Read about sacred Rituals done by Taoist priests and spirit mediums, caught in meditative trance, during the festival. It starts with the welcoming of the gods into the temple where they are worshiped for nine days, and ends when the gods are sent off on the ninth day.

The festival is known for the temple processions that take place during the celebrations. Discover Myths and Folklore of the Nine Emperor Gods Festival in Georgetown – Penang.

In this Article

The Nine Emperor Gods Festival or ‘Kew Ong Yeah’ Festival in Hokkien is held from the first to the ninth day of the ninth lunar month [usually around September-October] among Chinese communities in Southeast Asia, including in Malaysia (called Hari Sembilan Maharaja Dewa) , Singapore, and Thailand (called เทศกาลกินเจ). The festival is dedicated to the nine sons of Tou Mu, the Goddess of the North Star believed to control the Books of Life and Death.

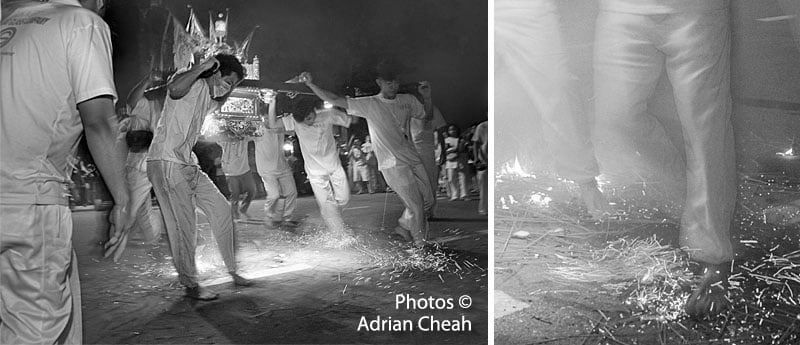

For nine days, devotees offer prayers and practice a vegetarian diet. Some display their dedication with extreme acts that is not for the faint-hearted. These include walking on hot coals, seating on nailed chairs, rolling a heated iron ball through the streets, and ritualized self-mutilation such as skewering the cheeks with a spear while in a trance.

The three most prominent Nine Emperor Gods temples in Penang are: Macallum Street’s Tow Boo Kong Temple, Burma Road’s Tao Bo Kong Temple, and Tow Boo Kong Temple Butterworth. At the nine days festival more temples and over 50 spirit mediums participate.

Kew Ong Yeah – The Nine Emperor Gods

There are multiple accounts of who the Nine Emperor Gods, 九皇爺, also known as Jiu Huang Ye, Kow Wong Yeh, or Kew Ong Yah, are and what their worship represents.

MYTH: Tou Mu – The Goddess of the North Star

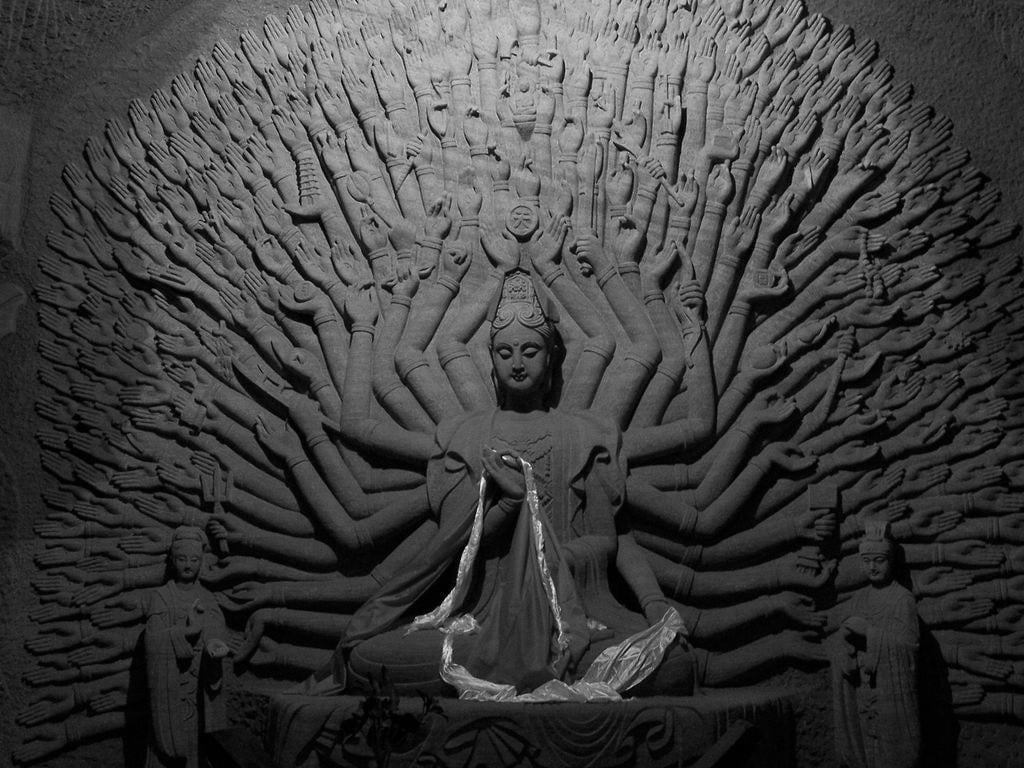

Tou Mu or Dou Mu, Dou Mu Yuan Jun (斗母元君) , the Bushel Mother, or Goddess of the North Star, worshiped by both Buddhists and Taoists, is the Indian Maritchi, and was made a stellar divinity by the Taoists.

She is said to have been the mother of the nine Jên Huang or Human Sovereigns of fabulous antiquity, who succeeded the lines of Celestial and Terrestrial Sovereigns. She occupies in the Taoist religion the same relative position as Kuan Yin – the mother of mercy, who may be said to be the heart of Buddhism.

Having attained to a profound knowledge of celestial mysteries, she shone with heavenly light, could cross the seas, and pass from the sun to the moon. She also had a kind heart for the sufferings of humanity.

The King of Chou Yü, in the north, married her on hearing of her many virtues. They had nine sons. Yüan-shih T’ien-tsun came to earth to invite her, her husband, and nine sons to enjoy the delights of Heaven. He placed her in the palace Tou Shu, the Pivot of the Pole, because all the other stars revolve round it, and gave her the title of Queen of the Doctrine of Primitive Heaven.

Her nine sons have their palaces in the neighboring stars.

The Nine Emperors is formed by the seven stars of the Big Dipper of the North Ursa Major (visible) and two assistant stars (invisible to most people).

The Nine Emperor Stars are:

1st Star (Visible) Bayer: α UMa Tan Lang Tai Xing Jun 貪狼太星君

2nd Star (Visible) Bayer: β UMa Ju Men Yuan Xing Jun 巨門元星君

3rd Star (Visible) Bayer: γ UMa Lu Cun Zhen Xing Jun 祿存貞星君

4th Star (Visible) Bayer: δ UMa Wen Qu Niu Xing Jun 文曲紐星君

5th Star (Visible) Bayer: ε UMa Lian Zhen Gang Xing Jun 玉廉貞綱星君

6th Star (Visible) Bayer: ζ UMa Wu Qu Ji Xing Jun 武曲紀星君

7th Star (Visible) Bayer: η UMa Po Jun Guan Xing Jun 破軍關星君

8th Star (Invisible) Zuo Fu Da Dao Xing Jun 左輔大道星君

9th Star (Invisible) You Bi Da Dao Xing Jun 右弼大道星君

Jiu Ren Huang Version

The earliest account is that of the Jiu Ren Huang, according to which the Nine Emperor Gods were reincarnates of the Nine Human Sovereigns, who were in turn the sons of the goddess Dou Mu. After gaining enlightenment, Dou Mu imparted her transcendental knowledge to her nine sons.

