Discover cacao in Popol Vuh and the iconographic relationship between cacao and maize reflecting their importance within Maya cultures.

Before this, the cacao tree belonged to the realm of the Underworld lords, where it grew from the body of the sacrificed god of maize, who was defeated by the lords of the Underworld in an earlier era.

In this Article

MYTH: Cacao and maize (corn) in Popol Vuh

The Popul Vuh manuscript is the Sacred Book of the Quiché/K’iche Maya. The document – along with Quiché/K’iche oral traditions – was discovered and summarized in Latin during the 16th century by Father Francisco Ximénez, a Dominican priest, who served in the Guatemala highlands at Santo Tomas Chichicastenango. The document reflects the cosmology, religious practices, and history of the Maya.

In the Popol Vuh, the Maya creation story, cacao is named as one of many food items, including maize, which emerge from the “Mountain of Sustenance” prior to the creation of humankind.

Cross culturally, trees supply a rich collection of metaphorical meanings appropriate to generational descent, and in Maya ideology they evidently constitute a bridge between death and rebirth. It is the Maize God’s manifestation as a fruit tree that allows him to pass on his procreative seed and to eventually triumph through the heroic deeds of his offspring.

The deities of importance to this story include the maize God Nal, Chaak or K’awil, and various Underworld lords, including the paramount death god and a deity known by the designation God L. God L played various roles in Maya mythology, representing a merchant deity, an Underworld lord, and a Venus god.

The two varieties of cacao mentioned in the Popol Vuh include both cacao and pek, or pataxte, Theobroma bicolor, a species related to Theobroma cacao, but of inferior quality and taste.

Iconographic images from Classic period ceramics and stoneware reveal a significant and continuing connection between cacao and maize. Karl Taube has proposed that the Maize God is equivalent to Hun Hunahpu in the Popol Vuh, whose death and rebirth represent the agrarian cycle of planting and harvesting maize.

The Popol Vuh and Hun Hunahpu

While there is no overt reference to Hun Hunahpu as either a deity of maize or cacao in the Popol Vuh, a closer examination of symbolic and linguistic elements in the text reveals several possible references to cacao that relate directly to the Hero Twins, the children of Hun Hunahpu, and their own journey of death and resurrection.

The self-sacrifice and rebirth of the Hero Twins as fish-men appears to serve as both a metaphor for the multiple stages of cacao processing, and is associating fish and cacao both through the spoken word kakaw, and the written form of this word that uses a fish glyph.

PAXIL – The Sustenance Mountain

According to Mayan religious beliefs, cacao had a divine origin. In the creation story recorded in the Popol Vuh, cacao is one of the precious substances that is released from “Sustenance Mountain” (called Paxil, meaning ‘broken, split, cleft’), along with maize, from which humans are made, at the time just prior to the fourth or present creation of the world.

These are the names of the animals which brought the food:

Yac [the mountain cat], utiú [the coyote], quel [a small parrot], and hoh [the crow]. These four animals gave tidings of the yellow ears of corn and the white ears of corn, they told them that they should go to Paxil and they showed them the road to Paxil.

And thus they found the food, and this was what went into the flesh of created man, the made man; this was his blood; of this the blood of man was made. So the corn entered [into the formation of man] by the work of the Forefathers.

And in this way they were filled with joy, because they had found a beautiful land, full of pleasures, abundant in ears of yellow corn and ears of white corn, and abundant also in pataxte [Theobroma bicolor] and cacao [Theobroma cacao], and in innumerable zapotes sapote fruit) , anonas (pineapple), jocotes (Spondias purpurea fruit), nantzes (nance fruit), matasanos (Casimiroa sapota o Casimiroa edulis fruit), and honey.

There was an abundance of delicious food in those villages called Paxil and Cayalá. There were foods of every kind, small and large foods, small plants and large plants.

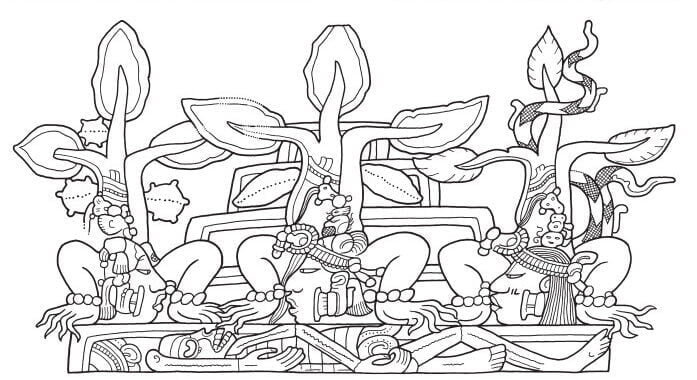

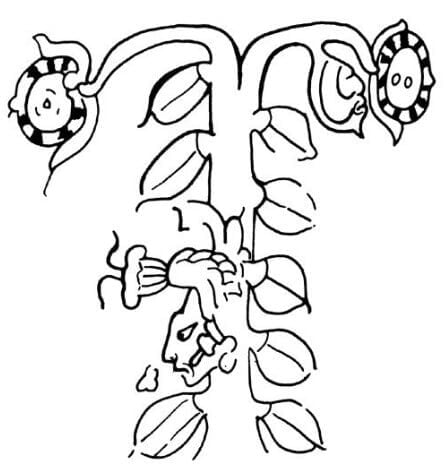

The body, now reduced to a skeleton, buried beneath a stepped pyramid. The surrounding stony volutes and their animated covering of life (omitted in the illustration for the sake of clarity) emphasize that we are still within Sustenance Mountain, the conceptual prototype for funerary pyramids.

Three anthropomorphic trees surmount the cadaver. Fertilized by, or erupting directly from it, their bodies are inverted, with fingers spreading to form sinuous roots, their torsos and legs transformed into trunks and leafy branches. The model for this posture is clear, the sky-supporting “World Trees”.

Of the three tree figures, the central one sprouts cacao pods, the one on the left bears a spiked fruit that may be guanabana (Annona muricata L.), and the one on the right has a snake-like design that may represent a vine or creeper, explains Simon Martin.

The themes of decomposition and transformation on both the Berlin vase and Palenque sarcophagus resonate strongly with the mythology of Central Mexico and a description in the sixteenth-century Histoyre du Mechique. Here the Maize God Centeotl buries himself in the floor of a cavern and from his body grows corn, as well as the fruits and seeds of other useful plants:

[Centeotl] put himself under the ground, and from his hair emerged cotton, and

from an eye a very good seed which they eat gladly, called cacatzli. . .

From the nose, another seed called chia. . .

From the fingers came a fruit called camotli. . .

From the fingernails another kind of broad maize, which is the kind they eat today.

And from the rest of the body emerged many other fruits, which the men gather and sow.

Jonghe. 1905.

Cacao, the most coveted product of the mortal orchard, was emblematic of all prized and sustaining the growth of vegetables – with the exception of maize – and the myth served to explain how foods came into being.

The Cacao tree and the Maize deity

Mary Miller and Simon Martin have subsequently suggested that the intimate iconographic relationship between cacao and maize (corn) reflects their importance within Maya cultures, and that cacao may be associated with the transformation and rebirth of the Maize God.

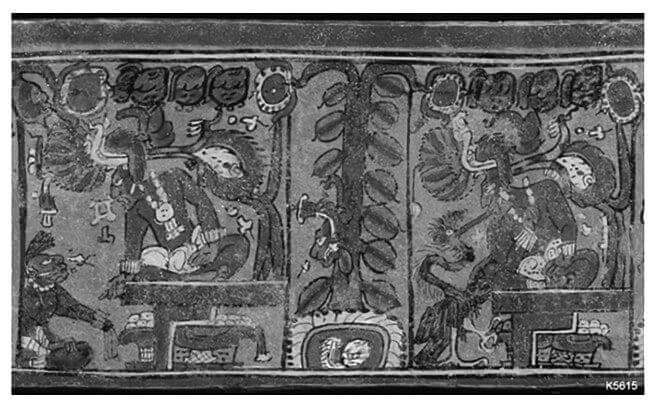

References to cacao have been found within ancestral versions of the Maya creation story. First noticed by Taube, K5615 1, a Classic period Maya vase from Nebaj, appears to depict an image related to an important passage of the Popol Vuh.

Here, Allen Christenson translates the tree as a possible cacao tree, with fruit emerging directly from the trunk.

In this highly stylized tree hangs the tonsured head of the Maize God, the equivalent of the father of the Hero Twins, Hun Hunahpu, who had been decapitated by the Lords of Death in the Underworld of Xibalbá after he and his brother were defeated there.

There are two nearly identical cacao trees on vase K5615, each with a human head on the trunk, though a fruit hanging in the upper branch of the tree on the left appears with a human face.

This may be a representation of the transformation of the head of the Maize God into a cacao pod.

The Maize God may also be a deity of cacao

Among fruit, cacao appears to have a particular relationship with maize. As Miller and Martin have noted, the seeds inside a cacao pod are arranged much like the kernels of an ear of maize in both form and color, though they are somewhat larger.

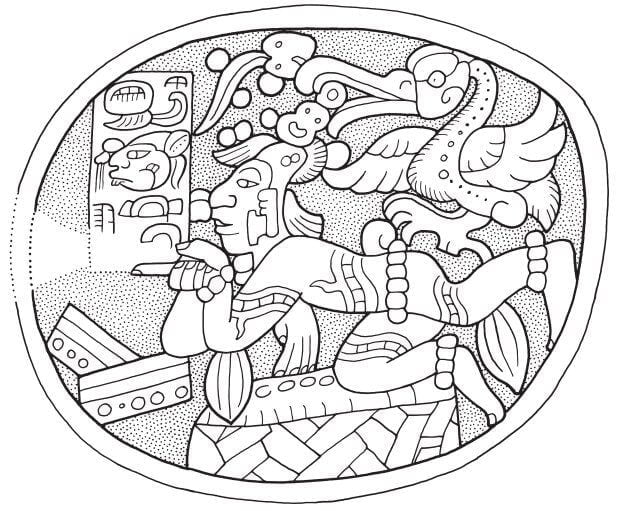

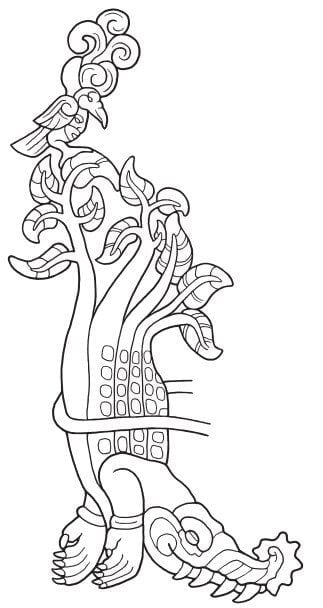

Miller and Martin have proposed that the Maize God may also be a deity of cacao, as is evident in an image from a carved, gourd shaped stone vessel (K4331) that depicts the Maize God as an anthropomorphic tree covered in cacao pods.

This vessel appears to name the figure depicted as iximte’ ‘maize tree’. Martin additionally proposes that the arboreal Maize God as the iximte’ is related to the inverted caiman imix yaxche ceiba world tree, with which the Maize God is often conflated and named. Furthermore, inverted human or caiman forms are similarly depicted with vegetation and fruit emerging from their bodies, including cacao fruit.

man protagonist as a “Maize Tree” (F2). Unprovenienced stone bowl. (K4331). Early Classic period. The Dumbarton Oaks collection, Washington, D.C. Drawings by Simon Martin after a painting by Felipe Dávalos in Coe 1975 and a photograph by Justin Kerr.

The inverted Caiman Imix Yaxche Ceiba World Tree

The ceiba has ovoid seedpods that closely resemble the cacao fruit, and the Maya compare the shape of cacao pods with human breasts on several ceramic vessels found in the Popol Vuh museum in Guatemala City.

Today, young girls in the Yucatec village of Chan Kom are told that playing with the fruits of the ceiba will make their breasts grow too large.

With green bark and spines reminiscent of a crocodile, the ceiba (Ceiba pentandra) is likened to an inverted caiman throughout Mesoamerica, while the caiman itself is a common symbol for the fertile, mountainous surface of the earth floating upon the ocean. Therefore, it would follow that the iximte’ as the caiman tree emerges as the offspring of the caiman-like earth.

Martin suggests that the head of the arboreal Maize God may symbolically represent all fruit from the iximte’ world tree.

The Cacao Tree and the Calabash

As Taube notes, the apparent cacao tree depicted in K5615 is a likely parallel of the tree of Puk’b’al cha’j of Popol Vuh, in which Hunahpu’s head is placed.

However, in the Popol Vuh, this tree is said to be a calabash, or gourd tree (Crescentia cujete), and the skull of Hun Hunahpu, a calabash gourd. Both calabash and cacao trees share the quality of producing large fruit from flowers directly on the trunk, a characteristic known as cauliflory.

Such fruits can be seen to resemble heads hung in a tree, but the fruits of the cacao and the calabash share additional, unique similarities.

The calabash itself is associated with the traditional K’iche’ and pan-Mesoamerican practice of drinking chocolate, and the thin-walled, hard shelled and watertight calabash gourd is still used for the chocolate drink.

These gourd-cups are referred to in the Popol Vuh as the skull of Hun Hunahpu.

Furthermore, the calabash gourds used for the celebratory chocolate drink resemble some forms of ceramic vessels depicting Classic period Popol Vuh imagery. The glyphs, Primary Standard Sequence (PSS), on the rims of many of these vessels identify them as containers for various cacao drinks. Their thin walls imitate the thin shell of the calabash gourd-skull, and some glyphic texts refer to this quality: hay y-uch’ab

‘thin-walled drinking vessel’ and u-tsimal hay, ‘his thin gourd’.

At the beginning of Part Three of the Popol Vuh, the authors introduce Hun Hunahpu, and his brother Vucub Hunahpu, asking us to drink to the Father of the Hero Twins.

Tedlock interprets this as raising a calabash gourd of chocolate, the traditional drink of K’iche’ “Masters of Ceremony” nim chokoj (possibly from K’iche’ chokola’j, connoting the gathering of food and drink, specifically cacao, for a banquet). This symbolic drinking from the skull of Hun Hunahpu precedes the story of the origin of the calabash, and the story of Hun Hunahpu, which then unfolds.

While the calabash and the cacao tree may be regional or temporal variations in the creation story, the two may have been simultaneously used and not mutually exclusive, as is often the case with richly metaphorical and overlapping Maya imagery.

In the Popol Vuh, the tree of Puk’b’al cha’j in which Hun Hunahpu’s head is placed was previously barren. When his head is put in the fork of the branches, many fruit begin to appear, indistinguishable from his head. This unusual tree is then marked as forbidden by the Lords of Death, though rumors spread in Xibalbá of the sweetness of its fruit.

As Tedlock notes in, Popol Vuh. The Definitive Edition of the Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life and the Glories of Gods and Kings, the calabash fruit itself is relatively inedible, let alone sweet.

However, the fruit pulp of the cacao tree is very sweet, and the flesh surrounding the raw beans is highly sought after, consumed fresh as fruit, as juice or fermented as a wine. If the fruit in question is cacao, it would explain the rumors circulating in Xibalbá; however, if it is a calabash gourd, perhaps the sweetness refers to the cacao beverage contained within it.

The impregnation of Xkik’ or Lady Blood by the gourd skull

In the myth, the citizens of Xibalbá are forbidden to go near the tree, but the maiden Xkik’, or Lady Blood, approaches the tree in secret.

The maiden Xkik’ encounters the skull in the tree:

“What’s the fruit of this tree? Shouldn’t this tree bear something sweet?

They shouldn’t die, they shouldn’t be wasted. Should I pick one?” said the maiden.

And then the bone spoke; it was here in the fork of the tree:

“Why do you want a mere bone, a round thing in the branches of the tree?” said the head of One Hunahpu when it spoke to the Maiden.

“You don’t want it,” she was told.

“I do want it,” said the maiden…

Xkik’ reaches up to touch the fruit, the skull of Hun Hunahpu, and he spits into her hand.

He tells her that she would then become the mother of his twins, and that she must leave the underworld. With the help of owl messengers, Xkik’ escapes her impending sacrifice after her father and the Lords of Death discover her pregnancy. The owls return her safely to the surface of the earth, where her children, the Hero Twins, Hunahpu and Xbalanque, are born.

God L

Xkik’ is the daughter of Kuchuma kik’, an underworld lord who has been associated with God L of the Classic period, the patron of merchants and cacao. God L is related with cacao wealth as well as having ties to commerce and long-distance trade (depicted in murals at Cacaxtla, Mexico and narrative in the Popol Vuh).

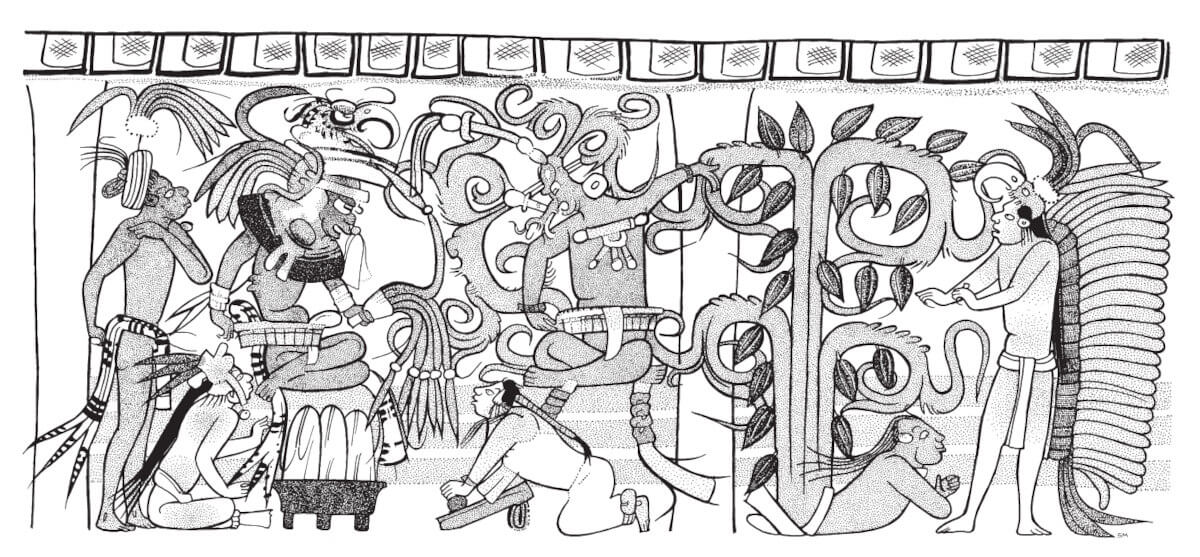

In the murals of Cacaxtla, Mexico, we see him as a trader, his hat resting atop a large merchant’s pack. Interestingly, this scene seems to be another version of the transformation story.

Set in a symbolic netherworld at the foot of a stairway (omitted from the drawing), God L faces a cacao tree. But the scene continues up the steps, toward the earth’s surface, where the tree is replaced by a series of cornstalks on which each cob is the head of the reborn Maize God.

Martin discusses the role of God L as the principal foe of the Maize God, and the Classic period parallel of one of the Lords of Death. The merchant God L thus becomes the wealthy owner of the underworld cacao tree into which the Maize God initially transforms.

A relatively rare appearance of cacao pods in a painted ceramic scene, on a vessel known as K631, provides important information. Seated in a throne room is God L—identified by the owl avatar, or familiar, in his broad hat—the most senior and powerful lord of the Maya Underworld.

As an aged figure with jaguar characteristics, he is often shown with a decorated cape, a staff, and a cigar. On K631 he converses with the fiery, torch-headed K’awiil, who gestures toward an anthropomorphic tree weighted with cacao pods. Essentially the same inverted figure depicted on the Berlin vase (K6547). A woman is grinding cacao on the metate (stone grinder).

This tree man, in turn, interacts with a standing companion dressed in a scarlet macaw headdress and feathered “back-rack.” Like the corresponding gods in the Popol Vuh, One Death and Seven Death, God L would have presided over the demise of the Maize God and possessed the resulting Maize Tree. This would explain why he is associated with the wealth of cacao.

The use of cacao as monetary exchange would similarly explain God L’s ties to commerce and long-distance transport.

K’awiil

There is also a link between lightning K’awiil and human sustenance (Maize God) in central Mexican mythology (Codex Chimalpopoca) as well as Quiché/K’iche Maya accounts which are portrayed in vessel K631 where K’awiil carries a cacao sack with “kakaw” glyphs (a).

The text on a second capstone (b), this one from the site of Dzibilnocac, Mexico, mentions an ox wi’il ‘abundance of food’ and lists bread, water, and cacao (here rendered as ka-wa), which are shown stacked in plates, sacks, and baskets. Possibly this is also a link to commerce, cacao – money or offering.

Kawiil’s cacao offering

A painted capstone from the Temple of the Owls in Chichén Itzá, depicts the spiritual significance of cacao and the cenote. The cacao tree was grown in humid, soil-filled sinkholes, known locally as cenotes (corrupted from the Mayan dzonot).

They seem to have been the private property of wealthy lineages, but they could never have produced very much cacao.

Martin states, the association here is in placing the origin of cacao in the Underworld.

Fertility ritual and sustenance: Cacao chilate

Throughout Mesoamerica, cacao is used to symbolize fertility in marriage ceremonies.

Among the Ch’orti’, Girard describes how the ritual beverage of chilate is used in an important agricultural ritual to fertilize the earth. Representing the dual aspects of the cosmos, a dark cacao chilate, and a white maize chilate are used.

The cacao chilate is offered to the deities and consumed in gourd cups, while the white chilate is poured along the vertical axis of a foliated cross and into the earth from a calabash gourd. This parallels the above passage of the Popol Vuh, and the impregnation of Xkik’ by the gourd skull.

How humans came to be: Xmucane

As the children of Hun Hunahpu and Xkik’, the Hero Twins themselves are later represented by maize plants that are planted in the center of the house of their grandmother, Xmucane. As the story goes, these twins again travel to the underworld to face their own death and resurrection.

When these twins die, their maize plants likewise wither and die on the surface of the earth. But with their resurrection, the maize plants once again grow green.

Xmucane then grinds white and yellow maize from the Mountain of Sustenance to form the bodies of the first human beings at the beginning of the current creation.

Girard describes the Ch’orti’ preparation of boronté (nine-drink) during a ceremonial banquet. This chilate is composed of maize, cacao and pure water from a sacred spring.

He sees this as a direct parallel with the Popol Vuh story of Xmucane who makes “nine drinks” from the foods found in the Mountain of Sustenance, here represented by maize and cacao. These drinks are seen to be the source of “life, strength, and vigor” for the newly created humanity.

Alan Christenson alternately translates this passage as describing maize that is ground fine “with nine grindings by Xmucane,” nonetheless noting the unique creative power of Xmucane as the elder female who acts alone to create human flesh, with nine being the number of months of human gestation.

The mythical and symbolic association of cacao with maize is clear. As Mary Miller and Simon Martin note, they are the two most important crops in the Quiché/K’iche Maya economy.

It is not surprising to see this important relationship reflected in mythology. While the Popol Vuh describes maize itself as the symbolic and literal raw material out of which the original people are made, cacao may have been another key ingredient which brings humanity to life.

Cacao and the Hero Twins

While the Hero Twins are compared with terrestrial maize in the Popol Vuh, their simultaneous death and rebirth in the underworld strongly suggests an association with cacao.

The rebirth of the Maize God and the corn cycle

Although several episodes in the Maize God’s complex journey remain to be explained, scholars can say with confidence that the corn cycle was the central metaphor of life and death for the Maya and the nucleus around which much of their religiosity was formed.

This parallels the rebirth of the Maize God emerging from the crack in the back of the Earth turtle, as seen in several images from Classic period ceramics.

In this scene from the Resurrection Plate (K1892), the Hero Twins preside over the rebirth of their father, with their names appearing above their heads as Hun Ajaw and Yax Bahläm. The Maize God is here named as the caiman maize tree, apparently reading ‘One Maize Caiman’ as Hun Ixim Ahin.

This pattern follows Martin’s observation that cacao is associated with the underworld, while maize appears as its analogue on the surface of the earth. With their father likened to a cacao tree, the Hero Twins may metaphorically represent cacao seeds, and their fate in the underworld implicitly illustrates this comparison.

When the Hero Twins come of age, they discover the ball game equipment of their father and uncle. Like their father and uncle before them, the twins soon anger the Lords of Death by playing loudly, and they are then invited to play another deadly game of ball in Xibalbá, but this time something is different. These twins are smarter and more fearless, as they are endowed with magical powers.

The twins endure many tests, including the ball game, but they are not defeated. They pass through the houses of cold, knives, fire, jaguars, and bats, and persist, despite even the decapitation of Hunahpu.

Eventually, after a final ball game, the Lords of Death tire of their adversaries’ ability to outsmart them, and they plot to kill the twins by inviting them to a drinking celebration. Here, the Lords of Death plan to burn the twins in a pit oven disguised as a vat used to prepare an intoxicating sweet drink.

ki’: fermented cacao wine

The precise word for the drink in the Popol Vuh is ki’, or ‘sweet drink’– commonly known as a boiled, fermented, maguey and honey mixture. The term ki’ confers the meaning of sweet, delicious, and rich throughout the Quiché/K’iche Maya area, within both K’iche and Yucatec. Though often associated with maguey, ki’ also refers to chicha, a fermented drink made from a variety of fruits, berries or maize.

The drink mentioned in the Popol Vuh may well have been fermented cacao wine made from the boiled pulp of the fresh cacao pod, known to have been made by the Quiché/K’iche Maya and elsewhere in Mesoamerica. Considering the following passage, this remains a strong possibility.

The multi-stage process of refining corn and/or cacao

The Lords of Death invite the twins to jump over the drink, with the intention of pushing them into the fire. Instead, the twins decide to willingly jump directly into the flames. Here, like cacao bean children of their cacao pod father, the twins are burned and their bones are ground into powder on a metate, “just like hard corn is refined into flour”.

This reference to corn would at first seem to suggest that the twins represent the preparation of maize. However, a closer analysis of this passage reveals that it parallels the complex, multi-stage process of refining cacao as described in Young:

- the burial of the seeds and pulp (entering the underworld)

- fermentation (fermented sweet drink)

- roasting (jumping into the fire)

- grinding (bones ground on metate)

- mixing with water (poured into a river)

This passage may metaphorically describe the origin of cacao use and the processing of the ritual drink.

However the complex technology of cacao processing was discovered, the mythical retelling of this process in the K’iche’ narrative of the Hero Twins may reveal underlying spiritual and symbolic meanings associated with cacao.

This metaphor of cacao processing in the Popol Vuh continues as the powdered bones of the twins are spilled into a river. When mixed with the water of the river, much like the last stage of making the cacao drink, the twins are soon resurrected as two fish-men, which then transform back into masked human forms of Hunahpu and Xbalanque:

They were seen in the water by the people. The two of them looked like catfish [winaq kar, literally ‘person fish’] when their faces were seen by Xibalba.

And having germinated in the waters, they appeared the day after that as two vagabonds…

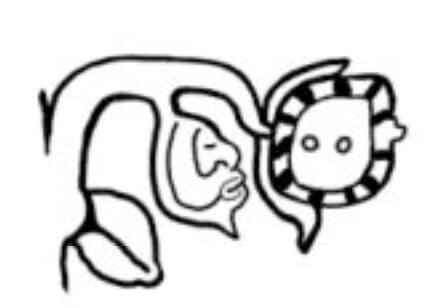

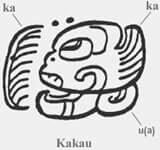

The cacao – fish glyph

The written form of kakaw visually suggests a fish.

A typical Late Classic period cacao glyph with the fish ka sign before wa. The two small dots in front of the fish’s mouth serve as a “doubler” for the ka.

Morphologically, the word kakaw does not appear to be of Mayan origin, and the pan- Mesoamerican and pan-Mayan presence of this word suggests an ancient origin and distribution. Several authors have proposed that related terms for kakaw originated in either Mixe-Zoquean or Uto-Aztecan language families.

There is a potential association between words for ‘fish’, ‘two’, and ‘cacao’ within most Mayan languages. The similarity of kakaw and such forms as ka’ kar, ‘two fish’, could have been a verbal source of the fish transformation episode in the Popol Vuh. However, several questions remain.

If we accept that the K’iche’ authors recognized the transformation of the Hero Twins as a metaphor for processing cacao, are the visual and verbal puns on kakaw and fish a mere coincidence?

If one or both of these puns were recognized by the K’iche’, were they also recognized by Lowland Maya cultures in the Classic period? Was there a similar story of fish transformation in the Classic period? If so, did this have anything to do with cacao?

The ambiguity about the role of cacao in the Popol Vuh is heightened when we read in one post-Conquest source that Hunahpu (one of the Hero Twins) invented the processing of cacao. While this claim is mentioned in other sources, it appears nowhere in the Popol Vuh, but then we know that we do not have the complete version of the epic, at least as it was known to the Classic Maya.

Just to confuse things, it seems that the Hero Twins’ names were later adopted as personal names by some native political leaders, just as “Hercules” or “Zeus” appear in Renaissance and modern Europe or “Raja” in India.

The Quiché manuscript of Francisco Garcia Calel Tzunpán, mentions that a king, Hunahpú, was the discoverer of cacao and of cotton. This “Hunahpú” mentioned was supposedly an early Quiché Maya lord in the Guatemalan highlands …

~ ○ ~

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- A concise history of chocolate. https://www.c-spot.com/atlas/historical-timeline/

- Anonymous, The Vertues of Chocolate East-India Drink, one page. This apparently was taken out of Antonio Colmenero, Chocolate: Or, An Indian Drink, translated into English by James Wadsworth.

- Christenson, Alan. Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Maya. 2003.

- Clarence-Smith William Gervase. Cocoa and Chocolate. 1765–1914. 2000.

- Coe, Sophie D., Michael D. Coe, and Ryan J. Huxtable. The true history of chocolate.1996. Thank you.

- Colmenero de Ledesma, A Curious tretise on the nature and quality of chocolate. Trans. Don Diego Vades-forte [James Wadsworth].1640.

- Colmenero de Ledesma. Curioso Tratado de la naturaleza y calidad del chocolate. Madrid, 1631. (Latin 1644)

- Fao infographik http://www.fao.org/resources/infographics/infographics-details/en/c/277756/

- Girard, Rafael.Esotericism of the Popol Vuh: The Sacred History of the Quiché Maya. Theosophical UniversityPress, Pasadena. 1979.

- Grivetti Louis E., Shapiro Howard-Yana. Chocolate – History, Culture, Heritage.

- Grivetti Louis Evan & Shapiro Howard-Yana. Chocolate: History, Culture and Heritage. 2009. [NOTE: this book offers extensive descriptions and translated excerpts from primary documents describing Early New Spain chocolate recipes.]

- Grofe Michael J. The Recipe for Rebirth: Cacao as Fish in the Mythology and Symbolism of the Ancient Maya.

- Grofe Michael J. The Recipe for Rebirth: Cacao as Fish in the Mythology and Symbolism of the Ancient Maya. 2007. Thank you.

- https://foodtimeline.org/foodmaya.html#hotchocolate

- https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/maya/chocolate/history-and-uses-of-cacao.

- Kaufman Terrence. Justeson John. The History of the word for cacao in ancient Mesoamerica. 2008. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/ancient-mesoamerica/article/history-of-the-word-for-cacao-in-ancient-mesoamerica/FE4A2AE4F9D0C1EDCFB583DB315907E4

- Levin Carole. How Sweet It Is: From the Mountains of Mexico to the Streets of York. Torch Magazine. 2018. http://www.ncsociology.org/torchmagazine/v913/Levin.pdf

- Martin Simon. “Cacao in Ancient Maya Religion: First Fruit from the Maize Tree and Other Tales from the Underworld,” in Chocolate in Mesoamerica: a Cultural History of Cacao, ed. Cameron L. McNeil (University Press of Florida, 2006), 179.

- Martin, Simon. “Cacao in ancient Maya religion: first fruit from the maize tree and other tales from the underworld.” Chocolate in Mesoamerica: a cultural history of cacao. 2006. Thank you.

- Maxwell Kenneth A Sexual Odyssey: From Forbidden Fruit to Cybersex. New York: Plenum.1996.

- McNeil Cameron L. Chocolate in Mesoamerica A Cultural History of Cacao. 2006.

- Moreiras, Diana K. Thinking and Drinking Chocolate: The Origins, Distribution, and Significance of Cacao in Mesoamerica. 2010.

- Pre-Hispanic City of Chichen-Itza. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/483

- Sahagún, Bernardino de. La historia general de las cosas de Nueva España. 1552. [Nahuatl/Spanish]. Known as the Florentine Codex. The Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain. Trans. Arthur J.O. Anderson and Charles Dibble, 12 books in 13 volumes. Santa Fe: School of American Research, U of New Mexico P, and U of Utah P, 1950.

- Taube, Karl A. “The Classic Maya Maize God: A Reappraisal,” Fifth Palenque Round Table. 1983.

- Taube, Karl A. Aztec and Maya Myths: The Legendary Past. University of Texas Press. 1993.

- Tedlock, Dennis. Popol Vuh. The Definitive Edition of the Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life and the Glories of Gods and Kings. 1996 .

- The Vertues of Chocolate East-India Drink. Oxford: Henry Hall. 1660.

- Turices, Santiago Valverde. Un Discurso del chocolate. Seville, 1624.

- Young, Allen M.The Chocolate Tree: A Natural History of Cacao. Smithsonian Institution Press. 1994.

Keep exploring: