Orang-utans, being uncannily like humans and highly intelligent, at the same time as being large and extremely strong, have long been a source of major fascination for the peoples of Sumatra and Borneo who share their forests with them. Discover Myths and legends of the Orang-Utan in Indonesia.

In this Article

Francine Neago

“Have you seen the Orang-utans of Indonesia?”,

she asked, carefully biting into the home made shrimp cracker. We are in a humble Warung in Banda Aceh- north Sumatra sharing the table with a lady with silver hair, very pale skin and only a few teethes left. “I will visit them at the Gunung Leuser National Park ”, I answered. Her eyes started to spark as I asked her about Orang-utans 🦧.

“They are so human, so intelligent”

, she started. The lady I am sitting with is one of the world’s leading primatologists who spent her life in the jungles of Sumatra, the nearly 90-year-old Francine Neagois also a campaigner for Orang-utan conservation and the founder of a wildlife sanctuary “Noah and his Ark” in Indonesia.

She has fascinating stories to tell about her red friends:

“Orang-utans are extremely intelligent creatures who clearly have the ability to reason and think. I trained them to learn to communicate with us. Orang-utans are large, but in general gentle. Large males can be aggressive, but for the most part they keep to themselves. They are uniquely arboreal – living their lives quietly up in the trees feeding… and only descending to the forest floor when they need. Were it not for the occasional squealing of a baby or calling out of a big male, you would hardly even know they were there. They don’t bother anyone.

It is traditionally believed, that the Orang-utans could talk but chose not to, as a sign of their high intelligence afraid that they might be enslaved and put to work.”

Orangutans communicate with a variety of vocals and sounds. Male orangutans will make long calls, both to attract females and to promote themselves to other males.

Both sexes will try to intimidate the opposite sex with a series of low-frequency sounds known collectively as the “rolling call”. When feeling uncomfortable, orangutans will produce a “squeak kiss”, which is done by sucking air through pursed lips. Baby orangutans make soft shrieks when they are stressed. When building nests, orangutans will make popping sounds or blowing with their tongues. The mother orangutan will make a throat chattering sound to maintain contact with her child. Geographic variation within call types (accents) has been reported for Orang-utans and other primate species:

Her eyes got sad, her hands shake a little, as she tells me about the enslavement, she works with Orang-utans that have been used as sex slaves or kept as pets in small cages, she knows about the fires in Kalimantan, where the palm-oil lobby just burns the people of the forest because they clear their territory or shoot them as they like to eat the fruits of the palm.

On Noahs Ark’s homepage she writes:

“I have spent the past forty years of my life studying and caring for the animals-especially the orang-utans. Anyone who has lived closely with them can only admire and love them. I have dedicated my life to their protection.”

Ketambe: Gunung Leuser National Park

The leeches, surprisingly, weren’t too bad at our three days jungle track. We thought they did not get me until I pulled up my pants leg and found both my socks stained in blood. Our guide shrugged. “That means they are already full and fell off. Not to worry – we use them for medicinal healing.” So I didn’t worry, changed the bloody socks, and scratched my itchy leech bites. But we are here for the Orangutans:

