The “hoja sagrada” or sacred leaf has enormous significance to Aymara and Quechua people in the Andes. Discover the coca leaf in South American tradition, it’s social and ritual uses.

In this Article

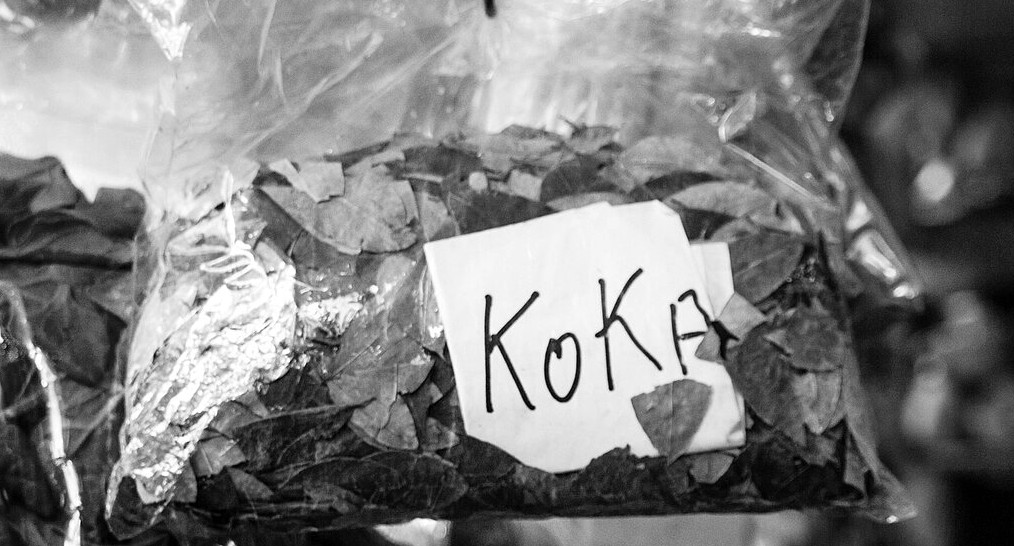

Traditionally, Andean communities value the leaves of the coca plant (Erythroxylum coca) in religious and social rituals.

Coca leaves are known for their strength giving properties, which are helpful in cultivating crops, but also for their ritual importance as an offering to the gods.

Coca is not cocaine. Coca is medicine, food, drink, coca is fundamentally cultural.

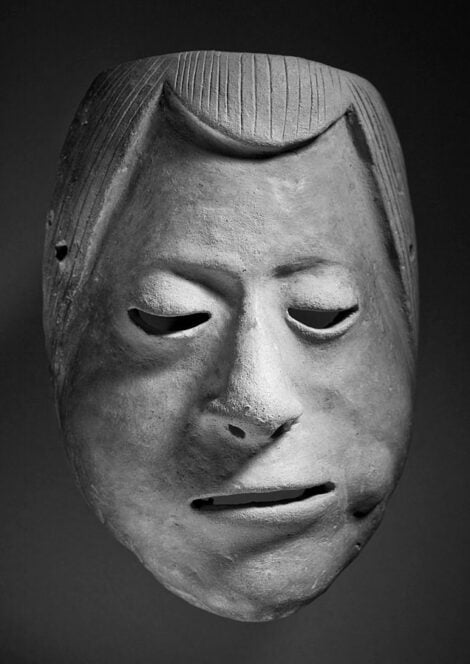

Moche portrait vessels of Peru

Ethno-historians and anthropologists who researched Spanish chronicles, as well as archaeologists, suggest that the coca leaf had great meaning for the pre-Inca Andean peoples.

Moche (100 BC. to 800 CE.) portrait vessels feature naturalistic representations of human faces that are highly individual and expressive. From northern Peru, this vessels show figures of possible shamans, rulers or soldiers, that appear with their cheeks dilated by the bola or acullico. This depictions are keeping a saliva-soaked ball of coca leaves in the mouth together with an alkaline.

Ayllus

The ayllus – traditional, socioeconomic organization of a community in the Andes, especially among Quechuas and Aymaras of Lake Titicaca had common coca fields in the Yungas of the current department of La Paz, Bolivia.

Traditionally, the agricultural cycle of coca depended upon the reciprocal labor of women and men, from clearing new or fallow land, building terraces and planting the coca seedlings, to harvesting the leaves and seeds. This ancient practice of Andean reciprocity called ayni builds relationships of trust and mutual aid within and between rural communities.

Before the Spanish arrived at the borders of the Inca Empire in 1528, textiles and coca leaf were the most valued commodities. As such they were commonly used in trade or as compensation for labor, and as a ritualistic element of exchange.

Such use of coca was only one component of a comprehensive system of barter exchange called trueque, by which products and labor, not money, were traded within and between communities. The fundamental Andean cultural values of ayni and trueque were the foundation of the ancient kinship networks of the ayllu communities

The sacred plant of the Incas: la coca

The founding myth of the Inca empire itself was related to coca. Garcilaso de la Vega, when recounting the legend of the children of the sun who founded the empire, pointed out that they had offered coca leaves and taught the people that they could be used to kill hunger, eliminate fatigue and allow the unfortunate to forget their misfortunes.

It is also through the lens of the conquistadores that we learn about religion in the Inca Empire. While the indigenous author Pedro Cieza de León wrote about the effects coca had on the Inca and

Called it the “Divine Leaf” by the Inca, coca was considered the highest form of plant offering that they made.

Pedro Cieza de León

Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa, Father Bernabé Cobo, and Juan de Ulloa Mogollón also tell us about the importance of coca in Inca spirituality, and noted how the Incas would place coca at important locations throughout the empire.

Since ancient times, its leaves have been an important trade commodity between the lowlands, where it is chiefly cultivated, and the higher altitudes, where it is widely consumed.

Sacred Inca mummies

Traces of coca have been found in archaeological evidence dating back 8000 years, with mummies discovered buried with a supply of coca leaves and potatoes, along with pottery decorated with depictions of figures displaying the characteristic cheek bulge of the coca chewer.

Mummification was reserved for royalty, the bodies were prepared for burial by placing them in a sitting position with the knees drawn up and the head and hands resting upon them, as is shown on the right. As a sacred ritual, Inca would put coca leaves in the mouths of mummies and give them the leaves in bags, called Chuspa or huallqepo.

Mummies of Inca emperors were regarded for their wisdom and often consulted for important matters long after the body had deteriorated.

Barter economy

The empire arranged the establishment of plantations to maintain a stable production of coca, they were property of the Inca. The exchange of coca leaves for meat, potatoes, beans, chocolate, quinoa, vegetables was a common practice for the Incas, meaning that coca leaves played an important part in their barter economy.

The Incas had a postal system across their territory, and the couriers, known as ‘chaskis or chasqui, ‘ were usually athletic, young men, who traveled the empire on foot.

This group made extensive use of coca leaves, as their consumption enabled them to perform their duties and cover great distances without feeling fatigued.

Ritual Coca

Coca was also used in divination as ritual, priests would burn a mixture of coca and llama fat and predict the future based on the appearance of the flame. Fortune-tellers also chewed coca leaves and spit the juice into the palm of their hand with outstretched fingers to predict good or bad omens.

Inca priests, the nobility and the doctors of the court would consider the leaf as sacred. Chroniclers say that the Incas gave coca to the ethnic authorities who arrived in Cuzco, as part of the reciprocity between the State and the dominated groups.

Furthermore, along with other products, like potatoes, quinoa and maize, this leaf was stored in qullqas, provincial warehouses, to be used in times of war and was distributed among the needy in times of peace, to alleviate the needs of the population in case of food shortage.

Ritual coca leaf reading

No one knows how long the tradition of coca reading exists in the Andes. For Quechua and Aymaras of today, coca is still a gift from Inti, the sun god, there its magical value is born, the rituals, that can advise, deliver visions or special knowledge. Its use in shamanic rituals is well documented wherever local populations have cultivated the plant.

Coca leaves serve the “yatiris” (those who know, shamans) to carry out a large part of their spells and their omens. By throwing the leaves on a traditional “haguayo” fabric, they are said to read the future and past.

According to tradition, the ceremony’s master has acquired the skill from his own ancestors and will pass it on to future generations.

After the formulation of the question, an invocation is made, asking the spirit of the plant, Mamacoca, for permission to begin the reading and to transmit the will of Pachamama.

To obtain information about an absent person’s health, behavior, or business, the client must take their clothing or objects of daily use: they are held out by the client and the coca leaves are thrown on top. It is preferable to choose old clothes that have not been washed, thus ensuring better communication. In the same way, it is said that you can see the image of a deceased person on its clothes.

A person who wonders about the intentions of his or her partner can consult a “yatiri” also. Accompanied by mystical-religious prayers, the yatiri will give coca leaves to the client, which must be touched by the partner. The leaves are then returned to the yatiri, who will ceremoniously drop the leaves to the ground.

The answer depends on how the leaves fall. The yatiri interprets the answer to the question based on the arrangement of the leaves in relation to each other, the color of the leaves in a predominant position, the material condition (if they are folded) and integrity, the exposed faces (upper or underside) and the orientation of its conical tip, among other details.

If the reading is carried out in the context of traditional medicine, the yatiri will identify the disease and the therapy. If he cannot treat the illness, he will send the patient to a hospital for modern medicine.

K’intu, the sacred coca offering

Today, the K’intus, coca leaves, play a crucial part in offerings to the apus (mountains), Inti (the sun), or Pachamama (the earth). The offering ceremonies, commonly known to the Andean communities as, “payments to land or payments to Pachamama” are part of a system of reciprocity between the material world and the spiritual world, between human beings and nature.

With the ritual, Quechua and Aymara people would, symbolically return some of the resources provided by Pachamama. For the Andean communities, the offerings are a way to reconcile with the spiritual forces in order to avoid misfortunes. The leaf represents a sacrifice that is deposited in specific places, like roadside shrines, and is used in ceremonies to receive protection and promote good harvests.

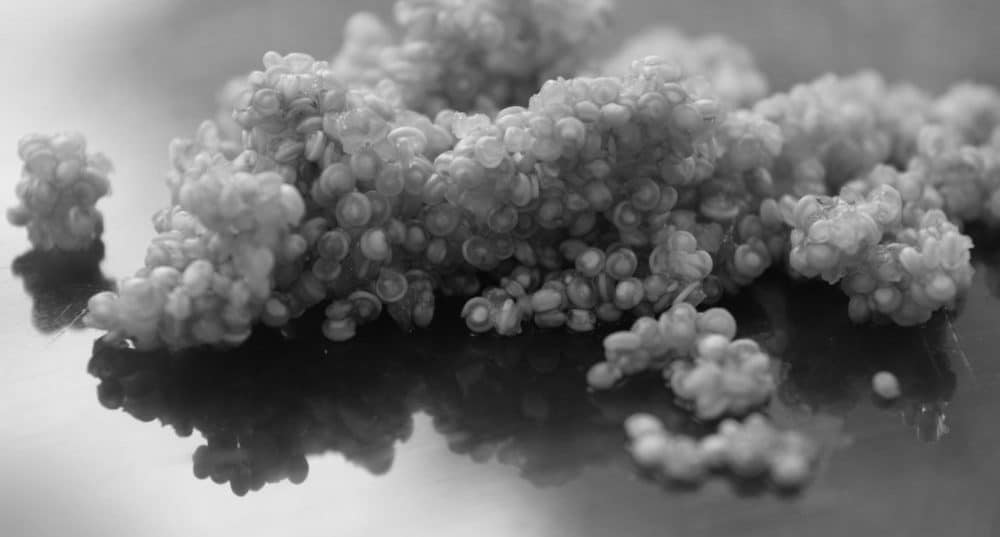

Depending on the cultural tradition, the number of selected leaves ranges from 2 to more leaves.

The pukuy: to blow gently on the coca leaves

In Quechua communities around Cusco,it is considered good manners to perform a pukuy (‘blow a kintu’) before putting the coca leaves in your mouth. American botanist Timothy Plowman in his: The Ethnobotany of Coca , 1984, describes the ritual in the assembly of the kintu:

The first step is to select two or three leaves from the coca bag. These are known as k’intu. They are carefully placed one on top of the other, holding them between the index finger and thumb.

The k’intu is held in front of the mouth and blown gently on the leaves, at the same time the coquero invokes the deities and spirits of the mountains (apus) and sacred places. This act is called pukuy. The leaves can then be used for chewing or are crushed and then blown in the wind with new invocations.

Such regular devotional acts help weave the web of reciprocity that connects humans with

Catherine J. Allen

the sacred places of their divine geography and with the legacy of their ancestors .

Chewing coca is a social act

Chewing coca leaves is most common in indigenous communities across the central Andean region, particularly in places like the highlands of Argentina, Colombia, Bolivia, and Peru, where the cultivation and consumption of coca is a part of the traditional culture, similar to chicha (maize or quinoa beer).

Archaeological evidence has shown, that Coca chewing is about 8,000 years old – it is a deeply rooted economic, social and religious tradition in the Andes.

It also serves as a powerful symbol of indigenous cultural and religious identity, among a diversity of indigenous nations throughout South America.

Coca fundamentally constitutes a means of social cohesion in the Andean world. In celebrations such as births, marriages or funerals where the community gathers, coca cannot be missing – as sharing the leaves creates social relationships.

In “Travel medicine, coca and cocaine: demystifying and rehabilitating Erythroxylum – a comprehensive review“, Irmgard Bauer writes:

Coca is a strong marker of cultural identity for many Andean communities. It is crucial in acknowledging and maintaining social bonds. Friendship and affection are demonstrated by chewing together; refusal is perceived antisocial.

Religious aspects of coca are evident through shamans’ divinations, at animal sacrifices and burials, but also in everyday life such as a gift to a potential bride’s father, during carnivals and celebrations, even as inspiration for weavers.

Strict etiquette rules the highly ceremonialized handling, sharing and use of the leaves. Coca is part of important economic activities on a local level, for rural women trading in traditional medicines, and nationwide.

The Koguis (Tayronas) of Colombia’s Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta would chew the plant before engaging in extended meditation and prayer.

In rites of passage of the Koguis, an indigenous group that resides in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountains in northern Colombia, when a boy is ready to be married, his mother initiates him in the use of the coca.

He gets a poporo, a small, hollow gourd filled with lima (“lime”). This act of initiation is carefully supervised by the Mamo, a traditional priest-teacher-leader of the Koguis of Colombia.

From that point, the men would chew coca leaves, a tradition followed by many indigenous tribes to connect them to the natural world. As they chew the leaves, they suck on the lime powder in their poporos, which they extract with a stick, and rub the mixture on the gourd with the stick to form a hardened layer or crust.

The size of this layer depends on the man’s maturity and age. When two Kogi men meet, the customary greeting is to exchange handfuls of coca.

It is believed by the miners of Cerro de Pasco, Peru, use coca to soften the veins of ore, spitting chewed coca upon them.

The coca leaf is still used in celebrations today, just as it has been for thousands of years in the Andean culture. It’s considered a cherished gift and a way to show honor and respect to the receiver.

When a Peruvian male ask a girl to marry him, he often presents her father with coca leaves. When a new baby is born, the father often passes out coca leaves to friends and relatives to celebrate the occasion.

When a person is laid to rest, leaves chewed by those in attendance are placed in the coffin to assist in the journey to the next world and as a greeting to their ancestors. For these reasons and many more, it is easy to understand why coca, is the sacred leaf.

The medicinal application of coca continues to be by the traditional healers and spiritual leaders of indigenous Andean communities, such as the Kallawaya yatiris of Bolivia and the Kogi mamas in Colombia, who have practiced their craft for millennia.

Southamericans chew the leaves to eradicate hunger, thirst, improve muscle stamina, to counter motion sickness and oxygen deprivation. In its natural form, the leaf is also used in teas, in cooking and for religious rituals.

Despite the strength and pervasiveness of coca culture in South America, ever since Spanish conquistadores arrived in the Andes in the 1500s coca has been used as a tool of exploitation. The profits and benefits of the coca economy have largely benefited a handful of elite private interests, the Spanish Crown, hacienda owners, silver and tin barons, European pharmaceutical companies, the Coca-Cola Company, drug cartels, offshore banks…

Andean and Amazonian indigenous groups have tried to resist such political and economic manipulations, and they often used coca as symbol and sustenance of their resistance.

Decriminalizing chewing coca

Bolivian President, Evo Morales, once a coca grower, campaigns for decriminalizing chewing coca leaves.

The indigenous people of Bolivia declared coca leaves a ‘cultural patrimony’ in the Bolivian constitution in 2009.

Bolivians believe the coca plant is sacred and defend the spiritual, social, medicinal, economic and political value of the coca plant.

Carlos Crespo, a researcher and professor at the Universidad Mayor de San Simón (UMSS) in the city of Cochabamba in the center of Bolivia, chews coca. He is one of the promoters of the new, Organic Coca Marketing Network.

“There is no control of the quality of coca for traditional consumers. We do not know if the coca we are chewing has had chemicals such as herbicides, etc. As a chewer, I have to trust the word of the person who sells me the coca, I have no other choice,” he says.

Coca Machucada

In Bolivia a “new” trend is potentially harmful, it is crushed coca leafs that has been soaked in flavors, like coffee, bubblegum, banana etc. and then mixed with bicarbonate of soda and sweetener. This cocktail, known as “coca Machucada”, is often consumed accompanied by an energy drink.

Luis Fernando Rojas, head of the Public Health Information Unit of the Departmental Health Service (Sedes) of Cochabamba, confirms that “today, the leaf is contaminated with chemicals for consumption.” In his opinion, “the companies that produce these products should be required to disclose what substances they incorporate into “coca Machucada” or crushed coca and conduct studies to establish their relationship with various diseases.”

In his recommendation to the public, Dr. Gutiérrez urged them not to be misled by propaganda and to carefully research the products they consume.

“It’s essential to know the origin and ingredients of what we’re consuming,”

he said, suggesting they avoid crushed coca and return to a more natural and moderate consumption of the plant.

Coca leaves are a cultural symbol of Andean society, a gift from Pacha Mama or sun god Inti, and an integral part of daily economic, religious, political, and medical life.

In the majority of the Andean communities, the “sacred leaf” actively participates in daily and ceremonial activities similar to those of the ancient Andeans. The leaf maintains its protective, spiritual, medicinal, and sacred qualities, assuming fertility, security, and well-being to those using it into the 21st century.

Coca as a cultural good is increasingly deployed as a symbol of solidarity and resistance in

indigenous struggles against outside forces of oppression and exploitation

Roadmaps to Regulation: Coca, Cocaine, and Derivatives

NOTA BENE:

The cultivation, sale, and possession of unprocessed Coca leaf is generally legal in Bolivia, Peru, Chile and Argentina – where traditional use is established, although cultivation is restricted.

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- Allen Catherine J. The Hold Life Has: Coca and Cultural Identity in an Andean Community. 2002.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20220706183728/https://www.tni.org/en/primer/coca-leaf-myths-and-reality

- Roadmaps to Regulation: Coca, Cocaine, and Derivatives

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303315045_The_Botanical_Science_and_Cultural_Value_of_Coca_Leaf_in_South_America

- https://www.monah.org/artifact-blog/2020/9/15/andean-woven-coca-bags

- Georg Anne. Rebranding Bolivia’s demonized, sacred coca plant.

- Historia en accion:La hoja de coca para el Peru.

- Marinete. Mitos sobre la coca. (waybackmachine)

- Museo de la coca. La Paz, Bolivia.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coca

- Usos de la Coca en Medicina Tradicional