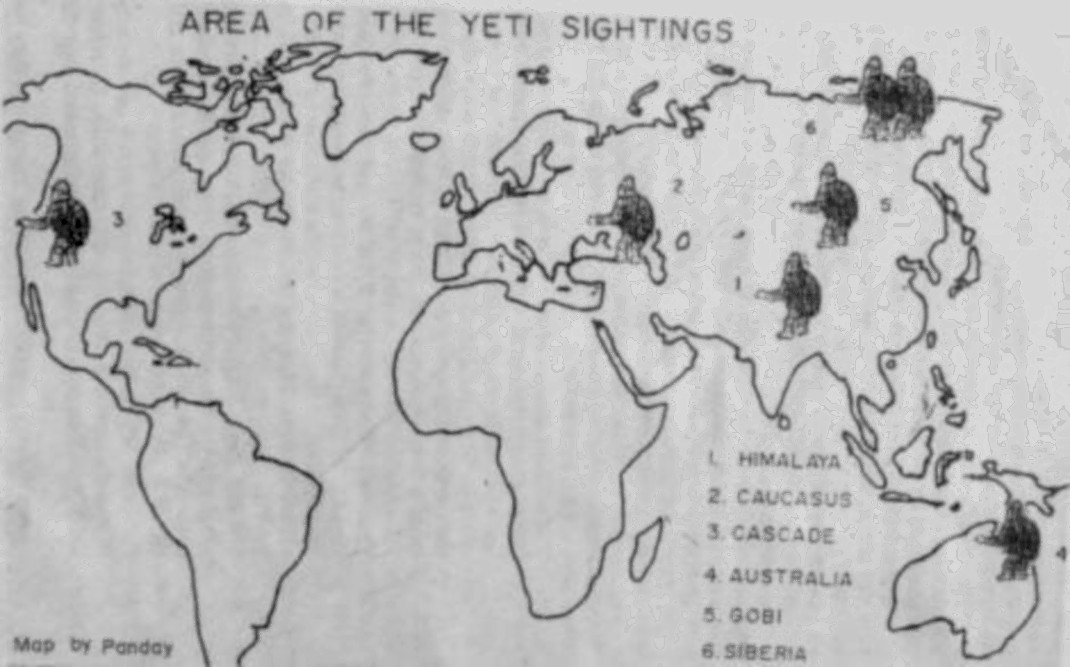

Across the Himalayas the yeti is known by many names and was seen as real, familiar for generations in a half-dozen countries from Tibet to Pakistan. A region flush with wildlife, where tigers, bears and wild dogs roamed thick mountain forests, icy mountaintops and remote river valleys.

Here, if nowhere else, the yeti was simply one more creature. Discover Myth and Folklore of the Yeti in the Himalayas.

In this Article

Wild woman and wild man

Wild, uncontrollable landscapes have always inspired fear in the lonely traveler, pilgrim, or hunter: mountain passes, deep forests, and jungles were in fact seen as dangerous places, where wild, non-human creatures, ghosts, spirits, and deities were roaming, lurking, and stalking their prey.

Ideas and beliefs about wild, hominoid beings inhabiting untamed landscapes are in no way exclusive to the Himalayas:

from ancient Near Eastern sources to European folklore, from the Iranic plateau to the Russian and Mongolian steppe and then down to the Chinese forests, African jungles and American landscapes, we have innumerable accounts of sightings, rumors, legends, and folktales focusing on the “wild woman or wild man.”

Yeren: Chinas’ wild man

In ancient Chinese literature there are several mentions of hairy humanlike beings, and eyewitness reports have persisted into the modern era. Oliver D. Smith, writes in his paper, The Wildman of China: The Search for the Yeren, 2021:

The wildman has long been reported as dwelling in the forests and mountains of Shennongjia (northwestern Hubei), where it is called a yeren (also spelled yeran 野人, lit., “wildman”). Sightings of the yeren in these forests date back to the sixteenth century: Fangxianzhi, a local gazette of Fangxian, first mentioned the yeren in 1555.

During the Qing dynasty (1644–1912), Fangxianzhi published an article that said a group of yeren inhabited caves in the mountains of Fangxian (about 90 km north of

Shennongjia); these mysterious wild men were said to have eaten domestic chickens and dogs.

Dozens of alleged sightings of the Chinese wildman in the forests of Shennongjia eventually prompted a large-scale expedition of scientists to investigate the region in 1977. Three possible explanations for the Chinese Wildman emerged:

Unknown species hypothesis – elusive animals,

like an unknown orangutan species or a relict Gigantopithecus.

Known species hypothesis – misidentified animals,

like the yeren, feifei, xingxing, and maoren, are more resembling a human, rather than like any other species. In Chinese artwork in the early seventeenth century, xingxing look humanlike, while maoren are described as human in their behavior.

Li Yanshou’s description of maoren in Nan Shi reads, “hairy men clambered over a city wall, while crying out and hurling stones.”

The poet Yuan Mei in his Xin Qi Xie (published in 1781) described maoren as “monkeylike,” but not actual monkeys, presumably because of their human characteristics.

Yi Zhou Shu (fourth century BCE) and a Chinese dictionary, Erya (third century BCE), take note of a manlike hairy creature named feifei (狒狒, usually translated as “baboon”). The latter says, “feifei resembles man; it has long hair hanging down its back, runs quickly and devours people.”

Feifei is also described as resembling humans despite oddities such as long lips and the absence of knees. Duan Chengshi in his Youyang Zazu (a miscellany on legends, 853 C.E.), describes the feifei as follows:

If you drink the blood of the feifei, you will be able to see ghosts. It is so strong that it

can shoulder one thousand catties … its upper lip always covers its head. Its shape is like

that of an ape. It uses human speech, but it sounds like a bird. It can foretell life and

death. Its blood can dye things dark purple, and its hair can be used to make wigs.

Legend has it that its heels face backwards … hunters say that it has no knees.

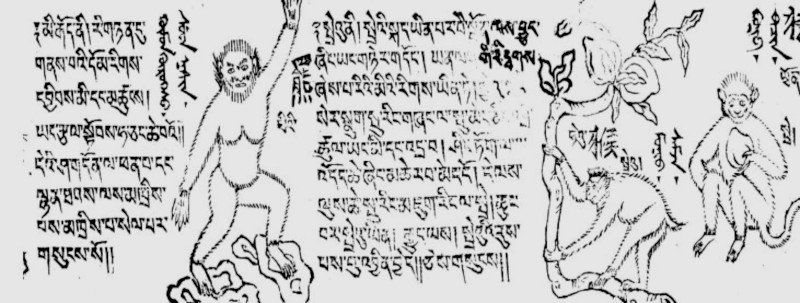

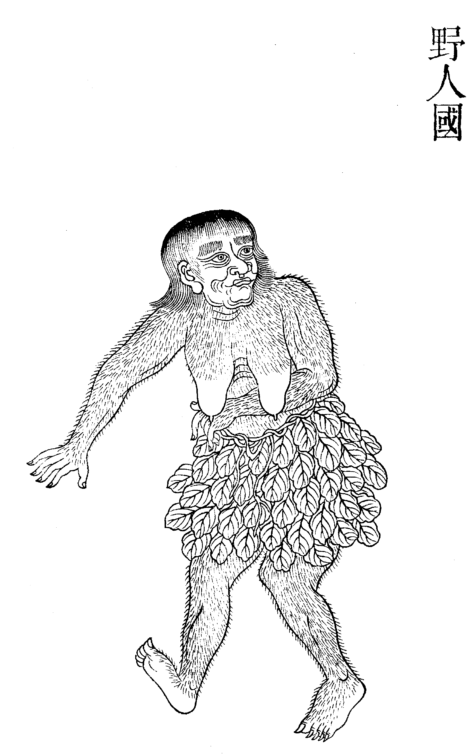

A drawing of the legendary creature shēngshēng (狌狌

), also written xīngxīng (猩々) from a 1596 edition of The Classic of Mountains and Seas (山海經 , Shān Hāi Jīng). Hu Wenhuan 胡文焕 (fl. 1596–1650) ed. Public domain, edited.

Another type of wildman mentioned in Erya is xingxing (猩猩, usually translated as “orangutan”). A second-century C.E. annotated edition of Huainanzi (139 BCE) by Gao Yu describes xingxing as having a human face but the “body of a beast.”

The xingxing is, sometimes, shown in artwork as carrying a sword.

The maomin in the Shan Hai Jing are called hairy people and are undoubtedly human. The tendency of modern Chinese scholars to identify xingxing with the orangutan and feifei with the baboon are therefore questionable identifications.

Hairy European hypothesis – bearded men

Stories about the wildman probably originated in early encounters of the Chinese with bearded European peoples. In fact traditions regarding the wildman in China can be traced back to the Qin dynasty when Chinese first encountered Greeks in the Far East and, unfamiliar with their hairier physical appearance (lighter-colored hair and heavier beards), originated stories about a semi-human being.

ETYMOLOGY

The term “yeti” itself is a merger of the Sherpa words “yah” (rock or cliff) and “teh” (animal).

However, some researchers have also deduced that the term comes from the Sanskrit “yaksha”, a hairy being with superhuman strength.

Himalayan peoples do refer to the yeti or similar mysterious and rarely seen creatures or indigenous wildlife by a number of names:

Mongolia

The Mongolians call it

- Almas

- Baman is the name given by the Udshur people of the Hindu Kush

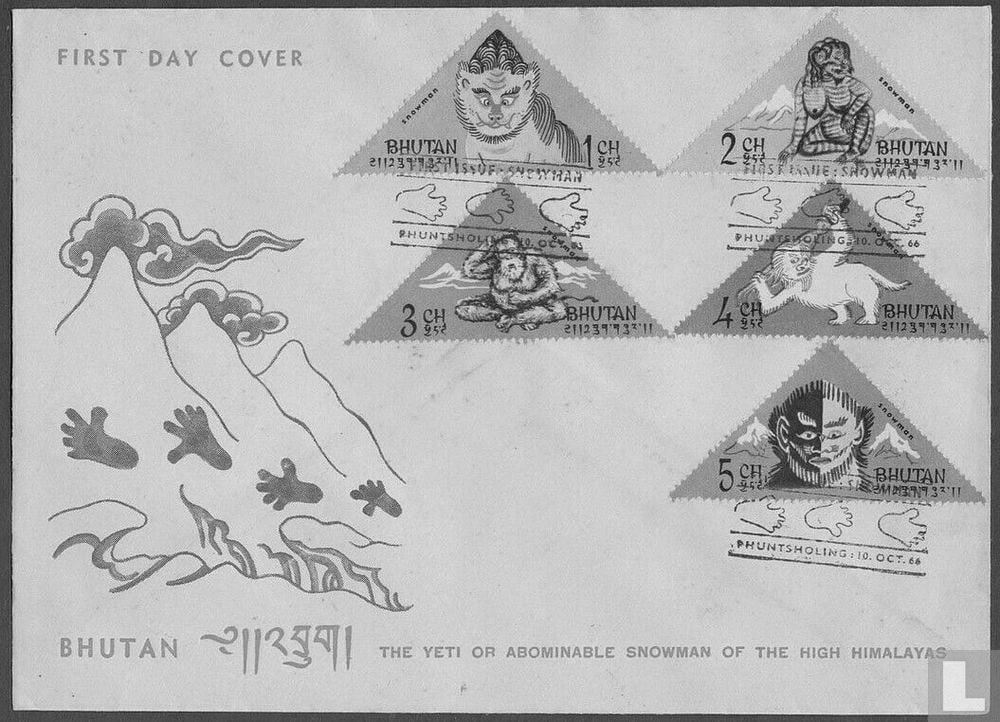

Bhutan

In Bhutan, where they even have stamps commemorating the creature, the yeti is known as

- Mighu or

- Migoi (strong man).

India

In India, the Sikkimese call it Megur or latsen (spirits of mountain passes)

The people of Tripura, a North East Indian state, believe in “Bura Debota” (old man – evil spirit) which has uncanny similarities to the yeti.

Lepcha people, who live in Bhutan, India, Tibet and Nepal know the Yeti as:

- Chu Mung (Glacier Spirit)

- Jhampey Mung (lord of the animals)

Tibet

The Tibetans have a number of titles

- Chemo,

- Dremo (a human that transformed into a wildman),

- Chu-mung (spirit of the glaciers), and

- Mig-de or Michê (bear man).

- Dzu-teh (cattle bear) referring to the Himalayan brown bear.

- Migoi or Mi-go (strong-, wild- man)

- Kang Admi (snow man)

- Thloh-Mung (mountain savage)

Tibetan names such as

- Rime (forest dweller),

- Me Shornpo (strong man) and

- Megod (untamed man)

are said to be symbolic of the shamanistic elements of Tibetan religion.

Nepal

The origin of the word yeti is ascribed to the Sherpas who used the term before it became known around the world: yah- the spoken Yeti,

- Ban Manchhe (man of the forest) and

- Bun Manchi (jungle man)

- Mirka (wild-man) Local legend holds that “anyone who sees one dies or is killed”.

- Mahalangur (great monkey) are terms used by the Nepalese.

A section of the Himalayas that includes Everest, Lhotse, Makalu and Cho Oyu is actually called Mahalangur Himal which, incidentally, is traditionally believed to be one of the creature’s abodes.

The Sherpas and Tibetans also call it “Metoh-Kangmi” meaning “unwashed snowman”.

The Abominable Snowman

The popular term “Abominable Snowman”, a creation of journalist Henry Newman in 1921 is, in fact, is a misnomer. Newman, who was a contributor for The Statesman in Calcutta, interviewed the porters of the Everest Reconnaissance Expedition (led by Charles Howard-Bury) on their return to Darjeeling in West Bengal.

Bury supposedly had come across large footprints that he believed

“were probably caused by a large ‘loping’ grey wolf, which in the soft snow formed double tracks rather like a those of a bare-footed man”.

He adds that his Sherpa guides

“at once volunteered that the tracks must be that of ‘The Wild Man of the Snows’, to which they gave the name ‘metoh-kangmi’”.

“Metoh” translates as “unwashed” and “Kang-mi” translates as “man-bear or snowman”. The journalist incorrectly translated the word “Metoh” (unwashed) to “abominable”. Newman misleadingly used the name ‘metoh-kangmi’, but it stuck and has been in use ever since.

Myth and folklore of the Yeti

“Long ago there was a beast in our mountains, known to our forefathers as the Thloh-Mung, meaning in our language Mountain Savage.

Its cunning and ferocity were so great as to be a match for anyone who encountered it. It could always outwit our Lepcha hunters, with their bows and arrows.

The Thloh-Mung was said to live alone, or with a very few of its kind; and it went sometimes on the ground, and sometimes in the trees. It was only found in the higher mountains of our country. Although it was made very like a man, it was covered with long, dark hair, and was more intelligent than a monkey, as well as being larger.

The people became more in number, the forests and wild country less; and the Thloh-Mung disappeared.

But many people say they are still to be found in the mountains of Nepal, away to the west, where the Sherpa people call them Yeti.”

~ The Sherpa and the Snowman.

Long before the yeti made its appearance in the memoirs, reports, and travelogues of British officers, naturalists, and journalists, it was a well- known figure in the myths, legends, folklore, and folktales of several communities living in the Himalayas. The yeti has been an integral part of Sherpa and Tibetan myth and religion.

Rumors about yeti mummies being preserved in remote Tibetan monasteries have abounded for centuries. Lama Lopen, who escaped to India with the Dalai Lama after the Chinese occupation of Tibet, claims to have come across a shriveled but relatively well-preserved body of a giant ape in the secret catacombs of the Sakya Monastery near Shigatse in western Tibet.

Scrolls in monasteries place them between animals and humans. According to a Sherpa legend, they are

the children of a Tibetan girl and a large ape

which could be a reason why

they are believed to exist between the human and animal worlds.

The Sherpas regard the children to be bodyguards of Dolma, the female incarnation of Chenrezig. Since Sherpas practice the Nyingmapa sect of Tibetan Buddhism, which retains elements of the pre- Buddhist Bön religion, they believe that a person’s soul moves to the body of nonhuman creatures after dying, which is why yetis are revered by some.

Tibetans consider themselves to be descendants of Chenrezig, the Buddha of Compassion, in his incarnation as a monkey god. It is believed that the god married a demon and out of this union came six children with long hair and tails. Slowly, the hair and tails disappeared due to the blessed grains they were fed. Some of the children, their texts say, inherited their father’s qualities and others those of their mother.

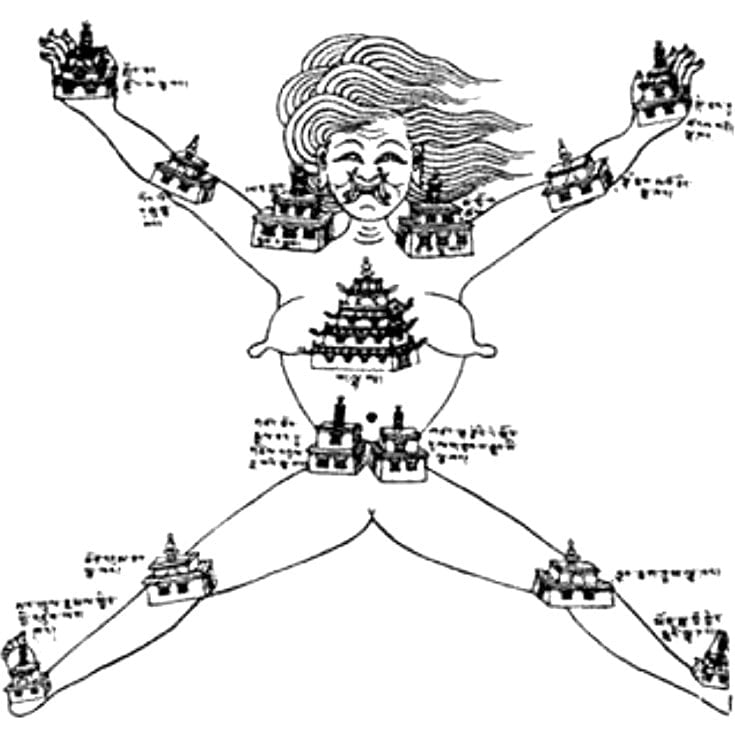

CREATION MYTH: The descent of the Tibetan people from a monkey god and a rock – ogress

For instance, the Mani Kabum (mani bka’ bum), an important twelfth century religio- historical chronicle of Tibet, exemplifies shared kinship between humans and yetis.

According to the Mani Kabum, Tibet was once a giant lake that receded, leaving behind forests, animals, and mountains. The Tibetan people were born on one of these mountains bordering the Yarlung valley. This mountain was inhabited by a Sinmo (srin mo), a female rock ogress, who was an incarnation of the Buddhist deity of mercy Drolma (sgrol ma).

The ogress met a monkey, who was an incarnation of the Buddhist deity of compassion Chenrezig (spyan ras gzigs), and the two mated.

They produced six hybrid monkey-human children who became the ancestors of the original six Tibetan clans. They were short and covered with hair, possessed flat red faces, stood erect, and perhaps had tails.

Over generations the progeny of the six clan ancestors evolved, becoming more human, until they developed into the Tibetan people.

According to Tibetan oral lore, however, some of these early ancestors did not evolve fully into humans and remained ‘wild people’ (mirgod), or yetis.

Yetis are unlike other nonhuman animals, as they share ancestral kinship with humans, but Yetis are not fully human, either. In the Mani Kabum they reside in an ambiguous liminal space, being neither human nor nonhuman.

In the Buddhist textual standard derived from India, there is no intermediate realm between the human realm and the animal realm.

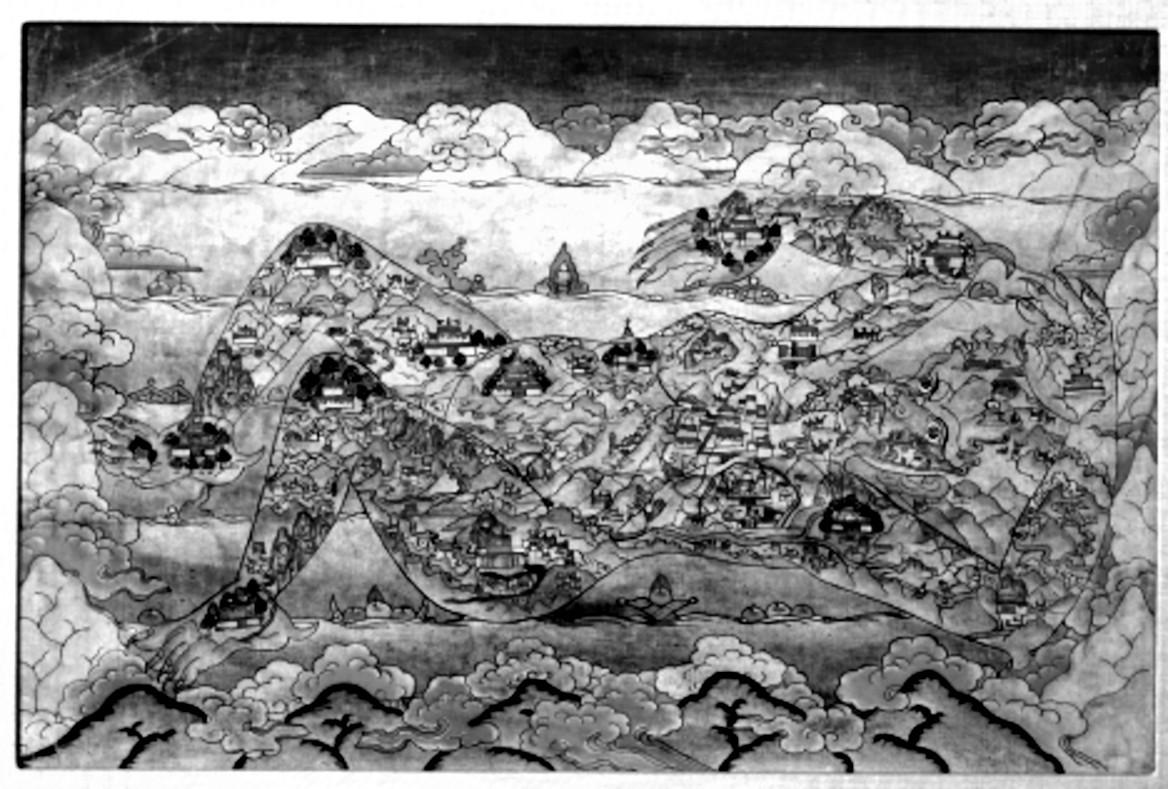

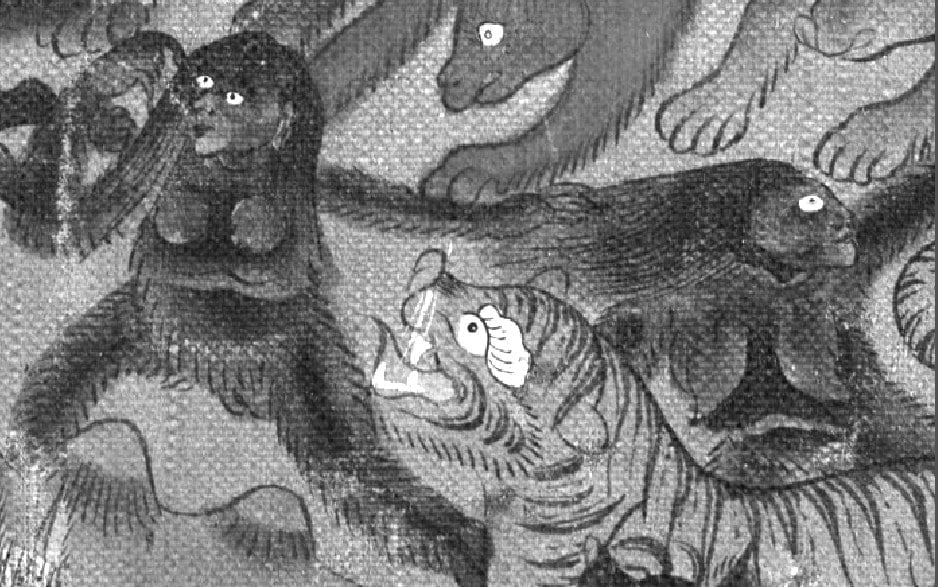

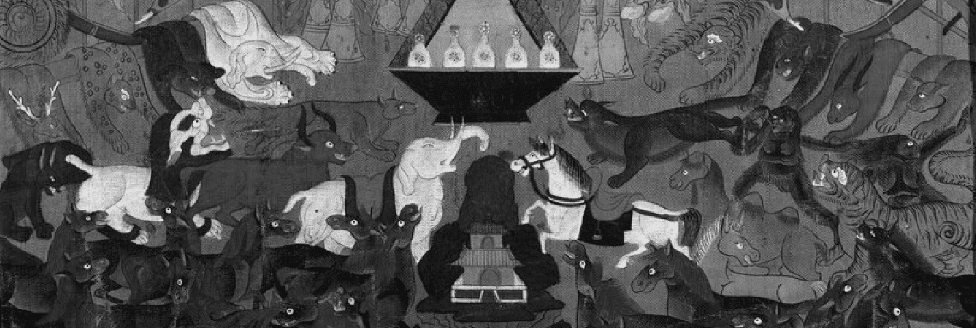

Nonetheless, many pieces of Tibetan temple art, sometimes in mainline monasteries, delineate a ‘yeti realm’ precisely as intermediate between humans and animals, perhaps reflecting the ancestral human-yeti special kinship described by the Mani Kabum.

In Tibetan Buddhism, some kyilkhors (dkyil ‘khor), which are elaborate meditational artworks, and thangka religious paintings in Buddhist temples clearly depict wild man or yetis.

THE YETI IN BUDDHISM

The legend of Sangwa Dorje and Pangboche Gompa

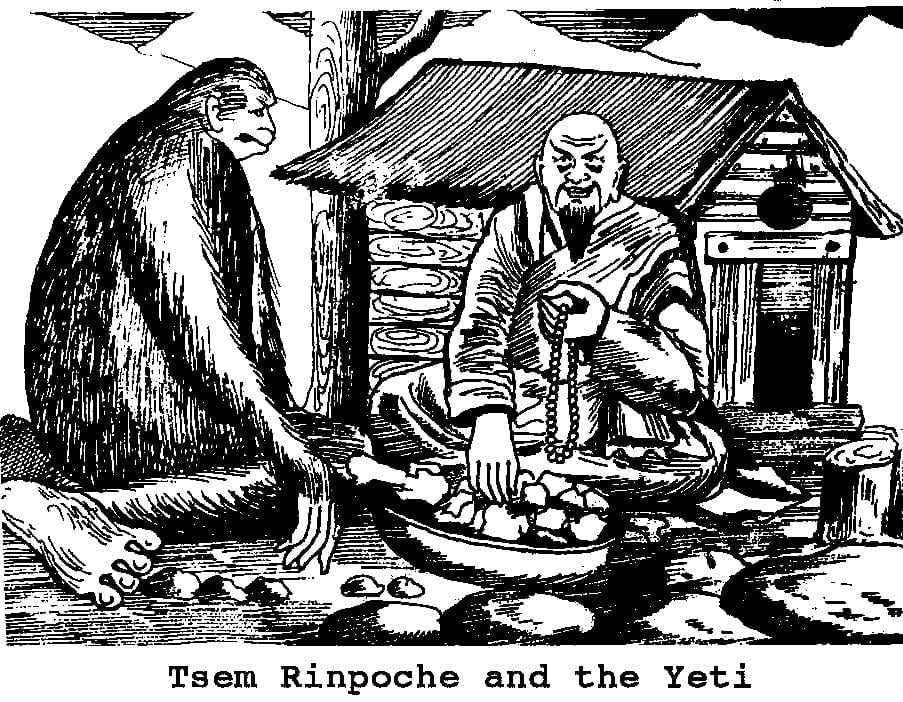

In Tibetan Buddhist areas, people typically revere meditating hermits like Sangwa Dorje and, as a sign of religious devotion, freely offer them food and water in support of their retreats.

It was a yeti who cared for Sangwa Dorje. The yeti regularly brought Sangwa Dorje food, water, and fuel, and even became his Buddhist disciple. When the yeti died, Sangwa Dorje retained the alleged scalp of the yeti and this scalp and a supposed yeti hand remained in Pangboche Gompa, the monastery founded around the year 1667 by Sangwa Dorje.

For centuries afterwards, the Drogon lamas, who are successors to Sangwa Dorje’s leadership, periodically would parade the yeti scalp around the village in a fertility ritual to bless the people, animals, houses, and fields, a practice which continued until the lineage of the Drogon lamas recently moved to India. The yeti hand was housed as a sacred relic of the monastery until it was stolen in 1999.

The ritual use of “yeti” body parts is also found in prescriptions for Bön magical potions which use yeti blood. As remarkable as it is to think that yetis can be Buddhist practitioners, the story of Sangwa Dorje is not isolated and other notions of religious yetis exist.

Yetis serve as Buddhist shrine attendants

Kunsang Choden, for example, recounts a Bhutanese tale in which a group of yetis serve as Buddhist shrine attendants. In the dead of night and away from the prying eyes of humans, a small group of yetis maintained a village temple devoted to the protective deity Panden Lhamo (dpal ldan lha mo). Each night the yetis would arrive, clean and refill the offering bowls on the altar, replenish the butter in temple butter lamps, and then disappear before sunrise. Like the yeti in the story of Lama Sangwa Dorje, these yetis perform Buddhist bodhisattva – deeds and acts of Buddhist devotion.

The grateful Yeti

This story is quite common, possessing several variants across Himalayan communities.

In this legend, a Tibetan Buddhist yogi, wandered through the mountains. Then, one day he was crippled by an attack of gout and was unable to walk. He established himself in a pleasant place at the edge of the forest where he found some goats, who eventually followed him everywhere like pets. There he remained.

On the other side of the hill were some abandoned shacks. Every day he would see a huge dark man coming and going between the shacks and the river. Apart from this, there was no other sign of life.

One week he no longer noticed his strange neighbor on his daily walk. Having become intrigued by that mysterious man and feeling a bit better, the yogi decided to investigate the man’s dilapidated dwelling.

Inside, the yogi was startled to come face to face with a migö, or wild man, as Tibetans call the yeti. The hirsute behemoth was lying outstretched on the floor, eyes closed and fangs apart, seemingly unaware of the intrusion.

He was feverish and obviously ill.

One of the yeti’s feet was grossly swollen and full of pus. The yogi immediately noticed, protruding from the infected area of that vast foot, a sharp splinter of wood that could easily be removed. He thought,

‘I know he can jump up and devour me at any moment, but now that I have come this far I might as well try to help the poor creature.’

While he gently extracted the long splinter, the yeti – aware that the lama was helping him – lay as still as a patient etherized upon an operating table. The kindly yogi cautiously cleaned away the pus. He washed the wound, using his own saliva as a salve; then he bandaged the bizarre foot with a rag torn from his own clothing.

On tiptoe he left the yeti, returning to his goats, which were tied to a tree in the forest.

Days afterward, he saw the yeti limping down to the river, presumably for water, and then slowly returning to his house. Eventually the creature’s gait improved to the point where he could walk without difficulty.

Miraculously enough, the yogi’s crippling gout also began to subside so that his painful stride began to return to normal, until he, too, was completely cured.

After that, he no longer saw the yeti.

One day the ferocious yeti suddenly leaped down like a giant gorilla from the trees, grimaced at the yogi, then sprang back into the trees and was gone.

A few days later the same thing happened – but this time the yeti was carrying a dead tiger on his shoulder. Placing the magnificent carcass in front of the lama as if in a token of his gratitude, he again bounded off into the dense jungle.

The yogi did not wish to eat the meat, but he skinned the beautiful beast with meticulous care. Eventually, upon his return to the Shechen Monastery, he offered the splendid tiger skin to the monastery for use during tantric rites.

Yeti in ceremonies

During the Dumche ceremonies a figure called a gyamakag (rgya dmag ‘gag or rgya ma kag) guards the monastery entrance. The gyamakag is a human who ‘represents a yeti and his role is to scare away evil spirits, who are said to be extremely afraid of yetis’. In this performance as a yeti the gyamakag wears the conical yeti scalp kept at the monastery, a sheepskin coat turned with the fur on the outside, and has his face painted black. This yeti also helps to disperse negative forces from the community, this yeti represents a divine religious ally who is pacific towards humans.

Yeti as mountain deities

But Yetis are also dangerous to humans, but the most threatening may also be the most divine, emerging as incarnations of mountain deities in the context of Himalayan folk religion.

Many Himalayan people consider a great mountain in their vicinity to be the abode of their local yul lha, or ‘locality deity.’ In fact, in Tibetan folk belief great mountains are deities who happen to appear as mountains. Such yul lha deities reward the local community for good behavior and discipline it for negative behavior, thus keeping order in social groups through various taboos and restrictions.

It is widely thought that a displeased yul lha will distribute punishment by sending out a physical embodiment of the deity, in the guise of a strong ape-like yeti. This mountain deity yeti, as a continuation of the raksha (Tibetan gnod sbyin) of Indian Hindu and Buddhist myth, enforces discipline by bringing illness, property damage such as crop destruction or depredation of livestock, or human death.

This is why among the many Buddhist artworks of the revered Drepung Monastery in Lhasa, Tibet, one finds a mural painting of a she-yeti carrying a decapitated human corpse.

Because mountain deity yetis function as keepers of community order, Himalayan people frequently regard hearing or seeing a yeti as a bad omen and some mountain dwellers may seek the aid of a Buddhist leader to dispel negative forces and accumulate merit if they have encountered a yeti.

LEPCHA Myth and Folklore of the Yeti

The Lepchas are said to worship the yeti as the ‘spirit of the hunt,’ and regard him as the master and protector of all animals, who live in the mountain-forests.

The link between the yeti and a similar figure that appeared among the Lepchas was noted by Nebesky-Wojkowitz in 1957:

The most curious figure in the Lepcha pantheon is Chu Mung, the “Glacier Spirit,” an apelike creature. This is no other than the mysterious Yeti, or “Snowman,” of the Sherpas and Tibetans.

Nebesky-Wojkowitz

The Lepchas worship the Glacier Spirit as the god of hunting and lord of all forest beasts. Appropriate offerings have to be made to him before and after the chase, and many Lepcha hunters claim to have met the Glacier Spirit during expeditions on the edge of the moraine fields

Some stories tell of the lord of the animals, being feared by the Lepcha- being pelted with stones and boulders, having trees fall on them, and shivering and shaking in terror upon hearing the eerie whistle of the mung:

It’s up there. […] If you come across a female one, you are lucky.

A male could kill you! Seeing a female Jhampey Mung means that you will never return empty handed from your hunt. They whistle and that’s how you know it’s them. They could be this tall [suggests a height of around 3.5 feet with his hand] and have red hair. They have red hair and look like us. […]

They are appeased by an offering of ginger, dried bird and fish. The males can be violent and throw big stones around your shed. You hear a whistle near you and in a moment you start hearing whistles from all the mountains around you.

They are the mountain deities and we must appease them.

They are our Great Spirit Guides in the mountains.

BHUTANESE Myth and Folklore of the Yeti

A character that frequently appears in Bhutanese folklore is the migoi (from Tibetan mi rgod), a magical creature of the wilds that is simultaneously a supernatural being and a creature invoked to scare children. It shares several of the characteristics already attributed to the yeti-like creature in the Eastern Himalayas and has some additional traits: it can become invisible at will, its blood has magic qualities, and can be used to create talismans, amulets, and magic weapons.

In Bhutanese sources two different kinds of yeti-like beings are found:

the mechume, also known as mirgola, which was usually described as a small, hominoid, ape-like being with long arms and brownish or reddish hair who inhabits the deep, forested slopes of the Himalayas, and

the migoi or gredpo, who usually stalks the high pastures where the herders bring their yaks. The migoi is described as a huge being with reddish-brown or grayish-black hair.

In certain tales the migoi is said to have a hollow back. This detail is quite interesting since, like the description of the reversed feet reported in other contexts, it seems to point toward the world of the dead: in India and Nepal, reversed feet and a hollow back are features commonly associated with very aggressive and dangerous ghosts.

In Bhutanese folklore, the being also possesses some magical items: the dipshing, a kind of charm in the form of a juniper twig, which gives the holder the power to become invisible at will, and the sem phatsa, a small satchel without which the migoi becomes helpless and loses all its powers.

SIKKIMESE Myth and Folklore of the Yeti

Among the Lhopo villagers of Tingchim, the yeti is equated with the spirits of mountain passes, the latsen:

The latsen is one of the most important and versatile class of supernatural being in Tingchim. […] the latsen are usually heard or smelled rather than seen. They are well-known for helping practitioners with logistics during the isolation of their meditation retreats by presenting firewood and meat at their doorstep, and may be protectors of women in the village.

Although helpful, the latsen are also thought to be at the root of many cases of illness in the village.

Moreover, Sikkim is considered to be a “hidden land”, a secret and sacred place, blessed by Guru Padmasambhava and filled with relics, treasures, and medicinal herbs. In a text explaining the wondrous nature of the environment and the auspicious qualities of the landscape, it is said that:

Whenever the mountains, rocky hills, lakes and small streams of such a sacred land are polluted, its native guardian spirits and local deities will become agitated.

- When mdZod lnga becomes agitated, there will be harm from a tiger.

- When it is Thang lha, there will be harm from the yeti (mi rgod).

- When bdud becomes restless, there will be harm from a wild bear.

- The nagas will send harm by a poisonous snake,

- btsan will cause harm through a wolf or a wild dog.

In short, whenever the native guardian spirits and local deities are not honoured, rain will not come on time human and animal diseases will occur as well as internal unrest, causing all kinds of hardship and suffering.

Ban Jhakris of Sikkim – The forest shamans

The Ban Jhakris is the Nepali name given to the small yeti (three to five feet tall) whose red or golden hair covers his entire body except for face and hands.

The forest shaman and ascetic, is often described as a small, furry being with reversed feet who is known to act as a teacher for future shamans, imparting to them specific knowledge about the spirit world and how to deal with it.

According to legend, ban jhakris live in forests and caves and kidnap young candidates, typically between seven and twenty years of age, to initiate into shamanism. Only those youths who are chokho (pure) in body and heart are retained for teaching, ideally for thirty days, before being returned to the place from which they were initially abducted. Candidates with physical scars or impure hearts are released quickly, often violently “thrown” from the ban jhakri’s cave, or worse, captured by his big and ferocious wife, the ban jhakrini, who desires to cannibalize the young initiate.

Some consider the yeti to be disciples of Shiva and are thought to be spirits from the Sun. The Ban Jhakris (supernatural shamans of the forest and caves) too are said to be ardent followers of Shiva although the extremely long hair they possess are reminiscent of those worn by the ancient Tibetan Black Bön shamans.

SHERPA Myth and Folklore of the Yeti

In 1997, Sherpa and Peirce published an account of one encounter between the informant’s father and a yeti.

At that time, my father went to cut grass on a hill. From Orsho, you walk down, down, down – and cross the river from Thamo. Then up the hill and go to cut the grass. He had a basket – a big basket – and he took some kind of sharp hook that they have for cutting grass.

It was then the middle of the day. Then he smelled a very, very bad smell – VERY bad smell. He sniffed again, and this time, it’s a very bad smell. And he’s walking up the mountain and looking and he’s saying, “What is going on here?” He is just looking everywhere, and then he sees the yeti.

The yeti is going up then. And then he came down. But my father saw him first. The yeti was sitting on a rock. He was quite close from here to down there – you see that small tree?

That much far, I think. Yetis aren’t so big. They are about the size of seven-year-old people. But yetis are VERY strong. I have never seen one. My father has told me about them.

This one is sitting on a rock up on the mountain. He isn’t walking, just sitting there on the rock.

My father saw him before he saw my father. If the yeti had seen my father first, my father wouldn’t have been able to walk. The yeti can make people so they can’t walk. Then he eats them. But this time my father saw the yeti FIRST. He didn’t bother about picking up his basket or his robe or that hook – the sharp hook. He just started running, running, running.

The encounter is a dangerous one, since the being has some power: if he sees you first, you cannot move, and then he will eat you. The yeti is also smelled before actually being seen.

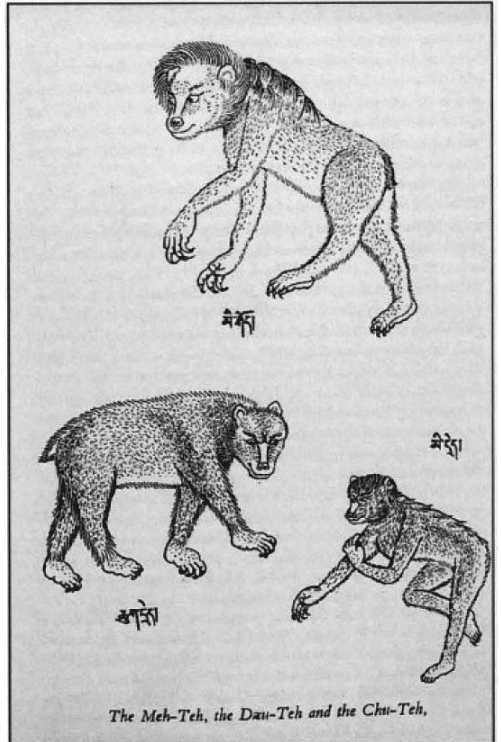

The expression seems to define a bear-like being (dred) that inhabits the higher Himalayas, and in Sherpa folklore at least three different types of this bear-like being are identified:

1) drema or telma (Tib. dred mar);

2) chuti (Tib. phyugs dred), and

3) miti (Tib. mi dred or mi teh)

The drema or telma has red, gray, or black fur; about the same size as monkeys, they seem to live in groups. Seeing them is considered a bad omen, and their cries are a sure sign of disaster: their call is reputed to bring misfortune, disease, or a death in the family.

The chuti are described as bear-sized creatures covered in black, gray, or dark red hair. They usually walk on all fours and prey on cattle: they are known as killers of sheep, goats, and yaks.

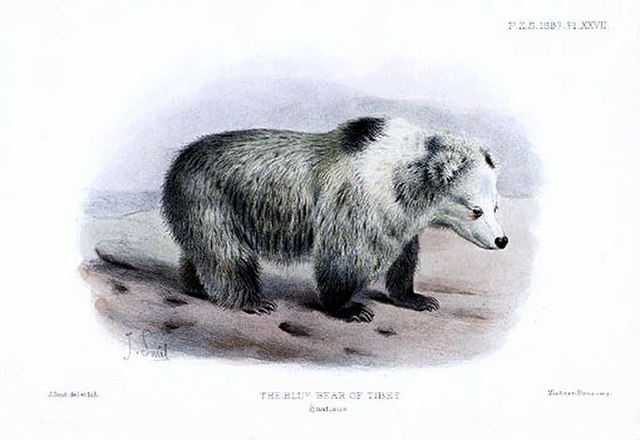

According to biologist Charles Stonor, the drema and the chuti is the Himalayan red bear (Ursus arctos isabellinus) or Himalayan brown bear (Ursus arctos), and some Sherpas recognize it as such.

The miti seems to be the size of a man with a reddish or light blond fur, a pointed head, and hair falling over its face. It walks upright, and is known to kidnap humans.

The miti for some Sherpa people is not a bear at all.

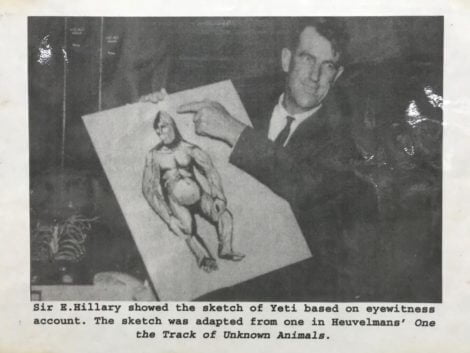

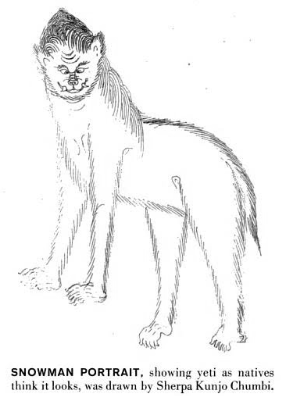

Illustration of the Abominable Snowman or yeti according to locals from the Himalayas.

Source: Epitaph to the Elusive Abominable Snowman. LIFE Magazine. 13 January, 1961, Author Sir Edmund Hillary.

Public domain, edited.

YETI – Historical descriptions

The tales change from region to region across Asia – yetis were man-eaters in some places, grass-eaters in others.

In many mountain reagions, the beast was seen as a harbinger of death, a combination of man, animal and demon.

Pliny the Elder

Among the mountainous districts of the eastern parts of India, in what is called the country of the Catharcludi, we find the Satyr*, an animal of extraordinary swiftness.

These go sometimes on four feet, and sometimes walk erect; they have also the features of a human being. On account of their swiftness, these creatures are never to be caught, except when they are either aged or sickly. Tauron gives the name of Choromandæ to a nation which dwell in the woods and have no proper voice. These people screech in a frightful manner; their bodies are covered with hair, their eyes are of a sea-green colour, and their teeth like those of the dog.

* These are the great apes, which are found in some of the Oriental islands; this name was given them from their salacious disposition, which, it would seem, they have manifested in reference to even the human species. We have an account of the Satyrs in Ælian, Hist. Anim. B. xvi. c. 21 – B.

Chinese and Tibetan Manuscripts

Chinese manuscripts from the 7th century mention hairy creatures similar to the yeti that might be Babboons, Orang-Utans and Pandas also.

Shan gui (山鬼), Yeren, Yeti? Vectorization of an illustration from the Chinese encyclopedia Gujin Tushu Jicheng, section “Borders” 1700 and 1725. Public domain, edited.

Perhaps the earliest mention of a human-like monster appears in a poem (Jiu Ge) by Qu Yuan (340–278 B.C.) that describes a shan gui (山鬼), a “mountain ghost” as “like a man … wearing fig leaf”.

A Qing dynasty commentary on this poem (undated, but likely eighteenth-century) adds an explanatory note: “hill ghosts can generally be included as a kind of kui,” a word that means “resembling a man.”

It has been argued that Qu Yuan in his poem is describing a manlike creature who wears fig-leaves as clothing. This interpretation, however, is disputed by scholars who argue the monster is a demon or ogre.

Tang dynasty era (618–907 CE), e.g., Li Yanshou in Nan Shi (History of the Southern Kingdoms, c. 650) wrote about a group of maoren (“hairy men”), who climbed a city wall. Duan Chengshi in his Youyang

Zazu (a miscellany on legends, 853 CE), describes the feifei as follows:

If you drink the blood of the feifei, you will be able to see ghosts. It is so strong that it can shoulder one thousand catties … its upper lip always covers its head. Its shape is like that of an ape. It uses human speech, but it sounds like a bird. It can foretell life and death. Its blood can dye things dark purple, and its hair can be used to make wigs.

Legend has it that its heels face backwards … hunters say that it has no knees.

Since at least the eighteenth century and likely much longer, many Himalayan peoples have understood yetis as real creatures and yeti reports have continued into the twenty-first century.

- Tibetan cultural images describe yetis as ape-like rather than bear-like, with long arms, a powerful torso, a conical head, and a body covered in long brown or reddish hair.

- The hairless face of a yeti has a flat nose, like a primate, rather than the protruding nose of a bear.

- A yeti may move on either two or four legs depending on the ease of journey.

- All Yetis are hairy and very strong. Although both the small being and the large one have hairy bodies, the small one is a reddish or yellowish brown while the big one is dark brown, gray, or black.

- Such beings are often said to emit a characteristic sound that is almost like a whistle. Some aver that yetis possess their own language.

- Females are the leaders of yeti groups.

- Yetis are thought not to live in the high altitude snows but rather in the alpine forests just below the snow line. During winter they move to lower altitudes and nearer to human settlements, but they may travel across high altitude snowfields to move to a different valley or to feed on the saline mosses of the glaciers, yetis are thought to feed on frogs and pikas, the abundant small mouse-hares found widely in the Himalayas.

- Humans almost invariably encounter these beings in forested areas or snowy fields, although some reports claim they can raid cultivated fields, destroy crops, or attack cattle. In some of the accounts gathered by anthropologists, they are also known to prey on humans.

- In addition to these zoological traits, in many folktales and local accounts the yeti also has inverted footprints, can kidnap human beings in order to mate with them, and usually imitates human behavior.

- Numerous legends are told also about the “man-bear”, who is believed to carry off sometimes a man or woman, keeping his victim in an inaccessible cave, the prisoner being mostly able to escape only after many years of captivity.

The Hunt for the Yeti

“The Yeti is alive, but one will never see him. One can feel him,

but one will never grasp him.”

Oppitz Michael. Geschichte und Sozialordnung der Sherpa. 1968.

Just maybe, some thought, there could be truth in Myth and Folklore of the Yeti. The high Himalayas are among the most isolated, forbidding parts of the world. Couldn’t something – perhaps a species of big ape, an ancient bear or even a form of proto- human – have hidden for centuries amid the crags?

In 1954, Britain’s Daily Mail newspaper sent out a search party. In 1957, a Texas oilman took up the chase.

Three years later, Everest conqueror Tenzing Norgay and Sir Edmund Hillary searched along the Nepal-Tibet border. In their wake came other expeditions, TV crews, scientists, military, merchants and marketer.

Plenty of tempting clues have been found, from holy relics, footprints to hair.

But science can explain – they often turn out to be from bears – and five decades of searching has turned up – nothing. Eventually, even many fervent yeti hunters see the truth in more prosaic explanations.

Tenzing Norgay and Sir Edmund Hillary traveled to the United States, then to France and Great Britain with a yeti scalp. Scientists examined it and all concurred that it was fabricated from the hide of Antilocapi Sumathiensis: the serow goat. The scalp was returned to the people and gompa of Khumjung, where it remains to today.

Anyway, the mountain communities don’t need scientific proof to believe in the existence of the Yeti who shares their barren habitat with them. He is an integral part of their folklore. And he’s best left alone.

Any Lepcha or Sherpa can tell you that you should run downhill to avoid getting caught by a Yeti. As the animal chases you down a sharp incline, the wind will blow his long hair into his eyes and it’s only when he’s momentarily blinded that you can give him the slip.

They have a vile, pungent odour, and according to local superstitions, they have supernatural powers. A sighting will invariably bring bad luck, ill fortune or death – it can eat you.

The Sherpas also believe that organized expeditions to hunt down the Yeti will never bear fruit. The animal can disappear at will and it is only by accident, when he’s caught unawares, that you can see him. As many in their numbers have.

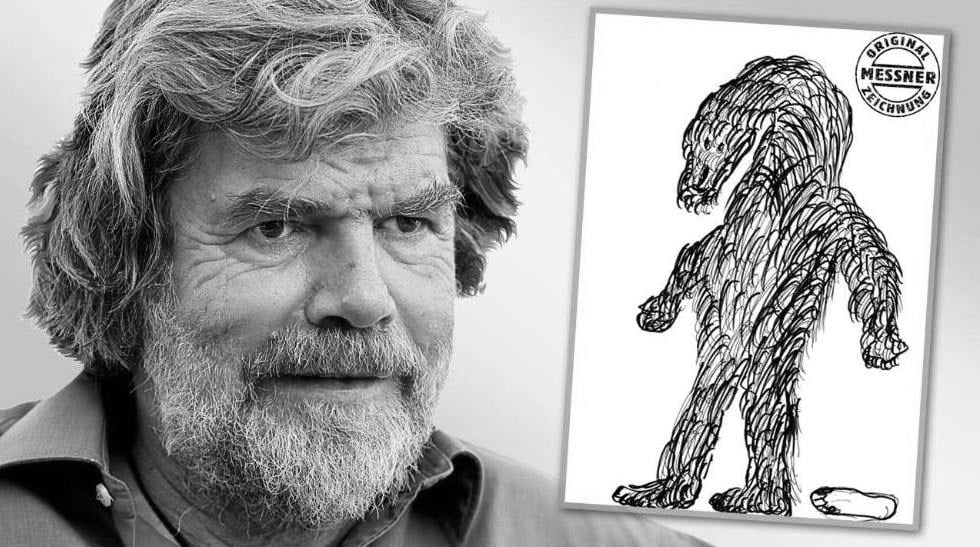

The great Italian – Tyrolean climber Reinhold Messner spent years tracking yeti stories across the Himalayas and even caught a glimpse of it a couple of times. But in the end, the truth was obvious to him.

“All evidence,” he wrote at the end of his travels,

“points to a nocturnal species of brown bear.”

– Or maybe not.

Tibetan blue bear (Ursus arctos pruinosus). Joseph Smit. Public domain, edited.

We did not explore remote areas to hunt for the Yeti, but we could comfortably visit a small exhibition at the International Mountain Museum in Pokhara.

~ ○ ~

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- Anthropological perspectives on folklore: underpinnings on some Nepali folklore

- Capper Daniel S.The Friendly Yeti. University of Southern Mississippi. Faculty Publications. 2012.

- Dutt Nabanita. The Himalayan Yeti – Believe what you will. 2002.

- http://thingsasian.com/story/himalayan-yeti-believe-what-you-will

- Messner Reinhold. My Quest for the Yeti: Confronting the Himalayas’ Deepest Mystery. 2000.

- Lan, T., Gill, S., Bellemain, E., Bischof, R., Nawaz, M.A., & Lindqvist, C.Evolutionary history of enigmatic bears in the Tibetan Plateau–Himalaya region and the identity of the yeti. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.1804

- https://sino-platonic.org/complete/spp309_chinese_wildman.pdf

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History (English)

- Prakash Upadhyay.Tribhuvan University·Department of Anthropology, Tribhuvan University, Nepal, Prithvi Narayan Campus, Pokhara

- Sawerthal Anna and Torri Davide. Imagining the Wild Man: Yeti Sightings in Folktales and Newspapers of the Darjeeling and Kalimpong Hills. 2017. https://www.academia.edu/35434877/Imagining_the_Wild_Man_Yeti_Sightings_in_Folktales_and_Newspapers_of_the_Darjeeling_and_Kalimpong_Hills

- Stonor Charles. The Sherpa and the Snowman. 1955.http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/rarebooks/downloads/Sherpa_and_Snowman.pdf

- The International Mountain Museum (IMM) in Pokhara. Nepal.www.internationalmountainmuseum.org

- The tale of the yeti. https://www.tsemrinpoche.com/tsem-tulku-rinpoche/science-mysteries/tale-of-the-yeti.html

- Vishal Rai. A Matter Of Religion. Sherpa and Tibetan mythology.

- Vishal Rai. The mysterious Yeti. 2014. http://ecs.com.np/features/the-mysterious-yeti

- Yeti. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

- Yeti. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rspb.2017.1804

Keep exploring: