Scientifically known as Panthera leo persica, the Asiatic lion is a symbol of power and royalty, deeply embedded in the cultural and natural heritage of India and beyond. Discover history, myth & folklore of the Asiatic Lion or Panthera leo persica.

In this Article

The king of the jungle

The season was dry; the grass was withered, yellow-gray. The lions were lying completely melting into the landscape, and I…

I didn’t see them at all!

The sublime brutes there are my first wild Panthera leo leo, also known as šer in Persian, Simha in Sanskrit, Sher शेर in Hindi, Singha সিংহ, Singam or Chinggam சிங்கம் in Tamil, and in Urdu babar or bibar ببر is rendered both as ‘lion’ and as ‘ tiger ‘.

With their regal presence and fierce charisma, these majestic creatures inspire awe and respect unlike anything else.

A creature that has a face as inscrutable as an Egyptian sphinx’s.

We were glad to be inside a jeep even as the lions were just lazing around in the shade of acacia trees.

Darsh, our driver told us: ” Do not be scared, the lion is a royal animal, he does not eat humans, usually”.🦁

The lion’s habitat

The dry, deciduous forest of Gir, of the Kathiawar landscape of bleached grass and long flat-topped hills bristling with various spiny trees of the genus Acacia, dhok (Anogeissus pendula, or button tree), the Indian frankincense trees (Boswellia) and the Flame of the forest.

African lions live in scattered populations across sub-Saharan Africa (blue).

The Asiatic lion once ranged from the Mediterranean to India, covering most of southwest Asia.

The historic distribution included the Caucasus to Yemen and from Macedonia to present-day India through Iran (Persia) and Pakistan till the borders of Bangladesh (red).

Home of the lions: Gir National Park and Wildlife Sanctuary

Today the lions are extinct from these areas except for the Gir Protected Area in Gujarat. They were hunted nearly to extinction in India by princes, maharajas, and British nobles:

[…] ‘Venomous Snakes and Dangerous Beasts’ were being exterminated to facilitate expansion of imperial control and to protect the populace.

It is estimated that between 1875 and 1925, 80.000 tigers, 150.000 leopards and 200.000 wolves were destroyed for rewards whereas many more may have perished for which no claims may have been made.[…]

Yet in spite of this wholesale carnage, possibly as many as between 25,000 and 30,000 tigers survived in India.

By the early 1900s, sport-hunting and shooting meant numbers had reputedly plummeted to between 20 and 50 individuals.

Until the Nawab (ruler) of Junagadh, a princely state in Gujarat, banned hunting,– in his private grounds,– at the end of the 19th century.

Subsequently during the post-independence stringent protection by the State-run forest department has led to the establishment of Sasan Gir Forest as a protected area, which became a reserve in 1965 and Sasan-Gir National Park in 1975.

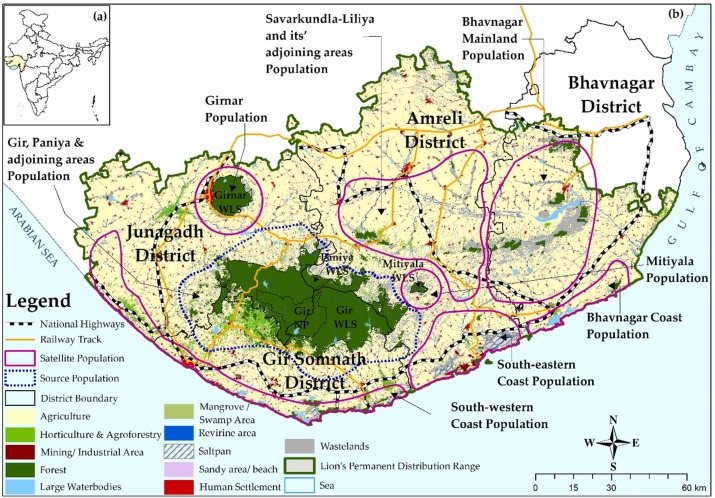

Today, due to continued conservation initiatives, the lion population has rebounded to over 600 individuals, making it a successful example of wildlife conservation.

One Canine distemper outbreak could decimate the breed.

The Gir hill system has an area of approximately 1,800 square kilometers, of which a little over 1,400 form the Gir National Park and Sanctuary.

The Gir Forest National Park is the last remaining home for Asiatic or Persian lions. It also has a large number of marsh crocodiles, leopards and wildlife tourists.

The delicate coexistence: Lions, people, and pastoral life in and around Gir

Sasan Gir has a lion-sized dilemma: too many big cats, too little room, only about 10% of the lion population resides in the human-free Gir National Park, 62% of lion population resides in the Gir Sanctuary (with Maldhari settlements) while 22% of the adult lion population resides in the human-dominated agro-pastoral landscape of Saurashtra.

Jhala, explains in Asiatic Lion: Ecology, Economics, and Politics of Conservation: As lion numbers grow, their range now stretches well beyond the park into farmlands and villages across the Saurashtra region.

Maldhari: mal (animal stock) dhari (keeper)

The success story of the Asiatic lion is not one of wilderness untouched – it’s a tale of complex coexistence with humans. At the heart of this are the Maldharis, semi-nomadic pastoralists who have lived in the Gir forest for generations.

The Maldharis value nature deeply, are primarily vegetarian, and raise livestock mainly for dairy production rather than meat. They raise and breed Banni buffaloes (Sindhi buffalo), Kankrej cattle (Sindhi cows), horses, camels, sheep, and goats.

Unproductive or dead cattle is offered up to nature, becoming food for lions and other wildlife. In this way, lions benefit from scavenging and occasional predation.

Local belief systems play a role in tolerance: missing cattle are often seen as “prasad” – divine offerings – symbolizing a form of spiritual “taxation” for living amid predators.

Rarely prized productive livestock are killed by lions due to the husbandry practice of stall feeding and corralling in thorn boma (enclosure) during the night. By grazing livestock during the daytime and avoiding the peak lion activity period, expert herdsman can prevent animals from being lifted by lions.

Yet, Maldhari people persecute lions to deter them from attacking their stock with sling shots, axes, and staffs.

This fragile harmony rests on a foundation of strict wildlife protection laws, timely compensation for livestock losses, and relatively low levels of conflict between humans and lions.

Attacks on humans by lions are rare and mostly accidental: lions rarely stalk or target humans as prey, but usually assault in self-defense or when spooked.

Wildlife authorities swiftly remove problematic lions to prevent conflicts and ensure the safety of both humans and livestock.

Studies have found that tribesmen from Maldhari and other communities living inside Gir earn up to 76% more profit than herders outside, due in part to free access to forest resources and economic benefits from tourism.

Collection of fuel wood and forest products, use of forest topsoil mixed with dung sold as manure, free access to water, job opportunities with the forest department and maintaining their social customs are the lifeline of the Maldharis.

Lions, in turn, earn their keep outside of the Gir National park: they help control crop-raiding animals like nilgai and wild boar, which has led farmers to see them as useful pest managers.

But lion–human coexistence in this densely populated landscape is fragile. Five state highways pass through the Gir forest, there is a widespread limestone mining and a cement plant nearby. With lion numbers rising and their range expanding across Saurashtra, social tolerance may be nearing its limits.

Lion mortality has been observed in the periphery of Gir due to falling in open irrigation wells, electrocution by live wires deployed illegally to prevent crop damage, and poaching.

The state government has taken various steps to prevent unnatural deaths of big cats, measures include:

- building speed-breakers and installing signboards on roads passing through sanctuary areas,

- regular foot patrolling in forests,

- building parapet walls for open wells near forests,

- putting up fences on both sides of the railway track near the Gir Wildlife Sanctuary and

- radio-collaring Asiatic lions to track their movement.

- Also, veterinary doctors and an ambulance service for timely intervention and treatment of lions and other wild animals has been installed.

Lions are a powerful figure in Maldhari folklore and culture.

Lion shrines, or Vaghdev shrines, are common in Maldhari grazing lands, where offerings are made to honour the lions and seek protection for the herds.

Lions are no longer just seen as divine beings – they’re increasingly tied to economic interests. And cultural shifts are slowly replacing reverence with pragmatism.

Nearby, the Siddis, descendants of African communities that settled in India over 800 years ago, also coexist with Gir’s wildlife. Like the Maldharis, they share space and a sense of harmony with the lions.

The lions have become a symbol of pride and prosperity, bringing in tourism and employment to the region.

After losing their title as India’s national animal in 1973 to the tiger, lions became a state symbol of Gujarat. Their resurgence has been widely credited to local pride and conservation efforts—making Gir perhaps the only place in the world where large carnivores thrive amid dense human settlements, not in spite of them.

The future of sustainable carnivore conservation will depend on whether this carefully negotiated peace between human and beast can hold.

The sacred lion in Hindu mythology and history

Lions feature prominently in Mughal history and are associated with deities, royals, and epic stories. Their symbolism extends to various aspects of Indian heritage, like mythology, folklore, and art, as well as religious and ethnomedicinal practices.

India, the only country outside of Africa where lions still live free in their habitat, provides a long record of the dealings between lions and humans. Lions feature prominently in Brahmanism, Vishna, Shaiva, Shakta, Jaina, and Buddhist thought.