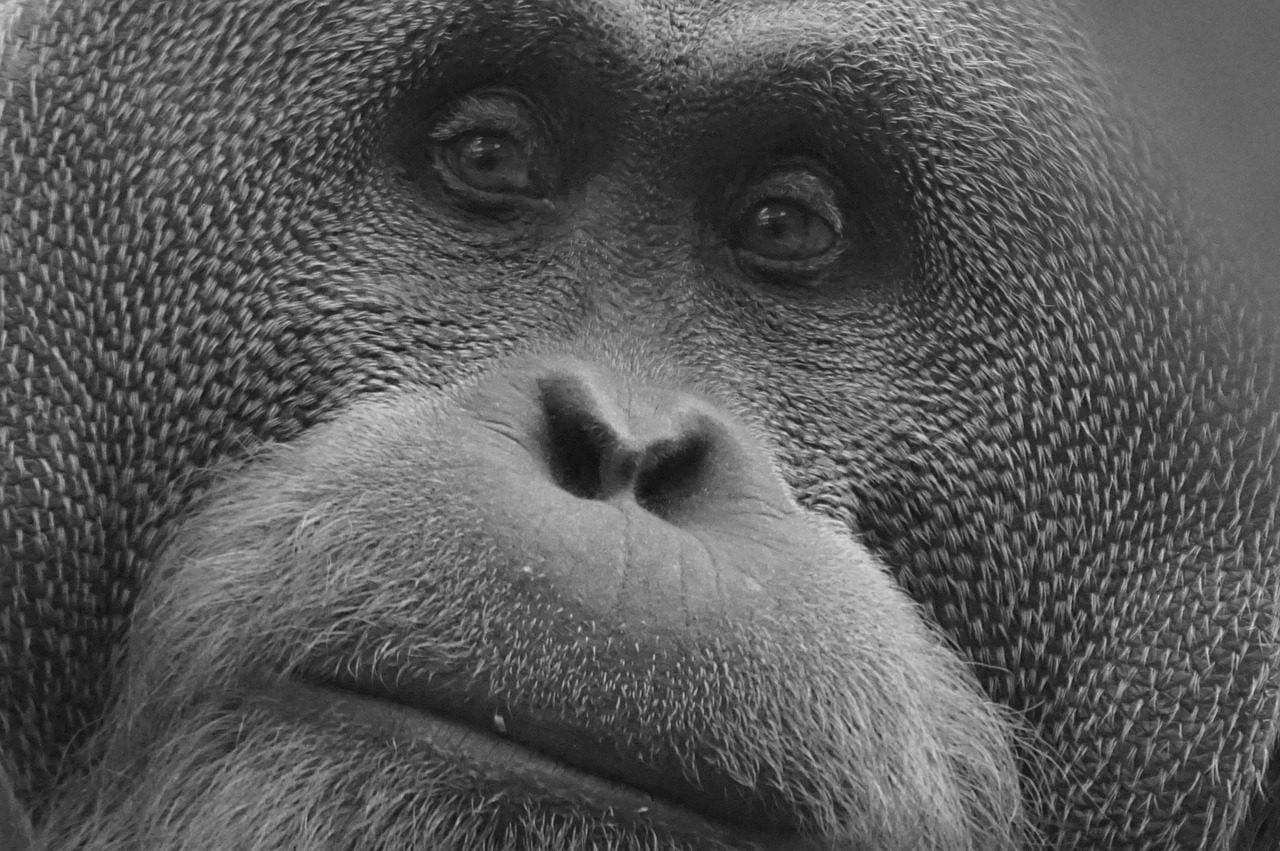

Watching an Orang-utan, you’ll swear they’re just like us. Their similarity to us is uncanny. They share 97 per cent of our DNA, and have expressions and gestures that resemble our own. In a heavy rain storm, they will pluck off a large leaf to use it as an umbrella.

It was stunning to watch a mature male with full face flange and throat sac, eating honey and calmly reaching from tree to tree with his long arms and legs. Orang-utans do travel extremely slowly and deliberately through the trees. They never rush, never jump or leap, and all of their movements are careful and cautious. Holding on with at least two limbs almost all of the time, and three or four if possible, to spread their load between different supports, using their feet as well as their hands to grasp branches and lianas.

Apart from leeches,wild Orangutans we have observed a wealth of other wild life including a big group of Thomas Leaf monkeys, black gibbons and a Rhinoceros horn bill.

Back in Musliadi’s Leuser Guesthouse we got to witness how a sleeping nest is build:

After the foundation, she bend smaller, leafy branches onto the foundation; this serves the purpose of and is termed as the “mattress”. Then, she braid the tips of branches into the mattress, to increase the stability of the nest and forms the final process of nest building. Orang-utans may add additional features such as “pillows”, “blankets”, “roofs” and “bunk-beds” to their nest.

I couldn’t stop watching her with her two babies making her nest in the evening, just in the trees over our veranda. In the morning the little family woke us, because of the tree branches that would fall on the roof, perfect- I took my googles and watched them having breakfast.

They express emotions just like we do: joy, fear, anger, surprise… it’s all there. Baby Orang-utans cry when they’re hungry, whimper and smile at their mothers.

Primates should be given their own form of human rights. Orang-utans are mystical animals and the primates might, indeed, end up as mystical animals in the absence of conservation efforts.

ETYMOLOGY: Orang Utan

Orang-Utan comes from Orang hutan in Malay and Indonesian languages, meaning

- forest man,

- people of the forest,

- reasonable being of the woods or

- old person of the forest.

From orang “man” + utan, hutan “forest, woods, wild.” The sense of ‘orang’ is one of intelligence, reverence and respect, the local people came into close contact with Orang-utans, they understood that these creatures were a sort of ‘person’.

But this is not the local name for the animal, but one adopted from Dutch, orang-outang (1631), by early travellers. It is possible that the word originally was used by town-dwellers on Java to describe forest people of the Sunda Islands and that Europeans misunderstood it to mean the ape.

The name in Malay is not applied to the creature, but there is evidence that it was used so in 17c. [OED]

Within its own range, the red ape is known by a variety of names, such as

- mawas among the Malays and in northern Sumatra,

- maias among the Bidayuh, Dayak and Ibans,

- kahui by the Muruts, and

- kogiu or kisau by the Kadazans and Orang Sungai.

