Discover mythology, history and traditional medicinal use of Omani Frankincense Hojari, once and today. Oman is permeated with frankincense, so prevalent that we immediately register the national signature scent. The fragrant gum resin is obtained from balsam trees (Boswellia), most commonly the tree resin is put on a heat source so that smoke is given off.

In this Article

The special container, an incense brazier is known in Oman as a Magmer, there the frankincense smoulders and gives off its fragrant smoke. In about 30 minutes, the small nugget is completely burnt, but the fume lingers, the fruity fragrance persists in the air, fresh with pine and a citrus background.

Omani frankincense or hojari is considered to be the finest in the world. It is used on social occasions, used in the manufacture of medicines, fragrants, powders, perfumes, candles as well as in halls of worship around the world.

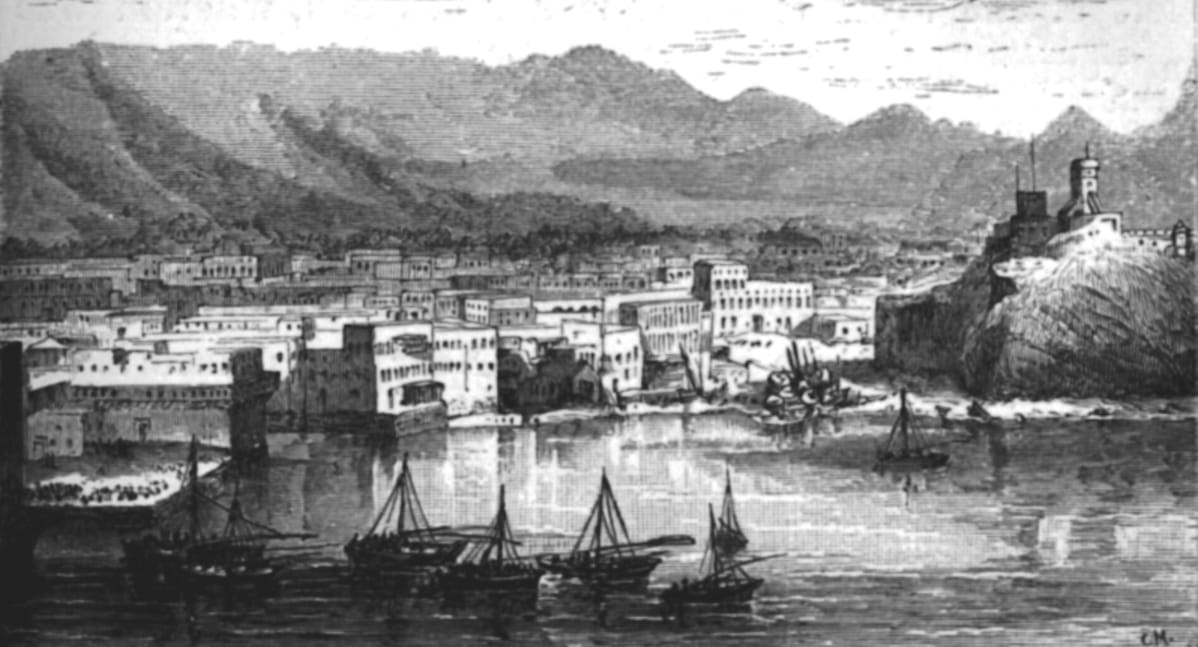

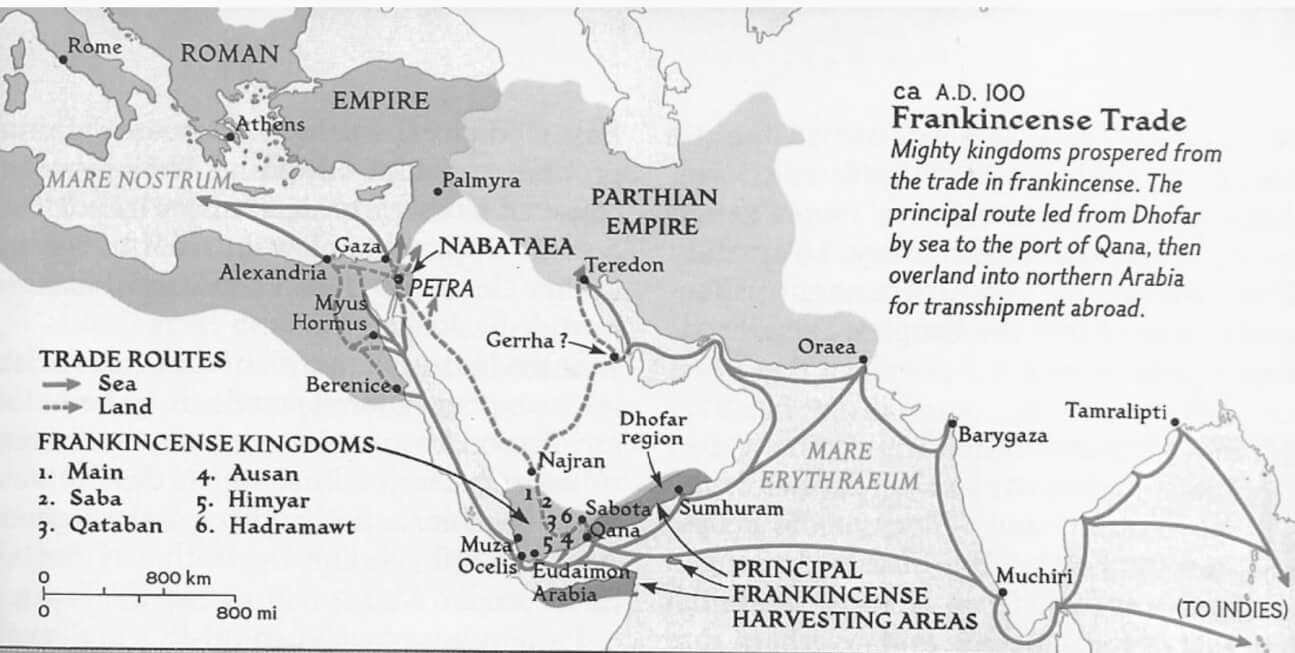

The incense trade played a key role in the early history of the Arabian Peninsula — bringing immense wealth to omani ports and cities and also permitting cultural exchange between diverse civilizations.

At one point in history hojari was so coveted, that the southern Dhofari ports were considered the nexus of the global frankincense trade, from where it was shipped to Mesopotamia, Pharaonic Egypt, Ancient Greece and Rome, as well as to the kingdoms of India and China.

The Omani say of Frankincense:

“From my branches flows the fluid to which millions of hearts beat on hearing its name”

Oman – Land of Frankincense

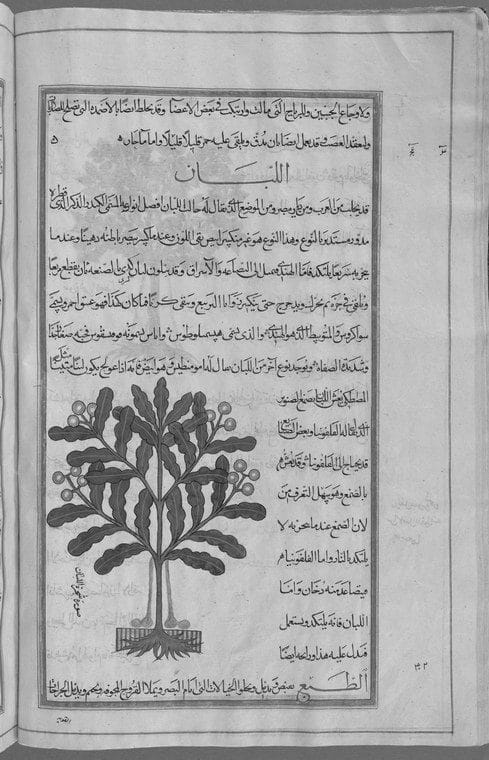

Arab writers referred to the area as al-Shihr and eulogized its principal product, in Arabic called luban. One poet said,

Go to al-Shihr and leave Oman;

You’ll not find dates but you’ll find luban.

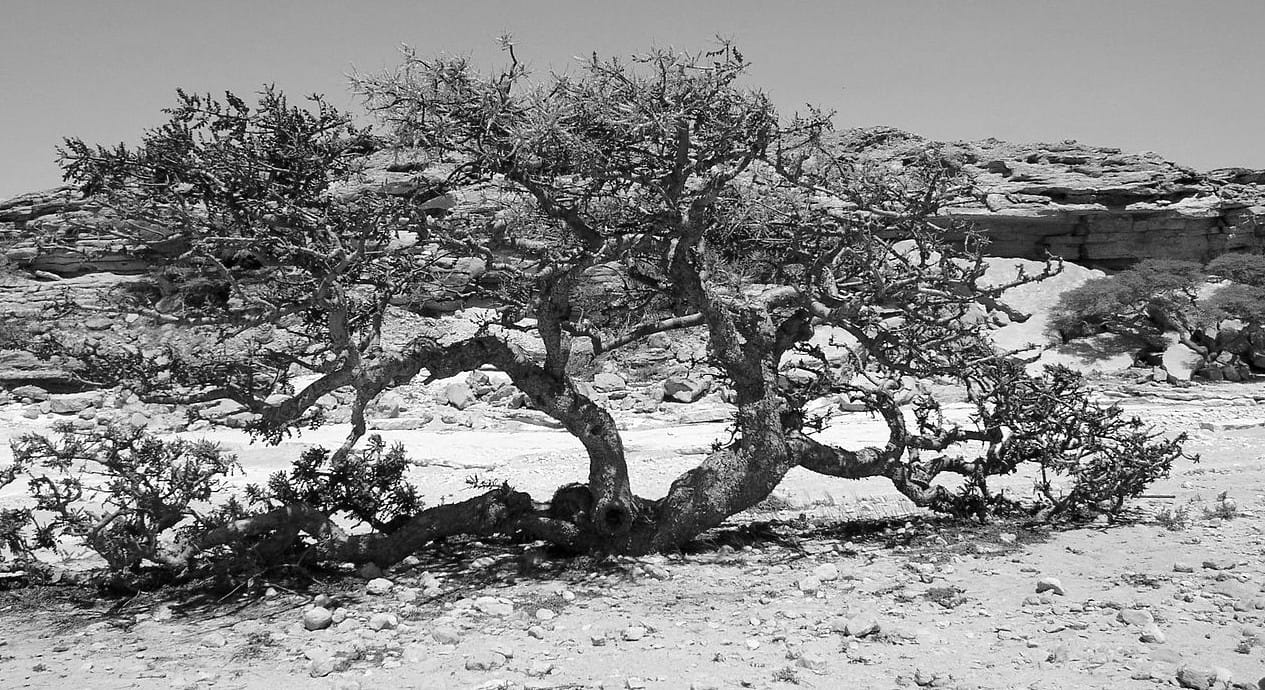

The implication, perhaps, is that if dates are of life, frankincense is the equivalent for the soul. We had traveled nearly 2000 kilometers (1250 mi) from Muscat to learn about omani culture, nature and heritage. Nevertheless Salalah (once called al-Shihr), the capital of the Sultanate of Oman’s Dhofar Governorate was not on our route. We did not follow the poet’s advice and missed the hardy, scraggy Boswellia trees. Yet the omnipresent odor of Oman — frankincense — draw us into its spell.

“Arabia has been famously fragrant since the earliest times. Kitab al-Tijan, probably the oldest Arab history book, has Ya’rub, the first speaker of Arabic, following the scent of musk southward from Babel.

Greek and Latin authors wrote of an Arabia redolent with spices and aromatics. In Shakespeare’s 17th-century view of 11th-century Scotland, Lady Macbeth wailed that all the perfumes of Arabia would not sweeten her blood-stained hand.

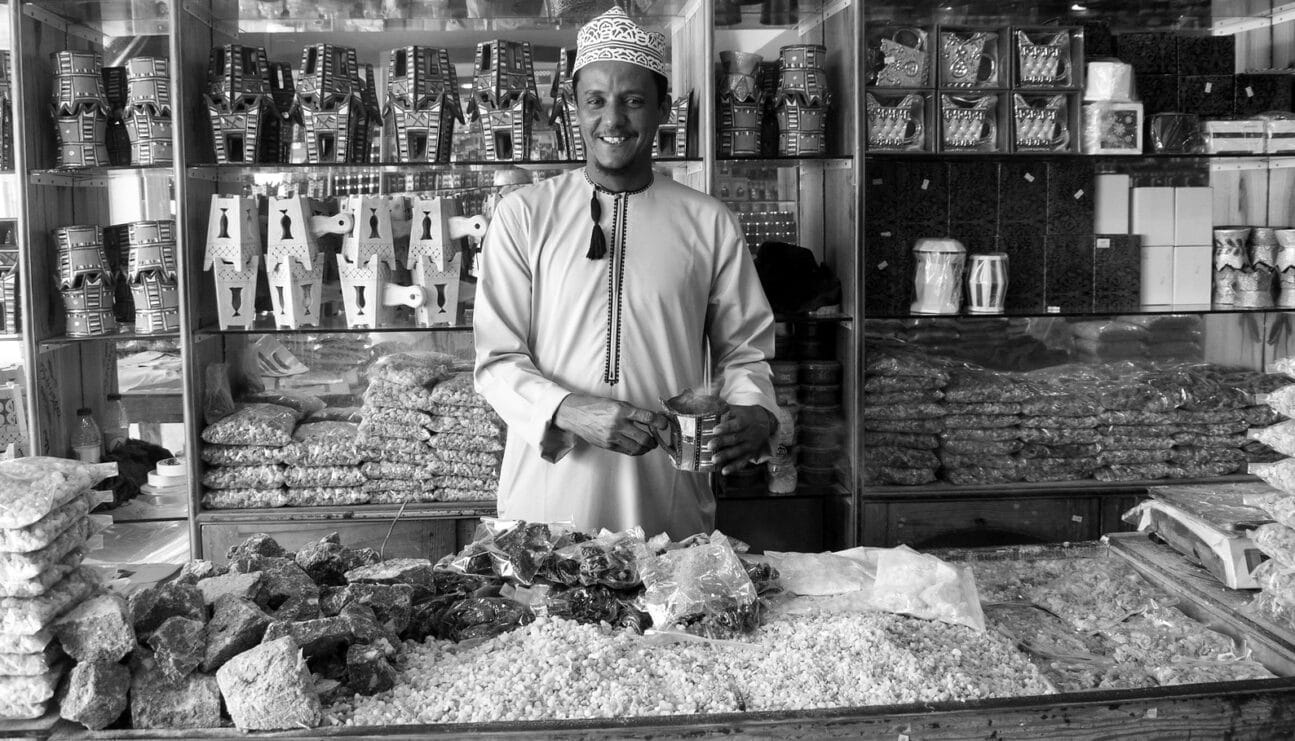

Smelling Mutrah Souq سوق مطرح

A deep breath in the Mutrah Souq at Muskat proves that all this is no mere literary cliche: There are bottles and flasks of scent by the thousand, ranks of pottery incense brazier, and jar upon jar of obscure ingredients, waiting to be pounded, compounded and combusted by the ladies of Oman. Amid mysterious aromas (animal, vegetable, mineral?), I detect a few familiar notes: lime, musk, honey, ginger, cinnamon, rose, jasmine, pepper, and sandalwood. Few of the raw materials are local; most come from around — and in — the Indian Ocean, still as generous a sea as it was for the Arab navigators of the Middle Ages.

One of the most prized fragrance items is Oudh — the Wood of the Gods —the tar-like resinous heartwood that forms in the ancient Aquilaria and some Gyrinops species of trees that are native to the dense forests of South East Asia.

One product, though, is entirely indigenous to the southern Arabian Peninsula, and among all the sweet and heavy odors it provides an unmistakably clear note: frankincense.

The scent of its smoke is everywhere, rich but not cloying, honeyed yet slightly astringent, with hints of lime, vetiver and verbena — the olfactory equivalent of a good limoncello. For thousands of years, this inimitable odour has carried the fame of Arabia felix (Blissful Arabia) across three continents. The historian AI Tabari wrote

” The smoke of incense reaches heaven as does no other smoke”.

Interestingly, our modern term perfume comes from the Latin “per fumum”, through smoke. Writing in 1355, the great Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta reported that the suq, [market], of the southern Arabian city of Zafar smelled so vile, “because of the quantity of fruit and fish sold in it.”

The smells of this suq would please Ibn Battuta, just as they please modern-day visitors: The occasional ghostly whiffs of drying sardines are overwhelmed by a voluptuous aura of aromatics coming from the simple stalls and voluptuous perfumery houses. As one Omani said to me, splashing attar, a fragrant essential oil, on the tassel of his dishdashah (a long usually white robe traditionally worn by men in the Middle East), and on me,

“Scent? We can’t live without it!”

Per capita, men and women in the Persian Gulf are the biggest spenders on luxury perfume in the world. To visit a souq is to enter Oman’s rich, diverse and ancient heritage and to have their senses stimulated by the aromatic smells of frankincense, various kinds of resins and Arabic perfumes.

We see freshly harvested myrrh (a brown, crumbly resin with a cinnamon-like kick), ambergris (lumps of partly digested giant squid beaks, excreted by sperm whales, that wash up on Oman’s coastline), and dhufr (fishy-smelling sea snail shell flaps, which look like blackened toenails and are powdered for use as a perfume fixative). This unexpected ingredients are naturally used in high quality perfumes.

In search of Hojari

The trade, at least in the perfume department, is run by women. Their stock spills out of their shops and on to the pavement, where they sit among piles of frankincense and other aromatics.

Watching the tide of Omanis inspecting mountains of frankincense nuggets, sorting and pricing according to color and source, we try to understand how to determine quality and price ratio. I ask two ladies, clad in full-length black abayas, head scarfs, and face veils:

“Where can I find good quality frankincense?”, they look at each other and answer unison

“Not here!”

One of the ladies would glide into her abaya, take out a shiny cardholder, open it and handling me over a visit card, with golden letters, say: “That’s the place! Here you find what you need.”

After some asking and showing the card around we end up in a brightly lit high scale perfume house in Muskat`s old quarters:

“Of the hojari resins from Oman, Green Hojari is the most sought after of all.”

Fathima, says, sprinkling small drops of hojari onto a hot disk of charcoal in a red-and-gold-painted incense brazier.

Between samples, women sniff an open tin of ground coffee to clear their olfactory receptors (I’m immediately reminded of a wine-tasting session), then use their right hands to scoop smoke tendrils up to their nostrils.

After the ladies left, heavy – with several bags, Fathima arranging her head scarf indicates with her kohl-rimmed, smoke-shot eyes that we should come near.

We listened as Fathima went through the different grades of frankincense in stock. “Those big yellow lumps aren’t so good,” she said.

“These are better. Look, they’re like pearls. But,” she opened a box with her henna painted hands, “these are the real fusus” Her word “gems” was well chosen: Teardrops, some were silvery, others had opalescent hints of rose, green or blue. “This is najdi,” she explained, “from the najd [plateau], the high land behind Jabal Qara.”

I had already made inquiries about where the best frankincense comes from and how to recognize good quality from bad one. My informants, however, could not agree. In another shop, one had said that the best one is glassy white. A hotel clerk said that the best came from the border with Yemen and is pearl white.

A souq seller assured, the bigger the lumps the higher the price. “I like to say the white has more a green, herbal, butterfly note while the black has an orange floral spice aspect.”, a poet shop clerk added. Can we trust the savvy merchants of the souq?

The literary sources were similarly in disagreement. “The finest luban of all you won’t find in a suq,” added Fathima, confusig the matter further. “It’s called hojari and it comes from the Al Hajar Mountains. We sell it, have a look. Take a tea first…”

Hojari هوجاري

The Chinese recorded 13 different qualities in their trade during medieval times. However, there are four principal differentiations in quality that are commercially observed:

- Thiki (used for medicinal purposes),

- Hojari (the best – up to the size of a Brazil nut and of a creamy slightly transparent, colour. Of the frankincense resins from Oman, Green hojari is the most sought after of all. It is green when fresh but turns yellowish with age.),

- Nejdi (medium grade) and

- Shahazi (lower grade).

Hojari هوجاري (also spelled hajari, hawjari, hougary, hogary) is – Superior grade frankincense, named after the Al Hajar Mountains. Each type of resin is available in various grades, these depend on the time of harvesting and is hand-sorted for quality.

From tea connoisseurs I know, about the importance of the right harvest time, to frankincense it is the same, I learn on the website of the Salut museum, Oman:

Four different qualities of frankincense are produced: t

he intensely fragrant Al-Hojari harvested in the zone furthest inland during the hottest period of the year;

Annajdi, which is produced during the months following the monsoon;

Ashazri, which is gathered at the beginning of the rainy season; and the least prized variety,

Asha’bi, harvested during the coldest months of the year from trees growing along the coast.

Considered by many to be the finest frankincense in the world, Hojari is primarily the larger selected white and lemon-white colored frankincense resins. The highest quality has various tints of green as well. Superior hojari frankincense resins produce beautiful light, bright, citrus or orange aromas with slight underlying woody and balsamic tones.

As we were packing our “lifelong” supply of frankincense and Oudh wood, I was grateful to the two ladies, that had brought us to this shop, were we had learned so much about frankincense, sipping sweet tea and scents. And suddenly the two were here, one lady would hand me over a small packet with the words:

“From an Omani woman for you.”

This act of kindness touched me deeply, and still gives me chills remembering it. Shukran jazeelan — Thank you very much, Omani ladies for your advice, generosity and warmth.

MYTHOLOGY OF THE FRANKINCENSE TREE

Tree lore: On how the frankincense tree come to be

This old story is from Dhofar in Oman.

Agirl from jinn [beings that are concealed from the senses] fell in love with a human boy. Since this love was a violation of the jinn rules, they decided to punish her and transform her into something else. She cried for a long time and after they insisted that she must be punished, she chose to become a tree.

Thousands of years passed by and this silent and hurt tree that’s called frankincense continued to shed tears in the form of resin that solidified into white particles which smell of musk. It is therefore a girl in the shape of a tree weeping over her beloved.

Crystal tears that taste of grief came out of the trunk and people scattered them on burning coal to turn it into pure smoke with a scent that heals the sick and with a bitter taste that grieves for lost love. A beautiful tree, which suffered as a result of love, heroically produced a material that healed people. Isn’t it love that we seek from each other?

Beasts of frankincense trees

The earliest records of the collection of frankincense and the trade in the gum are shrouded in an often impenetrable mantle of myth and magic; for example, the precious gum-bearing trees were said to be guarded by fierce red snakes which leap into the air to inflict their fatal bites on any intruder; or the trees were believed to grow in an area of swirling mists, the course of deadly disease and fatal epidemics, a place both mountainous and forbidding, wrapped in a dense cloud and fog.

Vicious flying serpents

In the history of Diodorus of Sicily, we find a description of dark red poisonous serpents amongst the frankincense trees.

~ Library of History Book III.46-47.

Herodotus of Halicarnassus (c.480-c.429 B.C.), the great traveler known as the “father of history, also describes these creatures:

The frankincense they procure by means of the gum styrax, which the Greeks obtain from the Phoenicians; this they burn, and thereby obtain the spice. For the trees which bear the frankincense are guarded by winged serpents, small in size, and of varied colors, whereof vast numbers hang about every tree. They are of the same kind as the serpents that invade Egypt; and there is nothing but the smoke of the styrax which will drive them from the trees.”

~ Herodotus Histories Book III.107, trans. George Rawlinson, 1858-1860; found here in the 1997 Everyman’s Library/Knopf edition on p. 276.

Herodotus is often criticized for an over-fertile imagination, but the Dhofari scholar Sa’id al-Ma’shani has noted the existence of a rock drawing from the region which shows a man’s leg and a snake. Possibly, he suggests, this is an ancient “No Trespassing” sign.

Herodotus description of the flying serpents is based on fact. North East African Carpet Vipers, Echis pyramindum pyramidum or Echis khosatzkii infest the mountains of Dhofar into the present time.

These snakes coil up and strike high, almost as though they were flying. They are also said to leap onto victims from samur trees. The bite is quite toxic and there is no known antidote.

Magical Phoenix

Frankincense has been long associated with the phoenix, a mythical and mysterious bird. This legendary bird was said to originate from Southern Arabia, and to feed there on the tears of the frankincense tree, on the dew from heaven and on frankincense blossoms.

Every five hundred years it flew to Heliopolis to bury its dead father, who was wrapped in a shroud saturated in myrrh. A Hebraic term ‘hol’ was used to describe the Phoenix: in ancient Hadramawt there was a god called ‘hwl’ and it is claimed by some scholars that the Phoenix legend was brought north by south Arabian traders, and was the source of the belief that frankincense was a gift from the gods and southern Arabia the origin of all precious scented woods and spices.

Pliny the Elder in the 1st century C.E. writes after Ovid:

The phoenix, of which there is only one in the world, is the size of an eagle. It is gold around the neck, its body is purple, and its tail is blue with some rose-colored feathers. It has a feathered crest on its head. No one has ever seen the Phoenix feeding. In Arabia it is sacred to the sun god. It lives 540 years; when it is old it builds a nest from wild cinnamon and frankincense, fills the nest with scents, and lies down on it until it dies. From the bones and marrow of the dead phoenix there grows a sort of maggot, which grows into a bird the size of a chicken. This bird performs funeral rites for its predecessor, then carries the whole nest to the City of the Sun near Panchaia and places it on an alter there.

~ Natural History, Book 10, 2

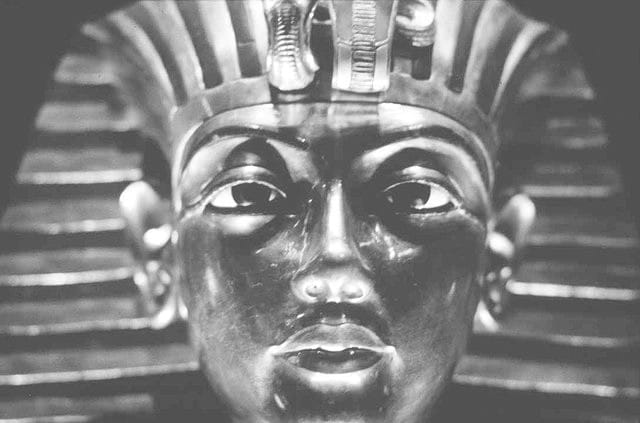

Frankincense and the Egyptian Gods

Tutankhamen – Living Image of Amun

When Howard Carter opened the tomb of the Egyptian Pharaoh Tutankhamun in 1922, incense was found. The chemist who examined the resin, A. Lucas, believed it to possibly be powdered frankincense rolled into balls. When smouldered, Lucas found it still fragrant after 3,500 years, giving off a ‘pleasant aromatic odour.’

As these “tears” solidify into an alluring mass of silver, golden, and amber colors that, in and of itself, are a sight to behold. Egyptians, according to “Plants of Dhofar,” believed this to be

“the sweat of the gods, fallen to earth.”

In the Book of the Dead, the ancient Egyptians the authors recommended the use of incense in many of the mortuary rituals and in ceremonial purification. Kindled in clay troughs and the flame doused with cows milk, frankincense was recommended for warding off evil and enemies malevolence.

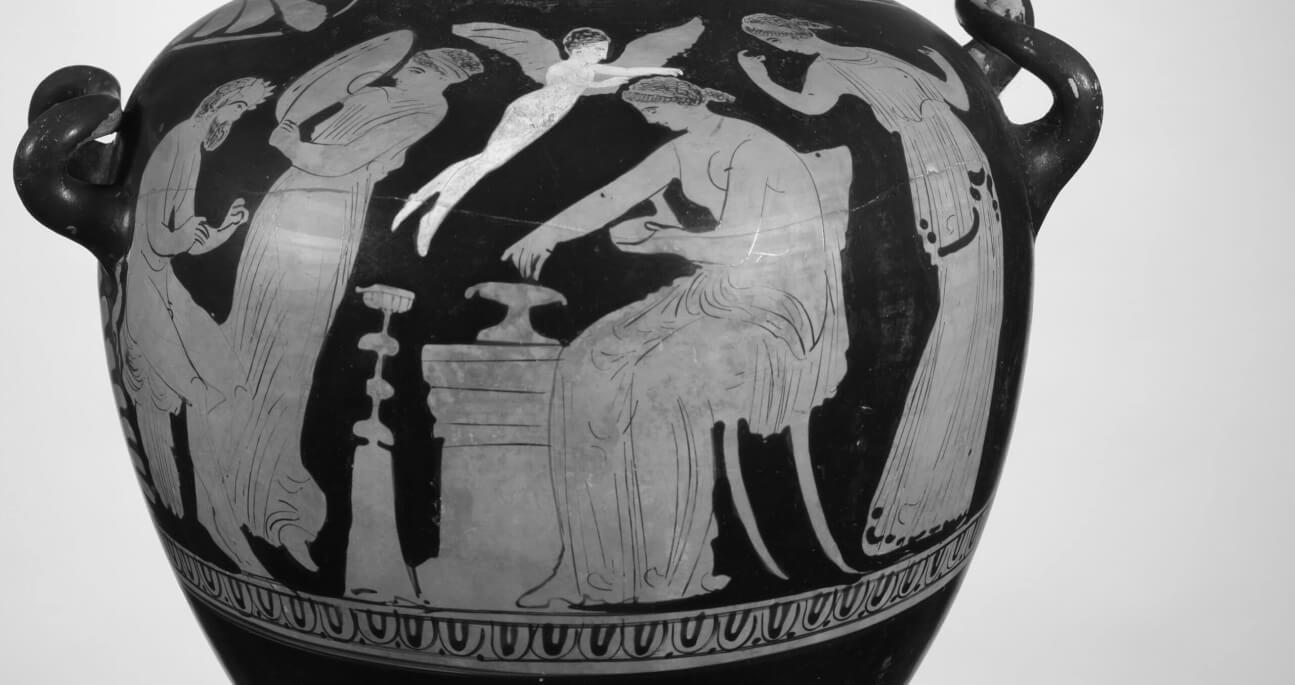

Frankincense, the Greek and Roman Gods

Pythagoras, philosopher-mathematician and priest of Apollo, performed libations and sacrifices to Gods with “fumigations and frankincense” instead of sacrificing animals.

“He used to practice divination, as far as auguries and auspices go, but not by means of burnt offerings, except only the burning of frankincense.”

In the writings of Herodotus (330 B.C.), ” the Chaldeans of Babylon offered a thousand talents’ weight (98,422 pounds) of frankincense to (Zeus)-Bel at his yearly festival. By 1 B.C., 3000 tons of frankincense were exported to Greece and Rome from Southern Arabia.

Tree lore: Ovids Metamorphoses – Leucothoe, Princess of Persia

There is connection in antiquity between frankincense and the sun. Ovid sung of the creation of the frankincense tree and the heliotrope (a plant whose flower follows the sun) involving Sol and the love set in his heart by Venus/Aphrodite for Leucothoe.

Leucothoe or Leucothoe was princess of Persia (Achaemenids), and daughter of Orchamus and Eurynome, the king and queen of Persia. Helios, the sun god, was attracted towards Leucothoe’s beauty. Helios, who was able to see all deeds from both morals and immorals, only gazed Leucothoe. One night, Helios gained entrance to Leucothoe’s chamber, where Leucothoe was with her twelve maids. Helios transformed himself into Leucothoe’s mother, Eurynome, and appeared before them.

In form of Leucothoe’s mother, Helios asks maids to leave the chamber as she waited to speak with her daughter in privacy. When room was was left without a witness. Helios took her in his arms and kissed her. Fear gripped Leucothoe heart, she known something is wrong. Helios resume his own true shape and seduce her.

Clytie, an oceanic nymph loved by Helios, abandoned her for Leucothoe, was jealous and in anger spread the tale of Leucothoe shame. Clytie make sure that Leucothoe’s father, Orchamus, knew the tale of Leucothoe shame.

Orchamus came to know about it, even Leucothoe told that Helios ravished her against her will, in anger he ordered to buried her alive deep in the earth.

Helios tried to save her, but he was late, she was crushed by the weight of earth. Helios changed Leucothoe lifeless body into a incense plant (tree of frankincense).

According to some versions, Thersanon was son of Helios by Leucothoe. Apollo was also associated with sun, and was even identified with Helios, the sun god. So in some versions Apollo is described who seduce Leucothoe.

Leucothoë reborn as the frankincense tree

Goddess Venus (Aphrodite) was furious with Sol (Helios the Sun) for exposing her love affair with Mars (Ares) to her husband Vulcan (Hephaestus).

To avenge herself, she made Sol fall in love with Leucothoë. Sol disguised himself as Eurynome, Leucothoë’s mother, to gain entrance to Leucothoë’s chamber. He then united with her. But her sister, Klytie, had fallen deeply in love with Sol. The jealous girl revealed the affair to her father, who then buried Leucothoë alive.

By the time Sol discovered the punishment of her father, Leucothoë had died. Unable to awaken his beloved with light, Sol swore to revive the girl and make her rise to the sky. He covered her in the nectar of the Gods.

The body of Leucothoë melted away and filled the soil with its fragrance, and out of the earth arose the frankincense tree, for this land of Persia burns with the sun, and therefore frankincense is associated with the Sun.

When Sol refused to forgive Klytie, she died of sorrow and the God changed her into the heliotrope, a flower which follows the sun. For the ancient Greeks, the word ‘scent’ itself meant

“offering to the gods”

~ Libanos

Frankincense in Christianity

For the time being, the religious custom of smouldering incense dwindled with the rise of Christianity and the suppression of the older traditions, to which its use was greatly associated.

“The creator and father of the universe does not require blood,

nor smoke,

nor even the sweet smell of flowers and incense”

Athenagoras the Christian apologist (133 CE-190 CE)

Eventually the use of incense were punishable by law:

(Cod. Theod. xvi. ro. 4, 6), forbidding all sacrifices on pain of death, and still more by the statutes of Theodosius (Cod . Theod. xvi. 10.12) enacted in 392, in which sacrifice and divination were declared treasonable and punish-able with death; the use of lights, incense, garlands and libations was to involve the forfeiture of house and land where they were used; and all who entered heathen temples were to be fined.

Frankincense in the Bible

Frankincense was a key part of the sacrifices to Yahweh in Old Testament worship. In Exodus, the Lord said to Moses:

Gather fragrant spices—resin droplets, mollusk shell, and galbanum—and mix these fragrant spices with pure frankincense, weighed out in equal amounts. Using the usual techniques of the incense maker, blend the spices together and sprinkle them with salt to produce a pure and holy incense. Grind some of the mixture into a very fine powder and put it in front of the Ark of the Covenant, where I will meet with you in the Tabernacle. You must treat this incense as most holy. Never use this formula to make this incense for yourselves. It is reserved for the Lord, and you must treat it as holy. Anyone who makes incense like this for personal use will be cut off from the community.”

~ Exodus 30:34–38, NLT

Epiphany

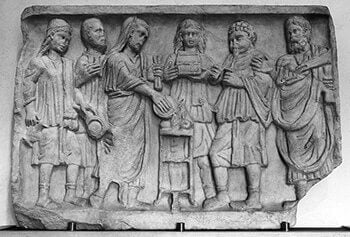

Wise men, or magi, visited Jesus Christ in Bethlehem. The event is recorded in the Gospel of Matthew, which also tells of their gifts:

“And when they were come into the house, they saw the young child with Mary his mother, and fell down, and worshiped him: and when they had opened their treasures, they presented unto him gifts; gold, and frankincense, and myrrh.”

Matthew 2:11, KJV.

The Christmas story of three wise men or magi, goes as followed:

A star appeared, and the wise men of the East—perhaps they were Persians or Arabs—were certain that it signaled the birth of the King of the Jews, so they went to Jerusalem to inquire where He had been born. After their audience with the scheming Herod, they made the five-mile journey to Bethlehem and, finding the Child, adored Him and offered Him the gifts most valued in the East: gold, frankincense and myrrh. Gold is offered in tribute to a king; incense, in sacrifice to a deity; and myrrh, a fragrant resin, is used to embalm or sprinkle on dead bodies—an odd present for a newborn baby, to be sure, but a clue to why He came into our world.

Travels in Arabia, Bayard Taylor. 1898 Edit. Thomas Stevens for Project Gutenberg. 2013. Public domain, edited.

Legend has it, the Magi followed a star and perhaps the prophecy of the Gentile prophet Balaam: “A star shall come forth out of Jacob and a scepter shall rise out of Israel” (Num 24:17).

Caspar, Melchior and Balthazar are the most accredited names of the wise man, according to the Western tradition. Melchior is the oldest, and his name comes from Meloch, “King”; Balthazar probably owes his name to the Babylon king Balthazar; Caspar, or Galgalath, means “Saba’s lord” in Greek. Another tradition says that Balthazar was the King of Arabs, Melchior King of Persia, and Caspar King of India. Nothing is sure though. Chinese Christians claim that one of them came from China.

Today, the day of the Magi’s arrival is known as Epiphany, Three Kings Day or, also known as Twelfth Night, and depending on the brand of Christianity, it is celebrated anywhere between January 6 for Catholics and January 19 for Orthodox Christians.

Frankincense was burned to accompany prayer:

‘‘the crowded congregation was praying at the actual time of the incense burning’’

Luke 1:10

‘‘golden bowls full of incense, which are the prayers of the saints’’

Revelations 5:8

‘‘and the smoke of the incense rose up before God mingled with the prayers of the saints’’

Revelations 8:3

It was also thought that the white smoke carried the prayers up to heaven (Armenian Orthodox). By the Middle Ages, frankincense was incorporated into regulated use, with detailed instructions on its use (Catholic Encyclopedia), till today.

Frankincense in the Sunnah

The growth of Islam curtailed the use of frankincense in the Middle East, since Islam does not require the burning of incense in religious rites and ceremonies. However, the aroma of frankincense is said to represent life, and the Judaic, Christian, and Islamic faiths have often used frankincense mixed with oils to anoint newborn infants and individuals moving into a new phase in their spiritual lives.

Ibn al-Qayyim, in his Zad al-Ma’ad, includes a short discussion of frankincense under a section on medicinal treatments. He mentions a report of the Prophet (peace be upon him) telling his companions to fumigate/burn frankincense and thyme to help to expel evil spirits (demons and certain jinns) from the house.

“Use frankincense, for it invigorates the heart with courage, and it is a remedy for forgetfulness,”

the ‘Ali (may Allah be pleased with him) himself recommended frankincense to a man who had complained to him about memory loss or forgetfulness. The same is reported of Ibn ‘Abbas and Anas.

Ibn al-Qayyim explains these reports through medieval theories of medicine. He also lists numerous other benefits of frankincense, such as helping with stomachaches, indigestion, sharpening vision, and so on.

In the 13th century, Ibn Arabi, an Hispano-Arab mystic, wrote in his “Pearls of Wisdom ” that

“of all the wordly goods, three things are dearest to my heart, perfume, women and prayer.”

HISTORY & HERITAGE: The Frankincense Route

The Frankincense Route was listed by UNESCO in 2000, it writes:

“The frankincense trees of Wadi Dawkah and the remains of the caravan oasis of Shisr/Wubar and the affiliated ports of Khor Rori and Al-Balid vividly illustrate the trade in frankincense that flourished in this region for many centuries, as one of the most important trading activities of the ancient and medieval world.”

Ancient Incense Trade Route

Supported by geology and archaeological evidence of trade in shells and obsidian shows that pastoral nomads in Dhofar, Oman had already established ancient trade routes to southern Mesopotamia in the Neolithic period. Early importation of frankincense is also supported.

This suggests an inland route existed across the Rub al Khali [gravel desert towards the Saudi Arabian border] and ultimately to Mesopotamia, possibly as early as 6000 B.C.. Historians squabble over the estimated antiquity of the commerce. Some believe it dates as far back as 3200 B.C, while others agree on a more recent 1500 B.C.

The earliest tangible record of incense use in Mesopotamia is an incense burner found in the ruins of a temple at Tepe Gawra, near Mosul in modern Iraq, dated around 3500B.C..

The Frankincense Route was full of complications for the early people, who struggled through relentless terrains in long donkey and then camel caravans of people. There was a lack of maps and navigation systems (although they were excellent at guiding by the stars), a constant presence of robbers and various kingdoms along the trail that tried to collect tolls at the slightest opportunity.

The dromedary was domesticated around 1000 B.C. and this development allowed the Arabs to begin transporting their valuable incense to the Mediterranean. Frankincense and myrrh became a significant commodity for the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans—

The Temple of Baal, in Babylon, for example, burned two and a half tons of frankincense a year, according to ancient records, and in Rome, Pliny says, emperor Nero burned an entire year’s production of incense from Arabia at the funeral of his wife Poppaea. The camel caravan could take six months, had fifty stops, and was a challenge to survive it at all times.

Crossing the Syrian Desert, they surrounded Palmyra (less spectacular after Islamic State militias occupied it in May 2015, dynamiting for the sake of intolerance the Temple of Bel and the Temple of Baal Shamin and destroying the unique funerary towers and the famous Arc de Triumph).

Then they passed through Jordan, Amman (named Philadelphia 2000 years ago), and Aqaba on the Red Sea. Aqaba was complementary to Petra’s trading activities — the nearby capital of the Nabataeans — and the trade routes of Wadi Rum.

Southern tribes held the ways to south Yemen, where Medina, once a bustling crossroads for the camel caravans that were Arabia’s lifeline, and today the second holiest city in Islam, was located.

In the third quarter of the sixth century, a Himyarite ruler named Abraha marched on Mecca. An elephant was part of his army and, as a result, the southern part of the Incense Route came to be known as the “Elephant Road”.

The northern part of the route was used by merchants like prophet Muhammad (peace upon him), who was born in the “year of the Elephant” and is mentioned as traveling all the way up north to Bosra near Damascus. According to Islamic legend, a Christian monk identified the merchant from Mecca as a messenger of God.

In the confused years after the death of the prophet (probably in 632),we see army movements along the ancient roads, which have been also used by Muslim pilgrims to Mecca, Islam’s holiest city as the birthplace of the Prophet Muhammad and where the sacred book for Muslims (Quran) was composed.

Incense Trade Route – Egypt

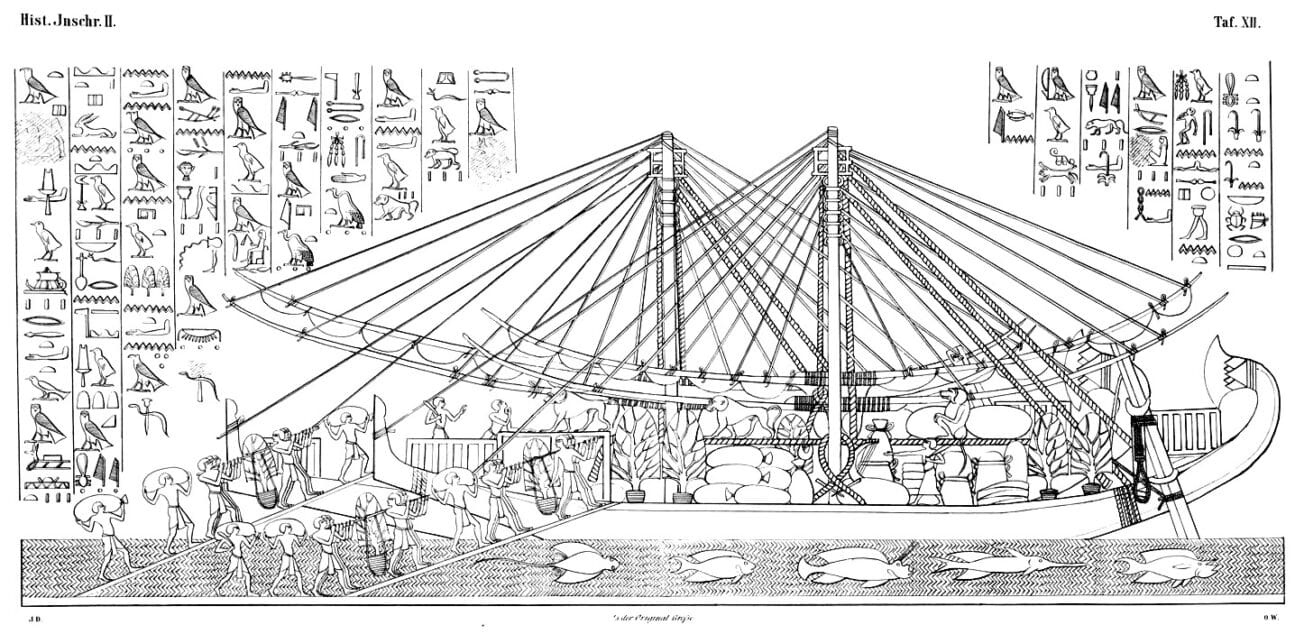

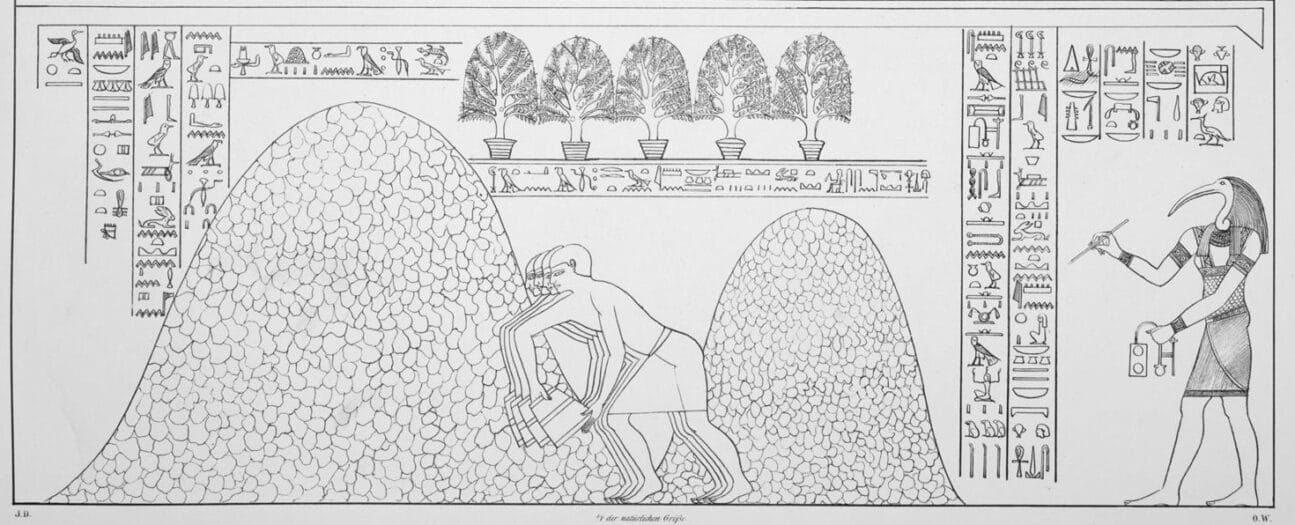

The earliest reference of frankincense trade comes carved in stone. In Pharaonic records of around 1500 B.C., which state that the resin came to Egypt from “the Land of Punt,” probably located in the Horn of Africa. Pharaoh Hatshepsut, herself informed us in lengthy inscriptions on the walls of her terraced temple at Deir el-Bahri, near Luxor in the Valley of the Kings, that

“… the ships were laden with the costly products of the Land of Punt and with its many valuable woods, with very much sweet-smelling resin and frankincense, with quantities of ebony and ivory …”

The trees never flourished to produce the homegrown frankincense the Egyptians had hoped for. Undeterred they continue to import massive quantities for everyday use and for special celebrations such as weddings and funerals.

Incense Trade Route – Persia

In Persepolis and Susa (modern day Iran), frankincense was a prized commodity. By the middle of the first millennium B.C., Darius I from Persia (521–485) had conquered the northern part of India. This reinforced the direct trade between India and Mesopotamia via the Persian Gulf and the Euphrates and Tigris rivers.

The Persians aimed at creating a naval link between the Persian Gulf and Egypt and the Mediterranean, via the Red Sea. King Darius I of Persia received an annual tribute of over 2.7 tonnes of frankincense from the Arabs. The use of spices for personal and ritual use was common among the Persians by the sixth century B.C.

Incense Trade Route – Mediterranean

But by the Greco-Roman period Boswellia sacra had captured the markets, Frankincense commanded fabulous prices- the value of frankincense and myrrh in the markets of the Roman Empire, for instance, was at times equated with gold.

The Omani researcher and historian, Abdul Qadir bin Salim Al Ghassani, mentions in his book ‘Dhofar, the Land of Frankincense’ that Alexander the Great had imported huge quantities of incense from Arab lands.

Ibn al Mujawir in his Ta’rikh al Mustabsir describes the bi-annual north-south route via Baghdad through the desert to “Zafar”, “Mirbat’, and “Raisut.” The trade flourished, and the overland route was, at its height, said to have seen 3000 tons of incense traded along its length every year. The distance mentioned by Pliny, who states that between Shabwa and Gaza, the merchants passed sixty-five stations and covered 2437.5 Roman miles or 3609 kilometers or 4436 miles.

Although at times, the route shifted when greedy settlements pushed their luck and demanded taxes that were too high from the caravans coming through. The Assyrians, then the Persians and the Greeks, were at various times in control of part of the Incense Road. The Arab trade for the most part was unaffected, and, under the various occupiers, the Arabs were able to carry out trade with India relatively unhindered. By the first century CE, this ancient overland route was largely redundant, as sea routes were used.

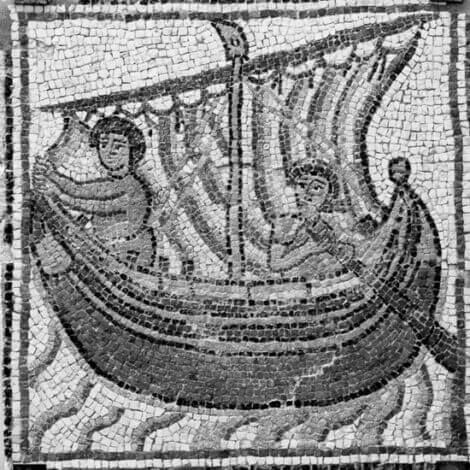

The Roman Sea Trade Route

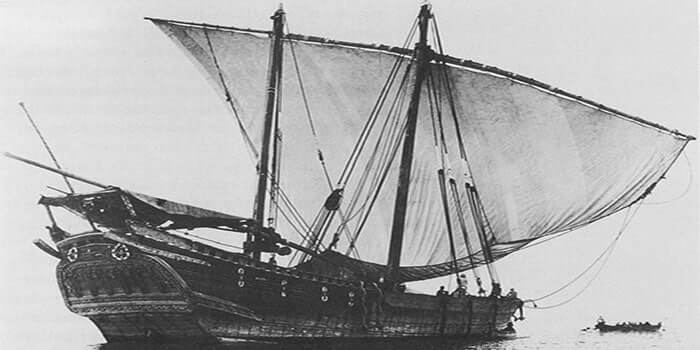

Traders from Persia, Arabia, India, and other coastal areas used triangle-sailed dhows to harness the seasonal monsoon winds.

Caravans helped bring coastal trade goods such as silk, porcelain, spices, incense, and ivory to inland empires, as well. Enslaved people were also traded.

Strabo remarked:

‘‘The part of Arabia that produces the spices is small and it is from this small territory that the country got the name Felix (Fortunate or Blessed Arabia) — because such merchandise is rare in our part of the world and costly’’

Later the frankincense trade collapsed, because the Christians – who increasingly dominated Roman society – considered incense-burning idolatrous.

The fall in demand resulted in the demise of the roman sea route.

The Frankincense Road remained lost, quite literally, to the sands of time. Because it passed through what is today the Great Arabian Desert, an immense expanse of land in Oman and Saudi Arabia that is so meteorological and geological punishing that no human settlement dared to drop permanent anchor there.

Well and truly bereft of modern civilization, it acquired a name as intriguing as its character: Rub’ al Khali—The Empty Quarter. But time was when it was not so arid or inhospitable.

In fact, the evidence is compelling that there was ample water here to support the frankincense caravans that made their way to Mesopotamia, Mekka and Jerusalem.

Centuries ago, after the Roman Empire declined and Christendom renounced incense rituals, the hunger for frankincense weakened. The desert conspired, enveloping great parts of the Frankincense Road and burying it under a sea of sand.

Spice Route to India and China

According to the great 10th century Arab traveler Abu Al Masudi, Omani sailors’ knowledge of the sea and their expertise in path finding through astronomy meant they were readily hired by merchants who wanted to travel to Canton (modern-day Guangzhou- China).

The journey from Muscat to the southern coast of India took a month, after which the ships sailed on to Sri Lanka, and then crossed the Indian Ocean and the Strait of Malacca (Malaysia), finally landing in Canton (China).

Where Omani, Italian and Portuguese sailors did a brisk trade in goods such as gold, silver, silk, jewels, textiles, white horses and copper, in addition to spices collected along the way, including cloves, black pepper, cinnamon, cardamom, and more.

Hong Kong’s name (fragant harbour) relates the reception and processing of incense and spices.

Historical accounts of the harvest of frankincense

The 13th-century Chinese writer and customs inspector Zhao Rugua wrote on the origin of frankincense, and of its being traded to China:

Ruxiang or xunluxiang comes from the three Dashi [Arab] countries of Murbat (Maloba), Shihr (Shihe), and Dhofar, from the depths of the remotest mountains. The tree which yields this drug may generally be compared to the pine tree. Its trunk is notched with a hatchet, upon which the resin flows out, and, when hardened, turns into incense, which is gathered and made into lumps.

It is transported on elephants to the Dashi (on the coast), who then load it upon their ships to exchange it for other commodities in Sanfoqi [today Dhafar]. This is the reason why it is commonly collected at and known as a product of Sanfoqi.”

Spice Route to Europe

The maritime route to Europe ran from Muscat to Aden, stopping for supplies in Mombasa before crossing Africa via the Suez, ending in Venice and Genoa.

Venetian merchant Marco Polo wrote of Dhofar in ‘The Travels of Marco Polo’ (c. 1300), stating:

Dufar is a great and noble and fine city. The people are Saracens [Muslims] and have a Count for their chief who is subject to the Soldan [Sultan] of Aden. Much white incense is produced here, and I will tell you how it grows.

The trees are like small fir trees; these are notched with a knife in several places, and from these notches the incense is exuded. Sometimes it flows from the tree without any notch; this is by reason of the great heat of the sun there. [This Dhafar is supposed to be the Sephar of Genesis, x. 30.]”

The methods of harvesting incense explained by Zhao Rugua and Marco Polo are still practiced.

Etymology and other names for Frankincense

Frankincense

The origin of the word is uncertain. The English word frankincense derives from the Old French expression franc encens, meaning ‘high-quality incense’. The word franc in Old French meant ‘noble, pure’.

“Before 1398 fraunkencense, in Trevisa’s translation of Bartholomew’s De Proprietatibus Rerum; apparently from Old French frank genuine or true, and encens.”[sic]

Frank comes from the Latin Francus, of or belonging to the Franks. Incense comes from the Latin incensum, a setting fire to, lighting, incense. Another explanation sees the word as a combination of the Old French word franc meaning “pure” or “abundant,” added to the Latin word incensum, meaning “to kindle.” Still others say that it means “the incense of the Franks,” because during the Crusades, the Franks re-introduced it to Europe.

The tree Boswellia was named after Scottish botanist John Boswell.

Stepping into a souk in Oman, one will quickly see that the country is truly a land of frankincense. Tracing its roots back thousands of years, fragrances have been integral to the people and culture of Oman, finding it’s way also onto stamps.

“Why do people buy frankincense after spending so much money on it?”

I suspected that they wouldn’t believe me, but I had to reveal the astonishing truth:

“People buy hojari so that they can take it home and burn it.”

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- Al-Kamali Reem. Frankincense, the story of a tree that continues to weep for love. https://english.alarabiya.net/views/news/middle-east/2017/05/26/Frankincense-the-story-of-a-tree-that-continues-to-weep-for-love

- Ben-Yehoshua, Shimshon & Borowitz, Carole & Hanus, Lumir. Frankincense, Myrrh, and Balm of Gilead: Ancient Spices of Southern Arabia and Judea. Horticultural Reviews. 2012.

- Bongers F, Groenendijk P, Bekele T, et al. (2019) “Frankincense in peril” Nature Sustainability 2:602–10.

- Boswellia sacra. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boswellia_sacra

- Boswellia. https://www.botmed.rocks/boswellia-spp.html

- Brendler T, Brinckmann JA, Schippmann U (2018) “Sustainable supply, a foundation for natural product development: The case of Indian frankincense (Boswellia serrata Roxb ex Colebr)” J Ethnopharmacol 225:279–86.

- Following the frankincense trail. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/90992/following-the-frankincense-trail

- Frankincense Uses. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frankincense#Uses

- Frankincense via Plants of Dhofar Guide. https://www.enfleurage.com/frankincense-via-plants-of-dhofar-guide/

- Frankincense. http://www.mei.edu/sqcc/frankincense

- Frankincense. https://www.hellenicgods.org/frankincense Thank you.

- http://www.bestiary.ca/beasts/beast149.htm

- http://www.salut-virtual-museum.org/index.php?id=32

- https://amp.theguardian.com/travel/2001/may/05/oman.guardiansaturdaytravelsection

- Frankincense medicine truth myth and misinformation. Thank you.

- https://omanisilver.com/contents/en-us/d232.html#p235

- https://seekersguidance.org/answers/general-counsel/what-is-the-place-of-frankincense-in-the-sunnah/

- https://timesofoman.com/article/97514

- Land of Frankincense. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1010-

- https://www.blackwoodconservation.org/5000-year-history/

- https://www.cntraveler.com/stories/2012-12-26/oman-luxury-perfumes-fragrances-scents

- https://www.encens-naturel.eu/en/dhofar-production-of-frankincense

- https://www.outlookindia.com/outlooktraveller/explore/story/46808/oman-history-of-omani-frankincense

- https://www.theglobeandmail.com/world/article-frankincense-omans-white-gold-loses-its-lustre-in-a-modernizing/#sidebar

- In the Cradle of Scent. https://www.cntraveler.com/stories/2012-12-26/oman-luxury-perfumes-fragrances-scents Thank you.

- Incense Route. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Incense_Route

- Incense Route. https://www.livius.org/articles/place/incense-route/

- Land of frankincense. http://www.omanobserver.om/land-of-frankincense/

- Land of Frankincense. https://web.archive.org/web/20240301042710/https://omanvisitors.com/land-of-frankincense/

- Land of Frankincense. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1010/gallery/&index=1&maxrows=12

- Land of frankincense. https://web.archive.org/web/20250320091336/https://www.worldheritagesite.org/list/Land+of+Frankincense

- Mackintosh-Smith T.. Scents of Place. Frankincense in Oman. https://archive.aramcoworld.com/issue/198706/old.scent.new.bottles.htm Thank you.

- Oman History: Explore the ancient Omani trading routes. https://timesofoman.com/article/100895/HI/This-Weekend/Oman-History-Explore-the-ancient-Omani-trading-routes

- Oman legends that live on. http://www.omanobserver.om/oman-legends-that-live-on/

- Oman the land of frankincense.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses 4.192–270

- Replicating the slightly plantable gifts of the magi in the garden. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/08/garden/replicating-the-slightly-plantable-gifts-of-the-magi-in-the-garden.html?_r=1

- Salalah Oman. Pics from https://oilygurus.com/farms/salalah-oman/

- Smith William. A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. 1880.

- The frankincense tree. https://web.archive.org/web/20171129222134/http://timesofoman.com:80/extra/frankincense/phone/the-frankincense-tree.html

- The Great Trade Routes: The Scent Route. https://thejourneytotheeast.com/the-scent-route-europe-asia/

- The land of Frankicense. https://www.herbalhistory.org/home/the-land-of-frankincense/

- What is frankincense. https://www.learnreligions.com/what-is-frankincense-700747