Frankincense is the fragrant gum resin obtained from balsam trees (Boswellia), most commonly the tree resin is put on a heat source so that smoke is given off.

Due to its therapeutic properties, the oleo-gum resin of some Boswellia species has been used in many countries for the treatment of rheumatic and other inflammatory diseases. There is also clinical support for respiratory, immune, brain and head, digestion, blood sugar, athletic performance, and urinary health.

In this Article

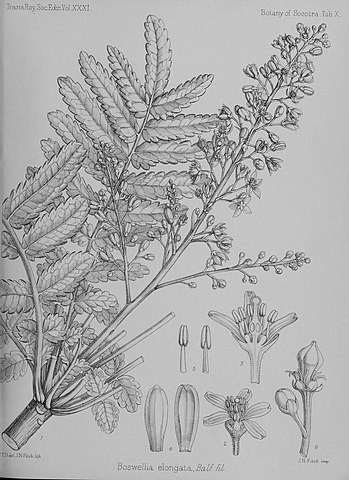

Boswellia Sacra

Family: Burseraceae

Arabic: luban, kundur, اللبان al-liban, البخور al-bakhur

Omani: hojari هوجاري (also hawjari, hojari, houghary, hogary),thiki, nejdi, shahazi.

Jibbali: megerot (tree)

Dhofari Arabic: sajerat alluban, mugereh (tree)

Jibbali: sahaz (gum-resin)

Greek/Latin: libanos, libanus and olibanum

English: Frankincense

Pharmacology: gummiresina olibanum, thus.

Botantical synonym: Boswellia carteri

The Greek Λίβανος and Latin words for frankincense, libanos, libanus and olibanum , come from Arabic luban, which, like the South Arabian libnay, derives from a root that refers to “milky whiteness.”

The Arabic scientific name for the gum, kundur, seems to derive, possibly via Persian, from a Greek pharmaceutical term, khondros libanou —”grain frankincense.”

Other names include Latin: tus, Persian: کندر [Kondoor], Syriac: ܒܣܡܐ [bisma], Hebrew: לבונה [levoˈna], Arabic: اللبان al-liban or Arabic: البخور al-bakhur, Hojari هوجاري Somali: Foox or Somali: Lubaan, Chinese: Ruxiang or xunluxiang .

These are some of the chemical compounds present in frankincense:

- acid resin (6%), soluble in alcohol and having the formula C20H32O4

- gum (similar to gum arabic) 30–36%

- acetyl-beta-boswellic acid

- alpha-boswellic acid

- incensole acetate, C21H34O3

- phellandrene

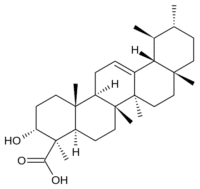

Among various plants in the genus Boswellia, only Boswellia sacra, Boswellia serrata and Boswellia papyrifera have been confirmed to contain significant amounts of boswellic acids.

The chemical structure of boswellic acids closely resembles that of steroids, but their actions are different from painkillers or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and are related to the component of the immune system and the inhibition of 5-lipoxygenase.

Boswellic acids has shown powerful anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer activity in laboratory studies. They are the Frankincense resin acids which are pentacyclic triterpenes. In recent years, the pharmacological research on frankincense has focused on other pharmacological effects, including anti-ulcer, memory improvement, and anti-oxidation.

The gum extracts or resins from Boswellia sp. and their triterpenes, especially BA, have attracted the attention of pharmacologists, medicinal chemists, and biochemists as therapeutic agents due to their efficacy in treating rheumatoid arthritis and chronic inflammation without side effects and toxicity.

The gum obtained from the bark of the tree B. serrata, also called Indian olibanum, has been extensively used in the treatment of arthritis, asthma, ulcers, and skin diseases by practitioners of Indian traditional medicine

Geographical distribution of frankincense producing countries: Preservation and sustainability

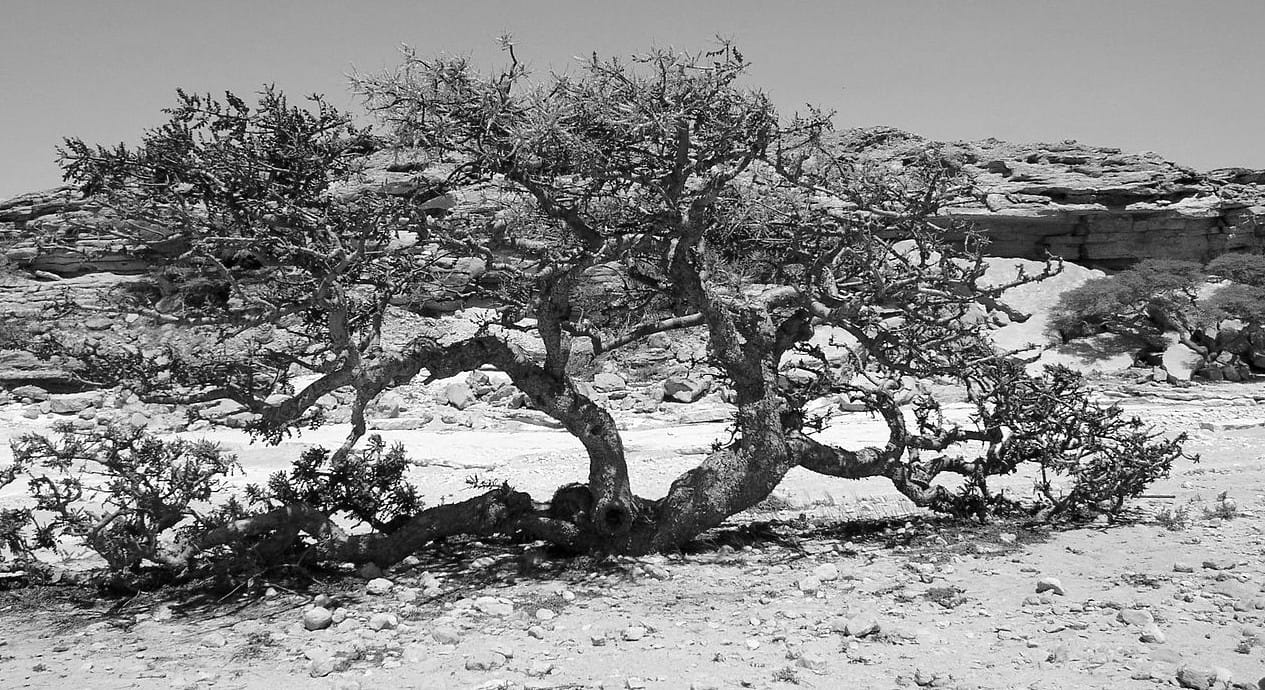

The tree Boswellia, which produces the frankincense resin gum, is found not only in southern Arabia, but also in Somalia and India. Of the 25 or so species of Boswellia, the one generally agreed to produce the finest frankincense is Boswellia sacra, which grows exclusively in Oman, Dhofar and, to a lesser extent, in the Al-Mahrah and Hadhramaut regions of Yemen.

All the major medicinal species of Boswellia are threatened or endangered. Ten types of Boswellia trees are currently on the Red List of threatened species. The tree is under considerable pressure in many areas due to overgrazing, by goats and especially camels, fire and indiscriminate over tapping. Researchers suggest better forest management is the key to restoring Boswellia populations in order to continue frankincense production in the future.

Currently the vast majority of frankincense comes from Boswellia papyrifera, which as shown grows in a belt stretching from the Horn of Africa in Eritrea and Ethiopia cross Sudan and into the Central African Republic and Cameroon, with small distinct populations in Uganda and Niger. Boswellia sacra, principally found in northern Somalia and Oman and Yemen.

The Frankincense harvest

The harvest, on the trees located on the coastal plain or during the monsoon, is done from the end of March to June, approximately.

For those located behind the Dhofar mountain (desert area), the resin is picked from April to September.

As soon as the temperatures start to rise, the frankincense gatherers taqii cut the Boswellia trees using a manqaf or menghaf (a traditional Arabic tool like a miniature scythe).

The first ‘cut’ is called the tawqii and consists of paring off the outer bark of the branches and trunk. This causes a milky-white liquid to ooze from the tree which quickly solidifies and is left in this condition for 14 days or so.

The second ‘cut’ called “white incense”, which follows this period, produces resin of an inferior quality and the real harvest begins two weeks after the second ‘cut’. With this third ‘cut’ the tree produces frankincense resin of yellowish color.

“Brown incense” is harvested only on the coastal plain after winter incisions.

The ‘cutting’ of the frankincense trees calls for great skill. The harvest lasts for 3 months and the average yield of frankincense resin for one tree is around 3-4 kilos.

The Governorate of Dhofar produces approx. 7000 tons of frankincense annually.

Omani use of hojari or frankincense

Incense and bokhur (bakhoors) is used daily in most Omani homes. Omani villages have their own bokhur maker who produces an incense blend unique to that area using various ingredients, such as rosewater, sugar, ambergris, sandalwood, frankincense and myrrh. Also powdered flowers, perfumed oils, ground seashells, and other aromatics are used.

Bokhur is smouldered in an incense brazier made from clay, porcelain or silver, it is scattered over hot charcoals, releasing the fragrance which will permeate clothes and furniture.

The airport, shops and other government buildings in Oman are incensed daily, even the elevators. Outsized incense burners smolder in significant public places: Brazier-sized ones flank the entrance to the sultan’s palace outside Muscat. And truly gigantic sculptures of incense brazers can be found in urban traffic circles, where they sometimes function as fountains.

Smoking frankincense resin is also believed to protect from evil, and this is a key element for many people in its daily use within a home, official building or in a car.

Omani families soak their clothing with the smoke, using a wicker frame called a makhbarah. In the morning, hojari is used regularly in the kitchen and the living room. In the evening, it is smoldered in bedrooms. Omanis fumigate to perfume clothing and home spaces, and eliminate cooking smells.

The incense can be carried around and its smoke is wafted into a person’s beard or over one’s body. The courtly ceremonies of hospitality — the graceful pouring of coffee, the dates and sweets delicately proffered — are performed in an atmosphere perfumed by frankincense. After dinner or house functions, incense is smouldered as a sign of farewell.

“After the incense, there is no sitting on.”

an Omani proverb states.

For weddings, Frankincense is burnt just before the ceremony. During the birth of a child, incense is used throughout labor to protect the mother, and also after safely delivering her baby. Incense is also burnt near the baby’s cradle to honor and protect new life. During and after birth, frankincense was smouldered for 40 days to protect mother and child.

Whenever a serious matter was to be decided or a pact made, this would normally be solemnised and ratified not only by an exchange or drink between the parties to the contract, but also by the burning of frankincense. Frankincense was often burned too during the ritual of swearing an oath over the graves and shrines of certain revered, sanctified men in a traditional ceremony long practiced in Dhofar.

The large wooden or clay containers used to store water were cleaned out and fumigated with frankincense – every fortnight or so they were emptied, scrubbed out and then a smoking frankincense burner was lowered in and more gum dropped onto the red coals.

The container was then securely covered and left until thoroughly impregnated with smoke. The frankincense burner was removed and fresh water quickly poured in, and the container covered over once more. This practice gave the water a distinctive flavor and perfume.

The dried gum was made into a fine powder by crushing and grinding it down, and then mixing it with other fragrant powdered woods and spices-according to the pocket of the woman who was making the mixture-in order to make a sort of talcum powder which was rubbed into the skin to perfume it and make it soft and smooth to the touch.

Apart from the various uses of the gum in ceremony and medicine, powdered frankincense was also used to produce a long burning taper whose flame was very hard to extinguish. A mixture of pitch, sulphur, tow, pinewood sawdust and powdered frankincense was smeared over a wooden stave and set alight. These burning brands were apparently used with great success to set enemy strongholds on fire.

An different use of the bark was described by Greek physician Dioscoridos: it was put into water to attract fish, luring them into nets and traps.

Frankincense also connects Omani urban life to their heritage, to nature, and to spiritual life.

The Incense that is also a Medicine in Oman

In “The Plants of Dhofar,” the 1988 ethnobotanical guide published by the Sultanate of Oman there are more medicinal uses:

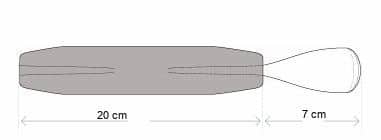

“The fresh gum was used in the treatment of fractures – a broken limb was often treated by splinting it between two thick slices of frankincense bark which had been smeared with fresh frankincense gum. This coating of gum set hard when it dried, providing a rigid casing to support the damaged limb as it set. This property of hardening to produce a waterproof, firs (but not brittle) surface was also exploited with great success in the repairing of cracked or holed clay vessels, and even on occasion metal ones too.

Frankincense gum, fresh or dried, as also used in the treatment of mastitis, in both livestock and humans. It was either boiled in the milk of the patient until a thick paste resulted, which was then smeared over the affected part; or mixed with ground cuttlefish bone and soured milk and boiled down to a paste, also locally applied.

The fragrant smoke resulting from the burning of the dried gum was considered to have powerful curative and protective properties. A sick person (or indeed animal-most remedies applied to livestock as well as to their owners) would be fumigated with frankincense.

Someone believed to have been laid low by the evil eye or struck down by malevolent influences or by ‘spit’ would have a bowl of burning frankincense leaves placed at their head, while relatives (or invited specialists known to have specific and recognized powers in these kinds of cases) circumambulated the patient, bearing a second burning bowl of frankincense, while murmuring various incantations and invocations.

This ceremony was repeated (though possibly in a more simplified version) at intervals during the illness – and especially at night – that most dangerous and hostile time – to keep the jinn and other menacing spirits away.

Since most serious or prolonged illnesses were considered to be the result of inimicable action on the part of someone or something, such fumigating treatment was a regular feature of any course of treatment, as well as being used as a prophylactic.

Someone suffering from a head cold would breathe in the smoke of burning frankincense gum, with or without added sugar sprinkled over the smoldering charcoal and during and after a circumcision operation, smoke from the burning gum would be wafted around the patient and particularly around the site of the operation, the wound then being anointed with dried camel dung or with a salve prepared form various plant mixtures.

At the Sultan Qaboos Grand Mosque, high-quality frankincense burns in the underground air-conditioning plant, and has its scent wafting over shelves holding Korans and into the men’s hall that has space for six thousand worshipers.

“To smell good in the mosque is a sign of respect for your religion and fellow man,” observes a follower of Islam . “It prepares your little soul to meet the big soul.”

The Prophet Muhammad (p.b.o.h.), who advised his people to wear perfume for Friday noon prayers, smelled “heavenly,” his companions reported. Even the beads of sweat on his forehead smelled wondrous.

ETHNOBOTANY/ETHNOMEDICINE: Frankincense as Materia Medica

The study of how people of a particular culture and region interact and use indigenous plants and how they classify, identify and relate to them is called Ethnobotany. Ethnomedicinal information gathered from indigenous knowledge relating to traditional Frankincense uses revealed, that the resins enjoy a wide array of traditional uses in human medicine due to it’s therapeutic properties.

Medicinally, the gum was used in the treatment of almost every imaginable disease by Arabic, Indian, Chinese, Greek and Roman physicians.

That is why remedies employing frankincense appear in the Syriac Book of Medicine, in the texts of the Arab practitioners of the middle ages and in Indian and Chinese medical writings. It has been used in the Traditional Medicine systems of Asia, Europe, Arabia and Africa for thousands of years.

A short list of traditional therapeutic applications associated with Frankincense would include — treating arthritis, rheumatism, ulcers, asthma, bronchitis, gastrointestinal disorders, tumors, cancers, infertility, moods, anxiety/depression and memory loss, improving brain function, addressing ageing skin and flagging libido.

Medicinal uses of Frankincense by country

Arabic peninsula: Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen

In Arabia Frankincense has been chewed for millennia for oral care, ulcers and general physical/mental well-being. It has been used as an aphrodisiac and to treat infertility in both men and women. It is taken sometimes as a tea steeped in boiling water overnight and sipped during the day for inflammations, coughs, congestion, and colds.

Arabian lore also indicates that large testicle shaped Frankincense tears, (sometimes called Dakkar, from the Arabic word for masculine), are sexual tonics and aphrodisiacs for men, while pieces more vulvic in shape are believed to have similar effects on women.

It is narrated that Hazrat Abdullah Bin Jaffar Radi Allaho Anh said:

بَخِّروا بُيُوتَكُم باللُّبان والصَّعْتَ

Fumigate your houses with Lubaan (Frankincense) and Sa’atar (Thyme).

Iran

In traditional Iranian medicine, Frankincense is still consumed by pregnant women to increase the intelligence, (and bravery), of their offspring, and is generally considered to contribute to one’s mental acuity, emotional stability and spiritual clarity. Boswellia has been widely used in traditional medicine for the treatment of different diseases such as cancer in Iran. It is sometimes used as a general tonic and restorative.

China

In the Chinese medicine books, frankincense was first mentioned in the Mingyi Bielu 名醫別錄(Miscellaneous Records of Famous Physicians; ca. 500 AD).

The Ming dynasty work Formulas for Universal Benefit lists, as does Selected Materials for the Preservation of Health (Jisheng bacui fang, 1315). The prescription was comprised of huangdan, huanglian, huangqin, dahuang, huangbai (Chinese cork tree), and ruxiang

(frankincense), for

“curing wounds inflicted by a stick zhangchuang decreasing swelling, drawing out pus, and reducing swelling.”

It was called Fan Hun Xiang, fanhunxiang (calling back the soul fragrance) and Ru Xiang, ruxiang 乳香 (nipple-shaped fragrance); the latter name has been retained, but the former is true to the original use of frankincense as incense for mourning the dead.

In traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) it is beneficial for the heart, liver and spleen meridians. Ru Xiang moves Qi, invigorates blood, prevents stagnation, reduces swelling, generates flesh and relaxes the sinews, invigorates the channels, alleviates pain – bi syndromes, rigidity and spasms.

Fan Hun Xiang in TCM finds application in: amenorrhea, dysmenorrhea or postpartum abdominal pain due to blood stasis, blood stasis related to traumatic injuries, painful swellings, masses, chest or abdominal pain due to blood stagnation, cancer, asthma, wheezing, shortness of breath, headaches, promotes the free flow of Qi and Blood in the Meridians, relieves rigidity and spasms, topically to reduce swelling, generate flesh, alleviate pain and promote healing of wounds and sores, includes acne, sore mouths and gums, leprosy.

Boswellia, in TCM is taken orally as a powder, tablet, or its bark decoction.

Africa

Boswellia Sacra or B. Carterii and B. Frereana from Somalia have also been used to address issues of fertility in men and considered aphrodisiacs. Though Boswellia Frereana from Somalia does not contain Boswellic acids, it is also a powerful anti-inflammatory used traditionally to treat inflammations of joints and arthritis.

Laboratory studies show it can reduce brain inflammation due to tumours, head injuries and stroke. It kills the H.pylorii bacteria which causes stomach ulcers.

It is valued as a traditional high-end chewing gum for oral and gastrointestinal health.

Boswellia Papyrifera from Ethiopia/Eritrea/Kenya and Sudan, which is a source of Boswellic acids, also contains Incensole acetate which is considered a psychoactive compound that crosses the blood-brain barrier, reducing anxiety and eliciting feelings of heightened spirituality and well-being.

The incensole and Incensole acetate are delivered to us when using the whole oleoresin internally, through pyrolysis- burning as an incense, and when using the diluted essential oil externally.

Turkey and Jordan

Boswellia Thurifera from the shores of the Red Sea has been shown in the laboratory, to have effect on the reproductive system in adult rats, raising their sperm count and having effects on fertility of female rats.

European Antiquity

Learning from “The Canon of Medicine”, Arabic al-Qanun fi t-Tibb, by the Persian doctor Avicenna, the Greek Dioscorides prescribed Boswellia serrata and Boswellia sacra for internal use. Recommending it for

“strengthening the spirit and understanding”.

The Roman Empire was a large consumer of incense. Hippocrates and other Greco-Roman doctors used incense to cleanse wounds, treat respiratory diseases and digestive problems. Nothing was known about the mechanisms of action, but the practical successes were numerous enough that the expensive substance was used as medicine in the Middle Ages, including by Hildegard von Bingen.

According to the medieval mystic and polymath Bingen’s Physica, frankincense “clarifies the eyes and purges the brain taken baked into cakes.” She recommends topical use for severe headaches and malarial fevers.

From ancient times through the Middle Ages to the 18th century, frankincense resin was used as a powder directly or as a healing plaster ingredient to treat wounds.

The development of chemical-synthetic drugs, especially in the classes of antibiotics and corticosteroids, caused frankincense to be forgotten as a drug. With the return to natural remedies and the promotion of research into natural remedies, frankincense again became the focus of medical interest.

India

Boswellia serrata (Hindi – Loban लोबन or salai guggal) is used extensively in Ayurvedic medicine of India.

In Ayurvedic medicine, it is an important anti-rheumatic drug. Contemporary studies have shown that olibanum indeed has analgesic, tranquilizing, and anti-bacterial effects. From the point of view of therapeutic properties, extracts from Boswellia serrata and Boswellia carteri are reported to be particularly useful. They reduce inflammatory conditions in the course of rheumatism by inhibiting leukocyte elastase and degrading glycos-aminoglycans (in joints with inflammatory lesions).

The oldest source on incense is the Vedas, specifically, the Atharva-veda and the Rigveda, which set out and encouraged a uniform method of making incense.

This texts mention the use of incense for masking odours and creating a pleasurable smell, the modern system of organized incense-making was likely created by the medicinal priests of the time.

Various resins, such as amber, myrrh (Guggal, Commiphora wightii ), frankincense, and halmaddi (the resin of Ailanthus triphysa tree;) are used in traditional masala incense sticks, also called Agarbatti.

The method of incense making with a bamboo stick as a core originated in India at the end of the 19th century, largely replacing the rolled, extruded or shaped method which is still used in India for dhoop and cones, and for most shapes of incense in Nepal/Tibet and Japan.

Other main forms of incense are cones and logs and benzoin resin (or sambrani), which are incense paste formed into pyramid shapes or log shapes, and then dried.

“Accompany your prayer with perfume

and your words will reach God transported by an odorous exhalationtelling him of your gratitude and devotion”

Vedas of India

Some limitations must be considered. More studies are required to elucidate the antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory mechanisms exerted by frankincense extracts and compounds. Also pre-clinical and randomized clinical trials, are needed to better understand the beneficial effects of frankincense extracts and compounds on human health.

Note:

This post does not contain medical advice. Please ask a health practitioner before trying therapeutic products new to you.

If you do wish to experiment, we suggest doing further research. Frankincense for internal use must be sold as such.

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- Al-Kamali Reem. Frankincense, the story of a tree that continues to weep for love. https://english.alarabiya.net/views/news/middle-east/2017/05/26/Frankincense-the-story-of-a-tree-that-continues-to-weep-for-love

- Ben-Yehoshua, Shimshon & Borowitz, Carole & Hanus, Lumir. Frankincense, Myrrh, and Balm of Gilead: Ancient Spices of Southern Arabia and Judea. Horticultural Reviews. 2012.

- Bongers F, Groenendijk P, Bekele T, et al. (2019) “Frankincense in peril” Nature Sustainability 2:602–10.

- Boswellia sacra. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boswellia_sacra

- Boswellia. https://www.botmed.rocks/boswellia-spp.html

- Brendler T, Brinckmann JA, Schippmann U (2018) “Sustainable supply, a foundation for natural product development: The case of Indian frankincense (Boswellia serrata Roxb ex Colebr)” J Ethnopharmacol 225:279–86.

- Following the frankincense trail. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/90992/following-the-frankincense-trail

- Frankincense Uses. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frankincense#Uses

- Frankincense via Plants of Dhofar Guide. https://www.enfleurage.com/frankincense-via-plants-of-dhofar-guide/

- Frankincense. http://www.mei.edu/sqcc/frankincense

- Frankincense. https://www.hellenicgods.org/frankincense Thank you.

- http://www.bestiary.ca/beasts/beast149.htm

- http://www.salut-virtual-museum.org/index.php?id=32

- https://amp.theguardian.com/travel/2001/may/05/oman.guardiansaturdaytravelsection

- Frankincense medicine truth myth and misinformation. Thank you.

- https://omanisilver.com/contents/en-us/d232.html#p235

- https://seekersguidance.org/answers/general-counsel/what-is-the-place-of-frankincense-in-the-sunnah/

- https://timesofoman.com/article/97514

- Land of Frankincense. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1010-

- https://www.blackwoodconservation.org/5000-year-history/

- https://www.cntraveler.com/stories/2012-12-26/oman-luxury-perfumes-fragrances-scents

- https://www.encens-naturel.eu/en/dhofar-production-of-frankincense

- https://www.outlookindia.com/outlooktraveller/explore/story/46808/oman-history-of-omani-frankincense

- https://www.theglobeandmail.com/world/article-frankincense-omans-white-gold-loses-its-lustre-in-a-modernizing/#sidebar

- In the Cradle of Scent. https://www.cntraveler.com/stories/2012-12-26/oman-luxury-perfumes-fragrances-scents Thank you.

- Incense Route. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Incense_Route

- Incense Route. https://www.livius.org/articles/place/incense-route/

- Land of frankincense. http://www.omanobserver.om/land-of-frankincense/

- Land of Frankincense. https://web.archive.org/web/20240301042710/https://omanvisitors.com/land-of-frankincense/

- Land of Frankincense. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1010/gallery/&index=1&maxrows=12

- Land of frankincense. https://web.archive.org/web/20250320091336/https://www.worldheritagesite.org/list/Land+of+Frankincense

- Mackintosh-Smith T.. Scents of Place. Frankincense in Oman. https://archive.aramcoworld.com/issue/198706/old.scent.new.bottles.htm Thank you.

- Oman History: Explore the ancient Omani trading routes. https://timesofoman.com/article/100895/HI/This-Weekend/Oman-History-Explore-the-ancient-Omani-trading-routes

- Oman legends that live on. http://www.omanobserver.om/oman-legends-that-live-on/

- Oman the land of frankincense.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses4.192–270

- Replicating the slightly plantable gifts of the magi in the garden. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/08/garden/replicating-the-slightly-plantable-gifts-of-the-magi-in-the-garden.html?_r=1

- Salalah Oman. Pics from https://oilygurus.com/farms/salalah-oman/

- Smith William. A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. 1880.

- The frankincense tree. https://web.archive.org/web/20171129222134/http://timesofoman.com:80/extra/frankincense/phone/the-frankincense-tree.html

- The Great Trade Routes: The Scent Route. https://thejourneytotheeast.com/the-scent-route-europe-asia/

- The land of Frankicense. https://www.herbalhistory.org/home/the-land-of-frankincense/

- What is frankincense. https://www.learnreligions.com/what-is-frankincense-700747

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292140720_Frankincense_-_therapeutic_properties

- https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Weihrauch