Discover the Coffee Regions of India and South Indian coffee culture: How traditional filter kaapi is prepared and how charming Indian coffee houses are part of Indian heritage.

In this Article

The Ghats, the home of Indian coffee

Through dense tropical forests interspersed with lush grassy slopes and plantations, we arrived in Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh, where we have been drinking delicious filter kaapi and eating the biggest Laddus.

Riding in Tamil Nadu, we saw wild elephants and Gaurs in blooming coffee- and tea plantations – colorful birds everywhere. Kerala grows coffee in verdant Idduki, home to numerous crops, spices and medicinal plants. The smell of roasted coffee lingers on the roads of Orissa, Vanja brewed us delicious Kēāphi, କଫି, in Bhubaneshwar. The magnificent aroma of hot, freshly brewed filter kaapi (coffee) will hover over most South Indian kitchens.

The scent of coffee is the aroma of home-brewed memories and emotions, a fragrance both evocative and personal, that can transport you to a sprawling coffee house or a cozy breakfast with loved ones.

We visited Karnataka with our friend, Avnish, during Arabica harvesting season in order to gain a deeper understanding of the local coffee culture – enjoying every sip of coffee knowledge we could get.

Countless coffee estates are situated amidst the Western Ghats, a heavily forested area where the coffee trees thrive. Karnataka is the largest producer of coffee in India, with over 70% of the country’s production. A perpetual fragrance of coffee lingering in the air. There are more than 4500 such plantations in India, and they’re mostly located at a high altitude of around 1,300 metres above sea level.

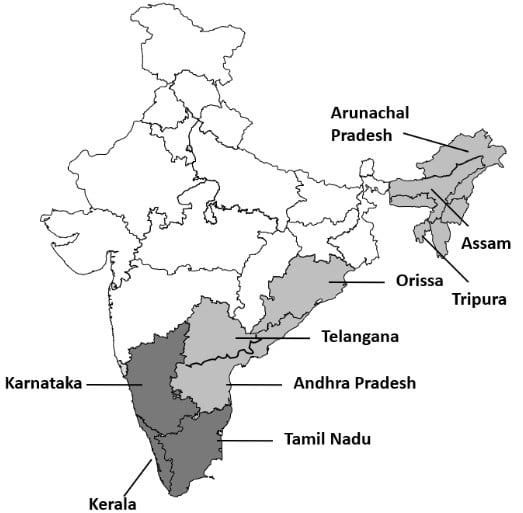

Coffee Regions of India

The journey of coffee’s aroma is a sensory adventure, that spans the Western Ghats – Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Karnataka. Karnataka’s coffee plantations, take up more than 60% of the total area in India that’s used for cultivating coffee.

The Eastern Ghats – Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, and Orissa.

As well as Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Tripura, Nagaland and Arunachal Pradesh in the North East, the new coffee growing regions of India .

From Bean to Brew: The aromatic journey of the coffee cherries

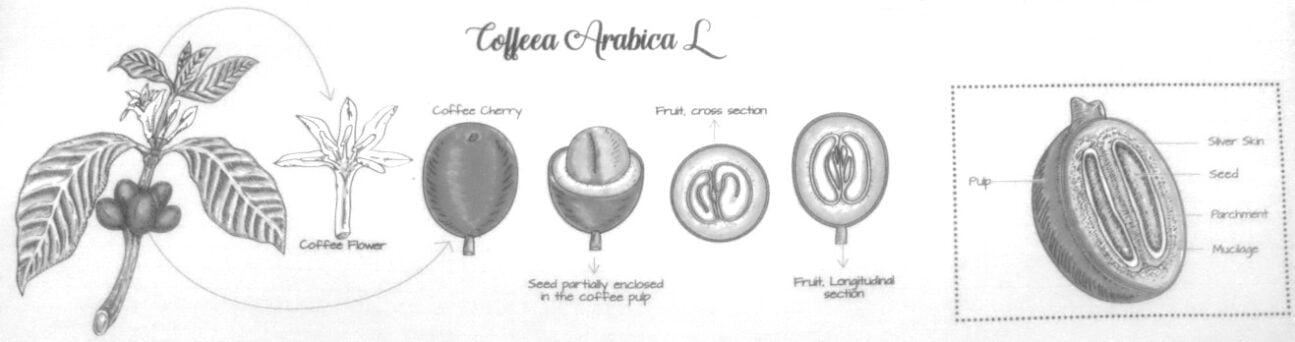

Coffee beans are the pits of the red fruit of the coffee cherry – the seeds.

The journey of the coffee bean – to cup starts with the blooming of the sparkling coffee blossoms; their scent reminds us jasmine. These become coffee berries that take about eight to ten months to mature and turn crimson.

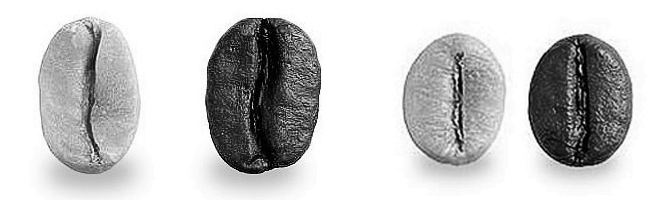

After the manual harvest, where only the ripe fruits are picked, the coffee beans go through a laborious process to become ready for roasting. The fruity cherries are hand sorted, dried, washed and peeled. The transition from raw to fragrant puts the seeds through fiery temperatures of between 180 to 230 C. It’s in this process that the character of coffee emerges. Quality checks are undertaken at each stage of production to ensure the best quality. They are finally ready for grinding and brewing.

Indian coffee is produced in different geographies, under varying degrees of rainfall. These variations bring subtle but delicious variations to the flavor of Indian coffee. The intricate relationship between nature, craftsmanship, and the human senses in India gives birth to both Arabica (around 1/3 of production) and Robusta (around 2/3 of production) varieties of coffee.

Arabica coffee (Coffea Arabica L) is a small tree in its original habitat but grows like a shrub with bushy growth when trained. Arabica has a delicate flavor and balanced aroma, coupled with a sharp and sweet taste. They have about half the amount of caffeine compared to Robustas. Arabica is susceptible to diseases like leaf rust and pests like the white stem borer. Arabicas are harvested from November to January and are typically grown on higher altitudes ranging from 600 to 2000 meters in cool, moisture-rich, and subtropical weather conditions with rainfall ranging from 1600 to 2500mm.

Coffee Arabica is a delicate creature that requires fertile soil, and coffee farmers meticulously nurture the plant preventing diseases, and managing shade and sunlight exposure.

Robusta (Coffea Canephora) is harvested between December and February at 500 to 1000 meters in hot and humid climates. Robusta is less fussy about its environment. It puts up better resistance to pests compared to Arabica. Today, Robusta accounts for 30% to 40% of the world’s coffee production.

Making aromas blossom from the coffee beans

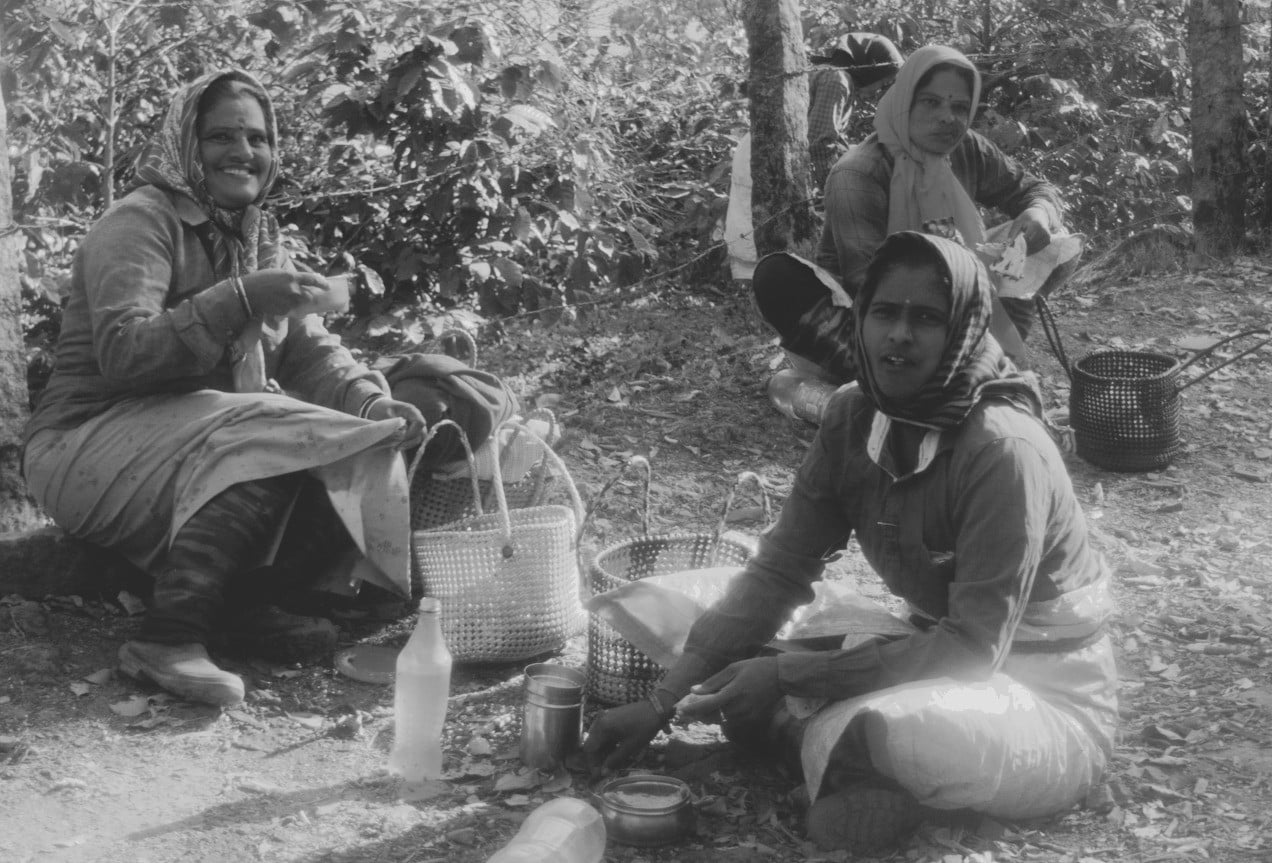

Each cup we savor is a testament to the artistry of nature and the expertise of those who cultivate and harvest the beans, quality coffee has its origins in the heart of the coffee plantations of India.

Home to a community of farmers, families, and workers who help bring delicious coffee to our table.

Coffee-growing is a science, taking into account soil quality, moisture content, monitoring sugar levels, and using the latest technology.

The ecologically sensitive regions of the Western and Eastern Ghats are a biodiversity hot spot of the world. Coffee contributes significantly to sustaining the unique diversity of the region and is also responsible for the socioeconomic development of the remote, hilly areas. The Ghats, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, make the perfect environment for coffee, with the altitude, rainfall, and temperature all contributing to the plant’s growth and flavor.

We stood in awe as the mist overpowered the mountains.

Flavorful Tapestry of Heritage – Indian Coffee Culture

Without a filter, coffee in the morning is like without the sun in the sky.

coffee.in

Each step of the brewing process releases a symphony of aromas, captivating our senses and building anticipation for that first invigorating sip. Brewing coffee produces even more aroma, as the hot water extracts different chemicals. According to science, coffee is one of the most appetizing smells for humans. The coffee chemistry that gives coffee its distinctive aroma is still being decoded, with over 800 coffee components interacting with the olfactory epithelium and the brain. The unique aroma of coffee hits all the attractive scents, including sweet, spicy, fruity, floral, and smoky.

That’s why a cup of coffee may not smell the same as the ground coffee produced. The brewing process, whether it’s through decoction methods (boiled coffee, Turkish coffee, percolator coffee and vacuum coffee), infusion methods (Indian drip filter coffee LINK INTERNAL and Napoletana), or Italian pressure methods (Moka and espresso), infuses the air with an aroma that tantalizes the senses. The brewing technique also determines the time the coffee is in contact with water; accordingly, certain coffee roast styles are more suitable for certain brewing techniques.

A cup of freshly brewed coffee is one of life’s simple pleasures.

When first tasting sweet and milky South Indian coffee there is a curious moment of understanding – and it is not the coffee – It is that I’ve discovered the source for the essence of those almost caramelized, creamy, coffee scented affairs, like – mousses, ice creams and candies.

South Indian Kaapi Culture

Coffee has become popular as a local and global beverage in part because people see coffee as “our own.” It becomes meaningful for many reasons, which include the attachments or fondness that we develop for the ways that Kaapi is prepared and served, the places or contexts in which we consume coffee, and the ideas and feelings associated with drinking it.

Prepared in a traditional Indian filter pot, Indian coffee decoction is brewed delicately by allowing boiling water to seep through finely ground coffee, aided by gravity, – and the pressure built by steam inside the covered top chamber. (similarly to moka pot coffee but with less pressure)

Cultural Significance of Kaapi

Coffee is an acquired taste. It is no accident that Mennell Stephen, chose to illustrate his fundamental assertion in, “All Manners of Food”, that “in humans most likes and dislikes are learned” by citing the psychologist Robert C. Bolles” idea that:

“Coffee is one of the great, marvellous flavours. Who could deny that? Well, actually anyone drinking coffee for the first time would deny it. Coffee is one of those things that [have been] called innately aversive. It is bitter and characterless; it simply tastes bad the first time you encounter it. By the time you have drunk a few thousand cups of it, you cannot live without it. Children do not like it, uninitiated adults do not like it, rats do not like it; nobody likes coffee except those who have drunk a fair amount of it, and they all love it.”

That initiation into coffee inevitably takes place within the context of family, so that our taste in coffee is, in reality, a taste for coffee as it is blended, roasted, prepared and served within that community.

Consequently coffee can become a sensory evocation of one’s membership of a social grouping – simply a shared taste.

Kaapi is not just a beverage, but holds a full dabara (or davara, a metal cup) of cultural significance. It has been a part of South Indian households for generations and is deeply ingrained in the daily routine and lifestyle of the people. It is shared as a sign of hospitality and is considered an essential part of social gatherings and festivals. It symbolizes the age-old Indian tradition of treating guests as gods, signifying that their presence is valued and respected.

Historian Ananthanarayanan knows, that filter coffee is a very integral part of south India. The bride and groom families could fight and even call off a wedding over coffee. A weak and watery coffee was what the proverbial sammandhi sandai (anywhere between a mild argument to a full-fledged war between the families of the bride and the groom) would start with.

Coffee was a big deal in my family, especially in my mother’s family. They moved to Madras from Thanjavur in the fifties and brought with them a passion for coffee along with a propensity for intellectual pursuits, politics, lengthy discussions on philosophy as well as all manner of public affairs…It seemed to me as a child visiting my grandparents that there were always tumblers of strong delicious coffee, available at all times of the day; sweet enough for a child sometimes and at other times strongly brewed and dark like some sinister potion that would at once bestow special powers on the drinker…

Nirmala Lakshman, explains in her book,, Degree Coffee by the Yard.

While Kaapi’s popularity soared across the country over the 20th century, it also migrated outwards – to Malaysia and Singapore. Known as kopi tarik, the drink was introduced by roadside stalls run by Indian migrant communities.

Iconic Indian filter Kaapi

Filter kaapi – scorching, strong, sweet and topped with a bubbly froth

It isn’t just the beans that make South Indian filter coffee so unique, it’s a combination of how those are roasted and ground, brewed, and served. This coffee rituals, along with their impenetrable sentiment, are passed down within families. R.K.Narayan’s essay in My Dateless Diary tells about his initiation in the path of filter coffee.

I could not help mentioning my mother who has maintained our house-reputation for coffee undimmed for half a century.

She selects the right quality of seeds almost subjecting every bean to a severe scrutiny, roasts them slowly over charcoal fire, and knows by the texture and fragrance of the golden smoke emanating from the chinks in the roaster whether the seeds within have turned the right shade and then grinds them into perfect grains;

everything has to be right in this business

, says the celebrated writer from Mysuru. That’s exactly how scrupulous coffee lovers are, from selecting the right quality seeds to preparing the decoction. Filter coffee is an indispensable part of South India and the preparation can take up to 30 minutes, some say even hours. As scalding hot water meets the ground coffee, a dance of aromas ensues. The gentle bloom, as the kaapi grounds release carbon dioxide, accompanied by a fragrant burst that hints at the flavors to come. The brewing is not fast, but excruciatingly slow, as the coffee drips idly to form the ‘decoction’. A strong black fluid.

South Indian filter coffee comes in many forms and is known by various names, Decoction coffee, Kaapi, Mylapore Filter Coffee, Madras and Kumbakonam Degree Coffee. The town of Kumbakonam in Thanjavur district Tamil Nadu, typifies the culture and ethos of the people of the district and hence the filter coffee has acquired the name of “Kumbakonam Degree Coffee” aka “Kumbakonam Filter Coffee”.

At some point during the 19th century, South Indians began to adopt coffee drinking, and develop it with their own style. The nuances that go into making the perfect filter kaapi are still a topic of contention among connoisseurs, conservatives and plain coffee-lovers alike. Cultural diversity in India enhance debates and discussions around coffee:

Black – kali kaapi? Sweet? Cream ? Milk? Chicory?

While some contest over the brand or purity of the coffee powder, milk – connoisseurs debate over the dilution as well as the quality and thickness of the milk that goes into its preparation – known coffee joints get the milk sourced from exclusive milk cows!

Degree Coffee

Milk for filter coffee should be undiluted – a cultural rule. Dairy farms use a lactometer to check if the milk is indeed undiluted and fit for filter coffee. The lactometer was confused with the thermometer by those who did not know better. This gave rise to the term ’degree coffee’ in the Cauvery delta region, where local dairies supplied to coffee houses.

What is degree coffee? Deepa Harishankar asks here

… the spirit of old Madras leaps out of unexpected corners… It rises from hot, freshly ground ‘degree coffee’ (an import from Kumbakonam) in roadside tea stalls, made with expert hand movements that draw the attention of passers-by…

Yet another rendering explains, that the first decoction drawn with minimal water and maximum essence – first degree. The second decoction that is brewed after the first process is completed is reserved for children and people you don’t particularly like – second degree and the third degree – you cannot even call coffee any more. However, in less affluent households coffee would be infused for a second or third time from the same initial load and would be called the second or third degree coffee respectively given its lower strength and taste profile.

A possible derivation for the term also comes from the chicory used to make the coffee. The South Indian pronunciation of chicory became chigory, then digory, and finally degree.

Another explanation could be that coffee was mixed by pouring it from one cup to another cup, it has to be poured at a certain angle or “degree” for best taste. This method of mixing coffee or tea is also called “meter coffee/chai”.

Purists argue, that the milk and chicory masques flavor notes and profiles – unsweetened kali kaapi is the connoisseurs credo. The complex symphony of aromas intensifies, with each note revealing a layer of the coffee’s character. The steam rising from the milkless cup carries with it a medley of scents – nutty, chocolaty, fruity, or floral – each one a reflection of the beans’ origin, roast, and preparation.

A faction of filter coffee fanatics swear that sprinkling a few granules of sugar to the coffee powder makes a thicker and flavorful decoction. To sweeten it with honey or jaggery (an unrefined cane or date juice affair) was an early choice, replaced by the advent of processed sugar later.

Some are pulled by the aroma of Arabica, Robusta or blended coffee. Indian coffee may include also cardamom, clove, pepper and nutmeg. Or be mixed with 10-20% of chicory.

Chicory (Cichorium intybus)

The roasted and ground root of the endive plant is commonly added to South Indian coffee blends to enhance its flavor and aroma – giving it a slightly bitter and earthy note – a characteristic taste that South Indian coffee lovers look for.

According to Antony Wild, author of Coffee: A Dark History, the use of chicory became popular in France during Napoleon‘s ‘Continental Blockade’ of 1808, which resulted in a major coffee shortage.

The practice made its way to the French colonies, like Louisiana, Café Du Monde in New Orleans still serves chicory-blend coffee in their Café au lait,milk coffee.

The French colonial provinces in India at the time were scattered around the south-eastern coastline, with their capital at present-day Pondicherry, a Union Territory of India adjoining Tamil Nadu.

In Europe, chicory was widely used as a coffee extender during economic crises such as the Great Depression in the 1930s and during WWII. As chicory is less expensive than coffee, mixing it makes the blend more economical. Chicory is traditionally added to coffee in Indian, Spanish, Greek, Turkish, Syrian, Lebanese, Palestinian and North-American cuisines.

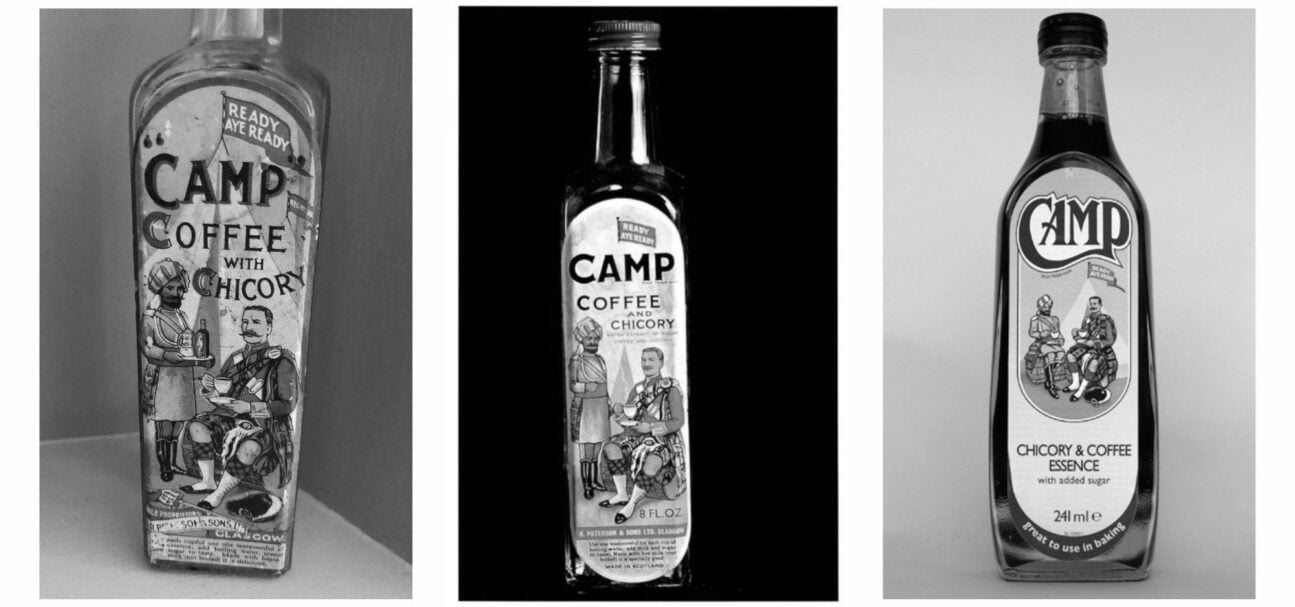

Camp Coffee, a 4% coffee and 26% chicory essence, has been on sale since 1885 and is said to have originated when the Scottish Gordon Highlanders requested a coffee drink that could be brewed up easily by the army on field campaigns in India. “You can dispense it from the jar, and preparation was usually done by mixing and heating with milk, so it was likely consumed as a relatively sweet and soothing drink. In some senses, this would have been even easier than making tea (no teabags having been invented at that time).” says Jonathan Morris, Research Professor of Modern European History at the University of Hertfordshire and author of Coffee: A Global History.

By the late 18th century, camp coffee had been introduced to South India.Popular among soldiers, the beverage was sold in military hotels and coffee houses in Madras, leading to the cultivation of chicory in the Western Ghats by 1860.

At some point in the mid-20th century, the label was edited, removing the tray – and thus, presumably, the implication of servitude – from the Sikh figure’s hands. Instead of holding his tray, the servant was just standing beside the Scottish soldier. Again, the label was changed, and now both soldiers are sitting together at a table. It is widely believed that these changes were made in order to mitigate the colonial connotations of the label.

Others believe that chicory was utilized for its medicinal properties, and its use in kaapi reduced the caffeine intake. Chicory however, leaves a bitter aftertaste that can be countered by the addition of milk and sugar.

One more reason chicory is used, I learn, is because it contributes to the clogging effect, drawing out the brewing even longer – resulting in a more mellow taste, despite its own inherent bitterness.

A caffeinated History: The ancestors of the Indian kaapi maker

The basic idea of filtering coffee using cloth or – a sock is evident. The sock filter is still used in a Japanese style of coffee preparation and is also popular in SE Asia (Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore..)

Rakesh Raghunathan, a food historian based in Chennai, recalls his grandmother’s technique of making Decoction kaapi using a cloth filter, he tells The Better India.

Way before all these electronic coffee machines made their way into our homes, my paati (grandmother) would painstakingly make her own coffee powder and then the decoction. First, she would roast the coffee beans. Next, she’d grind them in her hand grinder till she achieved the desired level of coarseness. Then, she’d collect this power and heap it into a thin muslin cloth… She’d pour hot water and the decoction would percolate. This would then be used to make the perfect cup of filter kaapi,

Channi coffee is made by boiling the powder in a pan and filtering it using a channi, a tea strainer.

If the coffee has a lot of grit or coffee powder in it, then add a muslin cloth over the channi or use a coarser grind.

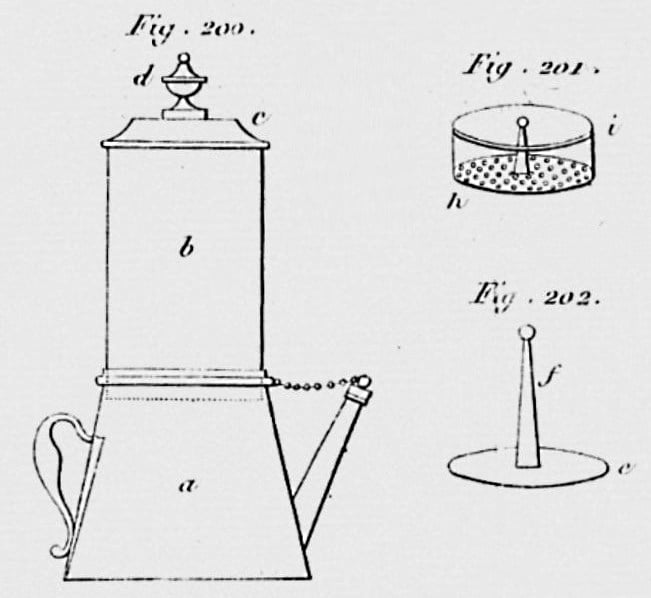

French drip devices emerged from the earlier coffee biggins (1780) where cloth filters would be fully inserted into the pot for steeping instead of drip filtering.

Drip coffee pots don’t use paper filters but a permanent filter featuring many small, round, drilled holes made out of (enameled) metal, ceramics or porcelain.

De Belloy coffeemaker, the grandfather of the Indian filter coffeemaker

The invention “French drip” coffeemaker around 1800 is attributed to Archbishop De Belloy (Grimod De La Reynière’s Almanach). Shortly afterwards, Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford, the prolific inventor, worked on a drip coffee pot as well as on a percolator for making coffee. Another inventor, Parisian tinsmith Joseph-Henry-Marie Laurens, also worked on the percolator at around that time.

An alternate history of the De Belloy drip coffee maker identifies a number of inventors and manufacturers who contributed to this innovation. A nephew of Archbishop De Belloy; the proprietor of a popular coffee shop in the Palais Royal; a pharmacist, chemist and inventor from Rouen named François Antoine Henri Descroizilles (1751-1825), played a role in its invention. See the post “Elevator to Espresso” at The Black Blob Spot for a full exploration of this story.

Drip coffee: The metal South Indian coffee filter

The inventor of the South Indian coffee filter is lost to history – as Doctor mentions here, the one in use today might well be a homegrown, practical, metal version of the foreign percolators introduced to India.

Most households have a stainless-steel coffee filter, passed down within families, and shops sell freshly roasted and ground coffee beans. The stainless steel or brass percolator is divided into two halves, with a plunger, and an airtight lid. The bottom of the upper half is pierced with small holes, through which the coffee drips into the container below.

South Indian drip brew process uses finely ground powder, so the water stays in contact longer.

The finer the grind, the more flavor gets extracted and brewing time increases.

The preparation of South Indian coffee with a stainless-steel coffee filter

The upper cup is loaded with fresh ground coffee. The grounds are gently compressed with the stemmed disc into a uniform layer across the cup’s pierced bottom. With the press disc left in place, the upper cup is nested into the top of the tumbler and boiling water is poured inside. The lid is placed on top, and the device is left to slowly drip the brewed coffee into the bottom. The decoction is then added to milk and sugar.

Similarly constructed percolators find mention in cookbooks like in Culinary Jottings for Madras, which dates as far back as 1878, At the end of this cookbook Colonel Kenney-Herbert has three pages “On Coffee Making” and the method he describes, from careful selection of beans, to slow roast to the type of percolator used is almost identical to how filter coffee is made today. In fact, he suggests going even slower by pouring in scalding hot water in teaspoonfuls:

“The slower the water is added, the more thoroughly the coffee will become soaked, and, the dripping being retarded, the essence will be as strong as possible.”

This decoction, was made in advance to be added to hot milk or water. Other British writers took this even further. Flora Annie Steel and Grace Gardiner in their Complete Indian Housekeeper and Cook (1888) even recommend steeping the coffee in cold water overnight, and only then bringing it to boil before straining and storing for up to a week.

Today modern semi automatic South Indian filter or decoction coffee makers are produced – as fully automatic or manually operated machines. With a coffee decoction tank capacity of about 4 liters. Dispensing 6 cups per minute and brew up to 3000 cups of coffee in a day. This semi automatic South Indian filter coffee makers are used in Hotels, Canteens, Restaurants, Coffee houses etc.

Traditional serving style of filter kaapi

The traditional filter pot follows a pour-over style of filtration. Indian Decoction coffee is prepared by first bringing water to boil and after the slow filtration process, the concoction is poured into a metal cup, known as a davara, which is served inside a stainless-steel tumbler.

As a teenager, the smell of freshly filtered coffee was my cue to get out of bed. As I shuffled down the stairs, my mother would be halfway through making coffee in her gnarled saucepan. Milk boiled first, to which a thick decoction (the coffee extract in the filter) was added – but never boiled – followed by sugar.

Arati Menon

Norai – the froth

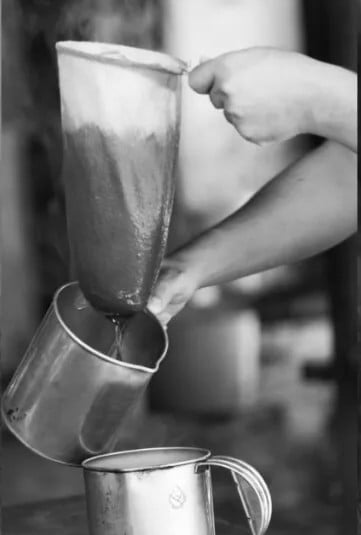

The liquid was then deftly and repeatedly juggled between saucepan and mug to give it extra foam (norai) – this bit of food theater is entrenched in kaapi tradition .

At many coffee houses you can see it poured from a meter high. Arati Menon writes.

Coffee is typically served after pouring back and forth between the dabara and the tumbler in huge arc-like motions of the hand – by ‘pulling’ the coffee – This serves the purposes of: mixing the ingredients (milk and sugar) thoroughly; cooling the hot coffee to a sipping temperature; and most importantly frothing–aerating the mix without introducing extra water and foaming milk.

An anecdote related to the distance between the pouring and receiving cup leads to another name for the drink, “Meter Coffee“. The unique serving style adds to the overall experience of enjoying a cup of Kaapi.

The creamy, frothy top layer coats your tongue, enveloping you and making you feel cozy to the last drop.

Indian coffee – Indian Chai

Don’t ever make the mistake of ordering a chai in South India… for South India is the land of coffee. says Allen Stewart Lee must have been in the North, when having this experience.

“I finally understood the Indian cup”, Every religion has its sacred brew. Christians and Jews have wine; Buddhists, tea (said to have grown from Siddhartha’s eyelash); Muslims, coffee.

For Hindus it is milk from the sacred cow.

All that had puzzled me was now made clear: the man who had criticized a coffeemak-er for “putting water in his milk;” the huge vats of reducing cream used to make “special” coffee; the puzzled looks of vendors when I had asked for my cup black.

Every foreigner in India has his or her moment of enlightenment. This was mine. He was my guru.“and so, Baba,” I said, “that is why the Indian puts too much milk in his coffee?”

“Yes, my son.” He clicked his tongue disapprovingly. “But you should drink only tea. Coffee is a bitter liquid that produces a rumbling of the bowels.”

Part of the Indian coffee culture is how Kaapi is prepared and drunk domestically and in coffee houses, roadside dhabas darshinis and hotels. India is a nation typically renowned for its tea. Grand tea estates and blossoming coffee plantations cover hill stations across both northern-east and southern Bharat. Chai wallahs are found on corners across India, selling small cups of tea from roadside stands and carts. If you order coffee with them (if they sell any at all), you’re more likely to be served a sad cup – made with or without powder milk and Bru or Nescafe – the popular instant coffee brands in India, that can contain 20–49% of chicory.

We had a literally bitter experience – Don’t allow yourself to be lulled into a false sense of security regarding all the wonderful coffee that is grown in India.

There are some truly awful concoctions out there – tasting like a saturated solution of castor oil and tamarind seed extract – You could be the next victim.

While coffee remains a beverage mostly consumed at home across India, the southern states of Kerala, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu are abundant with street-side coffee stands, darshinis, much like the tea stands throughout northern India. This coffee wallahs serve Kaapi in all its glorious goodness. Mostly, the concoction is served with a dose of milk and sugar, frothing to the rim. Taking a quick coffee, standing and making room for the next customer is interestingly also found in traditional Italian bars.

This coffee ritual is so important that a common afternoon greeting in Bangalore is:

“Coffee aitha?”

Had your coffee?

History – Tracing the Origins and Expansion of Coffee Cultivation in India

The Legend of Baba Budan

Legend has it that a wandering Sufi mystic, Baba Budan, smuggled alive coffee seeds from Mocha to India when he returned from the Hadj pilgrimage to Mecca. While traveling home through the port of Mocha in Yemen, Baba Budan enjoyed kahwa (Arabic for coffee) in Mocha and learned as much as possible about the beverage. As well as the process from bean to cup. He procured seven seeds – seven, a sacred number – which he hid in his beard and in his walking stick. Some say he tied a few to his belly with a cloth and smuggled the cherries out of Arabia. Near the caves where he and his followers had settled, Baba planted the fruits and grew the first Arabica plants in Mysore (today’s Karnataka) on the slopes of the Chandragiri – Giri meaning a hill.

Today his shrine sits on top of one of the highest peaks, which has been named after him: Baba Budangiri.

Etymology of the word Coffee

Coffee made its way into Indian lives in the early 17th century, as a part of Mughal culture and South Asian cuisine, and it had a slow comeback under various colonies. Coffee found its way into different languages as it spread to numerous countries via Dutch, British and French companies. The word and pronunciation were slightly adapted to better suit their natural sounds. Coffee is one of the world’s most commonly used words, infused with slight semantic variations according to each language and culture: Kaapi, café, kaffee, kopi, caffé, kafei, kohi…

Kaapi is a phonetic rendering of the word coffee.

Hindi कॉफ़ी for kofee is a videshaj (exotic) word for coffee. In Kannada Kāphi ![]() or kahi kashaya literally translates to bitter concoction. In Tamil it is called காபி Kāpi, in Malayalam കോഫി ; Kēāphi, କଫି [ସମ୍ପାଦନା] in Odia and in Telugu Kāphī

or kahi kashaya literally translates to bitter concoction. In Tamil it is called காபி Kāpi, in Malayalam കോഫി ; Kēāphi, କଫି [ସମ୍ପାଦନା] in Odia and in Telugu Kāphī![]() .

.

The lush-leaved trees and their precious berries, which range from green to bright red when mature – originate in East Africa, most likely Ethiopia, where the Kaffa Kingdom may have baptized the plant with its name – قهوه qahwah. This etymology has been disputed, though, since the Oromo people of Ethiopia refer to the coffee berries as bun. Instead, many argue that the Kaffa province was named for the beans. Other possible derivations for qahwah include quwwa (the Arabic word for “power”), and kafta, the drink made from the khat plant (Pendergrast 2010). Another etymology suggests that coffee comes from Arabic, meaning “dark color,” – originally used for strong wine that was made from the pulp and husks of coffee beans.

Smell the history of coffee in its entirety – starting with its roots and flourishes

All About Coffee, by William Ukers. 1928. CC0

Coffee comes from a plant belonging to the genus Coffea of the Rubisceae plant family. India’s coffee culture dates back to the sixteenth century, when the first seeds arrived with Arab merchants, likely originating in what is now Ethiopia (or perhaps Yemen), where legendary goats were particularly frisky after eating the berries.

The mythical origins of coffee are steeped in legend and topped with a creamy dollop of speculation. From the Arabian Peninsula, there is mention of roasting and brewing coffee in the 15th century. Later, it was believed that coffee was used by Sufi saints to keep themselves awake during their religious rituals. By the 16th century, coffee drinking had spread to the rest of the Middle East, Persia, Turkey and North Africa.

Coffee was a thing of beauty for Islamic consumers. The coffee cup was often likened to a tulip, holding the passionate heart of a lover. The black-colored coffee beverage was equated with mesmerizing kohl-rimmed eyes. Marvelous jewel tones of peacock and the subtly changing hues of dusk were also attributed to the beverage.

Walter Hakala. 2014.

Walter Hakala’s description bears direct correlation to the Turkish coffee or Arab preparation method where coffee grinds boiled in water – with an Ibrīq, a little copper pan with a long handle – were not filtered away but instead allowed to settle at the bottom of the cup, resulting in an iridescent oil film on the top of the cup. In addition to the dried, roasted, and ground coffee beans, recipes variously called for using the leaves and fleshy berries of the coffee plant, which were steeped and brewed in hot water, Walter Hakala tells.

The foam of the Turkish coffee is so thick a camel can walk across it.

Ottoman saying

The History of Coffee Cultivation & Commercial Plantations in India under various colonies

Coffee isn’t indigenous to India. Tales of wild coffee in the Western Ghats before plantations were established exist – was it the coffee plants in the Baba Budan range that thrived unattended and continued to grow wild, even as the East India Company began looking at cultivating pepper and coffee as plantation crops in India?

Coffee historians believe, the Dutch brought coffee to India around 1680, growing coffee in the Malabar region. The British Journal of Mythic Society VII claims that in AD 1385, Emperor Harihara II of Vijayanagar (now Mysore) ordered that all imports for Peta Math enter tax-free in “return for coffee seeds,” putting the Dutch claim to primacy in doubt. Were the Vijayanagar seeds roasted or not roasted? That would make all the difference between drinking coffee and growing it.

Clear is that the Dutch had a productive and growing trade in coffee outside of India. Successfully growing coffee in Batavia (today Jakarta), on the island of Java in what is now Indonesia, and soon expanding the cultivation of coffee trees to the islands of Sumatra and Celebes (today Sulawesi).

Alivardi Khan, the Nawab Nazim of Bengal, was of Arab and Turkman descent and ruled Bengal from 1740–1756. Known as a diligent ruler, coffee and food were the two biggest pleasures of his life. Siraj ud-Daulah, Khan’s grandson and successor, faced threats from the British, and the courtly coffee culture swiftly dissipated, along with Bengal’s fortunes. When Bengal lost the decisive Battle of Plassey in 1757, the East India Company took control of the region, and slowly coffee vanished from public consumption and consciousness.

The rise of the East India Company, which was the primary agent of British control in India, marked the end of the subcontinent’s dominant coffee culture.

Nilosree Biswas

As the East India Company slowly spread across hill stations and the rest of India, coffee plantations went along with them. The earliest coffee plantations in Chickmagalur (Chikkamagaluru) and Coorg were established in the late 19th century. An enterprising European, by the name of Thomas Cannon, started growing coffee near Chickmagalur. In 1843, Fredrick Green took to it in Manjarabad. Both Cannon and Green are considered pioneers. Kannada folklorist Dr. H.L. Nagegowda, in his book, Bettadinda Battalige – Coffeeya kathe (Story of Coffee), makes references to M.H. Stokes and J.H. Jolly of Parry & Co. trading company. Jolly saw the potential of coffee beans growing in the plantations of Chandragiri and had a petition sent to the Mysore government in the adjoining state of Karnataka for 40 acres of land to grow coffee.

In 1855 R.H. Elliot raised his plantation at Bartchinhulla, south of Manjarabad. His first book, The Experiences Of A Planter In The Jungles Of Mysore, was published in 1871 in two volumes. These books are also an account of the hardship, physical fatigue, and loneliness that come with a plantation life, starting from marking the land, leveling the ground, planting the crop and raising shade trees, to cutting, pruning, manuring, and packing the beans for overseas markets. Using illustrations, pencil sketches, and maps, they provide detailed information about growing coffee, cinchona, and cardamom.

“Coffee was less important to the British than tea”— the coffee trade in the 18th and 19th centuries was mostly the domain of the French and Dutch. “The one area where coffee was to become important in the British Empire was Sri Lanka, known colonially as Ceylon, the island that the British captured from the Dutch in the early 1800s,” says Professor Morris. In 1902 a wave of coffee leaf rust hit India and Sri Lanka and devastated the coffee plantations. The British took this as an opportunity to replace them with tea or robusta coffee.

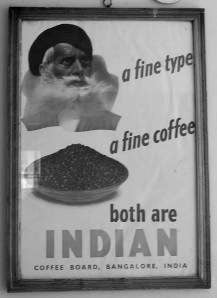

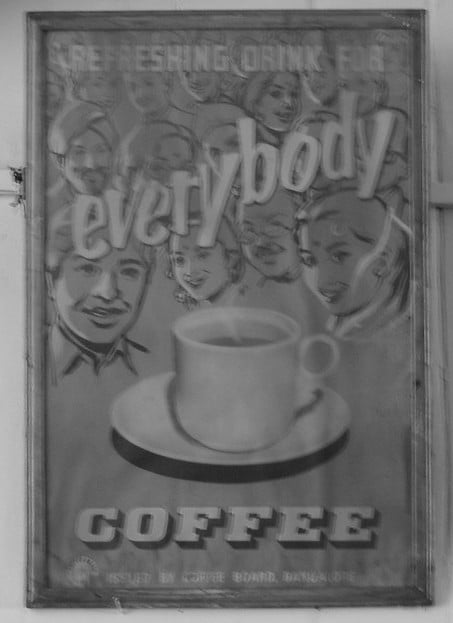

Indian Coffee Board

However, the industry suffered a huge setback during the Great Depression, and the Indian government stepped in by setting up the Coffee Cess Committee (1907) and later the Indian Coffee Board.

In 1942, the government decided to regulate the export of coffee and protect small and marginal farmers by passing the Coffee VII Act, under which the Indian Coffee Board was established and operated by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry of the government of India to promote coffee production in India. Initially, the Board provided funding to exporters, pooling of coffee produce was the norm in the initial decades of independent India. When World War II sealed export routes, the board began to buy coffee from planters and took upon itself the responsibility of marketing the produce. In the post-liberalization era, from 1995 onward, the government allowed coffee planters to market their own produce rather than sell it to a central pool.

Today, the Indian Coffee Board is a government-controlled organization charting the wellness of this commercial crop. It conducts coffee exhibitions and trade fairs to create awareness about the rich Indian coffee among consumers in domestic and international sectors. It is conducting coffee research, giving financial assistance to establish small coffee growers, safeguarding working conditions for laborers, and managing the surplus pool of unsold coffee. The Board mainly focuses its activities in the areas of extension, development, market intelligence, external & internal promotion for coffee. There is an informative Coffee Yatra Museum in Chikmagalur’s coffee board.

Sip, savor, socialize: Coffeehouses in India

Throughout the centuries, coffeehouses have played a pivotal role in society as spaces for gathering, idea exchange, and social interaction. These charming establishments, filled with the irresistible aroma of fresh coffee, have attracted people from different cultures and backgrounds, creating a unique environment of conviviality.

In his writings Sheik Abd-al-Kadir states:

“No one can understand the truth until he drinks of coffee’s frothy goodness.”

Qahwahkhanas – Mughal Coffeehouses in India

An early mention of coffee in India comes 1616, from English Reverend Edward Terry, writing about his time in Mughal South Asia. He recorded from the court of emperor Jahangir:

Many of the people there [in Mughal India] who are strict in their religion drink no wine at all, but they use a liquor more wholesome and pleasant, they call it coffee; made by a black seed boyld in water, which turns it almost into the same colour, but doth very little alter the taste of the water: notwithstanding it is very good to help digestion, to quicken the spirits, and to cleanse the blood.

Medical treatises of the time provided recipes for preparing flavorsome ginger, cinnamon, and cardamom coffee. Rosewater and sugar-candy were also added to the delicacy. In Ottoman times, the drink was served thick, bitter, near-boiling and not sweetened. Mostly cardamom was added, apparently opium and hashish were also stirred in. The Sultans used to enhance kahwa with the aroma of exotic spices like saffron and even ambergris (dried whale vomit).

The German adventurer Johan Albrecht de Mandelslo wrote about his travels in the east through Persia and Indian cities such as Surat, Ahmedabad, Agra, and Lahore in a memoir titled The Voyages and Travels of J. Albert de Mandelslo. In 1638, he describes drinking kahwa (coffee) to counter the heat and keep oneself cool.

The Hindu and Muslim aristocracy in Emperor Jahangir’s court indulged in coffee. Arab and Turkish traders who had strong trade ties with the Mughal Empire not only brought coffee but also other valuable items, including silk, tobacco, cotton, spices, gemstones, etc., from the Middle East, Central Asia, Persia, and Turkey. In his work Travels in the Mogul Empire (1656–1688), Francois Bernier, a French physician, refers to the large amount of coffee imported from Turkey.

By the 17th century, coffee had become an important part of everyday life in the Mughal cities. It was served in public spaces called qahwahkhanas (coffee houses), and there were many around Delhi’s Red Fort, especially in the Chandni Chowk area. Historian Stephen Blake, in his 1991 work Shahjhanabad: The Sovereign City in Mughal India, 1639–1739, describes

vibrant coffee houses as places where poets, storytellers, orators, and those “invigorated by their spirits” congregated for poetry recitals, storytelling and debates and long hours of playing board games.

Coffee houses of Shahjhanabad, like those of Isfahan and Istanbul, accelerated the rise of a culture of consumption and a thriving food culture, with residents frequenting snack sellers offering savouries, naanwais baking bread, and halwais specializing in confectionery.

In 18th-century Mughal Delhi, In her essay Spilling the Beans: The Islamic History of Coffee, food historian Neha Vermani describes, that the Arab ki sarai, an inn run by Arab traders, was famous for preparing sticky, sweet coffee.

British Coffeehouses in South India

Coffee houses or clubs, came up in Calcutta in 1780, only to serve the British. Soon after, John Jackson and Cottrell Barrett opened the original Madras Coffee House, which was followed in 1792 by the Exchange Coffee Tavern. The enterprising proprietor of the latter announced he was going to run his coffee house on the same lines as in London, by maintaining a register of the arrival and departure of ships, and offering Indian and European newspapers to read.

In Those Days There Was No Coffee – British influence on local culture

Indian historian and author, AR Venkatachalapthy, writes in his 2006 book In Those Days There was No Coffee: Writings in Cultural History, that there was no escaping the physical effects or symbolism of coffee in late 19th century British India.

Drinking coffee, it appears, was no simple quotidian affair. Much like history, the nation-state, or even the novel, coffee too was the sign of the modern…

Venkatachalapathy also noted that many believed, the drink would lead to “westernized behavior” and “addiction”. He explains that the phrase, – In Those Days There Was No Coffee –, was used by mid-20th century Tamil writers like Va. Ramaswamy Iyengar and U.V. Swaminatha Iyer as a way to describe the period from 1910 to 1915, when modernity was defined by British-influenced innovations like tea and coffee drinking that started to make their way into middle class South Indian households.

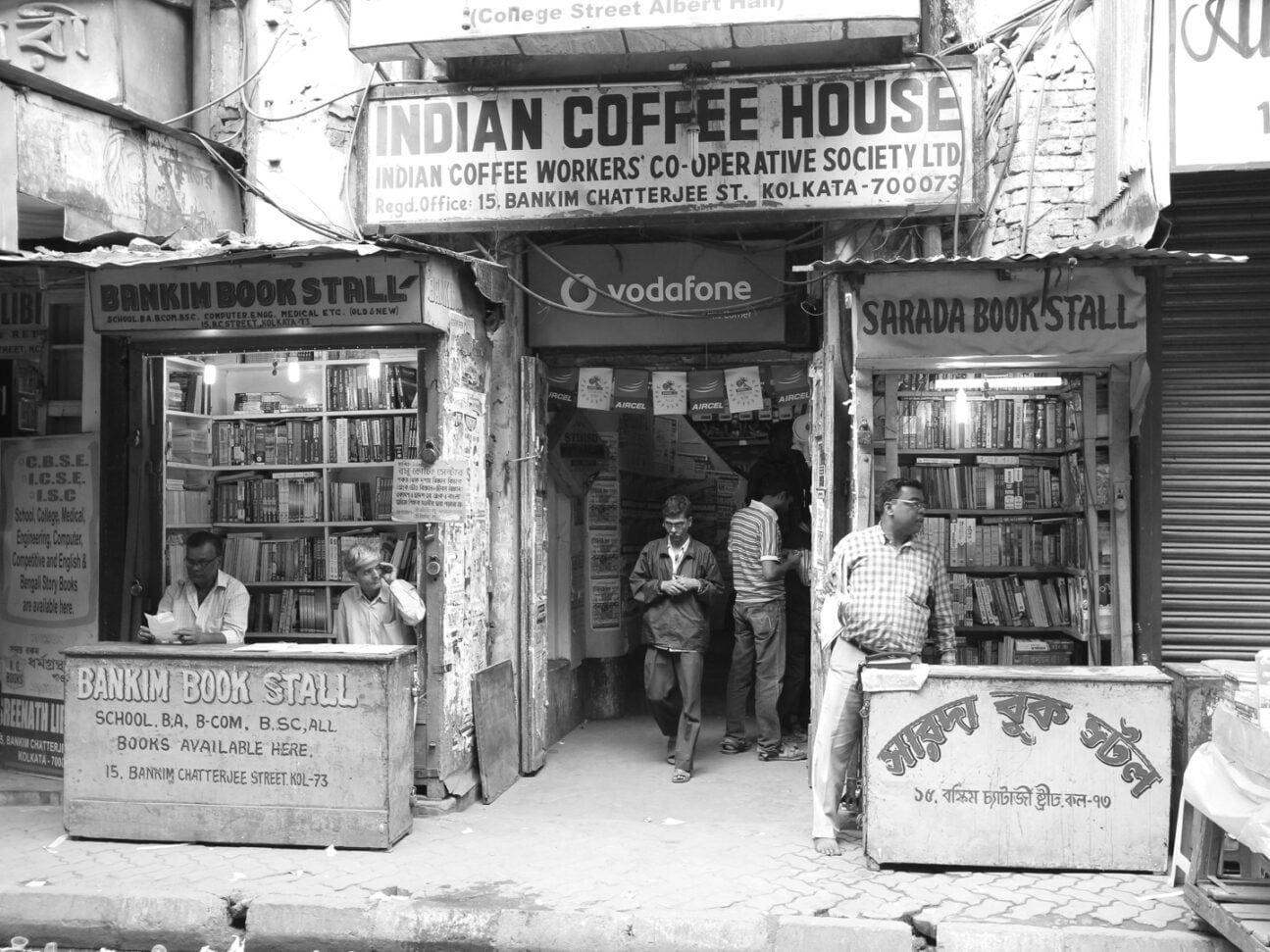

The Indian coffee house – revolutionary politics and a different way to do business

Coffee is the elixir that drives away weariness. Coffee gives vigour and energy.

Advert for coffee in south India in the 1890s

The first Indian coffee house was opened by the Coffee Cess Committee in Churchgate, Bombay [Mumbai], in 1936, and then, across the country. With the aim to provide a space for the country’s elite to meet and educate South Asians about the benefits of homegrown coffee. The chain soon became popular, with more than 70 outlets by the late 1940s. Although successful for many years, the Coffee Board’s business and policy changed in the mid-1950s and closed down all of their outlets.

At this point, Communist leader A K Gopalan, encouraged coffeehouse workers to start a cooperative and take over the business from the Board. In 1957, the brand was established as a worker cooperative and renamed the Indian Coffee House (ICH).

Its first outlets opened in Bangalore and New Delhi. Today, there are over 400 Indian Coffee House outlets across the country, managed by 13 cooperative societies. Since then, every worker at the Indian coffee House is a co-owner.

Indian tea – and coffee places have since served as newsrooms and chatting corners for people from all walks of life.

People debated literature, art, social welfare and the changing face of Indian society in coffeehouses. In his book, The Brothers Bihari, Thakur writes,

Indian Coffee House was where I first heard words like Fuehrer and fascism first, words like proletariat and bourgeoisie, like Comintern and Nato and sarvahara and samajvaad, satta, samrajyavaad and taanashahi.

So powerful was this “public living room” that the scent of scandal brewing here during the Emergency (popular discontent against Indira Gandhi peaking post-1973) wafted into the corridors of power, leading to a temporary shutdown of the Indian Coffee House in Delhi. Still, this Coffee House is a spot where you find people from all walks of life coming together over a cup of coffee.

You can find families sharing their anecdotes, a group of old men discussing political matters of the day with newspapers on hand, and white-collar workers sharing their daily dose of finances. It still remains one of the places where you can expect a new philosophical idea to develop at any time.

In India, ‘a lot can happen over coffee’.

Certain branches of this institution have acquired near-legendary status as hot spots where opinions were kept forward, ideas were brewed, and the essence of living in a free country was felt.

In the legendary College Street Coffee House in Kolkata, it was not uncommon to see the likes of Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Sunil Gangopadhyay and many others engaged in animated discussions adda, with other customers eavesdropping from nearby tables. This has even been immortalized in a famous song by Manna Dey titled ‘Coffee House’er shei adda’ta aaj aar nei’ (That Coffee House is long gone now).

It was regularly frequented by many Bengali scholars, including Rabindranath Tagore, while Shimla’s ICH was one of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s favourite coffee places. In Allahabad’s Coffee House located in Civil Lines, the Urdu poet Firaq Gorakhpuri (who ironically taught English at Allahabad University) was known to hold forth for hours on all kinds of issues. In Patna’s Coffee House located on Dak Bungalow Road, Hindi writer Phanishwar Nath Renu would visit regularly.

Across many cities and towns throughout Bharat, the India Coffee House is something of an omnipresent eatery. Unassuming, unpretentious, efficient and reasonably priced. The crisp white uniforms with a belt and a turban (with red green or golden paraphernalia attached to them) of the waiters adds to the bygone charm.

At the Indian Coffee House coffee tastes the same old drink and food of nostalgia.

In the tapestry of Indian coffee house culture, the threads of coffee run deep. This aromatic brew has emerged as powerful unifier, bringing people together, transcending differences, and fostering a sense of community in the hustle and bustle of life.

We let food and filter kaapi be our key to understanding coffee history in India’s Ancient South. Eating traditional food, connecting with the land, listening to the stories and creating our own unique experience, what better place, then a coffee house for that. The South Indian culinary repertoire reflects the cultural diversity of Bharat, a melange of flavors from different parts of the country and showcases centuries of cultural exchange with the far corners of the world. A kaapi for breakfast, or after meals is a very much south Indian delight.

Every bite of South Indian food bursts with delicious flavor: coconut, curry leafs, peppercorns, cardamom, tamarind and chilies.

The cultural, emotional, and sensory aspects of the human experience are reflected by traditional food as an effective metaphor in literature. This sonnet from Food connoisseur in Symphony of Tastes, describes the dishes from the menu of Indian Coffee House, Alleppey, Kerala, India:

Filter Coffee’s Wake In the heart of Alleppey, where stories take shape, “Filter Coffee’s Wake,” in every cup, we escape, Aromatic beans brewed, like a morning’s landscape, Indian Coffee House’s charm, in each sip, we drape.

Idli’s Tender Touch On a plate, like clouds, in a delicate cape, “Idli’s Tender Touch,” soft as an infant’s nape, With coconut chutney, a taste that can’t gape, Indian Coffee House’s delight, in every bite’s tape.

Egg Curry’s Delight In the pot’s embrace, where spices agitate, “Egg Curry’s Delight,” a rich and spicy state, With eggs boiled tender, in a curry’s rate, Indian Coffee House’s creation, we appreciate.

Vada’s Crunchy Charisma From the frying pan’s sizzle, where flavors gyrate, “Vada’s Crunchy Charisma,” on a crispy slate, With lentils and spices, it’s a taste to celebrate, Indian Coffee House’s vada, on every plate.

Masala Dosa’s Unfold In the kitchen’s warmth, where flavors reshape, “Masala Dosa’s Unfold,” with a crispy landscape, With spicy potato filling, a culinary scrape, Indian Coffee House’s dosa, in every fold, we gape.

Sweets from Kerala’s Heart As the meal concludes, in a sweet, sugary prate, “Sweets from Kerala’s Heart,” where flavors collaborate, With syrupy grace, in a dessert’s loving state, Indian Coffee House’s finale, on every palate we rate.

Whether it is for a piping hot filter coffee, or a crispy dosa, ICH’s legacy continues.

The filter coffee was made popular by the Indian Coffee House, and thousands of Indians tasted their first espressos and cappuccinos at Café Coffee Day (CCD). As the coffee market opened, entrepreneurs like VG Siddhartha set up the chain with the first Café in Bangalore in 1996. It became an instant hit among young working people, students and corporate executives.

Global coffee chains both home-grown and foreign (Barista, Brewberrys, Costa Coffee, Lavazza, Starbucks) transformed the concept of coffee houses in India with free WiFi, air-conditioned spaces and plush ambiance, giving way to a new kind of coffee experience. Cities have embraced this new trend and boast dozens of cafés and eateries where friends can gather and socialize over a cup of coffee. The ambiance varies from squashy-couch comfort to artsy to upscale, depending on personal preference and budget. These days there is coffee shops located in train stations, hospitals, airports, shopping malls, and other public spaces and institutions.

Indian café culture has introduced coffee to many, and even in traditional coffee-drinking regions it has brought more variety to the cup. Baristas serve Italian espresso, cappuccino, filter or decoction coffee, and more to people who had far fewer options before. Coffee drinkers are getting more aware of quality, tastes and flavors and the value of Indian coffee. Consumption is steadily rising, not only in the south, but increasingly in tea-loving North India where coffee culture has become trendy or fashionable.

A tiny dabara of kaapi in South India has much history behind it – strong and rich.

CC BY 4.0

We drunk in the centuries-long history of Kaapi. Visiting South India, we have often been invited to share a coffee (and chai), by friendly and curious locals. Having a coffee means sharing stories and being part of a deeply cultural ritual. It has quality standards, tradition and history.

We brew some intriguing tales with the communities of South India, at the estates, farms and home stays, chatting with – owners and labourers –

Learning from the people at the coffee board, the Central Coffee Research Institute (CCRI), at Coffee Curing Works, the stalls and small coffee establishments at the market or the coffee lorry drivers at loading stations around Chikkamagalore, Baba Budanagiri, Mysore, Cardamon Highlands, Nilgiris, Coimbatore, Kozhikode, Palakkad, Idukki, Kodaikanal, Tirupati, etc.

All of them cultivating a love of kaapi, hard work, and kindness. These pride coffee communities not only want to understand the fruit and business, but themselves too. Amidst the variety of India there is a deeply felt sense of belonging which we heard in all the stories that were told to us.

Coffee is essentially a matter of personal taste and heritage – enjoy your davara of filter kaapi – whatever your preferences.

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

Thank you Klaus Langrock for proofreading.

The history of coffee is an extraordinary study. If you would like to learn more about it, we heartily recommend the book, All About Coffee, by William Ukers. Written in 1928, it is as good a book on coffee as has been written and will delight you with detail.

Also the new book Short History of Coffee, by Kerr Gordon is delightful.

- Elliot R.H.The Experiences Of A Planter In The Jungles Of Mysore.

- Hakala Walter N. A Sultan in the Realm of Passion: Coffee in Eighteenth-Century Delhi. Eighteenth-Century Studies. 2014.

- http://www.teacoffeespiceofindia.com/coffee/coffee-origin

- https://bearessentialscoffee.co.uk/2020/05/29/coffee-tales-part-2-baba-budan-and-the-seven-seeds/

- https://blog.lovers.coffee/indian-coffee-indias-transition-from-tea-to-coffee/

- https://chikmagalurtourism.org.in/baba-budangiri-datta-peeta-chikmagalur

- https://digitalgems.nus.edu.sg/shared/colls/hisher/files/VoyMan.pdf

- https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/how-can-filter-coffee-be-so-different-yet-good/articleshow/22762503.cms?from=mdr

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baba_Budan

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baba_Budangiri

- https://food52.com/blog/25751-what-is-south-indian-filter-coffee

- https://isabelwrites.files.wordpress.com/2012/02/south-india-coffee-trail-in-silkwinds-oct-2015.pdf

- https://mediaindia.eu/freestyle/coffees-humble-roots-in-india/

- https://tattvamasiorganica.com

- https://theprint.in/india/datta-peetha-bababudangiri-how-karnatakas-hindu-muslim-shrine-became-ayodhya-of-the-south/786719/

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/symphony-of-tastes/poetic-rendition-of-indian-coffee-house-alleppey-india-in-sonnet-style/

- https://web.archive.org/web/20160917181332/http://www.teacoffeespiceofindia.com/coffee/india-coffees-varieties

- https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1342

- https://worldcoffeeresearch.org/focus-countries/india

- https://www.cntraveller.in/story/when-indian-coffee-house-was-the-countrys-living-room

- https://www.coffees.gr/baba-budan-story/?sl=en&s_layout=13

- https://www.deccanherald.com/india/karnataka/chroniclers-coffee-bean-2104866

- https://www.deccanherald.com/india/karnataka/chroniclers-coffee-bean-2104866

- https://www.firstpost.com/art-and-culture/a-short-history-of-the-india-coffee-house-conversation-revolutionary-politics-and-a-different-way-to-do-business-9184321.html

- https://www.folger.edu/blogs/shakespeare-and-beyond/islamic-history-of-coffee/

- https://www.kaapi.com.au/indian-filter-coffee

- https://www.madrasmusings.com/vol-31-no-1/coffee-and-the-city/

- https://www.masalakorb.com/south-indian-filter-coffee-filter-kaapi/

- https://www.masalakorb.com/south-indian-filter-coffee-filter-kaapi/

- https://www.middleeasteye.net/discover/india-coffee-lost-culture-mughal-empire

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/360227425_ORIGIN_OF_COFFEE_IN_INDIA_A_MAJOR_INDUSTRY

- https://www.slowfood.com/the-story-of-coffee-in-india/

- https://www.thesouthindiancoffeehouse.com/gallery/

- Jonathan Morris. Coffee: A Global History. 2019.

- Lee Allen, Stewart. The Devil’s Cup: Coffee, the Driving Force in History, Soho. 1999.

- Mennell Stephen. All Manners of Food. Eating and Taste in England and France from the Middle Ages to the Present. 1995.

- Nagegowda Dr H.L. Bettadinda Battalige – Coffeeya kathe (Story of Coffee).

- Nirmala Lakshman, Degree Coffee by the Yard. 2013.

- R.K.Narayan’s. My Dateless Diary. 1960.

- Saasubilli Paradesi Naidu. Coffee Industry in India – A Historical Perspective. Journal

- Of Humanities And Social Science. 2018. https://iosrjournals.org/iosr-jhss/papers/Vol.%2023%20Issue8/Version-4/D2308042933.pdf

- Stephen Blake. Shahjhanabad: The Sovereign City in Mughal India, 1639–1739. 1991.

- Thakur Sankarshan. The Brothers Bihari Paperback. 2015.

- The Experiences Of A Planter In The Jungles Of Mysore

- The Voyages and Travels of J. Albert de Mandelslo. 1638. https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.531053/2015.531053.mandelslos-travels_djvu.txt

- Vermani Neha. Spilling the Beans: The Islamic History of Coffee. https://themuslimtimes.info/2023/05/31/spilling-the-beans-the-islamic-history-of-coffee/

- Wild Antony. Coffee: A Dark History. 2005.