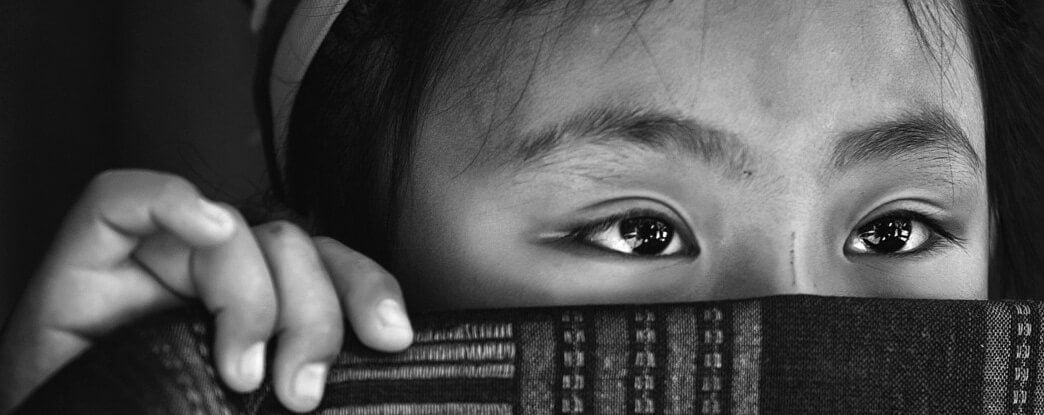

Discover Myths, History and Folklore of RICE in Malaysia, goddesses, harvest festivals and rituals.

Although rice only became a major economic crop in Malaysia in the 20th century, rice husks have been found in a cave in Gua Sireh in Sarawak, and has been dated from 2300 BC showing that people were growing rice there more than 4000 years ago.

In this Article

In Malaysia, the rice found at Gua Cha in Kelantan dates to the 11th century. However rice was grown for primarily for personal use, before rice was the staple food of all the immigrants, Chinese and Indian, Sumatran and Siamese, who poured into the Malay states through the nineteenth century.

Rice fueled the growth of tin mines and of pepper and sugar plantations, and fed the great trading ports and military posts of Malacca, Singapore, and Penang, as it did the new towns that sprang up in the hinterland as the economy prospered under enterprising Malay rulers.

It is believed that there are several goddesses related to rice, they gave rice to humans and taught them how to grow it. Religious use of rice takes place in Malaysia, India, China, Thailand, Indonesia and Sri Lanka. In Asia, the rice spirit is female and often a mother figure. Like in this myth from Borneo- Malaysia:

Bambarazon – The Goddess of Mercy

In ancient times man had no rice with which to still the pangs of hunger, but had to live from wild fruits and flesh of wild animals. It is true that the rice plants were there, but at this time the ears were empty, and naturally no food could be obtained from them.

One day, Bambarazon, the Goddess of Mercy, saw how difficult men’s lives were and how they were always hungry. Her compassionate heart was touched and she decided to help them. One evening she secretly slipped down the fields and pressed her breasts with one hand until her milks flowed into the ears of rice.

She squeezed and squeezed until there was no more milk left, but all the ears were not filled; so she pressed once more with all her might, and a mixture of blood and milk came out.

Now man had rice to eat. The white grains are those that were made from Bambarazon’s milk, and the red ones are those that were formed out of the mixture of her milk and blood.

From generation and to the present day, every Dusun or Kadazan celebrates the “Modsurung“, which is known today as the Harvest Festival, in memory of the great Goddess of Mercy. She is also important in Taoism.

RUNGUS PEOPLE & Bambarazon – The Rice Spirits

Bambarazon is also the term used by the Rungus, to identify spirits associated with rice cultivation. They live in scattered longhouses in Kudat District in the northern corner of Sabah- Malaysia.

Rice is the traditional and the most important crop for the Rungus. They believe that rice was first brought to them by the rice spirits, Bambarazon, in the remote past. Bambarazon take care of rice so the Rungus praise them by sacrificing fowls and pigs in order to receive good harvests. If the Rungus neglect the ceremonies, they will expect poor harvest.

According to this myth, rice was brought to the Rungus people by a dog. So that every year when the Rungus harvest their rice, a small portion of rice is first given to the dog of the house-hold. This myth is similar to the Chinese rice myth.

Once, as a man from a Rungus village was walking along a pass, he noticed a dog walking along the trail near him. The man noticed that when the dog wagged its tail, seeds flew from it and were spread around the roadside. But, because the seeds were unfamiliar to him, the man thought nothing of it and continued on his way home.

Later, the man had a dream. In the dream a person appeared and asked him,

“Why didn’t you take this rice seed? Why don’t you sow it? It is a gift to you.”

When the man awoke, he remembered the seeds the dog had spread and returned to the spot. He collected the seeds and sowed them. From that time on, the Rungus have cultivated rice regularly.

The culture hero that brings agricultural know-how of rice cultivation is a woman.

Once, a Rungus village man had twin children, a son, and a daughter. As the years went by and the twins reached the age of fifteen, they found that they felt such great love for each other that they did not wish to look for other marriage partners.

Their father was so deeply worried about the matter that he asked the village head and other people of his village for a solution. The problem of the twins was discussed and argued for three months.

Eventually, the villagers decided that the twins must immigrate to a new land. So the village head, the father, and his twins began their search for an uninhabited land. Finally, they found a suitable place. The village head and the father left some food for the twins and returned home.

After five days, the twins had eaten all the food, and they had begun to starve and grew weak. They lay still for five more days, and soon they knew they were dying.

One morning when the twins woke up, there beside them were two plates of rice and vegetables. They were very surprised, and asked each other,

“Who has put these plates here? We do not know who has offered the food to us but we would like to have it again.” They ate the food and thus did not die that day. The next day the same thing happened, then the next day, and the next day after that. But still they did not know the source of the food.

At last, after another week, they discovered an old woman bringing the food. And when she was discovered, she said to them, “After you have finished eating, come to my house.” When they had finished eating, they followed the old woman.

The house of the old woman was a great distance away and took a very long time to reach. Finally, they arrived at a big tree. The woman said, “This is my house. You can sleep here”

The twins could not see any house, but they slept on the spot.

Each morning and evening, the old woman offered food to the twins. This continued for a week, then one day the old woman said,

“I will give you a parang (machete) and other equipment for cultivation. You have to reclaim the land.”

The old woman left the twins with the equipment and the rice and maize seeds. As she was leaving, she added, “Do not burn this big tree because it is my house.” The twins then slashed the jungle foliage and burned it. They then sowed the rice and maize. They also built a house near the rice field.

One day, the old woman informed them,

‘‘When the crops have ripened, you can harvest them. Until the harvest, I will bring food to you everyday.”

Time passed, and the rice and maize were harvested. After the harvest, the old woman disappeared. The twins had baby twins. The children grew up and married each other and had baby twins. This marriage of twins continued for many generations.

The following myth describes the relationship between the Rungus (rice cultivators) and Bambarazon (rice spirits). Bambarazon, who live in a distant land beyond the sea, are the keepers and protectors of rice. So if people do not pay respect to them, they will take revenge on the farmers by bringing them poor harvests.

Once, a Rungus man travelled for a long period of time and eventually came to a sea. He there obtained a small sail-boat and continued his journey until he arrived at a distant shore where he came upon a large red house in which many red men lived.

One of the red men asked him, “Who are you?” ‘‘I am a Rungus and I am on a journey,” he replied.

“Ordinarily, I would eat you, but I will let you go this time. However, you must leave immediately,”

warned the red man. The Rungus man left and went to the next house.

This house was just as large as the previous one and again the same thing happened. In all, he visited seven houses, but none welcomed him. So, he had to continue his journey.

Finally, he arrived at another house and asked if he could stay there.

The people in the house welcomed him and offered him food and accommodation. He said to the people, “I am a Rungus. Who are you?” The people replied, “We are Bambarazon.” Carefully, he looked at Bambarazon, and noticed they had body burns. The Rungus man asked them, “What happened to you Bambarazon?” And Bambarazon replied, “There was a man who burned the Sulap (rice storage hut) before he finished the rice harvest. This is why we have body burns.”

He stayed with Bambarazon for seven days and they gave him the directions to his homeland. On his way home, he re-crossed the sea. The crossing went well although he did not use the sail.

When he arrived home, he met a farmer who complained of his long run of poor harvests. He asked the farmer for detail of his methods, and the farmer replied that he had burned his Sulap before he finished the harvest. He remembered Bambarazon and their burns. Thus he advised the farmer to sacrifice some chickens to Bambarazon. The harvests began to get better each year.

Then one night, the farmer had a dream and heard voices saying:

“You have pleased us Bambarazon. But for your final sacrifice, you must have the Magahau ceremony, sacrificing fowls and pigs to Minamangun.”

After he celebrated the Magahau ceremony, he continued to receive good harvests.

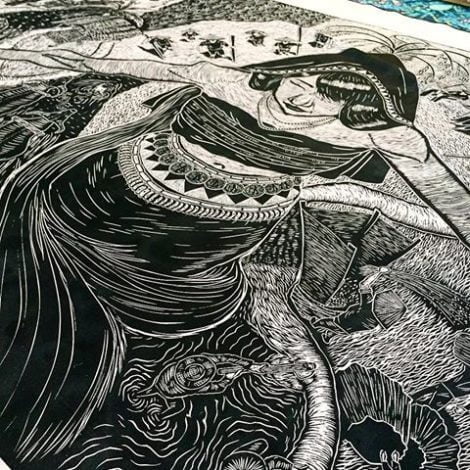

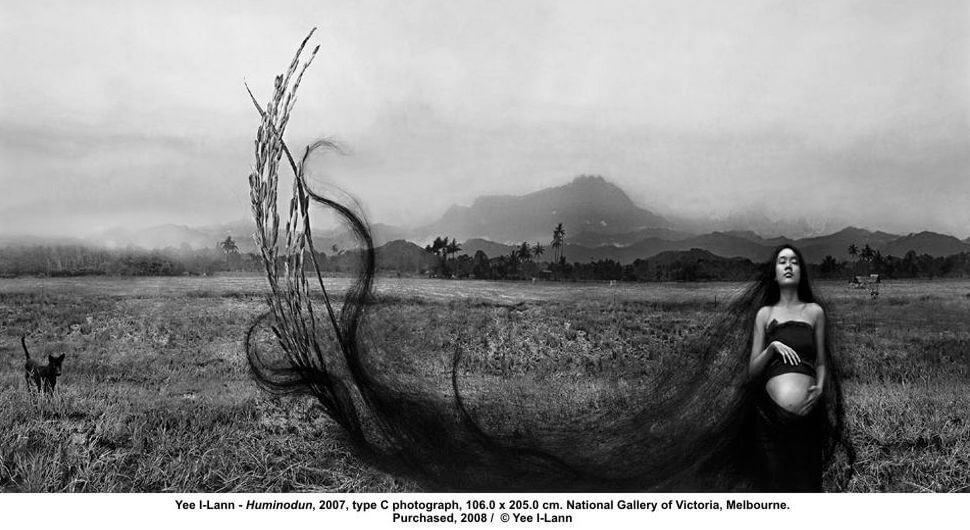

The legend of Huminodun

Unduk Ngadau owes its origin from a part of Kadazandusun genesis story, which pertains to sacrifice of “Huminodun” – Kinoingan’s only begotten daughter.

The term “Unduk ” or “Tunduk” literally means the shoot of a plant, which, in it most tangible description, signifies youth and progressiveness. Likewise, in its literal meaning, “Ngadau” or “Tadau” means the sun, which connotes the total beauty of the heart, mind and body of an ideal Kadazandusun woman. In essence therefore the “Unduk Ngadau” is an event of selecting from among the Kadazandusun beauties, one who would resemble the ascribed personality of “Huminodun”.

Along, long time ago, the staple food of Kinoingan and his people was a type of grain called “Huvong“. One day, there was no huvong left to plant, nor other grains left for food. Kinoingan was so worried and felt very sorry for his people sufferings. It was said that Kinoingan sacrificed Huminodun, the only child to Kinoingan and Suminundu. She was the most beautiful maiden in her time, truly anyone who gaze at her lovely countenance would be transfixed and fall in love with her. She was also kind hearted and blessed with wisdom beyond her years.

Huminodun was willing to be a sacrifice and be an offering to the great earth so that there will be seeds once again for planting and there will be food for the people. Kinoingan was deeply saddened, but seeing that there was nothing else he could do to dissuade her, Kinoingan went ahead and cleared the land for planting. Through his supernatural powers, he was able to clear such a large area over many hills without any difficulty. When the time came for planting, Huminodun was brought to the cleared plot. As she was leaving, one cold hear the pitiful wails of great sadness from Suminundu, her mother. It was not at all easy for Huminodun to leave her mother and likewise her mother letting her only child go. The young men who had fallen in love with Huminodun could not let her go either. Indeed, they too cried and begged her to change her mid. However, there was nothing anyone could do, Huminodun had decided that her father’s people came before her.

When she arrived at the cleared plot, she turned to her father and said: “Father, you will see that my body will give rise to all sorts of edible plants for the people. My flesh will give rise to rice; my head, the coconut; my bones, tapioca; my toes, ginger; my teeth, maize; my knees, yams and others parts of my body to a variety of edible plants. This way never again will our people grow hungry to the point of dying.”

“However,” Huminodun continued, “Do follow these instructions of mine for it will guarantee us a bountiful harvest. When you have strewn parts of my body all over this clearings, do not come and see me for seven days and seven nights. When the padi has ripened, and it is time for harvest, do not start the harvest without doing this; take seven stalks of rice (padi) and tie them to one end of a spliced bamboo stick and them, plant this stick at the center of the rice (padi) field.

Only after this may you begin your harvesting activities. Later, place this bamboo stick with the seven rice (padi) stalks in the rice (padi) storage container (tangkob) when you bring it home after the harvest. For your first day harvest, do keep them in a big jar (kakanan). And, Father, do not give away your first year’s harvest because the grains may become bad. You can only give away your harvest to others in the second year.”

That is why to this day, the Kadazandusun people do not give away their first years harvest.

Kinoingan agreed to follow all her instructions. So it was that when Kinoingan sacrificed Huminodun, the whole world turned dark and there was awesome thunder and lightning.

That year, the people had never seen such a harvest. It was plentiful. Kinoingan had done as Huminudun instructed He also kept away the first day’s harvest in the kakanan and harvested the first seven stalks of rice from the rice plot. The seven stalks of rice represented Bambaazon, the spirit of the padi or rice.

As for the rice in the jar, the kakanan, on the seventh day a beautiful maiden miraculously stood up out of the big jar. She was referred to as Undul Ngadau, the spirit of Huminodun. It was said that this Unduk Ngadau was the one who instructed the first Bobohizan or Kadazandusun priestess in her prayers.

Therefore to this day, the Kadazandusun people have included the Unduk Ngadau Pageant as a grand part of their Kaamatan Festivals. It is a manifestation to the deep sense of respect and admiration that the people have for the legendary Huminodun. It is a sacred title ascribed to Huminodun, to her absolute obedience to Kinoingam, so much so as to be a willing sacrifice for the sake of the father’s creation. “Unduk Ngadau” then is a commemorative term in praise of Huminodun’s eternal youth and the total beauty of her heart, mind and body.

Semangat Padi – The Rice Soul

In Malaysia, it was traditionally believed that rice, or paddy, was animated by a soul- the rice soul semangat padi. The semangat- soul is a generalized idea or notion of a vital principle which enlivens and animates objects and living things in this world. It is the extra vitality or vigor complementing the life principle – nyawa in living beings or the intrinsic power embodied in magical objects and is variously conceived as a diminutive but exact counterpart of it’s own embodiment- or as appearing in the form of an insect, a bird, or an animal.

The rice soul is encountered in this Myth:

In olden times, rice was not harvested from the fields. Every morning a grain would appear in the house of the farmer and find it’s way into the rice pot. The housewife would normally cook the rice grain without even opening the pot cover, which was taboo- pantang. By the afternoon the pot would be full of rice ready for consumption.

One morning, the housewife planned to leave the house for her farm and therefore she warned her children never to open the rice pot during her absence. Once the mother had gone one of the younger children grew curious and tried to open the pot. Unbeknownst to her elder sister she peeped into the pot and saw a little girl inside. Suddenly the little girl disappeared leaving only a small grain of rice. Her elder sister was very angry and scolded her severely.

When their mother returned, she found that there was no rice in the pot. She knew that it had been opened and scolded her younger daughter for disobeying her instructions and breaking the taboo. But it was no good crying over split milk, and from that day on wards they had to work very hard to plant the rice, harvest it, and then carry home all the grains.

As the paddy has a good spirit and therefore semangat padi (the soul of paddy) must be respected. The most obvious example of anthropomorphism in this context is the existence of semangat padi. As mentioned by Frazer:

“if Europe has its Wheat-mother and its Barley-mother, America has its Maize-mother and the East Indies their rice-mother.”

Taking the Malays and Dyaks as representing the East Indies, he commented on what he has termed “the soul of a plant”:

Now the whole of the ritual which the Malays and Dyaks observe in connexion with the rice is founded on the simple conception of the rice as animated by a soul like that which these people attribute to mankind. They explain the phenomena of reproduction, growth, decay, and death in the rice on the same principles on which they explain the corresponding phenomena in human beings.”

Asmah Haji Omar further elucidated the importance of this spirit. According to her:

“The padi plant is treated with more “reverence” than any other plant. The padi, inclusive of the grains, is said to have a soul or semangat which has to be “cared for” all the time. Any crudity in the handling of the padi plants or grains may drive the semangat away. This explains the succession of rituals that the padi farmer has to conduct and taboos that he has to observe from the moment the seeds are sown to the time the padi grains are stored away”.

Rituals and the RICE SOUL

There are several names used to address the rice soul in invocations and incantations during various rites, especially at first harvest – menua ulung.

The soul was adored like a new born baby and lovingly addressed as

- the nine-month baby- anak sembilan bulan,

- sunray princess- anak maharaja cahaya, or

- the crystal princess- si dang gemala

This human treatment of rice reflects the inherent Malay attitude of treating all humanity with utmost respect and kindness.

The human attributes of the rice soul became the focus of complex rituals and elaborate ceremonies with a strong emotional content which built up to almost cultic veneration and adoration in the various rites throughout the cycle of rice cultivation.

From the first step of selecting rice seeds, to the process of growing, transplanting and weeding and up to the time of the first harvest, the final storage and the first tasting of the crop, a series of rituals was carried out to express the need for a good harvest and the survival of the community from hunger ad starvation.

The souls were entreated and invoked to remain with the rice and not to abandon its rice-seed embodiment or the community.

The Pawang, as mediator between humans and supernatural beings- would tenderly cradle a handful of seeds at the beginning of the sowing ceremony or during the cutting of the first few stalks at the first harvest. The Pawang’s entire attitude would be one of appeasement and tender care of the soul against human violation or destruction by malignant spirits. The first few stalks were cut with a small palm-size reaping knife to avoid hurting the tender soul or inflicting violence on the ears of rice.

Female Pawang, or house wifes, would normally invite the soul, believed to be embodied in a selection of the best of the newly reaped seeds to return home with them. The first seven ears of rice to be reaped were swaddled and tenderly places in a specially made basket, the cradle of the rice soul. The basket would then be carefully kept in the rice store for next year’s cultivation.

As Zainal Kling, writes:

This rituals suggest a strong notion of the rites of fertility, the concept of mother earth and rebirth in the mother seeds ibu benith – the receptacle of the child like rice soul.

THE IBAN PEOPLE

Rice Rituals

The Iban people enact the Gawai Batu to ensure that the rice they plant will provide a huge harvest. The ceremony for the planting of the rice starts by a shaman or a lumambang who recites the Mantra menanam padi:

Oooh haa…oooh haa…oooh haa…

I pray while I wave a chicken

I want to plant good rice

Because today we want to sow the seeds

Good seed the beautiful god

We entreat the gods with incantations

So that they will give us a good yield

A proper harvest

These are offering plates, five of them to worship

We call on the gods To praise the god of the soil

So that we may be pleased

With a very good harvest

Please come, Petara Datuk, Petara

Nenek, Petara Ayah, Petara Ibu

Come and partake of our meal together with us

With the palm wine, with the rice wine we have set ready for you

THE DAYAK PEOPLE

Rice Rituals

The Dayaks in Sarawak consist of many tribes such as the Iban, Bidayuh, Kenyah, Penan, and OrangUlu most of whom are Christians but who also often are still animists and worship rice. They continue to strongly believe in invisible beings and supernatural powers. Therefore, the Iban organize all kinds of celebrations- gawai, such as Gawai Kenyalang, Gawai Antu, Gawai Batu, and Gawai Pakutiang while the Bidayuh enact their Gawai Padior Tanah, all of them requiring the role of a shaman known as a lumambang to mediate with invisible beings, spirits, and supernatural powers.

The Gawai Padi

Haron Daud about the ritual:

The celebration, started with the erection of a platform and the division of the place into three parts. One part was for the musical instruments including some gongs, a gendang, and a kenong. One part was for the ceiling to which were attached the fangs and the tail of a pig as well as food for the offering including palm wine and pork picked in brine.

On the last part, they built a cradle for the ahli bulih (group of chosen women) where they could swing and sing their bulih songs. In front of the committee, a small cabin with offerings was made as a place for the spirits to meditate and on the second day, the leg of a pig that was killed the night before was hung there. The ritual was opened and enacted by the chairman of the shamans and some retainers and started at midnight. The chairman opened the ceremony by reciting a mantra to call the evil spirits so that they would descend to partake of the meals that were set ready for them so that they would not feel disturbed.

The next morning the participants walked in procession to the river to enact the ritual to call the rice spirits. They believed that the rice spirits descent from the hill following the course of the river. The shaman recited various mantras to call them while he was accompanied by the gong and by some women who

were shaking water in a bowl.

The rice spirits arrived with some balls of hair and some non- husked rice, which they put into the water in the bowl.

The moment the spirits arrived, the gong and gendang stopped playing and the women who shook the water caught the spirits and each put one in their respective bags to take them home. They needed to protect the rice spirits in order to ensure a yearly good rice harvest.

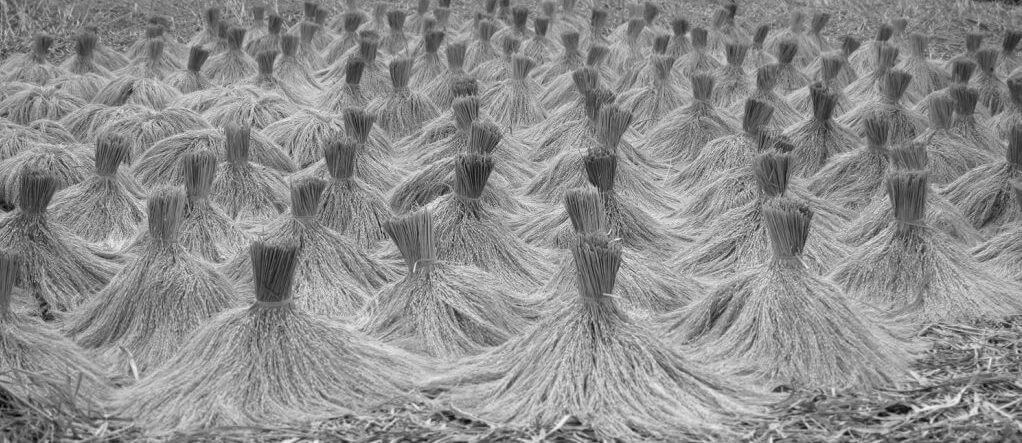

Harvest Festivals around Malaysia

The Harvest festival celebrated in Malaysia by the Kadazan of Sabah each May with thanksgiving dedicated to the rice gods. Agricultural shows, exhibitions, cultural programs, buffalo races, and other traditional games are held. There is much merrymaking and feasting with rice wine flowing freely throughout the festivities.

The Rice Harvest in Malaysia or Gawai Dayak is usually held on the second day of June.

At harvest time the whole of the Malaysian community work together in the rice fields, gathering the stalks by hand. Traditional Malaysians harvest rice with a special knife whose carved handle is said to appease the Semangat or rice spirit.

In the month of May, Saba Hans celebrate The Kadazan Harvest Festival. The Kadazan Harvest Festival is known locally as ‘Tadau Ka’amatan’. According to their beliefs, the spirit of the paddy plant is said to be part of the Kinoingan – also known as the Bambaazon, who is revered as the creator, a source of life and existence. The rice spirit Bambaazon is therefore revered in the rice plant, the rice grain and the cooked rice. Many believe that “Without rice, there is no life”.

During the festival, Sabah natives wear their traditional costumes and enjoy a festive atmosphere which stretches from daybreak till dawn. ‘Tapai’ or home-made rice wine is served as the specialty for the day. Sabahans are greeted with a special greeting for the harvest festival known as ‘Kopivosian Tadau Ka’amatan’ or ‘Happy Harvest Festival’.

In Sarawak the rice harvest is celebrated every year on the June 2nd, sometimes the 1st. When the last of the grain has been collected, villagers gather at midnight, in slant-roofed longhouses perched on tall stilts, deep in the jungle. They first offer a thanksgiving for the harvest and invoke blessings for the next harvest; the people then eat a protracted banquet. A most essential part of the meal is the rice wine, also offered to the gods in the miring ceremony.

The Kadazandusun and Murut people have been celebrating Pesta Keamatan or Harvest Festival in their own unique way, paying homage to the rice spirits called Bambarayon to show their gratitude for their bountiful harvest. Merrymaking takes place in various villages and districts which host their own celebrations throughout the month of May.

The finale of the celebrations is the two-day state festival held at chosen places such as Hongkod Koisaan in Penampang on the 30th and 31st of May.

Highlights of the festival include the Magavau, a traditional thanksgiving ceremony by the Bobohizan or High Priestess, the Unduk Ngadau or traditional Harvest Festival Queen, cultural dances and much merrymaking.

Traditional beliefs have it that Bambarayon can be threatened by pests, natural disasters, or even by the carelessness of the farmers themselves. To applause Bambarayon, Magavau which means “to recover what has been lost, by whatever means,” must be performed.

Lead by the high priestesses, the Bobohizan and their assistants perform a ritual symbolizing the search for the stray Bambarayon to be safely brought ‘home’.

Moving in a single file, close to one another, the Bobohizan and their assistants enter the ‘spirit’ world in search of Bamabarayon. Every time a stray Bambarayon is located, piercing screams or pangkis is heard, expressing joy at the find, thus ensuring that they have another good harvest.

After paying homage to the rice spirit, a merrymaking feast is celebrated.

Those present are traditionally served with chicken porridge, eggs and meat only that it is a belief that green vegetables are a sign of disrespect to the guests of Bambarayon and only the best tapai or rice wine is served. Keaamatan celebrations are filled with rituals, music, songs and dances which are pure expression of Sabah cultural joy and merriment.

As technology changes agriculture, creating a system where harvest comes closer to a guarantee, traditions and mythology, such as this varied rice stories and Rice- Ceremonies have changed. The ceremonious aspect of rice farming is no longer as prevalent.

The extents of Myths, History and Folklore of RICE in Asia are hardly to be seized here, there is still much more to discover.

~ ○ ~

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- THE MOTHER GODDESS OF FERTILITY AND RICE

- TIMELINE: The story of rice

- MALAYSIA: Proverbs and wise sayings in relation to RICE Beras or Nasi

- CHINA: Proverbs and wise sayings in relation to RICE 稻

- CHINA: On the origin of Rice 稻 – Myths, History and Folklore

- THAILAND: Mae Posop- Myths, History and Folklore of RICE

- THAILAND: Proverbs and wise sayings in relation to RICE K̄ĥāw

- INDIA: Proverbs and wise sayings in relation to RICE Chaaval

- INDIA: Myths, History and Folklore of RICE

- INDIA: RICE dishes Khichri, Byriani, Kheer, Dosa &Idlly

- INDONESIA: Myths, History and Folklore of RICE Nasi

- BALI- INDONESIA: Myths, History and Folklore of RICE Nasi

- NDONESIA: FOLK TALES ON RICE

- INDIA: FOLK TALES ON RICE

- CHINA : FOLK TALES ON RICE 稻

- Daud Haron. Oral traditions in Malaysia- A discussion of shamanism. Wacana, Vol. 12 No. 1 . 2010.

- Frazer James George. The golden bough: A study in magic and religion. 1922.

- Harvest Festivals from Around the World. Malaysian Harvest Festival. http://www.harvestfestivals.net/malaysianfestivals.htm

- Low Kok On. BELIEF IN BAMBARAYON (PADDY SPIRITS) AMONG THE KADAZANDUSUN OF NORTH BORNEO. Borneo Research Journal. 2012.

- Lim Kim Hui. Budi as the Malay mind: A philosophical study of Malay ways of reasoning and emotion in peribahasa. 2003.

- Rice as a Superfood. Encyclopedia of Food and Culture – Encyclopedia.com. http://www.encyclopedia.com/food/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/rice-superfood

- Shimomoto Yutaka. Myths and Ritual for Rice Spirits Bambarazon among the Rungus. http://asianethnology.org/downloads/ae/pdf/a339.pdf

- The Origin of Rice. https://salammalamjumaat.blogspot.com/2016/05/the-origin-of-rice.html

- Zainal Kling. The soul of a people, in: Rice-land civilizations. The UNESCO Courier: a window open on the world. Vol.:XXXVII, 12. 1984.

- Image: https://web.archive.org/web/20180315121057/http://www.therakyatpost.com:80/news/2015/05/30/gawai-dayak-brings-families-closer-together/

- http://www.sarawakreport.org/campaign/radio-free-sarawak-crony-commerce-is-killing-sarawaks-rice/

Keep exploring: