Folklore of 熊猫 – the Giant Panda, has its roots in Tibetan and Chinese culture. Read the legends on how the panda got his black marks, discover its etymology and symbolism and the use in traditional Chinese culture. Discover the History and Mythology of the xióng māo, Mo, Pixiu or Giant Panda.

In this Article

Giant Pandas 🐼 are regarded as “sacred creatures of the forest” and “Living Fossils” and are the only mammal to have survived the Pleistocene, three million years ago, going back to the time of the saber-toothed tiger.

Chinese people adored these gentle giants, regarding them as a symbol of peace. As such, they are offered as valuable gifts to royalty or politicians and a gesture of goodwill to foreign countries, till today.

Considered symbols of strength and bravery, the early Chinese emperors kept them to ward off evil spirits and natural disasters and warriors were often compared to giant pandas.

Cultural History and Mythology of the Pixiu, Xióng māo, Mo, Pixiu, or Giant Panda

LEGEND: The Pandas and the Shepherdess or

How the Panda got his marks

Once upon a time a beautiful shepherdess called Dolma; lived in Wolong Valley, beloved by everyone for her kind heart. The shepherdess always took her sheep into the hills surrounding the valley and every day a young panda bear cub, back then known as beishung would join her flock.

In those days pandas were all white so possibly the panda thought the sheep were other pandas.

However, one day the panda cub was gamboling with the sheep and lambs but suddenly a leopard attacked the panda. The shepherdess grabbed a big stick, and in turn attacked the leopard. The panda was able to escape from the jaws of the leopard but the leopard killed the beautiful young girl.

The other pandas heard of this terrible event and mourned the beautiful shepherdess who had saved the panda cub. They all came to her funeral and to show their respect they covered their arms with ashes, as was the custom at that time.

The funeral was a very sad affair and the pandas were overcome with grief and sadness.

They sobbed and wailed, sobbed and cried out in their painful sorrow, wiping their eyes with their paws. They cried so hard and their sadness was so loud that they covered their ears with their paws to block out the noise. Wherever they touched their white fur, the ashes stained their fur black.

That is why to this very day, all pandas bear the dark marks of the ashes on their fur in memory of the kind and loving shepherdess. The shepherdess’s three sisters also overcome with grief and sorrow, threw themselves into her grave.

The earth rumbled and shook and a huge mountain sprang up from the grave. That mountains, still stands there today and is known as the Four Sisters’ Mountain (Siguniang). Each sister was transformed into one of its peaks, guarding and protecting the panda bears to this day.

A Tibetan Variant of the legend: How did Giant Pandas come to have such unique color markings?

Long, long ago, the Giant Pandas lived in the high mountains of Tibet. Their fur was completely snow white. They were friends with young shepherdesses, who watched their flock in the mountains around their village.

One day a mother and her cub were playing with the shepherdesses and their flock when a strong and hungry leopard attacked the cub. The shepherdesses tried to save the cub but were unsuccessful and the leopard killed them.

All the Giant Pandas in the area were very sad and held a memorial service for the shepherdesses and to remember their sacrifice for the cub. The local custom in the mountains was to cover your arms with ashes to honor the deceased.

The Giant Pandas wept. They wiped their eyes with their paws, covered their ears to block the sounds of crying and hugged each other for comfort. The ashes blackened their fur. The Giant Pandas did not wash the black off their fur as a constant reminder of the girls.

Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuaries

About 20000 – 30000 years ago, pandas were distributed across 16 provinces of China, including near Beijing. Today, wild giant pandas live only in three provinces, Sichuan, Shanxi and Guansu with eighty percent of the animals living on the Chengdu Plain in Sichuan.

China made giant pandas a protected species in 1962, the first captive-bred panda cub was born in 1963, and poaching was criminalized in 1987, setting strict new penalties of at least ten years in jail or even death. In 2005, the Chinese government created over 50 panda reserves in a conservation effort to preserve their national emblem.

The UNESCO world heritage site, Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuaries, are home to other globally endangered animals such as the red panda, the snow leopard and the clouded leopard. They are among the botanically richest sites of any region in the world outside the tropical rain forests, with between 5000 and 6000 species of flora in over 1000 genera.

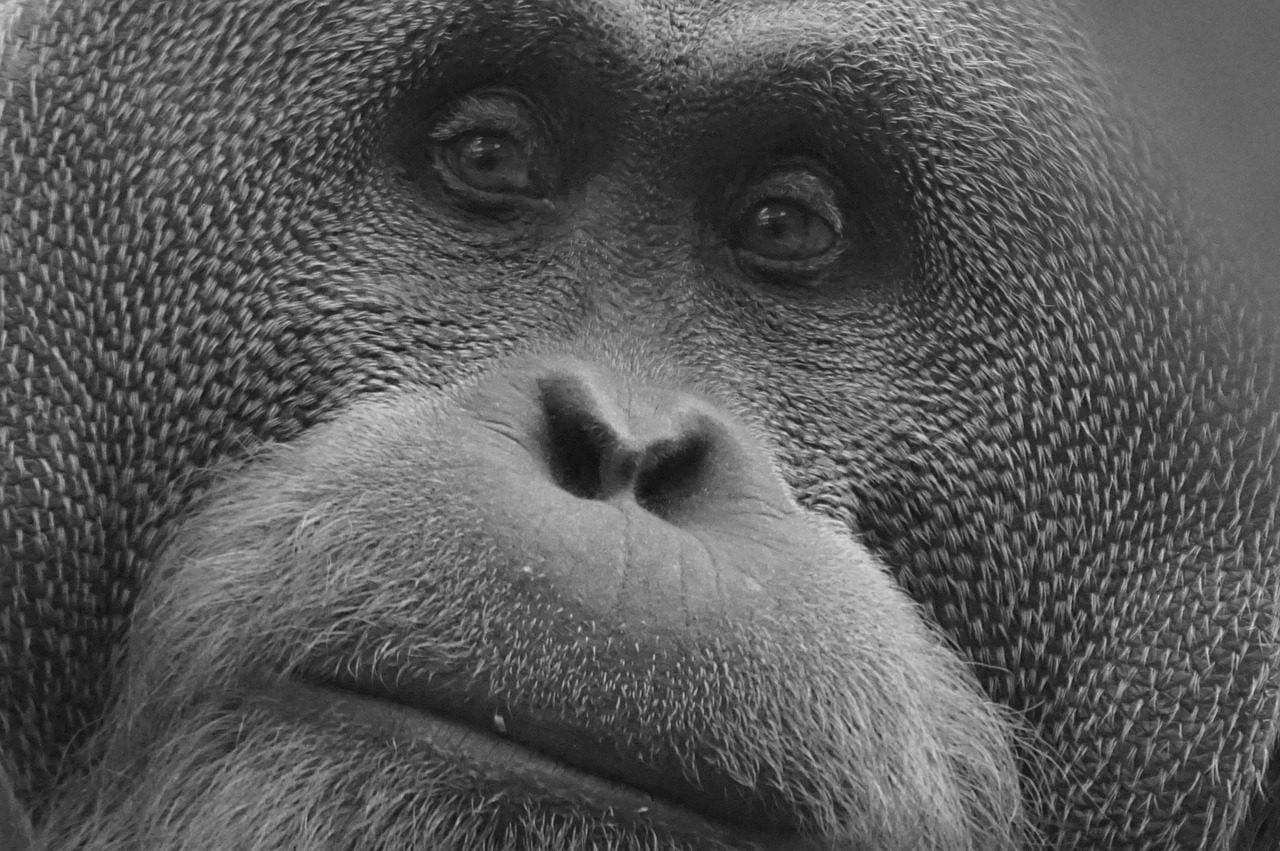

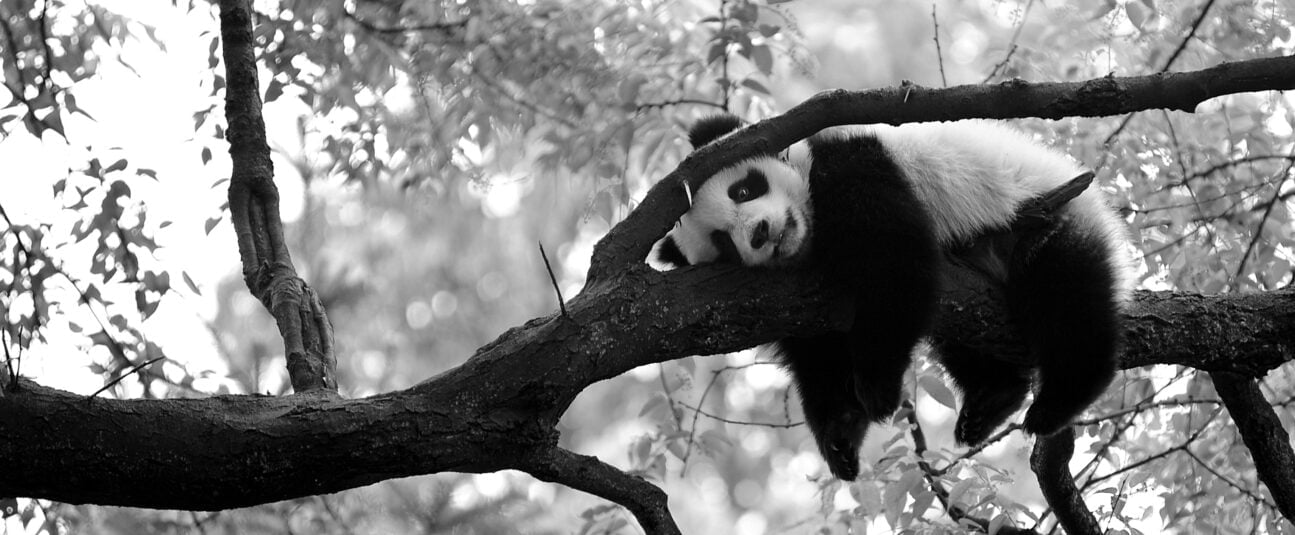

The Chengdu’s Research Base we visited, houses more than 100 giant pandas in an immaculately landscaped park. Though the pandas mostly stay inside during the hottest summer months, the rest of the year they live outdoors in spacious playpens. During our visit we witness how they spent the day: chewing on bamboo shoots, climbing trees, sleeping and excreting waste.

The museum at Chengdu has recorded the panda daily intake of about forty kilograms of bamboo shoots and an enterprising researcher had meticulously noted that this involved 150 droppings/day!

I thought pandas are slow, calm animals, but at feeding time they got very active, especially the cubs frolicked – rolling around and chasing each other up trees, with one even doing a backward flip on a log platform.

Most of the older pandas were snoozing, on the ground or perched in trees, the babies, tiny, blind, and pink, with few hairs, are on display in breeders.

PANDA: Etymology and Symbolism

The giant panda, because of its much wider range of distribution, had more than a dozen regional names, such as Pixiu, Mo, Zouyu, Whitebear, Flowery-bear, Linyun – cloud in the forest and Iron-eating Animal.

They are also called Chinabear, Bamboobear, Silverdog and Giant raccoon.

- The name giant raccoon came into being because the giant panda has a close blood relationship with a raccoon (even now, some scholars tend to classify it into the raccoon class), but the panda is bigger than the raccoon.

- The name silver dog appeared because the Red Pandas are locally called golden dog, so giant pandas with white hairs are called silver dogs.

- Bamboo-bear, we can easily guess, is because the giant panda eats bamboos; and

- Chinabear was given to it because it is a rare animal peculiar to China.

PIXIU

It is written in the Annals, Biographies of Five Emperors, that 4000 years ago, Emperor Huang used to have pandas (pixiu – ancient name for the Giant Panda) for the purpose of fighting.

The famous Chinese historian Sima Qian of the Han Dynasty notes in Records of the Five Emperors, as early as 4000 years ago, a head of a tribe, called Huangdi, used tamed wild animals to defeat another tribe headed by Yandi at Banquan (now Zhulu County of Henan Province). Among these animals, there were tigers, leopards, bears and 貔貅 Pixiu.

Shang Shu (A High Official in Ancient China) and the Book of Poetry compiled in the early years of West Zhou Dynasty also recorded that the skin of the Pixiu was a tallage of rarity for the emperor. Giant Pandas were considered an animal that was brave and mighty as tigers and leopards; for that reason, ancient warriors were compared to Giant Pandas, whose name Pixiu was used to symbolize victory in all wars.

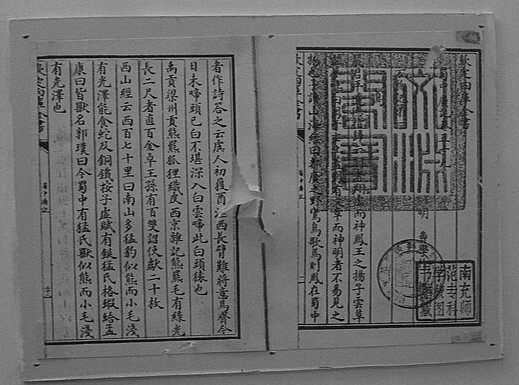

In the Book of Mountains and Seas, a classic of the Spring and Autumn and Warring States Period (2700 years ago), the Giant Panda is described as:

with white and black fur, it looks like bear; and found in Yandao County of Qionglai Mountain

(the present Rongjing County, Sichuan Province).

When the great poet of Tang Dynasty Bai Juyi was resting in a quiet residence, he felt cold and had a headache because of the chilly wind. Someone then gave him a screen on which a giant panda was painted.

The bamboo screen brought about a magic effect to drive out his illness. Loving it very much, Bai Juyi wrote a poem, Ode to a Pixiu on the Screen. By saying that giant pandas need a peaceful environment for survival, the poet expresses his concern about the misfortunes and famines brought to the common people by wars. Bai Juyi considered that pandas had mystical powers capable of making natural disaster go away or evil spirits disappear.

MO

Essayist Sima Xiangru of the Han Dynasty (2000 years ago) recorded in On Shanglin Garden, the Emperor Hanwu once had many fowls and animals in Shanglin Garden for the emperor’s hunting, and Mo (Giant Panda) was among the most important animals.

Ancient texts in China tell of a strange beast with remarkable toughness, whose name – 獏 – has been variously transliterated as “mo,” “mé,” or “mih”. This creature had teeth strong enough to bite through iron, copper, and the joints of bamboo, and could chew the nails off a city gate, its stomach acids could easily dissolve these tough items.

Hench the name Iron-eating Animal. Mo were said to have lived in the areas of Sichuan and Guizhou (especially on Mount Emei in Guizhou), and sometimes ate tripods and cooking utensils if these were mistakenly left out by travelers.

The Mo was also believed to consume snakes and other reptiles. Its bones were said to be nearly solid, with very little space for marrow; and their teeth were strong enough that axes and knives could be broken trying to cut them; the teeth could not be destroyed by fire.

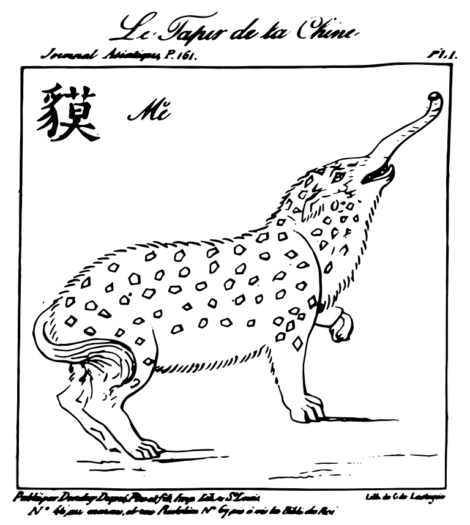

It is also said, that people feared pandas and described them as metal-devouring black-and-white “tapirs”.

The Malayan tapir is likely the animal that the elephant-nosed panda was based on, because tapirs have a pig-like snout which could easily be imagined as a longer trunk; and the Malayan tapir in particular has the dark-light-dark coloration pattern described for the panda.

Later texts describe the Panda as having a nose like an elephant, eyes like a rhinoceros, a tail like an ox, and paws like a tiger.

Chinese manuscripts from the 7th century mention hairy creatures similar to the yeti or leopards, that might be a panda also.

… there are many ferocious leopards in the southern mountains that look like bears but have small fur…

ZHOUYU

In the West Jin Dynasty (1700 years ago), Giant Panda was called 周瑜 Zhouyu. For it eats bamboo only, and does not hurt other animals, so it was seen as an “animal of justice’, that is, an animal of peace and friendliness.

When warring armies took to the battlefield, if one army raised a flag with an image of the Zhouyu, the battle would immediately be called to a halt and a temporary peace would ensue.

WHITEBEAR

According to the Imperial Yearbook of Japan, on October 22, 658 AD, the Empress Wuzetian sent a couple of Whitebears (Giant Pandas) and 70 pieces of panda fur to Emperor Tianwu of Japan.

To this day, the panda continues to be a symbol of peace, and China has gifted pandas to many nations, such as Soviet Union, Japan, North Korea, United States, Britain, France, Germany, Spain and Mexico, as a gesture of peaceful relations.

XIONG MAO

The Name 大熊猫 Da Xiong Mao (Giant Bear-Cat) is generally used in China, and came from the original name Mao Xiong (Cat-Bear) or Da Maoxiong (Giant Cat-Bear), which referred to the round face like the cat and the fat figure like a bear.

Most bears’ eyes have round pupils. The exception is the giant panda, whose pupils are vertical slits, like cats’ eyes. It is these unusual eyes that maybe inspired the Chinese to call the panda the “giant bear cat”.

Later on, the Chinese writing system underwent a reform, so, 熊猫 Xiong Mao became the Chinese name of Giant panda, so the Chinese official name of the Giant Panda became Xiongmao.

OTHER NAMES FOR THE PANDA

The local name of the giant panda around Chengdu, however, is still white old bear or flowery bear.

In the Mingshan Mountain areas of the Tibetan people, it is called Dang or DuDongGa, or DongGa called by the BaiMaBuDa people of Pingwu County, or Equ called by the Li people of Liangshan Mountain. All of these local names, retain the meaning of a white or white-and-black bear-like animal.

One of the few candidates for the root of the word panda is “pónya” or “nigalya-ponya” which means “bamboo eater“. Possibly derived from a Nepali word referring to the ball of the foot-perhaps a keen observation of how this bear eats bamboo with an adapted wrist bone that functions as an opposable thumb and sixth digit.

Other writers believe that “panda” came from wah , the Nepali name for the red panda (Ailurus fulgens), and originating from the childlike sound that this species sometimes makes.

Probably the word panda was borrowed into English from French, but no conclusive explanation of the origin of the word panda has been found.

Ailuropoda melanoleuca – How the Panda got his scientific name

The giant panda as it appears in the formal scientific description of the species, published in the early 1870s. Illustration: H Milne-Edwards and A Milne-Edwards. 1868-1874. Public domain, edited.

The modern name giant panda can be attributed to the French missionary Armand Pere David (1826-1900), who lived in China from 1862 to 1874. Preaching in Beijing and Shanghai, David was also a correspondent researcher of the National Museum of France. A natural historian, David has found 68 new species of birds, over one hundred species of insects, and many mammal species-including the Milu deer, golden monkey and the giant pandas- in various places of China.

In March 1869, David came to the catholic church in Dengchigou of Muping (now Banshan County) of Sichuan and became the fourth preaching priest there. The Dengchigou Catholic Church was one of the earliest churches secretly built by the Cathedral Church of France in Sichuan.

In his journal, David writes:

“On March 11, 1869, when I was on my way back to the Church, I was invited to have a rest in a Mr. Li’s home. In his home, I saw the panda’s skin. It’s big and beautiful colored black and white. The skin was quite peculiar. Li told me that I would see this animal very soon, for his hunters were going to hunt this animal-

it seemed that a new species in the science domain will be found”

“After leaving for 10 days, the hunters were back today. They brought a young whitebear to me. It was caught alive, but was killed only to bring it back more easily.”

David pitied the death of the young panda cub, and he wrote on:

“they sold the young whitebear to me at a very high price. The body of the whitebear was all white except that the legs, the ears and the places around its two eyes are black. It has the same skin color as a grown-up bear that I have seen before. I believe it to be a new species, not only because of its skin color, but also because of the hair beneath its feet and other characteristics.”

David sent this specimen of whitebear to Melne Edwards, the director of the Natural Museum of Paris, who studied the skin and skeleton of the animal and published a paper in 1870, announcing

“in terms of external features, it is really very close to bears; but its skeleton and teeth are apparently different from bears – actually very close to raccoons. It must be a new species, and I name it Ailuropoda.”

Paying tribute to David’s contribution, Edwards named the scientific name of the Giant panda as Ailuropoda melanoleuca David, which has been used until now.

The first giant panda specimen collected by David is still kept in the Natural Museum of Paris.

Pandas are a well-known symbol of Chinese culture and have various symbolic meanings worldwide:

The Han Dynasty

Jade objects, pottery, lacquer work, bronze equipment, sculptures, and bronze mirrors of the Han Dynasty of 206 BC to 22 AD, are often decorated with bears. That’s because people of that period worshiped the bear and honored him by putting his image on many objects.

The Bear Emperor

The bear wasn’t always the preferred totem of China. Emperors prior to the Han Dynasty used other animals symbolically. In the Shang Dynasty, the totem was a bird; the Shu emperor used the silkworm as his personal totem. The dragon was also imbued with significance. But it wasn’t until the Yellow Emperor built his capital at Xinzheng, a place with some bears, that he became known as the Bear Emperor.

Feng Shui

Fêng-shui, “the art of adapting the residence of the living and the dead so as to co-operate and harmonize with the local currents of the cosmic breath”, a doctrine which had its root in ancestor-worship, has exercised an enormous influence on Chinese thought and life from the earliest times, and especially from those of Chu Hsi and other philosophers of the Sung dynasty.

It is the Chinese art of harmonizing humans with their environments. According to this philosophy, a bear represents masculine energies, and placing a figure of a bear in the home, – particularly the main entrance,- helps to protect the house and its inhabitants.

Also, placing a bear’s image in the part of the home where children might reside helps parents to give birth to strong, healthy babies.

Yin and the Yang

Yin and Yang symbol. Public domain.

The Chinese ascribe much importance to the Yin and the Yang, two opposing forces of the universe that are present in all aspects of nature. A common representation of the Yin and the Yang is a circle, half black and half white, depicting the dichotomy of the two colors but the interconnected nature of the two forces.

The Giant Panda is thought to be a physical manifestation of the Yin and the Yang, as its body is both black and white, the two colors standing in stark contrast to one another on the animals pelt. The placid nature of the panda is a demonstration of how the Yin and the Yang, when perfectly balanced, contribute to harmony and peace.

Pandemonium

The word pandemonium was coined in 1936 to describe the reception a panda received when it was first shown in the West. The first panda to be seen in Europe and America was a cub named Su-Lin – “something very cute“– , brought from Sichuan province by a rich socialite named Ruth Harkness.

With extensive media coverage the cub was first displayed at the Chicago Zoo, drawing a crowd of 54000, a number that has yet to be repeated. While cameras clicked away, Harkness, dressed in a fur with a cigarette dangling from her lips, fed the panda with a baby bottle. He eventually became a hot attraction in Chicago’s Brookfield Zoo, where it died a year later.

WWF

It was in London, however, that a stateless bear’s sudden popularity made the panda the poster child for all things endangered. In 1957, Chi-chi, originally slated for sale to a U.S. Zoo, found herself homeless when the United States, which had no formal relations with China, refused the panda entrance.

But the London Zoo made a successful bid for Chi-chi in 1958, and she quickly became the zoo’s star attraction. As it happened, London was also the home of the newly formed World Wildlife Fund (WWF), which still lacked a logo.

Deciding that there was no better candidate than the lovable Chi-chi, the WWF chose the panda as its official logo in 1961, and the black-and-white bamboo-munching creature has been an international symbol of wildlife conservation ever since.

Pandas are the face of animal rights but in the popular imagination, they are not really bears at all – they are cartoon characters, a creation of movies like Kungfu Panda, the fuzzy panda hats sold at tourist attractions around China, and even Fuwa the Panda, one of the five mascots of the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

While the dragon has historically served as China’s national emblem, the giant panda has served as an emblem for the country too in recent decades. Its image appears on a large number of modern Chinese commemorative gold, silver and platinum coins.

The giant panda made it even on red and gold cigarette packets, the brand is called GOLDEN PANDA.

ETHNOMEDICINE:

Panda- USE:

During the Ming Dynasty, the panda was described as having great medicinal value. In Compendium of Materia Medica (Bencao Gangmu), a record of traditional Chinese medicine, the famous pharmacist Li Shizhen of Ming Dynasty recorded:

“bedding made of panda fur can prevent coldness and wetness, as well as pestilence and vice; oil of panda can penetrate the skin to cure tubers; and its urine, drunk together with water, can dissolve metal things eaten by mistake.”

In addition to using its urine to dissolve metal, rubbing the mo’s feces on a knife would make it sharp enough to cut through gemstones.

*It is also said that the creature’s fat was good for treating swellings, but very hard to keep because it could seep through containers made of copper, iron, or pottery; so it could only be stored in a stone container.

*Sleeping on a mattress made from the pelt of a mo warded off diseases caused by bad air and dampness; in fact, illustrations of the mo were said to have the same effect… for this reason, an illustration of a mo was often put on window shutters during the Tang dynasty [618 C.E – 906 C.E].

In his 1993 book The Last Panda, U.S. biologist and naturalist George B. Schaller explained how Chinese used to hunt pandas for their pelts because it was believed that sleeping on panda fur could ward off ghosts and help regulate a woman’s menstrual cycle.

*Traditionally, eating a bear’s gallbladder and bile was said to have medicinal powers. Chinese today still consume the bile extracted from moon bears, sun bears, and brown bears; the substance is believed to be therapeutic and is an ingredient in traditional Chinese medicine.

Yet bile extraction is a painful and invasive process, and some bear bile farms keep bears locked in tiny cages for years at a time. Bear farming, which uses some 10,000 Asiatic black bears to harvest medicinal bile and which generates almost $1 billion a year.

Though humans apparently ate panda in prehistoric times, contemporary Chinese have little taste for the animal. There is an oft-cited saying that Chinese people will “eat anything with four legs except the table” — including braised camel hump, monkey brains, and shark’s fin on the occasional (luxe) Chinese menu.

The liberal Chinese palate often extends to animals kept as pets, with dogs, rabbits, and even cats sometimes meeting their end as a soup or spicy dish. But panda banquets are unheard of. They are certainly too precious to eat, but their flavor might also have kept them off the dinner table.

Schaller details the trial of 26-year-old farmer Leng Zhizhong, who unintentionally snared a radio-collared panda in the western province of Sichuan in January 1983 while trying to trap Musk deer and wild pigs. In a bid to dispose of the evidence, he chopped up the bear and stir-fried its meat with turnips.

It was a dish so inedible he ended up feeding it to his pigs. (He also gave some to his sister.) The court sentenced Leng to two years in prison.

~ ○ ~

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- A picture of 1600 pandas (maked in Thailand by the World Wide Fund for Nature) exposed in Boulogne-Billancourt (France), Saturday, 27th March 2010 on the occasion of Earth Hour.

- Merritt Christine. Panda Bears and the Moon Goddess: Myths and Legends of China. 2017. https://web.archive.org/web/20241202235722/http://www.g-casa.com/conferences/macau/pdf_paper/Merritt-Moon%20Goddess.pdf

- A baby panda at the Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding in Sichuan, China, took a shine to one of the workers this week.

- A study of Giant Panda’s name history.http://www.kepu.net.cn/english/giantpanda/giantpanda_know/200409230029.html

- A Tibetan Legend. Pandas International

- Harper Donald. Journal Article. THE CULTURAL HISTORY OF THE GIANT PANDA (“AILUROPODA MELANOLEUCA”) IN EARLY CHINA. Vol. 35/36 (2012–2013). https://web.archive.org/web/20231013160750/https://www.jstor.org/stable/24392405.

- Historical Records in Ancient China. http://www.kepu.net.cn/english/giantpanda/giantpanda_know/200409230028.html

- Immage: https://sites.google.com/site/bamboo257/pandas-in-chinese-culture

- Levy Debra. Symbolic Meanings of the Bear in Chinese Culture.http://animals.mom.me/symbolic-meanings-bear-chinese-culture-8866.html

- Mo, Jiaotu, Nietie, & An: Metal-Eaters of China. http://monstersherethere.com/monster/mo-jiaotu-nietie-metal-eaters-china

- Newborn giant panda triplets rest in an incubator at the Chimelong Safari Park in Guangzhou. Photograph: Chimelong Safari Park/Xinhua Press/Corbis/Corbis. Recherches pour servir à l’histoire naturelle des mammifères. Paris :G. Masson,1868-1874.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/39564366

- Olesen Alexa. Chinese People Used to Think Pandas Were Monsters. 2014.https://foreignpolicy.com/2014/10/23/chinese-people-used-to-think-pandas-were-monsters/

- Panda in Chinese Culture. http://chinesehoroscop-e.com/astrology/panda-in-chinese-culture.php

- PANDAS. http://factsanddetails.com/china/cat10/sub68/item379.html

- Panda Tibetan Folklore Panda Tibetan Folklore. The Panda:Tibetan Folklore. https://wildernessrambles.wordpress.com/2015/01/04/the-panda-tibetan-folklore/

- Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuaries – Wolong, Mt Siguniang and Jiajin Mountains. UNESCO.

- Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuaries. Wikipedia.

- The story of the panda. http://pandajaan.tripod.com/Panda%20Story.htm

- Western naming of Giant Panda in recent times http://www.kepu.net.cn/english/giantpanda/giantpanda_know/200409230030.html

Keep exploring: