Southamericans chew coca leaves to eradicate hunger, thirst, improve muscle stamina, to counter altitude sickness and oxygen deprivation. The leaf is also used in teas (or mate de coca), in cooking and for religious ceremonies. Discover the curative use of Coca for the Andean communities.

In this Article

Erythroxylum coca

Family: Erythroxylaceae

Species of coca trees:

Erythroxylum coca (Andean coca – Bolivian or Huánuco Coca)

Erythroxylum coca ipadu (Amazonian Coca)

Erythroxylum novogranatense (Colombian Coca)

Trujillo Coca, Erythroxylum novogranatense var. truxillense (Peruvian Coca)

Aymara: Khoka (the tree)

Quechua: kuka or quqa (the tree)

Venezuela/Colombia: Hayo, Ayu (coca crop)

Spanish: ocha de coca

English: coca leaf

Coca leaves are nutritious and full of vitamins, of the type C, E, B1 and B2. They also contain minerals such as calcium, potassium, barium, copper and magnesium.

Apart from this minerals and vitamins, the leaves contain fibers, essential oils (flavor/aroma) and a number (up to 15) of alkaloids in varying amounts, such as hygrine, cuscohygrine, cis- and trans– cinnamoylocaine, nicotine, methylecgomine, tropococaine, tropinone, benzoylecgonine, and cocaine.

This alkaloids – one of which, is cocaine, that has gained notoriety as a narcotic – are leading to the mistaken idea that coca equals cocaine. The white powder is the isolated illegally manufactured purified drug, cocaine hydrochloride.

Coca is not cocaine.

Coca is medicine, food and drink.

For the Andean communities Coca leaves are fundamentally cultural.

Coca is highly useful for its antibacterial and analgesic properties, in addition to aiding in digestion and in preventing constipation.

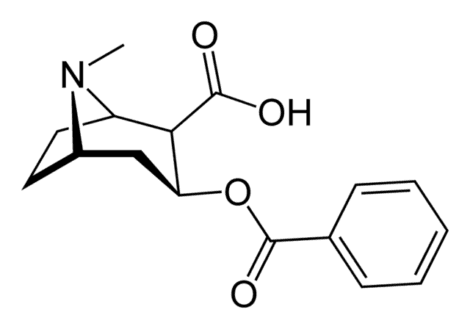

Benzoylmethylecgonine

Benzoylmethylecgonine (L-Cocaine) is an alkaloid ester in coca leaves.

Research has indicated that Benzoylmethylecgonine can affect aspects of brain function and stimulates certain portions of the autonomic nervous system.

It might produce:

- increased wakefulness,

- increased focus, and

- better general body coordination.

Dried coca leaves contain between 0.23% to 0.96% of Benzoylmethylecgonine. Only the dose makes the poison, as Paracelsus said: ‘Sola dosis facit venenum’.

However, the amount of cocaine absorbed through chewing is very small, it has been suggested that the stimulating effect may be exerted by flavonoids contained within the leaves. Further research is being carried out into these compounds.

Cocoa is sacred in the Andes and it is also the source of the alkaloid cocaine – an insecticide and local anesthetic that has had the largest impact in Western Medicine of any Neotropical phytochemical.

Coca distribution in the central Andes

The shrub plays a significant role in traditional Andean culture. Coca is a plant in the family Erythroxylaceae, native to north-western South America. The two species cultivated in South America are E. coca (Andean coca – Bolivian or Huánuco Coca) and E. novogratense (Colombian Coca).

Each have two variations adapted to different topography, soil conditions and climate, like Erythroxylum coca ipadu (Amazonian Coca) and Trujillo Coca, Erythroxylum novogranatense var. truxillense (Peruvian Coca).

The best conditions are found in the subtropical valleys on the Andean Amazon slopes. Coca monoculture degrades soils, and causes landslides and loss of biodiversity.

The eastern slopes of the Andes in Peru and Bolivia, where hundreds of steep terraces climb the mountainsides as high as 2.000 meters or 6561.68 ft, are the main coca-growing areas. But much of the upper Amazon is dotted with plantations; some stretch across the lowland plains, others are hidden in the forest.

Coca chewing culture

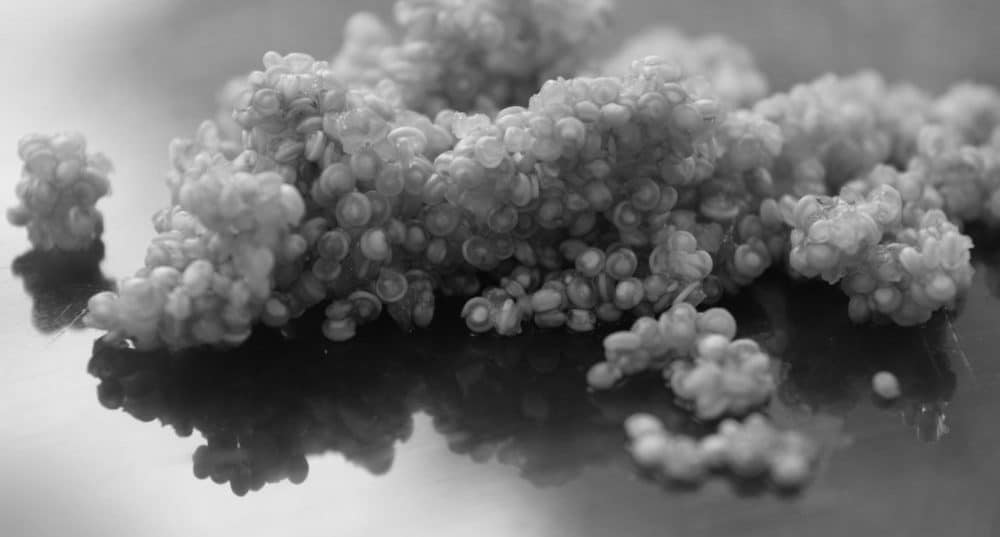

The leaves are gathered and dried in the sun and then chewed with lime. The fresh, uncurled, dried leaves, are a deep green color on the upper surface, and a grey-green on the lower surface, and have a strong tea-like aroma.

When chewed, they produce a numbness in the mouth, and have a pleasant, pungent taste. Older leaves have a camphoraceous smell, a brownish color, and lack that pungent taste.

Public domain, edited.

Chewing coca leaves is most common in indigenous communities across the central Andean region, particularly in the mountains of Argentina, Colombia, Bolivia, and Peru, where the cultivation and consumption of coca is a part of the national culture, similar to chicha, a drink made from fermented maize, quinoa or fruit.

It also serves as a powerful symbol of indigenous cultural and religious identity, among a diversity of indigenous nations throughout South America.

Archaeological evidence has shown, that Coca chewing is 8000 years old – a deeply rooted economic, social and religious tradition in the Andes.

Since ancient times, its leaves have been an important trade commodity between the lowlands, where it is chiefly cultivated, and the higher altitudes, where it is widely consumed.

Traces of coca have been found in archaeological evidence dating back 6000 to 8000 years, with mummies discovered buried with a supply of coca leaves, along with pottery decorated with depictions of figures displaying the characteristic cheek bulge of the coca chewer.

The local communities chew the leaves to eradicate hunger, improve muscle stamina, to counter motion sickness and oxygen deprivation. The Inca used coca leaves for divining, barter, sacrifice, and chewed them.

The leaves will thin the blood to help with the fatigue and headache caused by living at high altitudes. They relieve hunger and thirst and for some, the stimulating effect can be compared to drinking a cup of espresso.

How to chew coca leaves

The chewing of coca is a well-defined practice that has changed little over the centuries.

It is called acullico, pijcheo

(Peru, Bolivia), mambeo (Colombia), mastico, or coqueo.

First, the coquero takes several coca leaves from a chuspa, a bag like container.

It is considered good manners to perform a pukuy (‘blow a kintu’) before putting the coca leaves in the mouth.

The midribs of the leaves are removed and placed in the side of the mouth.

