The Iceman – Ötzi, the Glacier Mummy is forever sleeping in a big refrigerator. The frozen mummy is stored in a specially devised cold cell, chilled to a glacial minus 6.5 degrees Celsius, or 20.3 degrees Fahrenheit, and 99% humidity.

We can see him through a small window in the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano/Bozen. Discover the curse of the Iceman – Ötzi, his tattoos and ethnomedicne from the Copper Age.

In this Article

The exhibition covers the circumstances of Ötzi’s accidental discovery on 19 September 1991, the international media response, the original findings, daily life in the Copper Age and multidisciplinary research carried out on the archaeological find of the century.

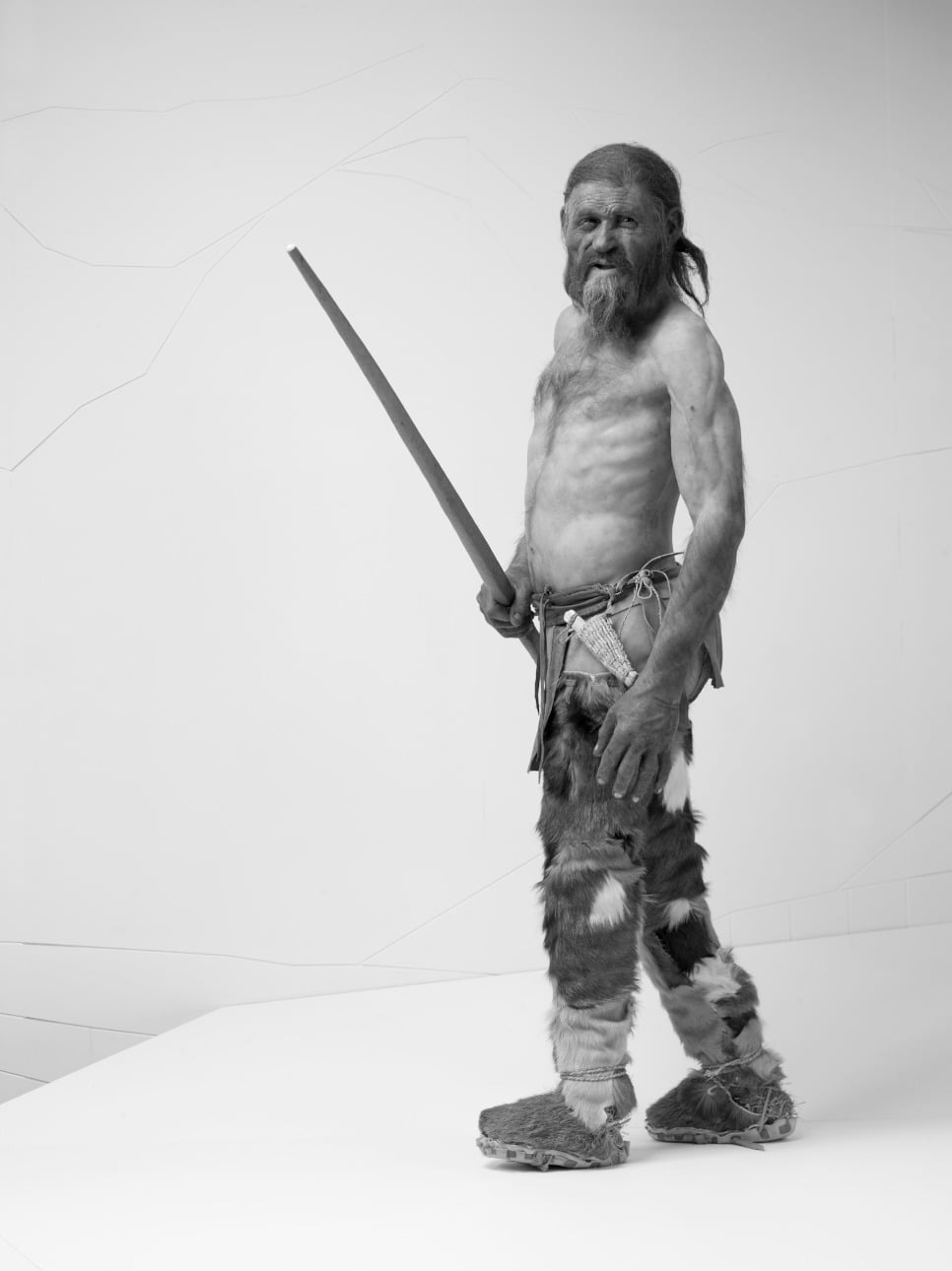

A highlight of the exhibition is the life-like reconstruction of the Iceman, which vividly portrays how the mummified body may have looked during his lifetime.

Frozen in Ice: Ötzi

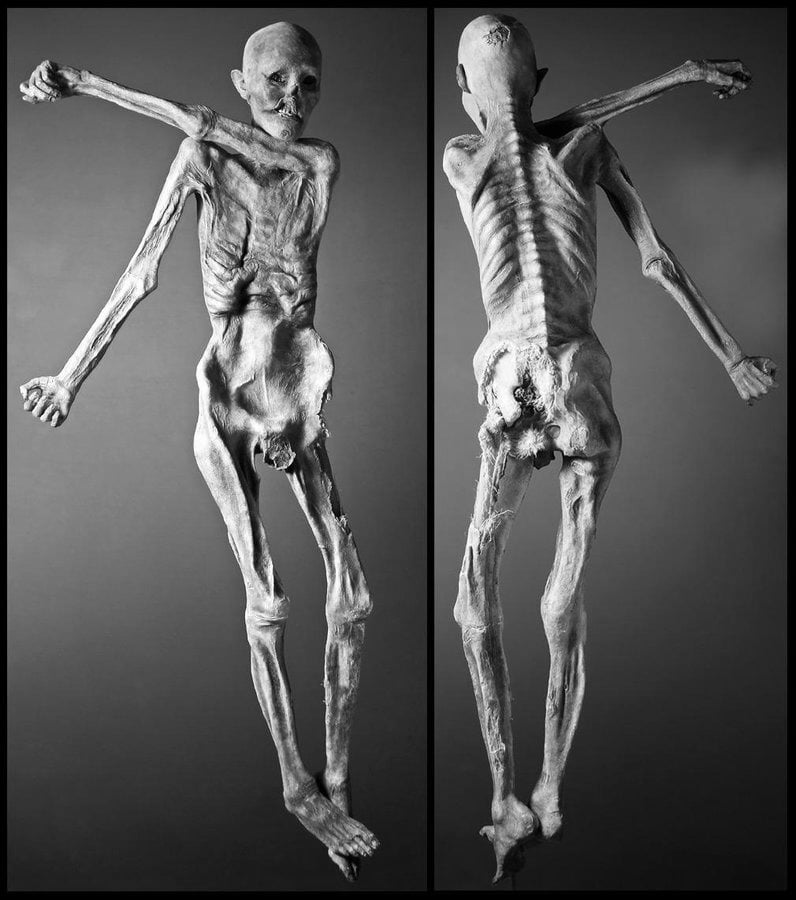

Ötzi lived about 5300 years ago and his body was extraordinarily well preserved, because after death it was dried quickly by the alpine winds and then froze, encased in the perennial ice.

Ötzi — a few key data:

Age: Examination of the osteons (functional units of bone) in Ötzi’s femur (thigh bone) put his likely age to be around 45. This was a good age considering the short life expectancy in 3300 BC

Height: The mummy is 1.54 m in length. In life, he must have been about 5 feet, 3 inches (1.60 m) tall. His shoe size would have been today’s equivalent of a continental 38 – the average for the population at the time.

Weight: Ötzi weighs approx. 29 pounds (13.15 kg). In life, he would have weighed about 110 pounds (49.9 kg). Since there is little subcutaneous fat on the body, he must have cut quite a wiry, sporty figure.

Hair: A few clumps of hair were found around the body, indicating that Ötzi had dark, medium-long hair, which he wore loose. Traces of arsenic were found in his hair, leading to the conclusion that he was sometimes present where metal ores were being smelted.

Nails: Ötzi’s fingernails and toenails fell off as he decomposed. During excavations, one fingernail and two toenails were retrieved. Horizontal grooves, or Beau’s lines, were observed on the fingernail — an indication of great physical stress.

Parasites: Two human fleas were found in his clothing, but no infestation on him. Scientists also found the oldest evidence of borreliosis, or Lyme Disease, an infectious disease transmitted by ticks, in Ötzi’s DNA. Deer flies (Lipoptena cervi) were found in the clothes of Ötzi. The deer fly is a blood-sucking parasite that mainly affects wild animals, but occasionally also pets and humans.

DNA: Ötzi’s genome has been almost completely decoded. His haplogroup (genetic population group) is rare in modern-day Europe and is found almost exclusively among inhabitants of the islands of Sardinia and Corsica, who were isolated for long periods. The Iceman was genetically predisposed to cardiovascular disease, which manifested itself in the form of arteriosclerosis. He was probably lactose intolerant, and his blood group was 0 positive.

Last meal: Ötzi’s very last meal just shortly before his death, consisted of dried, fatty ibex and deer meat (probably a kind of dried meat), along with bread made from einkorn wheat and a bit of bracken fern. This meal is preserved as about 300 g in Ötzi’s stomach. A single small piece of seed from the goosefoot herb was also found in his intestines.

Etymology: The glacier mummy, Ötzi, the Iceman, Similaun Man…

“Ötzi the Iceman” was originally named in German, “der Mann aus dem Eis” as Ötzi’s official name, which is “the Man from the Ice” in English. In the German-speaking countries, the name “Ötzi” is preferred, as it is used like an informal first name. The name refers to the discovery site in the Ötztal Valley Alps and is a short form for “Ötztaler Yeti”.

The mummy was dubbed Ötzi by the Austrian journalist Karl Wendl, who was looking for a catchy name. In the English-speaking world, “Ötzi” is being used more often by those that know of him, but can be hard to pronounce, so he is usually referred to as “Ötzi the Iceman” or just “The Iceman”.

Following reports of the find by the international media, various names were coined for the mummy. Over 500 nicknames were mooted in the first few weeks. Such as: Eismann, Homo tyrolensis, Frozen Fritz and Hibernatus (French).

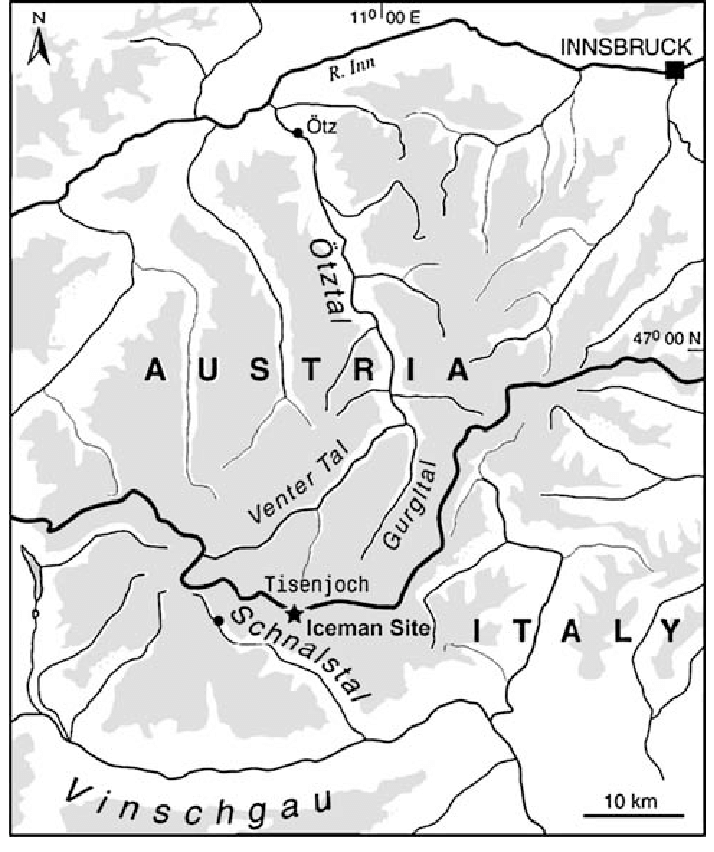

Man from the Tisenjoch (mountain) and Schnalsi (from Schnals valley), as well as, Similaun Man and the Man from Hauslabjoch derived from the locations – near Similaun mountain and Hauslabjoch, at the border between Austria and Italy where the glacier mummy was discovered.

The term “Ötzi” has become internationally known. It is commonly equated with the characteristics “coming from the ice/ the Alps”, “very old”, “particularly courageous, persevering”, “persistent”, “sporty”, “cool”, or “environmentally friendly”.

For this reason, it has been and is used time and time again to designate products, which (should) remember some or all of these characteristics.

Examples include: Ötzi sportswear, Ötzi eco-shoes, Ötzi creams, Ötzi mountain bike by Bianchi, Ötzi Vitara (an off-road car of the Suzuki brand); Ferrero: the Ötzi’s sweets, a marathon in South Tyrol, Ötzi shoelaces and other outdoor products.

Ötzi is used also for a new homeopathy according to Körbler, called Ötzi therapy; car tuning, shop names, a local supplier of electric energy, transport of refrigerators and the Ötzi finder, software by iPhone for finding avalanche victims, and much more.

History: Ötzi the Iceman’s discovery

Due to the warm summer of 1991, the snout of the Val Senales glacier (south Tyrol, north Italy) 10,530 feet (ca. 3,210 m), above sea level, had melted considerably, and this is why his upper body was clearly visible protruding from the ice and melt water.

The corpse lay in a gully on Tisenjoch/Giogo di Tisa, and was thus protected from the destructive forces of the moving glacier. The rocky gully was probably free of ice when Ötzi died there.

How? Extensive analysis of Ötzi’s body, alongside X-rays and a CT scan, showed an arrowhead had been lodged in his shoulder when he died. Subsequently, he has been covered with snow and the glacier ice. Today, a large stone pyramid stands near the discovery site to commemorate this fortuitous archaeological find.

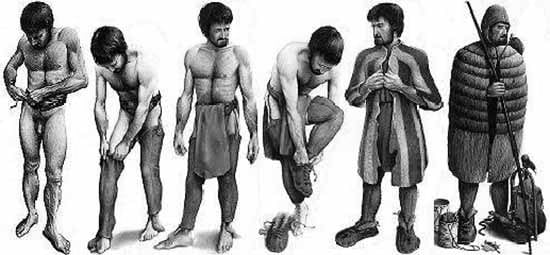

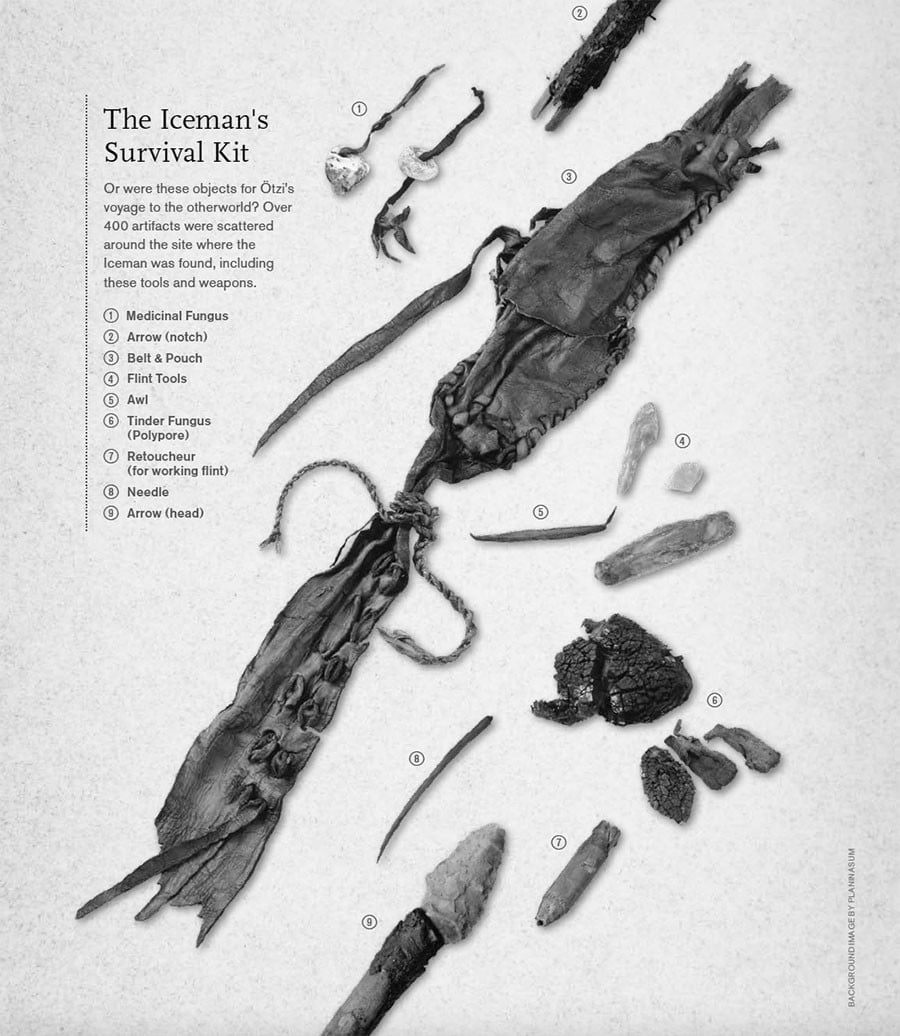

Miraculously, ice had preserved not only the body, but the equipment the Iceman had with him when he died – ordinary possessions rendered priceless by time:

a bead with rawhide strings, two dried-out mushrooms on leather straps, finely stitched clothing made from animal skins, straw-lined leather shoes, an impermeable cloak made of woven grass, a bear skin cap, a pack that still had some food in it (dried deer meat and a prune), a finely worked birch bark pouch, a wooden bow, a leather quiver with a number of arrows (some unfinished), a flint-bladed knife, and a wood-handled copper-bladed axe.

Hunting may have played an important role in Ötzi’s life. The fur of wild animals (bear, stag, roe deer) were used in making his clothing, the antler tips in his quiver came from a red deer and he ate wild animal meat (red deer, ibex).

In addition, parts of his equipment (bows, nets, bird/game carrier) can also be used for hunting. The Iceman also gathered provisions that grew in the wild. But he belonged also to a sedentary society that practiced agriculture and raised livestock. This is suggested by the grain residues (barley and einkorn wheat) found with Ötzi. In addition, the Iceman was wearing leather and fur garments from domesticated animals (goat, sheep, and cow).

Ötzi’s discovery ranks as one of the greatest archaeological finds of the 20th century. His clothing and equipment is all the more important, because they were not the customary funerary offerings, well known from the archaeological excavation of thousands of tombs, but rather the objects the man used in his daily life.

Ötzi lived in the middle of the Copper Age. It is a time between the Neolithic and the Bronze Age. At that time, the techniques for metal extraction and processing were developed. Despite the discovery of copper, stone tools (stone palstaves or axes) are still used, because not everyone had access to copper, and they are functional and can be produced by most people. For this reason, the term Chalcolithic is also used for this time. In Central Europe it lasts from about 4300-2200 BC.

The study of the mummy has resulted in several important and in part unexpected archaeological and medical discoveries. But so did the murmurings about a curse, built around the theory that the Iceman was angry at being disturbed after 53 centuries.

MODERN MYTH: THE CURSE OF ÖTZI – The Iceman

Ötzi was discovered high in the Italian alps near the Austrian border, and reports and pictures of the well-preserved Stone Age man sparked worldwide interest.

Mysterious ancient curses are by no means confined to the land of the pyramids and King Tut’s tomb. Indeed, one of the recent such alleged curses can be linked to an enigmatic individual frozen in ice for millennia in the Alps, who has stirred up not only academic mysteries, but also mysteries of the unknown…

Is the Iceman cursed

High in a remote area of the Ötztal Alps in northern Italy, he was shot in the back with an arrow.

Struck in a main artery, he likely bled to death within minutes and was near-perfectly preserved in the ice.

Perhaps he is still making his mark on the lives of those disturbing his rest…

We all know that every ancient mummy is cursed, so of course the Iceman has his own story. The alleged curse revolved around the deaths of several people involved with the discovery, recovery and subsequent analysis of Ötzi’s body.

The head of the forensic team examining Ötzi, Rainer Henn, 64, a scientist from Innsbruck University, was the man to place Ötzi’s frozen remains into a body bag. He tragically died in a fatal car crash while travelling to a lecture about the iceman, just a year after Ötzi was discovered.

The mountaineer who led Henn to the Iceman’s body, Kurt Fritz, 52, died in an avalanche in 1993, the only one of his party to be hit.

Helmut Simon, 67, disappeared in the Alps in October 2004. He and his wife had discovered Ötzi 13 years prior. It took searchers eight days to find his body due to snowy conditions.

Within an hour of Simon’s funeral, the head of the mountain rescue team that was assigned to find him, Dieter Warnecke, 45, died of a heart attack.

The man who filmed Ötzi’s removal from his icy mountain grave, celebrated Austrian journalist Rainer Hoelzl, 47, died of a brain tumor not long after finishing the film. The Independent reported in 2005, not long after he died, that he was aware of the alleged curse, and said:

“I think it’s a load of rubbish.

“It is all a media hype. The next thing you will be saying, I will be next.”

The seventh such person to die within a year is US-born molecular archaeologist Tom Loy, he suffered from a blood-related condition for about 12 years, his condition was diagnosed shortly after he became involved with the Iceman. He was found dead at his home in Brisbane in November 2005. An autopsy concluded he had died of natural causes, or an accident, or both.

Loy was renowned for discovering human blood on the Iceman’s clothing and weapons. His work debunked the theory that Ötzi, died alone in the mountains after a hunting accident. By revealing four different types of human blood on Ötzi’s clothing, he surmised that the Stone Age man was hunting with a companion when they got into a territorial skirmish.

Fatally wounded, Ötzi appears to have leaned against his companion for support. Weakened by blood loss, he put down his equipment neatly against a rock, lay down and expired.

Curse or coincidence?

People involved in the recovery of the mummy and the scientific investigation of the Iceman have died as a result of accidents or disease. The popular press has been quick to ascribe these deaths to the “curse of Ötzi”. However, hundreds of people have worked on the Iceman project, and many years have passed since the corpse was first discovered. It is therefore not remarkable that some of those people have since died.

This is the sort of curse that starts its life as speculation and then becomes an urban legend…

Could this whole “curse” simply be a journalist’s invention, sensationalism for article sales, much like the Curse of the Pharaoh Tutenkhamun?

Like all good curse theories, natural death, accidents and sheer bad luck have been compressed into a single sinister hypothesis and with all this doom and gloom, there is only one piece of great news. The museum in the Italian town of Bolzano specially constructed for the Iceman is expecting an increase in curious travelers.

The result of a deadly ancient curse, or circumstantial coincidences? That is for you to decide…

Copper Age Ethnomedicine: Ötzi’s tattoos

Show me a man with a tattoo and I’ll show you a man with an interesting past.

Jack London, 1883.

In ”The Man in the Ice,” published in 1994, Dr. Konrad Spindler, an archaeologist at the University of Innsbruck in Austria who led the early investigation of the mummy, noted the first evidence suggesting that the Iceman might have been carrying some natural medicines.

”All folk medicine has its origins in prehistory …

Over hundreds and thousands of years remedies were passed on from generation to generation.

The modern pharmaceutical industry has frequently analyzed the active constituents of traditional medicines and makes use of them to this day, where synthetic forms cannot be produced.

Seen in this light, the Iceman with his modest but no doubt effective traveling medicine kit, is not all that remote from ourselves.”

Dr. Spindler, (Konrad Spindler, head of the Iceman investigation team at Innsbruck University).

Tattoos – Adornment or therapy?

After years of work by an international team of scientists, a portrait of this mysterious time-traveler is finally emerging. Since Ötzi is a wet mummy and his tissue, bones and organs are well-preserved, numerous examinations have been carried out on him to learn more about his state of health when he was alive.

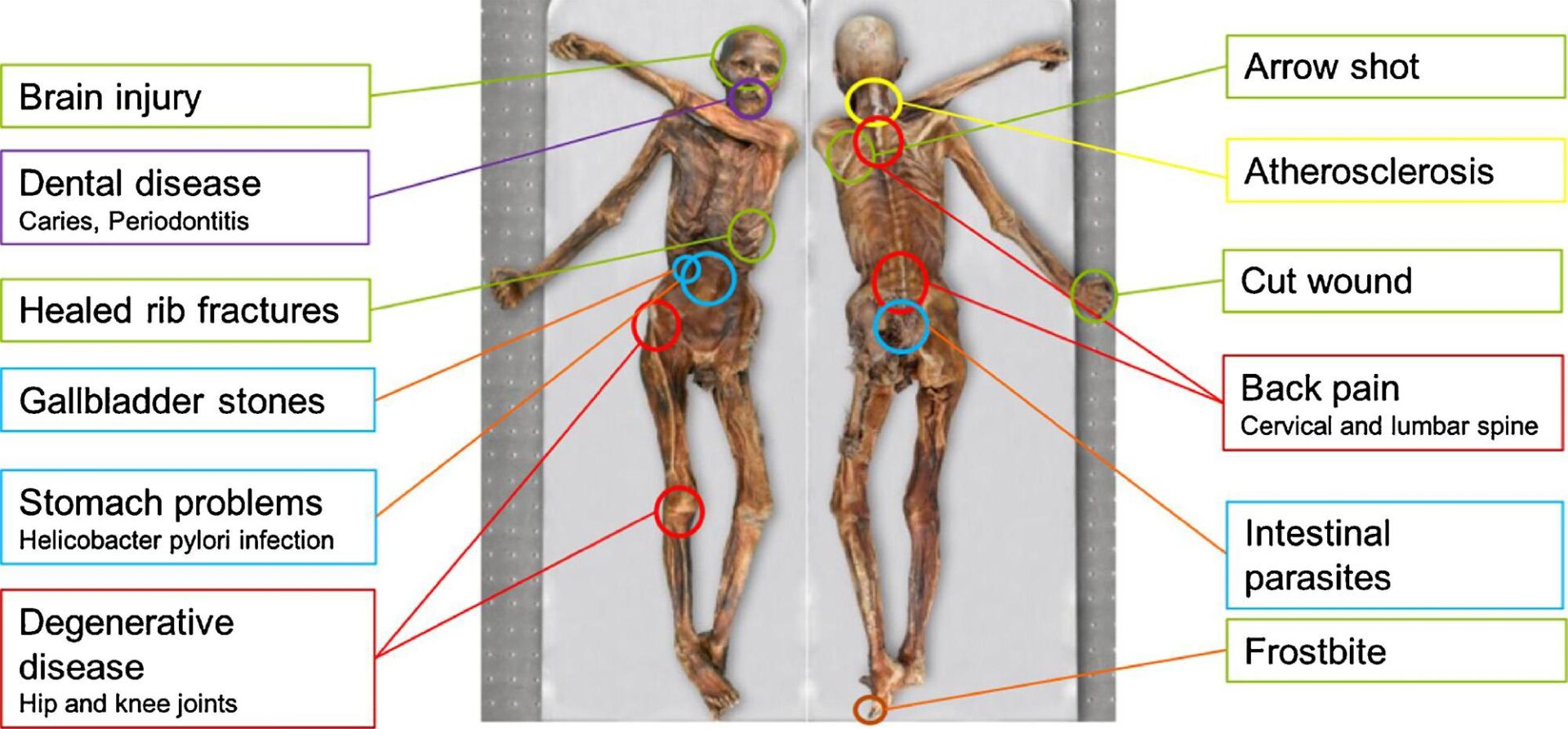

Ötzi was fit, but not completely healthy. His joints were worn out and his veins were calcified. He probably had stomach pain from worms in his intestines and gallstones. The teeth are heavily worn down and some are infested with tooth decay. On his left little toe there are still consequences of frostbite. What must have troubled him in the last days before his death is the deep cut wound on his right hand, which was only a few days old.

The Iceman’s body holds – strange markings on the skin – tattoos

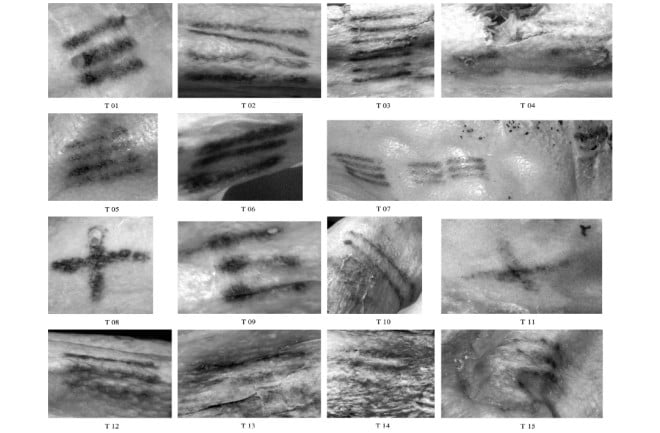

61 tattoos were found on Ötzi’s body,they are lines or crosses. Two tattoos are small crosses, they are on the right knee and on the left heel.

Unlike modern tattoos, they were not made with a needle; they were fine incisions; stuck or scratched with a bone needle or a flint blade into which pulverized charcoal was rubbed. The color of the vast majority of Ötzi’s tattoos is made from soot. Only the tattoo on his right leg had ash particles found between the soot residue. This may be due to the fact that the soot was taken from a different part of the fireplace for the remaining tattoos, or that he had the tattoo done at a different time.

Scientists are still puzzled about the significance of the tattoos. They were located in places that would have been covered by clothing most of the time, so they don’t seem to have been made for adornment. Today, it is assumed that the tattoos served therapeutic purposes.

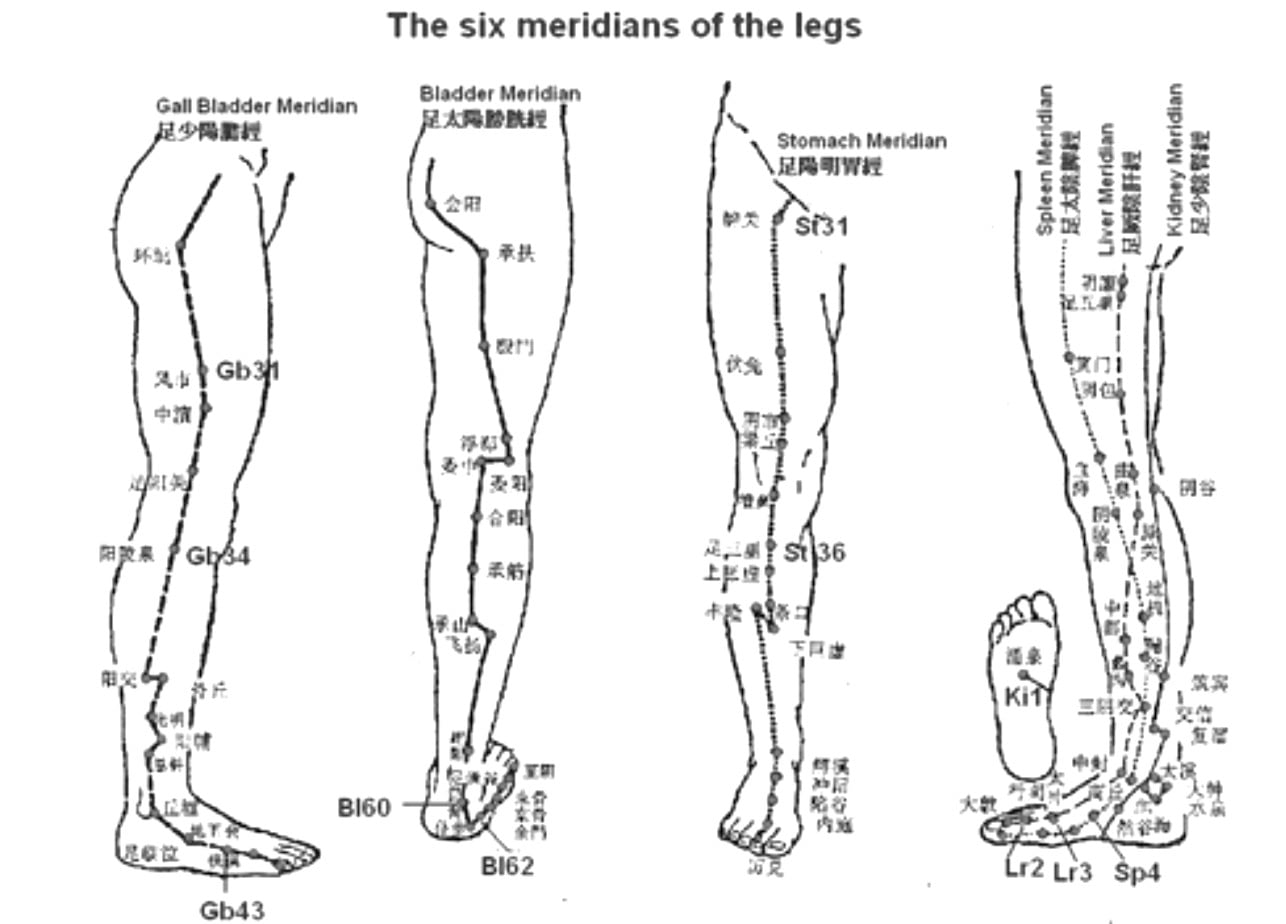

It is believed, that the tattoos were made in a bid to soothe pain. This theory is supported by the location of the tattoos on acupuncture lines that are still used today. 80% of the tattoo positions correspond to points employed to treat rheumatic illness, it seems very likely that these tattoo-punctures had the purpose of relieving the degenerative effects of Ötzi’s conditions.

Small linear incisions besmirched with bluish-black carbon pigments were placed at precise locations on the body corresponding to major joint articulations. Radio-graphic analyses of the Iceman’s corpse revealed considerable arthritis in many of the same regions (lower back or lumbar spine, hip joints, knee joints, and ankle joints) where the tattoos were applied.

It has been proposed that Ötzi’s indelible treatments were repeated over time, because many of the Iceman’s 5300-year-old tattoos are exceedingly dark, suggesting multiple applications to the same loci.

One of these tattooed regions (like the lumbar spine) must have been punctured by another individual, because the Iceman would not have been able to reach it with precision. The Iceman also possessed two lines of tattooing around one of his wrists.

Other researchers have added to the list of Ötzi’s indelible medical therapeutics. Dorfer indicated that markings on the mummy’s back and right leg were positioned on the gall bladder, spleen, liver, and stomach acupuncture meridians.

Meridians are specific pathways that connect the internal organs with points that are located either on the epidermis, often in close proximity to nerves and blood vessels. The meridians and points are utilized by acupuncturists today to treat abdominal disorders.

Moreover, as we have no other evidence for the practicing of tattooing in the alpine region or even in the Western culture of historic times, we are not able to draw any conclusions on the effectiveness and the possible success of this treatment. On the other hand, it has to be considered that the Iceman’s health problems most probably required a regular treatment and the possible application of acupuncture may have been effective.

Acupuncture is a method of treatment in traditional Chinese medicine. This assumes that invisible energy lines (meridians) run in the human body, in which the qi (life energy) flows.

A disturbance in this energy flow is blamed for illnesses. The treatment of meridians with fine needle stitches corrects the disorder.

Ötzi’s tattoos lie along these lines in places that are also used today for pain treatment by acupuncture.

If Ötzi’s tribe were practicing “Chinese medicine”, then according to the diffusion theory other shamanistic cultures must have done so, too.

Civilizations from East and West may have crossed paths, transacted business and traded cultural practices long before we can imagine. Or did different cultures have independently arrived at the same conclusions?

“At the time when Ötzi was around, I’m sure that many shamanistic cultures worldwide might have practiced it [Acupuncture], but only the Chinese formalized it and saved it into modern times.”

Dr. Moser Max (Professor of Physiology at the University of Medicine in Graz (Austria) and head of the Human Research Institute).

Medicinal tattooing

For more than five millennia, tattooing has been a permanent part of medicinal culture the world over. Far from being either an arcane or quotidian medical technique, tattooing worked to help negotiate humanity’s relationship with the body as it continually struggled with those physiological and spiritual processes that threatened to injure and destroy it.

Because corporeal marking allowed individuals to gain control over the boundaries and passages of their bodies, to which and from which sickness and health lowed, it was enmeshed in a therapeutic complex of personal power and magic illustrating communal and individual desires and fears.

Thus, medicinal tattooing provided the skin with a secondary covering that was fundamental in protecting it from the natural and supernatural elements of its surrounding environment, while also interactively shaping it by firmly anchoring local indigenous values on the epidermis for all to see.

The oldest tattooed human remains?

Until recently there was a discrepancy regarding the identity of the oldest tattooed human remains, with popular and scholarly sources alternately awarding the honor to the Tyrolean Iceman, or to a South American Chinchorro mummy.

Using infrared light Egyptologists have identified figurative tattoos on a handful of mummies spanning 3,000 years of Pharaonic Egypt, the oldest lived between 3351 and 3017 BC, and they are almost as old as Ötzi who is thought to have lived between 3370 and 3100 BC.

We can at least acknowledge that the tattooist of that time did put considerable effort into applying the 61 tattoos on his body and, irrespective of the efficacy of the treatment, provided care for the Iceman. In a wider sense, it also has implications for our understanding of the Iceman’s society.

If they had developed acupuncture, it must have been through a trial and error system; and they needed to have had the ability and motivation to learn and practice therapeutic skills.

In such a context, it is quite believable that other forms of treatment (plant, fungi, etc.) were known and practiced.

Ethnobotany: Ötzi’s plant medicine

Ethnobotany is concerned with how people use plants and fungi as food, medicine and in customs. By Ötzi, fungi, mosses, and bast cords were found, which researchers did not immediately understand what he might have used them for.

Therefore, they have looked around the world to learn whether they were or will be used by humans and for what purpose. It has been understood that the grass mat can also be used as rain protection, and that the bast cords can serve as bowstrings.

Several dried pieces of blackthorn (sloe) were found near Ötzi. One of them is exhibited in the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology.

We do not know whether the blackthorn came from Ötzi or was lost by another human or animal at the site. However, it is quite possible that the blackthorn comes from Ötzi’s provisions, because blackthorn was often found in settlements at the time and was a valuable food, as it contains sugar and vitamin C.

Copper Age Herbal Medicine

There are several more indications that the Iceman and his people used forms of treatment to deal with their health problems. These include the possible application of therapeutic tattoos, the oral intake of herbal medicine (fern bracken), wound dressings and food (bog mosses) and antibiotic active substances (birch polypore).

Liverwort (Anemone hepatica)

Among the plant medicines found with Ötzi was, liverwort (Anemone hepatica), found in his stomach, an antibacterial, anti fungal, anti tumor, anti cancer, and insecticidal, it can improve circulation and digestion, lower cholesterol, and heals wounds.

Bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum)

Various analyses revealed a consistently high abundance of pollen and spores from the bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum in the various parts of the mummy’s gut. This indicates a somewhat regular ingestion of bracken by the Iceman. Interestingly, bracken contains ptaquiloside (PT), a highly carcinogenic compound, in all parts of the plant, and has therefore been regarded as a toxic plant.

The toxic components can be removed, however, by submerging the fern in water or placing the plants under acidic or alkaline conditions for a few hours before eating.

The ingestion of ferns has been reported in China about 3000 years ago and ferns are still widely consumed today in that country as well as in other Asian countries. Some fern species, in particular of the genus Dryopteris, known as wood or male fern, have long been used for the expulsion of intestinal parasites, such as tapeworms.

The use of Pteridium aquilinum for the treatment of worm infections seems not to have been common in earlier times. However, it has been reported that in India and Pakistan infusion of rhizome and fronds of this plant are taken orally against worms and in the case of stomach cramps.

Given the potential medical applications of different types of brackens, coupled with the gastrointestinal issues Ötzi seems to have suffered from, it is possible that he carried Pteridium aquilinum in his equipment as a form of self-medication.

Neckera and Anomodon mosses

The presence of Neckera and Anomodon mosses in the Iceman’s gut could be most likely explained by the use of this particular moss as food wrapping, which is further evidenced by its continuous presence in different areas of the intestinal tract.

In contrast, it is very unlikely that the Hymenostylium moss was used for wrapping given the hard, limy encrustations associated with this moss. The only moss commonly known to have been for medical use are species of Sphagnum, which were widely used until far in the 20th century as wound dressings, due to the high degree of absorbency and the particular wound-healing properties of Sphagnum holocellulose.

It was shown that the Iceman had a deep cut on his right hand that, must have happened at least 2–3 days before his death. If he was aware of the useful properties of Sphagnum for external wound treatment, it is well possible that he gathered some of the bog moss to treat the stab wound at his right hand.

He could then have accidentally ingested some pieces of the moss as he ate his last meal.

Birch polypore (Piptoporus betulinus) a “medicinal mushroom”

The finding of two pieces of birch polypore, Piptoporus betulinus, fastened to a leather band among his equipment, could be regarded as another indication for treatment of the Iceman. The fungi contain agaricine acid, a pharmacologically active substance that has anti-inflammatory and antibiotic properties.

Although other usage of the polypore has been proposed, such as for spiritual purposes or as tinder, a potential medical application appears to be the most plausible explanation based on our current knowledge.

Other recent scientific findings revealed that the Iceman suffered from whipworms in his colon. The discovery of a large amount of charcoal in that organ probably demonstrated an attempt at curing the malady through an oral dose.

It remains possible that some or most of these supposed medical applications found on, or in, the Iceman can be attributed to other reasons, such as an unintentional swallowing of pollen or plant remains, or the use of the fungi in lighting a fire.

Note: This post does not contain medical advice. Please ask a health practitioner before trying therapeutic products new to you.

If you do wish to experiment, we suggest doing further research.

The curiosity and questions are endless…This is the sort of mummy curse that starts its life as speculation and then becomes an urban legend…

Could this whole “curse” simply be a journalist’s invention, – sensationalism for article sales, – much like the Curse of Pharaoh Tut?

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

If you visit Bozen/Bolzano do not miss the Dolomites and the Walterplatz with his Minnesinger Walter von der Vogelweide.

- Deter-Wolf Aaron, Robitaille Benoît, Krutak Lars, Galliot Sébastien. The world’s oldest tattoos. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 5. 2016.

- Dorfer L, Moser, Bahr, Spindler, A medical report from the stone age? Lancet. 1999.

- www.iceman.it/oetzi-curse.

- www.express.co.uk/archaeology-news-warning-ozti-iceman-ancient-body-curse-spt.

- www.iceman.it/database

- www.iceman.it/the-iceman

- www.jesstfang.com/ö|Ö|ä|Ä|ü|Ützi-the-iceman-tattoo-acupuncture-pt1.

- Krutak Lars. The Power to Cure: A Brief History of Therapeutic Tattooing. In, Tattoos and Body Modifications in Antiquity Proceedings of the sessions at the EAA annual meetings in The Hague and Oslo, 2010/11.

- Pabst Maria Anna, Letofsky-Papst Ilse, Moser Maximilian, Egarter-Vigl Eduard. The tattoos of the Tyrolean Iceman: a light microscopical, ultrastructural and element analytical study. Article in Journal of Archaeological Science. 2009.

- Zink Albert, Samadelli Marco, Gostner Paul, Piombino-Mascali Dario. Possible evidence for care and treatment in the Tyrolean Iceman. International Journal of Paleopathology 25. 2019.