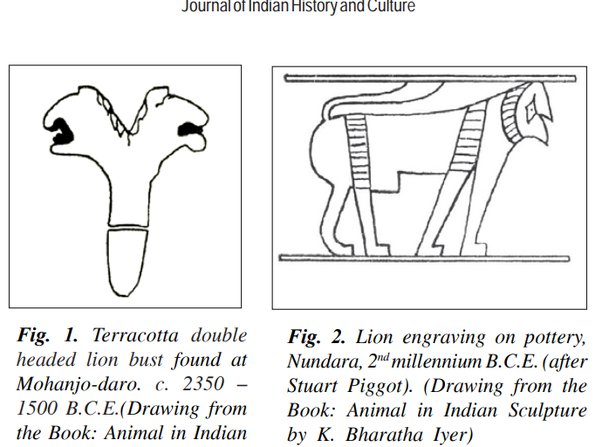

Earliest evidence of lions in India

Badam, G.L. explains, in: Journal of the Palaeontological Society of India, Vol.58(1), P.93-114. 2013; There is one report of a fossil lion (Panthera cf. leo) found in the Bankura district of West Bengal among Pleistocene (2.58 million to 11,700 years ago) deposits.

Apart from this find, there is only one other record of an upper premolar and limb bones of a doubtful panther, either tiger or lion, from the Pleistocene deposits of the Kurnool caves in Andhra Pradesh.

The presence of Neolithic/Chalcolithic cave paintings of lions in Bhimbetka rock shelters of central India (30000–100000 BC) suggest, lions to be early entrants into India.

Indus civilization (3000 BC) shows the most startling depictions of a variety of fauna are from the Indus seals.

But only few records of leonine species have been found.

The earliest depiction of the lion, as far as is known, occurs in the pottery of Nundara, and there is, however, one terracotta of two lion heads from Mohanjo-daro.

Lions were prominent in Persia in the 1st millennium BC, and by the time of the Mauryas (4th century BC), the animal assumed sufficient importance in India to take center stage in Mauryan monumental art, like with the Lion Capital of Ashoka.

Lions are at the heart of India’s national emblem

When the Mauryan emperor Asoka (ca. 304–232 BC) embraced Buddhism and began to emphasize nonviolence, the lion became an emblem of royal strength rather than a symbolic object of royal domination.

After the bloody conquest of Kalinga which claimed more than 100000 lives, a deeply distraught Ashoka found solace in the teachings of Buddha.

Ashoka’s administration became known for its strong ideals of social justice, compassion , non-violence and tolerance ; he instated a legal code based on Buddha’s teachings and had these inscribed on columns erected all across his kingdom.

These edicts (inscriptions on pillars, boulders and even cave walls) focused on social and moral codes that were part of Buddhist beliefs.

The Lion Capital was erected by Emperor Ashoka to mark the spot where Buddha first proclaimed his gospel of peace and emancipation to the four quarters of the universe.

The National Emblem of India is derived from the Lion of Sarnath, near Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh.

The pillar capitals of Emperor Ashoka, found all over northern and eastern India and in the border areas of Nepal, were topped by four majestic lions or bulls seated back to back, carrying a large wheel, the wheel of dharma.

GODL, edited.

In Buddhist texts, there is a strong connection between Siddhartha and the lion: the Lion’s Roar is a powerful metaphor used to describe Buddha’s teaching.

Just as a lion roars to assert its dominance, the Buddha’s teachings (or Dharma) are seen as a fearless declaration of ultimate truth and a call to liberation for all beings.

The national emblem is thus symbolic of contemporary India’s reaffirmation of its ancient commitment to world peace and goodwill. The four lions (one hidden from view ) – symbolizing power, courage, and confidence, – rest on a circular abacus.

The abacus is girded by four smaller animals – Guardians of the Four Directions: The Lion of the North, the Horse of the West, the Bull of the South and the Elephant of the East.

In early Buddhist architecture, the lion, along with the horse, the elephant, and the zebu, was considered auspicious. All these animals appeared as a standard quartet on many Mauryan pillars.

The motto ‘सत्यमेव जयते’, ‘Satyameva Jayate’ inscribed below the emblem in Devanagari script means

‘truth alone triumphs’.

Lions have been India’s national animal when the Gujarat Natural History Society in 1948 had compelled Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru to declare the Asiatic lion as the national animal. In a meeting of the Indian Board for Wildlife, the tiger was declared the National Animal of India in 1972.

Nevertheless, the “Make in India” logo from 2014 is a lion, derived from India’s national emblem. The wheel denotes peaceful progress and dynamism – a sign from India’s enlightened past, pointing the way to a vibrant future.

The prowling lion stands for strength, courage, tenacity and wisdom- values that are every bit as Indian today as they have ever been.

The Vedic Lion of Brahmanism

The mythic origins of the Brahmins date back to the Aryan conquest of India around 1500 BC, but the Ṛig-Veda was recorded around 600 BC.

Brahmanism revived in the time of Gupta rule in India. In the Ṛig -Veda, the lion (simha in Sanskrit) was compared to a god, for the lion is described as

simho na bhimah – frightful as a lion.

The lion’s roar was regarded with awe. The verb used since the Ṛig -Veda for the roar is

nad or stan – to thunder, to roar.

The Maruts (the winds) are recorded as “roaring like lions” (simha iva nanandati).

Or a “lion’s roars” are heard from the clouds in the sky (simhasya stanathah). The compound word simhanada “lion’s roar” is also used.

Maruts are seen as the attendants of Rudra, rather than Indra.Rig-Veda -Mandala 2- Sukta 33- Mantra -11 .

स्तुहि श्रुतं गर्तसदं युवानं मृगं न भीममुपहत्नुमुग्रम |

मृळा जरित्रे रुद्र स्तवानोsन्यं ते अस्मन्नि वपन्तु सेना

…Fierce like young lion : Rudra propitiated by praise. Grant happiness to him who praise (thee) and let thy host destroy him who is our adversary.

Western translators in their translation like Griffith and H.H. Wilson are not using the word lion but simply are saying wild beast. The meaning of word Mṛga (मृग) refers to “wild animals” such as the lion, tiger or deer in vedas. Most of the Indian translators are specifically mentioning the word lion.

Indra इन्द्र : On the mythical creation of the lion in India

Shatapatha Brahmana has two stories of the origin of the lion, writes Karabi Kanungo in her Thesis: “A case study of lion in Indian art up to 6th century“.

According to one creation story, God Indra (Hindu texts, such as the Vedas, the Epics, and Puranas, use Indra, Sakra and Vasava interchangeably) emitted soma (an unidentified plant the juice of which was a fundamental offering of the Vedic sacrifices) out of his nose and it became a lion.

The other story tells us that when Indra drank the soma at the sacrifice, his vital power came out of his body, and his blood became a lion, the ruler of all wild beasts.

The Lion sprang from Indras Nose

From Kanda V, adhyaya 5, brahmana 4

Indra thought within himself: ‘There now, they are excluding me from Soma!’

and even uninvited he consumed what pure (Soma) there was in the tub, as the stronger (would consume the food) of the weaker. But it hurt him:

it flowed in all directions from (the openings of) his vital airs; only from his mouth it did not flow. Hence there was an atonement; but had it flown also from his mouth, then indeed there would have been no atonement […]

From what flowed from the nose a lion sprang; and from what flowed from the ears a wolf sprang; and from what flowed from the lower opening wild beasts sprang, with the tiger as their foremost; and what flowed from the upper opening that was the foaming spirit (parisrut). And thrice he spit out: thence were produced the (fruits called) ‘kuvala, karkandhu, or badara.’ He (Indra) became emptied out of everything, for Soma is everything.

The Lion came to be from the blood of Indra

THE SAUTRĀMAṆĪ Kanda XII, adhyaya 7, brahmana 1

Indra slew Tvaṣṭṛ’s son, Viśvarūpa. Seeing his son slain, Tvaṣṭṛ exorcized him (Indra), and brought Soma juice suitable for witchery, and withheld from Indra. Indra by force drank off his Soma-juice, thereby committing a desecration of the sacrifice. He went asunder in every direction, and his energy, or vital power, flowed away from every limb.

2. From his eyes his fiery spirit flowed, and became that grey (smoke-coloured) animal, the he-goat; and what (flowed) from his eyelashes became wheat, and what (flowed) from his tears became the kuvala-fruit.

3. From his nostrils his vital power flowed, and became that animal, the ram; and what (flowed) from the phlegm became the Indra-grain, and what moisture there was that became the badara-fruit.

4. From his mouth his strength flowed, it became that animal, the bull; and what foam there was became barley, and what moisture there was became the karkandhu-fruit.

5. From his ear his glory flowed, and became the one-hoofed animals, the horse, mule, and ass.

6. From the breasts his bright (vital) sap flowed, and became milk, the light of cattle; from the heart in his breast his courage flowed, and became the talon-slaying eagle, the king of birds.

7. From his navel his life-breath flowed, and became lead,–not iron, nor silver; from his seed his form flowed, and became gold; from his generative organ his essence flowed, and became parisrut (raw fiery liquor); from his hips his fire flowed, and became surd (matured liquor), the essence of food.

8. From his urine his vigour flowed, and became the wolf, the impetuous rush of wild beasts; from the contents of his intestines his fury flowed, and became the tiger, the king of wild beasts; from his blood his might flowed, and became the lion, the ruler of wild beasts.

9. From his hair his thought flowed, and became millet; from his skin his honour flowed, and became the aśvattha tree (ficus religiosa); from his flesh his force flowed, and became the udumbara tree (ficus glomerata); from his bones his sweet drink flowed, and became the nyagrodha tree (ficus indica); from his marrow his drink, the Soma juice, flowed, and became rice: in this way his energies, or vital powers, went from him.

From: Burgess, Jas. Indian Antiquary: A Journal of Oriental Research, Vol.5, Popular Pakistan, P.40. 1971.

The lion in the Indian culture of Vaishnavism

The stages by which Vishnu rose to become a major deity are lost in the distant past, but some clues remain. Vaishnavism, has its origins in the pre-Gupta period (185 BC-319).

The rise and growth of Vaishnavism was closely connected with that of Bhagavatism. Vishnu was a minor god in Vedic times. He represented the sun and also the fertility cult called Surya Narayana (in Vaishnavite interpretations of the Rig Veda).

By the second century BC he was merged with Narayana, a non-Vedic tribal god called bhagavata, and his worshippers were called bhagavatas.

The lion iconography of the Gupta Empire

The Gupta Empire (c. 319–550 CE) covered most of the Indian subcontinent. Chandragupta I, Samudragupta, Chandragupta II and Skandagupta were some of its mightiest emperors. On their gold coins they show roaring lions and Lion-slayer scenes.

Historian R. C. Majumdar theorizes that Chandragupta’s conquest of present-day Gujarat may have presented him with an opportunity to hunt lions, resulting in the substitution of tiger with lion on the imperial coins.

When Samudragupta occupied the valley of the Ganges with its forested areas, the abode of the Bengal tiger, he issued tiger-slayer coins. Similarly, Chandragupta Vikramaditya II commemorated his victory over Malwa and Saurashtra or modern Kathiawad (the habitat of lions) by issuing lion-slayer coins.

Pushkar Sohoni, tells us, in: Old fights, new meanings: Lions and elephants in combat:

The image of the lion ( or tiger) as an animal hunted by a king and also as a personification of royal power itself was consolidated under the Gupta dynasty.

Though there are occasional examples of lion hunts of earlier date, such as a Shunga-period sculpture at Sanchi (second century BC), it was under the Gupta dynasty that the lion and the sun became prominent symbols of royalty.

Chandragupta II (r. ca. 375–414 CE) issued gold coins that depicted him hunting a lion and bore the legend Simhavikrama, which can be translated as “valorous among lions.”

As his royal title was Vikramaditya (literally “the valorous sun”), several congruous representations of royalty (both literary and visual) were conflated: poets and artists often compared the sun, with its halo of flares, with the form of a golden lion with its mane.

The contemporaneous Sasanians, with whom the Guptas had contact, valorized the lion hunt as a marker of kingship and power.

Their coins and metal ware regularly depicted such hunts. The narrative representations of the Sassanian art often feature figures shown in the profile or a three-quarter view.

This image depicts King Hormizd II or King Hormizd III hunting lions in Iran during the Sasanian Empire between 400 and 600 CE.

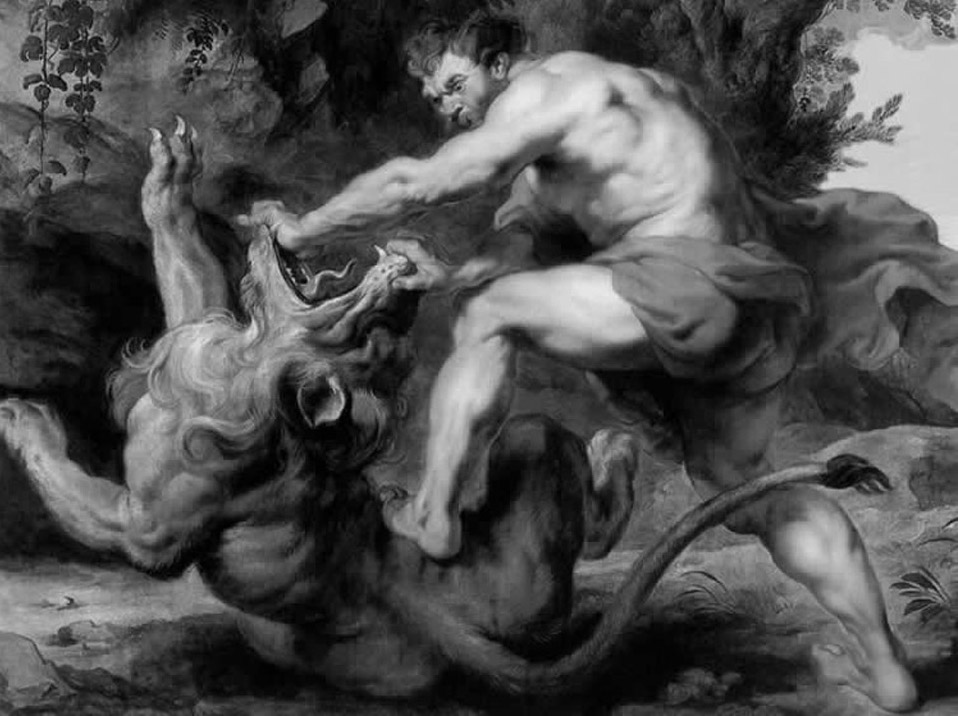

The animal-slayer motif was popular in the art traditions of the Sumerians (4100 to 1750 BC) , Hittites (1650 to 1200 BC), Greeks (1200 to 323 BC), Persians (550 to 330 BC) and others. Mostly the lion, and to a certain extent the tiger is present where this beasts did roam.

This motif, prevalent across various cultures and time periods, symbolizes power, control, and sometimes, the taming of wild nature. A vast diversity of animals are depict in fighting scenes, like wolves, bulls and bears or even dragons.

Narasimha नृसिंह

The Rig Veda identifies Bhaga, the lord of bounty, with Varona and later with Vishnu, and the Brahmanas identify Vishnu with the personified sacrifice and with the cosmic man whose sacrificial dismemberment gave rise to the universe.

The theory of incarnation greatly facilitated the assimilation of popular divinities into Vaishnavism.

The Bhagavata is a theistic devotional cult based mainly on the Bhagavad Gita, but later the Bhagavata Purana and Vishnu Purana became its main texts.

Vishnu has ten avatars, or incarnations: fish, tortoise, boar, man-lion, dwarf, Rama the Ax Wielder, Rama of the Ramayana, Krishna, the Buddha, and Kalki.

The Bhagavata Purana articulated the views of tenth-century South India and of those worshipers of Krishna known as the Bhagavatas.

Glory to you, O Lord of the universe,

Who took the form of a Man-Lion;

As easily as you would crush a wasp with your fingers,

You tore apart the demon Hiranyakashipu,

With the sharp nails of your bare hands,

Which are as beautiful as the lotus flower.

Gita Govinda of Jayadeva

The Bhagavata Purana should be given as a gift on the full moon day of Proshthapada (September), along with an image of a golden lion.

In Hinduism नरसिंह Narasimhas sculptures and stories are dated as early as 300 BC., thus making him one of the oldest representations of a God as lion.

Narasimha, the fourth incarnation of Lord Vishnu was half-man (Nara) and half-lion (Simha). He killed a demon named Hiranyakashipu.

After the death of Hiranyaksha, who appears in the boar incarnation of Vishnu, his brother Hiranyakashipu swore to avenge his death. By performing severe austerities, he obtained a powerful boon from Lord Brahma the Creator:

that neither man nor animal could kill him,

not at night or in the day,

not on earth, sky or water,

neither inside nor outside and

with neither weapon nor fire or water.

This made the demon so powerful that he became arrogant, savage and cruel, ruling the earth with brutality and terror. He challenged the gods themselves and proclaimed himself to be divine.

But the demon’s son Prahlada was a devout worshiper of Lord Vishnu, a devotion the demon could not accept. He tried to change his son’s views by cajolement, threats, and even, by trying to kill him. But Prahlada was undaunted, for he knew that Vishnu would save his devotee.

Finally, Hiranyakashipu asked Prahlada where his beloved Vishnu was. Prahlada answered: ‘everywhere’.

Then the demon kicked a pillar and asked whether Vishnu lived in the pillar. Suddenly, Narasimha, a lion-faced man – neither man nor animal – sprang out of the pillar and a terrible fight ensued.

Narasimha fought the wicked demon all the way to the front door – neither inside nor outside the house. As the sun was setting – it was neither day nor night – Narasimha killed the wicked demon with his claws – not a weapon nor fire or water.

Thus the wicked demon was destroyed without Brahma’s boon being violated.

The story of Narasimha serves to teach the devotee that the Lord is everywhere and always comes to the help of believers.

Narasimha is especially popular in Andhra Pradesh, Orissa, and Karnataka. Ahobalam is the site of the temple of Roudra (angry) Narasimha, where the mythic pillar from which he emerged and the lake in which he washed his hands after killing Hiranyakashipu are situated.

At Simhachalam (near Visakhapatnam) is the temple of Narasimha built by his devotee Prahlada, who was king of the east. The Jeers (religious leaders) of the Vaishnava sect are called Alagiya Singhar (Beautiful Lion), after Narasimha whom they worship.

Narasimha was worshiped by the Vijayanagara kings and an enormous figure dominates the ancient city of Vijayanagara (present-day Hampi).

This image of Lakshmi-Narasimha (or Ugranarasimha, meaning the terrifying Narasimha) was carved in situ out of a single rock. According to an inscription found there, it was created in 1528 CE during the rule of Krishnadevaraya. The icon originally had a small image of Lakshmi sitting on his lap.

Beside the Hampi temples, important ancient and medieval archeological sites with Narasimha icons are found as Vaikuntha Chaturmurti (four-headed aspect of the Hindu god Vishnu) in Nepal, Kashmir and Khajuraho temples.

One faced versions are found in Garhwa and Mathura (Uttar Pradesh) and in Ellora Caves (Maharashtra).

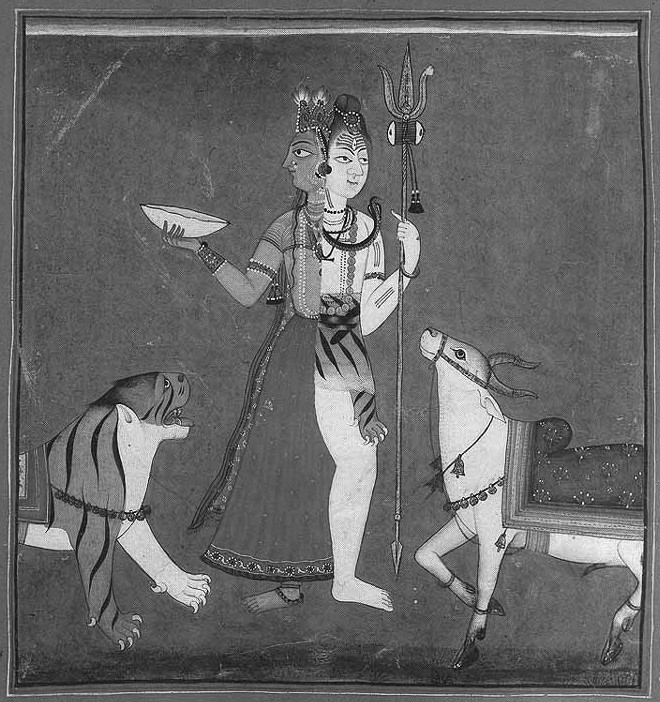

The lion-faced goddess – Narasiṁhi

This Great mothers’ imagery is at times anthropomorphic – having a lion, tiger, hyena, elephant face and the body of a woman.

Devi is also popularly known as Goddess प्रत्यङ्गिरा Pratyangira, other names are Atharvana Bhadrakali and Simhamukhi and she rides a tiger.

Narasimhi is an incarnation of the Mother Goddess that is associated with the Narasimha avatar of Hindu God Vishnu.

The Vaishnava school of thought suggests that Goddess Narasimhi appeared from Goddess Lakshmi to keep in control Narasimha, whose fury was about to engulf the universe.

The Shaivite school of thought suggests that Goddess Narasimhi is an incarnation of Goddess Shakti शक्ति (“power” or “energy”).

She appeared from the wings of Sharabha – the form Shiva took to subdue the anger of Narasimha.

In Tibetan and Bön Buddhism there is a lion-faced dakini (goddess) of the Dzogchen or atiyoga tradition.

The similar Hindu deity is known as Narasimhi, and the Tibetan Buddhist form is called

- Siṃhamukhā in Sanskrit and

- Senge Dongma (Wylie seng ge gdong ma) in Tibetan.

“Lion-face Dakini” literally can mean the wisdom that “illuminates the darkest corners.”

She is represented as a fierce dakini, with the head of a snow lion, her mouth is depicted with a roar, symbolizing untamed fury and jubilant laughter.

This deity is considered to be especially effective for dispelling black magic, curses, obstacles and harm-doers.

“Arising from the state of the dharmadhatu, Mother of all conquerors, Queen of all the countless dakinis;

With magic powers smashing to dust hindrances and enemies.

Homage to Simhamukha.”

Nyingma liturgical verse

The Tibetan Snow Lion (Tibetan: གངས་སེང་གེ་; Wylie: gangs seng ge) is a mythical animal of Tibet. The lion symbolizes fearlessness, unconditional cheerfulness and the element of Earth.

It is said to range over mountains, and is commonly pictured as being white with a turquoise mane. Two snow lions appear on the flag of Tibet.

Lions represent more than ferocious power. They literally represent Buddha Dharma. The “Lion’s Roar” is synonymous with awakening to the Dharma.

Mahadevi महादेवी: The lion in the Indian culture of Shaktaism

The worship of Mother Goddess or Mahadevi महादेवी (Great Goddess) has been present in India since the period of the Indus Valley Civilization.

Two felines (tigers?) and the mother- goddess are found on an oblong terracotta seal unearthed at Harappa.

It represents a nude female figure shown upside down with legs wide apart and with a plant issuing from her womb. At the left corner of the seal there are two figures of rampant tiger facing each other, which according to scholars are two genii (animal ministrants) of mother-earth.

The terracotta sealing found at Nalanda depicts an eight-armed goddess riding a lion in the upper register.

The devi is shown with attributes like a sword, shield, chakra, bow, and bell.

This appears to be one of the more elaborate forms of Durga. The lower register has a inscription in Brahmi of 600-700 and reads “Ghrtanjana-Grama-Janapadasya” (Ghenjan in Gaya district).

Hiralal Shastri (who reads it as ‘Ghananjana’) identifies it with the village of Ghenjan in Gaya district which has yielded many Hindu and Buddhist antiquities.

Later coins from the Gupta period suggest a further nuance to the goddess’s identity, as does Durga iconography today.

Here she is seated on a lion, holding a cornucopia and a diadem. The lion mount is viewed as a symbol of Devī’s power (shakti).

Gupta art is regarded as the high point of classical Indian art, and the coinage is equally regarded as among the most elaborate of ancient India.

Ambika अम्बिका

In Shaktism, Ambika is revered as Adi Parashakti, the mother of the universe and all beings; she is riding a lion. Parashakti is often identified with various incarnations such as Chandi, Durga, Bhagavati, Lalitambika, Bhavani, and many others.

According to the Devi Mahatmya, after the asura Mahishasura was slain by Durga, the divinities embarked on a pilgrimage to the Himalayas and sang a hymn of praise in honor of the supreme goddess.

Meanwhile, Goddess Parvati had come to the source of the Ganges to bathe and observed the hymn. She asked the divinities to whom the hymn was dedicated. Before they could respond, she shed her outer corporeal form, revealing her true and auspicious form, who is then named Ambika.

In Puranic Hinduism, Shiva and Shakti are the masculine and feminine principles that are complementary to each other. Shakti is also conceived of either as the paramount goddess or as the consort or mother of a male deity.

Like wife and husband, as for Parvati with Shiva in Shaivism, Saraswati with Brahma in Brahmanism, Lakshmi with Vishnu, Sita with Rama, and Radha with Krishna in Vaishnavism.

Ambika in Jain religion

The earliest reference to Ambika, is obtained in the Jain writings (Vrtti of Jinabhadraganin Ksamasramana on his Vises dvasyaka-bhdsya).

In Jain iconography, Ambika is often shown with four arms standing or seated under a mango tree, or with a bunch of mangoes hanging over her. She holds a child in her lap, and a lion sits at her feet .

Ambika is said to have been an ordinary woman named Agnila who became a Goddess. Her husband was born as a lion, which she rode as her mount. The two sons of her are initiated by Neminātha.

According to Jaina mythology , Neminatha, also known as Aristanemi, twenty second Tīrthankara (spiritual teachers) , was the cousin of Krishna, the Puranic hero and Hindu deity who is referred in also as Hari , Govinda and Vishnu.

The lion is also connected to Mahāvira, Siddhayika Devi and Mahamanasi Devi.

Jain myth: Kesari Sinh

In her first dream queen Trishala saw a magnificent lion descending towards her and entering her mouth. This dream indicates that her son will be as powerful and strong as lion. He will be fearless, almighty, and capable of ruling over the world[…]

Also in Jainism, lions are symbolic of strength, courage, and spiritual majesty, and seen as guardians, protectors, or symbols of royalty and fearlessness.

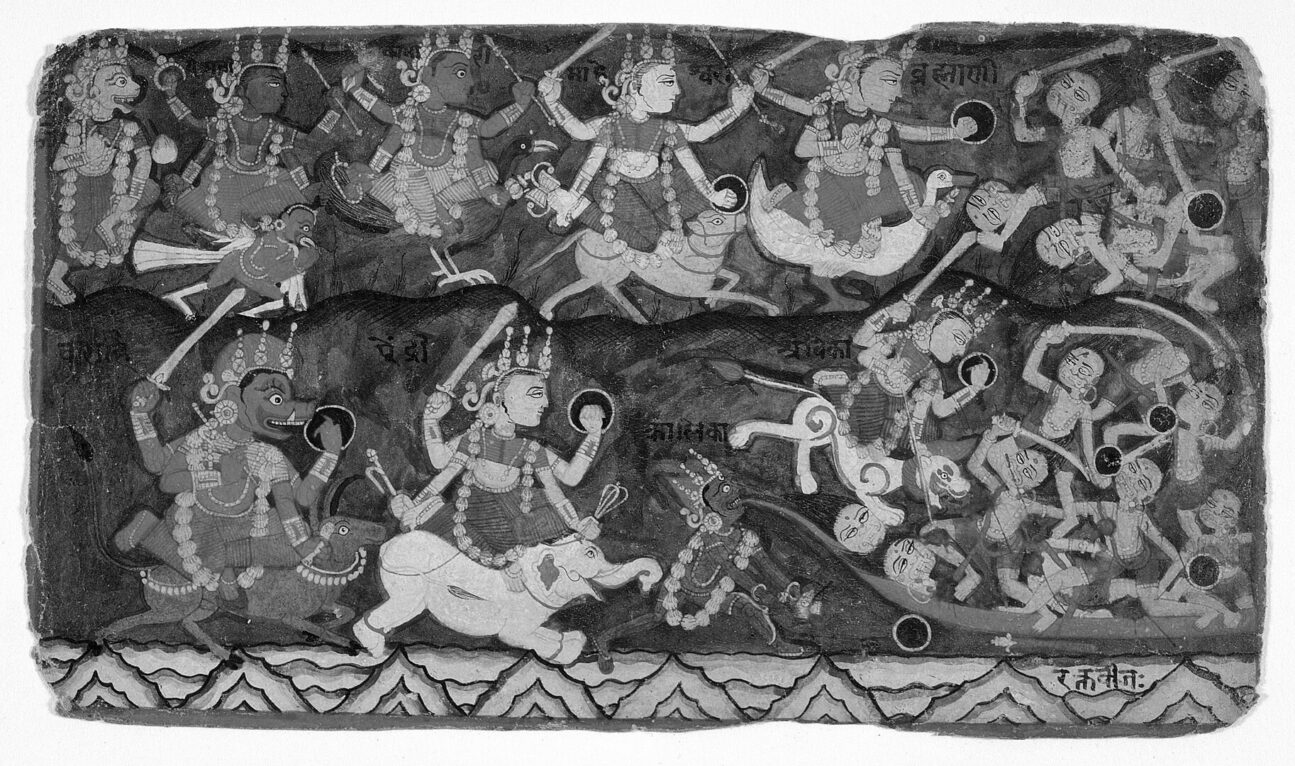

Sapta Matrikas मातृका

Goddess Narasimhi or Pratyangira is one of the Sapta Matrikas मातृका, the seven Mothers of Tantric religion. For some scholars the concept of Matrikas as powerful goddesses emerged in the early 1st millennium BC, and possibly much earlier.