More leaves are added until a quid or plug is formed.

From a poporo, a small container carried in or attached to the chuspa, a limestone substance (llipta or bi carb soda) is taken and added to the quid in the mouth.

It is called “coca chewing” when in fact, it’s coca sucking.

The traditional way is to hold the leaves on the right or left side of the cheeks. Allowing the dry leaves to absorb the saliva for the next few minutes. As the saliva permeates and extracts the chemical compounds of the leaf, it turns a rich green color.

The mouth will become numb within 10 minutes a sign, that the coca leaves are showing effect. Bitterness characterizes the early stages of chewing, this being the taste of the many alkaloids in the leaf. The juice of the coca leaf then has a distinctive grassy flavor, like green tea leaves, that most describe as pleasant.

A single quid, the size of which is variable and may be augmented as the leaves are exhausted, will be chewed for 30 to 90 minutes. Regular chewers consume about 25-75 grams of leaves per day.

The chewing of a cocada is a measure of time indicating 45 min of walking comfortably for 2 km of steep terrain or 3 km of level grounds.

Some believe, that coca tastes bitter if some misfortune is brewing.

“Social coca”: The ritual of sharing coca leaves

In, “The Hold Life Has: Coca and Cultural Identity in an Andean Community”, Allen Catherine notes:

“Chewing coca is ritualized, for example, in Quechua communities around Cusco, before chewing coca it is customary to select three perfect leaves from your bag, array them between your thumb and forefinger, and blow gently across them as an offering of the breath of life to Pachamama in gratitude for her generosity.

This is then passed to the person you are inviting to chew with you. It is common courtesy to offer guests some leaves to chew and it is proper to receive them with both hands open together.

Such regular devotional acts help weave the web of reciprocity that connects humans with the sacred places of their divine geography and with the legacy of their ancestors.”

In, “The Botanical Science and Cultural Value of Coca Leaf in South America”, Caroline Conzelman and Dawson White, note:

“Coca is commonly used during community meetings and celebrations in rural villages and urban barrios, and at mass gatherings such as festivals or forums. When chewed collectively, coca inspires communication and the alliance of the group.”

As anthropologist Enrique Mayer observed in Quechua community meetings in highland Peru:

” Coca serves the additional purpose of sharpening the senses, permitting concentration, and, when consumed with care, creating a sense of internal peace and tranquility that is indispensable for intellectual work.”

Chuspa or huallqepo, the coca leaf bag

Men carried the handful of coca leaves that they took with them to their daily work in specially made pouches, chuspa (Quechua for bag). In Aymara, another widely spoken Andean language, they are called, huallqepos .

The ancient Inca state regulated textiles as a critical aspect of the economy, religion, and imperial ideology. They used textiles and fiber as a means of communication through structure and iconography, expressing status symbols.

Coca bags would also carry meaning as they were reserved for members of the elite. At the same time, specific patterns, fibers, and styles indicated the status and profession of the person wearing it. For example, an additional fringe added to the bottom of the back marked higher status, such as royalty.

Coca bags were created by weaving a single piece of cloth, then doubling it over and sewing up the sides, and sometimes, adding a strap so that it could be carried across the body.

In 1609 Bernabe Cobo wrote that,

“underneath his mantle and over his tunic a man would carry ‘a small chuspa which hangs around the neck. It is more or less one span in length and about the same width.

This bag hangs down by the waist under the right arm, and the strap from which it hangs passes over the left shoulder.”

This required forethought by the weaver, since the figures on each side of the bag would need to be oriented differently to make it legible when completed.

This double cloth pouches are a characteristic artifact of Pre-Columbian Peru and important symbols of social identity and a display cultural affiliation. As part of this tradition, coca leaf bags show to the rest of their people how skilled they are in weaving.

Highland textiles are traditionally woven from the hair of native camelids, usually the domesticated alpacas and llamas, and more rarely, wild vicuña, guanaco or cotton.

Coca bags are still used in Andean culture today. On the Bolivian valleys of Lake Titicaca live the Callahuaya. They are indigenous herbalists, naturalists, and magical healers who travel throughout Argentina, Bolivia, Northern Chile, and Peru.