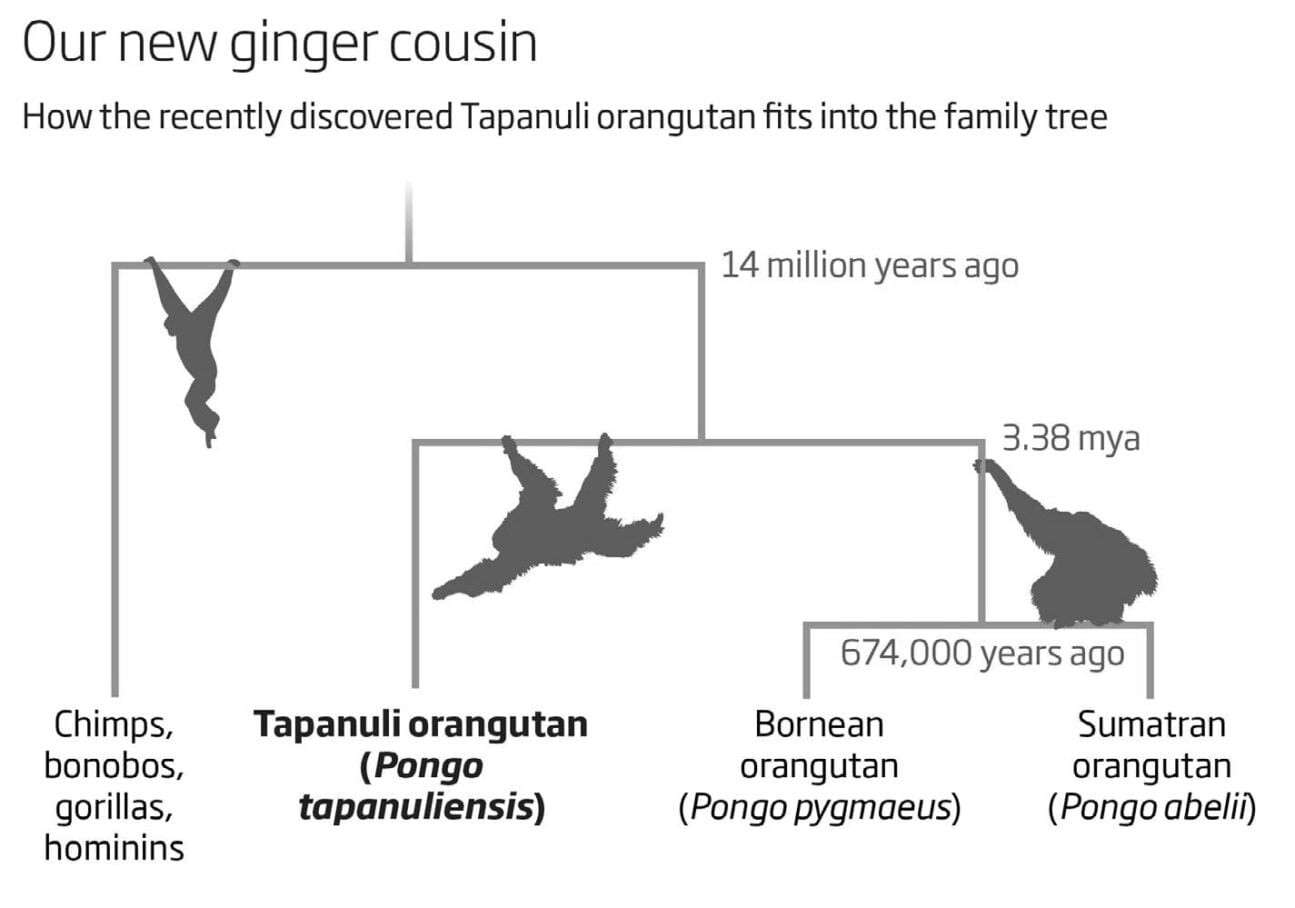

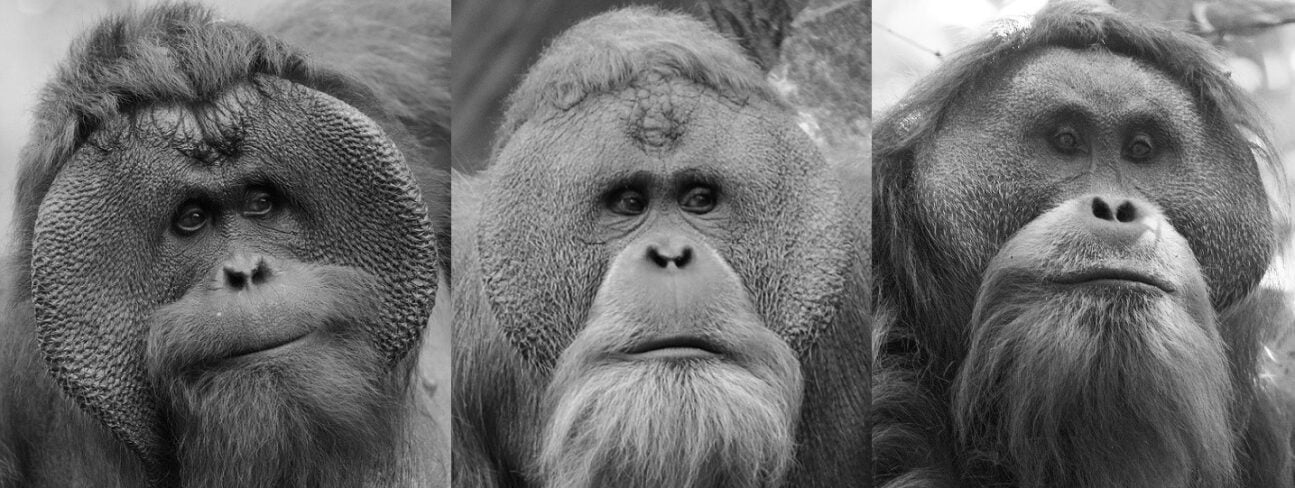

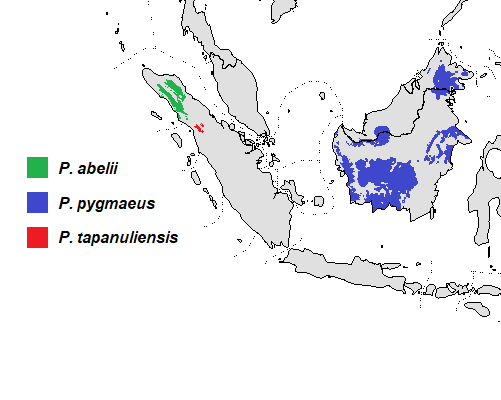

For years, researchers have recognized two species of orangutan living in Indonesia: the Bornean Orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) and the Sumatran Orangutan (P. Abelii), named after the British surgeon and naturalist Clarke Abel who, in 1825, first described

“an ourang-outang of remarkable height”

found on the island of Sumatra.

In the late 1930s there were reports of a population of orangutans in Tapanuli, in the Batang Toru area, south of the range of Sumatran orangutans, but the claims were never fully investigated. The Tapanuli population was only rediscovered for science in 1997 by Erik Meijaard at the Australian National University in Canberra. His study reveals that the orangutan lineage first split around 3.38 million years ago, when the Tapanuli orangutans split off from the rest. That main population would then split in Sumatran and Bornean orangutans much later, around 674,000 years ago.

MYTHS AND LEGENDS OF THE ORANG-UTAN IN INDONESIA

Centuries ago, the first people of Borneo and Sumatra, recognized the Orang-utans close affinity to human beings. Knowing a great deal about Orang-utans, for instance, because they share the forests with them and coexist mutually with the nature surrounding them. The peoples who share their forests with Orang-utans have developed stories, beliefs and legends about these red apes.

THE DAYAK PEOPLE

The Dayaks came to Borneo from the Malay Peninsula and Sumatra in waves starting some 4000 years ago. This was part of the great island-hopping expansion of the Austronesians from their original base in Taiwan.

In Borneo the people believes Orang-utans to be superior than human beings. Some believe that humans descended from Orang-utans, and others that humans turn into Orang-utans when they die. According to a legend, Orang-utans were bad humans punished by the gods for their evil deeds. They were cast out into the forest and covered with red hair.

The people know Orang-utans to be fruit lovers, for instance, appearing where fruits are abundant and fading into the forest when they are not. They can describe how Orang-utans seek honey, reaching into a nest with one hand while the other hand covers their eyes against the angry swarm of stinging bees. They speak with admiration of their subtlety, telling how an Orang-utan can pull a tree over by a single leaf, playing the forces so finely that the leaf does not snap off. And they recount with great enjoyment the antics of Orang-utans who became village “pets”. Those that have met Orang-utans directly speak with awe and fear of their strength, invulnerability, and ferocity if attacked.

Under traditional systems of land tenure among the Dayaks, every longhouse community in Borneo claims an extensive tract of community land. Within these territories, individual families have rights to the lands they clear for farming [areas known as kebun or ‘gardens’]; these rights are inherited. The ‘gardens’ are maintained in a system of cultivation followed by a fallow period when secondary vegetation reclaims the site. Community land extends beyond the cultivated areas and includes swamp and virgin forests that are conserved for the collecting of wild produce and hunting.

Hunting and eating the Orang-Utan

Hunting of Orang-utan was widespread amongst the Dayak peoples, generally using a blowpipe and poison. The apes were considered to be a prized and delicious food item and also a medicine to ensure sexual potency. Infant Orang-utans were kept as pets in longhouses or sold.

But Orang-utans were also hunted for religious reasons, as they possessed a soul and this soul substance, was considered higher than that of humans. Dayak head-hunters saw Orang-utan heads as powerful symbols, in their ceremonies.

Under some traditional systems, certain families or clans were restricted from eating Orang-utan meat; this may have spared the species from extinction in a number of areas.

Dayak taboos surrounding Orang-utans

- Dayaks took care not to offend them, look straight at their faces, or laugh at orang-utans.

- Pregnant Kayan women were forbidden to look at them.

- The Iban Dayaks of Sarawak would not eat their meat.

- Dayak tales all portray orang-utans as very close to humans, as powerful persons worthy of respect.

It was believed that they would kidnap women and take them to the forest, never to be seen again.

Amale orang-utan abducts a comely woman. He carried her up to his leafy nest high in the forest canopy. Although terrified at first, she finds her captor kind and gentle.

After the woman has an infant, she longs to see her parents and family. The child, however, is half orang-utan and half human. So she fashions a rope out of vines and orang-utan hair she has collected from the nest and, flees. The orang-utan pursues her.

During the chase, the woman drops her infant. In his rage, the father tears the baby in half, keeping the surviving orang-utan for himself. The woman retrieves the human half and leaves the forest, returning to her village.

DAYAK Creation Myths

A widespread Dayak creation myth tells that God’s first attempt to breathe life into humans gave birth to Orang-utans. Only on the second try, did humans come into being.

This myth captures an essential truth and an evolutionary fact, that orang-utans appeared on this planet long before modern humans did. Although the Dayak myth seems parallels to the modern knowledge of human evolution, there are several variants of this creation myth.

Dixon tells:

Thus the Dyaks of the Baram and Rejang district in Borneo say that after the two birds, Iri and Ringgon, had formed the earth, plants, and animals they decided to create man. At first, they made him of clay, but when he was dried he could neither speak nor move, which provoked them, and they ran at him angrily; so frightened was he that he fell backward and broke all to pieces. The next man they made was of hard wood, but he, also, was utterly stupid, and absolutely good for nothing. Then the two birds searched carefully for a good material, and eventually selected the wood of the tree known as Kumpong, which has a strong fibre and exudes a quantity of deep red sap, whenever it is cut. Out of this tree they fashioned a man and a woman, and were so well pleased with this achievement that they rested for a long while, and admired their handiwork.

Then they decided to continue creating more men; they returned to the Kumpong tree, but they had entirely forgotten their original pattern, and how they executed it, and they were therefore able only to make very inferior creatures, which became the ancestors of the Maias (the Orang Utan) and monkeys.”

Variant of the Dyak creation Myth:

At first, they made him of clay, but when he was dried he could neither speak nor move, which provoked them, and they ran at him angrily; so frightened was he that he fell backward and broke all to pieces. The next man they made was of wood, but he, also, was utterly stupid, and good for nothing. Then the two birds searched carefully for a good material, and eventually selected the wood of the Kumpong tree, which has a strong fiber and exudes a quantity of deep red sap. Out of this tree they fashioned a man and a woman, and were so pleased with this achievement that they rested for a long while. Then they decided to continue creating more men from the Kumpong tree, but had forgotten how. They made inferior creatures, which became the ancestors of the Maias [Orang Utan] and monkeys.”

Another variant:

Two birdlike beings created all life on earth, and one day they created man and woman. This was a great accomplishment so to celebrate, they feasted late into the night. The next day they tried to make more humans, but not feeling so well after the night’s revels, they messed up the recipe and created Orang-utans instead.

THE IBAN PEOPLE

The Iban, now among the most populous people in parts of Sarawak and West Kalimantan, are relatively recent arrivals from Sumatra. They invaded Borneo along the Kapuas River in West Kalimantan during the 15th century. Resident Dayak groups were absorbed or displaced as the Iban spread. The Iban called the Orang-utan “forest cousins.”

Legend: How the Ibans learned to use ginger as a medicine

Long ago, while looking for game deep in the jungle, an Iban hunter saw a pair of Orang-utans on top of a tall tree called perawan.

The female Orang-utan was giving birth while the male was crushing the roots of some plants.

When the Iban hunter passed under the tree where the Orang-utans were nesting, some chunks of roots fell on him.

“What are these things?” he asked.

He took a sniff but could not tell what the roots were.

The hunter was not put off, however. He took the roots back to his longhouse and planted them. And in time, the roots yielded what is known ginger.

When the hunter’s wife gave birth, he applied the ginger on her body — like he saw how the orang-utan was doing.

According to the collectors of this legend, Kebong Manggum of Rumah David Ujan and Ng Sepaya (Ulu Engkari), that was how the Ibans learned about the medicinal values of ginger and the knowledge was passed down and is still being used to these days.

Another variant of how the Ibans learned to use ginger, tells us:

Long ago, the story goes, humans used to give birth by opening up an expectant mother with a machete. Then one day, a woman was about to give birth in the forest when a female Orang-utan saw her. The Orang-utan carried the woman up into her tree-top nest, and showed her how to give birth properly.

Ulu Engkari and Ulu Menyang

Iban communities in the two areas — Ulu Engkari and Ulu Menyang — are different, their folklore is distinct from other Iban communities in Sarawak. While the Ibans from the other areas may regard Orang-utans, especially those encroaching onto their gardens, as food, their counterparts treat the primates as relatives and forefathers. This is one of the reasons a significant number of the great apes is still found in the two areas.

According to the folktales, the Iban communities let their women give birth naturally. Before this, husbands used to cut open the wombs of their wives to deliver newborns. So for every new life, a mother had to pay with her life.

There are also tales of Orang-utans changing into men and women and marry the local Iban people. It is, thus, not surprising the Iban communities here regard Orang-utans as relatives or ancestors, the communities believe that whenever their ancestors passed away, they would reincarnate as Orang-utans and come back to visit them.

Ulu Engkari and Ulu Menyang taboos surrounding orang-utans

So unlike the Iban communities in other areas, those in Ulu Engkari and Ulu Menyang have for centuries lived side by side with the orang-utans.

- It is taboo for them to hurt or hunt orang-utans.

- Traditionally, the Iban communities believe, killing orang-utans would have repercussions. Hunters who killed Orang-utans would bring ill not only upon themselves but also the whole longhouse. They will die one after another from accidents or will be wiped out by some diseases in an instance.

- Tales are sometimes told of wild Orang-utans attacking or raping humans, and of humans and Orang-utans marrying and producing half-human, half-ape children.

- In Borneo, if a woman has an ugly baby, this might be ascribed to her having looked at an Orang-utan during her pregnancy or immediately after the child was born.

- For some people, it is considered bad luck to look into the face of an Orang-utan, and laughing at one can bring misfortune to the whole longhouse community.

IBAN Myths and legends of the Orang-Utan in Indonesia

On the other hand, in some stories the orang-utan is considered highly benevolent. Tales are told of how Orang-utans saved an ancestor or other relative from a disaster.

Others say that Orang-utans are reincarnations of respected members of the community, and therefore allow them to feed in their fruit gardens undisturbed. This and similar beliefs protect the Orang-utan from being hunted or otherwise harmed by Ibans in this areas. The peoples animistic believe, says that after death an ancestor becomes a member of a particular species Ifual and, in this form, can help his or her living descendants.

This belief continues in some tribes today; one study found the orang-utan to be a tua species among seven households in the Batang Ai region of Sarawak,” though it was permissible to hunt the apes to obtain a head on special occasions. “

Some Iban groups regarded the Orang-utan as being a representative of their war god. Related to this belief was the custom of the Kelabit and Kayan peoples that involved rubbing dirt and ape hair into the breast of a newborn child, to prevent it being stolen by an ape. The skin and hair of Orang-utans have been used until the present for war cloaks, jackets, and caps, and to decorate the handles of swords.

Some stories suggest they made no clear distinction between humans and apes. Indeed, traditionally prepared trophies of human skulls have been found mixed with Orang- utan skulls.

“Many stories tell of attacks, and rapes, of women by male Orang-utans, and (occasionallyl of men” by female orang-utans. In these stories, women were often kept as the Orang-utan’s lover or bride; in some accounts inter-breeding occurs.

Other stories describe the great strength of Orang-utans in fights with pythons, crocodiles, or bears.

The Kenyah and Kayan peoples are unable to look straight into the eyes of an Orang-utan in case they offend it, but they will still hunt and eat it.”

MODERN STORIES – The power of folklore

Informal institutions surrounding Orang-utans in West Kalimantan include a range of beliefs, taboos and stories, from ancient traditions to more recent anecdotes.

There are stories old and new of Orang-utans serving as protectors of humans. Iban Dayaks are told by their grandparents and great-grandparents of the assistance given by Orang-utans during the ethnic conflict in the 1900s. More recent stories from the 1980s tell of an Orang-utan who protected a boy from a crocodile attack, and another who rescued a woman from a clouded leopard.

Such stories generate a sense of respect for Orang-utans, encouraging kind treatment and protection. Traditions and anecdotes like these are powerful because they encourage or discourage certain types of behavior. Linda Yuliani, from the Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry, says:

“Degraded ecosystems cause degraded traditions, especially in cases where traditions are related to nature […]

By raising up traditions, ecosystems also benefit.”

Media is filled with stories about the plight of Indonesia’s increasingly endangered Orang-utans, who are threatened with poaching and the rapid destruction of their natural habitats due to deforestation. In the wetlands of Indonesian Borneo, local people also tell many stories about the Orang hutan whose environment they share. In many such tales, the great apes are allies, helping humans by teaching them the secrets of the forest, or aiding them against their shared enemies.

The mythic power of these stories starkly affects perceptions about Orang-utans in a way that no environmental regulation or poaching law ever could. Take, for example, this story collected by researchers doing a case study on how folktales affect local people’s perceptions of the animal:

An Anecdote from Kalimantan

AMalay man said that, once, while logging in a protected area, he witnessed a colleague shoot an Orang-utan from a tree.

As the animal fell, they saw that it was a female orang-utan holding her young. Before she died, the man said, the mother Orang-utan took a big leaf and expelled her breast milk onto it for her baby to feed on.

“He was really sad when he witnessed that the mother was so close to her baby. He cried when he told the story,” researcher Linda Yuliani, lead researcher on the study, said.

The story is retold with a surreal moral ending – the colleague who shot the Orang-utan had a pregnant wife at home, and when she gave birth the child was said to be covered in hair, just like an Orang-utan.

The anecdote resulted from a case study conducted within and around the Danau Sentarum wetlands of West Kalimantan, which found that traditions and stories among local people are playing a role in the conservation of Orang-utans and the forests they depend on. The study shows that Orang-utan numbers remain highest in areas not only with good habitat condition, but also where informal institutions are strongest.

“There is a strong relationship between traditional knowledge systems and ecosystem condition,” says Yuliani. “And this has implications for the conservation of wildlife.”

In some areas, informal institutions, such as customary rules, may have greater impact than formal legislation. Yuliani says that while very few respondents in the case study could identify laws or sanctions relating to Orang-utan conservation, the majority knew of and respected traditional beliefs and taboos.

Habitat loss

In the mainstream narrative, local people are often blamed for hunting, poaching and killing Orang-utans, as well as competing against them for resources in protected forest areas. Over the past decade, the Bornean Orang-utan has gone from ‘Endangered’ to ‘Critically Endangered’ on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. In the Danau Sentarum National Park and its surrounds, a 2010 review found the number of Orang-utan nests in the area had dropped by 55% in less than a decade, from 264 nests in 2001 to only 147 in 2010.

Orang-utans are protected by law in Indonesia, but their habitat in many cases is not. Land-use planning laws that favor large-scale development projects have led to widespread deforestation and land conversion for mining, timber and oil palm plantations. Fire, illegal logging, and the effects of climate change have further destroyed the available habitat for Orang-utans, while poaching, hunting and illegal trade continues under weak law enforcement.

Yuliani’s research shows that Orang-utans remain better protected in areas where traditional beliefs and taboos are practiced, highlighting local people as allies in conservation efforts.

Historical accounts of Orang-Utans by Western explorers

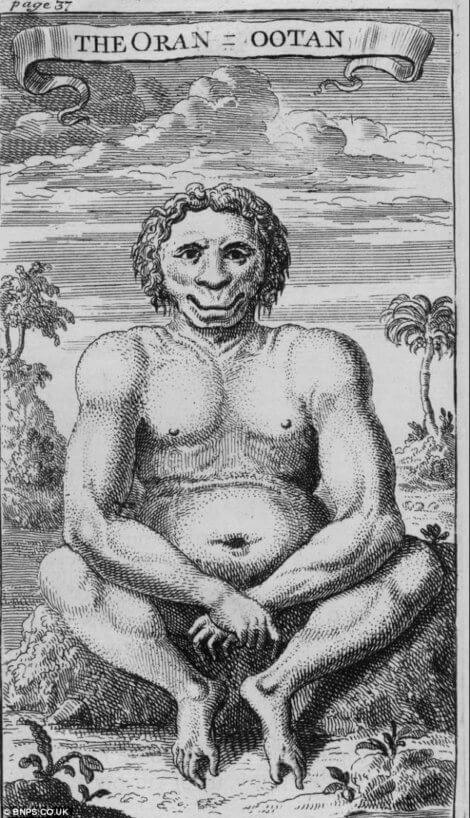

Western explorers were fascinated by the first glimpses and descriptions of Orang-utans — although with some of the very earliest descriptions, it was unclear if they were describing Orang-utans, or some of the local people whom they met.[sic!]

Jacob de Bondt

So the Dutch doctor Jacob de Bondt or Bontius is credited with the first ever written description of wild Orang-utans in 1642. He noted that the Malays told him the orangutan could speak, but chose not “so he wouldn’t be forced to work”.

Daniel Beeckman

In 1712, Captain Daniel Beeckman gave an authentic description of orang-utans in southern Borneo, and wrote:

“The Monkeys, Apes and Baboons are of many different Sorts and Shapes; but the most remarkable are those they call Oran-ootans, which in their language signifies Men of the Woods: these grow to be up to six Foot high; they walk upright, have longer arms than Men, tolerable good Faces (handsomer I am sure than some Hottentots [sic!] that I have seen), large Teeth, no Tails nor Hair, but on those parts where it grows on human bodies.”

This portrait of a female in Sumatra who seemed to have an idea of modesty, covering herself with her hand on the appearance of men with whom she was not acquainted has led people to question whether this was indeed an orang- utan or an unusually hairy woman! [sic!]

Captain Beeckman, like the European immigrants who came up with the name, was referring to the Khoikhoi people of southwestern Africa.

“Hottentot” is now understood as an offensive racial term.

The first ever depiction of an Orang-utang seen in the West has been uncovered in a 1718 first edition of explorer Daniel Beeckman’s “A Voyage to the and from the Island of Borneo”.

Alfred Russel Wallace

By the time naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace undertook his famous explorations of the Malay Archipelago in the mid-1850s, written descriptions of Orang-utans were becoming much more accurate. For example, Wallace said:

“The Orang-utan is known to inhabit Sumatra and Borneo, and there is every reason to believe that it is confined to these two great islands… The long and powerful arms are of the greatest use to the animal, enabling it to climb easily to the loftiest trees, to seize fruits and young leaves from slender boughs which will not bear its weight, and to gather leaves and branches with which to form its nest… Each mais (orang-utan) is said to make a fresh one for itself every night.”

Robert W. Shelford

Even so, much of the Orang-utans’ behavior was to remain unknown for many more years. In 1916, Robert W. Shelford commented that

“considering its size, the Maias (orang-utan) is remarkably inconspicuous in its natural surroundings. Until men can acquire arboreal habits it seems likely that the domestic arrangements of the ape will remain undiscovered.”

Indeed, virtually all of the descriptions of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries were written by people whose main intent was to collect specimens for museums, and their writings were more about catching and killing the animals than about their behavior. Wallace himself describes killing 17 Orang-utans in his expedition of 1855 and, twenty years later, William Hornaday collected an incredible 43 animals from western Sarawak for American natural history museums. Such killings for museums peppered the writings of naturalists right through to the 1930s.

It was not until from the 1970s onward that the west has obtained a more accurate picture of the natural behavior and ecology of Orang-utans.

~ ○ ~

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350364896_Witnessing_the_Unseen_Extinction_Spirits_and_Anthropological_Responsibility/fulltext/605be5d8299bf173676869cc/Witnessing-the-Unseen-Extinction-Spirits-and-Anthropological-Responsibility.pdf THANK YOU

- Bennett Elizabeth. The Natural History of Endangered Ape. Natural History Publications and CL Chan. Galdikas Birute M.F., Nancy Briggs. 1999.

- Caldecott Julian, Miles Lera. World Atlas of Great Apes and their Conservation

- Catriona Croft-Cusworth for Forest News

- Cheng Lian. Keeping alive folktales of orang-utans [email protected]

- Dixon, Roland B. Oceanic Mythology. 1916.

- Orangutan cultures. Universität Zürich Department of Anthropology Research Orangutan network. https://www.aim.uzh.ch/de/research/orangutannetwork/culturelist.html

- Mus Ketambe guest house

- Russon Anne. 2004 and 2005. https://phys.org/news/2016-04-history-orang-utans-human-culture.html#jC

- Stories to save the orangutans. Version of this article. on Forest News, the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR). For more information on this topic, please contact at [email protected]. This research forms part of the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry.

- White Miles H. Lyn. Language and the Orang-utan: The Old ‘Person’ of the Forest, in Paola Cavalieri & Peter Singer (eds.), The Great Ape Project. 1993.

- Woodward Aylin. There is a third species of orangutan and somehow nobody noticed. 2017. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2152276-there-is-a-third-species-of-orangutan-and-somehow-nobody-noticed/

‘

Keep exploring: