Deep in the depths of a lake in Scotland called Loch Ness, lives a mystery. It is a creature that hundreds of people claim to have seen. Some believe it’s a large dinosaur-like creature with a long neck and flippers, a gigantic snake, or a dragon.

Others imagine it is simply a large catfish or even some fallen branches from the nearby forest. Discover Myth and Folklore of the Monster of Loch Ness – the creature, whether it exists or not, has been a legend for hundreds of years.

In this Article

Loch Ness

Loch Ness is a 23 mile or 37 km long freshwater lake which lies along the Great Glen in the Highlands of Scotland. The fault dates from when Europe and America together formed the super-continent Pangaea, 400 million years ago.

As the continents began to break up and cluster around the north pole, Scotland was still in the grip of the ice twelve thousand years ago, but the main advances were over and the land was beginning to rebound from being depressed into the mantle. The surface of Loch Ness would have been at a similar elevation to sea level. A long geological fault that continues across Ireland and the North Atlantic to North America remains. Occasional earth tremors have still been observed over the last couple of centuries. This U-shaped valley, is home to the black waters of Lake Ness and a string of lesser lochs [lakes] along the way: Oich, Lochy and Linnhe nestled in a dramatic mountain scenery.

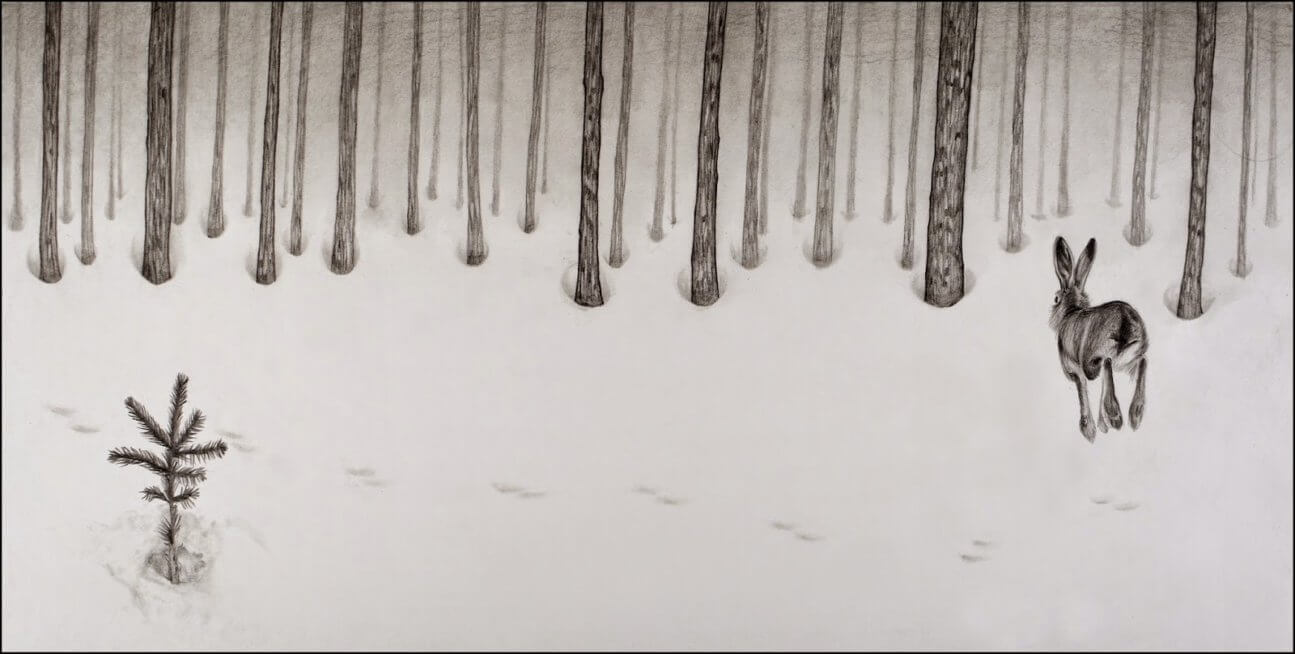

St. Columba defeating a monster on the banks of the River Ness

In the seventh century when Adomnán, ninth abbot of Iona, wrote the Life of St. Columba, the monster has its first appearance. Since Columba died in 597 AD, the accounts were written nearly a hundred years later. The tale of the first sighting of the water beast at the River Ness:

Concerning a certain water beast driven away by the power of the blessed man’s prayer.

Also at another time, when the blessed man was for a lumber of days in the province of the Picts, he had to cross the river Nes [Ness]. When lie reached its bank, he saw a poor fellow being buried by other inhabitants; and the buriers said that, while swimming not long before, he had been seized and most savagely bitten by a water beast.

Some men, going to his rescue in a wooden boat, though too late, had put out hooks and caught hold of his wretched corpse. When the blessed man heard this, he ordered notwithstanding that one of his companions should swim out and bring back to him, by sailing, a boat that stood on the opposite bank.

Hearing this order of the holy and memorable man, Lugne mocu-Min obeyed without delay, and putting off his clothes, excepting his tunic, plunged into the water.

But the monster, whose appetite had earlier been not so much sated as whetted for prey, lurked in the depth of the river. Feeling the water above disturbed by Lugne’s swimming, it suddenly swam up to the surface, and with gaping mouth and with great roaring rushed towards the man swimming in the middle of the stream.

While all that were there, barbarians and even the brothers, were struck down with extreme terror, the blessed man, who was watching, raised his holy hand and drew the saving sign of the cross in the empty air; and then, invoking the name of God, he commanded the savage beast, and said:

“You will go no further. Do not touch the man; turn back speedily”.

Then, hearing this command of the saint, the beast, as if pulled back with ropes, fled terrified in swift retreat; although it had before approached so close to Lugne as he swam that there was no more than the length of one short pole between man and beast.

Then seeing that the beast had withdrawn and that their fellow- soldier Lugne had returned to them unharmed and safe, in the boat, the brothers with great amazement glorified God in the blessed man.

And also the pagan barbarians who were there at the time, impelled by the magnitude of this miracle that they themselves had seen, magnified the God of the Christians.”

THE ART OF THE PICTS

The “pagan barbarians” who were there at the time, and witnessed the “wonder” of St. Columba most probably did not convert to the God of the Christians but possibly got to see Nessie long before St. Columba visited.

They were fierce hill tribes in what is now Scotland, and called Picts or “The Painted People” for they were known to love bright body art and multi- colored clothing.

Artists and prolific carvers of stone they leave us standing stones in the region around Loch Ness, we can see that the Picts were fascinated by animals, carefully etching them into the surface of the stone. Most of the animals depicted on the Pictish stones are lifelike and easily recognizable — all but some.

This carvings made some 1.500 years ago, could be the earliest evidence that Loch Ness harbors a strange aquatic creature.

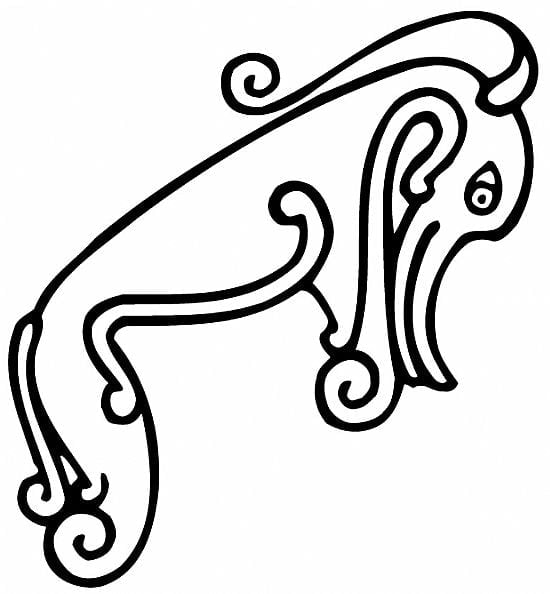

The Pictish beast

The strange creature has an elongated beak or muzzle, a head locket or spout, and flippers instead of feet.

Described by some scholars as a swimming elephant, the Pictish beast could also be the earliest known evidence for an idea that has held sway in the Scottish Highlands for at least 1,500 years that Loch Ness is home to a mysterious aquatic animal

— The Loch Ness Monster.

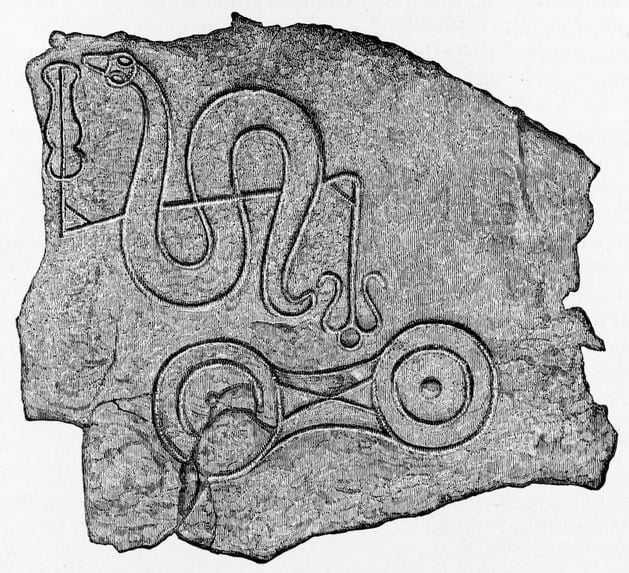

The Ancient Serpent Stone of Loch Ness

This carving, believed to be neolithic in origin, was found at Balmacaan House, which used to be near Loch Ness until it was knocked down in the 1930s.

It has been speculated that the serpent-like form my be some reference to the animals in and around Loch Ness.

The mystery of this stones resides in the little known ways and customs of the Pictish people.

There may be other symbols that equate to creatures the Picts regarded as aquatic and monstrous, such as those on the Serpent Stone, the Aberlemno II stone and the Pictish Beast. To these we must look for clues as to the monster lore of these highlanders.

They may mean something — or they may mean nothing at all.

WALTER OF BINGHAM’s Journey Through Scotland

Walter of Bingham (d. c. 1197) was a minor cleric from Nottinghamshire who, unable to fulfill his vow to go on the Third Crusade, made a pilgrimage to the holy sites of Scotland. William’s own manuscript of Itinerarium Scotiae (The Journey Through Scotland) has been long neglected , but shows the author’s fascination with Scottish history, customs and wildlife.

Walter of Bingham encounter with Nessie came one summer evening, as he approached the banks of the River Ness. Seeking safe passage across the river, he asked a group of fishermen mending their nets, but they rejected his request with terror in their eyes. Next, walking downstream, Walter encountered a young boy dragging his coracle along the shore. Hesitating at first, the boy agreed to row Walter of Bingham across in return for a silver coin.

They crossed without mishap, much to Walter’s displeasure, for he was self-confessedly thrifty; but as he watched the coracle heading back to the other shore, a great beast with fire sparking from its eyes suddenly erupted from below the waters, uttered an almighty roar, and then dragged the coracle and its unhappy occupant beneath the waves.

This is the first occasion that Nessie has received plausible identification as a giant bear: perhaps a relict population of bears survived in the vicinity of Loch Ness for many years, giving rise to the legend which surrounds it.

NISEAG: A Water Horse, Water Bull or Kelpie?

Around the world there are reputed to be creatures in many bodies of fresh water. An Niseag (the old Gaelic for Nessie pronounced “An Nee-Shack”) for the people of Scotland was a real creature hidden under the various layers of folkloric accretions.

In Scottish folklore, water, from small streams to the largest lakes are labeled Loch-na-Beistie – the loch of the beast.

The creatures are under water, lurking with ravenous intent, waiting for darkness in the long Northern nights before they come forth and devour the Innocent.

Nessie in Loch Ness, Morag in Loch Morar, Shielagh in Loch Shiel, Lizzy in Loch Lochy, Champ in Lake Champlain, Ogopogo in Lake Okanagan and, quaintly, Wally in Lake Wallowa and there is more.

These water creatures, like:

- horses,

- bulls and

- kelpies,

are said to have magical powers and malevolent intentions.

NB: Some authors regard the kelpie as being synonymous with the water-horse. The name was bestowed originally on the kelpie which allegedly resembled the horse-like hippo campus of classical myth and antiquity. The confusion can be cleared by the fact that the water-horse haunts only lakes – lochs and never rivers, whereas the kelpie inhabits torrents, waterfalls, and fjords. The water – bull however lives in moors and is said to be less malevolent then the kelpies. There are a number of regional variations of the water-horse and the kelpie and similar mythological creatures.

Tim Dinsdale‘s Project Water Horse was a study of pre- 1933 Highland folklore references to kelpies, water horses and water bulls indicated that Ness was the lake most frequently cited.

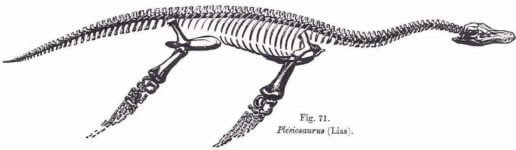

In 1980 a Swedish naturalist and author Bengt Sjögren wrote that present beliefs in lake monsters such as the Loch Ness Monster are associated with kelpie legends. According to Sjögren, accounts of loch monsters have changed over time; originally describing horse-like creatures, they were intended to keep children away from the loch. Sjögren wrote that the kelpie legends have developed into descriptions reflecting a modern awareness of plesiosaurs. [a marine reptile that lived 160 million years ago]

The Water Horse

In the Scottish highlands the water-horse, or Each Uisge, is a supernatural water spirit of mythology and folklore. There is a tradition of water horses in some sixty of the thousands of lochans and lochs of Scotland. The mythical water-horse is also known as the Capaill Uisce or the Manx Cabyll-ushtey, the Ceffyl dwr in Wales. It is one considered opinion that such mythical creatures appear in Scottish tales because

“…the fierceness of the sea is characterized as a powerful and preternatural hage whose form…

embody aspects of a stormy sea.” ,

the female are described as the Muileartach.

According to one version of the legend, the water-horse lures small children into the water by offering them rides on its back. Once the children are aboard, their hands become stuck to the beast and they are dragged to a watery death, their livers washing ashore the following day.

Each-Uisge

It is said, that Nessie’s origins may lie in the ancient Scottish myth of the loch- living water horse, the Each-Uisge, that lives in the sea and in lakes. It is a shape shifter disguised as a beautiful horse, a pony, a giant bird or as a handsome man.

Another variant tells:

As a horse it tricked unsuspecting victims to mount him, only to find that the melancholy horse dramatically increased size and power, and its mane turn to serpents which wound themselves around their victim. The great beast, so the story goes, would then gallop back into the loch where riders met their watery deaths.

Once the victim has drowned, the each-uisge rips the corpse apart and devours it, leaving only the liver to float to the surface. For this reason, people in the Highlands were often wary of lone animals and strangers they encountered near the water’s edge.

Folklorist Katharine Briggs described the “Ech-Ushkya” as “perhaps the fiercest and most dangerous of all the water-horses”.

The kelpie as a water horse in Loch Ness was mentioned in Aberdeen Weekly Journal, Wednesday, 11 June 1879:

“This kelpie had been in the habit of appearing as a beautiful black horse…

No sooner had the weary unsuspecting victim seated himself in the saddle than away darted the horse with more than the speed of the hurricane and plunged into the deepest part of Loch Ness, and the rider was never seen again.”

The Water Bull

The water bull, also known as tarbh uisge in Gaelic, is a mythological Scottish creature similar to the Manx tarroo ushtey. Generally regarded as a nocturnal resident of moorland lochs, it is usually more amiable than its equine counterpart the water horse, but has similar amphibious and shape shifting abilities.

The Kelpie

Robert Burns’ poem, ‘Address to the Devil’:

“…When thowes dissolve the snawy hoord

An’ float the jinglin’ icy boord

Then, water-kelpies haunt the foord

By your direction

And ‘nighted trav’llers are allur’d

To their destruction…”

The Scots word kelpie may be derived from the Gàidhlig calpa for “horse” or “cow”, or cailpeach, meaning “heifer” or “colt”.

There is a long tradition in Scotland of kelpies, malevolent shape-shifting creatures associated with running water and appearing as water horses or handsome young men. They may materialize as a beautiful young woman too, hoping to lure men to their death.

Kelpies can also use their magical powers to summon up a flood in order to sweep a traveller away to a watery grave.

LEGEND: The Kelpie of Loch Ness

In 1823, William Grant Stewart published a collection of “Scottish legends and superstitions” that he had gathered from talking to friends in that country… and his book happens to hold the only known tale of the well-known Scottish water monster called an ‘Ech Uisque’ [Water-Horse], ‘Kelpie,’ or ‘Kelpy’ said to have inhabited the now-infamous Loch Ness.

Stewart collected the story from a man named Wellox. Mr. Wellox claimed that this tale had happened to one of his own ancestors, and that his family still had proof of the matter in hand.

In the time of Mr. Wellox’s ancestor James Macgrigor, the area of Loch Ness was being terrorized by the predations of a water-horse that would wander the roads near the Loch in the guise of a riding horse, fully equipped. When a foolish person chose to mount this animal, the kelpie would fly into the air and sink into either Loch Nadorb, Loch Spynie, or Loch Ness, to eat the victim at the monster’s leisure. Macgrigor, having heard of many of the attacks of this particular kelpie, came to desire a chance to meet the monster and end its predations. As it worked out, he got that chance.

One day as Macgrigor was traveling through the Slochd Muichd, a solitary pass on the road between Strathspey and Inverness, the Scotsman ran across a riding horse, fully decked out, quietly eating grass on the roadside. Macgrigor knew instantly that this must be the very beast he had heard so much about; and so he approached the horse as if to mount it… then drew his sword and struck the creature across the nose, almost dropping the animal right there and then. The stroke had cut through the creature’s bridal, and one of the bits from it fell at Macgrigor’s feet. The Scotsman, out of curiosity, picked up the bit as the kelpie gathered its wits, and he placed the bit in his pocket as he prepared to renew his battle with the monster.

But the creature did not attack back. Instead, it chastised the Scotsman and his behavior, pointing out that Macgrigor had no right or reason in attacking the kelpie as the kelpie had not attacked him. It stated that the Scotsman’s actions were both cruel and illegal, and that it would be justified in returning the attack two-fold; but the beast disliked such quarrels and therefore was willing to overlook the whole matter if Macgrigor peacefully returned the bit to it. Macgrigor replied with a very frank opinion of both the nature of the monster and of its occupation. Strangely, the kelpie took the abuse and then stated that it had no choice in its occupation as it was the only way a kelpie could make an ‘honest living’; and then it requested the bit from the bridle back again. It was now obvious that the kelpie’s non-violent behavior was based around one simple objective… it wanted the bridle bit back, very badly.

Macgrigor decided to see if he could find out why. The Scotsman told the kelpie that he would be inclined to return the bit to the beast, if the beast could satisfy his curiousity by giving him some account of the bit’s use and qualities. Eagerly the kelpy explained that the bit in the bridle was essentially a present from the Devil himself, and that the small object held all the miraculous qualities that allowed the kelpie to change shape, overpower foes, and to fool people in the way that its detestable occupation required. As a further fact, the kelpie would not survive twenty-four hours without the bit in its power, but it was avoiding conflict with Macgrigor for he could now utilize the very powers himself in a battle with the kelpie. In addition to all of that, looking through the hole in the bit would also allow a user ‘second sight’… the ability to see invisible beings and spirits in the world around.

