There are many origin myths and much folklore about rice, it is believed that a goddesses gave rice to humans and taught them how to grow it. Religious use of rice takes place in India, China, Thailand, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Malaysia.

In Asia, the rice spirit is a goddess and often a mother figure, in Bali she is called Dewi Sri or Devi Sri. Devi Sri and Mae Posop of Thailand are treated in similar ways- respectful and protective. Discover Myths, History and Folklore of RICE in Bali.

In this Article

The Balinese people have many words for rice, and are highly organized as how to irrigate their rice fields and Rice is seen as the gift of god, venerated as Devi Sri and the subak system is part of temple culture. The Subak is a traditional ecologically sustainable irrigation system and water management plan that binds Balinese agrarian society together which the village’s Bale Banjar community center and Balinese temples.

The Balinese live with the Rice cycle that gives them the calendar, in witch the steps of rice cultivation are written, rice plays also a prominent role in ceremonies and rituals like Galugan and Kuningan.

ETYMOLOGY: Words for rice

Rice is the staple diet of the Balinese. The word nasi (rice) also means “meal”. The Balinese cannot really conceive of a meal without rice and the number of words for rice indicates its importance:

Padi – rice growing in the field or rice that has been cut but not threshed, or cut and threshed, but not husked (the husk and bran are removed at the mill, or in the old days by pounding with a mortar and pestle); the English word “paddy” comes from padi.

Gabah – unmilled rice that has been separated from the stems.

Beras – milled, uncooked rice.

Nasi – cooked rice.

There are three different types of rice that are cultivated:

Barak – red rice.

Injin – black rice, which is in fact a dark, blackberry purple.

Ketan – white sticky, glutinous rice.

There are four sacred directions, each of which has a sacred color,

red,

black,

white and

yellow.

God intended to give the Balinese rice of all these colors, but there was a problem in transmission:

Shiva sent a bird to bring the rice to the Balinese but the bird ate the yellow rice – except for a little bit which it planted under the eaves of its house. From the seeds grew turmeric, kunyit. Yellow rice does not grow in Bali, but mixing white rice with turmeric can make it yellow. This is the fourth type of rice.

Offerings of yellow rice are needed for certain offerings, and especially during Kuningan.

DEVI SRI – The Rice Goddesses

In most rice growing countries of Asia, the spirit of rice resides in the Rice Mother or the Rice Goddess. In Bali and Java, Devi Sri is the rice mother and goddess of life and fertility. She is everywhere, from everyday rituals -such as putting pinches of rice along the edges of fields to keep evil spirits and animals at bay -to grand temple celebrations with elaborate offerings of dyed rice paste, the Balinese honor their Rice Mother.

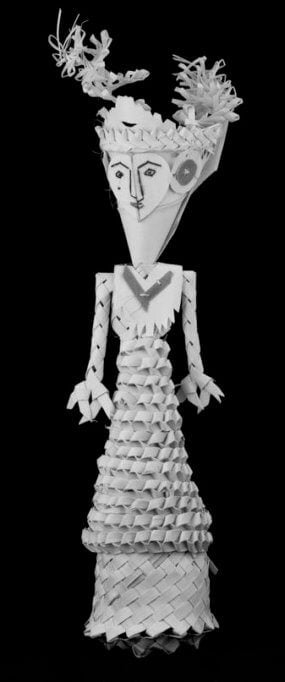

The Rice goddess, Devi Sri, is popular, she is male and female, as indeed are all the gods, people and things in the cosmos. At important times in the rice cycle, images of Devi Sri are worshiped.

The rice farmers make a Cili out of rice stalks just before harvesting. She is set up in the rice fields, in the shape of two triangles, with a pinched waist. Cili is symbolic of food and, of course, rice is food. The Cili is frequently woven into lontar palm leaf offerings called lamaks. They are placed in the rice field and hang from shrines and traditionally temporary shrines, erected outside homes in the street at Galungan and other ceremonies.

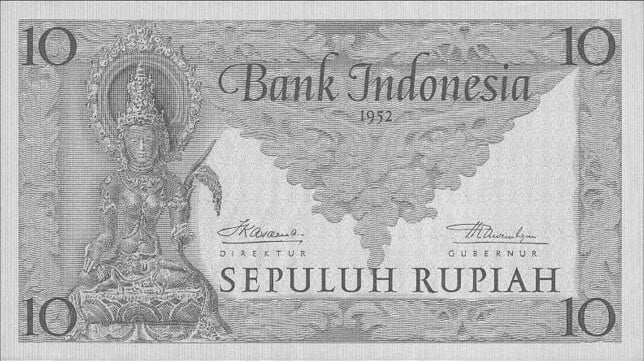

Devi Sri is believed to have control over birth and life, the rice fields and the growth of rice. In light of this, Devi Sri controls life, wealth and prosperity of Balinese rice farmers. Many ancient Javanese and Balinese Kingdoms paid outmost respect and present lavish offerings respect to Devi Sri, ensuring that they continuously have good harvests. Plentiful rice equals to wealth and survival of their kingdoms.