Their Chuspas, or coca leaf bags, are woven by their wives and constructed with traditional techniques and materials, like camelid fibers and dyes from local plants and insects.

We have seen both, locals carrying woven chuspas, as well, as simple plastic bags filled with coca leaves tucked to the belt or cap.

Lime and soda

Today, they are traditionally chewed with lime or some other reagent such as bicarbonate of soda to increase the release of the active ingredients from the leaf. The lime was made by burning quinoa stalks (called ilucta), bones, limestone, or sea shells.

Other names for this basifying substance are llipta in Peru and the Spanish word lejía, bleach in English. Also names like tocra or mambe are used, depending on its composition. Many of these materials are salty in flavor, but there are variations.

In La Paz of Bolivia it is known as lejía dulce (sweet lye), which is made from quinoa ashes mixed with aniseed and cane sugar, forming a soft black putty with a sweet and pleasing flavor. In other places, baking soda is used under the name bico.

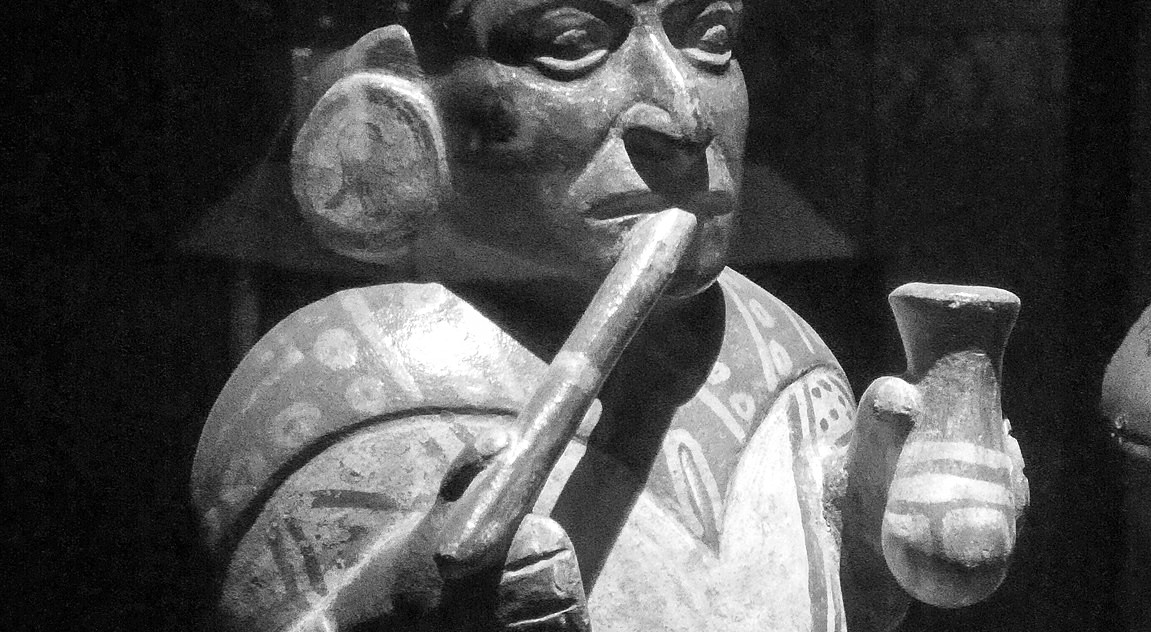

The poporo

In Colombia the powdered lime is traditionally carried in a separate vessel, called a poporo, apart from the woven bag for coca leaves. These poporos, which require the use of a dipstick, ‘palillo‘, to avoid chemical burns while adding the lime to the quid, are also the main evidence of ancient coca use from many archaeological sites in Ecuador and Colombia.

David Acevedo Monsalve, says: “The Poporos were devices that indigenous cultures would use to store small amounts of lime used in the sacred ritual of ‘mambeo,’ which consisted of chewing the coca leaf with lime.

To extract the lime from the receptacle, a metallic pin would be used.

The mambeo ritual implied a deep respect for the plant and it was considered to be a form of communication with the divine.

Warriors would carry their Poporos on their necks and would perform the mambeo in order to fight with strength.”

South Americans often use containers made of gourds instead of ones made of metal, a practice that continues into the present.

Poporos and other containers can play active roles in reproducing the world and the social relations within it. An example often cited is the use of poporos by Kogi communities in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta in northern Colombia. Young Kogi men receive a poporo when they become adults.

Reichel Dolmatoff, 1950, defines the poporo as a manifestation of female genitalia, and the ‘palillo‘ as male genitalia. Using the palillo to remove lime from the poporo is the practice of sexual intercourse. Kogi people also consider the larger gourds used as water containers “como útero y como ‘fruto’ de la Madre”, as a uterus and as the fruit of the Mother.

The Poporo is also seen as a symbol of duality and represents the cosmic balance of opposites. The bulk part of the poporo or the belly represents the feminine elements, “Pacha Mama” or Mother Earth, while the neck symbolizes the masculine elements.

In the mambeo ritual, the lime is extracted using a metallic pin, which represents the moment the skies join together with the earth and breathe life to all creation.

Some poporos also may serve as funerary vessels and contain cremated human remains

Ethnomedicine of coca

Ethnomedicine is the study of traditional medicines derived from indigenous or traditional knowledge of a community.

Coca has been cultivated for over 8000 years and is a culturally significant pharmaceutical plant in South America.

Curative reasons to chew coca leaves

The use of the coca plant not only preserves the health of all who use it, but prolongs life to a very great old age and enables the coca eaters to perform prodigies of mental and physical labor.

John Pemberton, Atlanta Constitution, 1885.

Coca leaves have a long history of medicinal uses . Women in labor often chew the leaves to ease pain and to hasten the birth of the child. Over the centuries, coca has been used to relieve a wide assortment of aches and pains, as a laxative, as an aphrodisiac, and as a treatment for ulcers, asthma, and malaria.

Because coca constricts blood vessels, it’s also been used to treat nosebleeds and wounds.

Sucking the leaves or drinking coca infusion, acts as a mild stimulant that suppresses hunger, thirst, pain, and fatigue. Other benefits include muscle relaxation, which can help with menstrual cramps.

Coca leaf tea is taken to combat stomach pain, intestinal spasm, nausea, indigestion, and even constipation and diarrhea. It is essentially viewed as a comprehensive remedy that restores balance to the digestive system.

Coca is masticated or held in the mouth for relief of painful oral sores and also to aid in the healing of oral lesions. Similarly, this plant is used for toothaches as well.

They also help to treat altitude sickness by opening up the respiratory tract and relieving the feeling of shortness of breath and tightness in the chest.

The first European description of coca is from Amerigo Vespucci from 1499; he described how South American aborigines would chew the leaves to overcome fatigue and hunger.

In 1609, Padre Blas Valera wrote:

“Coca protects the body from many ailments, and our doctors use it in powdered form to reduce the swelling of wounds, to strengthen broken bones, to expel cold from the body or prevent it from entering, and to cure rotten wounds or sores that are full of maggots.

And if it does so much for outward ailments, will not its singular virtue have even greater effect in the entrails of those who eat it?”

Coca leaves are nutritious

They contain vitamins C, E, B1 and B2 and minerals such as calcium, potassium, barium, copper and magnesium. Coca powder is used in recipes like in bread, butter, ice cream and candies. Gastón Acurio, owner of Astrid & Gaston Restaurant, one of the finest chefs in Peru, has coca cocktails on his menu.

Coca chewing is a stimulant

The leaves are similarly stimulating as coffee does, and can help to stave off drowsiness. It also acts as an appetite suppressant, wards of thirst, hunger, and tiredness.

“The Indians made a quid of leaves and lime about the size of a walnut and held it in their cheek, swallowing only the juice.

The amount of cocaine liberated from a quid is minute and its only effect is to dull the senses slightly, making the chewer less hungry, thirsty, and tired. Coca chewing was believed to be very good for the teeth.”

Cobo, 1890-95, bk. 5, ch. 29

Coca chewing decreases hunger

Coca chewing is thought to decrease the feeling of hunger. Further investigation of this phenomenon has discovered that coca has effects on glucose homeostasis. Chewing coca leaves has been found to elevate blood glucose above the fasting level. This finding of elevated glucose after coca chewing also lends scientific credibility to the belief that coca staves off hunger pains.

Coca chewing acts as an anesthetic

Chewing coca leaves will leave an anesthetic feeling in the mouth, down the throat affecting the tongue. In order to possibly relieve tooth and headaches, the pain of minor injuries, Arthritis and back pain.

Mate de Coca: Coca tea and acute altitude mountain sickness (AMS)

Chewing coca leaves helps cope with altitude sickness. Irmgard Bauer states :

“Virtually all travellers to the Andes will come across coca leaves and coca tea. The tea is served in eateries, trains and accommodations from the very basic to the most luxurious. People picking up arrivals at high altitude airports typically come armed with a hot thermos of coca tea to prevent acute altitude mountain sickness, soroche (AMS).

Coca tea may come as a few hard, dry leaves in hot water looking pretty but doing little, or as commercially available teabags which, the leaves being chopped up, color the hot water quickly; the slightly bitter taste is apparent, and an effect noticeable. Even better would be the chewing of the leaves though this is less popular with travellers.

Some fanciful application in biscuits, ice cream or lollies have no effect. For many travelers, drinking coca tea is normal, others, due to ignorance, may feel like criminals. For some it may be an exciting challenge, others understand coca as part of a cultural discourse with the local people.”

