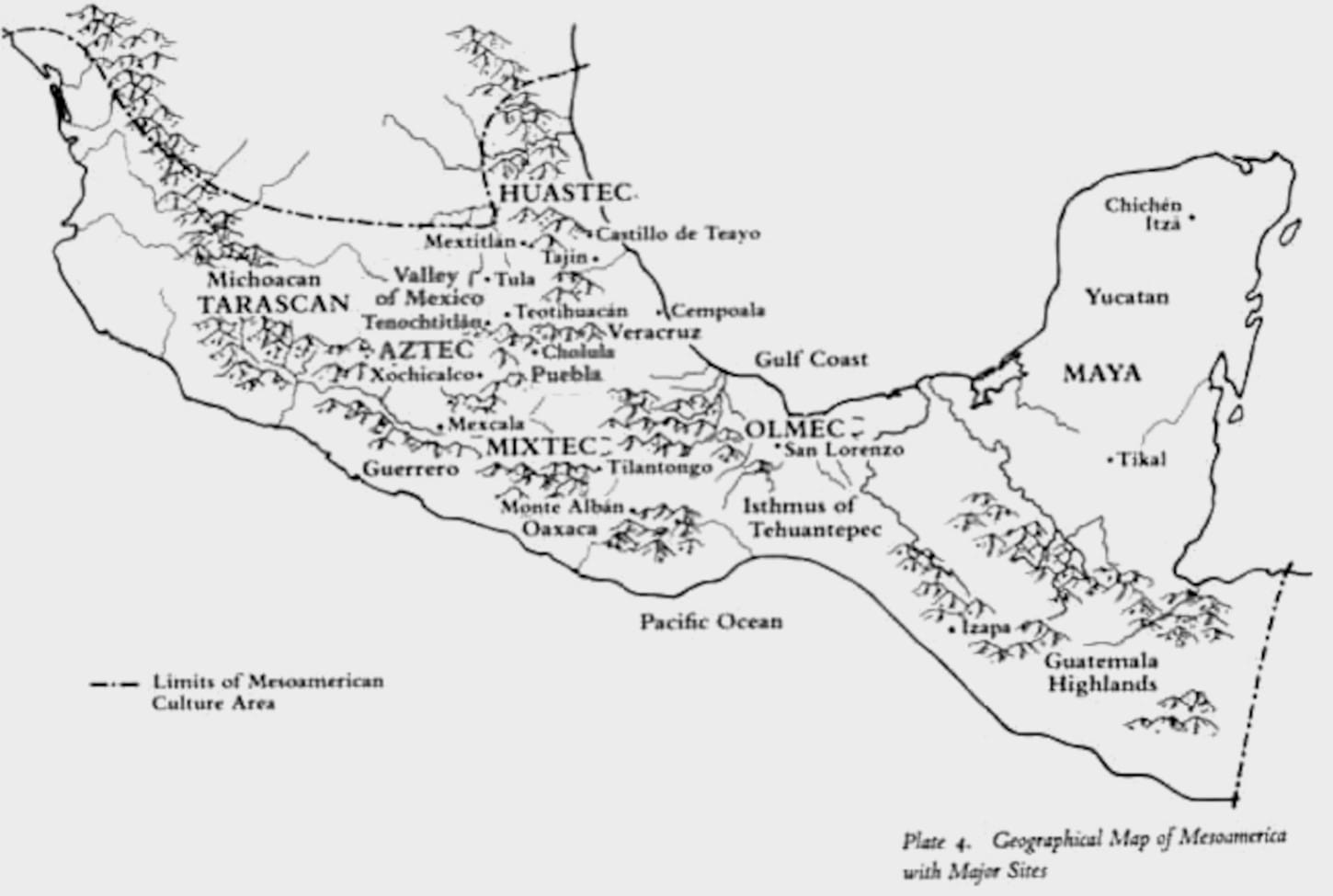

Discover historical and mythical origins of Cacao in Mesoamerica. Cacao – or traces of the compounds theobromine and caffeine – have been found in archaeological deposits from a number of civilizations, including the Olmec, Maya, Toltec and Mexica/Aztec in Mexico and Guatemala, and the Ancestral Pueblo Culture at Chaco Canyon in New Mexico.

In this Article

A brief history of Cacao

Theobroma cacao in Mesoamerica

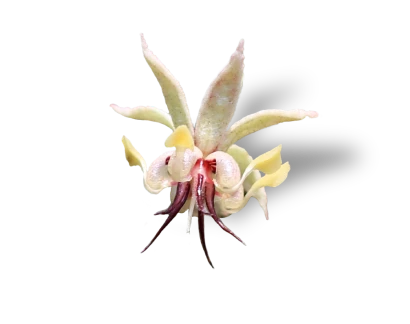

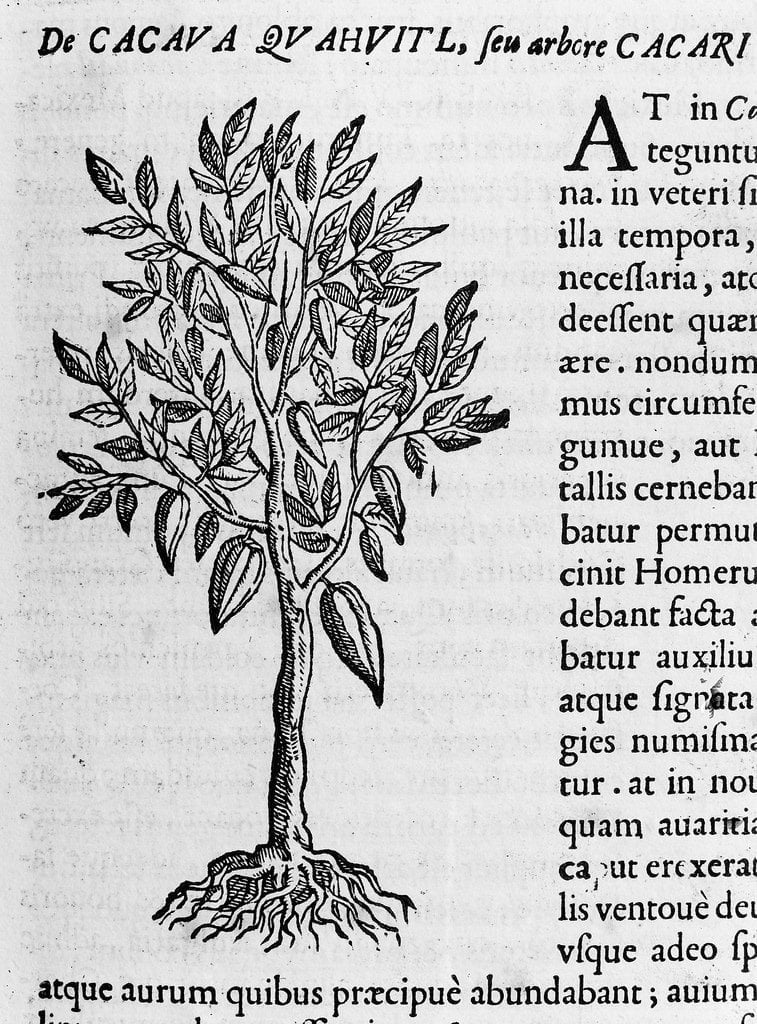

Theobroma cacao is the modern scientific name for chocolate, and it is indeed fitting, for Theo “of Gods” broma “food” in Greek it means “food of the gods.” The tree originated in the Upper Amazon where it was domesticated ca. 5450 to 5300 BC.

From this center of origin, cacao was dispersed and cultivated in Mesoamerica as early as 3800 to 3000 BC After the European conquest of the Americas (the 1500s), cacao cultivation intensified in several loci, primarily Mesoamerica, Trinidad, Venezuela, and Ecuador.

Cacao grows as pods on the Theobroma cacao tree. This plant likely originated in the Amazon Basin, but the earliest evidence of processing cacao is among the Mokaya culture and Olmec civilization in Mexico.

Cacao is an indicator of cultural development in Mesoamerica

Just like maize, beans and squash, cacao is indigenous to Mesoamerica, and has been cultivated from wild species. But cacao is not a staple crop that provides nutrients necessary for basic survival, rather it is a luxury, that provides delicious theobromine for the nervous system at the expense of a laborious process of cultivation and processing.

This means that the presence of cacao demonstrates that a culture has moved beyond the stage of bare necessities and generated a surplus. The generation of surplus in turn marks the beginning of class division and hierarchy, and a complex division of labour – the social signs archaeologists associate with the phenomenon we call civilization.

Therefore, signs of the consumption of cacao is a kind of litmus test for when and where Mesoamerican civilization can be said to have begun.

Cacao – or traces of the compounds theobromine and caffeine – have been found in archaeological deposits from a number of meso-american civilizations. At first, only the cacao pulp was used and humans began trading it, yet it was until 1800 BC that the inhabitants of this regions discovered how to turn the cacao seeds into chocolate.

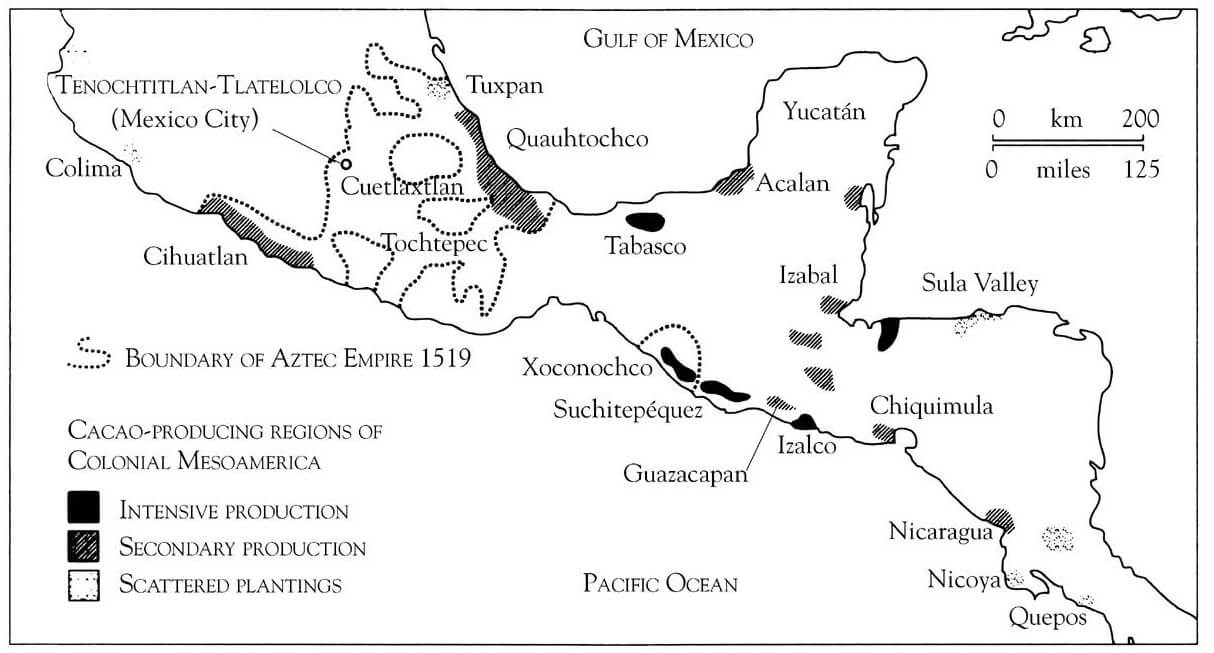

“The upper class nobility and gentry of Mexico were great consumers of chocolate, and the best cacao was that of Soconusco.

As a kind of pan-Mesoamerican money, cacao gained even more prestige. It was certainly an economic motivation, not desire for justice, which prompted Ahuitzotl to take Soconusco”

Coe

The archaeological evidence on the usage of cacao in the form of a liquid drink points to the Mokaya culture during the “Barra” ceramic phase (1900-1700 BC), predating the Olmecs, in which their elaborate pottery is hypothesized by scholars to have been used for display of valued drinks, rather than cooking, at social gatherings and feasts.

Pre-Olmec (ca. 1650 BC) people in the Gulf Coast area were also actively involved in the production and consumption of chocolate and consequently the Olmec were also fully familiar with cacao.

By the time the Olmec civilization rose (1500-400 BC) in the lowlands of the Mexican Gulf Coast, the preceding Mesoamerican inhabitants had already made chocolate well known to them.

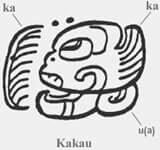

There is evidence found on Olmec writing (i.e. Cascajel Tablet) of the word /kakawa-tl/ in Nahuan or Uto-Aztecan which is yet to be fully decoded. According to other linguists they spoke the Mixe-Zoquean (proto-Mije-Sokean) which introduced the word to describe cacao as “kakaw” (originally pronounced kakawa).

Because the word has two different proposed etymologies, one that goes back to the deep past of the Mixe-Zoquean language family of the Olmecs, and one that traces the word to the earliest Nahuan language, the language of the Aztecs. The debates pitting the Nahuas and the Olmecs against each other as being the “founders of Mesoamerican civilization”.

During the Late Pre-Classic, the Olmec – derived Izapan culture located in the heart of the Soconusco region might been the ones who spread the process of making chocolate to the rest of Mesoamerica (Yucatan, Tabasco, Gulf of Mexico region, and Guatemala highlands and northern lowlands).

Izapa, lies in the midst of Soconusco, in that very region in which chocolate seems to have been born a millennium earlier. They crushed the cocoa beans, mixed them with water and added spices, chillies and herbs. They began cultivating cocoa in Mexico.

In the Popol Vuh (the sacred book of the Quiché/K’iche Maya), cacao first appears in the form of seeds in market settings, but not as the gruel and drink that it came to be and the Izapans were integrated in the Maya creation myths by foods like cacao which the gods found in the Mountain of Sustenance.

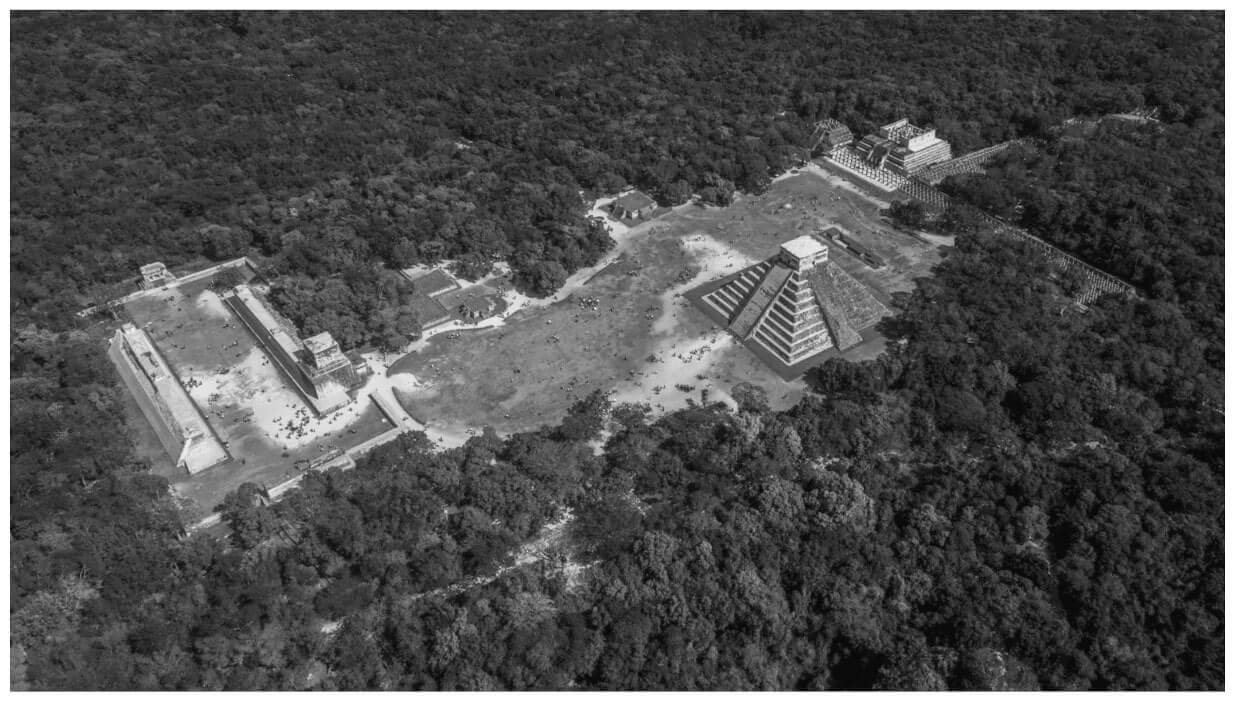

Many of these Popol Vuh narratives are present in Izapan carvings on stone stela at Izapa and found on the temple walls in Chichén Itzá. Iconographic images from Classic period ceramics and stoneware reveal a significant and continuing connection between cacao and maize in Popol Vuh.

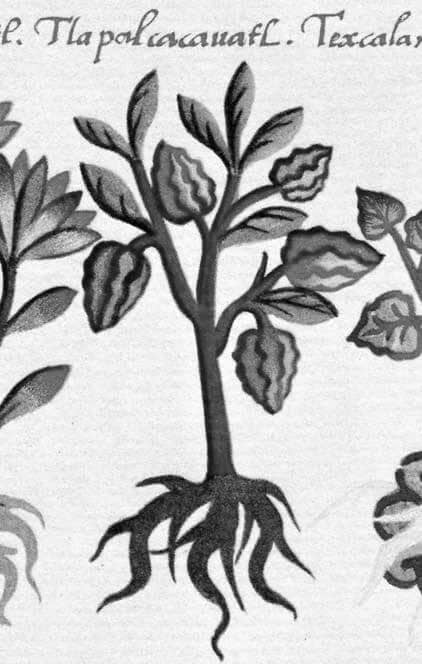

Over time, the Mayans and Aztecs developed successful methods for cultivating cocoa as well. The cocoa bean was used as a monetary unit and as a measuring unit, 400 beans equaling a Zontli and 8000 equaling a Xiquipilli.

During their wars with the Aztecs and the Mayans, the Chimimeken people’s preferred method of levying taxes in conquered regions was in the form of cocoa beans.

By the 10th century C.E., a new people had appeared on the Mesoamerican stage: the Toltecs. Later Mexica/Aztec accounts describe them as a race of supermen, capable and skilled in the arts, and say that it was they who had passed on high civilization to the Aztecs who eventually replaced them as the dominant power in central Mexico.

Not only did the Toltecs vanquish the Putún Maya (whom they called the “Olmeca,” just to confuse us!) as the rulers of the Cacaxtla region, but they seem to have journeyed across the Gulf of Mexico to take over the whole Yucatán Peninsula, which they governed from their eastern capital, Chichén Itzá.

Much of Mesoamerica fell under the pax tolteca, ushering in the Post-Classic period, which ended with the Spanish invasion. The Toltec reach extended far beyond the northern frontier of Mesoamerica, even beyond the southern borders of the United States of today, as exciting new research has proved.

MYTH : On the creation of the cacao tree

The Popul Vuh manuscript is the Sacred Book of the Quiché/K’iche Maya. The document – along with Quiché/K’iche oral traditions – was discovered and summarized in Latin during the 16th century by Father Francisco Ximénez, a Dominican priest, who served in the Guatemala highlands at Santo Tomas Chichicastenango. The document reflects the cosmology, religious practices, and history of the Quiché/K’iche Mayan.

According to Mayan religious beliefs, cacao had a divine origin. In the creation story recorded in the text known as the Popol Vuh, cacao is one of the precious substances that is released from “Sustenance Mountain” (called Paxil in the Popol Vuh, meaning “broken, split, cleft”), along with maize (corn), from which humans are made, at the time just prior to the fourth or present creation of the world.

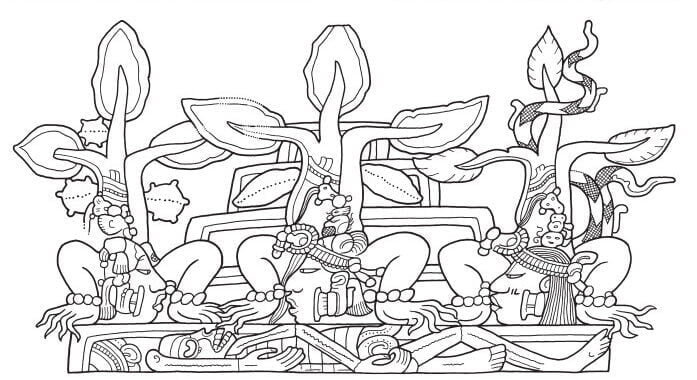

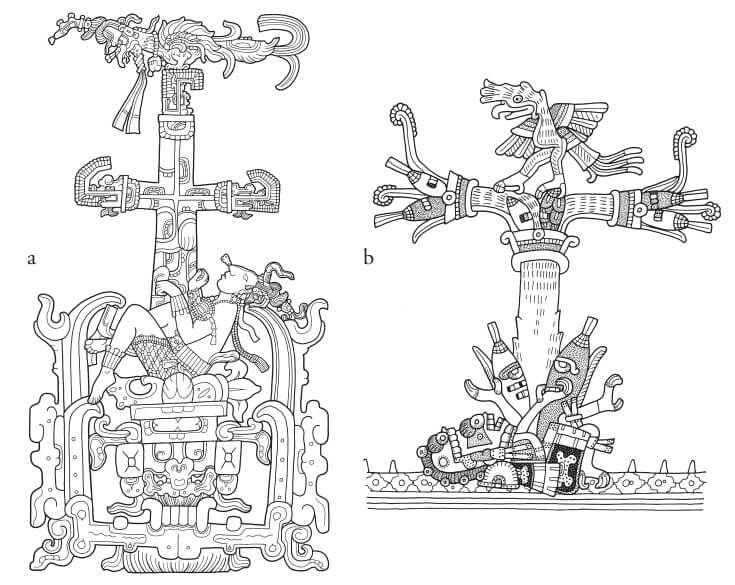

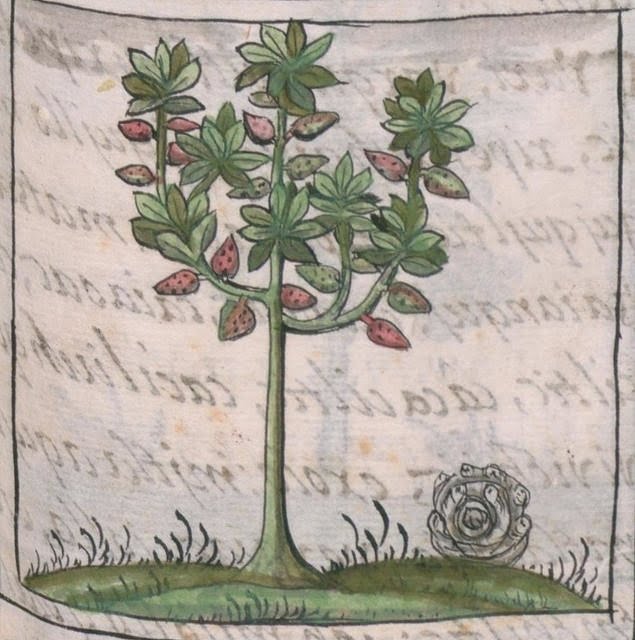

Of the three tree figures, the central one sprouts cacao pods, the one on the left bears a spiked fruit that may be guanabana (Annona muricata L.), and the one on the right has a snake-like design that may represent a vine or creeper.

Excerpted from Martin Simon. “Cacao in Ancient Maya Religion: First Fruit from the Maize Tree and Other Tales from the Underworld,” in Chocolate in Mesoamerica: a Cultural History of Cacao. 2006.

Before this, the cacao tree belonged to the realm of the Underworld lords, where it grew from the body of the sacrificed god of maize, who was defeated by the lords of the Underworld in an earlier era.

MYTH: The Hero Twins

The first set of twins, sons of the old couple who have created the universe, meet their untimely end in Xibalbá, the Maya underworld, where they are beheaded by the sinister lords of that dreaded place. The severed head of one of that unlucky pair (now known to be the Maize God) is hung up in a tree – said to be a calabash tree in the story, but pictured as a cacao tree on a Classic Maya vase.

One day this disembodied head magically impregnates the daughter of a Xibalban ruler as she holds up her hand to it.

The maiden Xkik’ encounters the skull in the tree:

“What’s the fruit of this tree? Shouldn’t this tree bear something sweet?

They shouldn’t die, they shouldn’t be wasted. Should I pick one?” said the maiden.

And then the bone spoke; it was here in the fork of the tree:

“Why do you want a mere bone, a round thing in the branches of the tree?” said the head of One Hunahpu when it spoke to the Maiden.

“You don’t want it,” she was told.

“I do want it,” said the maiden…

Xkik’ reaches up to touch the fruit, the skull of Hun Hunahpu, and he spits into her hand.

He tells her that she would then become the mother of his twins, and that she must leave the underworld. With the help of owl messengers, Xkik’ escapes her impending sacrifice after her father and the Lords of Death discover her pregnancy. The owls return her safely to the surface of the earth, where her children, the Hero Twins, Hunahpu and Xbalanque, are born.

Following a series of exploits reminiscent of the Labors of heroes, the Hero Twins go on to defeat Xibalbá and its ghastly denizens, a true Harrowing of Hell. They also defeat the gods of the underworld in deadly ballgames.

Their final task is to resurrect their slain father, the Maize God. This having been accomplished, they rise to the sky in glory as the sun and the moon.

The story deals in symbolic form with the burial (that is, the planting of the seed), growth, and fruition of maize, the Maya – and Mesoamerican – staff of life.

At a later time, the maize god was resurrected by his sons the Hero Twins, who were able to overcome the Underworld gods. Thereafter, human life became possible, once the location where the grains and maize were hidden was located and its bounty released by the rain god Chaak and the deity K’awil, who represents both the lightning bolt and the embodiment of sustenance and abundance.

The deities of importance to this story include the maize god Nal, Chaak, K’awil, and various Underworld lords, including the paramount death god (named Kimil in some sources) and a deity known by the designation God L. God L played various roles in Maya mythology, representing a merchant deity, an Underworld lord, and a Venus god.

The Maize God and Cacao

Sources from across Mesoamerica agree that the sacrificial death of the Maize God at harvest time – for the Maya at the hands of Underworld deities – was followed by his burial in a cave within a mountain. At least part of his soul or spirit left his body and rose to the heavens. In the Popol Vuh it is the Hero Twins who ascend to become the sun and moon, but in earlier versions it may be the Maize God whose apotheosized spirit joins or forms these celestial bodies.

His abandoned corpse, gives rise to trees bearing edible fruits and seeds. This takes place while he is entombed within Sustenance Mountain and symbolizes the process of germination, which occurs out of sight underground, so Martin.

The themes of decomposition and transformation on the Palenque sarcophagus resonate strongly with the mythology of Central Mexico and a description in the sixteenth-century Histoyre du Mechique. Here the Maize God Centeotl buries himself in the floor of a cavern and from his body grows corn, as well as the fruits and seeds of other useful plants.

Cross culturally, trees supply a rich collection of metaphorical meanings appropriate to generational descent, and in Maya ideology they evidently constitute a bridge between death and rebirth. It is the Maize God’s manifestation as a fruit tree that allows him to pass on his procreative seed and to eventually triumph through the heroic deeds of his offspring.

God L

The cacao of the Maize Tree grows in the domain of the Underworld’s paramount lord, God L, where it is evidently the source of his wealth. He enjoys the good life, drinking and trading, unaware of his forthcoming punishment at the hands of the next generation.

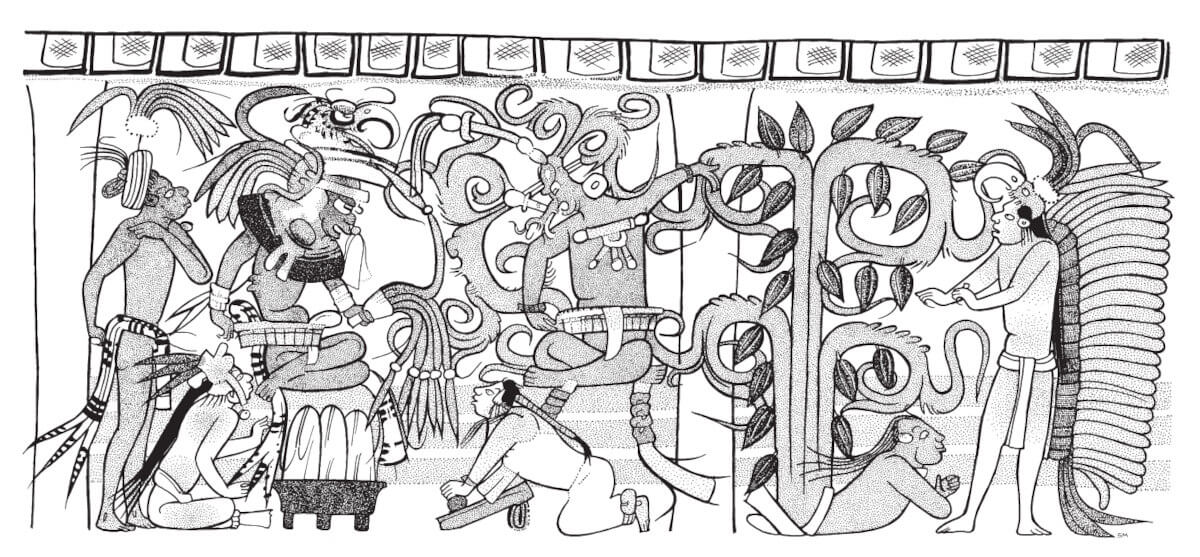

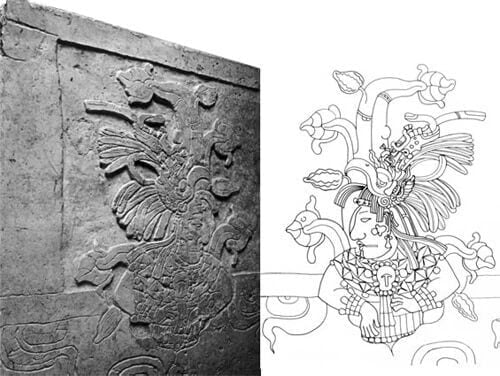

There is a direct connection between the images at Temple of Owls in Chichen Itza and vessel K631, both showing cacao as a sacred tree which is related to the Underworld and God L and taken to earth for the sustenance of humankind. God L is related with cacao wealth as well as having ties to commerce and long-distance trade (depicted in murals at Cacaxtla, Mexico and narrative in the Popol Vuh)

Red Temple, Cacaxtla, Mexico. Drawing by Simon Martin after a photograph by Enrico

Ferorelli in M. E. Miller and S. Martin 2004:Figure 24.

God K’awiil and Cacao or K’awiil’s flight from the Underworld

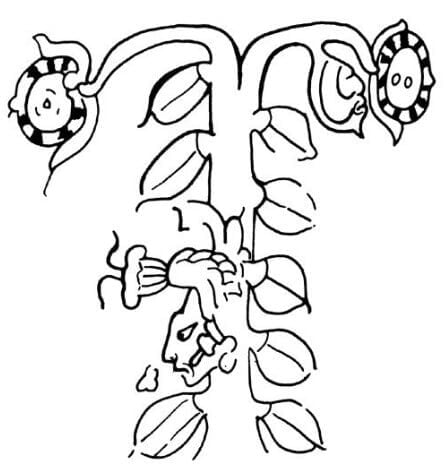

Late Classic or Postclassic period. Temple of the Owls, Chichen Itza, Yucatan, Mexico. Drawing by Simon Martin after a photograph by T. A. Willard in Winning 1985:Figure 95.

This vividly painted panel within the structure depicts the Quiché/K’iche Maya god K’awiil emerging from a serpent holding a plate with offerings possibly containing cacao, and jade ear spools. An incomplete date is mentioned in the glyphic text. Sky bands frame the sides of the panel.

The Quiché/K’iche Maya god K’awiil, is the lord of sustenance and of royal descent. The god’s expression of “rescuing” the seeds from the cenote and their “gifting to heaven and earth” in this scene depict the significance of the spiritual value of cacao.

Beyond being a status symbol, cultivation of cacao in cenotes (natural cavities) also indicates the spiritual importance of cacao. Having the origins of cacao not on Earth but in the Underworld which then was taken to heaven and earth.

Cross culturally, trees supply a rich collection of metaphorical meanings appropriate to generational descent, and in Maya ideology they evidently constitute a bridge between death and rebirth. It is the Maize God’s manifestation as a fruit tree that allows him to pass on his procreative seed and to eventually triumph through the heroic deeds of his offspring.

There is also a link between lightning (K’awiil) and human sustenance (Maize God) in central Mexican mythology (Codex Chimalpopoca) as well as Quiché/K’iche Maya accounts which are portrayed in vessel K631 where K’awiil carries a cacao sack with “kakaw” glyphs (a).

The task of rescuing cacao and all the other Cacao in Ancient Maya Religion foods that will sustain humanity falls to the lightning bolt, K’awiil. His special power was to penetrate different worlds, with the awe-inspiring phenomenon of nature’s electromagnetism making him a great energizer and catalyst (there are interesting overlaps here with scientific understandings, in which lightning fixes nitrogen – nature’s fundamental fertilizer – in the soil, and electricity is harnessed to power all manner of different processes).

The story builds to a climax with the Maize God’s rebirth. On various painted vessels he is dressed in jade jewels and quetzal feathers symbolizing maize foliation and watered by the Hero Twins, before emerging from the cleft made by Chaak and K’awiil.

MYTH: Axis Mundi, cacao is the World Tree

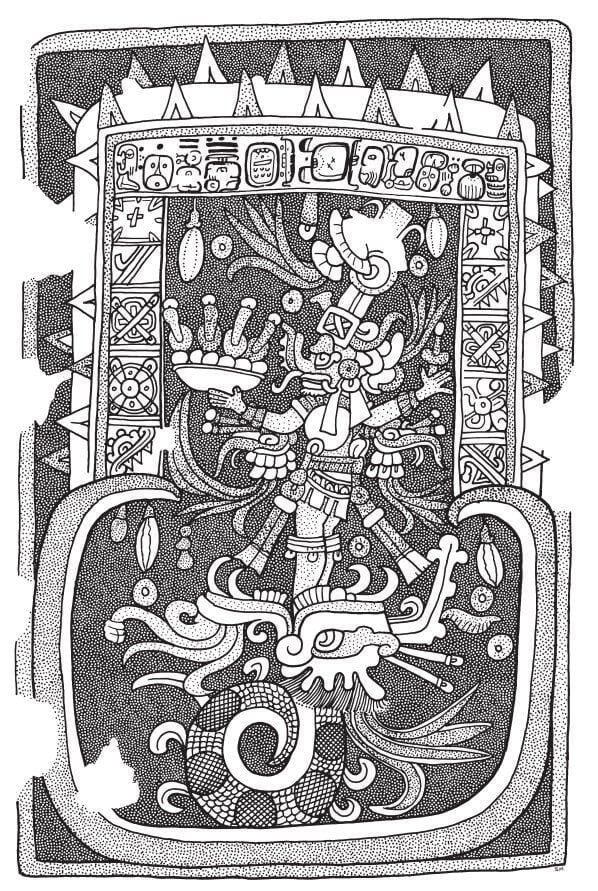

The Maize God’s realization as a World Tree or axis mundi is the ultimate expression of his resurrection, with his ascent to the sky implicated in a reconfiguration of the universe, the creation of humanity, and an end to earthly darkness and chaos.

The best-known anthropomorphic trees in Maya art are those that ring the sarcophagus of Pakal of Palenque, Mexico, inside a tomb chamber deep within the Temple of the Inscriptions – a symbolic cave within a mountain – the great slab of its lid shows a reclining Pakal wearing the net kilt of the Maize God, with the fiery torch of the lightning deity K’awiil set in his forehead (Figure a).

The World Tree is a mythical arbor marked with TE’ ‘tree/wood’ signs and bearing bejeweled, serpent-headed flowers. Similar ideas are found in certain Maya communities today, where trees are planted over newly laid graves as tokens of future resurrection.

J. Eric S. Thompson, 1970, noted the relationship of the lid scene to those in the Central Mexican codices Borgia and Vatican B in which recumbent deities give rise to directional World Trees. Here he is immolated in an offering brazier so that new life might take his place; the potency of fire in trans-formative events is a recurring theme in Mesoamerican belief (Figure b).

On the sarcophagus sides, ten fruit-laden saplings emerging from cracks in the ground can be identified from the shape of their progeny as cacao, guayaba, avocado, zapote, and nance.

Each tree is fused with a human portrait, identified by its headdress and adjacent glyphic caption as a particular forebear of Pakal (with his parents shown twice, on either end of the sarcophagus). On both of its appearances the cacao tree is associated with Pakal’s deceased mother, Ix Zac K’uk’, ‘Lady Resplendent Quetzal,’the person believed to represent his closest blood connection to the ruling line of Palenque.

This great life and death cycle was no remote paradigm for the Maya elite but one that seems to have made even a sip of chocolate a sacramental act.

More particularly, the images on the Dumbarton Oaks bowl, the Berlin vase, and the Pakal’s sarcophagus from Palenque can be recognized as pious celebrations of the Maize God epic and methaphorically as purposeful expressions of personal redemption. The lords so commemorated emulate the corn deity on his triumphal journey through the purgatorial Underworld and beyond to an ultimate, deeply desired, union with the cosmos, Simon Martin suggests.

Quetzalcoatl and cacao

Cocoa was a symbol of abundance. It was also used in religious rituals dedicated to Quetzalcoatl, the god responsible for bringing the cocoa tree to man.

Cocoa production advanced as people migrated throughout Mesoamerica but consumption of the drink remained a privilege for the upper classes and for soldiers during battle. By this time, the reinvigorating and fortifying virtues of cocoa were becoming widely recognized and embraced.

The cacao bean was so significant to the local cultures that it was used as a currency in trade, given to warriors as a post-battle reward, and served at royal feasts.

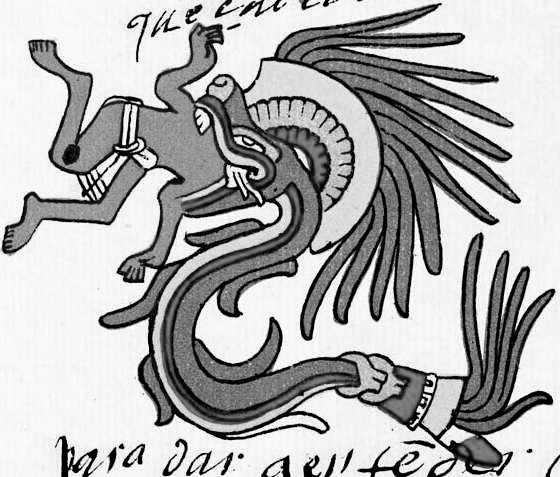

The Feathered Serpent Quetzalcóatl

The earliest known documentation of the worship of a Feathered Serpent occurs in Teotihuacan in the first century BC, within the Late Preclassic to Early Classic period (400 BC – 600). In the Postclassic period (900–1519), before the Spanish arrived, the most important worship center was Cholula, where a large pyramid was dedicated to Quetzalcoatl-worship.

Public domain, edited.

In Aztec culture, depictions of Quetzalcoatl were fully anthropomorphic. Quetzalcoatl was associated with the wind-god Ehecatl and is often depicted with his insignia: a beak-like mask.

His Mayan name is Kukulcán and Gukumatz, names that also roughly translate as “feathered serpent” in different Mayan languages.

Quetzalcóatl in Teotihuacán

The Toltec peoples settled in the Central Valley of Mexico during the 10th century of the Common Era. Monuments to their greatness still stand at their religious and commercial center Teotihuacan, approximately 60 kilometers northeast of modern Mexico City.

The feathered serpent stands as a symbol of the creation of life. Representations of a feathered snake occur as early as the Teotihuacán civilization (3rd to 8th century CE) on the central plateau.

Public domain, edited.

At that time Quetzalcóatl seems to have been conceived as a vegetation god – an earth and water deity closely associated with the rain god Tlaloc.

With the immigration of Nahua-speaking tribes from the north, Quetzalcóatl’s cult underwent drastic changes. He bacame the serpend god, Quetzalcóatl, (from Nahuatl quetzalli, “tail feather of the quetzal bird [Pharomachrus mocinno],” and coatl, “snake”).

The subsequent Toltec culture (9th through 12th centuries), centered at the city of Tula, emphasized war and human sacrifice linked with the worship of heavenly bodies.

Quetzalcóatl became the god of the morning and evening star, and his temple was the centre of ceremonial life in Tula.

TOLTEC MYTH: Cacao, the gift of Quetzalcóatl or The good people of Tollan (Tula)

English:

Quetzalcóatl and the good people of Tollan (Tula)

Once upon a time Quetzalcóatl, the good of knowledge, descended to earth with gifts for his Toltecs: corn, beans and yucca, so they will never lack any food. The Toltecs spend their free time studying. In time they were wonderful architects, artists, masons and delicate moulders of clay.

God Quetzalcóatl, who loved them deeply gave them the gift of a very special plant. This plant had been jealously guarded by the other gods because they extracted a drink which was reserved only for the gods themselves. Quetzalcóatl stole the small bush with dark red flowers and planted the bush and asked Tláloc to feed it with water and Xochiquetzal to tend to it and make it beautiful with flowers.

The little tree flowered incessantly and Quetzalcóatl picked up the pods, roasted the kernels and taught the Toltec women to grind them into a fine powder. The women then mixed the powder with water from their jars and whipped it into a frothy drink which they called chocolatl. In the beginning it was only drunk by priests and royalty.

The Toltecs became so wise, so learned in the arts and sciences and so prosperous that the gods became jealous at first, and then, angry when they discovered that their chocolatl had been stolen from them. They vowed to make war on Quetzalcóatl and the Toltecs.

One day one of the gods disguised himself as a merchant, and offered Quetzalcoatl a drink called Tlachihuitli which he promised will help him forget his troubles and sorrows. The god became quickly drunk, that he felt so much dishonour and shame, that he decided to leave forever.

But at his departure, just before he left, he noticed that all the cocoa plants had dried up. Before he left the land never to return, he placed unto the ground in Neonalco (Tabasco), the last seeds of cacao he had left in this hand. The seeds, with time, flourished and became the last gift of the god and reached until our days.

Spanish:

Quetzalcóatl and the good people of Tollan (Tula)

Quetzalcóatl era considerado para los mayas como el Dios de la Sabiduría. Cuenta la leyenda que un día descendió con los toltecas haciéndoles algunos regalos: por ejemplo, les hizo dueños del frijol, del maíz y de la yuca, brindándoles la posibilidad de que nunca les faltará ningún alimento.

Gracias a ello pudieron emplear sus horas en estudiar, convirtiéndose así en grandes y maravillosos escultores, artesanos y arquitectos. Poco después, como muestra de su amor hacia los toltecas, decidió regalarles una planta que anteriormente Quetzalcóatl había robado a sus hermanos.

Sustrajo el arbusto con hojas de color rojo y la plantó en los campos de tula. Así, solicitó a Xochiquetzal que la adornara con sus flores y a Tláloc que la alimentara con su lluvia.

Con el paso del tiempo el arbusto creció y comenzó a dar sus frutos. Fue así como le enseñó a recogerlos, tostarlos, molerlos y batirlos con agua en jícaras. Fue así como obtuvieron el Chocolate, una bebida maravillosamente mágica que solo podían disfrutar los nobles, los sacerdotes y los dioses.

Pero el pueblo empezó a consumir esta rica bebida, convirtiendo así a los toltecas en artistas y constructores sabios, gracias a las cualidades estimulantes y reconstituyentes del chocolate. Esto despertó la envidia y la furia de los dioses.

Un día uno de los dioses se disfrazó de mercader, y le ofreció a Quetzalcóatl una bebida llamada tlachihuitli con la que le prometió olvidar sus problemas y penas. El dios se embriagó profunda y rápidamente, y sintió tanta deshonra y vergüenza hacia sus hermanos que decidió marcharse para siempre.

Pero a su partida, justo antes de marcharse, se percató que todas las plantas del cacao se habían secado. Fue cuando arrojó las últimas semillas de cacao en Neonalco (actual Tabasco), que finalmente florecieron bajo su mano y llegaron hasta nuestros días.

An important body of myths describes Quetzalcóatl as the priest-king of Tula, the capital of the Toltecs. He never offered human victims, only snakes, birds, and butterflies. But the god of the night sky, Tezcatlipoca, expelled him from Tula by performing feats of black magic.

Quetzalcóatl wandered down to the coast of the “divine water” (the Atlantic Ocean) and then immolated himself on a pyre, emerging as the planet Venus. According to another version, he embarked upon a raft made of snakes and disappeared beyond the eastern horizon.

VARIANT: QUETZALCÓATL AND THE GOOD PEOPLE OF TOLLAN (TULA)

The gods felt sorry for all the work that the Toltec people had to perform and decided that one of themselves should go down to the Earth to help humans by teaching the sciences and the arts. Thus it was that Quetzalcóatl took the form of a man and descended on Tollan, the city of workers and good men.

And it was done. Quetzalcóatl loved all mankind and gave them the gift of a plant that he had taken from his brothers the gods, who jealously guarded it.

He took the small bush which had red flowers, hung on branches which had long leaves, and were sloped towards the ground, which offered up its dark fruit.

Thus it was that Quetzalcóatl planted the tree in the fields of Tollan, and asked Tlaloc to nourish it with rain, and Xochiquetzal to decorate it with flowers, and the little tree gave off fruit and Quetzalcóatl picked the pods, had the fruit toasted, and taught the women who followed the man’ s work to grind it, and to mix it with water in pots, and in this manner chocolate was obtained.

The Mexica/Aztecs had a very similar myth – that the domestic plants which were to sustain human life had been hidden in a mountain, the “Mountain of Sustenance”, and had to be brought to the earth’s surface by divine intervention (in the Aztec case, the great god Quetzalcoatl instructed the ants to bring out maize seed).

MEXICA/AZTEC MYTH: THE FAITHFUL MEXICA PRINCESS

The Mexica/Aztecs were relative latecomers to the Central Valley of Mexico, arriving during the mid – 13 century CE from their mythical home of Aztlan, an undefined region to the north.

Their arrival precipitated great upheaval within the valley and the people ultimately settled ca. 1325 on an island in the midst of Lake Texcoco, where they would establish the great city of Tenochtitlan. The Mexica relate how cacao came to humans.

A Mexica princess guarded the treasure that belonged to her husband, who had left home to defend the empire. While he was away she was assaulted by her husband’s enemies who attempted to make her reveal the secret place where the royal treasure was hidden. She remained silent and out of revenge for her silence they killed her.

From the blood shed by the faithful wife and princess, the cacao plant was born, whose fruit hides the real treasure of seeds – that are bitter like the suffering of love; seeds – that are strong like virtue; seeds – that are lightly pink like the blood of the faithful wife.

And it was that Quetzalcóatl gave to humans the gift of the cacao tree for the faithfulness of the princess.

The Inca and cacao

In the ancient ruins of what is today Bolivia and Peru, archaeologists have found remains and pottery on which cacao is depicted. These ceramic vessels were used in religious ceremonies and funeral rites in these regions of South America.

Incas believed that each crop had a protective spirit named Conopas. Conopas were the best proceeds of the crop which was set aside in order to offer it to the gods during a special ceremony. They believed that the offering would maximize their yields.

For instance, the conopa of cacao would be called Mamacacao, of maize saramama (mother of the maize), of potato, Papamama and of coca, Cocamama.

Cacao and other food plants, such as potatoes, maize and peanuts (of tropical South American origin) were sometimes combined with human beings by the Mochica or Moche (100 CE – 700 CE) potters, as in the picture of the Cacao Woman or the Cacao Mother.

Mama cacao is a woman wrapped in the cacao fruit breastfeeding an infant with earplugs. In the Andean world, drinking water from a cacao shell is associated with the increase of breast milk production.

SYNCRETISM: Christ and Cacao

TREE OF KNOWLEDGE – TREE OF SIN

Contemporary Quiché/K’iche Mayans relate that their ancestors considered the cacao tree especially revered and still call the tree today the tree of sin and knowledge. While conducting field work in northern Guatemala during August 2000, Dr. Victor Montejo met with Quiché / K’iche elders who told him how cacao had come to humans.

The cacao tree originally was just like any other tree in the forest. Then, Jeusu Christ appeared to us and was persecuted by His enemies. Christ fled and took refuge in the forest. To escape His enemies Christ hid under a cacao tree. He touched the trunk and the tree immediately blossomed and covered Him with white flowers, so that His enemies would not find Him.

Because of the tree’s help, Christ told the tree that it would be blessed, and that its cacao fruits would be used for beverages in ceremonies. This is why it is called tree of knowledge.

Quiché/K’iche respondents told Montejo that the cacao tree also is called awas che ’ (tree of sin). The reason for this designation stems from the dual function of the tree as being sacred and a source for food. And because of its former use as currency among Quiché/K’iche peoples when cacao beans were used as a medium of exchange and ultimately became equated with money.

Quiché/K’iche respondents related that humans initially had received the gift of cacao from Christ. In order to perpetuate Christ’s memory the ancestors were instructed that cacao was to be drunk only during religious ceremonies.

The Quiché/K’iche elders then related:

There came a time when we did not know that the original gift and meaning of cacao was to serve as a tree of knowledge, and [through the centuries] mankind sinned and we did not drink cacao to honour Christ, but used the beans as money. Therefore, it became a tree of sin [awas che’].

According to Montejo, other Quiché/K’iche he interviewed claimed the tree that protected Christ was a different, unnamed tree.

A variation of the Quiché/K’iche cacao tree Christ tradition initially was published in 1967 and reviewed recently in a monograph on chocolate in Mesoamerica, as told by the contemporary Quiché/K’iche Mayan of Chichicastenango.

When Christ first asked for help, the cacao tree initially responded, with some trepidation, that it was not capable of the task and that “ our lord Manuel Lorenzo [the whirlwind] ” will shake the tree. Christ, in response, told the tree that if it helped him, it would be remembered forever, but that if it did not he would destroy it at Judgment day. He also offered to bless the tree in heaven, but the tree replied that it could not go to heaven because its roots were stuck down into the ground.

Christ told the tree that he would put it

“into the clouds and mists of heaven”

bringing these to the tree if he could not bring the tree to them and said that the tree would thrive along the coasts. Then the cacao tree covered Christ in white blossoms, sheltering him from the sun and his enemies.

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- A concise history of chocolate. https://www.c-spot.com/atlas/historical-timeline/

- Anonymous, The Vertues of Chocolate East-India Drink, one page. This apparently was taken out of Antonio Colmenero, Chocolate: Or, An Indian Drink, translated into English by James Wadsworth.

- Clarence-Smith William Gervase. Cocoa and Chocolate. 1765–1914. 2000.

- Coe Michael D. Coe Sophie Dobzhansky. The true history of chocolate.

- Colmenero de Ledesma, A Curious tretise on the nature and quality of chocolate. Trans. Don Diego Vades-forte [James Wadsworth].1640.

- Colmenero de Ledesma. Curioso Tratado de la naturaleza y calidad del chocolate. Madrid, 1631. (Latin 1644)

- Fao infographik http://www.fao.org/resources/infographics/infographics-details/en/c/277756/

- Grivetti Louis E., Shapiro Howard-Yana. Chocolate – History, Culture, Heritage.

- Grivetti Louis Evan & Shapiro Howard-Yana. Chocolate: History, Culture and Heritage. 2009. [NOTE: this book offers extensive descriptions and translated excerpts from primary documents describing Early New Spain chocolate recipes.]

- Grofe Michael J. The Recipe for Rebirth: Cacao as Fish in the Mythology and Symbolism of the Ancient Maya.

- https://foodtimeline.org/foodmaya.html#hotchocolate

- https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/maya/chocolate/history-and-uses-of-cacao.

- Kaufman Terrence. Justeson John. The History of the word for cacao in ancient Mesoamerica. 2008. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/ancient-mesoamerica/article/history-of-the-word-for-cacao-in-ancient-mesoamerica/FE4A2AE4F9D0C1EDCFB583DB315907E4

- Levin Carole. How Sweet It Is: From the Mountains of Mexico to the Streets of York. Torch Magazine. 2018. http://www.ncsociology.org/torchmagazine/v913/Levin.pdf

- Martin Simon. “Cacao in Ancient Maya Religion: First Fruit from the Maize Tree and Other Tales from the Underworld,” in Chocolate in Mesoamerica: a Cultural History of Cacao, ed. Cameron L. McNeil (University Press of Florida, 2006).

- Maxwell Kenneth A Sexual Odyssey: From Forbidden Fruit to Cybersex. New York: Plenum.1996.

- McNeil Cameron L. Chocolate in Mesoamerica A Cultural History of Cacao. 2006.

- Moreiras, Diana K. Thinking and Drinking Chocolate: The Origins, Distribution, and Significance of Cacao in Mesoamerica. 2010.

- Sahagún, Bernardino de. La historia general de las cosas de Nueva España. 1552. [Nahuatl/Spanish]. Known as the Florentine Codex. The Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain. Trans. Arthur J.O. Anderson and Charles Dibble, 12 books in 13 volumes. Santa Fe: School of American Research, U of New Mexico P, and U of Utah P, 1950.

- The Vertues of Chocolate East-India Drink. Oxford: Henry Hall. 1660.

- Turices, Santiago Valverde. Un Discurso del chocolate. Seville, 1624.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quetzalc%C5%8D%C4%81tl

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kukulkan