Macgrigor had heard enough: he wasn’t going to return such a powerful object to such a monster. Naturally, the kelpie objected; but Macgrigor simply turned and started to walk home. All the long way the kelpie followed the Scotsman, telling him tales of the horrors it had unleashed on other humans that had dared such an affront against it, all quickly followed by insincere promises that it would in no way show such a disrespect to Macgrigor if he chose to return the bit to it instantly. Occasionally the kelpie forgot the Scotsman’s advantage… but a quick florish of Macgrigor’s sword and the kelpie immediately quieted down and began anew its attempts to convince the Scotsman to surrender the bit civilly.

When they came in sight of Macgrigor’s house, the kelpie’s state of mind became desperate; it’s need for that bridle bit in order to survive led it to run ahead of the Scotsman and to firmly position itself in front of the door to his house. The kelpie announced very simply that Macgrigor would never pass through his door while in possession of the bit, and the creature then prepared itself for the battle to come.

The kelpie, however, was too focused on its stative goal and stayed right in place blocking the door as Macgrigor walked to the back of his house. At a back window Macgrigor called his wife over to him, and then he tossed the magical bit of the kelpie’s bridle through the window to her. Having done this, the Scotsman walked back to the front of the house where the desperate monster awaited his attempt to get past it, and announced that the bit was now, in fact, within the structure.

The kelpie could not enter the house; a rowan wood cross was above the door, a sure block to all devilish creatures. Finding itself with no hope of changing its fate the broken beast walked away, spewing its most horrid opinions of the Scotsman James Macgrigor… and, as stated already,

Macgrigor’s family retained ownership of the kelpie’s bit at least until the time this tale was told to William Grant Stewart and then included in his book of Scottish folklore in 1823.

Sea Serpents and horses

In 1852, the Inverness Courier, reported that a large group of people gathered on the loch side armed with scythes, pitchforks and guns prepared to repel a couple of ‘sea serpents’ that had been observed swimming steadily towards them across the loch.

As the two creatures approached the shore, one elderly man exclaimed and put down his gun. Then two Highland ponies scrambled ashore, having swum from the opposite shore.

If local people can be deceived like this, then diving birds, otters, eels and swimming deer could all be responsible for sightings made by people unfamiliar with the surroundings. Furthermore, the newspaper referred to the legends of ‘kelpies’, or the phantom water horses that were generic to all Scottish bodies of water. These legends served a practical purpose of keeping children away from dangerous stretches of water and perhaps warning young women about the perils of handsome young men.

NESSIE

Sightings have been sporadic over the centuries, it wasn’t until the 1930s when a road was built that travelled along the large lake that sightings became more common. Since then Nessie has been seen many times but has never harmed anyone.

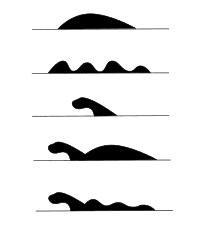

In 1934, this photograph of the Loch Ness Monster was published. It showed a long necked animal with a large hump lurking in the lake.

Anything living in the Loch today must have arrived from the freezing North Sea up the River Ness after the final retreat of ice. Nessie is reported to have an elongated neck that quite often protrudes from the water with a small head, diamond shaped flippers and humps on her back followed by a tail.

Some say that she lives under or around Urquhart Castle and many photographs (mostly fake) have been taken of her in the vicinity.

While research has been conducted at many of these lakes, Loch Ness is the icon for monsters and Nessie, the Loch Ness Monster is, without doubt, the star of them all. It is to Loch Ness where myriad researchers have flocked with their cameras and sonars, webcams and mini submarines, now even searching for DNA – their hopes, fears and dreams of solving the mystery of Nessie.

Despite all the reports, since 1960 researchers have been unable to prove the Loch Ness monster is real.

Many scientists and zoologists will admit to half- believing that a large aquatic animal does in fact exist in the Loch. There are numerous theories as to its identity, including a snake-like primitive whale known as a zeuglodon, a type of long-necked aquatic seal, giant eels, walruses, floating mats of plants, giant molluscs, otters, a “paraphysical” entity, mirages, diving birds and most popularly, a plesiosaur.

Nessie was even given a scientific name

“Nessiteras rhombopteryx”

named by Sir Peter Scott so that Nessie could be added to the British Register of officially protected wildlife.

The name, translated from Greek means “The wonder of Ness with the diamond shaped fin”.

Over the years many have noted that if you rearranged the letters of Nessiteras rhombopteryx, it can be made to read

“Monster hoax by Sir Peter S”.

Since the 1930s, when the legend gained currency, guest house- and pub-owners have been deeply grateful for the hordes of sightseers. Tourism has never stopped since then.

This was summarized by a headline from the Express on 24 April 1934:

‘Monster Bobs Up Again. Hotels Doing Fine.’

We could take a boat ride, visit the museum, the castle, buy souvenirs… taste whisky – Slainte mhath! Your very good health [pronounced ‘slange – ee-va’ – Scottish Toast]

The Loch Ness Monster may be there or not –

And one day you may get to see her yourself –

Slainte mhath Nessie

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- Adamnan. “Life of St. Columba.” Medieval Sourcebook. http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/columba-e.html

- AJS The Life of St Columba, St. Adomnan, Vita Sancti Columbae c. 690 AD. [By courtesy of Stadtbibliothek, Schaffliausen. Translations by Anderson and Anderson 1961] https://web.archive.org/web/20230416120155/https://www.lochnessproject.org/adrian_shine_archiveroom/papershtml/columba_loch_ness.htm

- Article Source:

- Columba encountered Loch Ness Monster. https://www.christianity.com/church/church-history/timeline/301-600/columba-encountered-loch-ness-monster-11629714.html

- Columba. Loch Ness. https://web.archive.org/web/20230416120155/https://www.lochnessproject.org/adrian_shine_archiveroom/papershtml/columba_loch_ness.htm

- Duffy Susanna.Nessie, the Beast of the Loch. https://web.archive.org/web/20050217034217/http://www.ezinearticles.com:80/?Nessie,-the-Beast-of-the-Loch&id=8678

- Entwined waterhorses, Aberlemno Churchyard Cross Slab (Aberlemno II) http://fionalang.blogspot.com/2014/05/aberlemno-sculptured-stones.html

- Haslam Garth. http://anomalyinfo.com

- https://celt.ucc.ie//published/T201040/index.html

- Kelpie Loch Ness. http://anomalyinfo.com/Stories/kelpie-loch-ness

- Kelpie Map of Scotland.

- Legend. Loch Ness. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/lochness/legend.html

- Loch Ness Monster Found at British Library. https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2013/03/loch-ness-monster-found-at-british-library.html

- Loch Ness Monster. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- Loch Ness. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/transcripts/2601lochness.html

- Loch Ness. Myths and Legends. https://www.visitinvernesslochness.com/explore-the-scottish-highlands/loch-ness-myths-and-legends/

- Nessie. https://www.scottisharchivesforschools.org/naturalScotland/Nessie.asp

- Project. Loch Ness https://web.archive.org/web/20221205005930/https://www.lochness.com/exhibition/loch-ness-project.aspx

- Riding the Seas: The Kelpies and Other Fascinating Water Horses in Myth and Legend.http://www.anynewsbd.com/riding-the.html

- Scotsman. St. Columba spotted the Loch Ness Monster. https://www.scotsman.com/lifestyle-2-15039/on-this-day-in-565-st-columba-spotted-the-loch-ness-monster-1-4209419

- Scottish Myths and Legends. https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/15583075.scottish-myths-and-legends-vampire-fairies-shape-shifting-selkies-and-the-loch-ness-monster/

- Stewart William Grant. The Popular Superstitions and Festive Amusements of the Highlanders of Scotland. https://books.google.co.in/books?id=f2UWAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=inauthor:%22William+Grant+Stewart%22&hl=en&sa=X&ei=AHOLU_3TD8uFogTAhYCQCg&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=water%20kelpies&f=false

- The Ancient Serpent Stone of Loch Ness. http://lochnessmystery.blogspot.com/2017/01/the-ancient-serpent-stone-of-loch-ness.html

- The Water-horse and the Kelpie

- Water bull. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- Watson Roland. The Water Horses of Loch Ness. 2011.

- Witchell Nicholas. The Loch Ness Story. 1974.