The love story between coffee and Naples is the subject of various tales: some food historians claim that coffee reached South Italy and Naples in the 1600s, others even two centuries earlier. The Neapolitan coffee ritual has given life to several traditions: Caffè sospeso (suspended coffe) evoke a sense of solidarity and altruism; the practice of the ‘caffé in ginocchio’ or the “consuolo“, coffee is used as an offering to give condolences to a family in mourning.

In this Article

On how coffee reached Naples and South Italy

The University of Salerno

Some historians believe, that coffee in Naples was already present in 1450, when the Aragonese reigned in the Campanian city. Some scholars, in fact, argue that the drink had arrived clandestinely at the University of Medicine of Salerno two centuries before Pietro Della Valle’s trip to the Middle East.

Pietro Della Valle

A second school of thought traces the appearance of the Neapolitan black coffee to the year 1614, when Pietro Della Valle – Roman musicologist – decided to leave Rome to escape from a sentimental displeasure and to live in Naples. He remains only a short period in Napoli: Pietro Della Valle begins a journey to the Holy Land, where he will settle for 12 years. Here he made the acquaintance of a particular drink called “khave“: a very fragrant black broth, poured into small porcelain bowls and, continually emptied (and refilled) during the conversations that followed the meal.

Della Valle told his Neapolitan friend Mario Schipano about this delight by letter. And this is how coffee began to be talked about even in the narrow streets of Naples, one of the first cities in Europe to know of its existence. It is also said that, upon his return, he brought ‘the kahve’ (coffee) to Naples.

Maria Carolina of Habsburg – Bourbon

CC0

However, food historians agree on one point: before spreading among the people, coffee was initially widely consumed in the salons of Naples thanks to Maria Carolina of Habsburg, daughter of Maria Theresia, queen of the two Sicilies (Naples being part of it). In 1768 Maria Carolina married Ferdinand IV of Bourbon and was crowned Maria Carolina, Regina (queen) di Napoli e Sicilia.

She introduced coffee culture at court, although it was believed that the typical black color of the drink was “bad luck” and the Church even considered it the devil’s drink.

It is said that in 1771, a ball was organized in the Royal Palace of Caserta where the coffee was served by those who were probably the first baristas, dressed in white jackets and hats: the first café (coffee house) of the Kingdom of Naples was born.

Along with the black drink, Maria Carolina also brought the Kipferl (the croissant) to the Neapolitan city: her successful coffee-croissant pairing was recommended to her by her sister Maria Antonietta of France.

At this time, coffee was already a part of high-society gatherings.

Coffee’s popularity rapidly spread throughout Naples. However, Naples was a major trade center in Europe and the East. Making it possible, that Arab traders already drunk coffee in South Italy.

Legend has it, that locals would sing about coffee, praising it as

the drink of hospitality, friendship and well wishes.

Transcribed is the legendary song praising coffee in the pamphlet authored by a gastronome named Pietro Corrado. (We could not find any confirmation of the song, or even that Pietro actually existed. On coffee illy s website he exists, but the mysterious Pietro Corrado eludes us…)

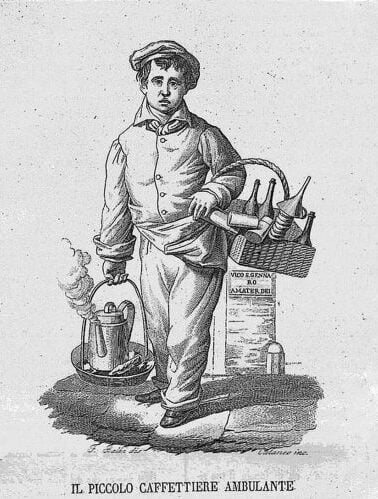

The tradition of Neapolitan Street coffee sellers

History and heritage shows, that Neapolitan coffee only became such with the appearance of the first street coffee sellers in the early 1800s. Families roasted their own beans on the street just outside their front doors over open fires ; sometimes they sold coffee as well.

From that moment, caffè began to spread throughout the city:

thanks to the coffee vendors, who traveled all over Naples with their containers full of coffee, milk, cups and sugar. At evening and nighttime he would shout:

‘O latte c’a t’aggio fatto roce roce! ‘o cafettièee…

te l’ho fatto questo caffè dolce dolce come il latte…

I made this sweet coffee for you as sweet, sweet as milk

Voci e gridi di venditori napoletani

At this time, coffee was generally brewed in a similar manner to Turkish coffee, in a pot or cezve – meaning very fine grounds would be brewed and consumed without a filter. The fine coffee powder would sit on the ground of the cup. Milk and sugar were added as in Voices and shouts of Neapolitan vendors,

Il caffettiéee… Lucia cammina!

Lucia is a female name, and on Lucia’s day the street coffee vendor would call

“coffee for Lucia, walk [over and drink one].”

Every day he changes the name: he would call the name of a saint, as marked on the christian calendar, so that we can consider him a true walking calendar. [The note is in Caravaglios, Voices and shouts of sellers in Naples, p. 57]

Caffé in ginocchio – coffee on the knees

There are two possible origins of the name “caffé in ginocchio” : the height of the coffee seller’s cart, which reached knee-high. Or the way to drink that coffee: crouched on the ground, using your knees as a support for the cup.

The practice of the ‘caffé in ginocchio’, spread between 1800 and 1900 in Italian cities, a street vendor, driving his own cart, would sell coffee to passers-by. The street seller re roasted and re boiled used grounds in order to sell the coffee at a reduced price to those who couldn’t afford to consume it at luxury coffee houses. A sort of recycling ahead of its time.

The drink would most probably be acidic, burnt, smelly, certainly over extracted and not exactly a first choice coffee.

The “caffé in ginocchio” cart was an ancestor of the kiosk. This is how Severino Pagani describes the cart, in his fascinating book on ancient Milanese crafts Il Barbapedanna and other figures and figurines of yesterday’s Milan:

“a small handcart… on which the large coffee pot was installed, and the coffee kept warm on a large charcoal brazier; on the same cart, the cups were piled all around the coffee pot… a candle stub, a small acetylene lamp, illuminated the modest scene, when the first customers of that strange, shaky, improvised shop arrived”.

The vendor arrived at dawn at his usual place (a tram station, the piazza in the city center…) and remained there until mid-morning when he moved away to make room for other carts selling ice cream, lemonade or carbonated water, watermelon or coconut.

Don Cafè in Naples

Giuseppe Schisano, a young Neapolitan from the Spanish Quarters, managed to revive the art of the traditional street coffee sellers of Italy. Freshly prepared coffee, strictly brewed with the typical Neapolitan coffee maker, the “cuccuma”, is since available through the streets of the city on a mobile coffee cart.

His project is called “Don Cafè. Street art coffee” and consists of a cargo-bike, a bicycle with pedal assistance, on which a steel surface with a gas stove is mounted. In keeping with the local coffee-as-hospitality tradition, Schisano asks for donations only at his cart.

Some people give five or six euros, some people leave 20 cents, and they’re thanked in the same way,

Schisano says.

Cuccuma– coffee embodies hospitality, history and heritage. This notion of serving coffee as an act of care is still found in the city’s tradition of caffè sospeso, or suspended coffee, which allows customers to pay for an extra cup at certain bars or coffee houses, so someone who can’t afford to pay can still enjoy one. It also lives in the Neapolitan tradition of o’ cuonzolo, derived from the Italian consolare, to console, which consists of bringing foods to people who have suffered a loss.

Cafè – The grand coffee house

Some botteghe – shops, took on particular characteristics that made them shine due to their affinity with literary and political academies: the so-called “Cafè”.

The grand cafés were opulent and luxurious, with chandeliers, huge mirrors, comfortable tables and chairs, and formally dressed waiters. The cafés offered an island of gentile peace in the midst of the busy city, a place where businessmen could discuss finances and intellectuals could discuss philosophy and the state of the world while indulging in coffee and pastries. Of course, such establishments were by their nature frequented only by those who were well off. Who else had either the time or the money for coffee culture.

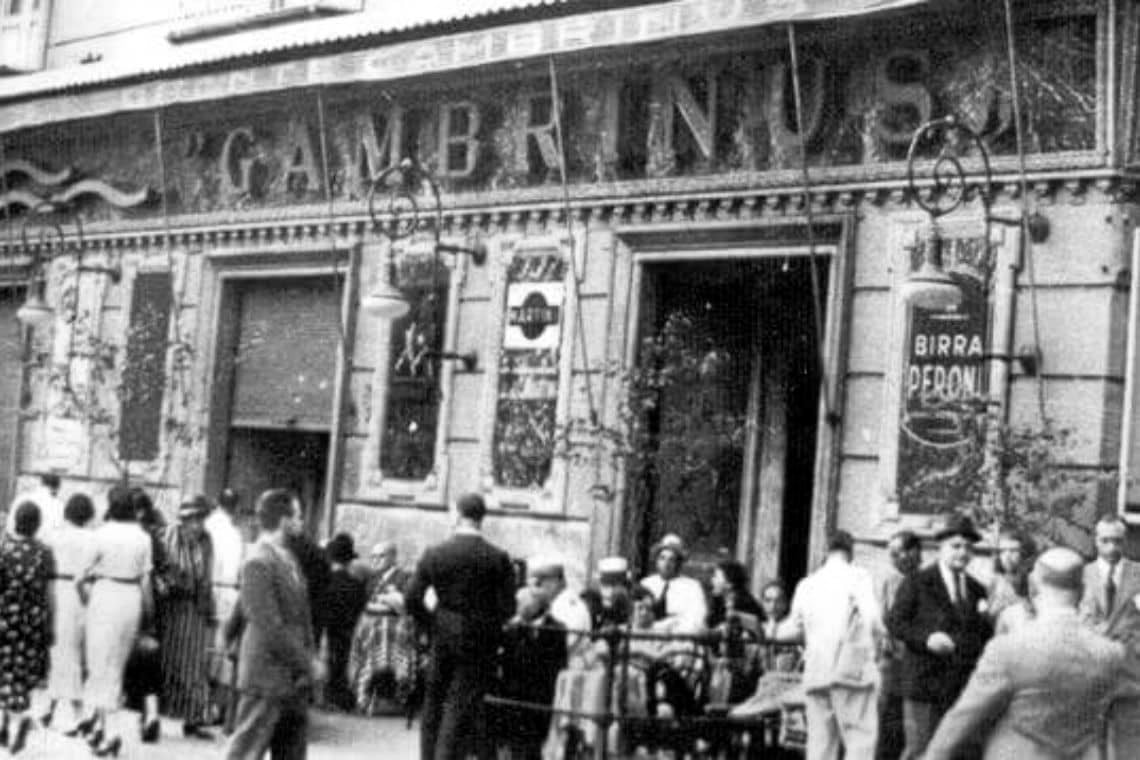

Cafè Gambrinus

Known as “Cafè of the seven doors” because of its many entrances, the first coffee house was founded in 1860. Today’s name is Gambrinus. It was known for being a meeting site for intellectuals and artists, including Gabriele D’Annunzio and Filippo Tommaso Marinetti.

It was also the meeting point of Oscar Wilde, Ernest Hemingway e Matilde Serao, the Princess Sissi and Jean Paul Sartre, Guy de Maupassant, Émile Zola and Benedetto Croce.

