There are many origin myths and much folklore about rice. In China goddesses, gods, and sacred animals gave rice to humans and taught them how to grow it.

Religious use of rice takes place in China, India, Thailand, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Malaysia. Discover Myths, History and Folklore of RICE in China, one of the oldest rice cultures.

In this Article

For more than half of humanity, rice is life. Every third person on earth eats rice every day in one form or another. Rice is grown on about 250 million farms in 112 countries. It is the grain that has shaped the history, culture, diet and economy of billions of people of Asia.

Throughout the past years we spend in Asia, rice has been omnipresent in our live and pivotal to all aspects of peoples life. In history rice was fostering societal and community development, waging war or seeking peace, creating wealth or enduring poverty, enjoying good health or surviving famine or providing a foundation for spiritual worship of deities.

On the mythological origin of rice 稻

Myths, History and Folklore of RICE in China

In Chinese culture, many of the stories that have been told regarding characters and events which have been written or told of the distant past have a double tradition: one which presents a more historical and one which presents a more mythological version. This is also true in many of the accounts related to the acquisition of rice and agriculture in China.

Goddess of rice Guan Yin

AChinese story says that although rice has always existed, there was a time that the ears of the rice plants were not filled. Observing that humans were near starvation, the Goddess Guan Yin took pity on them.

She went secretly to the rice fields and squeezed her breasts so that milk flowed into the ears of the rice plants. To complete her task, she pressed harder and a mixture of blood and milk flowed into the plants.

This is the reason today we have both white and red rice.

The name Guan Yin also spelled Guan Yim, Kuan Yim, Kwan Im, or Kuan Yin, is a short form for Kuan-shi Yin, meaning “Observing the Sounds (or Cries) of the (human) World”.

Rice is the blood of the Goddess

Agoddess visited all points of the compass besieged by hunger until in one place she found a herb and undressed in front of it. From the plant’s bud trickled a few drops of milk and the goddess gave a few drops of blood. From this arose rice: white inside and red outside.

Another Rice Goddess

We been told another version, of a benevolent goddess in silk robes whose gown accidentally picked up stray rice grains, which she dropped from the heavens to humans below.

The Rice Goddess and Buddha

Another Chinese legend tells that in a distant time, the Goddess of Rice competed with Buddha to demonstrate her power. At a celebration held by Buddha, the Goddess of Rice suddenly disappeared and the people had no rice to eat and were hungry and desperate. Aware of this, Buddha decided to find her and convince her to return.

后土 Houtu

Houtu (also spelled Hou Tu) the Deity of Earth, is an almighty goddess in the pantheon. People offer her sacrifices and pray to her for harvest, rain, children, health, wealth, safety when boating in the Yellow River, and the tide when a boat is stranded. In local legends, Houtu often is depicted as a kind, wise, and powerful goddess.

One story says she helped Yu solve his problem in channeling the flood to the sea. When Yu channeled the Yellow River, he wrongly opened it toward the west. Because the rocks and stones in the west were extremely hard, his work progressed very slowly. As he worked, Yu felt worried because the flood season would soon come.

When Houtu the Sacred Mother heard this news, she drew a map of the Yellow River and thought over possible Solutions. Then she had an idea. She ordered one of her divine birds to tell Yu that he should open the channel eastward. Yu took her suggestion and finally succeeded in directing the floodwater toward the east sea. The place where he wrongly dredged later received the name “River Wrongly Opened.”

At another time, Houtu visited Yu and was sympathetic about his bad living conditions. She used her great power and in minutes made a huge cave for Yu and his helpers to live in. To thank Houtu, Yu suggested naming this cave “the Sacred Mother ‘s Cave.” But Houtu was modest; she thought Yu brought more benefits to the world, so she insisted the cave be named “King Yu’s Cave.”

Furthermore, Houtu learned that Yu was unable to supply enough food for his workers, so she and her daughter cooked a large pot of rice gruel every day for the hardworking laborers. No matter how much the laborers took, the pot of gruel was never emptied. The place where Houtu and her daughter cooked was later called “Rice Gruel Temple.”

Lü Tung-pin – One of the eight immortals brings RICE

There are various versions of the legend of Lü Tung-pin (also spelled Lu Dongbin)

One of these tells, that in order to fulfill his promise made to Chung-li to do what he could to aid in the work of converting his fellow-creatures to the true doctrine, he went to Yüch Yang in the guise of an oil-seller, intending to immortalize all those who did not ask for additional weight to the quantity of oil purchased.

During a whole year he met only selfish and extortionate customers, with the exception of one old lady who alone did not ask for more than was her due.

So he went to her house, and seeing a well in the courtyard threw a few grains of rice into it. The water miraculously turned into wine, from the sale of wine and rice the dame amassed great wealth.

CHINESE MYTHS OF RICE BEING A GIFT OF ANIMALS

A Bird brings rice

It is said that the ancestors of the Miao people of Sichuan, did not have the necessary seed to sow their fields. They set a green bird free which then flew up to the rice granary of the heaven god and returned with the heavenly rice seed.

A Dog brings rice

China had been visited by an especially severe period of floods. When the land had finally drained, people came down from the hills where they had taken refuge, only to discover that all the plants had been destroyed and there was little to eat. They survived through hunting, but it was very difficult, because animals were scarce.