Her sons became the star deities known as beidoujiuxing, which are known in the Western constellations as the Northern Dipper. Dou Mu, as the mother of the Northern Dipper, is also known as the Dou Mu Tianzun (Heaven-honoured Bushel Mother). Together with her husband, she controls the pivot of the North Pole, around which the nine stars revolve under the surveillance of her sons.

According to the Taoist belief, the Northern Dipper controls the fate of individuals and the welfare of the state.

In addition, the northern direction is associated with the water element – the symbol of life and death – and Dou Mu is known as a merciful water spirit who offers protection for seafarers.

However; some believe that the nine divinities were adopted sons or disciples.

The Penang Version

The Penang version suggests that the Festival of the Nine Emperor Gods is held in remembrance of the nine brothers associated with the last prince of the Ming dynasty. These brothers, from a fishing village in Fujian Province, are said to have helped the prince escape by forming a squad that escorted him from Fujian to Songkhla, Thailand, via Yunnan.

They arrived in Songkhla under the guidance of the nine northern stars; after their arrival the stars gradually disappeared, and so did the prince and the nine divine brothers.

Shortly afterwards, the story goes, nine censers were found floating on the sea near Songkhla (some accounts mention instead Phuket Island, off the west coast of southern Thailand). The censers were believed to be the manifestations of the nine divine brothers, who had since ascended to the southern heavens. Their spirits, however, continue to visit the Chinese community during their yearly tour of the South Seas.

Censers, regarded as the vehicles of the Nine Emperor Gods, are still used in the welcoming and sending – off ceremonies of the festival.

Hong Secret Society – Ampang Version

~ Cheu Hock Tong at the National University in Singapore retells this version of the myth:

It relates the connection of the Hong Secret Society (hongmenhui 洪門會 or hong banghui 洪 會 ) in Penang to the Festival of the Nine Emperor Gods. According to this account, a Hong member by the name of Wan Yunlong was killed in a battle with the Qing forces at Changsha, Hunan, on the ninth day of the ninth month 1783.

His followers fled to Thailand, where, rebuffed by the Thai authorities, they moved south to the Penang area in present-day Malaysia. Some Hong members settled in Ampang, where they worked as planters and farmers and organized a clandestine movement to overthrow the Qing and restore the Ming.

Once when this group was performing an initiation ritual for new recruits the police came to investigate. When they inquired about the purpose of the gathering, the group replied that it was praying for peace and protection. Seeing that there was only an incense urn and no image of any sort, the police said, “There’s no deity here — what are you worshipping ?, hereupon one quick-witted soul pointed at the incense urn and replied,

“This is the god [shen 神] we worship!”

Amused by the answer, the police asked, “If this incense urn is your god, then what is it called?” Another member replied, “It is called Jiuhuang Dadi 九皇大帝.” The police took their word for it and departed. This accounts for the use of an incense urn to represent the Nine Emperor Gods during the festival.

Changing legends

Over time, new versions of Nine Emperors emerge associating them with new identities and the origins. They were said to be 9 emperors of ancient China, 9 martyrs of the Qin dynasty, underground Ming loyalist leaders and even Zheng Cheng Gong, Koxinga, the famous Ming loyalist who captured Taiwan from the Dutch.

Nine Emperor’s association with the Ming loyalists is said to be due to the sculpture of Dou Mu, mother of the Nine Emperors. She is seen with arms stretched and holding on to a sun and moon. When the Duo Mu sculpture is seen against a mirror, the Chinese character of the sun, 日, and moon, 月, form to become the character, bright or Ming, 明, the same character as the Ming dynasty, 明朝.

The Nine Emperor celebrations has since acquired associations with the movement to restore the Ming dynasty.

The Han Version

Another version dates back to the end of the Han dynasty, when the Taoist magician Zhang Daoling (Zhang Tianshi) used charms and talismans to cure the afflicted. Those consulting him were required to pay five pecks of rice, because of which his cult was nicknamed Wudoumi Dao 五斗米道 (the way of the five pecks of rice).

Some accounts claim that he used magic to spread epidemics, causing people to turn to him for treatment. By so doing he became wealthy and powerful, so much so that he no longer bothered to pay taxes to the royal court. Aware of his actions, the emperor summoned him to the palace to teach him a lesson. In preparation the emperor ordered nine scholar-musicians into a secret compartment and told them to start playing eerie music as soon as a secret switch was thrown. When Zhang Daoling was before him the emperor threw the switch, then asked Zhang to exorcise the “spirits” that were causing unrest in the palace. The emperor was certain that Zhang would fail and thus be humiliated.

His plan backfired, however. Upon being challenged to exorcise the demons, Zhang calmly looked around the palace. He then unfolded his magic fan, which immediately revealed the whereabouts of the musicians.

He scattered some rice and salt on the floor, then made a chop with his magic sword. All nine scholars in the secret compartment were beheaded and the eerie music came to a halt.

Because of his fear that the nine scholar-musicians would haunt the palace, the emperor ordered the severed heads to be interred in a large earthenware vase. The vase was sealed, labeled with a talisman paper to prevent the spirits from escaping, then thrown into the sea. Shortly afterwards, however, the emperor was disturbed night after night by dreams in which the bloody apparitions of the nine musicians appeared, asking him to canonize them as the “Nine Emperor Gods.”

The emperor was too frightened to refuse.

This version, has served as a model for many of the oral myths circulating among devotees. The main difference is that one version ends at the nine scholars, canonization by the emperor, while many of the oral versions recount the adventures of the nine severed heads in the earthenware vase and their final ascent to heaven.

Some emphasize the white blood that oozed from the heads, thus accounting for devotees’ wearing of white headgear during the festival.

Nan Tian Gong Version

The Nan Tian Gong account is one that takes the Han version a bit further, relating that some fishermen found a vase floating in the sea off Kongka (Songkhla). Strange voices came from it, calling for help. As the fishermen’s boat approached the vase a voice beseeched them to remove the talisman paper and unseal the vase. They did as they were told, and saw nine heads soaring into the sky in broad daylight!

Later one of the fishermen had a dream in which the nine divine brothers warned him of an impending storm, but assured him that he would be safe if he erected a flag on the masthead with “Jiuhuangye” (Nine Emperor Gods) written on it. The fisherman followed the instruction, but the other crews just laughed at him when he advised them to do the same. Sure enough, the next time they set sail there was an unusually fierce storm, and all the boats except the one bearing the flag were wrecked and their crews drowned.

In Hong Kong street, Penang a pole with flag is erected every year at the same sacred place, for the Nine Emperor Gods festival. Bamboo poles with flags are seen all over Penang.

Origin of the belief in Malaysia and Singapore

Worship of the Nine Emperor Gods is said to have originated in Fujian, China, where many folks in Penang trace their ancestral roots. Apparently, a youth from China, Lin Yin, brought scrolls of the Nine Emperor Gods to Penang. The scrolls now lie in the temple of the Nine Emperor Gods in the town of Ampang in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

In another account, tin miners in Kuala Lumpur during the early 19th century began succumbing to a deadly illness. It was said that Ong Choo Kee, this time a physician, happened to be in sole possession of an original sacred text from China belonging to the Nine Emperor Gods. He visited the miners and, whilst there, became possessed by the spirits of the gods. The deities spoke through Ong and drove away the evil spirit responsible for the miners’ illness. Ong then came to Singapore and set up a small temple along Upper Serangoon Road dedicated to the Nine Emperor Gods. Two rich men, Ong Chwee Tow and Ong Koi Gim, later donated large sums of money to the temple, and a new one was built on the site. The structure, which still stands today, was gazetted as a national monument in 2005.

De Bernardi J.E. tells, in her book, Penang: Rites of Belonging in a Malaysian Chinese Community:

According to the president of Penang’s oldest Nine Emperor Gods temple, their fist temple was a simple shelter built in the 1840 on Beach Street, at which time they also acquired from China the gods’ scripture and a sacred tablet.

But others claim that a Thai trader brought the cult to Penang in the 1880 from Phuket, an island off the southern coast of Thailand.

According to one temple caretaker, Penang experienced an epidemic in which hundreds died, and a visiting Thai trader advised the Chinese to worship the Nine Emperor Gods (Kiuhong Taite, liuhuang Dadi). Once people began to worship them, the epidemic stopped.

Meanwhile, five monks are said to have built the Temple of Clear View (Cheng Koan Si, Qingguan Si) in 1880 on Paya Terubong Hill facing the sea. During the festival many climb 1,002 hewn granite steps (chhengji Chan, qianer ceng) to this temple, nestled in a valley just below the hill’s peak, following the widespread Chinese tradition of ascending to the heights (denggao) 0n the ninth day of the ninth lunar month. Even the Qing court observed this tradition: on the double-nine day, the emperor, empress, and imperial concubines scended to a pavilion 0n the peak of a miniature stone mountain built within the walls of the Forbidden City, a hill with a cave at its

heart that the Qianlong emperor inscribed with the characters yungen, “root of clouds.”

Nineteenth-century sources suggest that many of the ritual practices now associated with worship of the Nine Emperor Gods in Penang probably were not adopted until the 1880. James Low described a ceremony on the ninth day of the ninth lunar month in which Chinese “drove away disease and pestilence” by flying paper kites”. he does not mention any Nine emperor gods celebration.

According to some accounts, a businessman by the name of Ong Choo Kee was in Penang to make a business deal, and made a vow to worship the Nine Emperor Gods for the rest of his life in exchange for a successful deal. He subsequently returned to Singapore, bringing with him either the statue of one of the gods or an amulet representing all nine, and installed it in a small temple near his home. He later built a temple dedicated to the Nine Emperor Gods along Upper Serangoon Road, which is known today as the Hougang Tou Mu Temple.

Nine Emperor Gods Festival Celebration in Penang

Devotees believe that the Nine Emperor Gods bestow wealth and longevity on their worshipers. Rituals held during the festival differ among temples in different countries.

Vegetarian ritual and raising of the jiuqudeng

The festival begins on the last day of the eighth lunar month with the raising of the jiuqudeng, which refers to an oil lamp with nine wicks.

This is when the spirit of the Nine Emperor Gods who are believed to dwell in the stars manifest in the mortal world and possess the spirit mediums, putting them under a spell. Many of these mediums can be seen in action, caught in meditative trance, during the festival.

The lamp is raised to invite divinities to the temple grounds in celebration of the festival. It has to stay lighted throughout the nine days as it is a sign of continuous divine presence. The vegetarian ritual starts on the same day, when Jiu Huang Ye followers are expected to abstain from meat and sex in order to purify their bodies.

Welcome ritual

The welcome ritual is typically held the following day, which is also the first day of the ninth lunar month. A street procession starting from the temple proceeds to a nearby sea where the gods are to be invited.

The procession consists of lion and dragon dance troupes and devotees following behind sedan chairs carrying statues of accompanying gods as well as the sacred urn. Bearers of the sedan chairs, who are dressed in white, sway the chairs forcefully to symbolize the presence of divine forces.

A spirit medium who may accompany the procession points out places where supposed evil spirits lurk. A Taoist priest or medium will then purify the indicated spots.

Firecrackers and beating drums go on for days, and Lion dances and dragon dance performances are seen.

Lion Dance

舞狮子 wǔ shī zǐ, Lion dance is an ancient art form brought from China by early Chinese immigrants, and over time has evolved into a distinctive Malaysian style.

Lion dances are performed by two “dancers” in a lion costume, rather like a pantomime horse. The performers become the body of the lion: the one in front is the head and front limbs, the one behind is the back and hind legs. Performers’ legs are dressed the same color as the lion’s body, and sometimes the costume extends to shoes the shape and color of the lion’s paws. The lion head is usually over-sized and dragon-like, like many stone lions in China.

The Chinese lion dance is associated with good luck, power, strength, majesty and happiness.

Yin and Yang

The lion- and dragon- dance, for instance, is thought to recreate the breathing rhythm of a lion and thereby coordinate the interaction of yin and yang influences. The lion’s exhalation is believed to repel yin forces, and its inhalation to draw in yang forces from the surrounding area. In this way, the lion attracts yang and repels yin, thereby insuring the harmony of the environment, so it is also for the dragon dance.

Dragon Dance

The origin of the 耍龙灯 shuǎ lóng dēng,Dragon Dance can be dated back to the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD). It was then used in a ceremony for worshiping ancestors and praying for rain.

The dragons body is woven in a round shape of thin bamboo strips, segment-by-segment, and covered with a huge red cloth with dragon scales decorating it. The whole dragon is usually up to 30 meters in length — and people hold rods every 1 to 2 meters to raise the segments.

Chinese dragons symbolize wisdom, power and wealth, and they are believed to bring good luck to people.

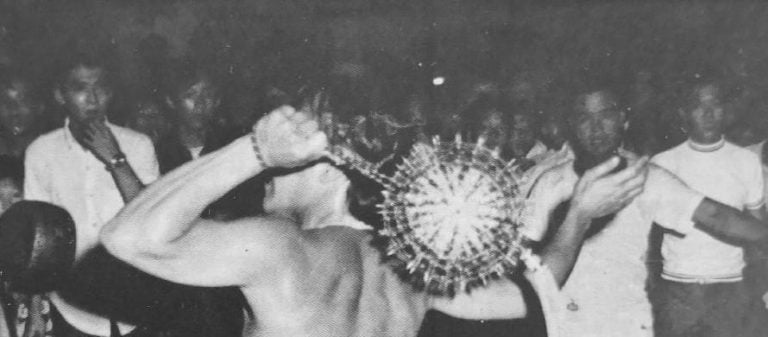

Spirit medium possession

A performance in which the spirit mediums kick a red-hot iron ball or swing a spiked sphere also attracts yang and repels yin, thereby insuring the harmony of the environment. The kicking and swinging motions are supposed to represent the incandescent state of the primal universe, inducing yin and yang to produce the five elements and all things made thereof. The underlying purpose is to ensure the equilibrium of the universe in which humans live.

In Weld Quay, the priest invokes the spirits of the Nine Emperor Gods and invites them to descend into the urn. When the sacred ashes in the urn burn vigorously, it is a sign that the gods have arrived. The urn is then carried back to the temple and kept from public view.

Purification Rituals

Throughout the nine days of festival, the constant tinkling of a prayer bell and chants from the temple priests can be heard. Most devotees and prayers will stay at the temple, eat vegetarian meals and recite continuous chanting of prayers with incense and candles.

Worship rituals often include the offering of tea, fruit, flowers, and money, and the sacrificial burning of joss sticks, white candles, incense papers, paper images, charm papers, and other ritual paraphernalia. The worshipers ask for the blessings of Tou Mu – The Goddess of the North Star and the Nine Emperoe Gods.

Worship also usually includes adding oil to temple lamps (or making offerings for the purchase of oil) and performing divinations (bobei 卜貝) to ascertain the Nine Emperor Prods’ response to prayers, vows, offerings, and sacrifices.

When devotees are blessed with good fortune they perform the luck-maintaining ritual to consolidate their position; when they encounter ill fortune, they participate in the ill-luck dissolving ritual to remove bad influences and usher in the good; when their luck turns for the better following the ill-luck dissolving ritual, they participate in the thanksgiving ritual to show their gratitude to the Divine Nine’s intervention.

Spirit medium possessions, the bridge-crossing, fire-walking purification ritual and sitting on spiked thrones edged with swords are also associated with the celebration of this festival.

Bridge-crossing ceremony and fire-walking ceremony

The bridge-crossing ceremony is held on the evening of the festival’s eighth day. A rather rickety bridge is set up in the temple grounds; in the central states of Peninsular Malaysia the bridge is made of wood and

measures 6.5 meters long,1 meter high, and 1.2 meters wide, while in the northern states it is made of steel and is either raised to a height of some twenty meters (like a hanging bridge) or placed on a platform and laced with sword blades.

People believe that crossing the bridge without incident is a clear sign that their good fortune and their standing with the star deities are assured. The participants receive charms, yellow threads or a Jiu Huang Ye seal stamped on their clothing to ward off the evils of the past year.

The bridge-crossing ceremony represents the surmounting of yin (since water is highly yin), while the fire-walking ceremony represents the acceptance of yang (since fire is highly yang).

By crossing the bridge the devotees negate evil and acquire spiritual confidence and power, not only over themselves but also over the environment in which they live. The two ceremonies are thus mutually inclusive purification rituals that are interrelated in meaning.

The fire-walking ceremony is held on the evening of the ninth day of the celebration. One hundred sacks of charcoal are used to prepare the fire-walking bed, which measures 3.5 meters long, 1.2 meters wide, and 0.6 meters high. Some fifteen men are employed for the laborious task of preparing the bed, which requires more than seven hours. All spirit medium and other participants are barefoot, and each carries a rolled-up yellow pennant of the Nine Emperor Gods to protect him from harm.

They must be ritually clean, having abstained from sex and observed a vegetarian diet for the past nine days. They are not allowed to wear leather belts and metal objects, including rings and belt buckles, as these objects are highly repugnant to the spirits.

Most participants in the fire-walking ceremony (and in the bridge-crossing ceremony as well) express the significance of the ritual with the word guoyun 過運,which they explain as meaning

“to cross over ill luckand usher in good luck.”

By walking over the fire the religious virtuosi, by virtue of their ritual purity, enact the victory of good over bad, mind over matter. As they purify themselves over the fire, the whole community, whose state of purity these spiritual mediums represent, is by magical implication cleansed of all evil influences.

Impaling ceremony

This tradition doesn’t exist in China and is believed to have been adopted from the Indian festival of Thaipusam.

Religious devotees and spirit mediums will also get pierced through cheeks, with 4.5 meter spears, hooks are placed on the back an limbs, chest, stomach and tongue are slashed with swords and knives, some wash themselves with hot oil.

Surprisingly, little to no blood is spilled throughout the rituals.

This is quite a sight and we wonder how these mediums withstand the pain.

Being possessed by one of the Nine Emperor Gods spares them from pain, this are acts of faith, devotion and humility.

Sending-off ritual

The festival officially concludes with the lowering of the jiuqudeng on the 10th day.

The ritual to send off the gods starts on the ninth day with the transfer of the sacred urn to the sedan chair, and a procession to the sea. A chariot sets off from the main temple in the heart of George Town and passes by several temples on the way to the waterway in Weld Quay.

The procession is accompanied by lion dancers, stilt walkers and musicians playing drums, cymbals and gongs. At the river, the Taoist priest conducts the ceremony to send off the gods.

The sending-off ceremony typically involves the dispatch of the Emperor Gods in a miniature boat or real sampan loaded with such items as beans, rice, sugar, salt, flour, incense, and other ritual items.

The flaming jiuqudeng or urn is placed in a small boat on the river, and everyone waits silently for the boat to move, indicating the gods’ departure. As the boat is launched the incense ashes accumulated during the previous year are tossed into the water, also to symbolize the departure.

This is followed by the ending of the vegetarian ritual in which six bowls of raw pork are offered to the White Tiger Deity (Bai Hu Ye, or Baihuye 白虎爺), red candles are lighted.

George Town- Penang

George Town, is a part of Penang Island and a historic city of the Straits of Malacca. Together with Malacca they are UNESCO World Heritage sites, we visited Malacca and lived in Penang for several months.

Penang bears testimony to a living multi-cultural heritage and tradition of Asia, where many religions and cultures coexist. Reflecting the coming together of cultural elements from the Malay Archipelago, India and China with those of Europe, to create a unique architecture, culture and townscape. George town has developed over 500 years of trading and cultural exchanges between East and West.

Named after Britain’s King George III, George Town was strategically located to participate in the trade with the expanding British Empire and some of the city still reflects that past. However, nowadays it is a predominantly Malaysian- Chinese city, with all of the bustle and color that this implies, which also blends in Little India, center of the Indian community, and Kampung Siam – an area bequeathed by the East India Company on behalf of Queen Victoria to the Thai and Burmese communities in 1845.

The heart of George Town offers a unique blend of British colonial, Chinese, Indian, Malay and Thai contributions, including an impressive collection of Chinese shop houses and British mansions, Chinese clan houses, markets, Buddhist, Taoist and Hindu temples, mosques and churches.

In among this rich multi-cultural heritage come equally strong multi-cultural food influences and fusion, easily making George Town the food capital of Malaysia and, many argue, center of by far the best street food in Asia. In George Town street food is not just a necessary part of the day but a culinary experience, unique to this beautiful city. Around The Nine Emperor Gods Festival the Chinese footstalls will sell only vegetarian meals, being it a vegetarian festival.

In Penang, stories abound about a Fujian fisherman who spoke to the brothers as they ascended to the heavens from the sea. When he brought their advice to Penang, it saved the people from a serious epidemic.

There is also a tale originating from Hong Kong Street about how young men used to hide from Japanese soldiers during World War II behind yellow curtains in the temple, where they were protected by the Nine Emperors.

No matter what the folklore, devotees respect the Nine Emperors as guardians who have the ability to confer luck, wealth and longevity. By following strict practices of worship throughout the nine days, devotees believe that they will receive the blessings of the Gods.

Witnessing this festival I am filled with conviction that religious celebrations help comunities to achieve peace and harmony within themselves while at the same time maintain a sense of continuity between the past, present and future. The significance of these sentiments is clearly represented in the myths, rituals and symbolism that dominate the Nine Emperor Gods festival.

Myths and Folklore of the Nine Emperor Gods Festival Celebration in Georgetown- Penang, are only the tip of the iceberg. There are many more stories and interesting traditions to be discovered. Read about The Chinese New Year celebration in Penang- Georgetown

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- Cheryl Sim. Singapore Infopdia.

- Chinese New Year Dragon Dance.

- Chinese New Year Lion Dance.

- DeBernardi Jean Elizabeth. Penang: Rites of Belonging in a Malaysian Chinese Community.

- http://www.nine-emperorgods.org/legend/

- https://www.academia.edu/618483/The_Nine_Emperor_Gods_at_the_border_transnational_culture_alternate_modes_of_practice_and_the_expansion_of_the_vegetarian_festival_in_Hat_Yai_Macquarie_University_?auto=download

- https://www.gutenberg.org/files/15250/15250-h/15250-h.htm#d0e4585

- Image by: Tourism Malaysia,

- Meet the Gods of Chinese New Year.

- Melacca and George Town, Historic Cities of the Straits of Malacca. UNESCO.

- Nine Emperor Gods Festival. https://web.archive.org/web/20220128054536/http://cheryljhoffmann.com/category/9emperor/ incredible photo art!

- Nine Emperor Gods Festival. recommended!

- Spirits of the nine emperor gods. Immage https://www.nst.com.my/lifestyle/sunday-vibes/2018/10/421278/spirits-nine-emperor-gods

- The Chinese New Year celebration.

- The Festival of the Nine Emperor Gods in Malaysia

- Werner Edward T.C.. Myths and Legends of China. 1922. sacred-texts.com

- Yellow ‘mee koo’ – buns picture. https://where2magazine.com/nine-emperor-gods-festival/