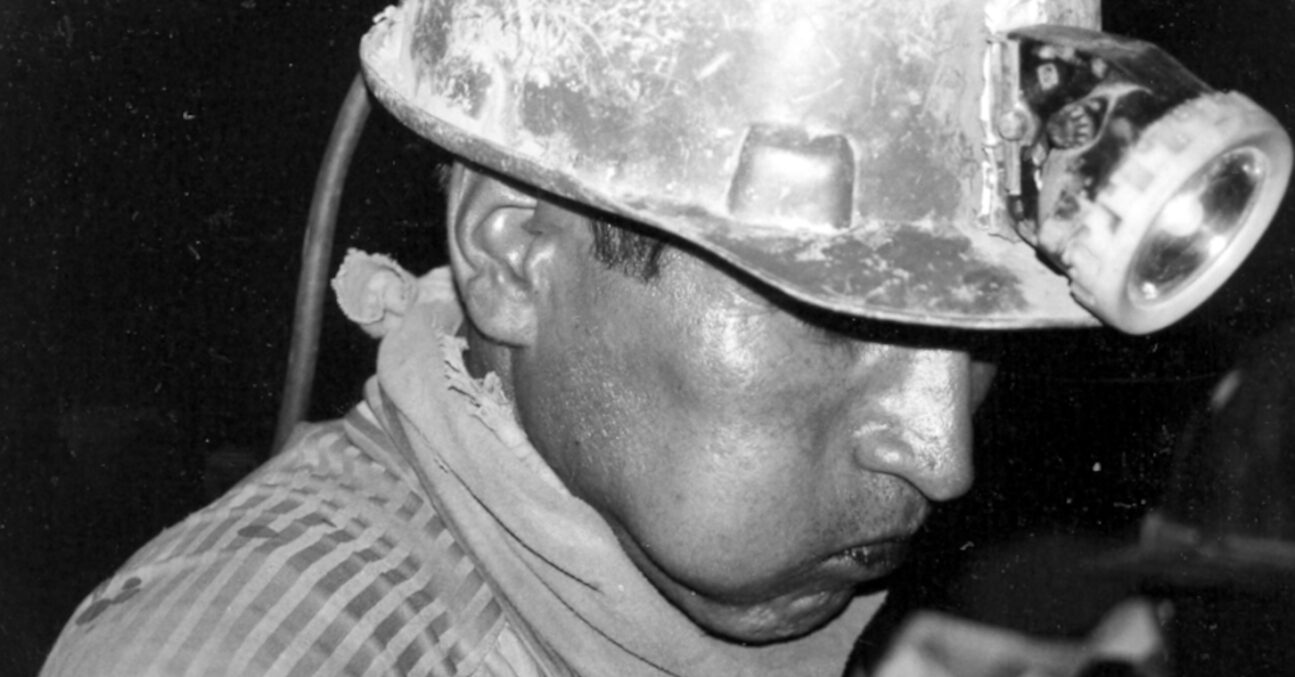

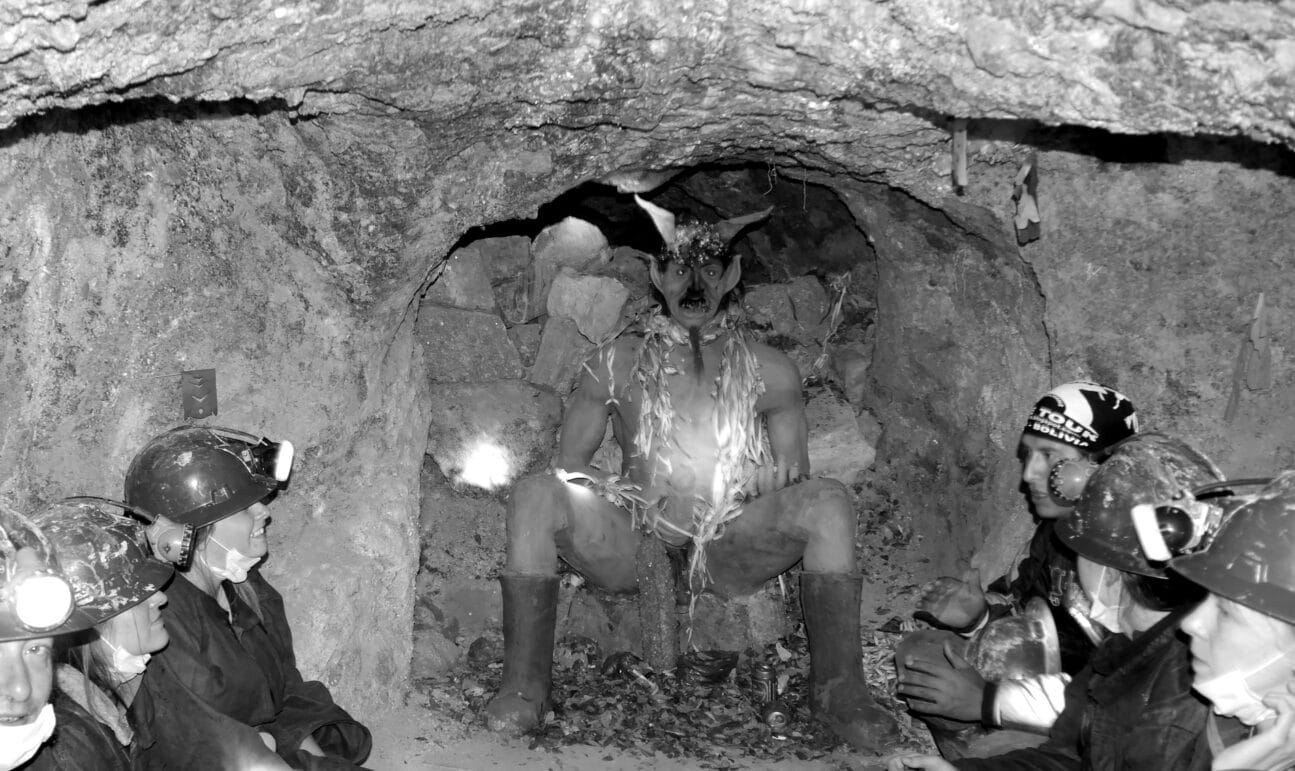

In Bolivia we purchased coca and dynamite, fuses, alcohol and cigarettes as gifts for the miners to use and to offer to El Tío (the devil) for protection.

Other uses of coca leaf infusion

The infusion of eight Coca leaves can ease stomach cramps, stomach pains, the digestive tract, indigestion or indigestion and diarrhea, melancholy, nerve problems, diarrhea and dysentery. A decoction is used for conjunctivitis.

Eight leaves of Coca and two mint leafs can help against nausea and vomiting.

10 burned Coca leaves, a piece of avocado (finger sized) and a spoonful of rice is traditionally used as a remedy for dysentery.

An infusion of 20 coca leaves to a pot of boiling water with the juice of half a lemon and half a teaspoon of salt can help with inflammation of the tonsils and throat – gargle before each meal.

Some limitations must be considered. More studies are required to elucidate the mechanisms exerted by coca extracts and compounds. Also pre-clinical and randomized clinical trials, are needed to better understand the beneficial effects of the plant extracts and compounds on human health.

Note: This post does not contain medical advice.

Please ask a health practitioner before trying therapeutic products new to you.

If you do wish to experiment, we suggest doing further research.

~ ○ ~

Decriminalizing chewing coca leaves

In its annual report, the U.N.’s International Narcotics Control Board said the two Andean governments of Peru and Bolivia should

“abolish or prohibit activities … such as coca leaf chewing and the manufacture of coca tea.”

In its natural form, the leaf is used by millions of people in Peru and Bolivia, in teas, in cooking and for religious ceremonies and ritual offering to the gods, often in supplication for the souls of deceased loved ones.

Coca is also the raw ingredient of cocaine, but Coca is not cocaine. Coca is medicine, sustenance, coca is fundamentally cultural.

On a trip to Bolivia in 2015, Pope Francis asked to chew coca leaves after being offered coca tea. While coca leaves were banned under the 1961 UN Convention on Narcotic Drugs, it can be grown for medicinal and religious use with a license obtained from the government.

The indigenous people of Bolivia believe the coca plant is sacred. They declared its leaves a ‘cultural patrimony’ in the Bolivian constitution in 2009.

Bolivian President, Evo Morales, once a coca grower, campaigns for decriminalizing chewing coca leaves. For many years, South America’s indigenous people understood the effects of the coca plant, it enhances their daily lives living at high altitudes.

These days while traveling through Bolivia, Peru, Chile and Argentina, guests can do the same.

The 19th-century American coca enthusiast W.G. Mortimer epitomized the appeal of coca in one word: endurance.

While traveling through Bolivia, Peru, Chile and Argentina we drank coca tea against altitude sickness and used the leaves during hikes in the Andes in order to gain stamina and quench thirst. Chewing coca can be compared to drinking a cup of espresso.

NOTA BENE:

The cultivation, sale, and possession of unprocessed Coca leaf is generally legal in Bolivia, Peru, Chile and Argentina – where traditional use, like Chewing of coca, is established, although cultivation is restricted.

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- https://www.tni.org/en/primer/coca-leaf-myths-and-reality

- LA MILENARIA Y SAGRADA PLANTA DE LOS INCAS

- https://www.monah.org/artifact-blog/2020/9/15/andean-woven-coca-bags

- Reichel Dolmatoff Gerardo. Los Kogi: Una tribu de la Sierra Nevada, en Colombia. Vol. 1. Bogotá: Editorial Iqueima, 1950.

- https://artsandculture.google.com/story/eQXh1XY0ET32Lg

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303315045_The_Botanical_Science_and_Cultural_Value_of_Coca_Leaf_in_South_America

- Allen Catherine J.The Hold Life Has: Coca and Cultural Identity in an Andean Community. 2002.

- Georg Anne. Rebranding Bolivia’s demonized, sacred coca plant.

- Travel medicine, coca and cocaine: demystifying and rehabilitating Erythroxylum – a comprehensive review

- Historia en accion:La hoja de coca para el Peru.

- Marinete. Mitos sobre la coca. (waybackmachine)

- Museo de la coca. La Paz, Bolivia.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coca

- Usos de la Coca en Medicina Tradicional