Kuka, is Quechua and means unique, excellent and sacred, it’s the name of the coca plant and leaf. Khoka, the Aymara word means ‘the tree’. Discover the legends of Mama Coca from Bolivia and Peru.

In this Article

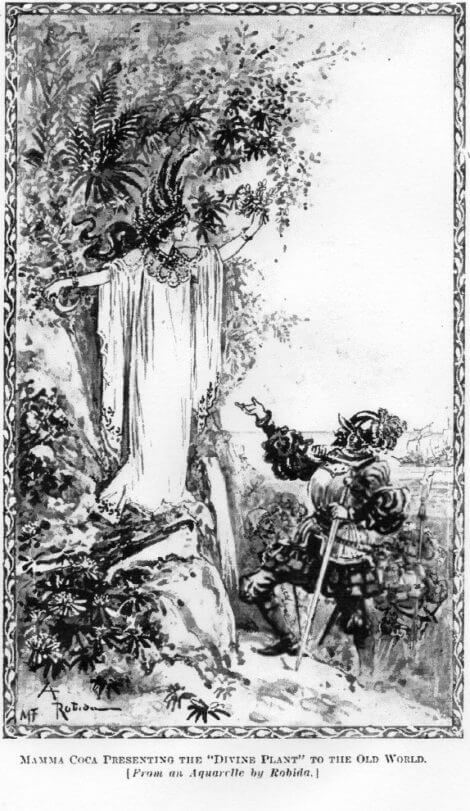

The discovery of mama coca, or Erythroxylum coca or Erythroxylon novogranatense, was ever a story of many dimensions, and the telling of the tale depended on the leafs use as medicine, food, drink or for sacred rites and rituals.

It has also been a vital part of the cosmology of the Andean peoples of Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Colombia, Brazil, northern Argentina and Chile from the Pre-Inca period through to the present. Coca leaves play a crucial part in offerings to

- Apus (mountains),

- Inti (the sun), or

- Pachamama (the earth).

The sacred leaf was intimately related to other deities, Achachilas, Mama Quilla, Manco Capac and his sister-wife Mama Oello, demi gods, and mortals.

The legends of Mama Coca

The founding myth of the Peruvian Inca empire itself was related to coca. Garcilaso de la Vega, when recounting the legend of the children of the sun who founded the empire, pointed out that they had offered coca leaves and taught the people that they could be used to kill hunger, eliminate fatigue and allow the unfortunate to forget their misfortunes.

Khuno and Mama Coca

One origin of the word “coca” has been found in the Aymara word Khoka, which simply means the tree. However, the significance of this word is both magical-religious and social.

Its mythical origin establishes that Khuno, God of snow and storms, would set fire to large areas of the mountains in order to fertilize the land for his inhabitants, however, the difficult proliferation of fires angered Khuno so much that he decided to unleash a fire storm, leaving the fields exhausted and its inhabitants left to their own fate.

When they came out of their caves once the fearsome storm had passed, the only thing they found as a food source was a small bush with bright green leaves whose ingestion immediately produced a feeling of well-being, thus saving them from the devastation produced by Khuno’s fury. The leaf was therefore assimilated as a divinity and from then on named “Mama Coca”.

Mama coca embodied the powers of nature and the cosmos, she was huaca (sacred) and therefore the leaf itself was magical. Her powers derived not only from her tempestuous appearance, but as a universal mother she was, above all, the “Earth Goddess” or Pachamama.

Cocas sacrifice

This is the story we learned visiting the coca museum in La Paz, Bolivia:

Cómo la coca llegó a los Incas

Cómo la coca llegó a los Incas

Coca era una joven india con una extrema belleza, que causaba envidiada a todas las regiones del imperio de Kollasuyo. Todos los hombres se derretían delante del encanto de la joven mujer, y Coca se complacía a este juego de seducción devastador. Si unos no podían evitar de soñar con Coca, los otros desarrollaban celos y rivalidad, lo cual ponía seriamente en peligro la cohesión y estabilidad del país.

El Inca estaba consciente del problema que representaba Coca, y decidió consultar al consejo de sabios. Estos se retiraron para observar a los astros y leer en las entrañas de la llama y concluyeron que la salvación del imperio pasaba por el sacrificio de Coca. El Inca, contra su voluntad, ordenó entonces la muerte de la joven mujer y que los restos sean enterrados en los jardines de sus pretendientes. El tiempo pasa, y en cada lugar donde los restos de Coca habían sido enterrados empiezan a crecer pequeños arbustos con hojas verdes ovaladas y lisas que le llamaron Coca, en homenaje a la joven mujer.

How the Coca plant came to the Incas

How the Coca plant came to the Incas

Coca was a young Indian woman who was famous in all the Kollasuyo Empire for her extreme beauty. No man could resist the charm of the young woman, and Coca was taking pleasure in this devastating seduction game. Some could not help dreaming of Coca, the others developed jealousy and the competition seriously put in danger the cohesion and stability of the country.

The Inca was aware of the troubles caused by Coca, and decided to consult the council of the Wise. After observing the stars and reading in the entrails of a llama, the Wise concluded that Coca’s sacrifice was necessary for saving the empire.

Although not in favor of such decision, the Inca sentenced the young woman to death and requested that parts of her body would be buried in the gardens of all her lovers. Time goes by, and in each place where Coca’s remains had been buried, small bushes with oval and smooth green leaves started to grow. These little bushes were called coca, in homage to the young woman.

Public domain, edited.

Andean coca prophecy

The coca leaf represents for the natives; strength, life, it is a spiritual food that allows them to enter into contact with their divinities

“Apus, Achachilas, Inti, Mama Quilla, Pachamama”.

While for its enemies coca is a cause of madness and dependence… “

La hoja de coca representa para los indígenas; la fuerza, la vida, es un alimento espiritual que les permite entrar en contacto con sus divinidades “Apus, Achachilas, Inti, Mama Quilla, Pachamama”. Mientras que para sus enemigos, la coca es una causa de locura y de dependencia…” (Profecía Andina)

Mama Coca or Cocamama was not meant to be cooked up with chemicals…

Coca is not cocaine. Coca provides health benefits over and beyond basic nutrients, it is medicine, sustenance, coca is fundamentally cultural.

NOTA BENE:

The cultivation, sale, and possession of unprocessed Coca leaf is generally legal in Bolivia, Peru, Chile and Argentina – where traditional use, like Chewing of coca, is established, although cultivation is restricted.

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- Museo de la coca. La Paz, Bolivia.

- Terrazas Orellana Carlos. La milenaria y sagrada hoja de coca.

- Vacchelli Sicheri Gian Franco. La hoja de coca en la cosmovisión andina.

- Villamil Antonio Diaz. Leyendas de mi tierra. 1929. Rewritten by N. Brachet.

- Wikipedia: Coca.

- Wikimedia Commons: Benzoylmethylecgonine, the psychoactive constituent of coca, by Nuklear (own work).