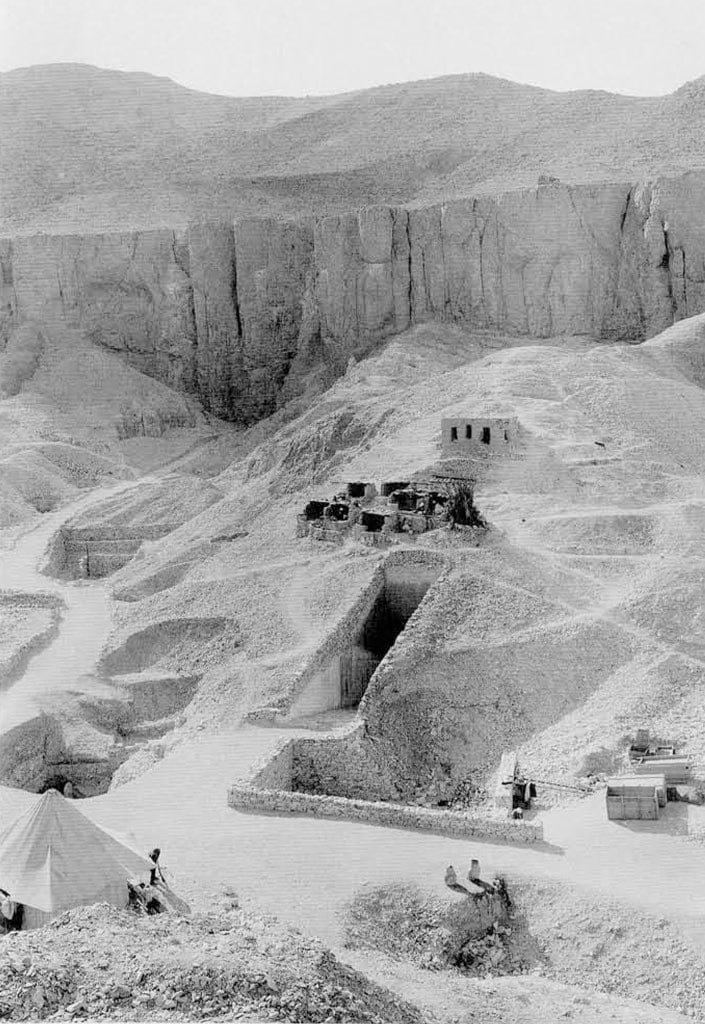

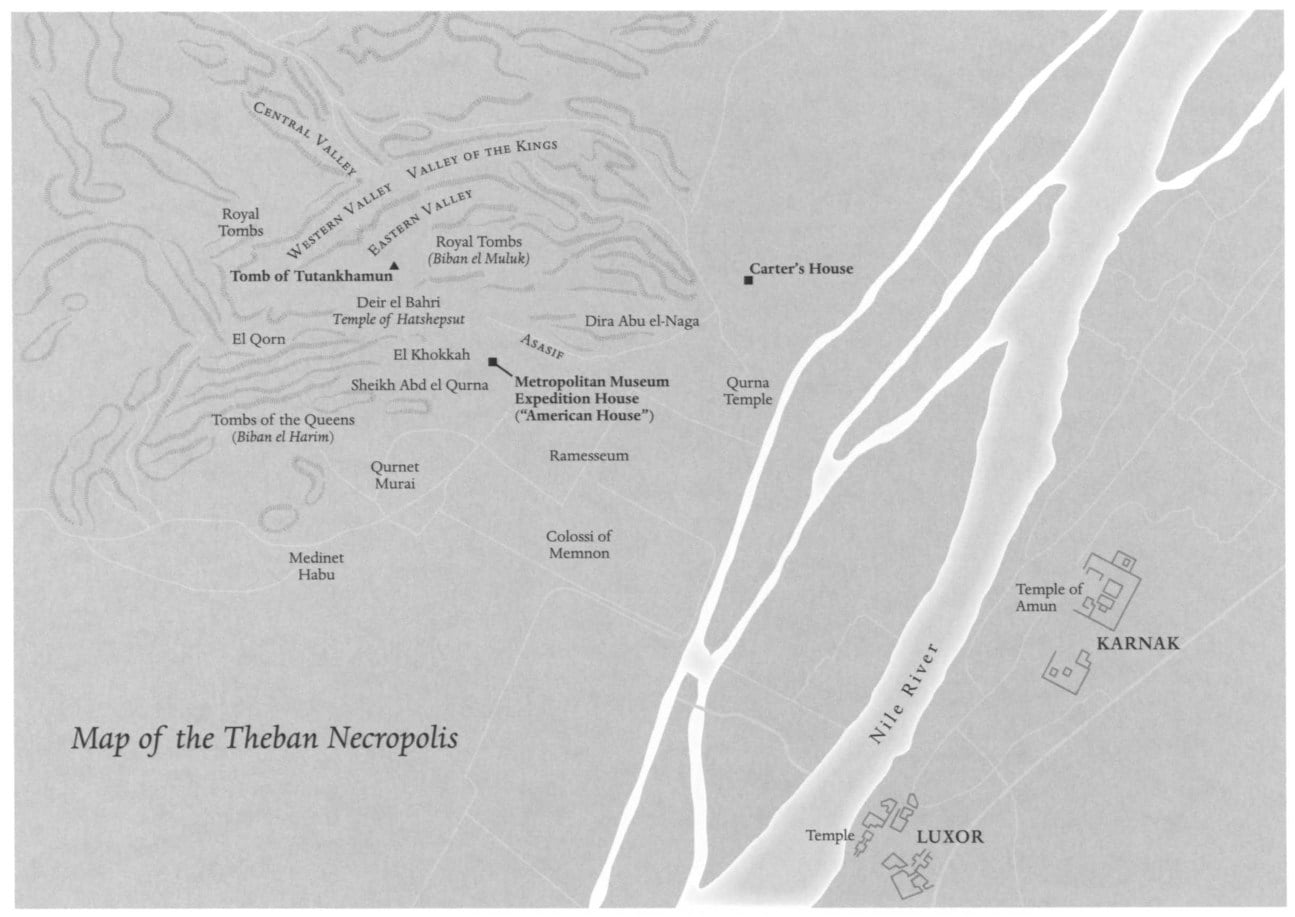

British Archaeologist and Egyptologist Howard Carter along with his sponsor, Lord Carnarvon, discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun (Tutankhamen) in 1922, in the Valley of the Kings at Luxor.

Rumor and speculation of mysterious deaths began to spread. Discover the life of King Tut, and the Curse of the Pharaoh, Tutankhamun or, the Mummy’s Curse.

In this Article

Visiting the Egyptian Antiquities Museum after the Arab Spring

2012. The streets are silent, Tahrir Square is nearly empty, signs of the Egyptian Arab Spring remain. Like the large Ritz-Carlton sign announcing the opening of the new hotel beside the Egyptian Antiquities Museum and the still-empty burned out National Party headquarters.

As we pay the entry fee, I look around – just the two of us and a Japanese tourist and his constantly working camera click, click, click… I think of destruction and hear the sound of shattered glass instead, and imagine the shouts of the staff, during the tumultuous days of late January 2011.

The Arab Spring was in full bloom, with pro-democracy uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt inspiring similar revolts throughout the Arabic world. There was a regime change in Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, and Yemen, and repression and/or violence in Syria, Bahrain, Sudan, and elsewhere. Here protests and strikes began on January 25, 2011 (National Police Day) and lasted for 18 days.

Zahi Hawass, the Minister of Antiquities, announced that though the museum security had been breached, antiquities had been stolen, damaged and some recovered. He noted that the biggest threat to the Museum was from the fire next door. Hawass also acknowledged that Egyptians protected the museum and helped to apprehend the bandits, he wrote:

“What is really beautiful is that not all Egyptians were involved in the looting of the museum. A very small number of people tried to break, steal and rob. Sadly, one criminal voice is louder than one hundred voices of peace.

The Egyptian people are calling for freedom, not destruction. When I left the museum on Saturday, I was met outside by many Egyptians, who asked if the museum was safe and what they could do to help…

Due to the circumstances, this behavior is not surprising; criminals and people without a conscience will rob their own country. If the lights went off in New York City, or London, even if only for an hour, criminal behavior will occur. I am very proud that Egyptians want to stop these criminals to protect Egypt and its heritage.”

Later it was confirmed that 70 objects were knocked over or damaged and 18 items were missing from the museum. Most probably stolen by professional international art thieves…

I wish the course of the Pharaoh gets them… the power of superstition is great indeed.

This museum represents the finest antiquities from Egypt’s Pharaonic past. It chronicles a civilization that remains the pinnacle of ancient learning, sophistication, art and creativity. Asking about the looting we are told,

“They were looking for quick money, no antiques were stolen, only the museums shop was raided.”

It feels strange, an empty museum has something – something ghostly and something more, – the luxury to enjoy the exhibits without any disturbance by other visitors.

The Egyptian Museum is the oldest archaeological museum in the Middle East, and houses the largest collection of Pharaonic antiquities in the world, housing over 170,000 artifacts. It has the largest collection of Pharaonic antiquities in the world.

The Museum’s exhibits span the Predynastic Period to the Graeco-Roman Era (c. 5500 BC – AD 364). It was inaugurated in 1902 by Khedive Abbas Helmy II, and has become a historic landmark in downtown Cairo, and home to some of the world’s most magnificent ancient masterpieces.

The treasures include Amarna Period relics, like reliefs, statues, sarcophagi, mummies, papyri, funerary art and the contents of various tombs as well as unique jewelry and ornaments.

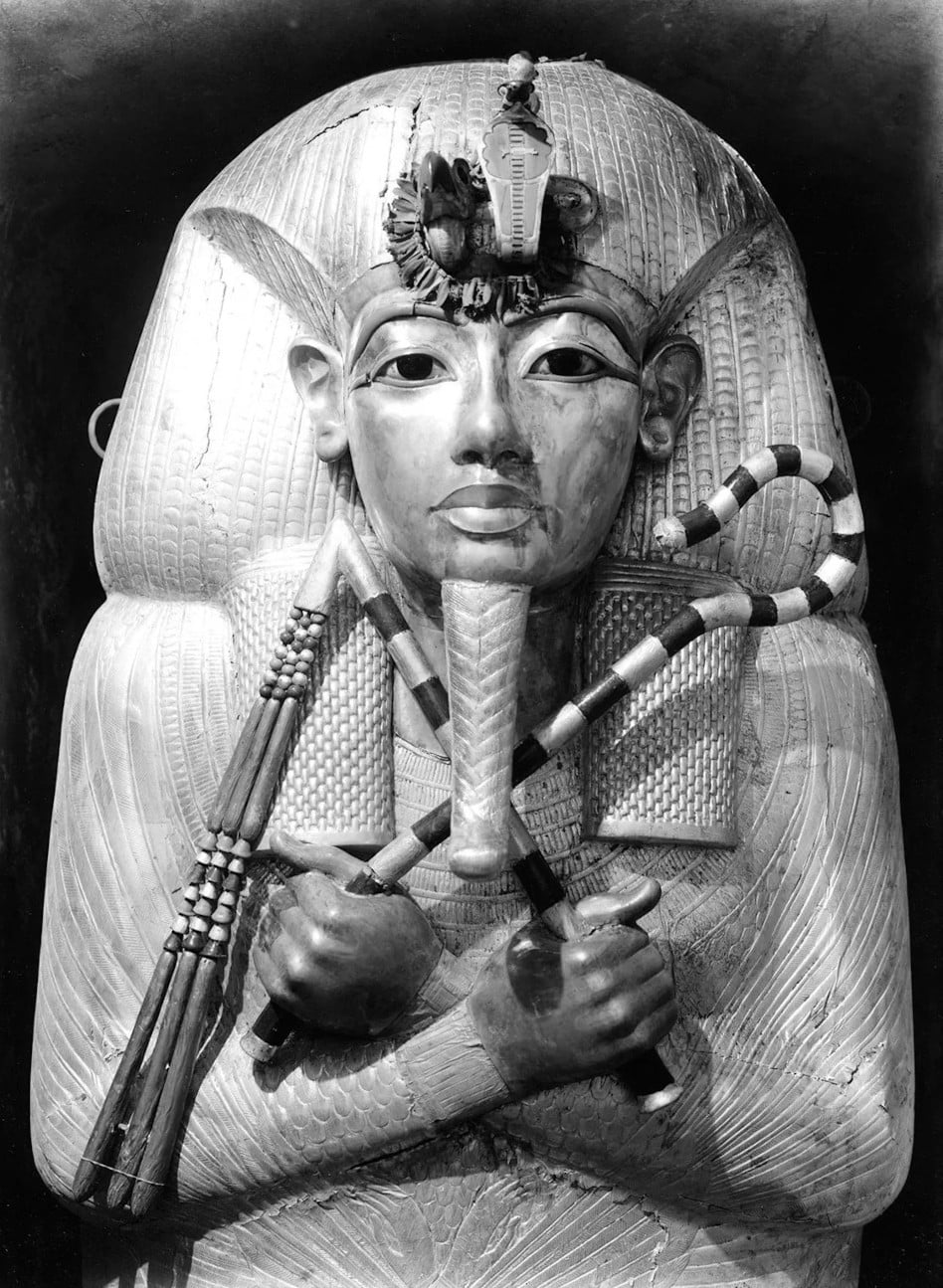

And there he is Tut – the boy we are here for. His tomb, in comparison with his contemporaries, was modest.

After his death, his successors made an attempt to expunge his memory by removing his name from all the official records. Even those carved in stone. As it turns out, his enemy’s efforts only ensured his eventual fame. His name was Tutankhamun: King Tut.

HISTORY: Pharaoh Tutankhamun

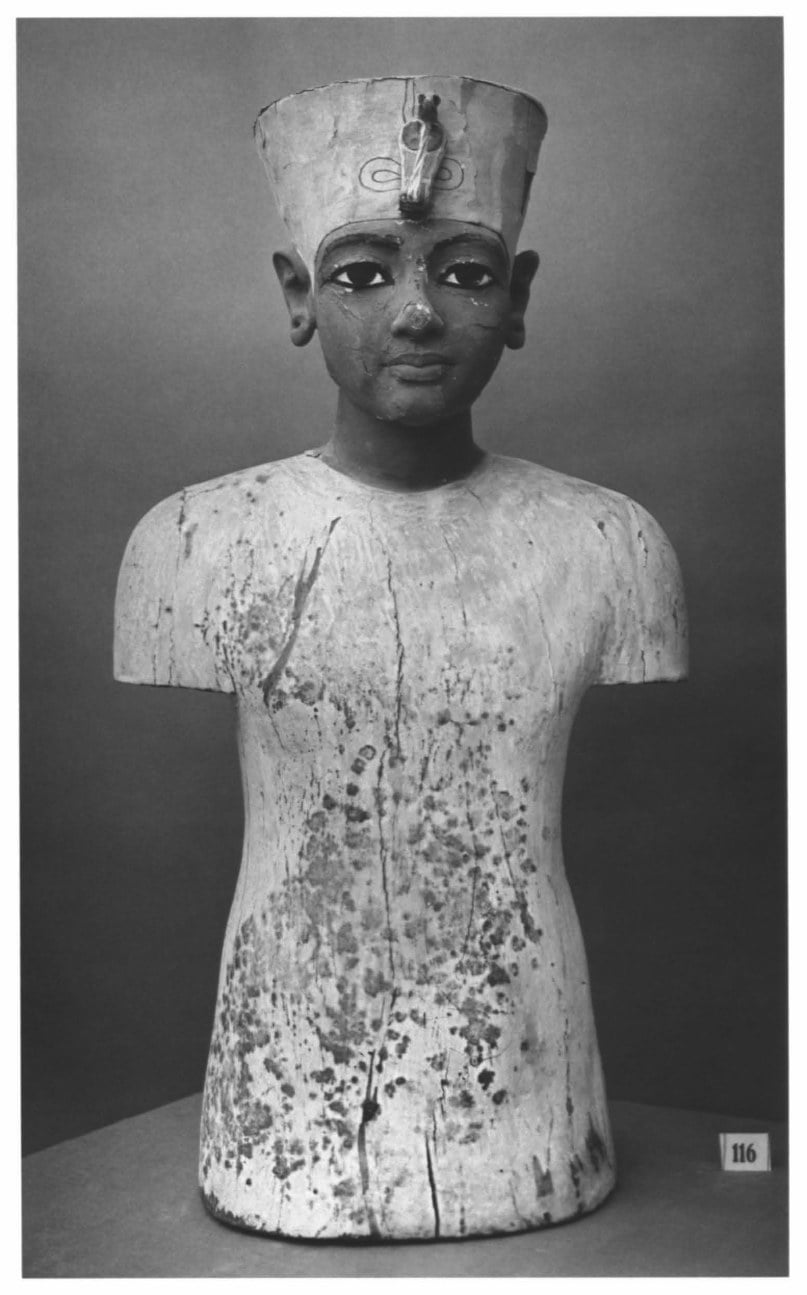

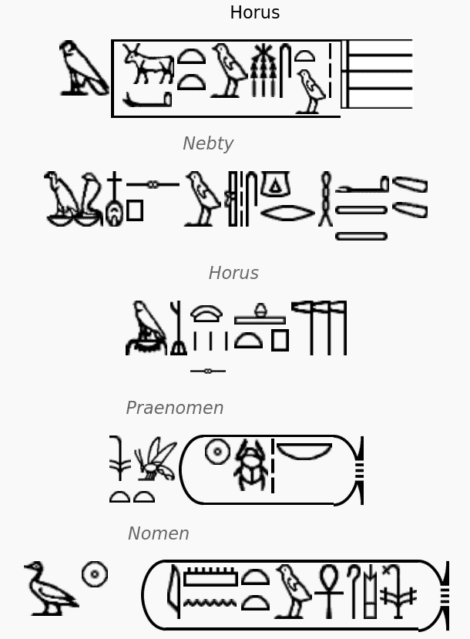

Public domain, edited.

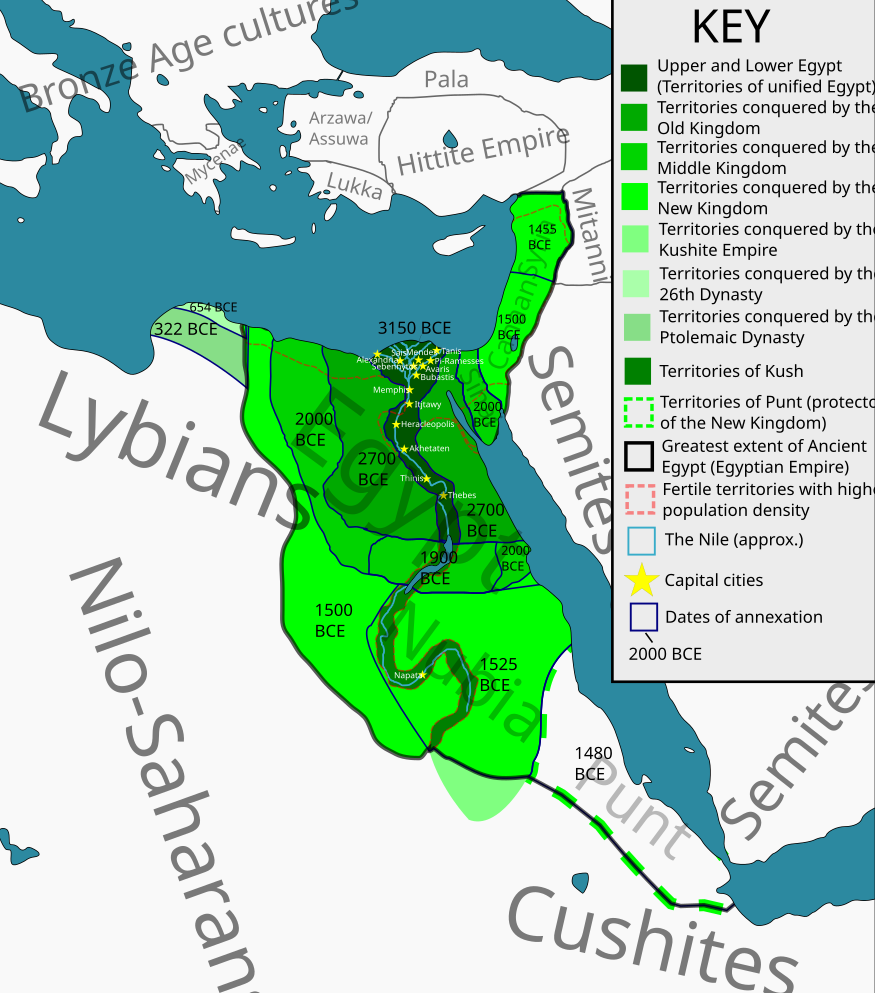

Tutankhamun was an Egyptian pharaoh of the 18th dynasty (ruled ca. 1332–1323 BC in the conventional chronology), during the period of Egyptian history known as the New Kingdom.

DNA testing on Tutankhamun’s mummy in 2010 showed that Tutankhamun was a frail young man whose father and mother were siblings. His father, Akhenaten, had conceived a son with his own sister, the so-called Younger Lady found in the tomb of Amenhotep II (KV35). Such marriages were a royal prerogative; it kept the noble pedigree pure and reduced the risk of ambitious in-laws making claims to the throne.

Tutankhamun died young, leading many scholars to speculate on the manner of his death – a chariot accident; or a kick by a horse; septicemia or fat embolism secondary to a femur fracture; murder by blow to the head; poisoning and even a hippopotamus attack!

New molecular genetic analysis show, that Tutankhamun had multiple disorders, and some of them might have reached the cumulative character of an inflammatory, immune-suppressive – and thus weakening – syndrome.

He might be envisioned as a young but frail king who needed canes to walk because of the bone-necrotic and sometimes painful Köhler disease II, plus oligodactyly (hypophalangism) in the right foot and clubfoot on the left.

There is evidence that Tutankhamun may have had this impairment for quite some time. The walking disability can be substantially aided by the use of a cane. Howard Carter discovered 130 whole and partial examples of sticks and staves in the king’s tomb, supporting the hypothesis of a walking impairment.

Traces of wear can be seen on a number of the sticks, demonstrating that they were used in the king’s lifetime. Additional evidence for some sort of physical disability is found in a number of images from Tutankhamun’s reign that show him seated while engaged in activities for which he normally should have been standing, such as hunting.

A sudden leg fracture, possibly introduced by a fall might have resulted in a life-threatening condition when a malaria infection occurred. Seeds, fruits, and leaves found in the tomb, and possibly used as medical treatment, support this diagnosis.

He married his half-sister, Ankhesenamun, but they did not produce an heir. This left the line of succession unclear. Tutankhamun’s much-older advisor (and possible step-grandfather), Ay, married the widowed Ankhesenamun and became pharaoh.

Etymology: Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun was not, however, the name by which his people knew him. Like all of Egypt’s kings, Tutankhamun actually had five royal names. Officially, he was:

Tutankhamun’s original nomen: Tutankhaten translated as; Living-image-of-Aten The-life-of-Aten-is-pleasingTo be perfect/completeOne-perfect-of-life-is-Aten.

Horus Name: Ka nakht tut mesut, translated as; Victorious bull, the (very) image of (re)birth.

His second full nomen (also called the Son of Re Name) was; Tut ankh imen, heqa iunu shemau, translated as; The living image of Amun, Ruler of Southern Heliopolis.

Tutankahmun’s Nebty or Two Ladies Name was:

- Nefer hepu, segereh tawy, translated as; Perfect of laws, who has quieted down the Two Lands.

- Nefer hepu, segereh tawy sehetep netjeru nebu, translated as; Perfect of laws, who has quieted down the Two Lands and pacified all the gods.

- Wer ah imen, translated as; The great one of the palace of Amun.

Tutankhamun’s Gold Falcon Name was:

- Wetjes khau, sehetep netjeru translated as; Elevated of appearances, who has satisfied the gods.

- Wetjes khau it ef ra, translates as; Who has elevated the appearances of his father Re.

Tutankhamun’s Prenomen or Throne Name was: Neb kheperu re, translated as: The possessor of the manifestation of Re. Wwhich had an epithet added: Heqa maat, translated as; Ruler of Maat.

Cartouche left: “Tutankhamun, ruler of Upper Heliopolis”.

Right: Prenomen “Nebkheperura”

His people; however knew him by his throne name, Nebkheperure (Nebkheperura), which literally translates as “[the sun god] Re is the lord of manifestations”.

He is colloquially referred to as King Tut and possibly also the Nibhurrereya of the Amarna letters, and likely the 18th dynasty king Rathotis who, according to Manetho, an ancient historian, had reigned for nine years.

The discovery of the tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamun

Painstakingly excavated over the course of almost ten years, the tomb’s four small rock-cut chambers hidden beneath the sands of the Valley of the Kings yielded over 5,000 incredible objects, bearing witness to the life and death of this king. The tomb of King Tut was one of the most spectacular discoveries in the history of archaeology.

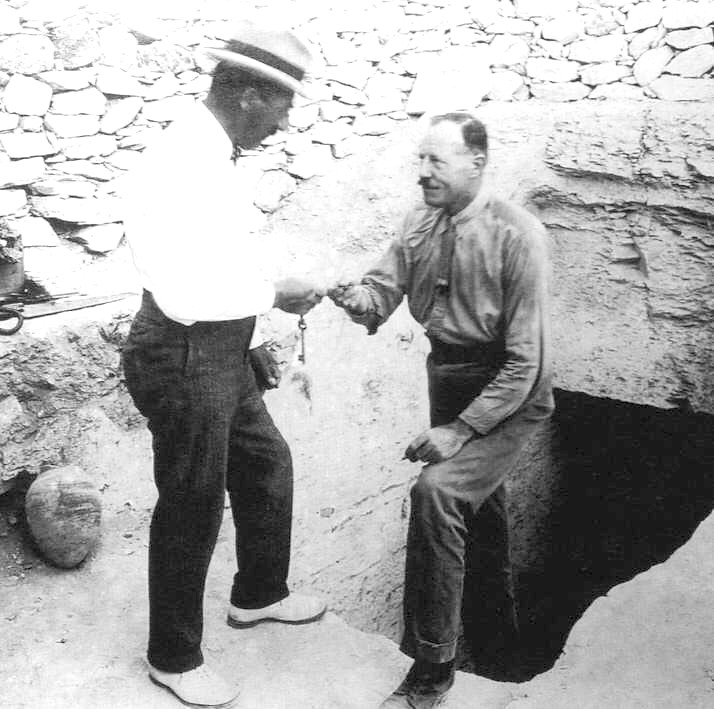

Credit for discovery of the tomb was given to Howard Carter, in December 1922 he found the tomb of Tutankhamen.

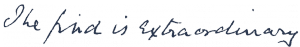

On November 6, Carter sent a telegram to Lord Carnarvon, his financier, in England:

“AT LAST HAVE MADE WONDERFUL DISCOVERY IN VALLEY. A MAGNIFICENT TOMB WITH SEALS INTACT. RE-COVERED SAME FOR YOUR ARRIVAL. CONGRATULATIONS.”

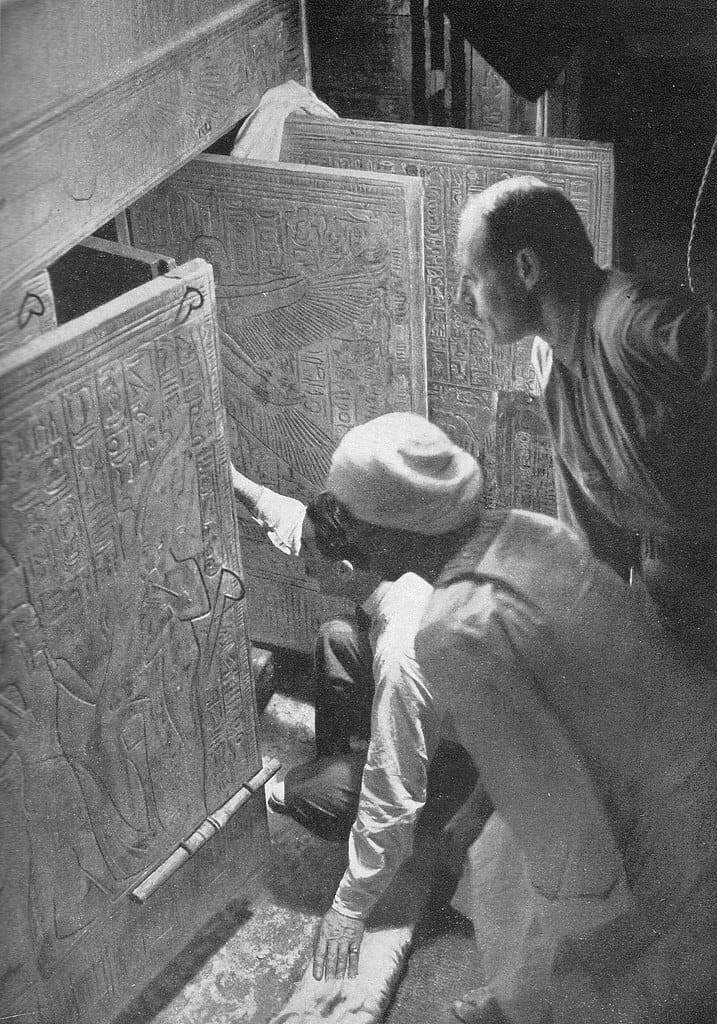

Carnarvon went to Egypt and 20 days later the entrance to the tomb was excavated and Carter entered, with Lord Carnarvon, Lady Evelyn Herbert (Carnarvon’s daughter), and an assistant.

This is Lord Carnarvon’s own account of the discovery in a letter to Egyptologist Sir Alan Gardiner:

So far it is Tutankamon beds boxes & every conceivable thing there is a box with a few papyri in – the throne of the King the most marvellous inlaid chair you ever saw – 2 life size figures of the King bitumenised (sic) – all sorts of religious signs hardly known up to date[.]

The King[‘s] clothing rotten but gorgeous. Everything is in a very ticklish state owing to constant handlings & openings in ancient times (I reckon on having to spend 2000£ on preserving & packing)…

The most wonderful ushabti in wood of the King…wood portrait head ditto endless staves etc. some with most wonderful work…

4 chariots The most miraculous alabaster vases ever seen 3 colossal beds of honour with extraordinary animals…

There is a further room so packed [or “hacked” ?] one cannot see really what is there – Some of the boxes are marvellous chairs numerable a wonderful stool ebony & ivory…

I imagine it is the greatest find ever made…

Tomorrow the official opening [Wednesday 29th November 1922]…

I have between 20 & 30 soldiers police & gaffirs to guard.

The Tutankhamun Collection at the Museum: Gilded Treasures of King Tut

The second floor of the museum is filled with marvels from the tomb of the boy King Tut. Tutankhamun has captivated audiences worldwide since the discovery of his tomb back in 1922. He has become an international icon of Egyptian civilization. Around 5000 pieces were found inside the tomb; vessels, coffins, tabernacles, statues and of course, his famous gold mask and his renowned throne.

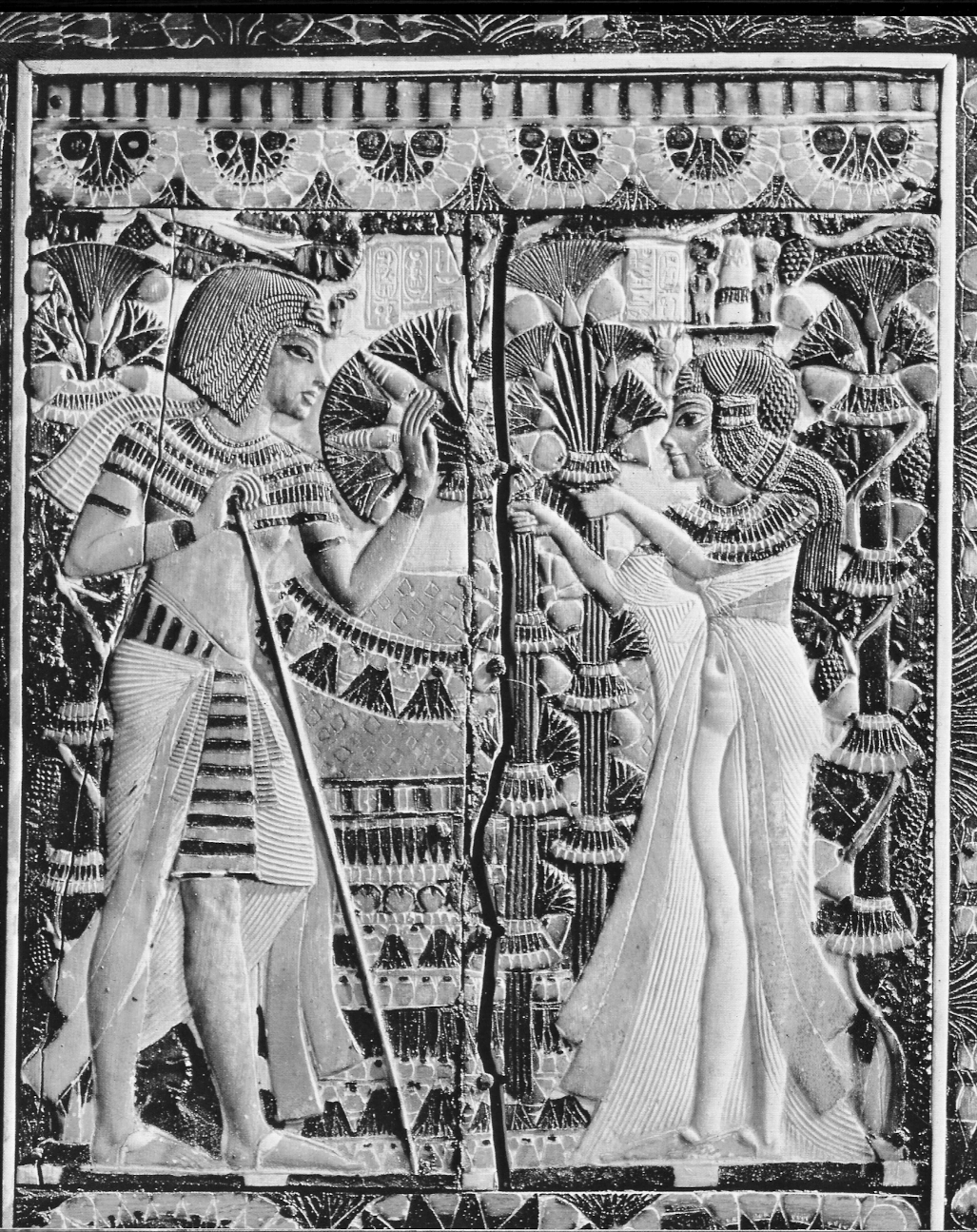

Made of wood and covered with gold leafing, silver, glass and semi-precious gemstones, the legs of the throne, simulate lion claws and present the heads of two of these animals in the front part, while the armrests show symbols of the unification of Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt such as the double crown and the cobras.

The back of the throne shows one of the most famous and intimate scenes in Art History: the young pharaoh appears sitting and being regaled with an ointment by his wife Ankhesenamon.

Roland Unger. CC -BY-SA 3.0., edited.

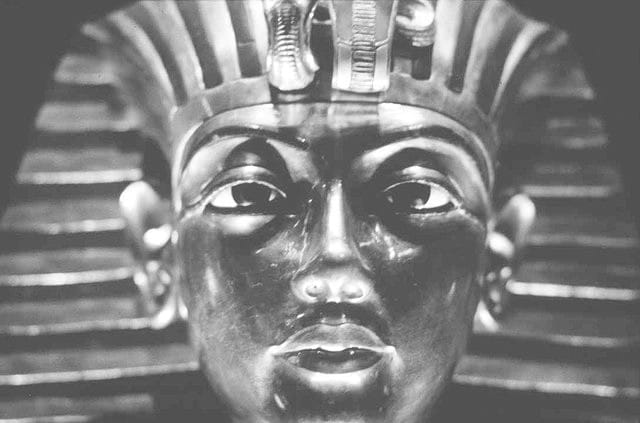

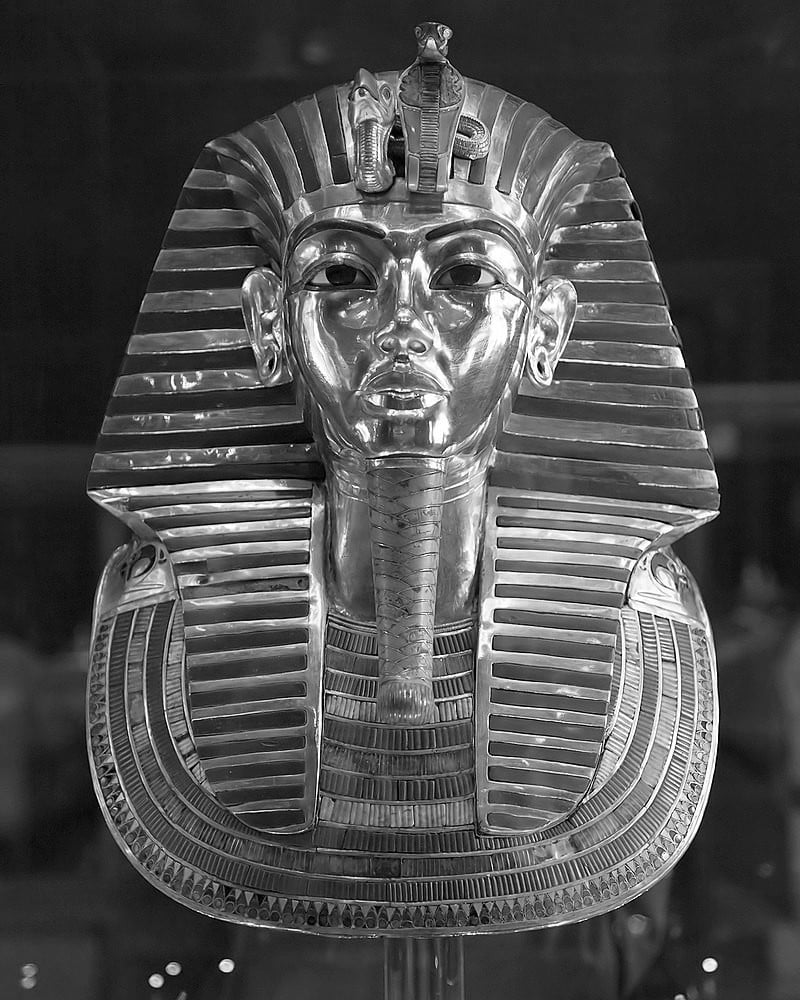

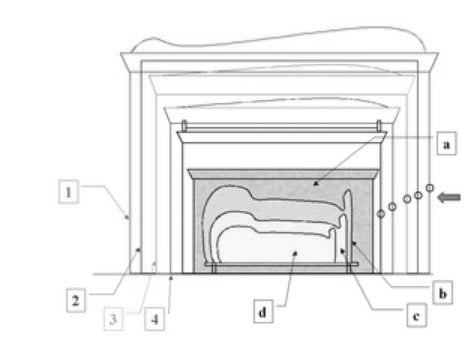

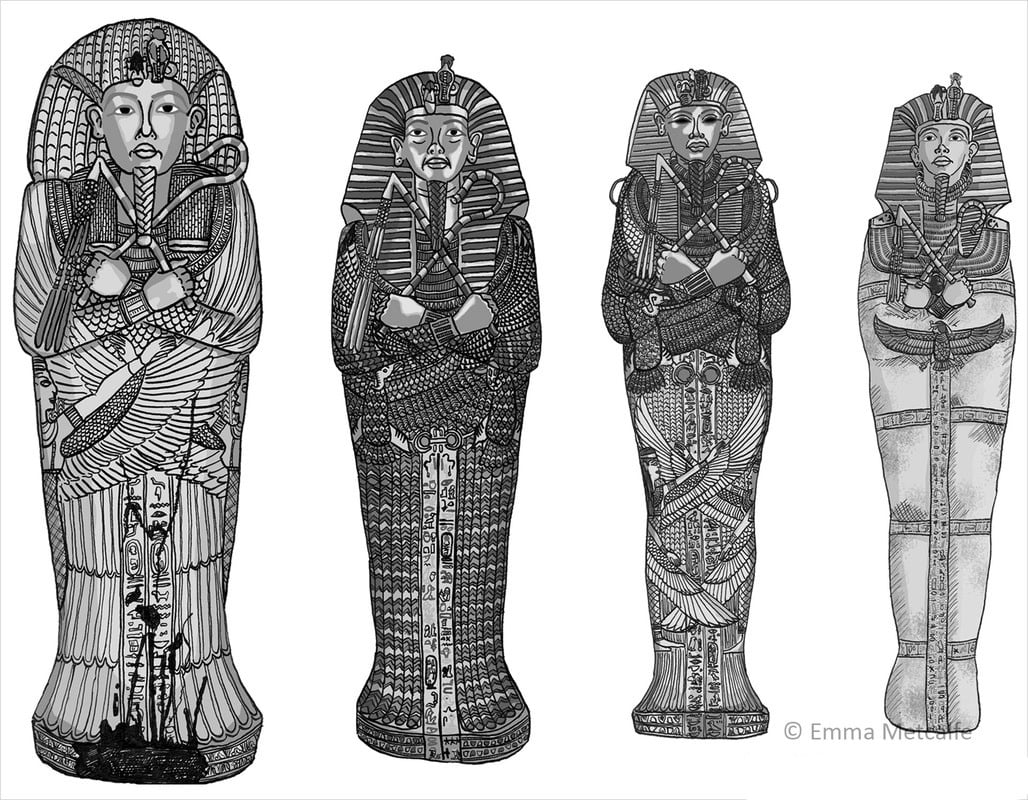

On the king’s head was a magnificent golden portrait mask, and numerous pieces of jewelry and amulets lay upon the mummy and in its wrappings. The coffins and stone sarcophagus were surrounded by four text-covered shrines of hammered gold over wood, which practically filled the burial chamber.

The other rooms were crammed with furniture, statuary, clothes, chariots, weapons, staffs, and numerous other objects. The numerous treasures on display include golden bows and painted arrows, musical instruments crafted from precious metals and majestic jewelry.

His remarkable nested burial chambers, plated in gold, are stunning works of art. Inside, the king’s mummy lay within a nest of three coffins, the innermost of solid gold, the two outer ones of gold hammered over wooden frames.

The splendor of Tut’s belongings is unparalleled also because the tomb was untouched by grave thieves before it was opened.

It is said that pharaonic tombs had special protection…

The power of superstition is great…

MODERN MYTH: THE CURSE OF THE PHARAOH

During the last hundred years, the phrase “curse of the pharaohs” has been used to describe the cause of a large assortment of ills. These range from natural disasters to a mild stomach disorder that often plagues tourists to Egypt – also known as “pharaoh’s revenge,” or “gippy tummy” – derived from Egyptian mummy.

When the team discovered the Tomb of Tutankhamun, in the Valley of the Kings on the West Bank at Luxor, rumor and speculation of their mysterious deaths began to spread. Stories suggest that anyone who disturbed the mummy of an ancient Pharaoh will be haunted by bad luck, illness or even death.

The origin of King Tutankhamun’s curse

“Cursed be those that disturb the rest of Pharaoh. They that shall break the seal of this tomb shall meet death by a disease which no doctor can diagnose.”

This would later become one version of the famous “Curse of the Pharaoh”. The curse does not differentiate between thieves and archaeologists.

When Howard Carter and his nameless Egyptian Helpers discovered King Tutankhamun’s tomb in late 1922, he immediately telegraphed his financier in England, Lord Carnarvon, who came to the valley of the kings, along with his daughter, Evelyn Herbert. All three were present when Carter broke a little hole in the tomb’s doorway.

Carter wrote:

“With trembling hands I made a tiny breach in the upper left-hand corner. Darkness and blank space, as far as an iron testing-rod could reach, showed that whatever lay beyond was empty, and not filled like the passage we had just cleared.

Candle tests were applied as a precaution against possible foul gases, and then, widening the hole a little, I inserted the candle and peered in, Lord Carnarvon, Lady Evelyn and Callender standing anxiously beside me to hear the verdict.

At first I could see nothing, the hot air escaping from the chamber causing the candle flame to flicker, but presently, as my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room within emerged slowly from the mist, strange animals, statues, and gold – everywhere the glint of gold. For the moment – an eternity it must have seemed to the others standing by – I was struck dumb with amazement, and when Lord Carnarvon, unable to stand the suspense any longer, inquired anxiously,

“Can you see anything?” asked Carnarvon.

“Yes, wonderful things,” Carter tremblingly replied.

It is said that when Carter arrived home that night his servant met him at the door. In his hand he clutched a few yellow feathers. His eyes large with fear, he reported that the canary had been killed by a cobra. Carter, a practical man, told the servant to make sure the snake was out of the house. The man grabbed Carter by the sleeve.

“The pharaoh’s serpent ate the bird because it led us to the hidden tomb! You must not disturb the tomb!”

Scoffing at such superstitious nonsense, Carter sent the man home.

The power of superstition is great…

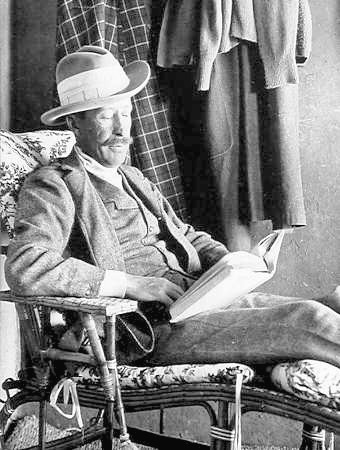

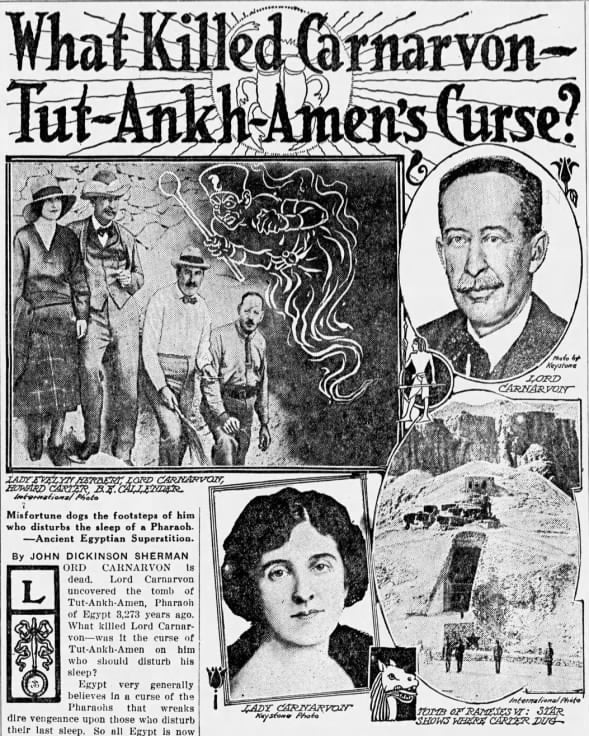

The death of Lord Carnarvon

After cutting a mosquito bite on his cheek while shaving, Lord Carnarvon grew ill, then died April 5 in a Cairo hotel – less than a year after the discovery of the tomb.

As he breathed his last, power went out all over the city. The rumor of a mummy’s curse was born.

The press reported: At the very moment of Carnarvon’s death all the lights in Cairo had been mysteriously extinguished and at his English home Carnarvon’s dog, Susie, let out a great howl and died.

The power of superstition is great…

The loss of electricity in Cairo; however, is not an uncommon occurrence, and is an experience, that most tourists to Egypt, have encountered several times. Given the time differences rather than dying simultaneously, Susie actually died four hours after her master.

Lady Carnarvon adds in an interview from 2009:

“It was quite eerie because the golden mask of Tutankhamun is one of the most famous symbols and it’s made of two completely even sheets of gold. It’s only thinner at one point – on the left cheek – and that was the left cheek where Lord Carnarvon was bitten by a mosquito and he later died of Septicemia.

Tutankhamun probably died of Septicemia as well and they were probably buried more or less at the same time of year, so the more I go into the stories the more extraordinary coincidences there are.”

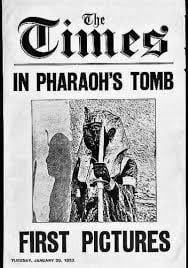

Lord Carnarvon sold the exclusive rights to publish anything about the tomb to the Times of London. It is pertinent to note that the estate of the deceased Lord Carnarvon continued to reap the benefits of the exclusivity arrangement made with the Times of London, receiving a percentage of the profits realized from the sale of stories. Keeping the interest of the public at fever pitch was a lucrative business for both the Times and Carnavon’s estate.

The University of Manchester Egyptologist Dr Joyce Tyldesley points out the real story of Lord Carnarvon’s death is far from sinister. The real story is not quite so dramatic, if no less tragic. He died of an infection that caused blood poisoning, and that the origin of this infection was a mosquito bite on the cheek, cut open by a razor during shaving.

Theses about the death of Lord Carnarvon

Natural phenomena in Tut’s tomb (or any tomb, for that matter) that could cause disease are molds or spores. It is a fact that paleontologists and microbiologists now suggest that mummies be examined by people wearing gloves and masks to prevent the spread of any infection. Indeed, the Philadelphia Inquirer recently ran an article on this topic, entitled “Thesis: Fungi, not a curse, killed the finders of King Tutankhamun’s Tomb” (July 30, 1985).

Of course, this theory does not account for Carter’s remarkable resistance to the micro-organisms, not to mention the workers and scientists attached to the project, officials, and tourists who also survived.

However, other stories were simply invented by the press.

Like the suggestion he could have been poisoned by inhaling ancient and toxic bat guano that was heaped on the tomb floor can be ruled out, as no bats had penetrated the sealed grave.

And finally, the idea that Carnarvon might have been killed by radiation within the tombs has become increasingly popular. However, there is no evidence to support this theory.

Curse or coincidence?

The power of superstition is great…

One story goes that Carter found an ancient clay tablet in the antechamber. When he later translated it, the inscription read:

“Death will slay with his wings whoever disturbs the peace of the pharaoh”.

Rumors later circulated that Carter hid the tablet immediately so it would not alarm his workers, he denied doing so.

Carters letter reveals he was so bitter that his sensational find had been overshadowed by superstitious stories that he ironically hailed Weigalls death 12 years later as a “blessing”.

Weigall was working for the Daily Mail, which was a rival of the London Times, and he was not able to get the scientific information from Carter on a daily basis because “The Times” had the exclusive of the archaeological sensation, so he had to be able to tell his readers a parallel story. Did Weigall invent the course?

Carter wrote, in 1934, addressed to Helen Ionides:

“The death of the Duchess of Alba was very sad-the more so, poor woman, she had been for years gradually fading away. T. B. [tuberculosis] is an awful disease. I fear I must admit that I have not the same sentiments with regard to Weigall.

In fact his death is a real blessing. For although he was a clever writer, he was cunning. His inventions had no basis and thus a menace to Archaeology. Those of them for temporary excitement and amusement at the expense of others. The “Tutankhamun Curse” was his invention.

Believed out of pique-a sort of vengeance-towards his loyal friend Lord Carnarvon who, because Weigall came out solely as correspondent of the Daily Mail, was obliged to treat him like the other newspaper correspondents. He was never at the opening of the discovery. He was the last of the correspondents to arrive, several minutes afterwards. But enough of this venom I must direct to a more pleasant subject.”

According to James Randi, in his book, An Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural:

“When Tuts tomb was discovered and opened in 1922, it was a major archaeological event. In order to keep the press at bay and yet allow them a sensational aspect with which to deal, the head of the excavation team, Howard Carter, put out a story that a curse had been placed upon anyone who violated the rest of the boy-king.”

Carter did possibly not invent the idea of a cursed tomb, and did nothing to prevent the press from continuing to develop the story. He would work on the contents of the tomb of Tutankhamun for the next decade without the intrusions of the public or the press thanks to the mummy’s curse.

The power of superstition is great…

Objects from the tomb were given as gifts to Carters friend Sir Bruce Ingram, whose house burned down not long after. After being rebuilt, the house then flooded.

MODERN MYTH: Curse of Tutankhamun – The Mummy’s Curse

The tomb was considered the best preserved and most intact Pharaonic grave ever found in the Valley of the Kings, and the discovery was eagerly covered by the worlds press. An exclusive deal with The Times left scores of journalists sitting in the dust outside with nothing to see and no one to interview.

Consequently, newspapers turned to all sorts of “experts” to comment on the tomb, including popular fiction authors like Arthur Conan Doyle. Most prominent of all was the popular novelist Marie Corelli, whose comments regarding the health of Lord Carnarvon helped to ignite rumors of a curse.

When Carter and his team dug up the pharaoh’s tomb, they are said to have unwittingly unleashed the mythical Mummy’s Curse.

Marie Corelli

In a report in The Express on 24 March 1923 about Lord Carnarvon’s health Marie Corelli wrote:

“I cannot but think that some risks are run by breaking into the last rest of a king of Egypt whose tomb is specially and solemnly guarded, and robbing him of possessions.

This is why I ask: “was it a mosquito bite that has so seriously infected Lord Carnarvon?”

When, just a few days later Lord Carnarvon succumbed to his illness, Marie Corelli was hailed as a clairvoyant and a legend was born.

The power of superstition is great…

Each newspaper around the world carried a story about Lord Carnarvons death from the mysterious and ominous forces unleashed from the tomb that he was responsible for opening. All sorts of related phenomena were also attributed to the action of the curse upon the defiler of the tomb.

Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes and himself a believer in the occult and at this time a very popular writer, announced that Lord Carnarvon’s death could have been caused by “elementals” created by Tut’s priests to guard the royal tomb, the “Curse of Tutankhamun,” or, the “Mummys Curse,” entered popular culture.

King Tutankhamun’s curse: Hungry for stories, reporters added ever more names to the list

However, the statistics surrounding the death rate of the team excavating King Tutankhamun is somewhat underwhelming, after 50 of the 58-strong team survived.

Carnarvon was the only member of the original Tutankhamun expedition who died early, but the deaths of people tangentially associated with the tomb or mummy, kept the story of the curse alive.

More rational explanations of these deaths were overlooked by the reporters, who could finally get a scoop and not have to wait for the Times to present their facts.

Throughout the world, the story of the death of Carnarvon was recounted in detail, though not necessarily with accuracy. Newspapers appear to have arbitrarily killed off many of the people surrounding the tomb’s discovery.

A month after Lord Carnarvons death, financier George Jay Gould I passed away of a high fever after visiting the tomb. So another man fell to the curse.

The press had another victim of the curse after the death of Carters conservator – A. C. Mace of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; the fact that Mace had had pleurisy for a long time did not appear to affect the storytellers.

Then the Egyptologist, archaeologist, and writer Weigall (whom Carter and Carnarvon had attempted to keep out of the tomb under any circumstances) died too, supposedly from the curse.

In 1923, Egyptian prince Ali Kemal Fahmy Bey, who had once visited the tomb, was shot and killed in London by his jealous French wife–another victim!

Another tomb visitor, Georges Bénédite of the Louvre, died in 1926 at age 69.

And Albert Lythgoe, the head Egyptologist at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, died in 1934 at age 66. He got linked to the curse because he had viewed Tutankhamun’s open sarcophagus 10 years earlier.

Soon the papers carried stories of curators and workmen from museums all over the world, who had neither visited the tomb nor come into close contact with any of its contents, but had nevertheless been struck down.

The power of superstition is great…

People who had taken artifacts from Egypt in the past for private collections were now sending them back or donating them to institutions because they feared the curse. Silverman notes how.

“nervous people began cleaning out their basements and attics and sending their Egyptian relics to museums in order to avoid being the next victim”.

Carter, it should be noted, died in bed of natural causes at the age of 67 (March 2, 1939), more than 17 years after he discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun. Lately, the curse has also hit Carters reputation. German Egyptologists claimed that he stole from Tuts tomb, then feigned ransacking by ancient looters.

ETYMOLOGY: What is a Mummy?

Mummy comes from the Latin Mumia, a borrowed name from the Arabic mūmiya (مومياء) and Persian word for bitumen “mummiya” derived from mum – wax. Early archaeologists believed bitumen had been used in the mummification process on account of the blackened state of the bodies. However, the use of bitumen has been recorded as early as the New Kingdom (1550-1069 BC), it was not common until the Late Period (664-332 BC).

Mummy, roughly translate to “embalmed corpse”, as well as an embalming substance. The term is now applied to all human and animal remains, which retain their soft tissue.

Egyptian Mummification

The earliest mummies from prehistoric times probably were accidental. By chance, dry sand and air (since Egypt has almost no measurable rainfall) preserved some bodies buried in shallow pits dug into the sand. About 2600 B.C., during the Fourth and Fifth Dynasties, Egyptians probably began to mummify the dead intentionally. The practice continued and developed for well over 2,000 years, into the Roman Period (ca. 30 B.C.– C.E. 364).

Mummification varied, depending on the price paid for it. The best prepared and preserved mummies are from the Eighteenth through the Twentieth Dynasties of the New Kingdom (ca. 1570–1075 B.C.) and include those of Tutankhamen and other well-known pharaohs.

MYTH: Osiris the Immortal

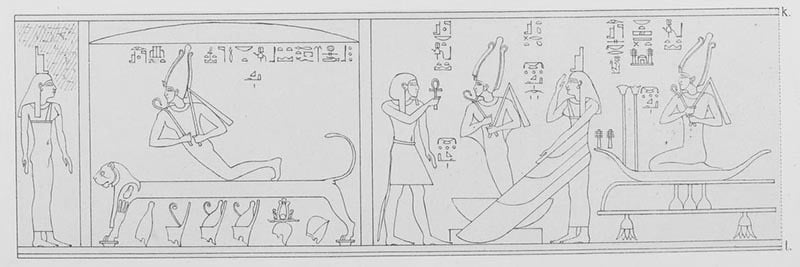

Mortuary rituals around death, dying, and mummification and their symbols were largely derived from the cult of Osiris.

Osiris and his sister-wife Isis were the mythical first rulers of Egypt, given the land shortly after the creation of the world. They ruled over a kingdom of peace and tranquility, teaching the people the arts of agriculture, civilization, and granting men and women equal rights to live together in balance and harmony.

Osiris’ brother, Set, grew jealous of his brother’s power and success, and so murdered him; first by sealing him in a coffin and sending him down the Nile River and then by hacking his body into pieces and scattering them across Egypt. Isis retrieved Osiris parts, reassembled him, and then with the help of her sister Nephthys, brought him back to life.

Osiris was incomplete, however – he was missing his penis, which had been eaten by a fish – and so could no longer rule on earth. He descended to the underworld where he became Lord of the Dead.

Prior to his departure, though, Isis had mated with him in the form of a kite and bore him a son, Horus, who would grow up to avenge his father, reclaim the kingdom, and again establish order and balance in the land.

CC -BY-SA 3.0., edited.

This myth infused the culture and assimilated earlier gods and myths to create a central belief in a life after death and the possibility of resurrection of the dead.

Osiris was often depicted as a mummified ruler and regularly represented with green or black skin symbolizing both death and resurrection. The cult of Osiris offered salvation, resurrection, and eternal bliss for his people.

Eternal life was only possible, though, if one’s body remained intact.

A people’s name, their identity, represented their immortal soul, and this identity was linked to one’s physical form.

The embalming Process

Burial practice and mortuary rituals in ancient Egypt were taken seriously because of the belief that death was not the end of life. The individual who had died could still see and hear, and if wronged, would be given leave by the gods for revenge.

The complete mummification procedure took 70 days and incorporated several stages, all of which had important ritual significance, as well as having practical implications for the handling of dead bodies.

The main elements of the process are detailed below:

Cleansing

The deceased person’s body was washed and purified. This took place as soon as possible after death as decomposition would begin immediately in the hot climate of Egypt.

Organs Removed

First the brain (excerebration) was removed using a metal rod with a hook on the end that perforated the ethmoid bone in the nasal cavity. The brain was liquified and drained out of the skull through the nose. Breaking the nose was not the preferred method, because it could disfigure the face of the deceased and the primary goal of mummification was to keep the body intact and preserved as life-like as possible.

Organs were then removed from the body cavity (evisceration). The cavity is then thoroughly cleaned and washed out, firstly with palm wine and again with an infusion of ground spices.

The most important organs to the ancient Egyptians were the lungs, liver, stomach and intestines, which were preserved, wrapped and placed in individual vessels called canopic jars. It was important that the heart remained in the body as the Egyptians believed it to be the centre of an individual’s intellect, emotion and memory.

Dehydration

The body was dried internally and externally using a sodium salt mixture called natron. The body was covered with a large quantity of natron. After 35 to 40 days, the natron was removed leaving the body desiccated and shrunken but maintaining soft tissue and skin.

Anointing

The body was then anointed with coniferous oils and perfumes, which served both a ritualistic function to purify and bestow divine status on the deceased as well as a practical function to make the tough, dried out skin more supple. The skull and body cavities were then filled with materials such as pure myrrh, cassia, and every other aromatic substance, excepting frankincense, mud and linen.

Wrapping

The body was wrapped from head to foot in linen cut into strips and smeared on the underside with gum, which is commonly used by the Egyptians instead of glue.

The bandages assisted with maintaining the body’s integrity and, like the other stages of mummification, was also of important ritual significance acting like a cocoon from which the deceased would emerge, reborn in the afterlife.

Burial

To complete the mummy for burial it could be encased in a coffin or adorned by a mask, the most famous example of which is the golden mask of Tutankhamun. The earliest coffins date to around 3000 BC; they were simple boxes made of reeds, wood or clay and the body within was placed in a contracted or foetal position. During the Old Kingdom (2686-2181 BC), the preparation of the deceased required that the body was fully extended and therefore coffins became full length.

By the Middle Kingdom (2125-1650 BC), these rectangular coffins developed into the mummiform (anthropoid or human-shaped) coffins that dominate museum collections today. Over the thousands of years that ancient Egyptian coffins were in use, their shape and design evolved, however, their essential function remained the same, to protect the deceased.

This embalming process was followed with animals as well as humans. Egyptians regularly mummified their pet cats, dogs, gazelles, fish, birds, baboons, and also the Apis bull, considered an incarnation of the divine.

Although the above processes are the standard observed throughout most of Egypt’s history, there were deviations in some eras. Egyptologist, Margaret Bunson notes:

Each period of ancient Egypt witnessed an alteration in the various organs preserved. The heart, for example, was preserved in some eras, and during the Ramessid dynasties the genitals were surgically removed and placed in a special casket in the shape of the god Osiris. This was performed, perhaps, in commemoration of the god’s loss of his own genitals or as a mystical ceremony.

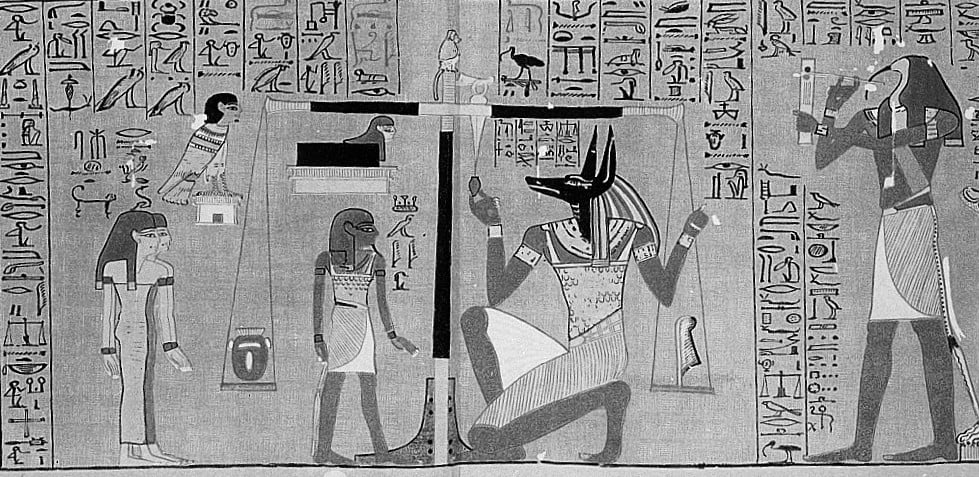

The heart of the matter

Only the heart was left inside the body as it was thought to contain part of the soul. Thought to be the seat of the person’s identity and character.

The heart played an important role at the time of judgment of the deceased in front of the God of the Afterlife, Osiris.

Anubis, the jackal headed god is shown conducting the ceremony during which the heart is weighed against a feather of truth, symbol of righteous truth. Thoth, the ibis-headed scribe, records the result on a tablet.

If the heart was heavier than the feather, it would prove that the deceased had not lived a virtuous life while on earth and therefore, would not be permitted to enter the afterlife to take their place with Osiris.

Medias creative curses

There were all sorts of versions of the specific “curse” to which Carnarvon’s death could be attributed, but most tried to relate it to an inscription of warning in the tomb. Some of the reporters had the aid of disgruntled Egyptologists, who had not only been denied access to the tomb, but also any information about it.

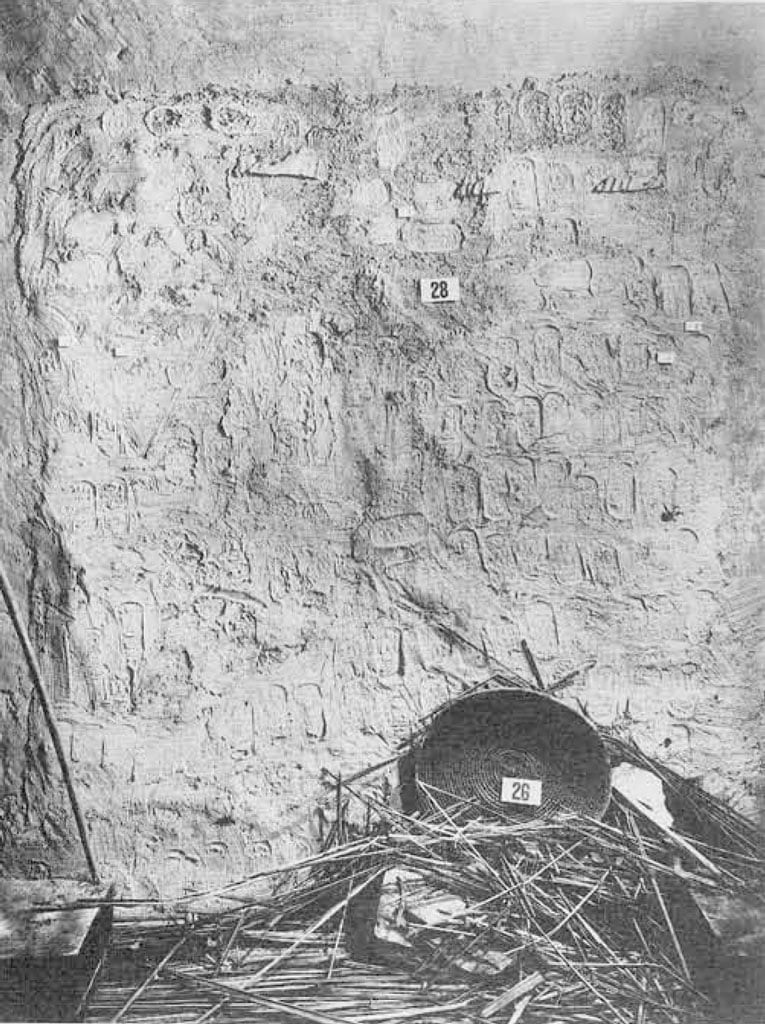

Based solely on published photographs. In this manner, many inscriptions could be construed as curses by the public, especially after a “re-invention” by the press. For example, an innocuous text inscribed on mud plaster before the Anubis shrine in the Treasury stated:

“I am the one who prevents the sand from blocking the secret chamber,”

In the newspaper, it metamorphosed into:

“I will kill all of those who cross this threshold into the sacred precincts of the royal king who lives forever.”

Such misrepresentation proliferated, and soon curses were being found in several of the inscriptions. Since few people could read the texts and thereby check the original, the reporters were inventive. They did publish a photograph of the large golden shrine in the Burial Chamber, together with a “translation” of the accompanying inscription:

“They who enter this sacred tomb shall swift be visited by wings of death.”

The carved figure of a winged goddess that accompanied the shrine would no doubt reinforce the “translated” threat. In reality, the texts on this shrine come from The Book of the Dead—a collection of spells intended to ensure eternal life, not to shorten it!

Real Egyptian Curses

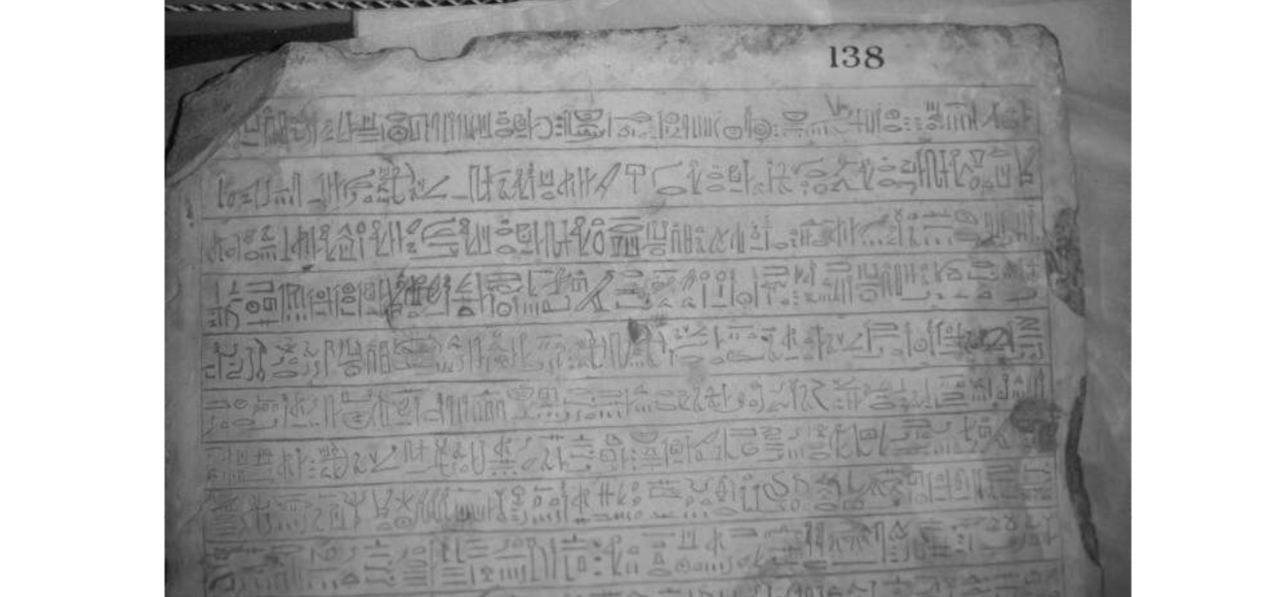

Silverman David collected some Egyptian curses:

Ancient Egyptians did in fact use curses couched in the form of threats, and they occur mainly on the monuments of private citizens rather than on those of royalty.

In fact, most of the curses come from inscriptions on the walls of private tombs of the Old Kingdom, during a time when the royal tombs (pyramids) were decorated with a set of spells called Pyramid Texts that were meant as aids, advice, and directions for the king.

Because of their size, prominence, and the existence of a large group of priests attached to the funerary complex, the royal funerary monuments obviously had the protection they needed.

Royal curses, when they do occur, are directed more toward this life than the next. There is an address at Deir el Bahri by Thutmose I to the court of his daughter, the reigning pharaoh Hatshepsut:

“He who will adore her, he will live; he who will speak evil in a curse against her majesty, he will die”

Sethe 1906.

Somewhat distinct are the “execration texts” that occur on pottery bowls and figurines from the end of the 12th-13th Dynasty. These are curses against foreign states or peoples that might act or had already acted against Egypt. At appropriate times, the objects with their curses were ritually smashed.

Amenhotep, son of Hapu, was a remarkable figure from the 18th Dynasty, who was later deified (in the 21st Dynasty). A mortuary temple which was built in his honor was protected by a rather lengthy and detailed curse:

“As for [anyone] who will come after me and who will find the foundation of the funerary tomb in destruction…

as for anyone who will take the personnel from among my people…

as for all others who will turn them astray…

I will not allow them to perform their scribal function…

I will put them in the furnace of the king…

His uraeus will vomit flame upon the top of their heads, demolishing their flesh and devouring their bones.

hey will become Apophis [a divine serpent who is vanquished] on the morning of the day of the year.

They will capsize in the sea which will devour their bodies.

They will not receive honors received by virtuous people. They will not be able to swallow offerings of the dead.

One will not pour for them water in libation…

Their sons will not occupy their places, their women will be violated before their eyes.

Their great ones will be so lost in their houses that they will be upon the floor…

They will not understand the words of the king at the time when he is in joy.

They will be doomed to the knife on the day of massacre…

Their bodies will decay because they will starve and will not have sustenance and their bones will perish”

~British Museum Stele 138; Varille 1968.

Important decrees could also be protected by threats, especially in regard to specific individuals already proclaimed guilty, as this indictment shows:

“As to any king and powerful person who will forgive him, he will not receive the white crown, he will not raise up the red crown, he will not dwell upon the throne of Horus of the living. As for any commander or mayor who will petition my lord to pardon him, his property and his fields will be put as offerings for my father Min of Coptos”

Sethe 1959:98

Egyptian curses are hardly a mystery, hardly an enigma. Their suggestive remarks and threats were meant to dissuade those who might act against them. The means by which this was accomplished was the written word, so important in all aspects of Egyptian culture. The curse would survive as long as the monument on which it was written.

“In a land where only about 5% of the population was literate it seems unlikely that those tempted to rob could actually read any warning.

Instead, it was widely accepted, that the dead had the power to interfere with the living.”

Tutankhamun, the superstar

Times have not changed, when the Director General of the Egyptian Antiquities Department, Dr Gamal Mehrez, died; he had been chronically ill, but his death was attributed to the movement of King Tut’s treasures for an exhibition in England.

Even Tutankhamun himself might have been pleased with the discovery of his tomb. The memory of his very existence was removed, so during those three millennia of solitude, no one pronounced his name. For the ancient Egyptians,

“the renewal of life for the dead is leaving his name on earth behind him.”

Insinger Papyrus, dating from the Greco-Roman era, but most likely based on ancient wisdom.

The ancient Egyptians believed that their souls were kept alive when their name was remembered, and this has been ensured with the curse.

The Grand Egyptian Museum (المتحف المصرى الكبير al-Matḥaf al-Maṣriyy al-Kabīr), also known as the Giza Museum, is an archaeological museum in Giza, Egypt. It will house artifacts of Ancient Egypt and is set to be the largest archaeological museum in the world.

The main attraction will be the exhibition of the full tomb collection of King Tutankhamun. The collection includes about 5,000 items in total and will be relocated from the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

We will see if a curse will struck… The power of superstition is great indeed. Like all good curse theories, natural death, accidents and sheer bad luck have been compressed into a single sinister hypothesis and with all this doom and gloom, there is only one piece of great news. The museum is expecting an increase in curious travelers.

The result of a deadly ancient curse, or circumstantial coincidences? That is for you to decide…

Learn about another mummy’s curse: The curse of the Iceman- Ötzi.

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun’s Family, www.jamanetwork.com

- Bunson, M. The Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Gramercy Books, 1991.

- gazette-eu-west2.azureedge.net/media/a-collection-of-howard-carter-letters-sold-for-5-200

- Joyce Tyldesley Dr. Tutankhamen’s Curse: The developing History of an Egyptian king. University of Manchester. www.egyptologyonline.ls.manchester.ac.uk

- Kemp

- Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun’s Family, www.jamanetwork.com

- Bunson, M. The Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Gramercy Books, 1991.

- gazette-eu-west2.azureedge.net/media/a-collection-of-howard-carter-letters-sold-for-5-200

- Joyce Tyldesley Dr. Tutankhamen’s Curse: The developing History of an Egyptian king. University of Manchester. www.egyptologyonline.ls.manchester.ac.uk

- Kemp, Barry and Albert Zink. “Life in Ancient Egypt: Akhentanen, the Amarna Period, and Tutankhamun.” In: “Sickness, Hunger, War, and Religion: Multidisciplinary Perspectives,” edited by Michaela Harbeck, Kristin von Heyking, and Heiner Schwarzberg, RCC Perspectives 2012.

- Schiød Sofie. www.humanities.ku.dk

- Sethe Kurt. Urkunden der 18. Dynastie. Urkunden des agyptischen Altertums IV. 1906.

- Silverman David. The Curse of the Curse of the Pharaohs. Expedition Magazine 29.2,1987. www.penn.museum

- The Egyptian Museum and the Arab Spring. The Looting of the Egyptian Museum

- Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation. The Howard Carter Archives. Photographs by Harry Burton The Griffith Institute. www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/gal

- Virtual Tour through the Tutankhamun Collection at the Egyptian Museum

- www.af.wikipedia.org/Toetankamen

- www.ancientegyptonline.co.uk/tutcurse

- www.bbc.co.uk/lord_carnarvon_tutankhamun_newbury_feature

- www.blog.griffith.ox.ac.uk/my-dear-gardiner

- www.britannica.com/Tutankhamun

- www.egymonuments.gov.eg/egyptian-museum

- www.en.wikipedia.org/Tutankhamun

- www.jamanetwork.com/joc

- www.livrepository.liverpool.ac.uk/ColledgeSar_Sep

- www.m.historyembalmed.org/curse-of-king-tut

- www.penn.museum/the-curse-of-the-curse-of-the-pharaohs

- www.perseus.tufts.edu/Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01,

- www.resources.metmuseum.org/Tutankhamuns_Tomb_The_Thrill_of_Discovery

- www.sydney.edu.au/mummification

- www.traffickingculture.org/egyptian-museum-cairo-thefts-and-recoveries-in

- www.worldhistory.org/cultural–theological-background-of-mummification

- www.worldhistory.org/herodotus-on-burial-in-egypt

- www.worldhistory.org/mummification-in-ancient-egypt

- www.worldhistory.org/the-mummys-curse-tutankhamuns-tomb–the-modern-day

- , Barry and Albert Zink. “Life in Ancient Egypt: Akhentanen, the Amarna Period, and Tutankhamun.” In: “Sickness, Hunger, War, and Religion: Multidisciplinary Perspectives,” edited by Michaela Harbeck, Kristin von Heyking, and Heiner Schwarzberg, RCC Perspectives 2012.

- Schiød Sofie. www.humanities.ku.dk

- Sethe Kurt. Urkunden der 18. Dynastie. Urkunden des agyptischen Altertums IV. 1906.

- Silverman David. The Curse of the Curse of the Pharaohs. Expedition Magazine 29.2,1987. www.penn.museum

- The Egyptian Museum and the Arab Spring. The Looting of the Egyptian Museum

- Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation. The Howard Carter Archives. Photographs by Harry Burton The Griffith Institute. www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/gal

- Virtual Tour through the Tutankhamun Collection at the Egyptian Museum

- www.af.wikipedia.org/Toetankamen

- www.ancientegyptonline.co.uk/tutcurse

- www.bbc.co.uk/lord_carnarvon_tutankhamun_newbury_feature

- www.blog.griffith.ox.ac.uk/my-dear-gardiner

- www.britannica.com/Tutankhamun

- www.egymonuments.gov.eg/egyptian-museum

- www.en.wikipedia.org/Tutankhamun

- www.jamanetwork.com/joc

- www.livrepository.liverpool.ac.uk/ColledgeSar_Sep

- www.m.historyembalmed.org/curse-of-king-tut

- www.penn.museum/the-curse-of-the-curse-of-the-pharaohs

- www.perseus.tufts.edu/Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01,

- www.resources.metmuseum.org/Tutankhamuns_Tomb_The_Thrill_of_Discovery

- www.sydney.edu.au/mummification

- www.traffickingculture.org/egyptian-museum-cairo-thefts-and-recoveries-in

- www.worldhistory.org/cultural–theological-background-of-mummification

- www.worldhistory.org/herodotus-on-burial-in-egypt

- www.worldhistory.org/mummification-in-ancient-egypt

- www.worldhistory.org/the-mummys-curse-tutankhamuns-tomb–the-modern-day

- stry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun’s Family, www.jamanetwork.com

- Bunson, M. The Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Gramercy Books, 1991.

- gazette-eu-west2.azureedge.net/media/a-collection-of-howard-carter-letters-sold-for-5-200

- Joyce Tyldesley Dr. Tutankhamen’s Curse: The developing History of an Egyptian king. University of Manchester. www.egyptologyonline.ls.manchester.ac.uk

- Kemp, Barry and Albert Zink. “Life in Ancient Egypt: Akhentanen, the Amarna Period, and Tutankhamun.” In: “Sickness, Hunger, War, and Religion: Multidisciplinary Perspectives,” edited by Michaela Harbeck, Kristin von Heyking, and Heiner Schwarzberg, RCC Perspectives 2012.

- Schiød Sofie. www.humanities.ku.dk

- Sethe Kurt. Urkunden der 18. Dynastie. Urkunden des agyptischen Altertums IV. 1906.

- Silverman David. The Curse of the Curse of the Pharaohs. Expedition Magazine 29.2,1987. www.penn.museum

- The Egyptian Museum and the Arab Spring. The Looting of the Egyptian Museum

- Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation. The Howard Carter Archives. Photographs by Harry Burton The Griffith Institute. www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/gal

- Virtual Tour through the Tutankhamun Collection at the Egyptian Museum

- www.af.wikipedia.org/Toetankamen

- www.ancientegyptonline.co.uk/tutcurse

- www.bbc.co.uk/lord_carnarvon_tutankhamun_newbury_feature

- www.blog.griffith.ox.ac.uk/my-dear-gardiner

- www.britannica.com/Tutankhamun

- www.egymonuments.gov.eg/egyptian-museum

- www.en.wikipedia.org/Tutankhamun

- www.jamanetwork.com/joc

- www.livrepository.liverpool.ac.uk/ColledgeSar_Sep

- www.m.historyembalmed.org/curse-of-king-tut

- www.penn.museum/the-curse-of-the-curse-of-the-pharaohs

- www.perseus.tufts.edu/Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01,

- www.resources.metmuseum.org/Tutankhamuns_Tomb_The_Thrill_of_Discovery

- www.sydney.edu.au/mummification

- www.traffickingculture.org/egyptian-museum-cairo-thefts-and-recoveries-in

- www.worldhistory.org/cultural–theological-background-of-mummification

- www.worldhistory.org/herodotus-on-burial-in-egypt

- www.worldhistory.org/mummification-in-ancient-egypt

- www.worldhistory.org/the-mummys-curse-tutankhamuns-tomb–the-modern-day