Ancient Meso-Americans consumed chocolate in a variety of ways. It could be everything from a ritual potion, to a healing elixir and an everyday beverage.

Originally the taste would be bitter, sweet or alcoholic. Discover how chocolate got a thick, foamy head top and the variety of ingredients used in historical chocolate recipes.

In this Article

The use of stimulants such as cacao and yerba mate, guayusa, guarana, yoco, coca, and tobacco was almost universal throughout the Americas. There is a long tradition of plants being used for alcoholic beverages also, like pulque made from maguey plants and chicha, beer prepared from maize or quinoa . It is very probable that the Mesoamericans were mixing cacao with alcoholic substances.

Cacao – or traces of the compounds theobromine and caffeine – have been found in archaeological deposits from a number of civilizations ranging from the Chaco Canyon in New Mexico to Guatemala.

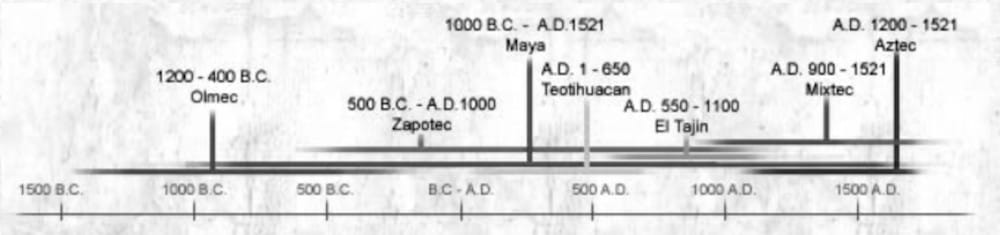

Archaeological evidence on the usage of cacao in the form of a liquid drink points to the Mokaya culture during the “Barra” ceramic phase (c.1900–1700 BC), predating the Olmecs (c. 1200–400 BC), in which their elaborate pottery is hypothesized by scholars to have been used for display of valued drinks, rather than cooking.

Chocolate would be served at Maya (c. 1000BC–900 CE), Toltec (950 to 1150 CE) Aztec (1300–1521) and Inca (c. 1438–1533) social gatherings, festivals and feasts:

“…and from time to time they brought him [Motecuhzoma] some cups of fine gold, with a certain drink made of cacao…I saw that they brought more than 50 great jars of prepared good cacao with its foam, and he drank of that; and that the women served him drink very respectfully…”[sic]

Bernal Díaz del Castillo about the Inca Aztec emperor Moctezuma

Chocolate preparation from bean to brew

Sophie and Michael Coe, in “The true history of Chocolate”, suggest, that the process for chocolate preparation involved four main steps. The cacao seeds must go through:

- fermentation,

- drying,

- roasting (or toasting), and

- winnowing.

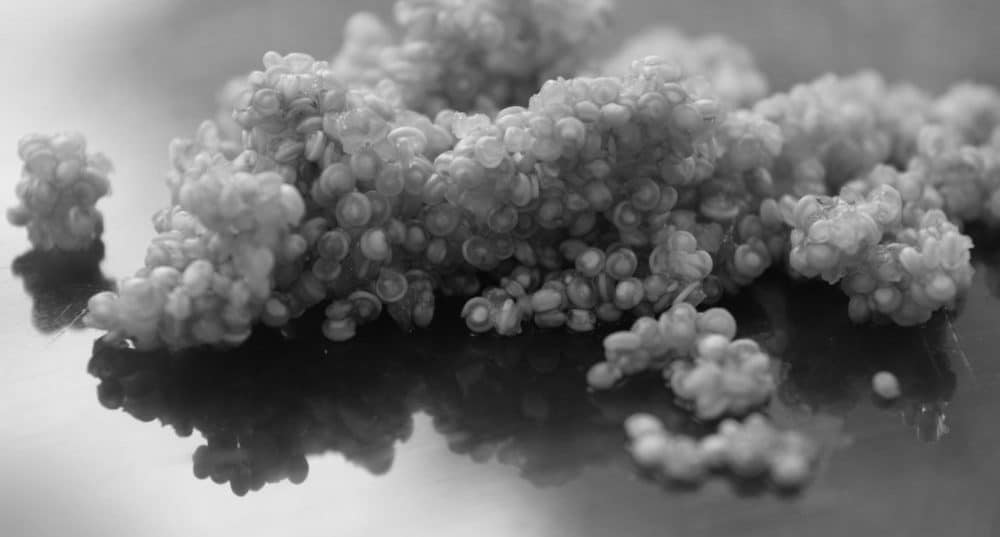

The cacao seeds are first fermented along with the pulp between three and five days (depending on the kind of cacao used either criollo or forastero cultivars).

The cacao seeds are turned occasionally throughout this fermentation period and kept at temperatures between 40°C to 50°C.

The fermentation lowers the astringency of the cacao seeds, so that they are no longer bitter, and gain a pleasurable chocolate taste.

Once the cacao beans are dry after spreading them on mats or trays in the sun for one to two weeks, these lose more than half of their original weight and are consequently roasted at 99°C to 114°C to produce chocolate, or 116°C to 121°C for cocoa powder.

This is a crucial step as it reduces microbiological contaminants and acidity, introduces various flavors, and loosens shells for the subsequent step, the winnowing or de-shelling of the roasted bean.

The resulting product is called a cacao nib, which is then grounded to make a chocolate paste or liquor on a metate.

This curved stone surface on which people from Olmec to Aztec civilizations ground grains like cacao, beans and maize, was a crucial Mesoamerican tool, still being used by some chocolate makers today.

The paste was usually diluted to a drink, which was taken hot or cold, but could also be made into thicker gruels or soups, or even dried to form cakes of chocolate which could then be consumed while traveling.

Nixtamalization of maize (corn) and chocolate

One of the important precursors to chocolate production was the discovery of maize nixtamalization by the Olmec. The amino-acid enhancing properties of the process dramatically increased the nutritional value of maize.

Through nixtamalization, the maize grains were also softened in bulk as they were cooked with lime or ash and left overnight. After the process they could be easily ground into powder on a metate, resulting in a smooth dough (nixtamalli). Nixtamalli mixed in water with the chocolate paste was one of the foundational recipes that persisted in the chocolate production of the Maya and Aztec as saca.

The Aztec saca was a less prestigious drink mainly consumed by the commoners. Elite cacao drinks contained pure cacao, to which were added several subtle – and often highly prized – ground and roasted flavorings and spices.

Nobility, lords, royal house, long-distance merchants, and warriors; but not priests would drink it at the end of the meal, usually while smoking tobacco, during banquets as well as at ordinary meals.

Chocolate preparations would also be served on special occasions like births, feasts, inaugurations, healings, wedding ceremonies and funerary rituals (which sometimes involved the mixing of human blood into the drink).

Thick foam

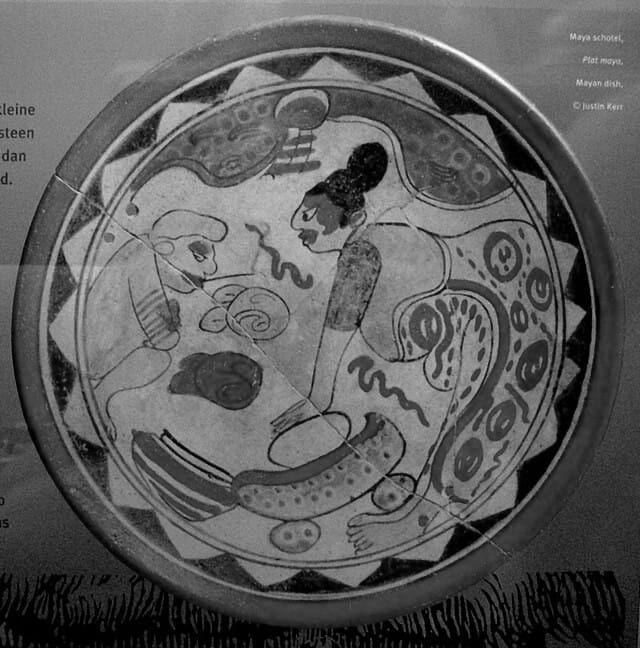

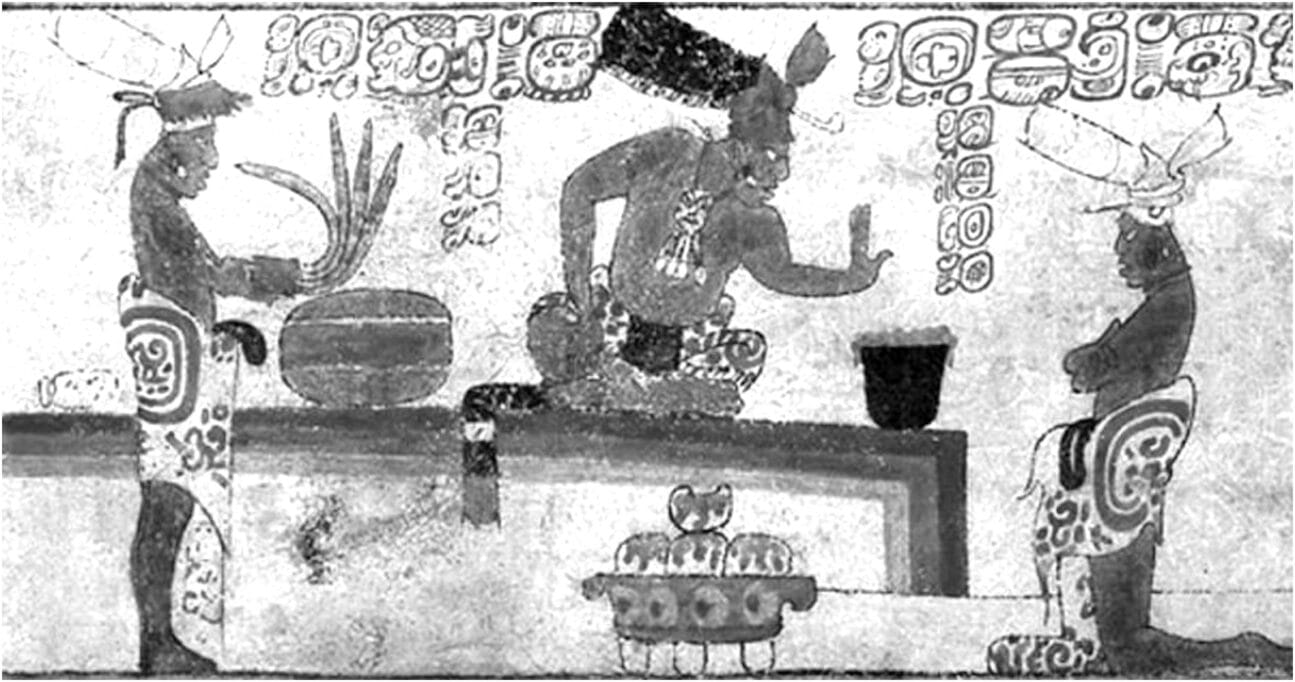

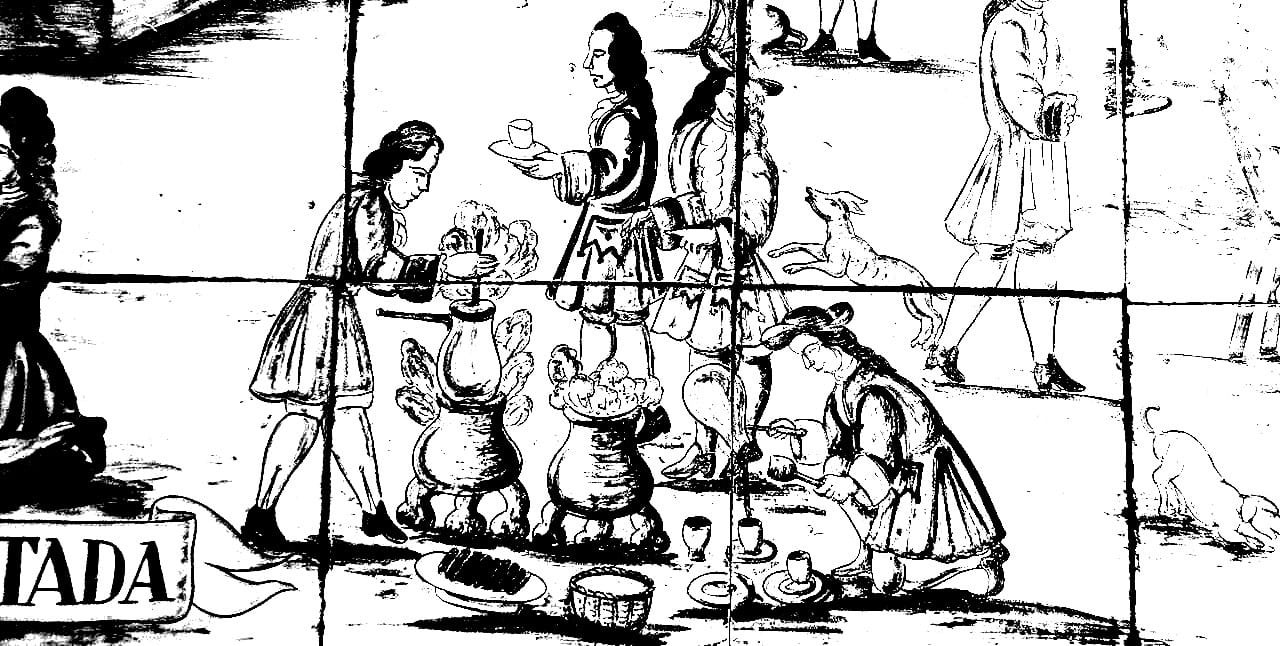

Evidence from the codices and painted chocolate pots, show the method used to create a thick, foamy head to the chocolate, was pouring it from extended heights into another vessel.

Drawing of a detail from the “Princeton Vase” by Diane Griffiths Peck, published in Michael Coe’s The Maya Scribe and His World, edited.

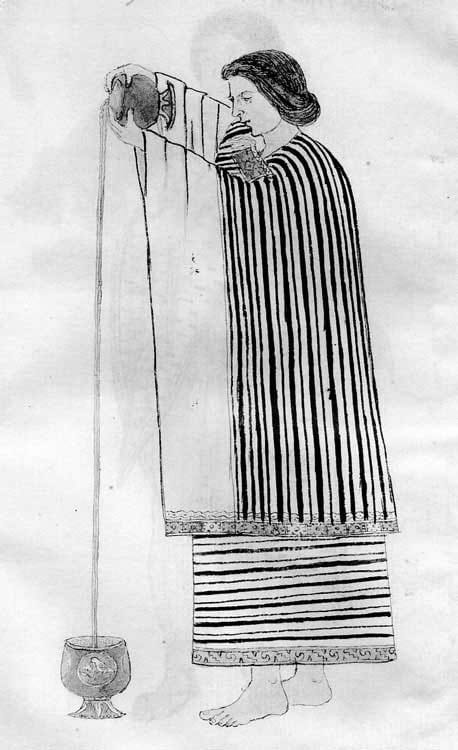

Pouring cacao to froth it; Codex Tudela fol. 3r . Public domain, edited.

The drawing shows an Aztec woman pouring chocolate from above into another vessel from Codex Tudela (left). The same process is also depicted on the Princeton Vase (Maya) dating to eight centuries earlier. This vessel shows a woman pouring chocolate from one cup to another in a palace scene. By pouring chocolate – from a considerable height – from one vase to another the cocoa butter rises to the surface and froth is obtained.

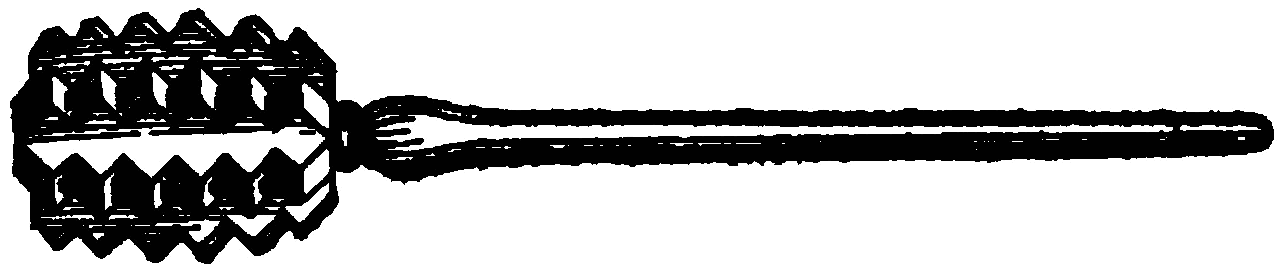

The accounts of Spaniards such as Hernán Cortés, Bernal Díaz del Castillo, Bernardino de Sahagún, among others, discuss the utensils used by the Aztecs to make chocolate, including golden, silver, or wooden spoons to mix the drink and create thick foam. However, there is no mention in the historic records of people using wooden beaters or swizzle sticks (Spanish molinillo).

As suggested by the residue analysis, as well as from iconographic evidence, the elites began frothing the chocolate using the molinillo, only after the arrival of the Spanish, Coe and Coe state.

Public domain, edited.

This French engraving, frontispiece for Dufour’s 1685 work, depicts a fanciful Aztec clad in feathers and holding weapons. On the floor to the left there is a Spanish? porcelain cocoa cup, to the right the long-handled South American chocolate pot, together with the moline or molinillo, used to beat up the froth.

How was chocolate originally consumed by Mesoamerican communities

Mesoamericans were every bit as capable of applying individual taste and invention to the raw materials at hand as the most “creative” of modern chefs.

Scholars of Ethnobotany and Ethno- Anthropology suggest, that the juicy, pleasant zesty fruity flavor and sweet pulp that surrounds the bitter cacao seeds within the pod, are still eaten in the Amazon region – where wild cacao trees grow.

The fermented sugary pulp surrounding the seeds results in an alcoholic cacao beverage that could be consumed ever since. The fresh Cacao fruit pulp is refreshing, and depending where it was grown, it can taste floral, honey, citrus-like or tropical.

Pre-Conquest chocolate derived by the seeds, was not a single concoction to be drunk; it was a vast and complex array of drinks, gruels, porridges, powders, and probably solid substances, to all of which a wide variety of flavorings could be added.

Variations of Cacáo glyphs painted on pottery include a host of cacao drinks (after Coe and Coe):

YUTAL KAKAW (generally translated ‘fruity cacáo’) –

the most common inscription on Classic Maya vessels

SUUTZ KAKAW –

capulin (Prunus serotina) or black cherry

TZAH KAKAW –

sweet cacáo

SA’AL KAKAW –

gruel-ish chocolate (probably corn + cacáo)

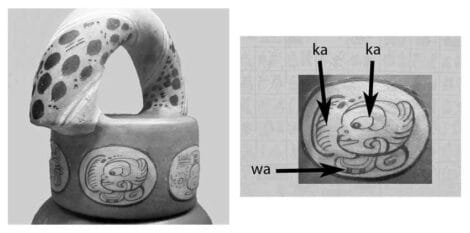

The glyph for Kakau is found an first deciphered on “The Rio Azul chocolate pot” (c. 455 – 465 CE) – the Rosetta stone of cacáo, discovered in Tomb 19 at Rio Azul Guatemala.

This vessels were labor-intensive arts and crafts and among the most important valuables a Mesoamerican owned.

Flavors of Mesoamerican chocolate

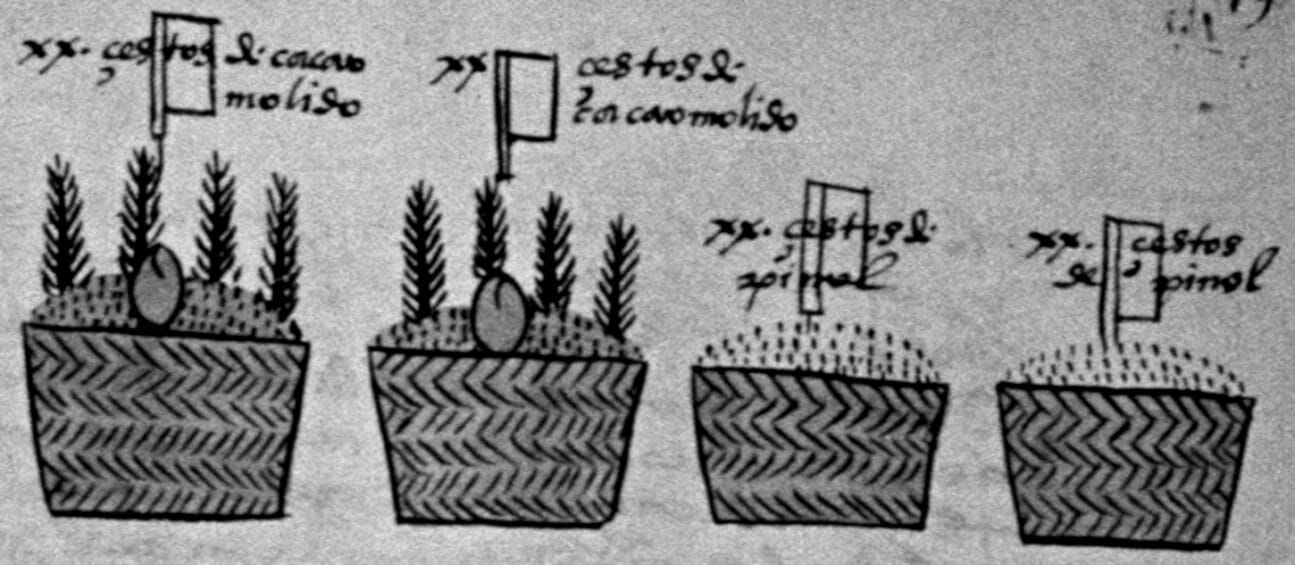

Classical Mayan cocoa drinks were often hot and consisted of gruels (mixed grains in water). This gruel made of maize and cocoa also included ground chilies and other spices. The drink is called pinole today.

Tlahcuiloh (Artist), Florentine Codex. The codex is housed at the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana in Florence, Italy. In 2015, the codex was incorporated into UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register. Public domain, edited.

Because the Mayan empire expanded over nearly 40 cities across the Yucatan Peninsula, recipes varied from region to region as cacao pods and spices grown in each region differed. These variations are highlighted by Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagun in the 1577 Florentine Codex: “And in finishing eating, next was set out many kinds of cacao, ‘cacahuatl‘, made very delicately, like these:

Xoxouhqui cacaocintli , xoxouhqui tlilxochyo[blue-green cacao pod], cacao made with the tender cacao pod, and is very tasty to drink.

Quauhnecvio [mature/great honey] cacao, cacao made with honey from bees.

Xochio [flower] cacao, cacao made with vej nacaztli [aromatic herbs].Chichiltic cacahuatl, [achiote?]cacao made red

Huiztecul cacahuatl, cacao made vermilion-red Xuchipal cacahuatl, cacao made orange

Tliltic cacahuatl, cacao made black

Iztac cacahuatl, cacao made white.

Anderson & Dibble 1953–1982 translation and García Garagarza 2023

Sahagún provides a detailed list of different-coloured chocolate beverages prepared for the Aztec ruler – bright red, orange-red, rose-coloured, black, white…

The red-coloured chocolate was probably produced by adding achiote (Bixa orellana tree), whose seed coats provide an important pigment, annatto or arnatto, still used today as a natural food dye. Achiote was also used ‘to provide sustenance’.

The Scholars Houston and David Stuart are fairly certain that in a few surviving texts, there are references to a chocolate flavoring called there itsim-te. This must have come from the small tree still called by that name, and known scientifically as Clerodendrum ligustrinum; parts of this plant were used by the Colonial period Maya of Yucatán to give a good taste and odor to gruels and sweet potato stews.

Another plant, ‘tall, fine-looking, with a white flower that looks like a dog-rose, and with a rose scent and flavour’ (Coe & Coe), whose scented flowers were used to flavor both chocolate and tobacco was ‘izquixochitl‘ , popcorn flower (Bourreria huanita).

Izquixochitl was specifically mentioned in Sahagún’s Florentine Codex as being important in the preparation of chilled chocolate drinks.

Cocoa was also used as curative, mixed with other plants. Patients with severe cough who expressed much phlegm were advised to drink infusions prepared from opossum tails first. Then a second medicinal beverage was served, where chocolate was mixed with three herbs:

- Mecaxochitl

- Piper sanctum, a relative of black pepper

- Tilixochitl

- Vanilla planifolia, which is vanilla, and

- Hueinacaztli or Uey nacaztli

- Chiranthodendron pentadactylon, which tastes spicy like black pepper.

Syrup of maguey (Agave) and bee honey would be used as sweeteners.

Chocolate ingredients native to the Americas:

Mesoamerican communities prepared multiple drinks involving chocolate along with other condiments such as: chilly, ceiba seed( Silk-cotton tree seeds), hueinacaztli (Great ear type of flower), Magnolia Mexicana, achiote (orange-red spice and coloring agent extracted from the seeds of the Bixa orellana shrub), and pimienta (black pepper).

| Achote (Bixa orellana ) | Allspice (Pimienta dioica ) |

| Chichiualxochitl (breast flower?) | Chili pepper (many varieties) |

| Eloxochiquauitl (?) | Gie’ cacai (flower?) |

| Gie’ suba (flower?) | Hueinacazztli (Cymbopetalum penduliflorum ) |

| Izquixochitl (Bourreria spp.) | Maize (Zea mais ) |

| Marigold (Tagetes lucida ) | Mexacochitl (string flower) |

| Piñon nuts (Pinus edulis ) | Piztle (Calorcarpum mammosum ) |

| Pochoctl (Ceiba spp.) | Quauhpatlachtli |

| Tlilxochitl (flower of Vanilla planifolia ) | Tlilxochitl (pod/beans of Vanilla planifolia) |

| Xochinacaztli (Cymbopetalum penduliflorum ) | Yolloxochitl (Magnolia mexicana) |

| Zapayal (Calorcarpum mammosum) | Zapote (Achradelpha mammosa) |

On the eve of the Spanish Conquest, chilli pepper was very popular as a chocolate flavoring among the Aztecs, as well, – since it imparts a very pleasurable “burn” to the drink.

According to indigenous traditions from Mesoamerica, chocolate fits a variety of uses. It could be everything from a ritual beverage to a healing elixir to an everyday drink.

Fabulous references to Cacao benefits and preparation from early Colonial Mexico

The discussions of cacao by representatives of the Catholic Church in Mexico record its appealing flavor and qualities:

Motolinia (1971, Chapter 8:218–219) wrote that cacao: “when ground and mixed with corn and other seeds, which are also ground . . . serves well as a beverage and is consumed in this form. . . It is good and they consider it a nutritious beverage.”

Sahagún (1950–82, Book 11, 1975:119–120) stated: “This cacao, when much is drunk, when much is consumed, especially that which is green, which is tender, makes one drunk, takes effect on one, makes one dizzy, confuses one, makes one sick, deranges one. When an ordinary amount is drunk, it gladdens one, refreshes one, consoles one, invigorates one. Thus it is said: I take cacao. I wet my lips. I refresh myself.”

Also, Bartolomé de las Casas (1909:552) expresses: “The drink (chocolate) is water mixed with a certain flour made of some nuts called cacao. It is very substantial, very cooling, tasty, and agreeable, and does not intoxicate.”

By the end of the seventeenth century, chocolate was popular across the Atlantic, particularly in the Europe’s capitals and Atlantic port cities. However, in spite of its wide-spread use at the everyday level, its consumption was the subject of confusion and consternation by skeptical physicians and the first coffeehouse guests.

Colmenero de Ledesma

Colmnero de Ledesma noted that many Europeans of the era debated its qualities and application. In his 1631 account titled Curioso tratado de naturaleza y calidad del chocolate, represented the first full-length printed account dedicated to chocolate. The surgeon celebrated the beverage and confectionery for its healthy and healing qualities, but not only that.

“My desire,” he noted in the opening of the work, “is for the benefit and pleasure of the public, to describe the variety of uses and mixtures so that each may choose what suits their ailments.”

When produced with the right art and process, Colmenero de Ledesma suggested that his recipe for chocolate could be remedial, protective, and healthy. “Through my experience in the Indes” he declared,

“when visiting a sick person in the heat, I was persuaded to take a draft of chocolate, which quenched my thirst. And, in the morning, if I had fasted, it warmed and comforted my stomach.”

Colmenero de Ledesma’s recipe for chocolate

For the preparation of the chocolate beverage, Colmenero de Ledesma suggested that the ingredients be ground on a metate, explicitly reserved for grinding cacao. All ingredients, save the achiote, were to be dried and ground individually into a powder.

To every one hundred Cacao beans, mix two large chiles of the type that are called Cilparlagua in the Indies (or you may use the broadest and least spicy chili found in Spain). Add in one handful of anise seeds along with the leaves of the herb called Vincaxtlidos and the other called Mecasuchil [mecaxóchitl], if the stomach is tight.

Or, as we do in Spain, mix in the six flowers of the Roses of Alexandria, which are beat into a power. Add one pod of the Vanilla of Campeche, two sticks of cinnamon, a dozen almonds and hazelnuts, and a pound and half of sugar. Add in enough achiote to give it color.

Begin, he directed, by grinding the cinnamon, then the chili with the anise, then moving to the others. Next carefully mix each pulverized ingredient into the cacao a little at a time. Finally, add the achiote. Over a low fire, the pulverized mixture is to be seared and dried into a paste, which was to be spooned onto paper or a plantain leaf. The cooled paste would form a tablet that could subsequently be dissolved with water and sugar.

Consumed cold or warm, Colmenero de Ledesma’s recipe for chocolate would invariably have something novel to the seventeenth century palates on both sides of the Atlantic. He stated:

“no small matter, to have pleased all.”

In the Americas, chocolate was traditionally consumed as a frothy, spicy beverage, free of the sweetness of modern cocoa. Colmenero de Ledesma’s recipe, however, combined herbs and spices of the New World. It is noteworthy that the surgeon hispanized indigenous terms, including cilparlagua and mecasuchil. Moreover, the addition of sugar fundamentally redefined the experience of the beverage.

Rather than taking on the earthy and bitter qualities of the cacao, the sugar would have lent an overwhelming sweetness to the beverage.

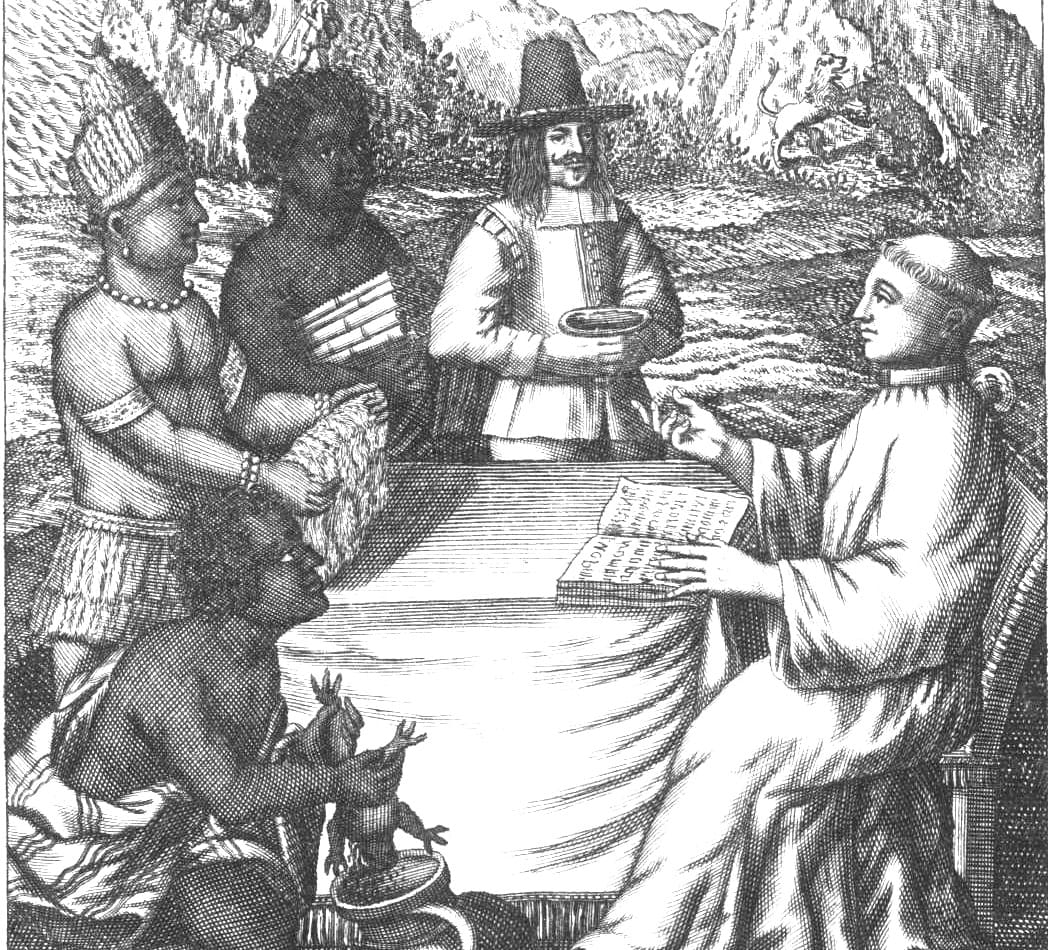

Within a decade, Colmenero de Ledesma’s curious treatment of chocolate would be translated and published in England, France, Germany, and Italy. The front piece to Antonio Colmenero de Ledesma’s, Chocolata Inda, Opusculum de qualitate & naturâ de Chocolatæ (Nüremberg, 1644), shows the Indies, personified as a maiden, giving the gift of chocolate to the Atlantic world, personified as Poseidon.

Chocolata inda : Opusculum de qualitate & naturâ chocolatae, (1644). Public domain, edited.

Thomas Gage

In A New Survey of the West-Indies of 1655, the English friar Thomas Gage celebrated the qualities of chocolate:

“Chocolate,” wrote the Dominican priest, was consumed in “all the West-India’s, but also in Spain, Italy, and Flanders, with approbation of many learned Doctors in Physick.” [sic]

He described chocolate as: “unctuous, warm [with] moist parts mingled with the earthly” all the while defining it as “one of the necessariest commodities in the Indias.”

Seemingly everyone in seventeenth-century Mexico and Guatemala imbibed in the frothy and sweetened beverage. According to the friar,

Indians produced it, women demanded it, Spaniards celebrated it, and doctors healed with it.

Thomas Gage’s recipe for “chocolatical confection” (chocolate)

The recipe for the Mesoamerican “chocolatical confection” was a rich mixture of indigenous and European herbs and spices:

Put into it black pepper which is not well approved of by the physicians because it is so hot and dry, but only for one who hath a cold liver, but commonly instead of this pepper, they put into it a long red pepper called chile which, though it be hot in the mouth, yet is cool and moist in operation. It is further compounded with white Sugar, Cinnamon, Clove, Anise seed, Almonds, Hazelnuts, Orejuela [anona], Vanilla, Sapoyall [mamey], Orange flower water, some Muske, and as much of these may be applied to such a quanitie of Cacao, the several dispositions of Achiotte, as it will make it look the colour of a red brick.

To prepare properly, he noted that the ingredients must be dried and ground with an Indian metate. The cinnamon and chiles were to be first beaten with warm water and powdered cacao. Subsequently the anise and other herbs and spices were to be individually added to the confection before being “searced” or sifted to remove the shells and hulls. Finally, powdered achiote was to be added to enrich the beverage with a hearty color and earthen flavor.[sic]

The frontpiece to Thomas Gage, Neue merckwürdige Reise-Beschreibung nach Neu Spanien. A New Survey of the West-Indias, second edition (1655) shows the idealized representations of the ranks of the local population, including a Spaniard, African, native, and a mixed ethnic man. The Spanaird presents a bowl of chocolate, while the others offer reeds, cloth, and poisoned toads.

“For myself,” Thomas Gage wrote,

“I must say that used it twelve years constantly, drinking one cup in the morning, another yet before dinner between nine or ten of the clock, another within an hour or after dinner, and another between four or five in the afternoon.”

This four to five cup-a-day, twelve-year regimen of chocolate kept him “healthy, without any obstructions or oppilations, not knowing either ague or fever.”

Anonymous commonplace book recipe from the 18th century for chocolate almonds

To make Chocolate Almonds. Take your Sugar and beat it and Serch [sift] it then: great youre Chocolatt: take to 1 lb Sugar: 5 oz. Of Chocolatt mix well together put in 2 Spoonful Gundragon Soaked in rosewater and a grm musk and amber grease and beat all well together in mortar. Rowl out and markwt: ye molds and lay on tin plates to dry turn everyday. [sic]

Ellis Veryard, declared in his 1701 account of a visit to Spain, “The Spaniards [are] the only People in Europe to have the Reputation of making Chocolate to perfection”.

France and Italy followed Spain and Portugal in adopting the chocolate drink. Chocolate was very popular at the French court, loved by the kings and queens, especially Louis XIV. Alphonse-Louis du Plessis de Richelieu, the Cardinal’s brother, argued that chocolate was useful to

“moderate the vapours of the spleen”.

Alphonse-Louis du Plessis de Richelieu assured people that he knew it worked,because he had tried it himself. Richelieu was convinced that if someone wanted to overcome feelings of anger and bad temper, the answer was to just drink some chocolate. ( Levin Carole.)

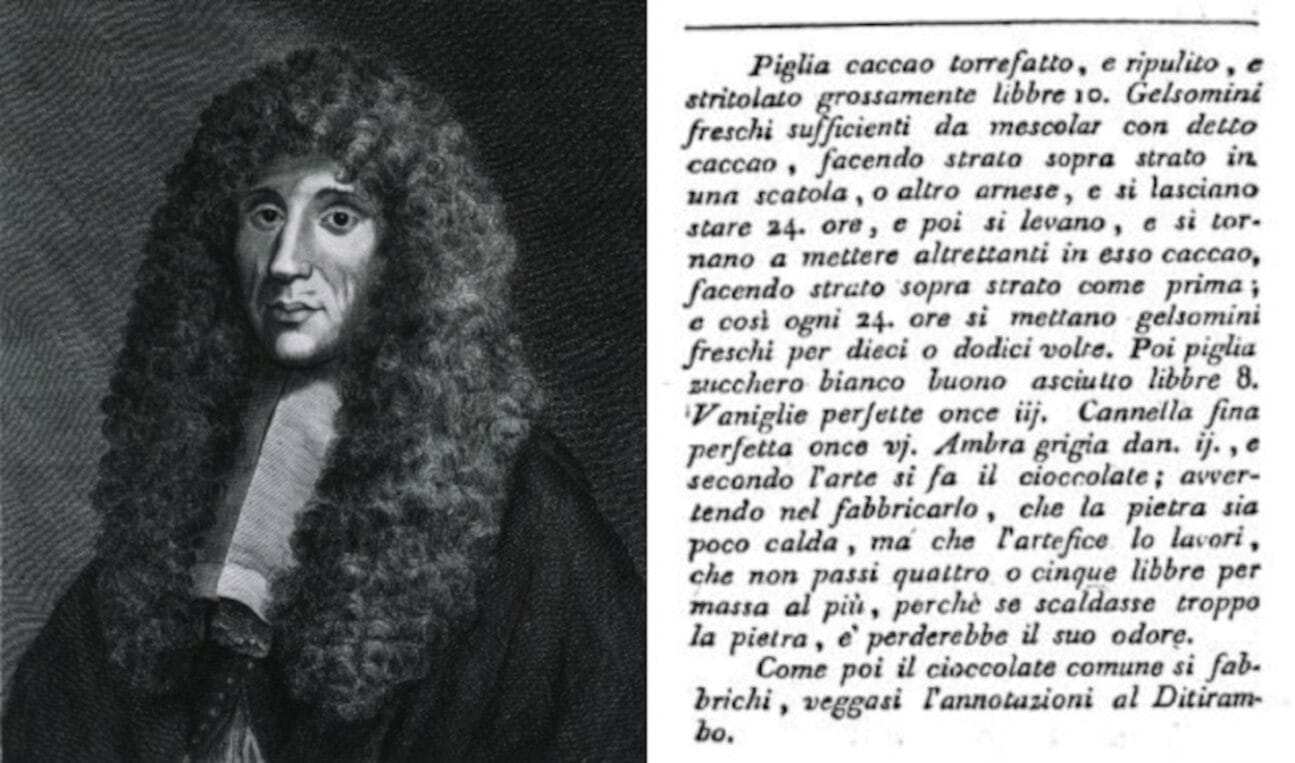

Francesco Redis secret jasmine chocolate for Cosimo III de’ Medici

In the seventeenth century in Italy, perfume-laden flavors were introduced into chocolate. Jasmine chocolate was a specialty at the court of Cosimo III, Grand Duke of Tuscany. He and wife Marguerite Louise d’Orleans loved to drink flavored chocolate. Other Tuscan ingredients added included musk, ambergris, citron, and lemon peel.

Francesco Redi, a scientist, poet, physician and apothecary to Cosimo created the jasmine chocolate drink for Cosimo III de’ Medici (1642-1723), the Grand Duke of Tuscany .

Enfleurage

To make the jasmine chocolate drink was an operation of botanical-gastronomical engineering. The classic enfleurage method of capturing scent with odorless fat, straining and replacing the flowers in the fat till the perfect strength of enfleurage pomade is attained.

Layers of fresh jasmine flowers and chocolate were put one over the other. The process had to be repeated every 24 hours for 12 days. In this way, the jasmine petals provided the cocoa dough with a flavor never tasted before.

This is the classic enfleurage method of capturing scent with odorless fat, straining and replacing the flowers in the fat till the perfect strength of enfleurage pomade is attained.

Jasmine Chocolate of The Grand Duke of Tuscany

Ingredients

10lb [4.5kg] toasted cacao beans, cleaned and coarsely crushed

Fresh jasmine flowers

8lb [3.6kg] white sugar, well-dried

3oz [85g] “perfect” vanilla beans

4 to 6 oz [115 to 170g] “perfect” cinnamon

2 scruples [1/12 oz, 2.5g] ambergris

Method

In a box or similar utesil, alternate layers of jasmine with layers of the crushed cacao, and let it sit for 24 hours. Then mix these up, and add more alternating layers of flowers and cacao, followed by the same treatment.

This must be done ten or twelve times, so as to permeate the cacao with the odor of the jasmine. Next, take the remaining ingredients and add them to the mixed cacao and jasmine, and grind them together on a slightly warm metate; if the metate be too hot, the odor might be lost.

(Recipe from Coe & Coe, 2013, p146)

Modica chocolate

Redi kept the recipe secret, it was only published after his death. In his notes, he describes an interesting process involving grinding the cocoa on a stone (the Aztec metate) that could only be reproduced in Modica, where chocolate is still prepared at low temperature following the original technique brought by the Spaniards in the 16th century.

List of chocolate drink preparations

| Beverage Name | Ingredients |

|---|---|

| French Chocolate | Vanilla, sugar, nibs |

| Spanish Chocolate | Curacoa [sic], sugar, cinnamon, cloves, sometimes almonds |

| Vanilla Chocolate | Caracas, Mexican vanilla, cinnamon and cloves |

| Cocoa Nibs | Bruised roasted seeds deprived of their covering |

| Flake Cocoa | Whole seed nib and husk ground up together until a flake – like appearance |

| Rock Cocoa | Same as Flake, but with arrowroot and sugar |

| Homeopathic Cocoa | Same as Rock Cocoa, but without sugar |

| Maravilla Cocoa | Contains sugar and sago flour |

| Cocoa Essence, Cocoa Extract and Cocoatina | Consists of pure cocoa deprived of 60 – 70 percent of its fat |

| Pressed Cocoa | Cocoa nibs, with only 30 percent cocoa fat |

| Vi – Cocoa | Preparation in which an extract of kola nut is said to be added |

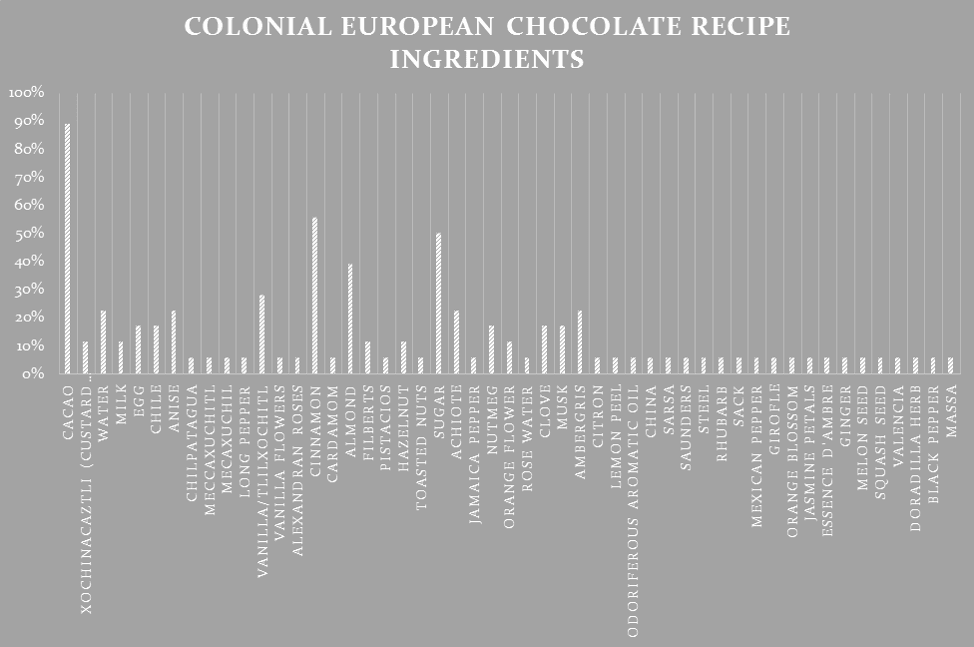

The addition of novel ingredients in European recipes introduced new floral scents, like rose water, orange blossoms, and jasmine. Also the use of nuts was increased, adding almonds, pistachios, and hazelnuts to the drink.

Note: If you do wish to experiment the recipes, we suggest doing further research.

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

Mexicolore is a delightful read, explore if you like.

- Edwards. W. N. The Beverages We Drink. London: Ideal Publishing Union Ltd., 1898

- Hall. Grant D., et al. “Cacao Residues in Ancient Maya Vessels from Rio Azul, Guatemala.” American Antiquity, vol. 55, no. 1, 1990. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/281499. Accessed 12 Mar. 2020.

- https://www.maya-ethnobotany.org/images-mayan-ethnobotanicals-medicinal-plants-tropical-agriculture-flower-spice-flavoring/cacao-flavoring-esquisuchil-bourreria-huanita-popcorn-flower-planted-by-hermano-pedro.php

- Kashanipour R.A. The Curing Chocolate of Antonio Colmenero de Ledesma of 1631.

- https://recipes.hypotheses.org/category/chocolate

- https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/maya/chocolate/history-and-uses-of-cacao

- Pre-Columbian Cacao: The Great Societal Stabilizer

- Dillinger Teresa L., Barriga Patricia, Escárcega Sylvia, Jimenez Martha, Lowe Salazar Diana and Grivetti Louis E. Chocolate: Modern Science Investigates an Ancient Medicine. Food of the Gods: Cure for Humanity? A Cultural History of the Medicinal and Ritual Use of Chocolate. American Society for Nutritional Sciences. 2000.

- Coe Michael D. Coe Sophie Dobzhansky. The true history of chocolate.

- Colmenero de Ledesma. Curioso Tratado de la naturaleza y calidad del chocolate. Madrid, 1631. (Latin 1644)

- Fao infographik http://www.fao.org/resources/infographics/infographics-details/en/c/277756/

- Grivetti Louis Evan. Mesoamerica: cultural history of cacao. From Bean to Beverage. Historical Chocolate Recipes .

- Grivetti Louis Evan & Shapiro Howard-Yana. Chocolate: History, Culture and Heritage. 2009.

- https://recipes.hypotheses.org/date/2021/04

- https://recipes.hypotheses.org/17881

- https://recipes.hypotheses.org/5454