Egypt before becoming a dominant beverage in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Coffee spread to Europe by two routes – from the Ottoman Empire to Vienna, and by sea from the coffee port of Mocha to Venice.

Pieter van der Broeck

Pieter van der Broeck was a Dutch cloth merchant in the service of the Dutch East India Company, and one of the first Dutchmen to taste coffee. In 1616 he visited the port of Mocha, where he attempted, unsuccessfully to establish a permanent Dutch trading establishment. It was there that he drank “something hot and black, a coffee”

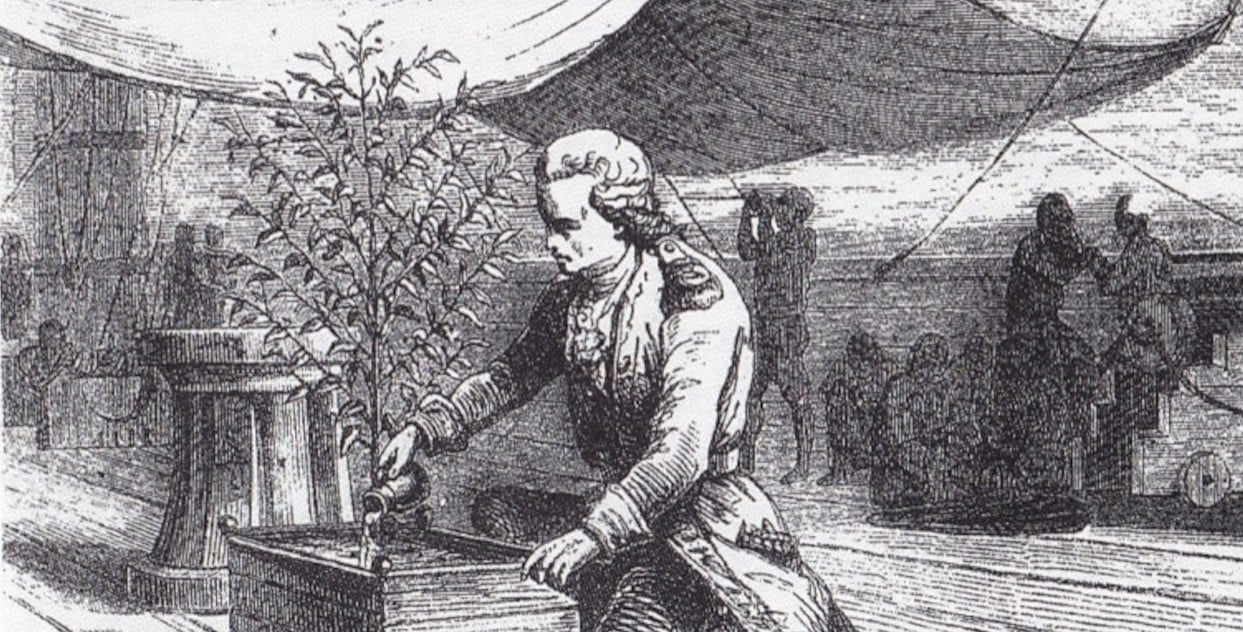

The seedlings that the Dutch merchant had stolen from Mocha adapted to the local climatic conditions in the greenhouses of the botanical garden of Amsterdam.

They produced numerous and lush bushes of Coffea Arabica.

In 1658 the Dutch used them to begin coffee cultivation in Ceylon, Java and South India.

Gabriel Mathieu de Clieu

Dutch supremacy on coffee production and trade, changed, when in 1714 the master of Amsterdam offered the French King Louis XIV, a special gift: two flowering coffee plants. They were kept in the royal greenhouses of Versailles and here, a former naval officer, Gabriel Mathieu de Clieu, stole one of the plants and transported it across the Atlantic. He thus began the cultivation of coffee in French Martinique, an island in the Antilles. In 1726 the gentleman-coffee thief made his first harvest. The following fifty years the plantations extended to the entire Caribbean area, from Haiti to Jamaica, up to Cuba and Puerto Rico.

English East India Company and the Dutch East India Company

Neha Vermani explains: by the 17th century the English East India Company and the Dutch East India Company had infiltrated the coffee trade, hitherto operated by the Arab, Cairenes, and Turkish merchants. By the 18th century, the English, the Dutch, and the French had succeeded in transporting and transplanting coffee seeds to their colonies in Indonesia, South India, Sri Lanka (Ceylon), and the Caribbean.

The Bean Belt: Geographical distribution of coffee producing countries

These plants grow best in an area know as the Bean Belt – the band around the earth in between the Tropics of Capricorn and Cancer. Today the top ten coffee producing countries are: Brazil, Colombia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Mexico, Ethiopia, India, Guatemala, Cote d’ Ivore and Uganda.

The mythical origins of coffee, are steeped in legend and topped with a creamy dollop of speculation.

From its discovery in Ethiopia to its global impact on culture, coffee has played an important role in shaping our world. Beyond being a delightful beverage, it holds a special place in cultures coffee rituals worldwide. It’s not just a drink; it’s a ritual that brings people together, reflects traditions, and offers a unique lens into the diverse tapestry of global societies.

Amidst the hustle and bustle of daily life, setting aside a moment to savor a cup of coffee can be an act of self-care and self-reward. The experience of sipping a well-prepared coffee can be truly pleasurable, engaging all our senses, from the delightful aroma to the comforting taste.

A remarkable difference between coffee and all the other beverages is the extraordinary variety of brewing techniques, so Petracco, 2001, that have been developed and used traditionally in different countries:

decoction methods (boiled coffee, Turkish coffee, percolator coffee and vacuum coffee),

infusion methods (drip filter coffee, Indian filter Kapi and Napoletana), and

Italian pressure methods (Moka and espresso)

Millions of people grow, prepare, and consume coffee every day. Coffee culture is an intricate tapestry of rituals, traditions, and historical significance that has woven its way into the fabric of societies around the world.

Coffee is much more than a stimulating beverage; it’s a source of well-being, inspiration, and social connection, it continues to captivate people’s hearts and taste buds, as a beverage and as a cultural touchstone.

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

Thank you Klaus Langrock for proofreading.

The history of coffee is an extraordinary study. If you would like to learn more about it, we heartily recommend the book, All About Coffee, by William Ukers. Written in 1928, it is as good a book on coffee as has been written and will delight you with detail.

Also the new book Short History of Coffee, by Kerr Gordon is delightful.

- Nehlig A, Daval JL, Debry G.. Caffeine and the central nervous system: mechanisms of action, biochemical, metabolic and psychostimulant effects. 1992.

- Pendergrast Mark. Uncommon Grounds. The History of Coffee and How It Transformed Our World. 2019.

- https://www.folger.edu/blogs/shakespeare-and-beyond/islamic-history-of-coffee/

- Caffeine: The Motivation Molecule https://blogs.loc.gov/inside_adams/2022/10/caffeine/

- 2D structure of caffeine, by NEUROtiker (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.