Worship dedicated to Pratyangira is still performed for the welfare of the people and for eliminating the influences of evil forces.

Temples dedicated to Pratyangira Devi, such as those in Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, conduct fire rituals ( होम homa) that invoke her energy to dispel malevolent forces. She is generally propitiated by the sacrifice of fowl.

Pratyangira is sometimes depicted as a lion-headed goddess, riding a chariot drawn by lions, symbolizing her ability to devour all negative forces.

In India, with Tantrism, the composite concept of mother goddesses like Narasiṁhi, Simhasya (the lion-faced goddess), Vagalamukhi (the cat-faced goddess), and Varahi (the boar-faced goddess) emerged. The Matrikas are goddesses of the battlefield, numbering seven, eight or ten.

Durga दुर्गा: The lion in the Indian culture of Shaivism

Durga is a common name for the Goddess. She has a large following in Hinduism and often the title Durga is an umbrella name covering a wide assortment of goddesses across India.

Worship of the female principle took on dramatic new dimensions in India in the fifth and sixth centuries. Images of the Hindu goddess Durga killing the buffalo demon Mahishasura appeared across the country. In caves and temples, in metal and stone, artists captured the ferocious, protective energy of the goddess as revealed in her heroic victory.

Even when she is depicted in battle, the goddess appears calm and exceedingly beautiful, suggesting powers so great that they far exceed the threat.

The lion is a vahana (vehicle) of the goddess Durga दुर्गा , representing her ferocious and protective aspects, her name is Sherawali (one who rides on a lion).

She is worshiped as a principal aspect of the mother goddess Mahadevi. This form of Parvati is associated with protection, strength, motherhood, destruction, and wars.

In Shakta-Shaiva traditions, Shiva’s association with the lion is tied to his consort, Durga.

While Durga rides a lion or tiger into battle, Shiva is the observer, reinforcing the complementary nature of their divine roles.

In most accounts it is Himvat (the personification of the Himalayan mountains), her father, that gave Durga a golden lion to ride into battle.

The golden skinned hairy lion is an archetypal symbol for the golden rayed sun, the lord of the day, whose appearance kills the god of the night.

It is the Skanda Purana, where Shiva, pleased with Parvati’s devotion, blesses her with a lion as her eternal companion. The lion, in this context, represents divine power under control, reinforcing the unity of Shiva and Shakti, or Shakta Ardhanarishvara अर्धनारीश्वर.

Durga Puja

Durga Puja (or the Durgotsava or the Sharadotsav) is the annual Hindu festival that celebrates Goddess Durga’s victory over Mahishasura and epitomizes the victory of Good over Evil. Durga Puja is mostly celebrated in the eastern states of India, like West Bengal, Jharkhand and Assam and coincides with Navaratri and Dussehra celebrations observed by other traditions of Hinduism.

Navratri (‘Nav’ means nine and ‘ratri’ means night ) therfore, it is celebrated over a period of nine nights. During Navratri, people from Western India (Gujarat and Maharashtra) and North India worship the nine avatars of Goddess Durga.

In Nepal, Navratri is called Dashain, it is one of the most significant festivals of the year and lasts for 15 days.

They honour the nine forms of Devi Durga, with each day symbolizing a different form of the goddess.

1) Shaila putri शैलपुी – Devi of the mountains, representing purity and devotion.

2) Brahmacharini चारणी – Devi of austerity and penance, embodying self-discipline.

3) Chandraghanta चघटा – Devi of courage and strength, symbolizing fearlessness. She is therfor riding a tiger.

4) Kushmanda कुमाडा – Devi of creation, associated with prosperity and energy. She is therfor riding a tiger.

5) Skandamata कदमाता on lion – Devi of motherhood, representing protection and nurturing.

6) Katyayani कायायनी on lion – Devi of valor, signifying the power to overcome adversity.

7) Kalaratri कालराि – Devi of darkness, embodying the removal of ignorance.

8) Mahagauri महागौरी – Devi of purity, symbolizing wisdom and tranquility.

9) Siddhidatri सदाी – Devi of accomplishment, representing the fulfillment of desires.

On day 10 it is Vijaya Dashami – signifies the triumph over the three gunas: Raja (passion), Tamas (ignorance), and Satva (purity).

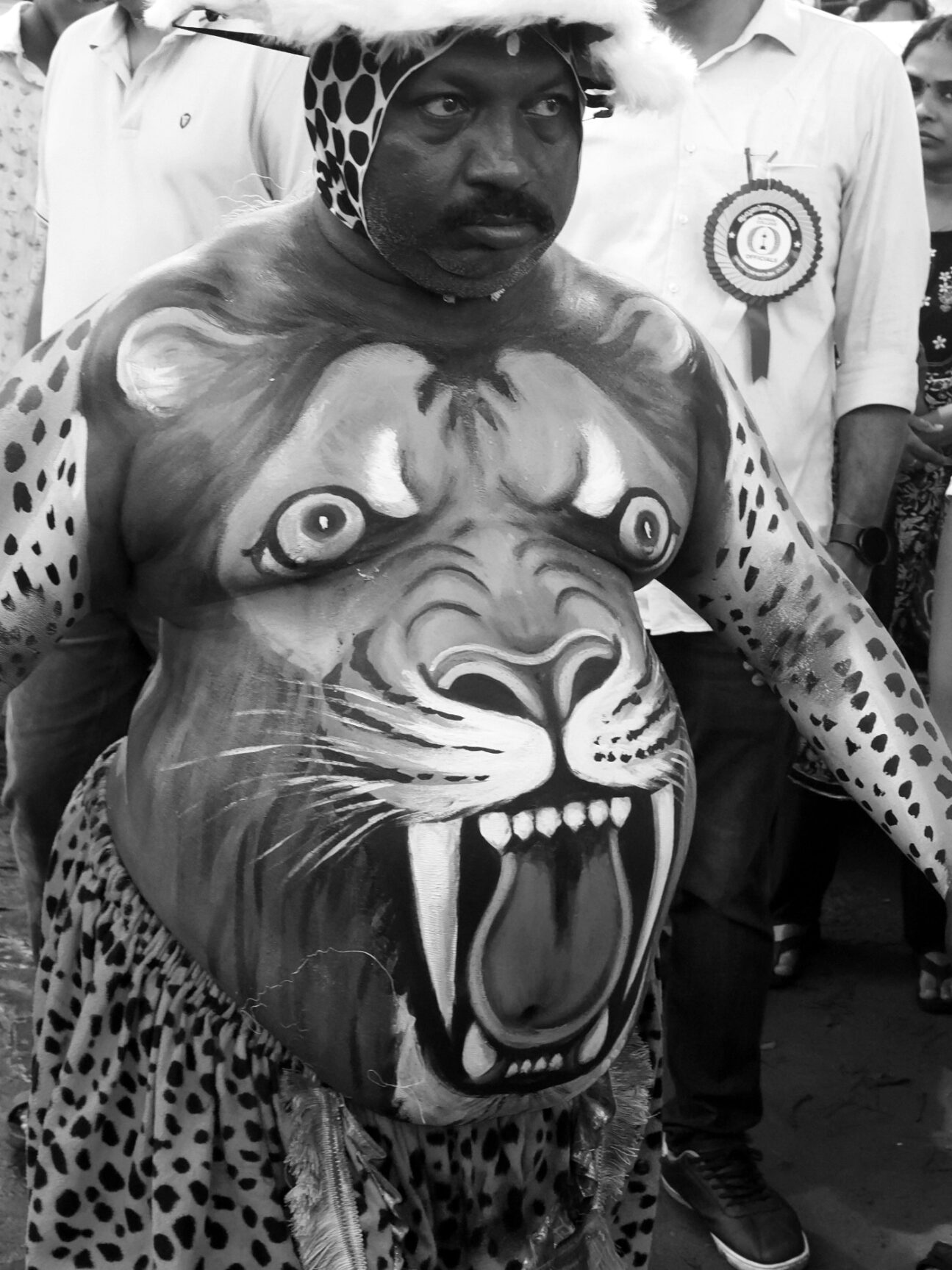

During Dasara, the lions or tigers are associated with the goddess Durgas triumph of good over evil. On these day, the tiger dance is very popular in Mangaluru and in the Dakshina Kannada district of India.

Similarly there is a Tiger dance during Puli kali. This festival of South India celebrates the annual return of the dethroned king of Kerala, Mahabali, in the form of the harvest during Onam (annual harvest and Hindu cultural festival).