One day the people saw a dog coming across a field, and hanging on the dog’s tail were bunches of long, yellow seeds. The people planted these seeds, rice grew, and hunger disappeared.

According to the myths of various ethnic groups, a dog provided humans with the first grain seeds enabling the seasonal cycle of planting, harvesting, and replanting staple agricultural products by saving some of the seed grains to replant, thus explaining the origin of domesticated cereal crops. This myth is common to the Buyi, Gelao, Hani, Miao, Shui, Tibetan, Tujia, and Zhuang peoples.

Asimilar legend, from the Han Chinese of Sichuan, speaks of the aftermath of a great flood. The survivors of this flood were without crops and in a state of desperation. They noticed a dog crawling out of the flooded fields, and from the rice seed that clung to the dog’s tail they were able to begin rice cultivation. Their feelings of gratitude to this dog led them to give it a portion of the first meal after the harvest.

Aversion of this myth collected from ethnic Tibetan people in Sichuan tells that in ancient times grain was tall and bountiful, but that rather than being duly grateful for the plenty that people even used it for personal hygiene after defecation, which so angered the God of Heaven that he came down to earth to reclaim it all.

However, a dog grasped his pant leg, piteously crying, and so moving God of Heaven to leave a few seeds from each type of grain with the dog, thus providing the seed stock of today’s crops. Thus it is said that because humans owe their possession of grain seed stocks to a dog, people should share some of their food with them.

Another myth, of the Miao people, recounts the time of the distantly remote era when dogs had nine tails, until a dog went to steal grains from heaven, and lost eight of its tails to the weapons of the heavenly guards while making its escape, but bringing back grain seeds stuck onto its surviving tail. According to this, when Miao people hold their harvest celebration, the dogs are the first to be fed.

The Zhuang and Gelao peoples have a similar myth explaining why it is that the ripe heads of grain stalks are curly, bushy, and bent – just so as is the tail of a dog.

Throughout China today, tradition holds that “the precious things are not pearls and jade but the five grains“, of which rice is first.

五穀 Wǔ Gǔ – The Five Grains

Are typically translated as the “Five Cereals“, and less often as the “Five Sacred Grains” or “Crops“.

五穀 Wǔ Gǔ -The Five Grains are five farmed crops that were all important in ancient China. More generally, wǔgǔ can be employed in Chinese as a figure of speech referring to all grains or staple crops of which the end produce is of a granular nature. The identity of the five grains has varied over time, with different authors identifying different grains or even categories of grains.

The Classic of Rites compiled by Confucius in the 6th and 5th centuries BC lists 豆 soybeans, 麦 wheat , 黍 broomcorn, 稷 foxtail millet, and hemp. Another version replaces hemp with 稻 rice.

From a very early date, Han culture understood the world as composed of five elements and many corresponding pendants were enumerated, including the

- Five Directions (south, north, west, east, and center),

- Five Colors (red, black, white, qing- [green or blue, greenish black], and yellow), and the

- Five Tones (a pentatonic scale).

They were seen not merely as five crops chosen from many options but as the source permitting agrarian society and civilization itself. “Squandering the Five Grains” was seen as a sin worthy of torment in Diyu, the Chinese hell.

As the emperor was seen as an embodiment of this society, the behavior towards the Five Grains could take on political meaning:

As a protest against the overthrow of the Shang Dynasty by the Zhou, Boyi and Shuqi ostentatiously refused to eat the Five Grains. Such rejections of the grains for political reasons underwent a complex development into the concept of bigu, the esoteric Taoist practice of achieving immortality by avoiding certain foods.

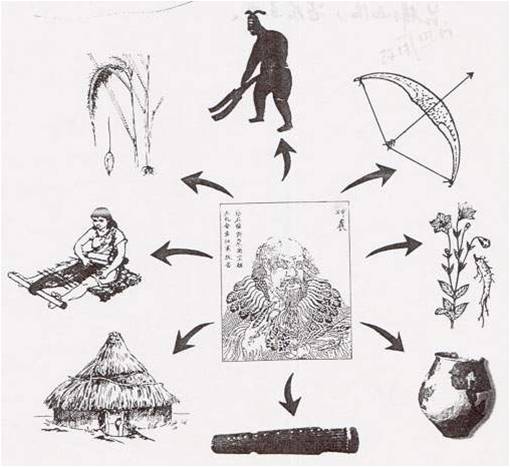

THE GOODS OF RICE AND AGRICULTURE

There were various traditions regarding which of the early Chinese emperors introduced the Five Grains and several gods of agriculture. Also there were all sorts of deities or beings in charge of bringing rain, drought, and various cyclical phenomena such as day and night or the various seasons in their proper order, which are vital aspects of successful agriculture. Other myths include the invention of fire and the invention of fermentation.

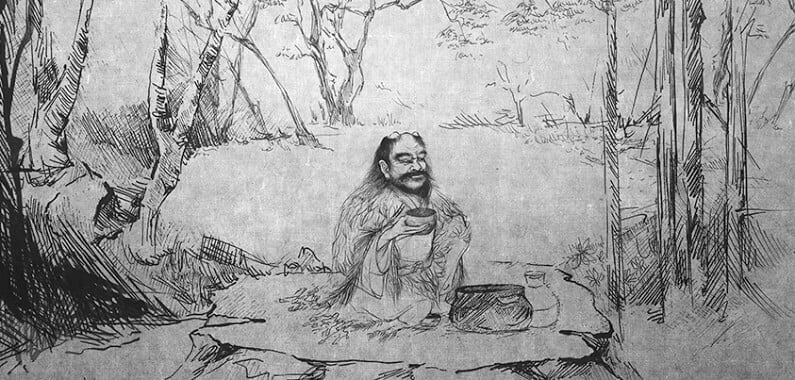

神农 Shennong

When learning about tea in China, we been told about Shennong (also spelled Shen Nong), the Divine Farmer in Chinese myth. Sima Qian’s chronology placed him around 2737–2699 BC. T

his Chinese culture hero was credited with the development of agriculture and he sowed the first rice on earth. He was often conflated with Yandi (the “Flaming Emperor”) and is also sometimes described as the Wugu Xiandi or “Emperor of the Five Grains“.

Shenong also taught people to examine the land and to cultivate it according to its quality (dry or wet, fertile or barren, high or low, etc.)

He is generally credited with having invented basic agriculture, including the plow; although he seems to have originated as a god of the burning wind, which is perhaps a reference to slash-and-burn agriculture. He also gained fame for inventing many other cultural items. For example, he made the pestle, mortar, bowl, pan, pot, rice steamer, well and kitchen range.

In the Shennongjia (“Shennong’s Ladder”) area of Hubei, an oral epic poem titled the Hei’anzhuan (“Story of Chaos”) describes Shennong also finding the seeds of the Five Grains:

Shennong climbed onto Mount Yangtou,

He looked carefully, he examined carefully,

Then he found a seed of millet.

He left it with the Chinese date tree,

And he went to open up a wasteland.

He planted the seed eight times,

Then it produced fruit.

And from then on humans were able to eat millet.

He sought for the rice seed on Mount Daliang,

The seed was hiding in grasses.

He left it with the willow tree,

And he went to open up a paddy field.

He planted the seed seven times,

Then it produced fruit.

And from then on humans were able to eat rice.

He sought for the adzuki bean seed,

And left it with the plum tree.

He planted it one time.

The adzuki bean was so easy to plant

and was able to grow in infertile fields.

The soybean was produced on Mount Weishi,

So it was difficult for Shennong to get its seeds.

He left one seed of it with a peach tree,

He planted it five times,

Then it produced fruit,

And later tofu was able to be made south of the Huai River.

Barley and wheat were produced on Mount Zhushi,

Shennong was pleased that he got two seeds of them.

He left them with a peach tree,

And he planted them twelve times,

Then later people were able to eat pastry food.

He sought the sesame seed on Mount Wuzhi,

He left the seed with brambles.

He planted it one time.

Then later people were able to fry dishes in sesame oil.

Shennong planted the five grains and they all survived,

Because they were helped by the six species of trees.

In Shennongjia, Shennong is variously called

King Yan, God of Five Grains, Shennong the Great Emperor, the Ancestor of Farming, the Great Emperor of Medicine, God of Earth, and God of the Field.

He is also worshiped as the patron god of farmers, rice traders, doctors of Chinese medicine, and more.

黃帝 Huangdi

Huangdi, the Yellow Emperor, (also spelled Huang Di) placed 2699–2588 BC by Sima Qian, was also credited in ancient texts as the first teacher of cultivation and culture hero to his peoples.

Huangdis myth refers to his many cultural inventions. In these myths he is depicted as the fountainhead of Chinese culture and civilization. He drilled the wood for fire, and then cooked fresh meat. By following his lead, his people did not suffer stomach diseases from then on. He hollowed a tree trunk to make a boat and cut branches to make oars. Therefore people could go to distant places by water.

He tamed cattle and horses to draw carts so that people could use them to carry heavy goods. He invented the wood cart, and that is why he was also called Xuanyuan ( xuan refers to a high-fronted, curtained carriage used in ancient times, and yuan refers to the shafts of a cart). He cut trees and used them to build a variety of houses to protect people from wind and rain. He invented hats, crowns, and clothes.

He cut wood to make pestles, and dug earth to make mortar. He made a cauldron to steam rice. He made coins. He found the way of measuring weight, and invented the clepsydra for measuring time. He started the football game.

After he met the goddess Xiwangmu, he made twelve mirrors, and used one in each month. So it was also Huang Di who invented the mirror. He invented coffins for the dead. After he killed Chiyou, he buried him, and that originated the custom of burial.

Various myths and legends continue to attribute many inventions and discoveries to him, such as music, writing, Chinese medicine, the art of war, the interpretation of dreams, and astronomy.

In other myth versions he is said to have made the rules for wedding ceremonies, distributed lands and built the country, and started rituals and markets. All in all, as an ancient writer noted,

“All of the techniques and crafts are started from Xuanyuan”.

Shiwu Jiyuan, The Origin of Items, written in the Song dynasty, chapter 7

后稷 Houji

Houji (also spelled Hou Ji) or Ji Qi, especially in more historically-oriented contexts. Posthumously, he was better known as Houji, from hou, meaning “prince/deity/spirit”, and ji, meaning “agriculture”, according to K. C. Wu .

Lord Millet is sometimes credited with the original provision of millet from heaven to mankind and sometimes credited with its exemplary cultivation. Lord Millet was a title bestowed upon this figure by King Tang, founder of the Shang dynasty, and may have been an early position in the Chinese government. He was later worshiped as one of the patron gods of abundant harvests, like Lai Cho.

Like many deities in Chinese mythology and belief, Houji also died and was buried. Even after his death, he was still associated with cereals and plants. According to Shanhaijing (chapter 18),

Houji was buried in the wilderness of Duguang, where the Black River went through. Here grew good tasting beans, rice, sticky millet, and unsticky millet. There were hundreds of grains that self seeded here and grew naturally whether it was winter or summer. Here the male phoenix sang while the female phoenix danced freely. The tree of Lingshou ( ling means “good” or “animated,” and shou means “long life”) bore fruits and flowers, and grasses and trees flourished. Here hundreds of beasts lived together, and grasses would not wither in winter and summer.

燧人 Suiren

There are various myths related to agriculture. Humans are said to have been taught the use of fire by Sui, sometimes called Suiren, and Suy-jin-she. He is also known as the Drill Man, used a fire-drill to start fires, and thus to allowing food to be cooked. Also: animal husbandry and the use of draft animals, inventions of various agricultural tools and implements, the domestication of various species of plants such as rice and ginger and radishes, the evaluation and uses of various types of soil, and irrigation by digging wells.

Other myths include events which made agriculture possible by destroying many suns in the sky or ending the Great Flood.

HISTORY OF 稻 RICE CULTIVATION IN CHINA

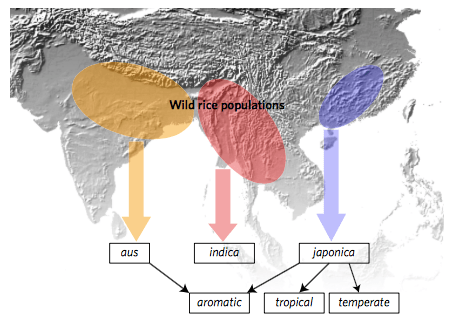

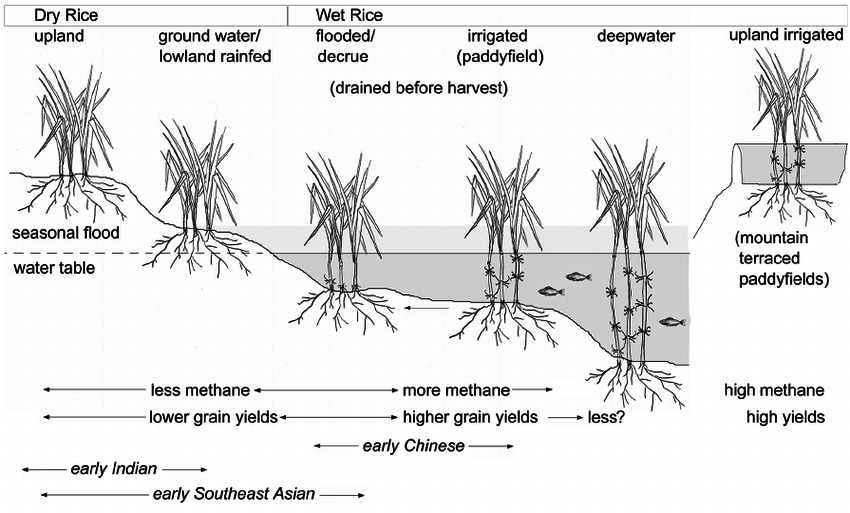

Archaeologists have determined that rice was cultivated between 9,000 and 11,000 years ago. They think rice initially sprang up from the Himalayas to Thailand, Myanmar and South China. While the early rice in China was ancestral to the subspecies japonica, another major subspecies of rice, indica has roots in India, where rice use is established by c. 6500 BC at the site of Lahuradewa in the middle Ganges Valley.

Rice was a wild wetland species which was brought under human management in artificial wetlands in Neolithic China. The evidence from Tianluoshan indicates that domestication process for rice was still underway at 4600 BC, but it had crossed the tipping point when domesticated forms outnumbered wild forms in the local populations. It is possible that the process began as much as 2,000 years earlier, but adequate archaeo- botanical evidence is still missing.

Many of these dates are approximate.

8500–7700 BC In northern China, the Nanzhuangtou culture on the middle Yellow River around Hebei had grinding tools.

5000–3000 BC By the Yangshao culture, the peoples of the Yellow River were growing millet extensively, along with some barley, rice, and vegetables; wove hemp and silk, which indicates some form of sericulture; but may have been limited to migratory slash and burn farming methods.

3000–2000 BC The Longshan culture displays more advanced sericulture and definite cities. China’s rice-fish agriculture includes the typical diet, dried fish and rice.

5000–4500 BC The Hemudu culture around Hangzhou Bay south of the Yangtze certainly cultivated rice. The Hei’anzhuan lists millet, rice, the adzuki bean, the soybean, barley and wheat together, and sesame as the “five” grains.

The various people (such as Baiyue) who succeeded to these areas were later conquered and culturally assimilated by the northern Chinese dynasties during the historical period.

From China to India and Indonesia rice spread to Korea and Japan, and later to Europe, South America and North America.

During these ancient times, rice served as money. Farmers in ancient Asia often paid their taxes in rice.

In Japan, where special glutinous rice was cultivated, farmers grew this crop for export, and sold it for high prices. Japanese farmers could not afford this rice, so they imported cheap rice from the Chinese mainland; the poorest ate millet instead. Much later, in the early 20th century, the Japanese spread rice to Australia, where it is now a significant crop.

Rice is not noted in the Bible; rice is not mentioned by ancient Egyptians. In the fourth century BC, Alexander the Great mentioned rice for the first time, saying it came from India. Later, the Greeks paid little heed to rice. The Arab conquerors of the eighth century brought Chinese rice (via India) to Spain. The Spanish in turn passed rice along to Italy and France, where it eventually spread via imperialism and colonization throughout the rest of the world. See the RICE TIMELINE for more info.

RICE- Oryza sativa

Oryza sativa contains two major subspecies: the sticky, short-grained japonica or sinica variety, and the non sticky, long-grained indica variety. Japonica varieties are usually cultivated in dry fields, in temperate East Asia, upland areas of Southeast Asia, and high elevations in South Asia, while indica varieties are mainly lowland rices, grown mostly submerged, throughout tropical Asia. Rice occurs in a variety of colors, including white, brown, black, purple, and red rices. Black rice (also known as purple rice) is a range of rice types, some of which are glutinous rice. Varieties include Indonesian black rice and Thai jasmine black rice.

Ancient Chinese farming methods

There are potentially many different forms of rice cultivation, including artificial wetlands (paddy-fields), cultivation on natural monsoon rains and river inundation and even inclusion of rice in slash-and-burn agriculture of some tropical mountain regions.

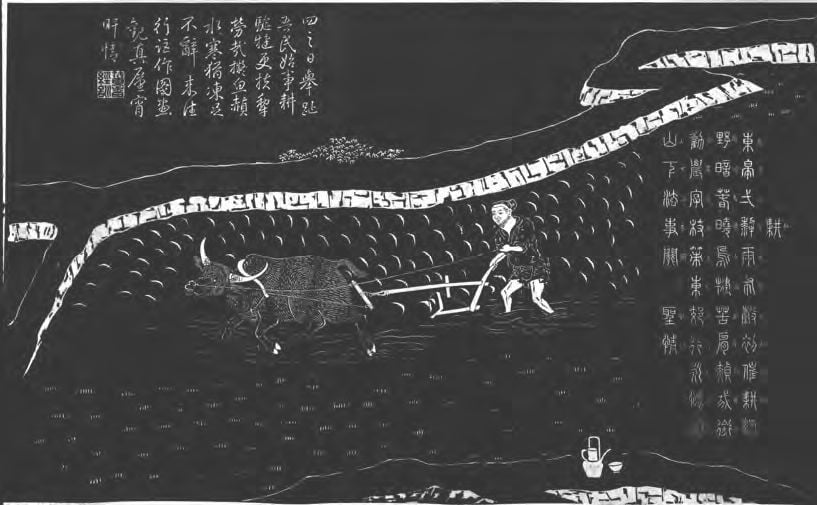

The Method Of Row Crop Ancient Chinese Farming

Seeds are planted in rows rather than following other methods of sowing like broadcasting or scattering the seeds. This facilitated the ancient farmers to irrigate the fields easily and derive maximum yield of crops.

Irrigation Control Technique

Irrigation and wet farming methods were vital parts of ancient Chinese farming.

The Dujjangyan irrigation system was built as an ancient farming technique, it is so effective and strong that it survives even until today. It had been constructed for more than 2200 years ago. This dam was built to control the floods of the Minijiang River. Even till the present day, this dam lets water as well as aquatic life to pass through. Most of the modern as innovative dams restrict the flow of water.

The Farming Tools

Around the third century BC, iron plows became improved in their designs and efficiency. The casting techniques improved and also the availability of iron doubled in the markets. The new design of plowshares was also known as Kuan. The iron plows brought a lot of facilities to the Chinese farmers. Seeds could be sown much easier with them in the furrows.

dynasty, reign of the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1736–95). Stone tablet prints on a scroll.

Collection of Alan Kennedy and Kokoro Oriental Art.

Another important tool used by the ancient Chinese in agriculture was the waterwheels. Grains were Ground with the help of water power. In the 2nd century BC, China was dependent on water power for milling its grains.

Modern Chinese farming methods

Rice duck farming

Ducks are raised on rice paddies and feed on pests and weeds. Which means the farmer doesn’t have to use earth and water-ravaging chemical pesticides and herbicides on their plants. The ducks also churn up the water with their feet helping to get more oxygen to the rice plants roots, thereby boosting growth. Duck droppings are also an excellent, natural fertilizer for rice plants. Rice duck farming is already an Asia-wide success story.

Rice fish farming

For over 1200 years farmers in Southern China have been employing rice fish farming. Recent scientific research from Zhejiang University has shown that paddies which simultaneously raise fish require 68% less chemical pesticide and 24% less chemical fertilizer than the mono culture rice system. Like ducks, the fish feed on pests and weeds. This method has been designated a “globally important agriculture heritage system” by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

Inter-cropping system

Growing two or more crops in proximity helps reduce disease outbreaks. This technique is particularly effective at reducing loss from rice blast disease, a destructive fungus that causes damage on panicles and leaves, killing them before the rice grains can form. This system has proven so popular among farmers that by 2004 it had been adopted on more than 2 million hectares of farmland across China.

Light trap

Light traps are simple but effective devices used at night in the rice fields. When switched on the light lures in insects such as leaf hoppers, plant hoppers and stem borers. The practice has proven effective for over 40% of rice plant hoppers and over 30% of rice leaf folder.

Integrated pest management

Integrated Pest Management (IPM) is another way to do what farmers have been doing for generations: combining local knowledge. For example an IPM program might take current, comprehensive information on the life cycles of pests, along with detailed insight into their interaction with the environment, then work out an appropriate way to manage them. It’s like farming with a fine scalpel, as opposed to the blunt-force axe that is chemical pesticides.

FOLKLORE: RICE Traditions and Rituals

Rice has been associated in folklore (myths, legends, traditions, cultivation practices, songs, sayings, riddles, proverbs, folk sayings, folk literature, etc.) of different ethnic groups located in different regions of China. In addition to being a staple food and an integral part of social rites, rituals, and festivals in almost all Asian countries, it has a medicinal value too, which was recognized by the medicine systems of the region centuries ago.

Chinese and Japanese people refer to breakfast, lunch, and dinner, as morning rice, afternoon rice or noon rice, and evening rice, respectively.

Many, perhaps most, Chinese cooking employs rice in some fashion, though:

- fried or boiled rice,

- congee,

- noodles,

- spring rolls,

- breads,

- wontons and other dumplings,

- glutinous rice as a wrapping, for example in zongzis;

- rice and soy milks and beverages;

Besides serving as the main staple food, it was also used to make a great variety of products such as flour and cakes and rice is also used as fermentation starters for rice wines.

During the period before the Qin Dynasty (221 BC – 206 BC), rice had become a specially prepared food. It was also used to brew wines and offered as a sacrifice to the Gods. What’s more, rice was delicately made into different kinds of food, which played an important role in a number of traditional Chinese festivities.

During the Southern, Qianfu Dynasty (1127 to 1279 CE) many kinds of wines and pastries were found in Hangzhou. About twenty kinds of pastries and nine kinds of rice gruels were listed. There were also special kitchens for making dumplings. In the Records of Grain written by Wu Zimu, lists the kinds of rice, pastries, cakes and dumplings on sale at the rice shops. Hundreds of varieties of wines, glutinous and rice vinegars are on the list.

Chinese medical scholars believed paddy rice was capable of

“replenishing the body and nourishing energy” and “of consolidating energy and producing saliva”.

Indeed, the nutrient and medical value is known.

As medicine the Chinese added rice to their prescriptions to

“protect the stomach, support the good and remove the evil within the body”

The five grains continue to be used in ritual contexts, as in the Min Nan custom of creating a Taoist stove to cook Chui Zhao Fan, a meal for the Kitchen God in which five dry seeds are placed into a slot in the chimney of the stove. Casual worshipers may simply use any five beans (e.g., of different colors) instead of any particular set of grains.

As for Myths, History and Folklore of RICE in China- Rice is still offered by the gods and sometimes venerated as such.

田地歌 Tian’te- Field Songs

Field songs are folk songs with a long history, which are popular and sung among farmer who work in the rice-growing field in busy farming seasons in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtse River. Every step of rice agriculture has his songs.

Their typical singing form is that a master singer sings it with the accompaniment of gongs, drums, suona and other instruments, and it is characterized by large structure, dozens of interlinked melodies, such as “Jiashan field song” of Zhejiang Province, “rice-seedling-transplanting work song” of Jiangsu Province, “tian shan’ge” of Shanghai.

In addition, there are diverse names and types such as:

- transplanting gong and drum song,

- weed-pulling gong and drum song,

- cart and water gong and drum,

- fanqiang,

- washan (digging mountains) drum song,

- wadi (digging field) drum song,

- jiao-ge gong and drum song,

- hua haozi work song.

秧歌Yangge- Harvest dance

Just like the differences between China’s different regions, the ethnic and folk dances are unique and nothing like the serious classical Chinese dance. There are various styles of Yangge, which literally translates as “rice sprout song.” Harvest Joy, was in a style called “Da Yangge,” or “The Big Yangge.”

Some dancers dress up in red, green, or other colorful costumes, and typically use a red silk ribbon around the waist. They will swing their bodies to music played by drum, trumpet, and gong. More people will join in as they see Yang Ge going on and dance along. Some dancers use props like the waist drum, dancing fan, fake donkey, or litter. In different areas Yangge is performed in different styles, but all types express happiness.

Like other ethnic and folk dances, the dance movements originate from country daily life. Even the names of the movements are true to life, such as the “rolling up sleeves step,” which is essentially rolling up your sleeves while stepping. It’s full of sudden movements and awkwardly angled poses, with a hint of silliness.

Men can be strong and courageous, like in Recalling the Great Qin or the Tang Court Drummers, and they can also be playful and carefree, like in the Little Mischievous Monks. They can be proud Mongolians on galloping horses, or pious Tibetans amidst snow-capped mountains. Or they can be the happy-go-lucky farmers.

Myths, History and Folklore of RICE in China- FESTIVALS AND RICE

龍船節, 五月節 Dragon Boat Festival

The Chinese Dragon Boat Festival is a lunar holiday, occurring on the fifth day of the fifth lunar month. The Festival is celebrated by boat races in the shape of dragons. Competing teams row their boats forward to a drumbeat racing to reach the finish end first.

The boat races are traditional customs to attempt to rescue the patriotic poet Chu Yuan or Qu Yuan. Chu Yuan drowned,- committed suicide by jumping into the Miluo River, on the fifth day of the fifth lunar month in 277 BC

Chinese people before throw bamboo leaves filled with cooked rice into the water. Therefore the fish could eat the rice rather than the hero poet.

Also zongzi, made of glutinous rice, are thrown into the river. Today this turned into the custom of eating zongzi or tzungtzu and rice dumplings.

春節 Spring Festival

Rice is a central part of the Spring Festival or lunar New Year Eve dinner. On this occasion, Chinese families make New Year’s cake and steamed sponge cake from flour turned from glutinous rice. The cake is called gao, having asimilar sound to another gao, meaning high. Instead of eating dumplings and New Year cakes, people in Sichuan enjoy hotpot, and Zhaoqin people usually have Zong Zi (traditional Chinese rice-pudding).

People eat these cakes in the hope of a good harvest and higher status in the New Year. The cakes and the New Year’s dinner symbolize people’s wishes for a better future. May you become rich- prosperous in the coming year! Red envelope, please. Let me start to become rich by getting money from you.

恭禧發財 Gong Xi Fa Cai.

紅包拿來 Hong Bao Na Lai.

Hong Bao is a red envelope. Red is the luckiest color in China. During Chinese New Year, parents give cash gifts in red envelopes to their children. So hong bao is cash gift or lucky money. Na Lei means Bring it to me. Chinese, in addition to Happy New Year, 新年快樂 xīn nián kuài lè- say “May your rice never burn!”.

Usually the celebrations last for 16 days, from the new year eve to the 15th day of Chinese new year ending with the lantern festival.

灶君 Kitchen God

Each year during Chinese New Year, the Kitchen God the 4th day of the new year, returns to heaven to report on what the family has done throughout the year.

The Kitchen God is also called ZàoJūn or Yu Huang, the emperor of heaven, to watch over each family and record what they do throughout the year. A paper picture of the Kitchen God is hung in a prominent location in the kitchen.

Celebrating the birthday of millet

The eighth day of the Chinese New Year is believed to be the birthday of millet, an important crop in ancient China. According to folklore, if this day is bright and clear, then this whole year will be a harvest year; however, if this day is cloudy or even rainy, then the whole year will suffer from poor harvest.

Although millet is no longer among the staple food in China, the celebration of this day is still of great significance. The aim of this day, which is to attach importance to agriculture and cherish food, still matters. This is especially important to children to form a good habit to cherish food. So, on this day, parents can take their children to the villages or the fields, and introduce some basic agricultural knowledge to the children. They can also encourage their children to take part in the cultivating of the crops, which can help children experience the difficulty of agriculture work.

The birthday of Jade Emperor, the supreme Deity of Taoism

The ninth day of the Chinese New Year is the birthday of the Jade Emperor (the Supreme Deity of Taoism). According to Taoist legend, all the deities of the heaven and the earth will celebrate this day. And there will be grand ceremonies in Taoist temples.

First full moon of the new year

The 15th night of the 1st lunar month is the first full moon of the New Year. People eat rice dumplings, known as Yuanxiao in the north and Tangyuan in the south – yuan means of satisfaction, hoping everything will turn out as they wish.

Double Nine festival

Rice is made into Double Nine festival cakes on the 9th day of the 9th lunar month each year. As people have just harvested their crops during autumn they can make these cakes with fresh new rice. Many people also follow the tradition of climbing a mountain on this day.

Mid Autumn Festival

The festival was a time to enjoy the successful reaping of rice and wheat with food offerings made in honor of the moon. Today, it is still an occasion for outdoor reunions among friends and relatives to eat moon cakes and watch the moon, a symbol of harmony and unity.

This legends gave rise to the Mid-Autumn Festival of China and Vietnam, Tsukimi of Japan and Chuseok of Korea which all celebrate the legend of the moon rabbit, called also 月兔Yùtù or Jade Rabbit.

In Chinese folklore, the hare is often portrayed as a companion of the Moon goddess Chang’e, constantly pounding the elixir of life or immortality for her. In other Chinese versions the rabbit pounds medicine for the mortals.

How the Jade Rabbit got to the moon

One day, the Jade Emperor decided that he wanted some help preparing the elixir of life for the immortals. Fearing that humans would be too selfish and untrustworthy for such an important role, he thought an animal would be better suited to this responsibility. The Jade Emperor came down the Earth disguised as a beggar and went to search for a worthy animal in a forest. As a famished and frail man, he cried out for help and food and eventually three animals came to see if they could help; the monkey, the fox, and the rabbit.

The three animals were sympathetic to the old beggar’s plight and went into the forest to search for food.

The monkey returned laden with fruits he had gathered from up in the trees. The fox returned with some fish he had caught in a nearby stream.

Despite searching throughout the forest, the rabbit could not find any food for the old man from the woodland floor. When he returned much later, and saw the beggar sat next to the fire eating the fruits and the fish, the rabbit felt sad that he had been unable to find him any food. Realizing that he could sacrifice himself so that the man could eat, the rabbit threw himself into the fire in an ultimate act of selflessness.

But at that instant the beggar turned back into the Jade emperor and stopped the rabbit from being burned. Having found the most noble of creatures to take on the role of creating the elixirs, the Jade Emperor carried him up to the moon, where he learned to make divine medicines and be kept safe from humans wishing to steal the elixir of life.

The rabbit worked hard and learned to create the divine medicines, eventually mastering the skills required to pound the right ingredients together to create the elixir of life. The Jade Emperor was so delighted with the rabbit that he made the rabbit’s fur a dazzling white. The heavenly glow from the rabbit’s smooth and bright fur was so bright and beautiful, that it looked like precious jade, which is why the other heavenly beings came to call him the Jade Rabbit.

If you look up at the full moon and squint slightly at the markings, you can still see the Jade Rabbit with his pestle and mortar, making the elixir of life for the immortals.

Read more legends of the Jade Rabbit

Sakyamuni

People eat porridge on the 8th day of the 12th lunar month. The porridge is made with rice, cereals, beans, nuts and dried fruit. It is said that Sakyamuni attained Buddhahood on this day, drinking chyle presented to him by a shepherdess, Sujata, which he believes led him to enlightenment. As a result people bathe Buddha statues and eat porridge on this day.

Modern Changes in Tradition

As technology changes agriculture, creating a system where harvest comes closer to a guarantee, traditions and mythology, such as this varied rice stories and Rice- Ceremonies have changed. In some places, the ceremonious aspect of rice farming is no longer as prevalent.

Asia is the most religiously diverse part of the world—Hinduism in India, Buddhism in Thailand, Islam in Indonesia, Roman Catholicism in the Philippines, mixed Taoism and Confucianism in China, Buddhism and Shinto in Japan, and so on. In all of these traditions, we found related ideas about the sacred nature of rice, its divine origin, and its special place in human life. Rice culture clearly predates the religious diversity that later became superimposed across the region.

The extents of Myths, History and Folklore of RICE in China are hardly to be seized here, there is still much more to discover.

~ ○ ~

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

Myths, History and Folklore of RICE in China and Asia:

- THE MOTHER GODDESS OF FERTILITY AND RICE

- TIMELINE: The story of rice

- INDIA: Myths, History and Folklore of RICE

- MALAYSIA: The Rice Soul- Myths, History and Folklore of RICE Beras or Nasi

- MALAYSIA: Proverbs and wise sayings in relation to RICE Beras or Nasi

- CHINA: Proverbs and wise sayings in relation to RICE 稻

- THAILAND: Mae Posop- Myths, History and Folklore of RICE

- THAILAND: Proverbs and wise sayings in relation to RICE K̄ĥāw

- INDIA: Proverbs and wise sayings in relation to RICE Chaaval

- INDIA: RICE dishes Khichri, Byriani, Kheer, Dosa &Idlly

- INDONESIA: Myths, History and Folklore of RICE Nasi

- BALI- INDONESIA: Myths, History and Folklore of RICE Nasi

- INDONESIA: FOLK TALES ON RICE

- INDIA: FOLK TALES ON RICE

- CHINA : FOLK TALES ON RICE 稻

- Ancient Chinese Farming – ancientchinalife.

- Chinese Folk Dance: The Rice Sprout Song – shenyunperformingarts.org.

- Chinese Idioms. – standardmandarin.

- Collection of Chinese Folk Songs. – chinaculture.org.

- History of rice cultivation – Ricepedia.

- How Rice Built the World As We Know It. 2015.

- How the Jade Rabbit got to the moon.

- Lihui Yang, Deming An. Handbook of Chinese Mythology – Archive.org. 2005.

- Oryza sativa.– Wikipedia.

- Rice as a Superfood. Encyclopedia of Food and Culture – Encyclopedia.com. 2018.

- Rice Culture of China.– China.org edited and translated by Li Jinhu. 2002.

- Rice: The Grain That Shapes Cultures, Traditions and Rituals – Asiarice.

- Tan Monica. How ancient Chinese farmers had it right all along, and other eco-friendly rice farming methods. 2013.

- The 24 Greatest Chinese Food Proverbs for Food Lovers.

- Yangge. Chinese New Year. Rice– Wikipedia.

Keep exploring: