The mythical origins of coffee, are steeped in legend and topped with a creamy dollop of speculation.

In this Article

According to William Harrison Ukers, it’s commonly accepted that coffee originated from Abyssinia (presently Ethiopia), and Arabia (Yemen where it was possibly first farmed).

The Kaffa Kingdom may have baptized the plant with its name. Another etymology suggests that coffee comes from the Arabic meaning “dark color”, originally used for wine, possibly made of the whole coffee cherries.

With every cup of coffee you drink, you partake of one of the great mysteries of cultural history. Despite the fact that the coffee plant, grows wild in highlands throughout Africa, from Madagascar to Sierra Leone, from the Congo to the mountains of Ethiopia, it may also be indigenous to Arabia.

Both the Arabica and Robusta varieties have their origins in Ethiopia. Around 5,000 varieties of Arabica grow there, more than in any other country on earth.

To drink a coffee is a deeply cultural process that invites to delve into history, heritage, folklore and legends about Coffee.

Legendary Coffee heritage

Although European and Arab historians repeat legendary African accounts or cite lost written references from as early as the sixth century, surviving documents can establish coffee drinking or knowledge of the coffee tree no earlier than the middle of the fifteenth century in the Sufi monasteries of Yemen and southern Arabia.

Sufis and the ritual use of Coffee

The common and perhaps most accurate explanation accepted by historians today is that coffee originated from the Sufi orders of Yemen where caffeine was essential to religious practice.

As opposed to practicing the structured prayer indicative of traditional Muslims, the Sufis consumed stimulants and danced fitfully to demonstrate their devotion to Allah. Such a practice required the consumption of something that could sustain them for many days.

The Sufis lived on the fringes of Ottoman society and coffee’s connection to their orders stirred speculation. Kâtib Celebi, the famous Ottoman historian, described coffee’s first users as

“Certain sheiks, who lived with their dervishes in the mountains of Yemen, used to crush and eat their berries, which they called qalb wabūn, […] a cold dry food, suited to the ascetic life and sedative of lust.”

Legendary animals of Ethiopia discover and spread coffee

The myth of Kaldi the Ethiopian goatherd and his dancing goats, is the coffee most frequently encountered coffee origin story in Western literature.

This legend enhances the credible tradition that the Sufi encounter with coffee occurred in Ethiopia, which lies just across the narrow passage of the Red Sea from Arabia’s western coast.

The legend of Kaldi and his dancing goats

Antoine Faustus Nairon, was a Maronite who became a Roman professor of Oriental languages and author of one of the first printed treatises devoted to coffee, De Saluberrimd Cahue seu Cafi mmcupata Discurscus (1671).

Nairon relates that Kaldi, noticing the energizing effects when his goats nibbled on the bright red berries of a glossy green bush with fragrant blossoms. The goats were prancing, frolicking, and dancing.

Kaldi brought the berries to an sacred man in a nearby monastery. But the holy man found nothing special about the red cherries and threw them into the fire. An enticing aroma billowed and the roasted beans were quickly taken from the embers, ground up, and dissolved in hot water, yielding the world’s first cup of coffee.

Kaldi is not a mytho-poetic emblem of some actual person, this tale does not appear in any earlier Arab sources and must therefore be supposed to have originated in Nairon’s caffeine-charged literary imagination and spread because of its appeal to the earliest European coffee sippers.

A French version of the legend: Kaldi and his dancing goats

A young goatherd named Kaldi noticed one day that his goats, whose deportment up to that time had been irreproachable, were abandoning themselves to the most extravagant prancing. The venerable buck, ordinarily so dignified and solemn, bounded about like a young kid, prancing, frolicking, and dancing.

The goat herder attributed this foolish gaiety to certain fruits of which the goats had been eating with delight.

One day Kaldi had a heavy heart; and in the hope of cheering himself up a little, he thought he would pick and eat of the fruit. The experiment succeeded marvelously. When the goats danced, he gaily entered into their fun with admirable spirit.

One day, a wandering monk stopped in surprise watching the dance. The goats were executing lively pirouettes like a ladies’ chain, while the buck solemnly balancé-ed, and the herder went through the figures of an eccentric pastoral dance.

The astonished monk inquired the cause of this and Kaldi told him of his precious discovery.

Now, this poor monk had a great sorrow; he always went to sleep in the middle of his prayers; and he reasoned that Mohammed (p.b.u.h.) without doubt was revealing this marvelous fruit to him to overcome his sleepiness.

The good monk thought of drying and boiling the fruit of the herder. This ingenious concoction gave us coffee.

The Abbot of the wakeful monastery

Another version of this Oriental legend gives it as follows:

An Arabian herdsman in upper Egypt, or Abyssinia, complained to the abbot of a neighboring monastery that the goats confided to his care became unusually frolicsome after eating the berries of certain shrubs found near their feeding grounds. The abbot, having observed the fact, determined to try the virtues of the berries on himself. He, too, responded with a new exhilaration. Accordingly, he directed that some be boiled, and the decoction drunk by his monks, who thereafter found no difficulty in keeping awake during the religious services of the night.

The Abbé Massieu in his poem, Carmen Caffaeum, thus celebrates the event:

The monks each in turn, as the evening draws near,

Drink ’round the great cauldron—a circle of cheer!

And the dawn in amaze, revisiting that shore,

On idle beds of ease surprised them nevermore!

According to this legend, the news of the “wakeful monastery” spread rapidly, and the magical berry soon “came to be in request throughout the whole kingdom; and in progress of time other nations and provinces of the East fell into the use of it.”

Legend: A civet cat brings coffee from central Africa to Ethiopia

Another origin story, attributed to Arabian tradition by the missionary Reverend Doctor J. Lewis Krapf, in his Travels, Researches and Missionary Labors Dzn-ing Eighteen Years Residence in Eastern Africa (1856), also ascribes an essential part in the early progress of coffee to African animals. The tale enigmatically relates that the civet cat carried the seeds of the wild coffee plant from central Africa to the remote Ethiopian mountains. There the plant was first cultivated, in Arusi and llta-Gallas, home of the Galla warriors.

Finally, an Arab merchant brought the plant to Arabia, where it flourished and became known to the world. The so-called cat to which Krapf refers is actually a relative of the mongoose.

By adducing its role in propagating coffee, Krapf’s tale was undoubtedly referencing the civet cat’s predilection for climbing coffee trees and pilfering and eating the best coffee cherries, as a result of which the undigested seeds are spread by means of its droppings.

Kopi Luwak, the famous (or infamous) Indonesian coffee is a product of the droppings of the Asian palm civet and the world’s most expensive coffee today.

The Galla Tribe and coffee

Both stories, of prancing goats and wandering cats, reflect the reasonable supposition that Ethiopians, the ancestors of today’s Galla tribe, the legendary raiders of the remote Ethiopian massif, were the first to have recognized the energizing effect of the coffee plant.

According to this theory, which takes its support from traditional tales and current practice, the Galla, in a remote, chronicled past, gathered the ripe cherries from wild trees, ground them with stone mortars, and mixed the mashed seeds and pulp with animal fat, forming small balls that they carried for sustenance on war parties.

The flesh of the fruit is rich in caffeine, sugar, and fat and is about 15 percent protein. This preparation of the Galla warriors was a compact solution to the problems of hunger and exhaustion.

James Bruce of Kinnarid, F.R.S. (1730-94), Scottish wine merchant, consul to Algiers and the first modem scientific explorer of Africa, left Cairo in 1768 via the Red Sea and traveled to Ethiopia. There he observed and recorded in his book, Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile (1790), the persistence of what are thought to have been these ancient Gall:

En uses of coffee:

The Galla: is a wandering nation of Africa, who, in their incursions into Abyssinia, are obliged to traverse immense deserts, and being desirous of falling on the towns and villages of that country without warning, carry nothing to eat with them but the berries of the Coffee tree roasted and pulverized, witch they mix with grease to a certain consistency that will permit of its being rolled into masses about the size of billiard balls and then put in leathern bags until required for use.

One of these balls, they claim will support them for a whole day, when on a marauding incursion or in active war, better than a loaf of bread or a meal of meat, because it cheers their spirits as well as feeds them.

Other tribes of northeastern Africa are said to have cooked the berries as a porridge or drunk a wine fermented from the fruit and skin and mixed with cold water, much like sun tea is made today.

Despite credible inferences about its African past, no direct evidence has ever been found revealing exactly where in Africa coffee grew or who among the natives might have used it as a stimulant or even known about it there earlier than the seventeenth century.

Ethiopian coffee preparation with the traditional clay pot and coffee ceremonies are a cornerstone of hospitality and a social occasion to connect with friends and family.

Coffee is now loved worldwide. In many cultures, like in Turkey and Italy, inviting someone for coffee is seen as a gesture of hospitality and friendship. This age-old tradition has the power to bring people from different backgrounds and lifestyles together, breaking cultural barriers and creating a sense of belonging to a global community.

The legend of Sheik Omar

There are several traditions that have persisted through the centuries, claiming for “the faithful” the honor and glory of the first use of coffee as a beverage. One of these relates how, about 1258 AD, Sheik Omar, a disciple of Sheik Abou’l hasan Schadheli, patron saint and legendary founder of Mocha (al-Mukha), Yemen, by chance discovered the coffee drink at Ousab in Arabia, whither he had been exiled for a certain moral remissness.

Facing starvation, he and his followers were forced to feed upon the berries growing around them, that also the Coffee Bird would eat. And then, in the words of the faithful Arab chronicle in the Bibliothéque Nationale at Paris,

“having nothing to eat except coffee, they took of it and boiled it in a saucepan and drank of the decoction.”

Former patients in Mocha who sought out the good doctor-priest in his Ousab retreat, for physic with which to cure their ills, were given some of this decoction, with beneficial effect. As a result of the stories of its magical properties, carried back to the city, Sheik Omar was invited to return in triumph to Mocha where the governor caused to be built a monastery for him and his companions.

The legend of dervish Hadji Omar

Another version of this Oriental folklore gives it as follows:

The dervish Hadji Omar was driven by his enemies out of Mocha into the desert, where they expected he would die of starvation. This undoubtedly would have occurred if he had not plucked up courage to taste some strange berries which he found growing on a shrub. While they seemed to be edible, they were very bitter; and he tried to improve the taste by roasting them. He found, however, that they had become very hard, so he attempted to soften them with water. The berries seemed to remain as hard as before, but the liquid turned brown, and Omar drank it on the chance that it contained some of the nourishment from the berries. He was amazed at how it refreshed him, enlivened his sluggishness, and raised his drooping spirits. Later, when he returned to Mocha, his salvation was considered a miracle.

The beverage to which it was due sprang into high favor, and Omar himself was made a saint.

Variant: The legend of Sheik Omar and Mollah Schadheli

A popular and much-quoted version of Omar’s discovery of coffee, also based upon the Abd-al-Kâdir manuscript, is the following:

In the year of the Hegira 622 CE (the Prophet Muhammad’s pbuh.migration from Mecca to Yathrib (Medina)), the mullah Schadheli went on a pilgrimage to Mecca. Arriving at the mountain of the Emeralds (Ousab), he turned to his disciple Omar and said: “I shall die in this place. When my soul has gone forth, a veiled person will appear to you. Do not fail to execute the command which he will give you.”

The venerable Schadheli being dead, Omar saw in the middle of the night a gigantic specter covered by a white veil.

“Who are you?” he asked.

The phantom drew back his veil, and Omar saw with surprise Schadheli himself, grown ten cubits since his death. The mollah dug in the ground, and water miraculously appeared. The spirit of his teacher bade Omar fill a bowl with the water and to proceed on his way and not to stop till he reached the spot where the water would stop moving.

“It is there,” he added, “that a great destiny awaits you.”

Omar started his journey. Arriving at Mocha in Yemen, he noticed that the water was immovable. It was here that he must stop.

The beautiful village of Mocha was then ravaged by the plague. Omar began to pray for the sick and, as the saintly man was close to Mahomet, many found themselves cured by his prayers.

The plague meanwhile progressing, the daughter of the King of Mocha fell ill and her father had her carried to the home of the dervish who cured her. But as this young princess was of rare beauty, after having cured her, the good dervish tried to carry her off. The king did not fancy this new kind of reward. Omar was driven from the city and exiled on the mountain of Ousab, with herbs for food and a cave for a home.

“Oh, Schadheli, my dear master,” cried the unfortunate dervish one day; “if the things which happened to me at Mocha were destined, was it worth the trouble to give me a bowl to come here?”

To these just complaints, there was heard immediately a song of incomparable harmony, and a bird of marvelous plumage came to rest in a tree. Omar sprang forward quickly toward the little bird which sang so well, but then he saw on the branches of the tree only flowers and fruit. Omar laid hands on the fruit, and found it delicious. Then he filled his great pockets with it and went back to his cave. As he was preparing to boil a few herbs for his dinner, the idea came to him of substituting for this sad soup, some of his harvested fruit. From it he obtained a savory and perfumed drink; it was coffee.

Solomon and the angel Gabriel

The Turk Abu al-Tayyib al-Ghazzi suggested a biblical origin of coffee,

“in which Solomon appears as the first to make use of coffee.”

After brewing the cherries Solomon presented the caffeinated drink to angel Gabriel who used the brew to cure the sick.

William Ukers cites early writers who speculated that coffee did appear in the Bible. For example, they suggest that the pottage for which Esau sold his birthright (Genesis 25) was coffee, the grain that Ruth received from Boaz (Ruth 2) was coffee, and coffee was among David’s presents from Abigail (1 Samuel 25). These passages in today’s Bible translations do not talk about coffee and also Ukers did not believe in an early “biblical” use.

The Prophet (pbuh) and the angel Gabriel

Another tradition tells how coffee was revealed to the Prophet Mohammad (peace be upon him) himself by the Angel Gabriel. Coffee’s partisans found satisfaction in a passage in the Koran which, they said, foretold its adoption by the followers of the Prophet (pbuh):

“They shall be given to drink an excellent wine (coffee), sealed; its seal is that of the musk.”

Prophet Mohammad (peace be upon him) receiving his first revelation from the angel Gabriel. Miniature illustration on vellum from the book Jami’ al-Tawarikh (literally “Compendium of Chronicles” but often referred to as The Universal History or History of the World), by Rashid al-Din, published in Tabriz, Persia, 1307 CE Now in the collection of the Edinburgh University Library, Scotland.

Representations of the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) are controversial, and generally forbidden in Sunni Islam (especially Hanafiyya, Wahabi, Salafiyya). Shia Islam and some other branches of Sunni Islam (Hanbali, Maliki, Shafi’i) are generally more tolerant of such representational images, but even so the Prophet’s features are generally veiled or concealed by flames as a mark of deep respect.

A poor Arab discovers coffee

A little known version of coffee’s origin written on Harper’s Weekly. New York, 1911, tells the following legend about coffee:

Toward the middle of the fifteenth century, a poor Arab was traveling in Abyssinia. Finding himself weak and weary, he stopped near a grove. For fuel wherewith to cook his rice, he cut down a tree that happened to be covered with dried berries. His meal being cooked and eaten, the traveler discovered that these half-burnt berries were fragrant. He collected a number of them and, on crushing them with a stone, found that the aroma was increased to a great extent. While wondering at this, he accidentally let the substance fall into an earthen vessel that contained his scanty supply of water.

A miracle! The almost putrid water was purified. He brought it to his lips; it was fresh and agreeable; and after a short rest the traveler so far recovered his strength and energy as to be able to resume his journey. The lucky Arab gathered as many berries as he could, and having arrived at Aden, informed the mufti of his discovery. That worthy was an inveterate opium-smoker, who had been suffering for years from the influence of the poisonous drug. He tried an infusion of the roasted berries, and was so delighted at the recovery of his former vigor that in gratitude to the tree he called it cahuha which in Arabic signifies “force”.

Scialdi and Ayduis, discover Coffee

The Italian Journal of the Savants for the year 1760 says that two monks, Scialdi and Ayduis, were the first to discover the properties of coffee, and for this reason became the object of special prayers.

Baba Budan brings Coffee to India

Baba Budan, a Sufi named Hazrat Shah Jamer Allah Mazarabi, is said to have smuggled seven live coffee beans from Mocha to India when he returned from the Hadj, pilgrimage, and planted them in Mysore (today’s Karnataka) on the slopes of the Chandragiri Hills.

Folklore has it that Baba Budan broke the Arab monopoly over the coffee trade. A dangerous undertake. The penalty for anyone caught smuggling raw beans was death. Only roasted coffee beans were traded, and these through the port of Mocha in order to retain control. This was done to ensure that the only coffee trees growing were grown in Yemen.

While traveling home through the port of Mocha, Baba Budan enjoyed coffee and learned as much as possible about coffee and the coffee plant and decided to bring some seeds home with him. He procured seven seeds – seven being a sacred number in his religion – which he hid in his beard, on the belly and in his cane. After arriving home safely, he planted the seeds and grew the first Arabica beans on Indian soil.

An early date of 1385 has been given for the occurrence, but Baba Budan probably went to India no earlier than 1600 and more likely about 1690.

The Baba Budan Mountain is famous for the shrine of Sufi Saint, Baba Budan, who is worshiped by both Hindus and the Muslims. We visit the mountain range of Baba Budan and the shrine on our coffee road trip with our friend Avnish, enjoying every sip of coffee knowledge we could get.

HISTORY: The true story of coffee

The first mention of coffee in print appears in the writings of the Persian polymath and physician, Abū Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariyya al-Razi (854-925 AD), known also as Rhazes. In his writings, he mentions a drink called bunchum, describing it as

‘hot and dry and very good for the stomach’.

Around 1000 AD, another Arab physician, Abu Ali Sina (980-1037), known in the West as Avicenna, also wrote about bunchum, the name of coffee:

As to the choice thereof, that of a lemon color, light, and of a good smell, is the best; the white and the heavy is naught. It is hot and dry in the first degree, and, according to others, cold in the first degree. It fortifies the members, it cleans the skin, and dries up.

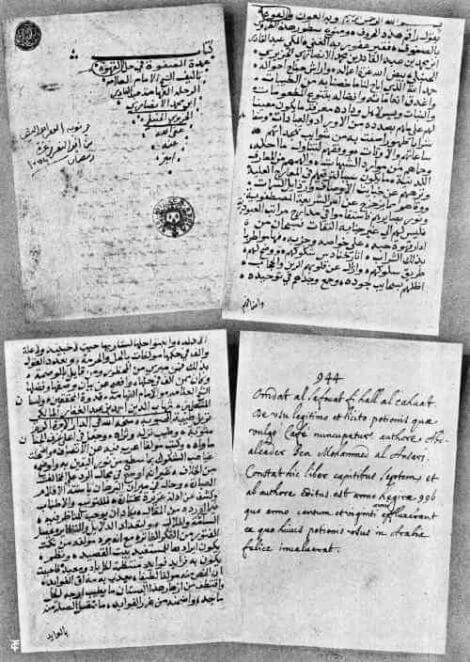

The Arabian manuscript commending to the use of coffee, preserved in the Bibliothéque Nationale, Paris, and catalogued as “Arabe, 4590.” The 1587 Argument in favor of the legitimate use of coffee, records a meeting between a Yemeni jurist and Shaykh Jamal al-Din Abu Abd Allah Muhammad ibn Sa’id al-Dhabbani, an imam, mufti, and Sufi from Aden.

He died about 1470, the account establishes coffee as a beverage by the mid-15th Century.

The Abd-al-Kâdir work immortalized coffee. It is in seven chapters.

The first treats of the etymology and significance of the word cahouah – kahwa – قهوة and properties of the bean, where the drink was first used, and describes its virtues. It also states:

How coffee traveled from Arabia Felix (Yemen) north to Medina and Mecca, and later onto the big cities of Damascus, Cairo, Ottoman coffeehouses and Baghdad.

The other chapters have to do with the dispute in Mecca in 1511, answer the religious objectors to coffee, and concludes with a collection of Arabic verses composed during the Mecca prohibition by the best poets of the time.

Coffee had then been in common use since about 1450 AD in Arabia. It was not drunk in the time of the Prophet pbuh., who died in 632 AD

Strong liquors which affect the brain were forbidden, and hence it was argued that coffee, as a stimulant was unlawful. Till today, the Wahabis, do not permit the use of coffee.

In his writings Sheik Abd-al-Kadir states,

“No one can understand the truth until he drinks of coffee’s frothy goodness.”

The following are two of the earliest Arabic poems in praise of coffee. They are about the period of the first coffee persecution in Mecca (1511):

In Praise of Coffee

Translation from the Arabic:

O Coffee! Thou dost dispel all cares, thou art the object of desire to the scholar.

This is the beverage of the friends of God; it gives health to those in its service who strive after wisdom.

Prepared from the simple shell of the berry, it has the odor of musk and the color of ink.

The intelligent man who empties these cups of foaming coffee, he alone knows truth.

May God deprive of this drink the foolish man who condemns it with incurable obstinacy.

Coffee is our gold. Wherever it is served, one enjoys the society of the noblest and most generous men.

O drink! As harmless as pure milk, which differs from it only in its blackness.

Here is another, rhymed version of the same poem:

O coffee!

Doved and fragrant drink, thou drivest care away,

The object thou of that man’s wish who studies night and day.

Thou soothest him, thou giv’st him health, and God doth favor those

Who walk straight on in wisdom’s way, nor seek their own repose.

Fragrant as musk thy berry is, yet black as ink in sooth!

And he who sips thy fragrant cup can only know the truth.

Insensate they who, tasting not, yet vilify its use;

For when they thirst and seek its help, God will the gift refuse.

Oh, coffee is our wealth! for see, where’er on earth it grows,

Men live whose aims are noble, true virtues who disclose

The history and cultural significance of coffee are fascinating and multifaceted. From its discovery in Ethiopia to its global impact on culture, coffee has played an important role in shaping our world.

Its popularity and importance are evident in the millions of people who grow, prepare, and consume it every day. From Ottoman coffeehouses serving Turk Khavesi to Italian coffee culture with espresso and cappuccino and South Indian filter Kapi, as we look to the future, it’s clear that coffee will continue to be an important part of our lives, both as a beverage and as a cultural touchstone.

Thank you,

Ethiopian people, legendary Sufi Saints, dancing goats, curious Kaldi and gourmand civet cats.

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

The history of coffee is an extraordinary study. If you would like to learn more about it, we heartily recommend the book, All About Coffee, by William Ukers. Written in 1928, it is as good a book on coffee as has been written and will delight you with detail.

Also the new book Short History of Coffee, by Kerr Gordon is delightful.

Thank you Klaus Langrock for proofreading.

- Coffee in Turkey.

- Kiple Kenneth F., Coneè Ornelas Kriemhild. The Cambridge World History of Food. Volume 1. 2000.

- Stefan’s Florilegium. Qawha-Coffee.

- The espresso and coffee guide.

- The Turkish Coffee Culture and Research Association.

- Turkish Coffee Reading: Fortunes, Methods, and Mysteries