Various manifestations of Durga (Mahâdurgâ, Jayadurgâ, Vanadurgâ, Shûlinîdurgâ, Chandikâ, Mahishamardinî) have the lion as their vâhana (mount).

There is no mention of her riding a tiger in any scriptural text (Devîmâhâtmya, Devîbhâgavata Purâna, Kâlikâ Purâna, Mahâbhâgavata Upapurâna, Tripurârahasya, Shâkta sections of Skanda Purâna; Vâmana Purâna; Brahmavaivarta Purâna; Varaha Purâna; Shiva Purana, Lalitopakhâyanam).

Even the Agni Purâna, which describes how to depict deities in icons, states the presence of lion as her vâhana.

As per the Pûrvakhanda of Vâyavîya Samhitâ of Shiva Purâna, the tiger named Somanandî or Dawon is the vâhana of Bhagavatî Pârvatî.

Since many people outside the Shâkta circle assume that the wife of Bhagavâna Shiva and the mother of Bhagavâna Shiva are the same person; the tiger got superimposed over the lion in North India.

Shiva शिव

In Shaivism, the lion is linked with Lord Shiva, symbolizing both his ascetic control over material desires and his dominance over the natural order.

While Shiva is depicted with tigers, which represent his primal power, the lion also plays a role in Shaiva mythology and iconography.

Shiva is shown seated on a lion skin, an image found in both Puranic literature and temple sculptures. According to legend, Shiva slew a lion (or a tiger) that was conjured by a group of sages who sought to test his ascetic power.

Instead of being overpowered, Shiva effortlessly defeated the beast, wearing its skin as a sign of his transcendence over the forces of nature. Mostly Shiva is shown wearing a tiger or leopard skin.

‘Sher’ in Hindi शेर is borrowed from Classical Persian and means big cat. That is why in colloquial Hindi the lion, the tiger and the leopard are all called ‘ Sher’ . To add to the confusion the word ‘Bābar’ appears to be a lengthened form of the word ببر, ‘ babar’ or ‘ bibar’ , and is commonly explained as meaning ‘ tiger.’ In Persian and Hindustani dictionaries the word ببرis rendered both as ‘ lion’ and as ‘ tiger ‘.

Shiva – Sharabha शरभ

Shiva Purana mentions:

After slaying Hiranyakashipu, Narasimha’s wrath threatened the world. At the behest of the gods, Shiva sent Virabhadra to tackle Narasimha. When that failed, Shiva manifested as Sharabha.

Sharabha thus quelled Narasimha’s terrifying rage; he then decapitated and de-skinned Narasimha so Shiva could wear the hide and lion head as a garment. The Linga Purana and the Sharabha Upanishad also mention the mutilation and murder of Narasimha.

Narasimha Purana suggests that Vishnu assumed the form of the ferocious two-headed bird Gandabherunda, who defeated Sharabha.

In another version it is Vishnu as Ashtamukha Gandaberunda Narasimha who is disemboweling and killing Shiva as Sharabha and Hiranyakashipu.

…with nails from His thousand hands caught hold of this Sharaba a form assumed by Rudra and tore open the chest of the Sharaba, using His sharp and deadly nails and killed it in the same manner as He had killed Hiranyakashipu…

Some Vaishnavas regard Sharabha as a name of Vishnu.

One version also mentions that Sharabha, after subduing Narasimha, assumed his original form of a lion, the mount of goddess Durga, and returned to rest at her feet.

Kaal Bhairava भैरव

In some Shaiva traditions, Shiva is identified with Kaal Bhairava, a fearsome deity associated with time, destruction, and protection. Bhairava is sometimes depicted riding a lion, particularly in Tantric traditions where the lion represents the raw, untamed force of Shiva’s cosmic dance of dissolution and regeneration.

The Kaal Bhairava Ashtakam, a sacred hymn dedicated to Bhairava, describes him as riding a mighty beast, his presence striking terror into evil forces. In some regions of Kashmir and Nepal, Bhairava’s lion imagery merges with Buddhist influences, where the lion serves as a symbol of fearlessness and divine wrath.

Pancanana पञ्चान

Shiva is Pancanana (five-faced) because he is the lord of the five elements (air, fire, water, ether, and sky) and corresponding to his five activities (pañcakṛtya):

- creation (sṛṣṭi),

- preservation (sthithi),

- destruction (saṃhāra),

- concealing grace (tirobhāva), and

- revealing grace (anugraha).

The lion is also known as Pancanana because of its wide, gaping mouth and also because this animal is supposed to symbolize the five elements, being the servant of Bhutapati (lord of elements or Shiva ). One of his most important mantras has five syllables: ॐ OM

namaḥ śivāya

Shiva and the lion are also known as Pasupati (lord of beasts ). This identity in the names of Siva and lion has often proved a great temptation to Sanskrit poets to pun on the words Pancanana and Pasupati.

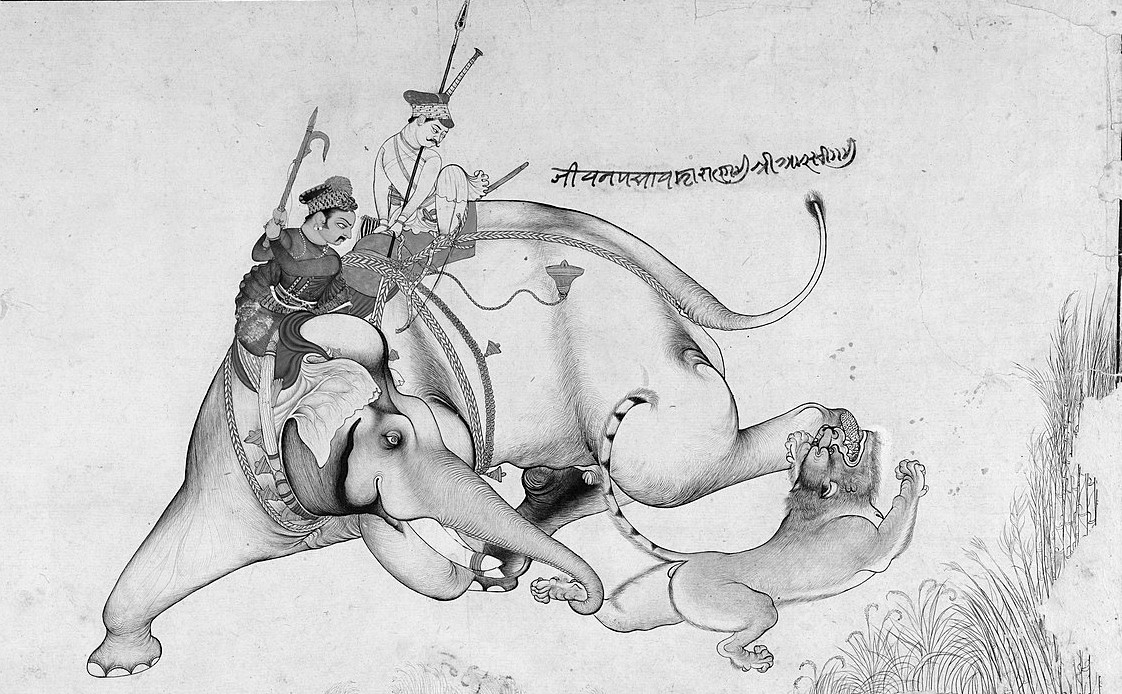

The related term vanaspati, which symbolizes a lion (lord of the jungle) has the same meaning as the Sanskrit word rajavan for king of the jungle, both words find frequent reference in Indian literature, where it figures as the inveterate enemy and vanquisher of the mighty elephant.

Elephant and lion in combat

The conflict is recognizable; innumerable lithic representations have recorded this jungle episode, with its overtones of metaphorical (often political) significance.

The conquering king is the lion and the vanquished elephant is the mighty enemy.

This meaning is carried into other field of human activity, such as learning as when the poet says,

“Victorious is the light (lion) who prowls in the Vedanta jungle,

who lies in the Blue Mountain and who has destroyed the elephant of maya (illusion or ignorance)”.

The elephant is considered a sacred symbol in Buddhism.

At the same time, Buddha himself is visualized as the great lion. Gautam Buddha, the son of the Sakya chieftain (born around 2,500 BC) was known as Sakyasimha after achieving enlightenment.

Lions featured in the ancient Buddhist

texts of the Jatakas (∼2,400 BC) that depict Buddha as various animal incarnations, often as a noble lion.

Both the elephant and the lion are symbols of Jain Tirthankaras (supreme preachers of dharma).

The lion is considered as equally sacred in Hinduism (the lion being the carrier or vehicle of Goddess Durga and Vishnu in his man-lion form, Narasimha).

The elephant is associated with Indra and Ganesha. There are images of Shiva flaying alive an elephant, Gajasura. Shiva is also shown as flaying alive a tiger and a lion.

Makaraveta festival, which occurs on a day after Makar Sankranti, celebrates Gajendra Moksha, the legend of Vishnu saving an elephant devoted to him from a crocodile.

Regardles some political circles define the motiv as dominance of Hinduism over Buddhism, as eastern Ganga rulers were followers of Hinduism.

Pushkar Sohoni, writes, in: Old fights, new meanings: Lions and elephants in combat:

Bharavi, who was active in the sixth century CE, mentioned lions and elephants as metaphorical enemies. In the Kirātārjunı̄ya, Bharavi describes how the lion

“springs at thundering clouds,”

thinking them to be elephants.

The motif of the lion and elephant in combat was widespread across the entire subcontinent by the ninth century CE. New terms, such as gajasimha (“elephant [and] lion”), were designated for depictions of this combat.

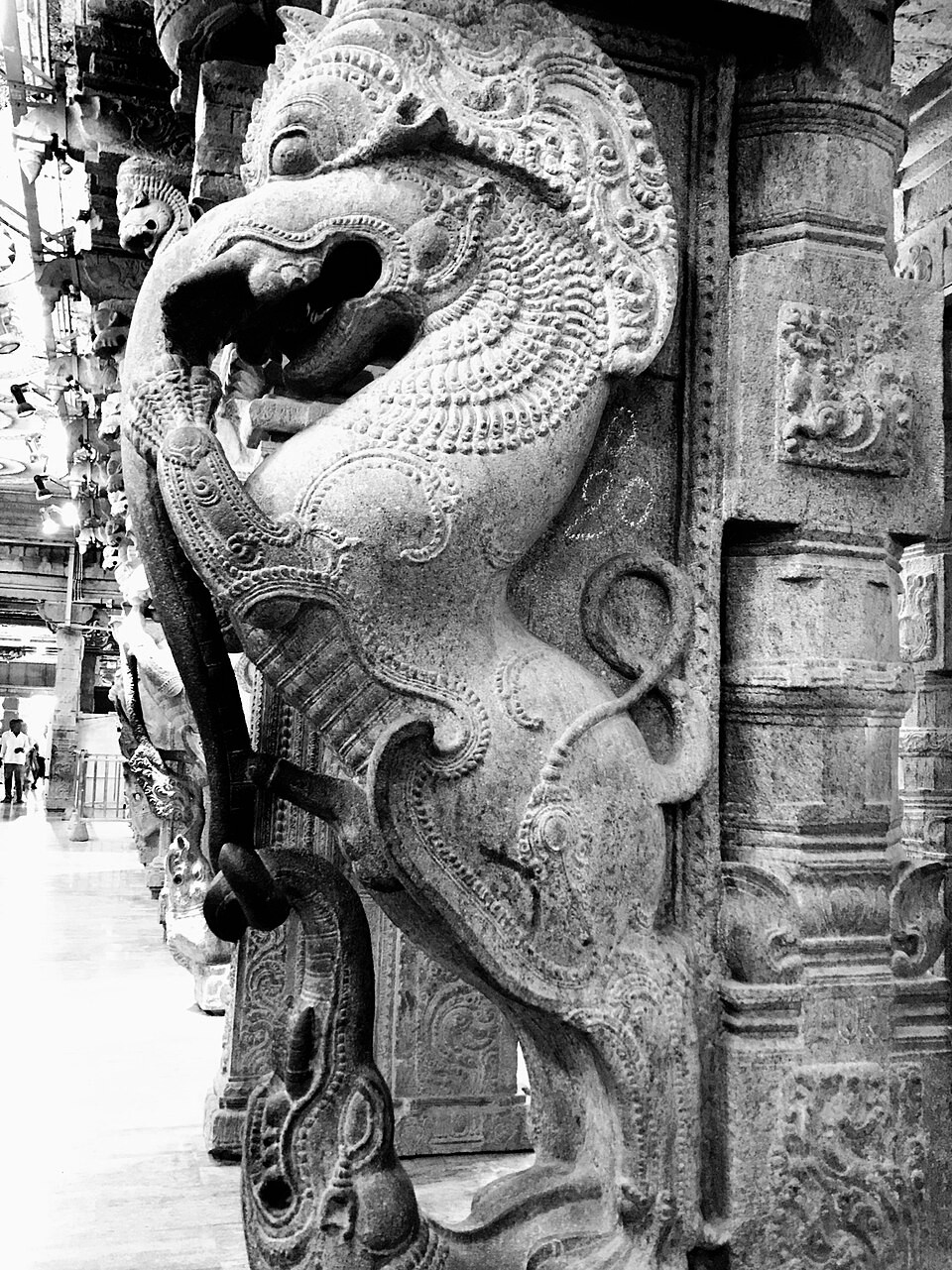

Gajasimha Vyāla व्याल

The term gajasimha Vyāla व्याल refers to a hybrid with a lion’s body and an elephant’s head.

These imaginary beasts occasionally replace or supplement lions in combat with elephants.

Vyala or Vidala in Sanskrit, or Yali, is a mythical creature seen in many Hindu temples, often sculpted onto the pillars.

It may be portrayed as part lion, part elephant, part horse, and part snake.

Also, it has sometimes been described as a leogryph (part lion and part griffin), with some bird-like features.

The vyala is said to be a guardian creature, protecting human beings both physically and spiritually. It is regarded to be a fearless beast, possessing supremacy over the animal world and being more powerful than the lion, the tiger ,or the elephant. It is also believed to be the symbolic representation of man’s struggle with the elemental forces of nature.

The lion and royality

In addition to South Asian religious architecture, the lion and elephant combat also appeared on forts and palaces of the sultanates of the Deccan.

By this period, the vyala had acquired a talismanic function, and all forts in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries bore it, usually on important bastions and entrance gates.

Irrespective of the sectarian affiliation of the rulers, the motif consistently stands for royal conquest and invincibility.

The image of the lion as an animal hunted by a king and also as a personification of royal power itself was consolidated under the Gupta dynasty (coins). In literary and visual representations in the early first millennium CE, the “lion-seat” (siṃhā sana) became an emblem for a royal throne, as in the epic of the Mahabharata.

After the Guptas, the Pallavas continued to use the lion as a symbol of royal power. The Pallava dynasty was revived under the king Simhavisnu, whose name meant “lion-Vishnu” (r. ca. 555–590 CE).

From the eighth century onward, his successors particularly Narasimhavarman II, also known as Rajasimha, or “royal lion” (ca. 700 –728 CE) – patronized cave temples that deployed lions as column supports, brackets for cornices, and decorative elements.

By the tenth century in eastern India, under the Pala dynasty, the lion came to denote spiritual as well as royal power, as evidenced by its use on throne supports for the Buddha.

And by the eleventh century, the lion in combat with a warrior was a common enough trope for royalty that the image of the first Hoysala king Śal̄a slaying a lion became their emblem in South India and the Deccan.

The Hoysala empire is named after a legend from Kannada folklore, which narrates the tale of a brave young man named Sala who courageously defeated a lion to protect his Master Sudatta.

In Kannada language, ‘Hoy, Sala’ translates to ‘Strike Sala’.

At every Hoysala temple, a sculpture of a lion can be found, typically on the śukanāa (the porch above the frontal projection of a temple) and also a warrior slaying a lion.

The royal lion hunt

Control of the natural world, as expressed by fierce animals, was a key aspect of the iconography of kingship. Hunting was one way in which control over the natural world was demonstrated.

The tiger and the lion have in India the same dignity, and are both supreme symbols of royal strength and majesty/ The tiger of men and the lion of men are two expressions equivalent to prince, as the prince is supposed to be the best man.

It is strength that gives victory and superiority in natural relations; therefore the tiger and the lion, called kings of beasts, represent the king in the civic social relations among men. The narasinhas of India was called, in the Middle Ages, the king par excellence.

De Gubernatis Angelo. Zoological Mythology, or, The Legends of Animals, Vol. 1-2. 1872.

Strabo’s first century description of a royal procession in India records among others, pardalis (probably cheetahs) and leontes (lions) walking in it.

The remarkable gold coins of Chandra Gupta II and Kumar Gupta, the Gupta kings of the 4th and 5th centuries have hunts of lions, tigers and rhinos. Lions, elephants and even tigers are writ large in Indian sculpture throughout the county.

Someshwara III, the Chalukya king of Kalyani of the 12th century, lists 35 different methods of hunting deer/ antelope and he goes on to describe 31 of them including coursing blackbuck with cheetahs.

Firoz Shah Tuglaq, who ruled at Delhi in the 14th century, had a huge hunting establishment including lions, cheetahs, caracals and falcons.

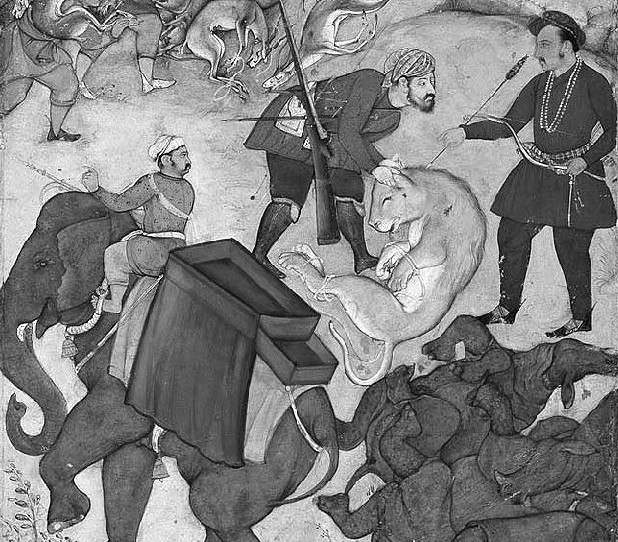

Mughal emperors, particularly, were known for their love of hunting, and this passion was often reflected in their art.

Mughal emperors like Akbar (reigned 1556–1605), Jahangir (reigned 1605–1627), and Shah Jahan (reigned 1628–1658) were frequently depicted hunting lions across the plains of India.

Under Mughal rule, the lion had become royal game in so far as only the emperor and his favored relatives, courtiers or guests would be permitted to hunt it. A successful lion hunt was a favorable omen, whereas if the lion escaped, it was

“portentous of infinite evil to the state”.

A successful hunt would result in the dead lion being brought before the emperor who would sit formally in durbar with his nobles. The carcass would then be accurately measured and it would be minutely examined.

Akbar kept detailed records of his shikar (hunting expeditions), including the weapons he used.

Similarly, Jahangir maintained meticulous records over his 39-year reign, documenting the hunting of 28,532 game animals and birds, including 86 lions.

In 1623, he slained a massive lion near Agra that weighed 255 kg and measured 9 feet 4 inches long, making it the 21st largest lion recorded in India and the heaviest ever recorded in the country, as male lions typically weigh between 145 and 225 kg.

The tradition of lion hunting by the Rajput rulers spans several centuries, particularly during the medieval period of India, from the 10th century to the 19th century. As a symbol of royalty and bravery, it was captured in various forms of art, especially Rajput miniature paintings.

The lion as a symbol of power and kings was also depict on the dhal or shields of kings and warriors. The dhal made of animal hide were light, handy, strong and durable and were preferred to metal shields. Such large shields are also known as dowry shields.

It was customary to carry the bride’s dowry consisting of jewels, money, arms…, on the concave side of the shield. An embroidered cloth would be placed on the shield under the gifts, or often the concave side of the shield was itself beautifully decorated.

The surface of this large rhinoceros hide shield is lacquered in black and painted over, gold leaf and silver are used aswell. It depicts lions attacking dear. The space in between is filled with plants and flowers to indicate a forest. Four lions run around the sun in the center.

Before the arrival of firearms, hunting in India relied on traditional weapons such as bows and arrows, spears, and swords. These weapons demanded great skill, accuracy, and bravery from hunters.

Paintings from this era often depicted not just the action of the hunt, but also its ceremonial and ritualistic aspects, showcasing elaborate processions with servants, elephants, horses, and hunting dogs.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the British East India Company and the British Raj introduced modern firearms to India, including rifles, muskets, and shotguns. Far more effective at hunting large game like tigers, elephants, and lions, due to their superior power, range, and precision, this animals were almost hunt to extinction.

Surname Singh

The common Indian surname Singh, meaning “lion”, has deliberate connotations of strength, power and prestige, dating back over 2000 years to ancient India. It derives from the Sanskrit word sinha, which means lion.

It was originally only used by Rajputs, a Hindu kshatriya or military caste in India since the seventh century.

After the birth of the Khalsa brotherhood in 1699, the Sikhs adopted the name “Singh” at the direction of Guru Gobind Singh.

As this name was associated with higher classes and royalty, this was to combat the prevalent caste system and discrimination by last name.

Along with millions of Hindu Rajputs today, it is also used by up to 10 million Sikhs worldwide.

Singh: The Lion beyond India

Iran

Public domain,edited.

The symbol of the lion is closely tied to the Persian people. Achaemenid kings were known to carry the symbol of the lion on their thrones and garments.

The Shir-va-Khorshid, or Lion and Sun, is one of the most prominent symbols of Iran. It dates back to the Safavid dynasty, and was used on the flag of Iran until 1979.

Sri Lanka

In Sri Lanka, the names “singha” or “singham” are used as an ending of many surnames.

“Weerasingha” meaning “courageous lion” is used by the Sinhalese people and “Veerasingham”, meaning the same, used by the Tamil people also.

Singhāsana (seat of a lion) is the traditional Sanskrit name for the throne of a Hindu kingdom in India and Sinhalese kingdom in Sri Lanka since antiquity.

Lord Buddha is depict seated on a lion throne in sculpturesres across Asia.

The entrance to Sigiriya, the Lion-Rock of Sri Lanka UNESCO heritage site, was through the Lion Gate, the mouth of a stone lion.

Lion Gate- Löwentor. Schmettau. CC -BY-SA 3.0, edited.

Singapore

The nation of Singapore (Singapura) derives its name from the Malay words singa (lion) and pura (city), which in turn is from the Sanskrit सिंह siṃha and पुर pura.

Recent studies of Singapore indicate lions have never lived there, and the animal seen by Sang Nila Utama was likely a tiger.

The Merlion (Chinese: 鱼尾狮, yúwěishī; Malay: Harimau-Laut; Tamil: கட்டல்சிங்கம்) is a statue with the head of a lion and the body of a fish, the symbol of Singapore.

The Asiatic lion makes repeated appearances in the Bible, most notably as having fought Samson in the Book of Judges, where he is slaying a Lion with his bare hands (Judges 14:5-6).

China

The Asiatic lion is the basis of the lion dances that form part of the traditional Chinese New Year celebrations.

The lion symbolizes strength, bravery, and the ability to bring good fortune. The lion dance is thought to scare away evil spirits, and the lion’s movements are believed to bring in positive energy for the new year (also known as the Spring Festival).

The Lion Dance can also be performed during other festivals like the Mid-Autumn Festival or Weddings. The dance is often performed in public spaces, such as streets, temples, or businesses, where the lion will “eat” offerings placed by the hosts and then give a blessing for prosperity.

Chinese guardian lions: The lion is not indigenous to mainland China, but Asiatic lions were found in neighboring India, as well as western Tibet.

With increased trade during the Han dynasty and cultural exchanges through the Silk Road, lions were introduced into China in the form of pelts and live tribute, along with stories about them from Buddhist priests and travelers of the time.

Shishi (石獅; shíshī) are guardian statues. Depictions of these “Fo-lions” have been found in Chinese religious art as early as 208 BC.

The Lions were thought to protect the building from harmful people and spiritual influences. Used in imperial Chinese palaces and tombs, the culture of guardian lions spread to many parts of Asia.

Bharat and the lion

The representation of lions in Indian art and architecture has been consistent throughout history, symbolizing continuity and preserving ancient cultural symbols.

Independent India is often depicted as Bharatmata (mother India), riding a full maned lion. India got its name ‘Bharat’ from Bharata a legendary emperor of India, son of King Dushyanta of Hastinapur and Queen Shakuntala. As a child he used to play with lion cubs and count theier teeth.

“[…]He (Dushyanta) grew to be strong and brave, and when but six years old he sported with young lions, for he was suckled by a lioness; he rode on the backs of lions and tigers and wild boars in the midst of the forest. He was called Alltamer, because that he tamed everything. […] (Indian Myth and Legend by Donald A. MacKenzie)

Bharata had conquered all of Greater India (including present day India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Nepal and Bangladesh) and united it into to a single political entity and the whole region was than named after him as Bharatvarsha (where varsha means part of earth).

A reference to it is in Vishnu Purana (2,1,32):

ततश्च भारतं वर्षमेतल्लोकेषुगीयते

भरताय यत: पित्रा दत्तं प्रतिष्ठिता वनम (विष्णु पुराण, २,१,३२)

This country is known as Bharatavarsha since the times the father entrusted the kingdom to his son Bharata and he went to the forest for ascetic practices.

From Buddhist symbol and the ancient Mauryan period to mughal medieval and even modern times, lions continue to be an integral part of Indian cultural heritage, representing a sense of continuity and pride in India’s traditions.

Here we can only give a small glimpse to the lions’ cultural heritage in India, there is still much more to discover.

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- Burgess, Jas. Indian Antiquary: A Journal of Oriental Research, Vol.5, Popular Pakistan, P.40. 1971.

- De Gubernatis Angelo. Zoological Mythology, or, The Legends of Animals, Vol. 1-2. 1872.

- https://macmillan.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/locked/Divyabhanusinh.pdf

- Karabi Kanungo. Thesis. Museum and communication: a case study of lion in Indian art (up to 6th century C.E.). 2018.

- PUSHKAR SOHONI. Old fights, new meanings. Lions and elephants in combat.

- https://journals.lww.com/coas/fulltext/2006/04040/junagadh_state_and_its_lions__conservation_in.2.aspx

- https://www.wisdomlib.org/hinduism/book/satapatha-brahmana-english/d/doc63479.html

- https://sacred-texts.com/hin/sbr/sbe44/sbe44067.htm

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2351989424005882

- Burgess, Jas. Indian Antiquary: A Journal of Oriental Research, Vol.5, Popular Pakistan, P.40. 1971.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pratyangira

- https://www.wisdomlib.org/definition/narasimhi

- https://groups.google.com/g/vallamai/c/beZxxhIEHyM

- Sacred animals of India. https://magazines.odisha.gov.in/orissareview/oct2004/englishPdf/lionmount.pdf

- https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in:8443/jspui/bitstream/10603/285530/1/karabi%20kanungo_thesis.pdf

- Balaji Gopalakrishnan et al. Lion and Half man Half animal deities in the Indus valley Civilization. Journal of Indian History and Culture.https://journalcpriir.files.wordpress.com/2020/03/2011-journal-17th-issue-for-web.pdf

- Karabi Kanungo.A case study of lion in indian art up to 6th century. 2018.

- Williams George M. Handbook of Hindu Mythology. 2003.

- https://www.bradshawfoundation.com/india/central_india/index.php

- Jampa Chisky Ven. Symbolism of Animals in Buddhism. Buddhist Himalaya. 1988.

- Burton Adrian. Lion of India. Ecological Society of America. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2011.

- Badam, G.L. , An Integrated Approach to the Quaternary Fauna of South and South East Asia- A Summary, Journal of the Palaeontological Society of India, Vol.58(1), P.93-114. 2013.

- https://jainqq.org/booktext/Jain_Heritage_and_Beyond_Romanized/006519

- Kausik Banerjee, Yadvendradev V. Jhala , Kartikeya S. Chauhan, Chittranjan V. Dave. Living with Lions: The Economics of Coexistence in the Gir Forests, India. 2013.

- https://zslpublications.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1469-7998.2010.00780.x