It was at the beginning of the 18th century, with the spread of exotic drinks, like, coffee, tea, and chocolate, when refined tableware as we know it today was born. The cups were manufactured in Japan and China, frequently the same were intended for both coffee and tea.

Discover European Porcelain and the History and Evolution of the coffee and tea cup.

In this Article

Porcelain coffee – tea cups trough history and heritage

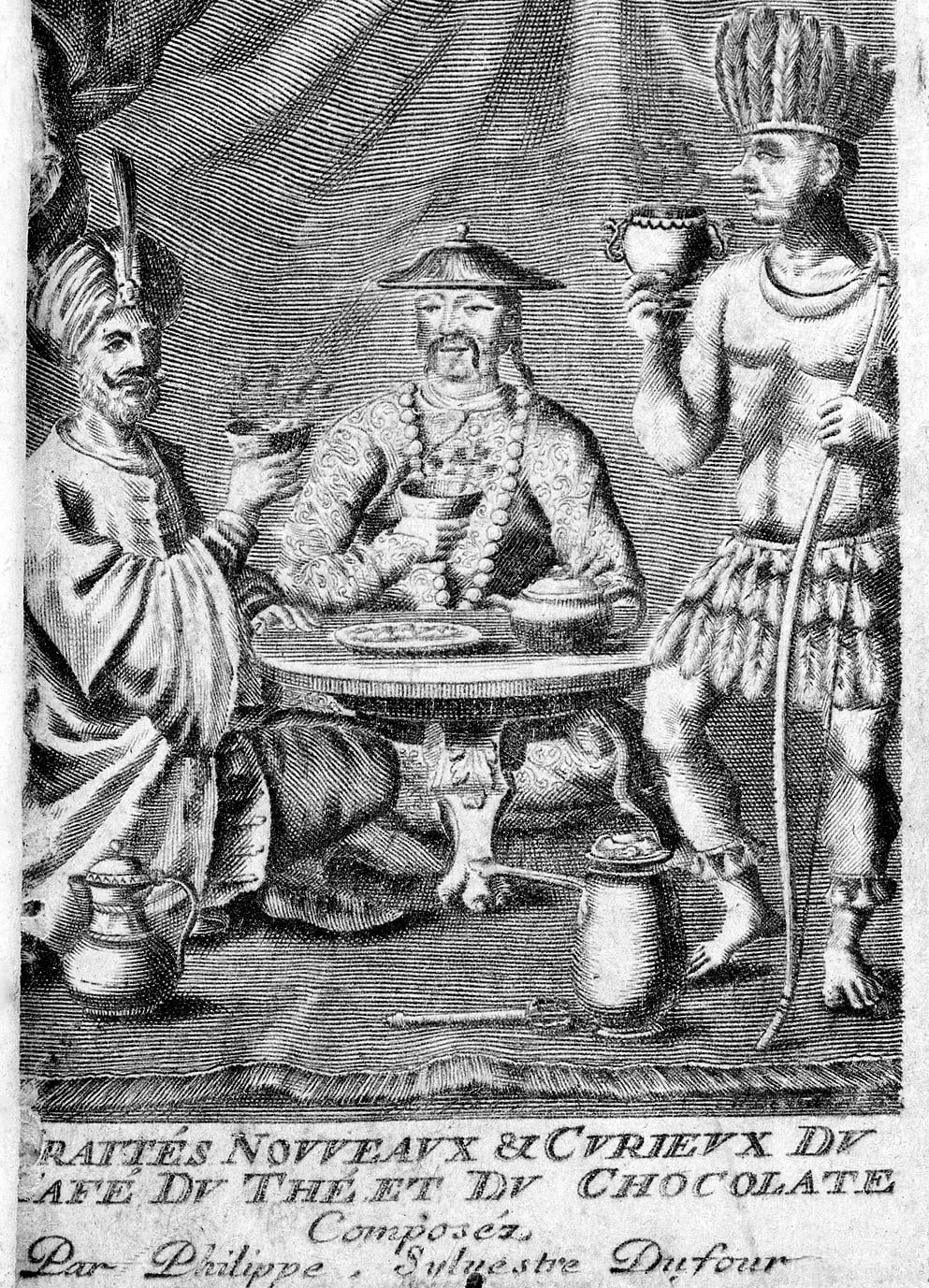

Philippe Sylvestre Dufour, Traitez nouveaux & curieux du café, du thé et du chocolate (New and Curious Treatise on Coffee, Tea, and Chocolate) shows how coffee from Arabia, tea from China, and chocolate from South America was served.

This French engraving, frontispiece for Dufour’s 1685 work, depicts a fanciful gathering of a Turk, a Chinese, and an Aztec inside a tent, each raising a bowl or goblet filled with the steaming beverage native to his homeland. On the floor to the left is the ibrik, or Turkish coffeepot, on the table at center the Chinese tea pot, and on the floor to the right the long-handled South American chocolate pot, together with the moline, or stirring rod, used to beat up the coveted froth. Baker, writing in 1891, commented that this image demonstrates “how intimate the association of these beverages was regarded to be even two centuries ago.”

The Arab-speaking parts of the Ottoman Empire, Egypt, Syria, Iraq and presumably the Arabian Peninsula,

were among the first to become familiar with coffee after its spread from Yemen in the fifteenth century, and they never switched to tea

Tea was the more popular of the two beverages in Iran, Turkey, and Morocco.

“Tazza” in archeology & art

Today’s cups are usually made of ceramic, porcelain or glass. In ancient times, they were made of bone, wood, stone, clay, terracotta, semi- and precious stones or metals, like lead, copper, silver and gold.

1911 Encyclopedia Britannica, states:

The word tazza,Ta-ZZ-ah, has been generally adopted by archaeologists and connoisseurs for this type of vessel, used either for drinking, serving small items of food, or just for display.

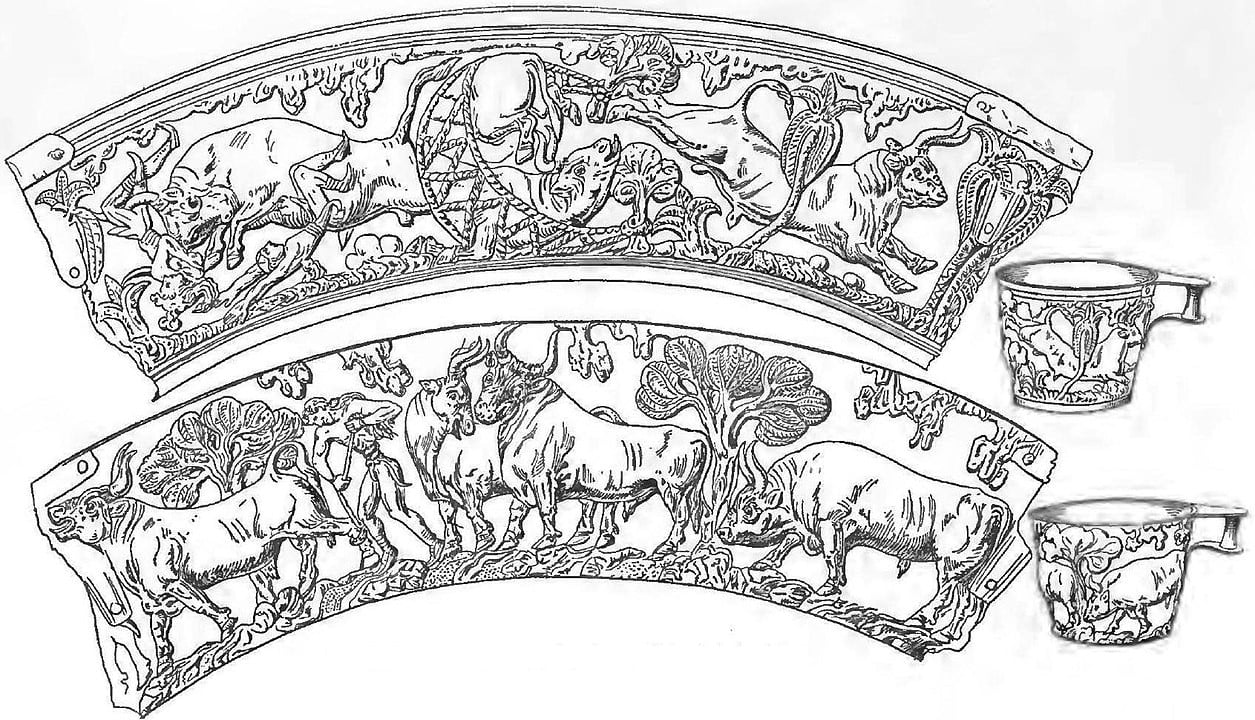

The Vaphio tazza

“Vapheio cup” is now used as a term for the shape of gold cups in Aegean archaeology.

Vaphio, is is an ancient site in Laconia (Greece), which houses a thòlos tomb, built for a Mycenaean king a series of jewels and treasures were also excavated.

By far the finest of the grave goods is a pair of golden cups decorated with scenes in relief. One cup shows the capture of bulls: A charging bull tosses a human with its horns, having knocked another down and escaped the net at right. The other the submission of these bulls, now tamed, the man tied a bull leg.

Tacce

Mid of the 15th century there is a decorated majolica fruit cup, gifted to Lorenzo the Magnificent. In some inventories it is called “tacce de frute”, as told in Pandolfini Auction House, Importanti Maioliche RinascimentaliImportant Italian Renaissance majolica.

In the Renaissance, however, ceramic cups and later rock crystal cups with animal-shaped handles began to be produced.

Venezian tazza

Gotheborg.com , describing shapes of the vessels of Chinese Pottery and Porcelain morphology writes about the tazza: Wide but shallow bowl on a stem with a foot; ceramic and metal tazzas were made in antiquity and the form was revived by Venetian glass makers in the 15th century. Also made of silver from the 16th century.

This Venezian tazza (Italian, “cup”, plural tazze) is a wide but shallow saucer-like dish either mounted on a stem and foot or on a foot alone.

Roman and Greek cups were used for water and wine.

Chinese porcelain

Together with silk and tea, ceramics were one of the three major goods supporting ancient China’s export trade

600 BC, porcelain was invented in China. Well suited to hot and cold drinks, porcelain cups are also relatively thin and lightweight. To test the color of the tea, white colored tea sets were more favorable. Til this day, fine bone china cups are, for some, a coffee lover’s favorite (and for us).

Chinese tea art was born in the Han Dynasty (206 BC-220 AD), matured in the Song Dynasty (960-1279) and flourished in the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368-1911).

In the Tang Dynasty (618-907), a wide range of ceramic products, including bowls, dishes, pots and vases, were transported across the world overland, and via the ancient Maritime Silk Road.

From the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) onward, the export of blue-and-white porcelain sparked a global fascination with these precious treasures from the East. Chinese porcelain makers began to produce pieces tailored to tastes in different countries after noticing a preference for kendis, a kind of water pot with a curved spout, in Southeast Asia, and began to produce for markets in places like Malaysia and Siam (Thailand).

Blue-and-white porcelain was itself influenced by the Islamic world’s taste. Several emperors in the 15th century are known to have supported Islam, and the Muslim (Ottoman and Persians) favoring of blue and white influenced the whole porcelain industry. The materials used to produce blue-and-white porcelain were imported from Persia during the early stage of its development.

From the 16th century, Kraak porcelain, a blue-and-white porcelain tailored for overseas markets only, was fired on a large scale in kilns in Fujian province. Though the word Kraak is Dutch, it is believed to derive from the Portuguese ships (carracks) that transported it. Kraak ware was made in the shape of deep bowls or wide dishes, whose surfaces were divided into segments and painted with motifs.

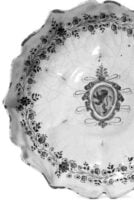

The 18th century saw increasing orders for blue-and-white armorial porcelain from the royal families and aristocrats of Europe. The porcelain usually bore the crests of the families painted at the center and were used on special occasions.

During the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), under the influence of the West, Chinese porcelain was being made in colors other than the green favored by the Song Dynasty (960-1279). Some makers used glass and enamel techniques introduced from Europe to produce the multicolored ceramics loved by the imperial family at the Forbidden City.

China has a 3,000-year history of ceramic making. Our porcelain has absorbed influences from other cultures to enhance itself over generations.

Wang Guangyao, porcelain expert from the Palace Museum China.

This vessel with a loop handle and thumb-rest to one side carved with foliate scrolls, and archaistic dragons and taotie masks, is set on a short foot.

Longquan celadon (龍泉青瓷) is a type of green-glazed Chinese ceramic, known in the West as celadon or greenware, produced from about 950 to 1550 ( Song to Ming Dynasty ). The jade-like glaze was popular in the Middle East due to its color, robustness and suitability for communal feasts. Jade was more valuable in ancient China than gold or silver, that is why this glaze was valuable.

Arabic glasses: Tàssah

‘Tazza‘ derives from the Arabic “tàssah“, a small glass used for hot drinks, which spread in the West during the Crusades.

Glass, colloquially, or a qadah قَدَح in classic Arabic, is an umbrella term for any type of drinking vessel. A finjan فنجان is either a small cylinder-shaped or tea cup-shaped vessel, available with or without a handle, that is used for drinking coffee. A kuub or koub كُوب is more of a typical tea cup or mug with a saucer.

Istikan is the most distinctive of the cup family. Solely used for drinking tea, an istikan is traditionally made from glass and designed to be thin-rimmed and wider at the top, before curving inwards and opening up at the base.

Glass in the Islamic World

Glass was made in ancient times, but its earliest origins are obscure. Egyptian glass beads are the earliest glass objects known, dating from about 2500 BC.

Other early glassworks are known in Alexandria during the Ptolemaic period and, later, in ancient Rome.

Glassblowing was probably developed during the 1st century BC by glass makers in Syria.

From about ad 700 to 1400 Islamic glass workers significantly refined engraving. As this 10th century glass cup, excavated at the site of Tepe Madrasa in Nishapur shows.

In addition to perpetuating the earlier modes of facet and boss cutting, they also introduced linear intaglio and relief cutting.

The ‘Golden Age’ of Islamic glassmaking was the late 12th to late 14th century. Persia and Mesopotamia (along with parts of Syria for some time) under the Seljuq Turks, and later the Mongols, and in the Eastern Mediterranean, the Ayyubid and Mamluk Dynasties are known for glassmaking. This Period is characterized by the perfection of various decorative traditions like marvering, enamelling, and gilding.

Later developments in the history of glass came during the 15th century in Venice. As early as the 13th century the Venetian island of Murano had become a center for glass making. Beginning in the first half of the 17th century, a new variety of glass began to be manufactured in Bohemia using a technique that revolutionized the glass making industry again.

In Italy espresso is still served in a glass. For coffee lovers it is a way to savor it with the eyes: with the glass you can see the color and foam better, which can distinguish a quality coffee from a coffee that is not.

Arabic cups

Al-Jaziri in writing about the distinctions between cups used for coffee and wine, states that porcelain was present in Jidda. In the Middle East, these small cups

intended for coffee consumption had no handles, until the nineteenth century when the European market began to produce cups with handles for export to the Middle East. Only a small amount of coffee was poured at a time, as it was customary to keep refilling the cups, and this also made the cups easier to handle, being filled with such a hot liquid.

The little drinking cups associated with consuming coffee are often referred to as fenjeyn, findjan, or finjan (meaning ‘small cup’)

Fenjan, finjan or fenjen فنجان

This picture portrays a traditional Arabic coffee pot (dallah), along with a cup of coffee with saffron and dried dates.

Arabic coffee is served plain or with sugar.

Arabic coffee is prepared in and served from a special coffee pot called dallah (Arabic: دلة); more commonly used is the coffee pot called cezve (also called rikwah or kanaka).

Cardamom is often added as flavouring, sometimes other spices like saffron (to give it a golden color), cloves, and cinnamon are used.

Arab coffee like in many cultures serves as a ceremonial act of kindness and hospitality.

Photo post-card by V. Derounian,1930, of an inhabitant of a Beehive village in Aleppo’s district in northern Syria.

He is sipping the traditional bitter [murra] Arabic coffee from a little porcelain cup and smoking a cigarette.

These porcelain cups were first imported to the Middle East from China in the 16th century. The cups imported from China had distinct Chinese styles and could hold 0.9 dl (3 OZ).

The Islamic potters were responsible for a number of important technical innovations, the most influential of which was the rediscovery of tin glaze in the 9th century BC. Though tin was first used by the Assyrians and according to some authorities was discovered as early as 1100 BC, it had fallen into disuse.

The ‘Abbāsid potters first used it in an attempt to imitate the texture of chinese T’ang wares, but soon it became the vehicle for characteristically Middle Eastern decoration. From Mesopotamia and Persia the technique was later taken to Moorish Spain and then to Italy and other parts of Europe, where it was employed for a number of important wares—Majolica, Faience, and Delft.

Kütahya began manufacturing coffee cups at the beginning of the 17th century, made evident through a 1608 royal edict (firman) in which the craftsmen are referred to as ‘cup makers’. Kütahya cups and saucers gained worldwide popularity during the 18th century, and displayed a variety of designs. Brosh describes these Ottoman ceramics:

…the cups were made from frit, a substance composed mainly of quartz with a small amount of white clay. The vessels were covered with a white slip, decorated with blue paint in a variety of patterns, mainly floral, and coated with a transparent lead glaze. They were widely distributed throughout the Islamic lands, where they were used both in private home and, apparently, coffeehouses.

Kütahya wares had a wide distribution, appearing in countries all across the Ottoman Empire,

“from at least as far afield as Jerusalem and Cairo in the East to Budapest (Buda) in the West, and Crimea in the North. A few even reached North America”

Hayes

Since then finjan cups are used to consume coffee trough many Mediterranean countries from Greece, Turkey to Morocco.

Finjan with zarth

At the time, the most sought-after cup was the fincan – from Arabic فِنْجَان (finjān) – without a handle, with the rounded bottom interlocking in an independent cup holder in the shape of a small egg cup.

It was called “zarth ظرف ” or ‘zarf zuruuf‘.

Türk Kahvesi

Türk Kahvesi, Turkish or Ottoman Coffee involves roasting the fresh beans over a fire, grinding them finely, and then boiling the ground beans slowly over charcoal embers in a small pot with a long handle called cezve. In Turkish coffee, the beans are ground even thinner than in Italian espresso, this makes it possible to serve the coffee with the grounds. The grounds settle in the tiny cup and do not enter the mouth.

Turkisch Coffee is flavored with cardamom, cinnamon, mastic, anise or clove. “Tartar” coffee comes with heavy cream, and “kervansaray” with carob (St John’s-bread, or locust bean).

In Ottoman times the drink was served thick, bitter, and near-boiling, with no sugar. Cardamom was the only spice added with any frequency, although in some disreputable quarters, opium and hashish apparently were also stirred in. The Ottoman coffeehouses used to enhance it with the aroma of exotic spices like saffron and even ambergris (dried whale vomit).

The foam of the Turkish coffee is so thick a camel can walk across it.

Turkish saying

The Ottomans used two types of coffee cups:

- The “no handle” Chinese porcelain coffee cups (also known as “Gawa” or “Mirra” in Arabic). They used to be the traditional Turkish coffee cups of the past. The cup was hold very carefully withstanding the scorching temperature of the cup while sipping the coffee.

- The Ottoman, filigree or jeweled metal holders with a porcelain or glass cup put into them

Then, Elif Ekin writes, they used porcelain cups with handles and two leading companies took the reigns for development and production: Kütahya and Güral Porselen. Kutahya took over for Iznik, the main producer of colorfully designed ceramics since the 15th century.

Standardizing the size of the turkish coffee cup (2-2.5 fl. oz. / 60-75 ml. of liquid) distinguishes it from the espresso cup. Between the small size and the thinner walls, the turkish coffee cup is designed to hold the hot temperature longer, inviting the sip and savor, as the coffee grounds settle. Todays kahve Fincan (with a handle) is still used for a cup of Turkish coffee.

The tasting cup

In 1600, with the wine, sometimes came a small silver footed Portuguese or Spanish “tasting cup” to be passed around the table, and known as a “bernegal –

“a cup for drinking with a wide mouth and undulating form”.

Rock crystal bernegals dated 1575-1660 are residing in the Prado, Madrid. They belonged to the Grand Dauphin Louis, son of Louis XIV of France, and father of king Philip V of Spain. Made in Milan – with related forms made possibly in Prague.

The puerperal cup

The puerperal cup, with two handles and lid appeared.

This was the model in use in Italy and France, while in America the puerperal cup had the shape of a jug with a spout (feeding cup).

In 1700, the use of precious metals was intended for the manufacture of luxury cups and bowls and therefore reserved for the wealthy; however, porcelain became, and still is, the favorite material for refined and artistic creations.

In the meantime, throughout Europe the consumption of tea, hot chocolate and coffee spread.

Italian bowls

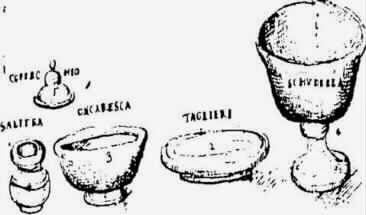

In the mid-16th century Cipriano Piccolpasso distinguished according to the dimensions:

“tazzoni o confettiere”, “cups or confectioners” (similar to large vases with lids to contain sweets);

“cups” and “bowls” all without handles. Piccolpassos treatise Li tre libri dell’arte del vasaio, Three books of the potter’s art, describes the art of ceramics. Published in print for the first time in Rome in 1857-58, it is an extraordinarily source on the history of artistic ceramics and techniques used in Italy during the Renaissance.

CC0

He also uses the words cups along with small bowls – plural – for tazzine e gli schudelini, when describing the production method.

There is no complete clarity on the difference between the various types, but it seems that most of these cups were not equipped with a handle. The dishware was often decorated and the patterns became finer and more ornate as pottery art developed.

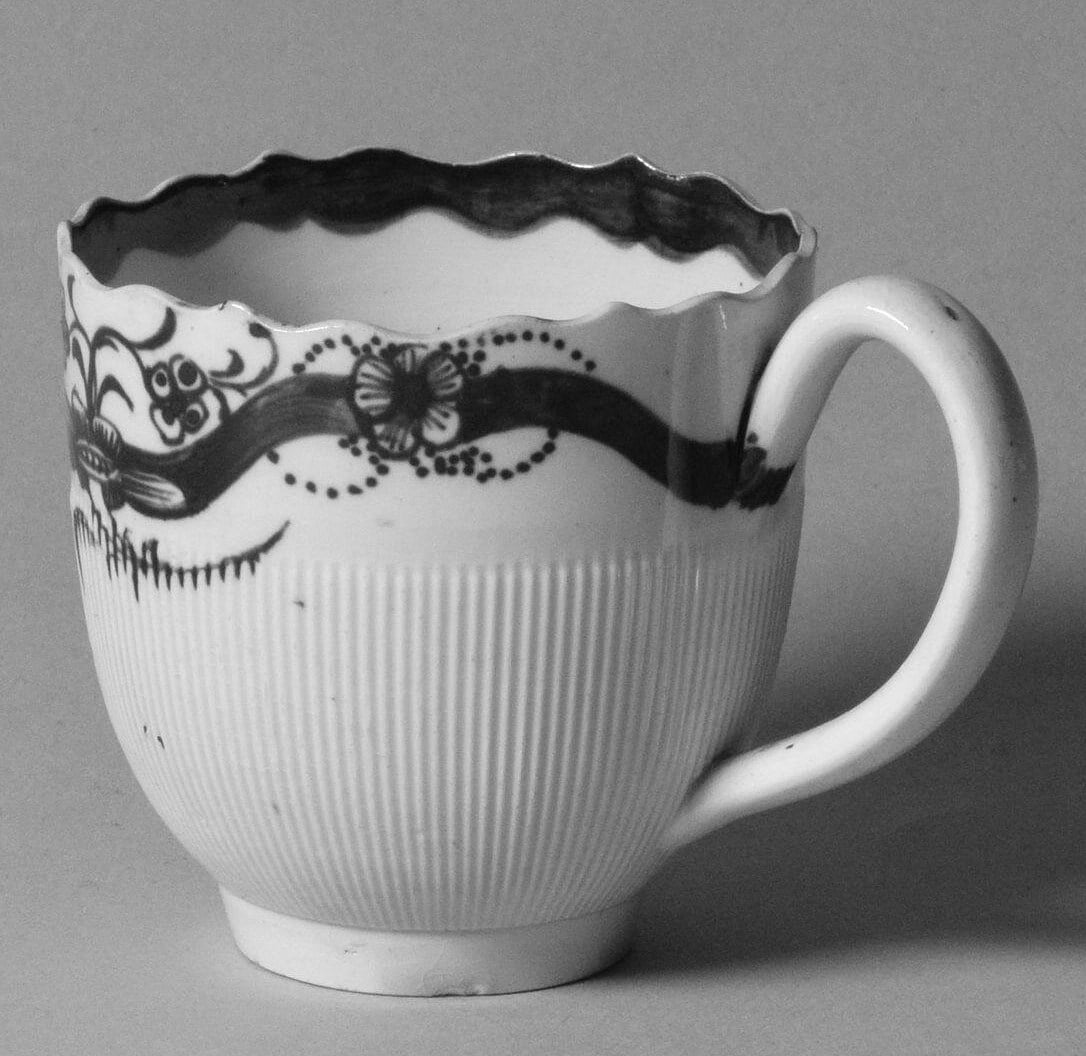

At the beginning of the 18th century, with the spread in the West of coffee, tea and chocolate the cup was born almost similar to how we know it today. Coffee was initially served in cups without a handle, in Arab style.

Around this time, Europeans began to imitate and produce fine Chinese porcelain, Fine Bone China.

Saucer – piattino

Nicolas de Blegny, Le Bon usage du the’ du caffe’ et du chocolat pour la preservation & pour la guerison des maladies, first printed in Paris, 1686. It shows fine finjan cups with saucers on a platau.

Legendary, the saucer was an idea born from the need of a girl who had difficulty serving hot tea, with a cup without a handle, to her father. She then went to a potter and asked him to create a plate.

In the 18th century, cups with handles and saucers took hold in Europe. Cups with a saucer with the same decoration appeared, which not only served as a support, but were also used to cool the coffee: the coffee was poured and drunk right from the saucer. In India it is still in use, when drinking filter Kapi.

As traditions change, drinking coffee from the saucer over time became bad manners, so much so that it was considered offensive.

Mazagran

There were several models of cups without a “handle – manico” in use: one of the most famous was a kind of tall glass in flute form, of thick ceramic called “mazagran ”, named after the Algerian city where in 1840 the French garrison was said to have sustained a memorable siege supported by liters of cold coffee mixed with alcohol.

The tall shape of the mazagran cup was inspired by traditional Algerian coffee drinking vessels. Mazagran cups are usually made of porcelain, terracotta, or glass, and are designed to have a “foot”. In some cases, mazagran cups may also have handles, but this isn’t common.

Historically, in France, mazagran coffee was served in “mazagrin” glasses, which closely resemble the traditional mazagran cup. In fact, the historic province of Berry in France – which is well known for its intricately-designed porcelain – is believed to have manufactured mazagran cups sometime in the 19th century.

Tea, coffee and chocolate sets

The history of the tea set begins in China during the Han dynasty (206–220 BC). At this time, tea ware was made of porcelain and consisted of two styles: a northern white porcelain and a southern light blue porcelain. These bowls were used for a variety of cooking needs and tea was mainly used as a medicinal elixir, not as a daily drink for pleasure.

The custom of the afternoon tea was defined in the Victorian era and concerned the entire English society, with different habits according to the financial possibilities of the people.

With the use of sweetening the coffee also sugar tongs and sugar bowls came into use and to stir the coffee, but never to put it into the mouth, the tea-, or coffee spoon.

The typical tea service in the 18th century consisted of:

cups, saucers and teaspoons presented on a tray with a tea,- coffee- and chocolate pot, milk or cream pot, sugar bowl and milk or cream jug.

The elements of coffee, tea and chocolate involved many props and pieces. The German Meissen Porcelain set, pictured below, depicts the typical elements found in sets and used for coffee, tea and chocolate around 1725.

Starting on the left-hand side and working around clockwise, the picture shows: slop bowl, a tea caddy, cocoa pot and cup with saucer, sugar bowl, coffeepot in the center, a tea pot and two round jugs with lid for milk and cream, two cups and matching saucers and plates in the center.

As the Meissen factory grew the artists began to turn not only to Chinese precedents but to introduce European motifs of decoration – landscape and harbour scenes derived from 17th century French and Dutch paintings, European flowers and hunting and genre scenes became more common. The shown service combines European scenes with a delicate turquoise-green ground which may have been intended to resemble Chinese celadon porcelain in its hue.

The beginning and rise of porcelain in Europe

Marco Polo first encountered porcelain at the court of the Mongolian emperor, Kublai Khan. He was mesmerized by the luminescence of the material — there was no written record of it anywhere in Europe at the time — comparing it to Mother of Pearl, like the shells found in the depths of Asian seas and used as money.

He wrote in Book of the Marvels of the World:

Gold is found here; but the small money is of porcelain, which circulates in all these provinces.[…]

The dishes are made of a crumbly earth or clay which is dug as though from a mine and stacked in huge mounds and then left for thirty or forty years exposed to wind, rain, and sun,

By this time the earth is so refined that dishes made of it are of an azure tint with a very brilliant sheen.

Marco Polo

As coffee, tea and chocolate spread to Europe, Chinese porcelain cups were gradually replaced by Western styles and products, reflecting the spread of coffee from the Ottoman Empire to Central and Western Europe.

Clara Borrelli states: The Dutch East India Company introduced European courts to porcelain in the 16th century, where chinoiserie became very much in vogue as a coveted addition to any cabinets de curiosité and a prized centerpieces to display on tables or furniture. Owning a piece of porcelain was a mark of social status before it became a business, when local craftsmen found out how it was made.

Production of Soft-Paste in Italy: Medici porcelain

Europeans tried to imitate Chinese porcelain. The first breakthrough in porcelain production came in Florence under Francesco de Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany. The low-fired porcelain became known as soft-paste porcelain or Medici porcelain and was produced from 1575 to 1587. Several other early experiments tried to imitate high-value Chinese hard-paste porcelain. Among them was the soft-paste frit porcelain, produced at the Rouen factory in France in 1673.

The first successful attempt to manufacture a commercially viable soft-paste porcelain was in the 1680s at Saint-Cloud, outside Paris. The Saint-Cloud factory typically produced blue-painted porcelain with a yellowish or ivory tone. In the late 17th century, the porcelain industry settled in French cities like Mennecy and Chantilly.

Production of Hard-Paste porcelain in Germany: Meissen Porzellan (Porcelain) Manufactory

Even though Europeans were manufacturing their own porcelain, the products were of poor quality compared to Chinese wares. However, Meissen porcelain began in 1708, when Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus developed his own method for making hard-paste porcelain in his castle workshop in Meissen, what is in today’s Germany. Hard-paste porcelain is typically blended from kaolin and petuntse to allow for a purer white finish after firing. Kaolin, also called china clay, is a silicate mineral that gives porcelain its plasticity, its structure; and petunse, or pottery stone, lends the ceramic its translucency and hardness.

The technique, which originated from Asia, made for an even better substrate for richly painted and gilded decorations. Its introduction in Europe changed the market for elegant ceramic services, and Meissen was primed to lead the charge.

Johann Friedrich Böttger, Tschirnhaus’ early collaborator and eventual successor, began producing their “white gold” hard-paste wares in 1710. By the following decade, the Meissen trademark was a renowned symbol of exceptional production.

When Böttger died in 1719, King Augustus II of Poland, who had been an early patron of the company, introduced a group of managing directors to inspire new designs and developments. This allowed Meissen to stay consistent in its remarkable quality of craftsmanship while changing its motifs for contemporary tastes.

The German Meissen porcelain manufactory faced intense competition from French soft-paste porcelain factories at Chantilly, Saint-Cloud, and Vincennes. The Vincennes factory soon got the status of Manufacture Royale, its customers being King Louis XV and Madame de Pompadour.

By the mid-1700s, the Vincennes premises were too cramped. Louis XV set up a new factory to create his own royal porcelain at Sèvres near the outskirts of Paris. By the late 1700s, Limoges produced countless porcelain blanks and shipped them to Sèvres for glazing.

The rise of Sèvres‘ neoclassical themes in the late 18th century led Meissen’s makers to respond with similar designs. A blend of quality and design fueled Meissen’s popularity throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. Although war efforts resulted in changes in management and production, the Meissen brand continued to be associated with high quality.

Production of British Creamware

Josiah Wedgwood (1730–95), is a British potter and tireless innovator. He developed a new coloured unglazed body called ‘jasper‘ and ‘pearlware‘. And perfected a cream-coloured earthenware known as ‘creamware‘, as a substitute for porcelain. Lightweight, yet durable, it proved ideal for moderately-priced domestic wares.

The ware Wedgwood produced was basically a creamware body, modified to make it whiter by the inclusion of china clay, which was then covered with a glaze containing some china stone. Most importantly a small quantity of cobalt was added to the glaze, which gave it a blueish tint. It is this cobalt blue glaze over a whitish body which is regarded as the most distinctive feature of pearl ware.

Often the glaze can appear quite blue in areas where it has been collected, such as around foot rings, or at the base of handles. Although technically ‘pearlware’ can be decorated in a number of ways the term is usually only used to refer to pieces decorated in underglaze blue.

Production of hard-paste porcelain in Italy: Manifattura di Doccia

The name Ginori 1735 refers to the eighteenth-century origins of the porcelain company, when the Marquis Carlo Andrea Ginori launches the future Manifattura di Doccia in Doccia, in the villa of the family estate.

Manifattura di Doccia invented the ‘stencil’ technique to decorate their porcelain items, compensating for its still scant painting skills. Carl Wendelin Anreiter von Zirnfeld, painter and chief decorator at the Du Paquier factory, came to Doccia from Austria in 1740 and marked the beginning of brush-painted decoration called ‘Pittoria’, which is still the hallmark of Ginori today.

At each workstation, masters of the craft bring ideas from the style department to life, which are developed through books, aesthetic research, and trial and error. But it’s the artisan that has the ultimate say in a project with logistical problems, adjusting as they go. What artisans know, they learned from those before them, and each idea is the result of manual testing and new manual abilities, Clara Borrelli knows.

Most of the things we make use of in our everyday lives ameliorate only the most minor of annoyances. The base rim of a coffee cup might have a small gap in it, for example, to ensure that any water that might pool after dish washing can leak away, just in case that tiny amount of water falls on you as you turn the cup over to put it back in the cupboard.

By the turn of the 19th century, European porcelain saw developments in both artistic and technical directions. Manufacturers began to experiment with new glazing techniques, colors mimicking hardstones, and complex forms. European porcelain cups have since gone through various trends and transformations.

Bar coffee cups

The twentieth-century espresso cup story is also an inevitable passage between craftsmanship and industrial standardization:

Working on materials and product design for food and drink means giving life to ideas that must necessarily combine beauty and functionality. In the case of espresso or cappuccino the cup is not just a design object but is used daily in bars and coffeehouses.

A professional coffee cup has to be made of hard, feldspathic porcelain, which is fired at a temperature of approximately 1400°C. This material is very resistant to wear; it is hygienic and retains its shiny appearance for a long time. It is also able to conduct and maintain heat to keep the coffee at the right temperature.

The Italian Espresso National Institute (INEI) recommends serving espresso in a white china cup holding 50−100 ml. This is the only cup whereby it is possible to fully appreciate the look of an excellent froth, the precious smell and the warm and smooth taste of espresso.

A soft, rounded interior allows the crema to land gently and retain its texture, heat, and visual appeal. Until 1990ies, in Italy, espresso cups were mostly available in plain white. At most, some featured a logo for decoration.

The characteristics of the perfect tazzina ta-ZZ-EE-naa, a tiny moka or espresso cup:

The shape must be a truncated cone to enhance the aroma of the coffee, rounded internally and with an egg-shaped base to guarantee compactness to the drink and good sealing of the crema.

The lower part of the cup must be thicker and the upper part thinner, because the temperature of the coffee must initially drop, but then must remain high during the sensory experience of tasting. The upper part is slimmer, moreover, to facilitate contact with the lips.

Illy’s Art Collection cups

Illy coffee was the first company to marry art and espresso. Architect and designer Matteo Thun re imagined the espresso cup in 1991. Since then, Illy’s Art Collection sets, which many credit with ushering in the collector’s cup era.

La tazzina da caffè The coffee cup is an iconic symbol of coffee culture and is never missing in Italian homes, bars and coffeehouses, this makes it something exceptional.

Artists, architects and designers of yesterday and today have committed themselves to designing the most varied coffee cups. Pouring a harmonious blend of the old and the new, tradition and innovation in a tiny cup of coffee.

Just holding a warm cup of coffee provides many with a sense of comfort – especially when cradling porcelain or glass. As we embrace the aromas of an Italian coffee, we’re reminded that every demitasse, every bean, and every fragrance is a testament to the beauty of the sensory world we inhabit.

A delicious caffè drunk from a shiny, light and elegant fine bone china cup is still unbeatable for us. Bone china is non-porous and thin-lipped for easier sipping.

Evviva la tazzina da caffè

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

The history of coffee is an extraordinary study. If you would like to learn more about it, I heartily recommend the book, All About Coffee, by William Ukers. Written in 1928, it will delight you with detail.

- Allegra World Coffee Portal www.worldcoffeeportal.com

- Allen Lee Stewart. Devil’s Cup. A History of the World According to Coffee. 1999.

- Artusi Pellegrino. Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well, transl. Murtha Baca and Stephen Sartarelli. 2003.

- Biderman Bob. A people’s history of coffee and cafés. 2013.

- Brosh, Na’ama. 2002 “Coffee Culture.” Catalogue for an exhibition of the same title, The Israel Museum: Jerusalem.

- Café Culture Magazine www.cafeculturemagazine.co.uk

- Carosello Bialetti: la caffettiera diventa mito https://www.famigliacristiana.it/video/carosello-bialetti-moka-mito.aspx

- Cociancich Maurizio. Storia dell’ espresso nell’Italia e nel mondo. 100% Espresso Italiano. 2008.

- Comunicaffe International www.comunicaffe.com

- Davids Kenneth. Espresso Ultimate Coffee. 2001.

- De Crescenzo Luciano. Caffè sospeso. Saggezza quotidiana in piccoli sorsi. 2010.

- De Crescenzo. Luciano. Il caffè sospeso.

- Eco Umberto. “La Cuccuma maledetta” in Agostino Narizzano, Caffè: Altre cose semplici. 1989.

- Global Coffee Report www.gcrmag.com

- Gusman Alessandro. Antropologia dell’olfatto. 2004.

- Hayes, J. W. 1992 Excavations at Saraçhane in Istanbul. Volume 2: The Pottery. Dumbarton Oaks,Washington, DC.

- Hippolyte Taine, wrote in, Italy: Florence and Venice, trans J. Durand. 1869.

- http://90905.homepagemodules.de/t155f59-Cappuccino-Kapuziner-Melange-oder-wie-jetzt.html

- https://web.archive.org/web/20210507033133/http://www.archivioceramica.com/CERAMISTI/T/Tazzini%20Luigi.htm

- https://web.archive.org/web/20240625190202/http://www.archivioceramica.com/FABBRICHE/R/Richard-Ginori.htm

- https://web.archive.org/web/20240625190202/http://www.archivioceramica.com/FABBRICHE/R/Richard-Ginori.htm

- http://www.archiviograficaitaliana.com/project/322/illycaff

- http://www.baristo.university/userfiles/PDF/INEI-M60-ENG-Public-Regulation-EICH-v4-1.pdf

- http://www.coffeetasters.org/newsletter/en/index.php/category/a-baristas-life/

- http://www.coffeetasters.org/newsletter/it/index.php/il-galateo-del-caffe/01524/

- http://www.culturaacolori.it/fascismo-contro-le-parole-straniere/

- http://www.espressoitaliano.org/en/The-Certified-Italian-Espresso.html

- http://www.inei.coffee/en/Welcome.html

- https://archiviostorico.fondazionefiera.it/entita/585-bialetti-industrie

- https://bialettistory.com/

- https://buongiornoceramica.it/eventi/archivio-della-ceramica-sestese/

- https://caffeaiello.cz/blog/curiosity/history-of-the-traditional-espresso-cup/

- https://cdn.intechopen.com/pdfs/55623.pdf Severini Carla. Derossi Antonio. Ricci Ilde. Fiore Anna Giuseppina. Caporizzi Rossella. How Much Caffeine in Coffee Cup? Effects of Processing Operations, Extraction Methods and Variables

- https://coffeelounge.delonghi.com/it/news/la-storia-della-tazzina/

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carlo_Ginori

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Teacup

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caff%C3%A8_sospeso

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coffee_cup

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drip_coffee#Cafeti%C3%A8re_du_Belloy

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ISSpresso

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Italian_meal_structure

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neapolitan_flip_coffee_pot

- https://etd.adm.unipi.it/t/etd-03182015-222130/

- https://filicorizecchini.us/blogs/news/the-curious-story-of-the-coffee-cup

- https://hal.science/hal-00618977/document

- https://hub.jhu.edu/magazine/2023/spring/jonathan-morris-coffee-expert/

- https://ineedcoffee.com/the-story-of-the-bialetti-moka-express/

- https://it.glosbe.com/it/mis_mil/tazzina%20da%20caff%C3%A8

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caff%C3%A8

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caff%C3%A8#Risvolti_etici_e_sociali

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napoletana

- https://italofonia.info/la-politica-linguistica-del-fascismo-e-la-guerra-ai-barbarismi/

- https://italysegreta.com/italian-hospitality-the-invite/

- https://lampoonmagazine.com/article/2022/04/30/ginori1735-porcelain/

- https://library.ucdavis.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/LangPrize-2017-ElizabethChan-Project.pdf

- https://localfoodeater.com/tag/luigi-tazzini/

- https://localfoodeater.com/tag/tazzini/

- https://materceramica.org/poi/archivio-della-ceramica-sestese/

- https://medium.com/@cosmiccoffeemarketplace124/the-history-of-coffee-mugs-from-ancient-times-to-modern-designs-fcefe9774fcf

- https://memoriediangelina.com/2009/08/11/italian-food-culture-a-primer/

- https://mostre.cab.unipd.it/marsili/en/130/the-everyday-eighteenth-century

- https://museoginori.org/magazine/gio-ponti-e-la-richard-ginori

- https://napoliparlando.altervista.org/cuccumella-la-caffettiera-napoletana/

- https://newsoggi.wordpress.com/2014/07/13/la-tazzina-del-caffe-12/

- https://northernwilds.com/history-in-a-cup-of-tea/

- https://prochet.blogspot.com/2015/01/quante-storie-per-una-tazzina.html?m=1#!

- https://raccoltestorichedibrera.altervista.org/category/pubblicazioni/?doing_wp_cron=1698766015.6337399482727050781250

- https://specialcoffeeitaly.com/barista-espresso-coffee-machine/

- https://specialcoffeeitaly.com/italian-breakfast-cappuccino-cornetto/?_gl=1*1gjfoya*_ga*OTE0MDM2ODM5LjE2OTMzNjE5OTg.*_ga_2HTE5ZB0JS*MTY5MzM2MTk5Ny4xLjEuMTY5MzM2Mjk0NS4wLjAuMA../

- https://specialcoffeeitaly.com/what-came-first-the-italian-bar-or-coffee/

- https://web.archive.org/web/20210120000749/https://tazzando.com/l-evoluzione-delle-tazze/

- https://themokasound.com/

- https://unamoreditazza.altervista.org/artisti-delle-tazze/

- https://uwyoextension.org/uwnutrition/newsletters/understanding-different-coffee-roasts/

- https://www.academia.edu/38111827/Gio_Ponti_and_Richard_Ginori

- https://www.adir.unifi.it/rivista/1999/lenzi/cap2.htm

- https://www.antiquanuovaserie.it/fiori-e-decori-in-quel-di-meissen/

- https://www.bialetti.co.nz/blogs/making-great-coffee/using-bialetti-coffee-makers

- https://www.bialetti.com/ee_au/our-history?___store=ee_au&___from_store=ee_en

- https://www.bialetti.com/it_en/inspiration/post/ground-coffee-for-moka-should-never-be-pressedhttps://www.brepolsonline.net/doi/pdf/10.1484/J.FOOD.1.102222

- https://www.britannica.com/art/pottery/Early-Islamic

- https://www.britannica.com/technology/glass

- https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/culture/2015-12/23/content_22785220.htm

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/Amsterdam/2014.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/Milan/2013/Gallery/Other/Amalia-Chieco

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/NewYork/2016.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/NewYork/2017.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/NewYork/2018.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/NewYork/2019.aspx

- https://www.coffeeresearch.org/science/aromamain.htm

- https://www.coffeereview.com/coffee-reference/from-crop-to-cup/serving/milk-and-sugar/

- https://www.comitcaf.it/

- https://www.comunicaffe.it/luigi-tazzini/

- https://www.comunicaffe.it/tazza-luigi-tazzini/

- https://www.comunicaffe.it/tazzina-del-caffe-storia/

- https://www.ecf-coffee.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/European-Coffee-Report-2022-2023.pdf

- https://www.espressoitalianotradizionale.it/

- https://www.euronews.com/culture/2022/02/15/the-italian-espresso-makes-a-bid-for-unesco-immortality

- https://www.faema.com/int-en/product/E61/A1352IILI999A/e61-legend

- https://www.finestresullarte.info/en/works-and-artists/the-bialetti-moka-the-ultimate-romantic-design-object

- https://www.finestresullarte.info/opere-e-artisti/moka-bialetti-oggetto-design-ultimi-romantici

- https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/leisure/food/2022/02/15/italy-woos-unesco-with-magic-coffee-ritual/

- https://www.gaggia.com/legacy/

- https://www.gamberorossointernational.com/news/coffee-10-false-myths-to-dispel-on-the-beverage-most-loved-by-italians/

- https://www.gcrmag.com/calls-to-review-price-structure-of-italian-espresso/

- https://www.ginori1735.com/us/en

- https://www.ginori1735.com/us/en/history

- https://www.giornaledelcaffe.it/category/curiosita/

- https://www.giornaledelcaffe.it/storia/la-curiosa-storia-della-tazzina-di-caffe/

- https://www.giornaledelcaffe.it/storia/storia-del-cucchiaino-da-caffe-da-uno-strumento-di-nicchia-ad-un-arnese-universale/

- https://www.granaidellamemoria.it/index.php/it/archivi/caffe-espresso-italiano-tradizionale

- https://www.illy.com/en-us/coffee/coffee-preparation/how-to-make-moka-coffee

- https://www.illy.com/en-us/coffee/coffee-preparation/how-to-use-neapolitan-coffee-maker

- https://www.ilpost.it/2011/06/08/itabolario-bar-1897/

- https://www.invaluable.com/blog/limoges-china/

- https://www.invaluable.com/blog/wedgwood-china/

- https://www.italienaren.org/tradizioni-italiane-caffe-in-ginocchio/

- https://www.itstuscany.com/en/bar-where-the-word-comes-from/“Cafe Hawelka”, John A. Irvin

- https://www.kobo.com/hk/en/ebook/object-studies

- https://www.lacucinaitaliana.it/article/perche-il-caffe-si-serve-nella-tazzina-consigli-galateo-esperto/

- https://www.lastampa.it/verbano-cusio-ossola/2016/02/17/news/le-ceneri-di-renato-bialetti-nella-sua-moka-con-i-baffi-1.36565348/

- https://www.lavazza.com/en/coffee-secrets/neapolitan-coffee-maker

- https://www.lavazzausa.com/en/recipes-and-coffee-hacks/making-espresso-at-home

- https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/third-wave-coffee-meets-tradition-neapolitan-maker-bruno-lopez

- https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/opere-arte/schede/XC080-00271/

- https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/ricerca/?current=4&q=tazzina+caff%E9&a=202#

- https://www.mumac.it/we-love-coffee-en/be-our-guest-en/progettazione-e-rito/?lang=en

- https://www.politesi.polimi.it/handle/10589/140780

- https://www.pressrepublican.com/news/lifestyles/tea-cups-steeped-in-rich-history/article_d35b8d14-d3bb-5898-8972-0267b47afadb.html

- https://www.quartacaffe.com/images/pdf/carta-dei-valori.pdf

- https://www.repubblica.it/il-gusto/2021/07/26/news/caffe_il_piu_clamoroso_equivoco_gastronomico_d_italia-311835974/

- https://www.taccuinigastrosofici.it/ita/news/contemporanea/semiotica-alimentare/print/Pop-cibo-di-sostanza-e-circostanza.html

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00076791.2020.1801643

- https://www.thehistoryoflondon.co.uk/coffee-houses/

- https://www.wholelattelove.com/blogs/articles/history-of-the-coffee-mug

- https://www.wien.gv.at/english/culture-history/viennese-coffee-culture.html

- Illy Andrea. Viani Rinantonio. Furio Suggi Liverani. Espresso Coffee. The Science of Quality. 2005.

- International Coffee Organization www.ico.org

- it.wikiquote.org (https://it.m.wikiquote.org/wiki/Voci_e_gridi_di_venditori_napoletani)

Voci e gridi di venditori napoletani - Kerr Gordon. A Short History of Coffee. 2021.

- La cremina per il caffè: come farla bene. https://www.lacucinaitaliana.it/news/cucina/come-fare-la-cremina-del-caffe/

- Leonetto Cappiello – Wikipedia page on the creator of the 1922 poster La Victoria Aduino.

- Markman Ellis. The Coffee House. A Cultural History. 2005.

- Mennell Stephen. All Manners of Food. Eating and Taste in England and France. 1996.

- Montanari Massimo. Il riposo della polpetta e altre storie intorno al cibo. 2011.

- Montanari Massimo. Il sugo della storia. 2018.

- Morris Jonathan. A Short History of Espresso in Italy and the World. Storia dell’espresso nell’Italia e nel mondo. In M. Cociancich. 100% Espresso Italiano. 2008.

- Morris Jonathan. Coffee: A Global History. 2019.

- Morris Jonathan. Making Italian Espresso, Making Espresso Italian.

- National Coffee Association www.ncausa.org

- Pazzaglia Riccardo. Odore di Caffe’. 1999.

- Pendergrast Mark. Uncommon Grounds. The History of Coffee and How It Transformed Our World. 2019.

- Scaffidi Abbate Mario. I gloriosi Caffè storici d’Italia. Fra storia, politica, arte, letteratura, costume, patriottismo e libertà. 2014.

- Schnapp Jeffrey. The Romance of Caffeine and Aluminum. Critical Inquiry. 2001.

- Sibal Vatika. Food: Identity of culture and religion. 2018.

- Specialty Coffee Association www.sca.coffee

- Spieler Marlena. A Taste of Naples. 2018.

- Tea and Coffee Trade Journal www.teaandcoffee.net

- The Long History of the Espresso Machine. www.smithsonianmag.com

- The Pleasures and Pains of Coffee by Honore de Balzac

- The relaxation ritual https://themokasound.com/

- Tucker, Catherine M. Coffee Culture: Local Experiences, Global Commensality, Society and Cuture 2011.

- World Coffee Research www.worldcoffeeresearch.org