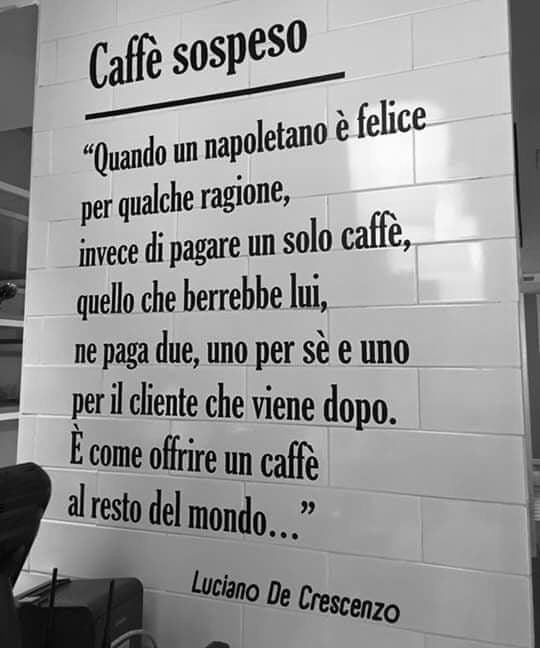

Il caffè sospeso or suspended coffee

The finely decorated literary cafè, Cafè Gambrinus, is the birth place of the concept of the caffè sospeso (suspended coffee or pending coffee), a kind gesture that involves paying for a coffee and leaving it for the less fortunate.

People can pay for an extra coffee and put the receipt in a bronze pot. Later, someone in need can come in and use the receipt to get a free coffee.

The tradition began in the working-class cafés of Naples, where someone who had experienced good luck would order a sospeso, paying the price of two coffees but receiving and consuming only one.

A stranger inquiring later whether there was a Sospeso or Caffè Suspiso available would then be served a coffee for free.

Another story places the origin of this tradition during the harsh times of the Second World War, as many people couldn’t afford food, drinks or milk, but they would return the favor as soon as they could.

Traditionally around Christmas or Easter, a sospeso coffee would also be gifted to someone anonymously.

The tradition of a free coffee paid forward, gave the title to a 2009 book by Neapolitan writer, director and actor Luciano De Crescenzo. Il caffe sospeso: Saggezza quotidiana in piccoli sorsi (Suspended coffee: Daily wisdom in small sips), which helped publicise the tradition throughout Italy. Daily wisdom in small sips was dedicated to what is not only a habit of the city of Vesuvius, but also a philosophy of life.

“When someone is happy in Naples, instead of paying a cup of coffee for himself, he just pays another one for someone else; it’s like offering a cup of coffee to the rest of the world.”

Luciano De Crescenzo

The tradition of the suspended coffee represents a simple, anonymous act of generosity towards humanity, and the kindness devolved to the people from a whole city. Nevertheless, this is not to be seen as an act of charity, but rather as the intention of sharing a pleasure.

The best part of coffee is sharing it, even if it’s with someone you don’t know.

Neapolitan saying

Naples is a city well known for its beauty, chaos and crime. Despite those, or perhaps because of them, its people are also famous for their solidarity in the face of hardship. Although this is not a tradition that all bars in Napoli comply with, nowadays this custom is making a comeback.

In 2010 a series of cultural events, readings, plays and festivals were held in Italy joining an initiative known as Rete del Caffè Sospeso. From 2011 the Giornata del Caffè Sospeso has been scheduled in conjunction with the Human Rights Day.

During the last years coffee shops in other countries started adopting the sospeso tradition, to increase sales, and to promote kindness and caring. In Bulgaria, Ukraine, Australia, Canada, Romania, Russia, Spain, Argentina, the United States, and Costa Rica you can find suspended coffee.

The heritage of coffee in Naples

One of the first words that pops into our minds when we talk about the south of Italy is probably “hospitality”. As soon as you step foot in Naples, you feel overwhelmed by the appetizing smells of freshly baked goods, coffee or by Neapolitan songs hummed aloud. As the brilliant writer, actor, and philosopher Luciano De Crescenzo once said:

“Wherever I went around the world, I saw that there was a need for a little of Naples.”

Coffee holds a special place in our collective Italian hearts, rather than just inviting my friends to hang out in their spare time, I would inquire: “shall we have a coffee?”… a practical excuse to get together.

To us having a coffee together is more than merely drinking coffee, it rather is a ritual, a moment you deserve, an excuse for gossip, and time to have a break with your beloved ones during the hustle and bustle of daily routine.

You know you will have your first one for breakfast, the second as a morning break, a third if you meet a friend, and the fourth must follow lunch. Only when you think it is over, someone will pop out asking: Shall we have a coffee? Un caffè?

In Naples and throughout the region of Campania – where the word “cuccuma” originates from – the Neapolitan espresso coffee pot is not just a brewing device, but a symbol of Naples’, possibly of South Italy’s’, distinct and unique coffee culture.

The preparation at home with this traditional coffee pot, is part of the daily ritual of drinking espresso, which, has become a symbol of Naples. Once used throughout Italy it was replaced by the Moka pot (patented by Alfonso Bialetti in 1933).

Different countries have developed various brewing methods:

- decoction methods (boiled coffee, Turkish coffee, percolator coffee and vacuum coffee),

- infusion methods (drip filter coffee, Indian filter Kapi and Napoletana), and

- the original Italian pressure methods (Moka and espresso)

As we embrace the aromas of an Italian coffee, we’re reminded that every demitasse, every bean, and every fragrance is a testament to the beauty of the sensory world we inhabit — a world enriched by the magic of flavors that have the power to awaken memories, and stir emotions.

Coffee is not just a product, it is something that unites Italy. It is tradition and heritage, it makes memories, perfume, makes us happy, nostalgic, and makes us remember family even if we are away from home.

O’ tazzulella – The coffee rituals of Neaple

The type of coffee and the pattern of consumption are associated with social habits and culture of the single regions of Italy. Variations in raw bean composition, in roasting conditions and in the extraction procedures used to prepare coffee brews result in a great diversity of O’ tazzulella (Neapolitan for tiny cup of coffee).

Strong, soft, hot: Neapolitan coffee is a symbol of the city together with Mt Vesuvius, the sun and pizza. Many Neapolitans say it’s the water from the Serino springs that gives the beverage more flavor, but that is only one story.

The ritual makes the difference. Comm’ cazz’ coce (drink while it is) damn hot – espresso is served very hot, piping hot, scorching, and baristas often recommend creating a mustache of coffee on the edge of the cup using a small spoon, to cool the high temperature porcelain demitasse.

What really characterizes the coffee taste are the Robusta coffee beans, which give body to the espresso, facilitating the formation of the much loved naturally forming crema. South Italians prefer robusta also because it has around twice the caffeine content of Arabica and more of the antioxidants responsible for many of the coffee’s health benefits.

The coffee in Napoli is STRONG and aromatic.

The body of the coffee is meant to be very thick if not syrupy with a pleasant aftertaste that is meant to last 15-30 minutes if properly extracted. Robusta drinkers look for the element of smokey, slightly bitter caramel, which is the natural coffee sugars being caramelized in the high temperature of a dark roast.

Neapolitan coffee is also stronger, because it is extracted with doses which are around 8 grams per cup (not the usually 7 grams). Therefore the espresso also presents a thick brown cream.

Having a coffee in an Neapolitan bar (in practice)

Italian coffee etiquette is very simple: good morning, please and thank you!

You pay for O’ tazzulella upfront and then present your receipt, the so called scontrino, to the bartender who will serve you in order of arrival.

There is usually no tipping in Italy, but only one situation in which Neapolitans consider it mandatory: at the bar counter! Here, and only here, it is necessary to deposit a small coin next to the coupon – it is an unwritten rule.

Neapolitans wouldn’t dare forget to tip the authoritative person who makes them their coffee

Amedeo Colella.

In most bars in Naples coffee is served dolce (sweet), sometimes even a sign “coffee is sweetened” welcomes customers. If you want your coffee amaro (bitter), without sugar, tell the barista. As we Italians are known to be very demanding when it comes to our coffee. Some of us would order a caffè in vetro – a coffee served in a glass rather than in a porcelain cup – or might ask for some cold milk in it. These are only two among the countless requests coffee lovers can have. Cappuccino is usually not drunk in South Italy at all.

Drinking an espresso or ristretto (20ml extraction) al bar is an act rigorously performed standing at the counter for a few quick minutes, moreover, drinking it while sitting on the inside generally increases the price of your shot.

Some bars will serve your coffee with a small glass of water. We drink this water before the coffee – as a palette cleanser to better enjoy the taste – rather than afterwards.

People from Campania love lever-piston machines and these are found in many bars.

From street coffee sellers to the Italian espresso machines in elegant coffee houses and neighborhood bars, coffee is sipped daily in Naples. It naturally sets the passing hours of the day and is both an intimate and a public ritual.

In Naples and Italy, coffee is much more than just a drink. It’s part of culture, a tradition known all over the world that inspires values of hospitality and sociability.

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

The history of coffee is an extraordinary study. If you would like to learn more about it, I heartily recommend the book, All About Coffee, by William Ukers. Written in 1928, it will delight you with detail.

- it.wikiquote.org (https://it.m.wikiquote.org/wiki/Voci_e_gridi_di_venditori_napoletani)

Voci e gridi di venditori napoletani - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caff%C3%A8_sospeso

- https://culinarybackstreets.com/cities-category/naples/2021/caffe-mexico-2/

- Allegra World Coffee Portal www.worldcoffeeportal.com

- Artusi Pellegrino. Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well, transl. Murtha Baca and Stephen Sartarelli. 2003.

- Biderman Bob. A people’s history of coffee and cafés. 2013.

- Café Culture Magazine www.cafeculturemagazine.co.uk

- Carosello Bialetti: la caffettiera diventa mito https://www.famigliacristiana.it/video/carosello-bialetti-moka-mito.aspx

- Cociancich Maurizio. Storia dell’ espresso nell’Italia e nel mondo. 100% Espresso Italiano. 2008.

- Coffee Connaisseur www.coffeeconnaisseur.com

- Coffee Geek www.coffeegeek.com

- Coffee Origins’ Encyclopedia www.supremo.be

- Coffee Research www.coffeeresearch.org

- Coffee Review www.coffeereview.com

- Coffee Sage www.coffeesage.com

- Coffeed.com www.coffeed.com

- Comunicaffe International www.comunicaffe.com

- Davids Kenneth. Espresso Ultimate Coffee. 2001.

- De Crescenzo Luciano. Caffè sospeso. Saggezza quotidiana in piccoli sorsi. 2010.

- De Crescenzo. Luciano. Il caffè sospeso.

- Eco Umberto. “La Cuccuma maledetta” in Agostino Narizzano, Caffè: Altre cose semplici. 1989.

- Global Coffee Report www.gcrmag.com

- Gusman Alessandro. Antropologia dell’olfatto. 2004.

- Hippolyte Taine, wrote in, Italy: Florence and Venice, trans J. Durand. 1869.

- https://www.italienaren.org/tradizioni-italiane-caffe-in-ginocchio/

- http://www.archiviograficaitaliana.com/project/322/illycaff

- http://www.baristo.university/userfiles/PDF/INEI-M60-ENG-Public-Regulation-EICH-v4-1.pdf

- http://www.coffeetasters.org/newsletter/en/index.php/category/a-baristas-life/

- http://www.coffeetasters.org/newsletter/it/index.php/il-galateo-del-caffe/01524/

- http://www.culturaacolori.it/fascismo-contro-le-parole-straniere/

- http://www.espressoitaliano.org/en/The-Certified-Italian-Espresso.html

- http://www.inei.coffee/en/Welcome.html

- https://archiviostorico.fondazionefiera.it/entita/585-bialetti-industrie

- https://bialettistory.com/

- https://cdn.intechopen.com/pdfs/55623.pdf Severini Carla. Derossi Antonio. Ricci Ilde. Fiore Anna Giuseppina. Caporizzi Rossella. How Much Caffeine in Coffee Cup? Effects of Processing Operations, Extraction Methods and Variables

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drip_coffee#Cafeti%C3%A8re_du_Belloy

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ISSpresso

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Italian_meal_structure

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neapolitan_flip_coffee_pot

- https://hal.science/hal-00618977/document

- https://hub.jhu.edu/magazine/2023/spring/jonathan-morris-coffee-expert/

- https://ineedcoffee.com/the-story-of-the-bialetti-moka-express/

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caff%C3%A8

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caff%C3%A8#Risvolti_etici_e_sociali

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napoletana

- https://italofonia.info/la-politica-linguistica-del-fascismo-e-la-guerra-ai-barbarismi/

- https://italysegreta.com/italian-hospitality-the-invite/

- https://library.ucdavis.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/LangPrize-2017-ElizabethChan-Project.pdf

- https://memoriediangelina.com/2009/08/11/italian-food-culture-a-primer/

- https://mostre.cab.unipd.it/marsili/en/130/the-everyday-eighteenth-century

- https://napoliparlando.altervista.org/cuccumella-la-caffettiera-napoletana/

- https://specialcoffeeitaly.com/barista-espresso-coffee-machine/

- https://specialcoffeeitaly.com/italian-breakfast-cappuccino-cornetto/?_gl=1*1gjfoya*_ga*OTE0MDM2ODM5LjE2OTMzNjE5OTg.*_ga_2HTE5ZB0JS*MTY5MzM2MTk5Ny4xLjEuMTY5MzM2Mjk0NS4wLjAuMA../

- https://specialcoffeeitaly.com/what-came-first-the-italian-bar-or-coffee/

- https://themokasound.com/

- https://uwyoextension.org/uwnutrition/newsletters/understanding-different-coffee-roasts/

- https://www.adir.unifi.it/rivista/1999/lenzi/cap2.htm

- https://www.bialetti.co.nz/blogs/making-great-coffee/using-bialetti-coffee-makers

- https://www.bialetti.com/ee_au/our-history?___store=ee_au&___from_store=ee_en

- https://www.bialetti.com/it_en/inspiration/post/ground-coffee-for-moka-should-never-be-pressed

- https://www.brepolsonline.net/doi/pdf/10.1484/J.FOOD.1.102222

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/Amsterdam/2014.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/Amsterdam/2014.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/Milan/2013/Gallery/Other/Amalia-Chieco

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/NewYork/2016.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/NewYork/2017.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/NewYork/2018.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/NewYork/2019.aspx

- https://www.coffeeresearch.org/science/aromamain.htm

- https://www.coffeereview.com/coffee-reference/from-crop-to-cup/serving/milk-and-sugar/

- https://www.comitcaf.it/

- https://www.ecf-coffee.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/European-Coffee-Report-2022-2023.pdf

- https://www.espressoitalianotradizionale.it/

- https://www.euronews.com/culture/2022/02/15/the-italian-espresso-makes-a-bid-for-unesco-immortality

- https://www.faema.com/int-en/product/E61/A1352IILI999A/e61-legend

- https://www.finestresullarte.info/en/works-and-artists/the-bialetti-moka-the-ultimate-romantic-design-object

- https://www.finestresullarte.info/opere-e-artisti/moka-bialetti-oggetto-design-ultimi-romantici

- https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/leisure/food/2022/02/15/italy-woos-unesco-with-magic-coffee-ritual/

- https://www.gaggia.com/legacy/

- https://www.gamberorossointernational.com/news/coffee-10-false-myths-to-dispel-on-the-beverage-most-loved-by-italians/

- https://www.gcrmag.com/calls-to-review-price-structure-of-italian-espresso/

- https://www.granaidellamemoria.it/index.php/it/archivi/caffe-espresso-italiano-tradizionale

- https://www.illy.com/en-us/coffee/coffee-preparation/how-to-make-moka-coffee

- https://www.illy.com/en-us/coffee/coffee-preparation/how-to-use-neapolitan-coffee-maker

- https://www.ilpost.it/2011/06/08/itabolario-bar-1897/

- https://www.itstuscany.com/en/bar-where-the-word-comes-from/“Cafe Hawelka”, John A. Irvin

- https://www.lastampa.it/verbano-cusio-ossola/2016/02/17/news/le-ceneri-di-renato-bialetti-nella-sua-moka-con-i-baffi-1.36565348/

- https://www.lavazza.com/en/coffee-secrets/neapolitan-coffee-maker

- https://www.lavazzausa.com/en/recipes-and-coffee-hacks/making-espresso-at-home

- https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/third-wave-coffee-meets-tradition-neapolitan-maker-bruno-lopez

- https://www.mumac.it/we-love-coffee-en/be-our-guest-en/progettazione-e-rito/?lang=en

- https://www.quartacaffe.com/images/pdf/carta-dei-valori.pdf

- https://www.repubblica.it/il-gusto/2021/07/26/news/caffe_il_piu_clamoroso_equivoco_gastronomico_d_italia-311835974/

- https://www.taccuinigastrosofici.it/ita/news/contemporanea/semiotica-alimentare/print/Pop-cibo-di-sostanza-e-circostanza.html

- https://www.thehistoryoflondon.co.uk/coffee-houses/

- https://www.wien.gv.at/english/culture-history/viennese-coffee-culture.html

- Illy Andrea. Viani Rinantonio. Furio Suggi Liverani. Espresso Coffee. The Science of Quality. 2005.

- International Coffee Organization www.ico.org

- Kerr Gordon. A Short History of Coffee. 2021.

- La cremina per il caffè: come farla bene. https://www.lacucinaitaliana.it/news/cucina/come-fare-la-cremina-del-caffe/

- Allen Lee Stewart. Devil’s Cup. A History of the World According to Coffee. 1999.

- Leonetto Cappiello – Wikipedia page on the creator of the 1922 poster La Victoria Aduino.

- Markman Ellis. The Coffee House. A Cultural History. 2005.

- Mennell Stephen. All Manners of Food. Eating and Taste in England and France. 1996.

- Montanari Massimo. Il riposo della polpetta e altre storie intorno al cibo. 2011.

- Montanari Massimo. Il sugo della storia. 2018.

- Morris Jonathan. A Short History of Espresso in Italy and the World. Storia dell’espresso nell’Italia e nel mondo. In M. Cociancich. 100% Espresso Italiano. 2008.

- Morris Jonathan. Coffee: A Global History. 2019.

- Morris Jonathan. Making Italian Espresso, Making Espresso Italian.

- National Coffee Association www.ncausa.org

- Pazzaglia Riccardo. Odore di Caffe’. 1999.

- Pendergrast Mark. Uncommon Grounds. The History of Coffee and How It Transformed Our World. 2019.

- Perfect Daily Grind www.perfectdailygrind.com

- Scaffidi Abbate Mario. I gloriosi Caffè storici d’Italia. Fra storia, politica, arte, letteratura, costume, patriottismo e libertà. 2014.

- Schnapp Jeffrey. The Romance of Caffeine and Aluminum. Critical Inquiry. 2001.

- Sibal Vatika. Food: Identity of culture and religion. 2018.

- Specialty Coffee Association www.sca.coffee

- Spieler Marlena. A Taste of Naples. 2018.

- Tea and Coffee Trade Journal www.teaandcoffee.net

- The Long History of the Espresso Machine. www.smithsonianmag.com

- The Pleasures and Pains of Coffee by Honore de Balzac

- The relaxation ritual https://themokasound.com/

- Tucker, Catherine M. Coffee Culture: Local Experiences, Global Commensality, Society and Cuture 2011.

- Virtual Coffee www.virtualcoffee.com

- World Coffee Research www.worldcoffeeresearch.org