MYTH: Devi Sri

One major version of the Sri myth is related in the story of Sri Ma- hapunggung.

The ruler of Mendang Kamulan, Sri Mahapunggung, notes that his son, prince Sedana, has disappeared without a trace.

Suddenly an embassy from King Pulagra, the ruler of Mendang Kumuwung, appears, asking for the hand of Devi Sri, Sri Mahapunggung’s daughter. Devi Sri, however, only wants to marry someone who looks just like her brother Sedana. She flees the palace, pursued by the representatives of King Pulagra.

On her journey Devi Sri arrives in Mendang Tamtu, where Ki Buyut Wangkeng and his wife are bringing in the rice harvest. When Sri approaches the wooden block in which rice is pounded, they invite her into the house, She requests, however, that the house first be cleaned. At this point her pursuers arrive and a battle ensues, during which Devi Sri flees further, chased by Kaladru, one of the deputies. In the meantime, Batara Guru has become aware of Devi Sri’s plight. He has her informed about Sedana’s whereabouts in the forest Mendang Agung, and they are quickly reunited, after which Sedana defeats Kaladru. Sri and Sedana then decide to make a settlement in the forest. Sedana is sent to get seeds and young plants. He also brings in Ki Buyut Wangkeng. King Pulagra now attempts to acquire Sri by force but is defeated. After this Sri and Sedana are urged to marry, but they refuse and Sedana is separated from Sri.

In an alternate reading Sri and Sedana run away from the palace together and refuse to return.

When they lay sleeping, the gods change Sedana into a swallow and Sri into a large snake (ular sawah; snake of the rice fields).

Alternately, when Sri Mahapunggung hears that his children have not returned, he sighs,

“Oh Sri, will you change your skin like a snake, oh Sedana, will you nest in strange parts like a swallow? ”

Owing to his great spiritual powers, these things then really happen.

In any case, upon awakening, Sri and Sedana are afraid of each other and separate.

Sri then enters a field of ripening rice. The farmer who owns this field dreams of her, catches her, and locks her in his rice shed. She then appears in his dreams and advises him on how to protect his unborn child from several forms of death.

Bahatara Guru and Devi Sri

Once upon a time, Bhatara Guru (the head of Gods) who resides in heaven held a great ceremony. It is a tradition that each god should help in the preparation of the ceremony. But the great dragon Ananta Boga looked so sad since he could not help with anything because he did not have hands or feets. It made him sad, he cried alone, but a miracle occurred, his tears that touched the land turned into three eggs. He took those eggs on his mouth; and planned to give Bhatara Guru the eggs as a consolation for his inability in helping the preparation of the ceremony.

On the way, he met another god, the god greeted him, when he answered two of his eggs fell into earth and hatched. One produced a rat and the other a boar. Realizing his mistake, Ananta Boga kept silence on the rest of the way, until he arrived in front of Bhatara Guru. He told Bhatara Guru what happened on him, and presented the remaining egg. Bhatara Guru accepted the egg.

After a couple of days, a beautiful girl came out from the egg. Bhatara Guru named her Devi Sri and loved her very much, that made several goddess jealous on her. They tried to make Devi Sri ‘disappear’ from heaven. One day they manage to poison Devi Sri, she died and the wicked goddess buried her body deep in the earth. After a couple of days a plant (rice) grew from the place where Devi Sri was buried.

Bhatara Guru realized that the plant was Devi Sri.

He came to the earth and told humans to keep that plant especially from rat and jungle pig disturbance since the plant was a goddess and it could give a welfare for human being. But if they did not keep it, they would get a disaster.

Variant: Bahatara Guru and Devi Sri

There is another the story of Devi Sri’s origin.

Anta, a deformed god was depressed by his failure to find any gift for Batara Guru’s new temple. He wept three tears, which turned into eggs. An eagle swept down and forced him to break the eggs. He smashed two of them but the third then hatched and released a beautiful baby girl. She was given to Batara Guru’s wife, Uma, to be breast-fed and was named Samyam Sri. Sri grew up to be very beautiful and Batara Guru lusted after her. This was forbidden, as she was technically his daughter.

He tried several times to rape her. This angered the other gods so much that, to rescue her, they killed her and buried her body.

Plants grew from various parts of it. Sticky rice grew from her breasts and ordinary rice from her eyes. In remorse Batara Guru gave these to man as food. Sri became a goddess called Devi Sri and became the spirit of fertility, protectress of the rice fields and guardian of rice barns.

Rice farmers and Devi Sri

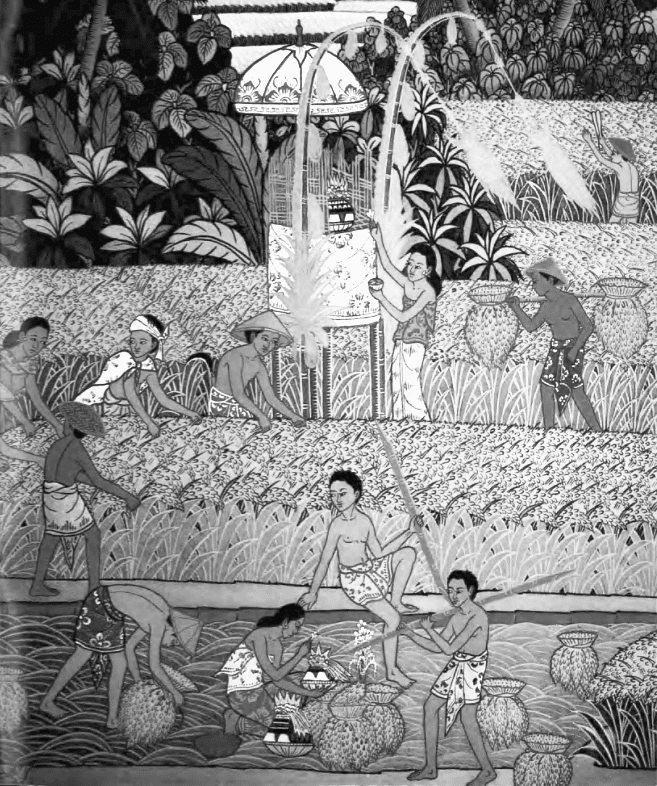

The divine rice plant is considered an animated female being and is treated with respect. Each stage of farming is carried out on an auspicious day, accompanied by appropriate offerings. Rites of passage, just like for a human being, are conducted.

Some of the rituals are carried out by the farmer at a small temporary shrine in the upstream corner of the field, others at the water temples. The rites include water opening, field preparations, transplanting, growth, flowering and harvesting.

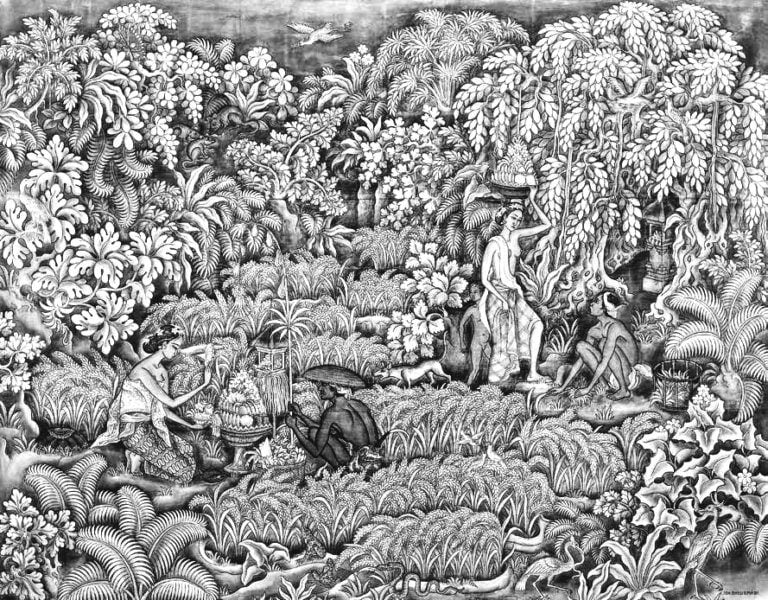

The rice cycle is a life cycle. Spiritual connection, work and celebration go together. Before a new planting, offerings are made to the rice goddess, Devi Sri, to bless the harvest and meetings are held with the local Subak, to decide how water will be distributed. Fields are ploughed by hand, by cow or buffalo, or even by more time saving mechanical means! Fields are checked and flooded and the small nurseries of baby seedlings glow bright almost luminescent green in the tiny nursery fields. When the priests choose the right and propitious day, planting can begin. Even though it appears to be backbreaking work, the planting is fast and takes just a few hours, especially when a group of neighbors work together.

Before the planting

Just before planting, the fields are flooded and ploughed by oxes or machines. Tractors are used in Bali, but not everywhere. The fields look like reflecting mirrors. Then they are fertilized. When the Balinese plant the first rice seedlings in the field, a special planting pattern is followed for the first nine seedlings after offerings are made to Devi Sri. Multicolored cones of cooked rice are used for recalling the nawa sanga (rose of the winds).

After planting

After planting – by hand over several days – the yellow-green shoots of young rice sprout up. This is a dangerous time. Scarecrows, wind chimes, bamboo bird- scarers and pulleys of cloth or plastic are put up to frighten the birds, kites are used too. People keep watch and yell at them.

We have seen an old farmer sitting on the edge of the field pulling a sting to move metal cans, placed in the middle of the paddy, the noise is unpleasant.

The wedding of Betari Sri Dewi and Betara Sedana

In Bali, the rice goddess is formally known as Betari Sri Dewi and her consort is Betara Sedana. This divine couple is the focus of a great deal of Balinese ritual, extending from the rice fields to the most sacred temple in the land, Pura Besakih. There is an annual “wedding” is held for Betari Sri Dewi and Betara Sedana to seek an ample rice harvest and a bounty of material wealth. Their union thus symbolizes sufficiency and completeness of the material requirements needed to sustain a good and proper life.

In these rituals and others, Balinese deities can be invoked to take up temporary residence in sacred vehicles, including life-like figures made of coins. The figures can be used for different deities, and technically without being “inhabited” they are nameless, but a male and female pair like this, known collectively as the Rambut Sedana, is in practice strongly equated with Betari Sri Dewi and Betara Sedana.

This Rambut Sedana was collected in the 1930s by the American dancer Katharane Mershon who was well versed in the ritual life of the community of Sanur, where she lived. Fully dressed and perhaps resembling play dolls to Western eyes, the figures are actually among the most revered objects in Balinese religion.

~ Roy W. Hamilton

Harvest

Two months later the rice will have grown taller and green. When they turn, the plants are mature and ready to harvest. It takes about five months in all. After harvesting, the stubble in the fields is burnt or alternatively flooded, so that the old rice stalks slowly decompose under the water.

The upstream corner of the rice field is sacred. Here offerings are made to Devi Sri. At harvest time a sacred image of Devi Sri herself is made from rice that grows closest to this spot. The “first fruits ritual” occurs before the harvest, in which rice dolls, Cili, symbolizing Devi Sri are made and placed in the rice granary or at home to ensure a bumper harvest.

The Balinese honor Devi Sri by offering dyed rice paste at celebrations. The jaja, which is made from colored rice paste of different shapes and prepared in different ways, is used for decorating offerings of fruits and flowers at merry or solemn Balinese ceremonies or festivals.

At many other festivals, cooked and colored rice cakes are offered, decorated with flowers and palm leaves.

Some farmers believe that Indra (Lord of the Heavens – of rain) taught men how to grow rice and rice is the soul of man.

Ducks in the rice paddies

Rice paddies do not just produce rice. They produce a lot of protein. There are eels, frogs and fish in the paddies. There are also dragonflies. Little kids hunt the dragonflies with long, sticky rods, pull off their wings, pierce them alive on a stick, roast and eat them.

The rice paddies also provide a living for Balinese ducks, which, by the way, cannot fly.

After the harvest, the duck farmer brings his flock of ducks, which spend the day clearing up old pieces of grain and eating insects, like brown plant hoppers, that would destroy the next rice crop if left alone.

The ducks follow the farmer home at night, keeping an eye on his piece of cloth tied to a big stick. This charming view has inspired numerous paintings.

THE SUBAK- UNESCO World Heritage

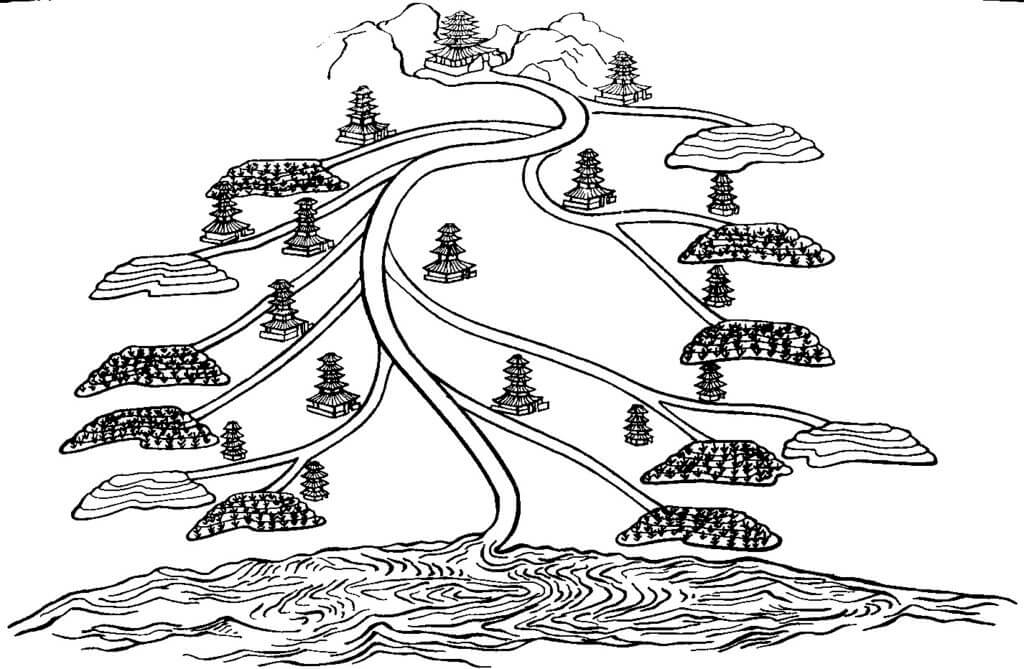

Bali’s beautiful glistening green rice fields are the result of a rice culture that has been handed down for centuries. A carefully integrated system of planting and irrigation through the UNESCO World Heritage recognized Subak system means that, rice farmers all over the island have received water to irrigate their crops. The water which starts from the deep volcanic lakes of the mountains is directed all the way down, thorough countless fields, to the sea.

The cultural landscape of Bali consists of five rice terraces and their water temples that cover 19,500 ha. The temples are the focus of a cooperative water management system of canals and weirs, known as Subak, that dates back to the 9th century.

Included in the landscape is the 18th-century Royal Water Temple of Pura Taman Ayun, the largest and most impressive architectural edifice of its type on the island. Rice farmers and temple priests regard the immense fresh water Temple of the Crater Lake as the ultimate source of water for the rivers and springs that provide irrigation water for central Bali. It is seen as the center of a sacred mandala or cosmic map of waters fed by springs lying at the wind directions points.

The Subak reflects the philosophical concept of Tri Hita Karana, which brings together the realms of the spirit, the human world and nature. This philosophy was born of the cultural exchange between Bali and India over the past 2,000 years and has shaped the landscape of Bali. The Subak system of democratic and egalitarian farming practices has enabled the Balinese to become the most prolific rice growers in the archipelago despite the challenge of supporting a dense population.

Today the rice growing cycle is about 105 days. That means they can get 3 crops of rice a year, which is a lot of rice. However, since wet rice requires a lot of water it’s better to stagger rice production so not every farmer is using water at the same time, and so you don’t have too much rice at any one time.

This requires a high level of cooperation and coordination, and so farmers work together. A group of farmers that draw water off the same canal is called a tempek (this refers to both the land and the association). The members of the tempek elect a chairman, or klian. They also cooperate on maintenance activities and religious rituals. Usually it’s the case that several of these canals feed off a common dam (empelan), and so all the tempeks that share a water source form a larger association called a Subak. There are about 1300 Subak Organizations in Bali.

While the National government controls the island of Bali, at village level (desa) more emphasis is placed on the role and impact of the Banjar; a cooperative society that determines almost every aspect of the Balinese daily life. The purpose of Banjar is to hold each other in line with the social activities such as wedding ceremony, people death, take a part of refurbishment of temple, road, cleanliness of the area, security protection and do all the activities together in economic, social and ritual field. The Banjar is lead by Klian Banjar. Meanwhile, the amount of the Banjar’s member is around 30 – 150 family leaders.

All people having land within the area of a particular Subak are citizens of that Subak (krama subak). The Subak is the primary unit of water management and is usually translated as “irrigation society”, but it is more than just this; it is an agricultural planning unit, an autonomous legal corporation, and a religious community managing virtually every aspect of cultivation.

The Subak generally has two temples: one near the dam and one near the rice fields.

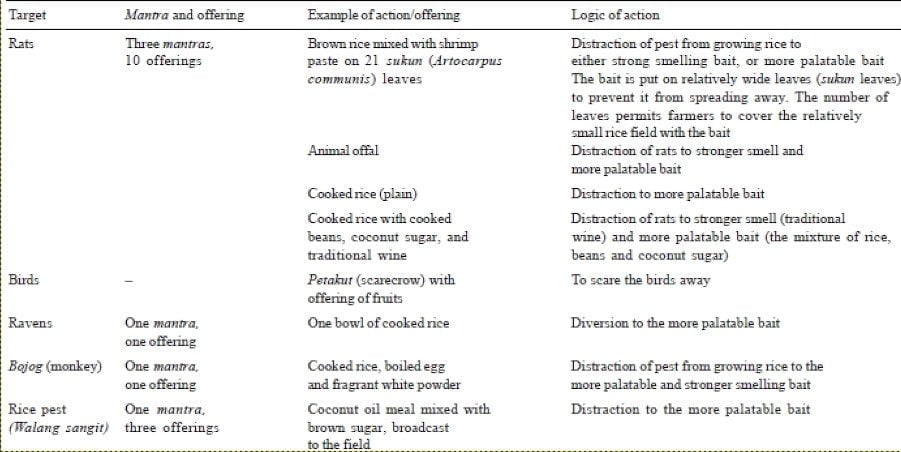

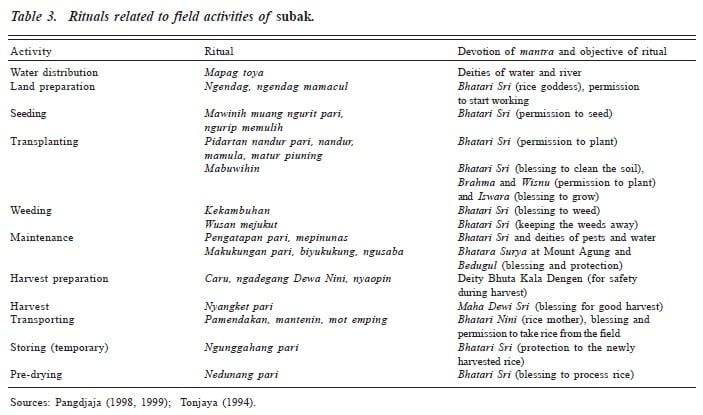

The Subak also manages all the rituals related to rice farming.

Handling Subak problems:

Each year all the Subak chiefs in a given region meet at a mountain temple, or a pura masceti. At these periodic gatherings the Subak leaders plan the ritual cycles for all the Subak temples, as well as planting schedules and water allotments. The Subak coordinates planting and harvesting for all of the tempeks so that not everyone is planting or harvesting at the same time. All of the pura mascetis fall under the authority of one of two lake temples, forming a coordinated system of water management that covers the entire island. The two water temples are Pura Batu Kau in Tabanan, which has jurisdiction over western Bali, and Pura Ulun Danau, which is the master water temple for the north, south, and eastern portions of the island.

The subak and the priests also coordinate collective work and religious ceremonies associated with cultivation. The types of work committees (seke or seka) within the subak:

- Seka numbeg – provides labor for land preparation

- Seka tandur – does rice transplanting

- Seka mejukut- does weeding

- Seka merana – does pest control

- Seka manyi- does harvesting

- Seka gebros- does rice selection

- Seka sambang – monitors water consumption.

The rituals involved are:

The Subaks have rules of management as well as a system of sanctions (sima) that keep the farmers in line. This are codified in a compact or constitution called an awig-awig.

Subaks are very democratic and decision making is done by consensus at meetings (sangkepan) that take place every 35 days (according to the Balinese calendar).

The Pawukon – The Balinese calender

The traditional Balinese calendar reflects the Rice cycle, it is called Pawukon.

A year consists of 6 months of 35 days making adding up to a total of 210 days. A number of days, which is believed to be rooted in the cycles of the thousands of years old rice growing tradition in Bali.

The calendar has 10 different week-circles, all running simultaneously. The weeks are from one to ten days long all with their unique set of names for the week days. That mean the same day often have different names, depending on which of the 10 week circles is being used. To add to the complexity, the ordering of the weekdays isn’t always the same (like in the Gregorian calendar, where Wednesday always follow Tuesday) and a 4, 8 o 9 week isn’t always 4, 8 or 9 days long, since 210 (the days in a year) can’t be divided by these numbers some weeks have extra says added.

Pawukon sets the date for many of the traditional Balinese holidays and festivals, like Saraswati, Pagerwesi, Kuningan and Galungan, that due to the Pawukon calendar is celebrated every 210th day.

Rice Ceremonies and Rituals

Rice plays a crucial role in many cultural ceremonies. One famous Balinese festival, Galungan, is uses black rice that is especially planted with 13 blessings throughout its growth. This festival

commemorates the victory of good (dharma) over evil (adharma) and is celebrated every 210 days and lasts for 10 days.

As the expression of victory, people will fit penjor – a tall bamboo splendidly decorated with black rice, woven young coconut leaves, fruit, cakes and flowers, as offerings to God. This penjor is placed on the right side of every house entrance. People are attired in their finest clothes and jewels on that day as they believe that all the Gods will come down to earth during this period.

Galungan

Often described as the Balinese Christmas, this is the most important day of the 210 day Balinese year, the start of the period during which the deified ancestors descend to the family temple and are entertained and presented with offerings and prayers. Actually, strictly, they come down five days before Galungan, they visit the cemetery, where people will give offerings as well. The villages are beautifully decorated with penjors. Each village has its own style of penjor. Business stops. Schools close.

Preparations start three days before, people look very busy.

On the first of these days bananas are bought or picked so that they will be ripe for Galungan.

Tapé, a mildly alcoholic fermented rice pudding, is also prepared.

The next day is spent making the cakes. The day before Galungan is called Pemampahan, which means to slaughter the animals, namely pigs.

The meat is finely minced and either wrapped around thick skewers and barbecued as saté or mixed into a fiery assortment called lawar.

It is also the last day to erect the penjors. Some Balinese see the penjor as a remaining element of an ancient fertility cult. It is said to represent the dragon-snake “Anantaboga”, a symbol of earth and prosperity – Anantaboga meaning unending food, with its head making up of the “shrine” and the tail its extremity. The fertility aspect is emphasized by the food hanging all along the bamboo until its extremities, as well as by the decorative bird. According to the Adiparwa story, it was a bird which brought agricultural produces to earth from the abode of the gods.

The penyor erected on the eve of Galungan, stays in place for five weeks until the Buda Kliwon of Pahang. Then it is pulled out, burned and its ashes are buried inside the compound in a final endeavor at producing fertility and prosperity.

On the day itself, always a Wednesday, in the eleventh week of the 210 day Balinese calendar, prayers are said, offerings made and families visited. There are barongs on the street, with crashing cymbals and gongs. Barong is a symbol of health and good fortune, in opposition to the witch, Rangda. It will dance outside each house for a few coins to banish the evil spirits.

Families continue to visit each other the next day. The holiday ends ten days later on the day called Kuningan.

Galungan also commemorates an historic battle, which symbolizes good over evil. In 8 CE a bad giant king called Sang Mayadenawa forbade the Bali Aga Balinese people from carrying out their religious ceremonies. With the help of many Aryas from East Bali, a fierce battle took place and the king was killed. Peace was restored.

MYTH: Mayadenawa

It is said that once upon a time, there was a powerful king, Mayadenawa, who reigned in Balingkang, about a few kilometers north of Batur Lake, Kintamani, Bangli. He also ruled such areas as Makasar, Sumbawa, Bugis, Lombok, and Blambangan. Mayadenawa was a descendant of daitya (powerful giant), son of Goddess Danu. Because of his magical power, Mayadenawa was able to transform himself into various shapes of creatures. Because of his supernatural power, Mayadenawa became arrogantly evil. He forbade Balinese people to worship God and destroyed all the shrines and temples. The plants were destroyed. Food shortages and diseases occurred. People were suffered but they did not have the courage to fight against Mayadenawa because of his magical power. Mpu Kulputih, a powerful Hindu priest, was concerned upon the suffering. He then meditated at Besakih Temple to ask for God s guidance. In his meditation, he received revelation from God Mahadewa that he should go to Jambu Dwipa (India) and ask for help. It was not clear about who went to India, but afterward it was said that a platoon of troop from heaven with complete weapons came to attack Mayadenawa. The troop was led by God Indra. The right wing of the platoon was led by Citrasena and Citraganda. The left wing was led by Jayantaka while Gandarwa led the main platoon. God Indra sent Bhagawan Narada to spy Mayadenawa Kingdom, but Mayadenawa has found out about this. Therefore, he prepared his troop to face the attack. A dreadful war broke up that caused many victims from both sides. Since God Indra s troop was much stronger, Mayadenawa’s troops ran off and left Mayadenawa and his assistant, Si Kala Wong. The battle had to be stopped, because the night has come. When God Indra s troop were still asleep, Mayadenawa came and created tirtha cetik (poisonous water) nearby. He then ran away by walking his angled feet sideways in order not to leave any footprints on the ground.

The area passed by Mayadenawa is later known as Tampaksiring which literally means angled footsteps. The toxic water poisoned God Indra s troop. God Indra then created another spring to cure his troop, called Tirta Empul (spring). The holy spring flew to form a river which is called Tukad Pakerisan (Pakerisan River). God Indra s troop then chased Mayadenawa who transformed himself into several creatures. The area where Mayadenawa transformed into manuk raya (big bird) is called Manukaya village. The area where he turned into buah timbul (a kind of vegetable) is later known as Timbul village. The place where he transformed into busung (young coconut leaf) is called Busung village while a place where he turned into a goddess (dewata) is known as Kedewatan village.

Lastly, Mayadenawa transformed himself into a huge rock. God Indra shot him to dead with an arrow. His blood flew and formed a river called Tukad Petanu (Petanu River). It is believed that the river was cursed. If it was used to water the rice field, blood would come out of the paddies and the paddies would smell. This curse will last in 1000 years.

The death of Mayadenawa was later celebrated as the victory of goodness (dharma) against evil (adharma). This triumph day is commemorated every six months (210 days) of Balinese almanac and is called Galungan. It is called Galungan, possibly because it is occurred on wuku Galungan (based on Balinese almanac).

Kuningan

Kuningan is also a day of prayers and visiting. Special offerings are made of yellow rice, rice made yellow by turmeric. The word for yellow is kuning. This marks the day the ancestors return to heaven. Actually, strictly they returned five days earlier. It commemorates the spirits of the heroes who were killed during the battle against Sang Mayadenawa.

Asia is the most religiously diverse part of the world—Hinduism in India, Buddhism in Thailand, Islam

in Indonesia, Roman Catholicism in the Philippines, mixed Taoism and Confucianism in China, Buddhism and Shinto in Japan, and so on. In all of these traditions, we found related ideas about the sacred nature of rice, its divine origin, and its special place in human life. Rice culture clearly predates the religious diversity that later became superimposed across the region.

As technology changes agriculture, creating a system where harvest comes closer to a guarantee, traditions and mythology, such as this varied rice stories and Rice- Ceremonies have changed. The ceremonious aspect of rice farming is no longer as prevalent.

The extents of Myths, History and Folklore of RICE in Asia are hardly to be seized here, there is still much more to discover.

~ ○ ~

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- THE MOTHER GODDESS OF FERTILITY AND RICE

- TIMELINE: The story of rice

- MALAYSIA: The Rice Soul- Myths, History and Folklore of RICE Beras or Nasi

- MALAYSIA: Proverbs and wise sayings in relation to RICE Beras or Nasi

- CHINA: On the origin of Rice 稻 – Myths, History and Folklore

- CHINA: Proverbs and wise sayings in relation to RICE 稻

- THAILAND: Mae Posop- Myths, History and Folklore of RICE

- THAILAND: Proverbs and wise sayings in relation to RICE K̄ĥāw

- INDIA: Proverbs and wise sayings in relation to RICE Chaaval

- INDIA: Myths, History and Folklore of RICE

- INDIA: RICE dishes Khichri, Byriani, Kheer, Dosa &Idlly

- INDONESIA: Myths, History and Folklore of RICE Nasi

- INDONESIA: FOLK TALES ON RICE

- INDIA: FOLK TALES ON RICE

- CHINA : FOLK TALES ON RICE 稻

- Hamilton Roy W. Using art to teach culture. Rice in Asia. 2004.

- “Rice as a Superfood.” Encyclopedia of Food and Culture. Encyclopedia.com. 2018. http://www.encyclopedia.com/food/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/rice-superfood

- Balinese Ceremonies. http://www.murnis.com/culture/balinese-ceremonies/

- Balinese Rice. http://www.murnis.com/culture/balinese-rice/

- Balinese Symbolism. http://www.murnis.com/culture/balinese-symbolism/

- Courtesy of http://balistarisland-indonesia.blogspot.co.id

- Couteau Jean. Penjor: The Meaning Behind Bali’s Decorative Bamboo Poles. 2017.http://nowbali.co.id/penjor-meaning-behind-balis-decorative-bamboo-poles/

- https://kepemangkuanekajati.blogspot.com/2016/07/candra-preleka.html?view=classic

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=collectie+tropenmuseum+Devi&title=Special:MediaSearch&go=Go&type=image

- Idarta Wijaya. A Balinese Folktale: Devi Sri (the Rice Goddess). 2007.

- Immage: Donald Stuart Leslie Friend (6 February 1915 – 16 August 1989) was an Australian artist and writer. Herding the ducks.https://cookshillgalleries.com.au/products/herding-the-ducks-bali

- Mayadenawa.

- Rice and its history. https://www.sunria.com/pages/rice-and-its-history

- Rice: The Grain That Shapes Cultures, Traditions and Rituals. www.asiarice.org

- Subak (irrigation). Indonesian Folklore. Rice in Indonesia. Wikipedia.

- Temples and Subaks. Geografika Nusantara. 2011. https://keith-travelsinindonesia.blogspot.co.id/2011/12/holiday-in-bali-1-temples-and-subaks.html.

- The cultural landscape of Bali. whc.unesco.org

- Thomson Gale. Encyclopedia of Religion. 2005

Keep exploring: