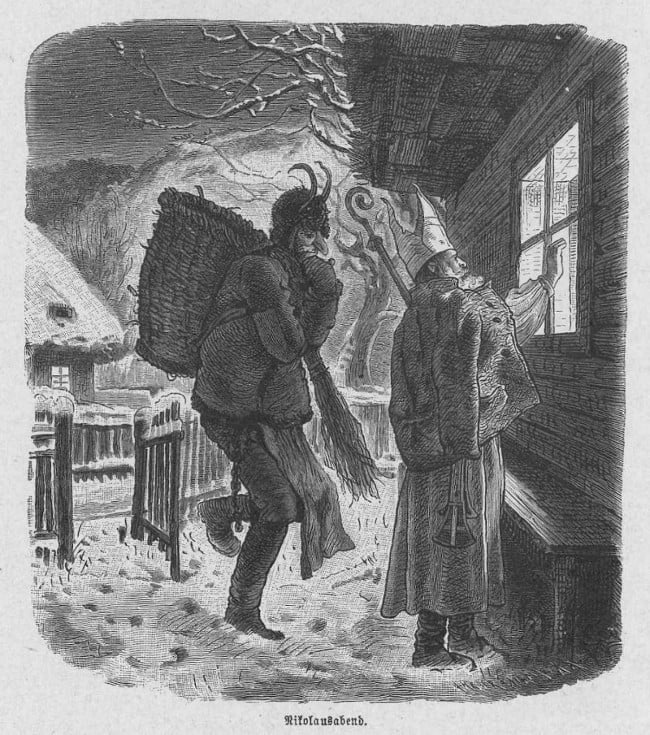

Saint Nicholas with his long white beard, bishop’s miter and crosier rewards the well-behaved with gifts each year on 6th December. His scary counterpart Krampus wears fur, horns and a hand-carved mask with a lolling tongue, he comes to warn and punish naughty children (and adults). Discover Saint Nicholas and the Krampus in Tyrol.

In this Article

It’s the snow-swept Alps the Krampus himself arose. The arrival of the Perchten (Krampus) traditionally marks the start of winter in Tyrol. In Central and Eastern Alpine folklore, Saint Nicholas and Krampus, bring presents to children who have been good throughout the year.

Everyone knows:

| Fuer’s Schlimme gibt’s vom Krampus Strafe, St Nikolaus belohnt das Brave. | Krampus punishes the wicked, St Nicholas rewards the good. |

Every evening of December I would get a golden cross painted into a book, that only St. Nicholas (the saint of the children) would see. Grandma would ask me every evening:

“Have you been a good child?”

My Omi (granny) kept this ritual going as long as I would believe that Saint Nicholas would be a magical saint coming to visit us and bringing gifts. Krampus would come to our house on December fifth. Saint Nicholas was with him to give me candies, oranges, nuts and figs after looking for golden crosses in his book.

Krampus would stand in the background, looking menacing and terrifying. He was there to warn me to stay on good behavior the rest of the year.

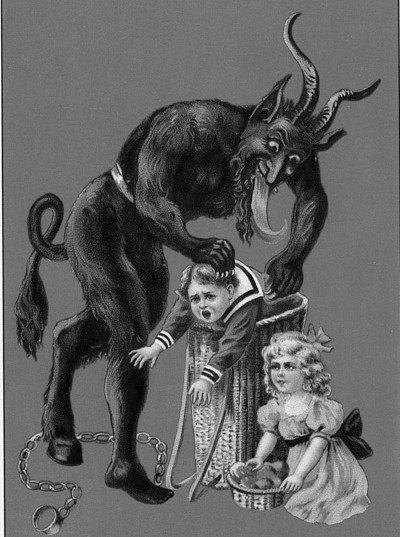

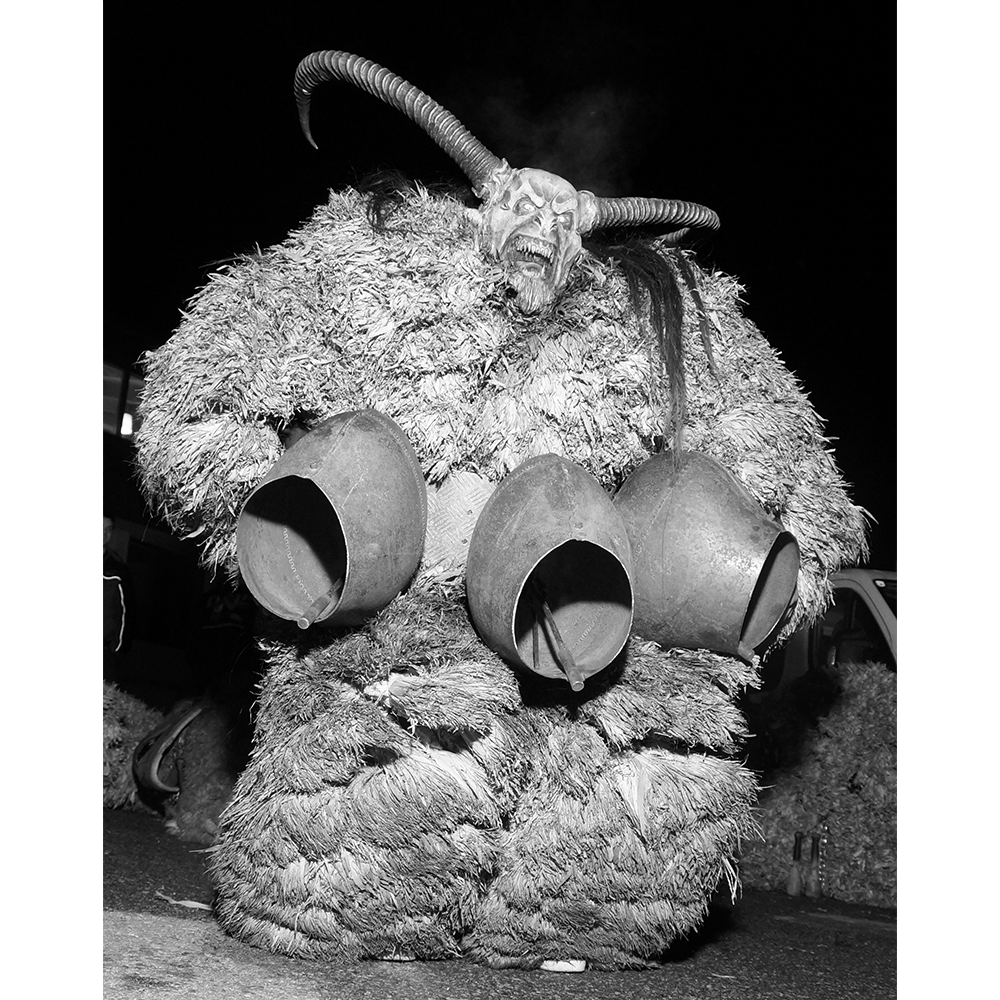

The Tuifel, how it was also called in my home, was looking atrocious, covered in fur, with his wooden carved mask, long Horns, bells and chains. On his back, he would carry an empty bag or basket, to stuff naughty children in, and take them away.

Tyrol is where the Krampus dwells

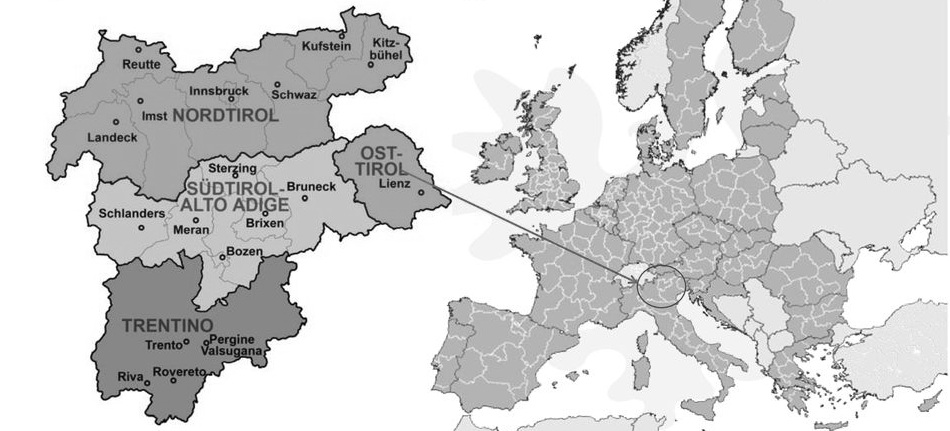

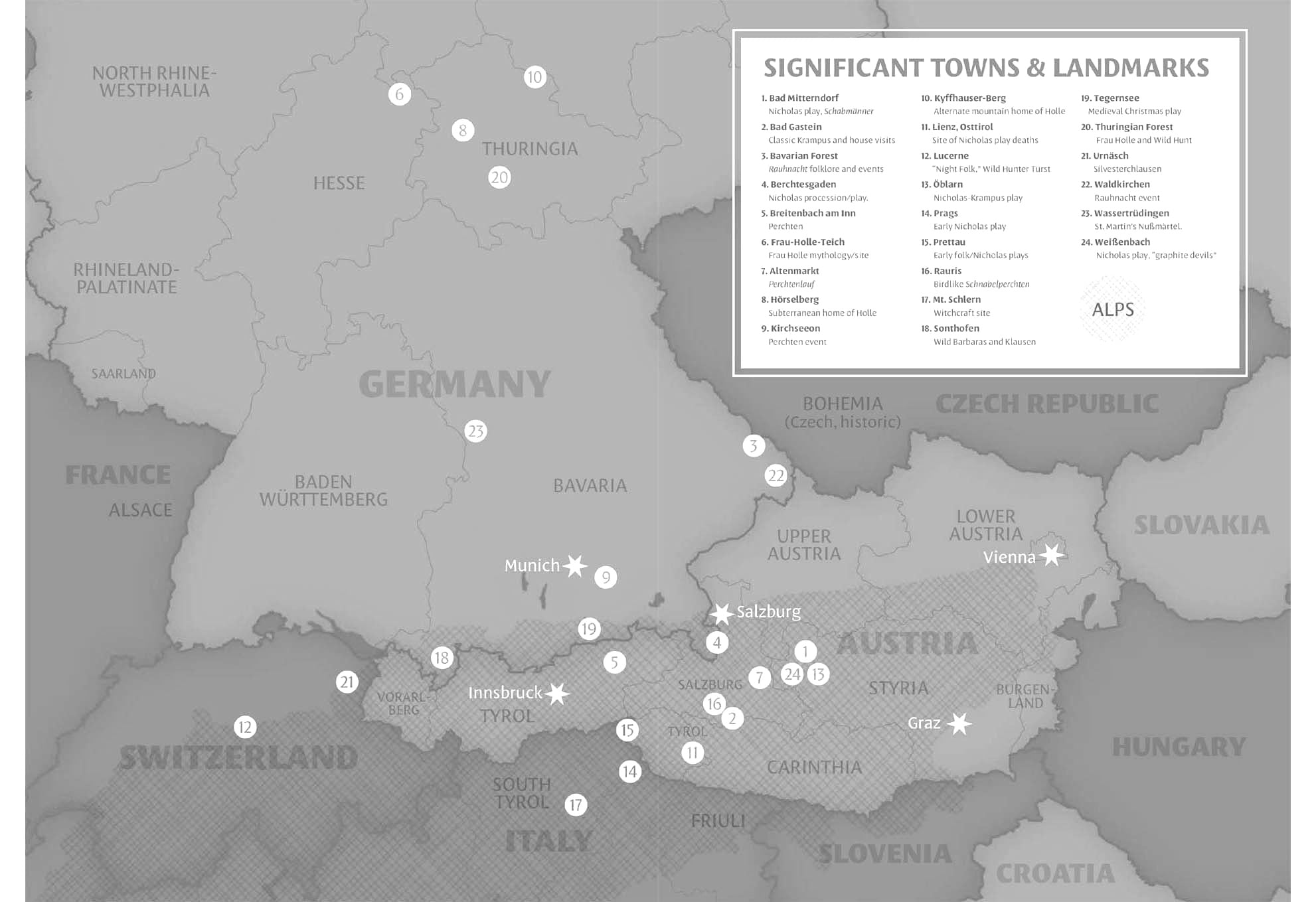

Traditionally young men dress up as the Krampus in Tyrol, North- and Easttirol being part of Austria and the Tirolean (a Austrian dialect) – speaking area of Italy, Trentino – Alto Adige or South Tyrol.

Alpine regions of Austria, southern Bavaria (Germany), Switzerland and Slovenia also know the Krampus. In Italy also Val Canale in Tarvisio, Ugovizza and Malborghetto in Friuli-Venezia Giulia, and some areas of Belluno in Veneto, reflect Alpine influence with Krampus traditions. Krampus is also found in parts of the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania and Croatia.

During the first week of December, particularly on the evening of 5th December, the eve of Saint Nicholas Day, Krampus troupes roam the streets frightening with rusty chains and bells or visit houses and inns with St. Nicholas.

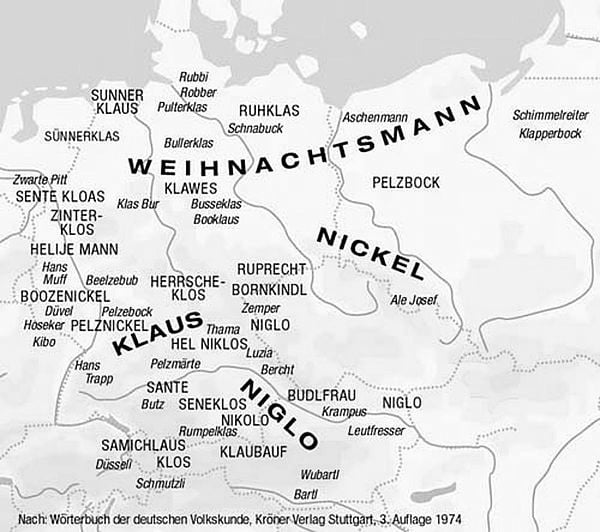

There are many names for Krampus, as well as different regional variations in portrayal and celebration. As with the distinct dialects and traditional costumes that characterize nearby valley communities, the historic obstacles involved in traversing the Alps focused and preserved Krampus customs in their highly localized form. This regionalism, affects every aspect of alpine folklore of the Krampus and saint Nicholas.

Hand-carved, wooden masks, heavy and elaborate dresses made of lamb- and goat skin or fur and traditional willow or birch branches brandished as weapons are common futures. Although he is “officially” the servant of Nikolaus, during the Krampuslauf – Krampusnight, often the wild hunt can parade trough villages and towns, without the saint, to dictate them.

ETYMOLOGY: Krampus

Krampus is not really an individual’s name but a class of “devil”. Pronunciation is: kram‧pus. For the curious—since it’s often asked—the correct plural for Krampus in German would not be the faux-Latinate “Krampi” but Krampusse.

Krampus is understood to derive from the Middle German “Kralle”, “claw” or from the Bavarian “Krampn” referring to something lifeless, dried out, or shriveled, the latter pointing to a connection between the Krampus and the spirits of dead.

There are many names for Krampus. In East Tyrol, and in older manuscripts, Klaubauf is the preferred term. Also Bartl or Bartel, Niglobartl, and Wubartl are used. Tyroleans may simply refer to him as the Tuifl (dialect for “devil”), and similarly Toifl.

Sometimes, believing that the devil’s name is unlucky to speak aloud, a circumlocution describing, rather than naming might be used, like Ganggerl or Gankerl (probably from “Gang” or “gait”), a name which may also derive from the distinctive lope or hopping gait performers adopt.

In the Bavarian foothills and the area around Salzburg (Austria), the preferred term is actually Kramperl. Pelzebock or Pelznickel is used in southern Germany, and Gumphinckel in Silesia. Hungary, he is Krampusz and in Switzerland, Schmutzli.

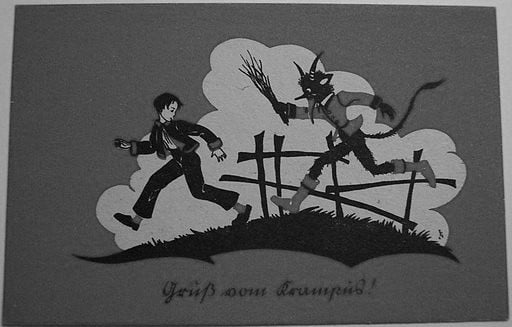

Krampus postcards

The word Krampus, gained wide usage in the late 19th and 20th century with the circulation of Krampus cards, and has only recently returned thanks to reprint and online use.

The use of Krampus postcards, emerged in Vienna, and soon spread to other German-speaking cities through the introduction of the postal card in Austria-Hungary in 1897. People began to send each other red postcards in the weeks leading up to Christmas that depicted the Krampus, often with a short poem, humorous phrases, and the tagline “Gruß vom Krampus — Greetings from Krampus”.

ETYMOLOGY: St. Nikolaus or Nicholas

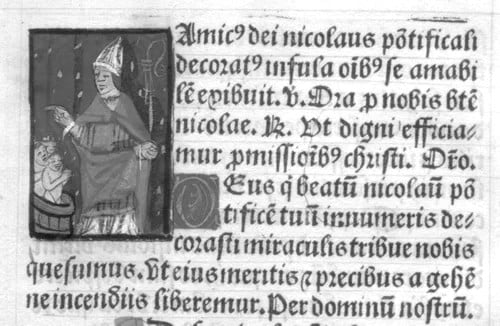

St. Nicholas, also called Nicholas of Bari or Nicholas of Myra, is one of the most popular saints commemorated in the Eastern and Western churches.

The name derives from Syrian, Soche, Zakka, Zeka, “victory”; from Greek Nikholaos, literally “victory-people,” from nikē “victory” and laos “people”. Latin Nicholaus; from French Nicolas, Nicolaus,

Saint Nicholas, or “the Holy Nicholas” as it’s rendered in German, goes by a variety of appellations. Sometimes he’s simply “the Holy Man,” “the Good Man” or “the Friend of Children”. He may also just go by “Nikolo,” an Austrian dialect rendering of “Nicholas.”

Colloquial Old Nick “the devil” is attested from 1640s, evidently from the proper name, but for no certain reason.

Nicholas’s existence is not attested by any historical document, so nothing certain is known of his life except that he was probably bishop of Myra in the 4th century. Myra is in Anatolia, modern Demre, Turkey.

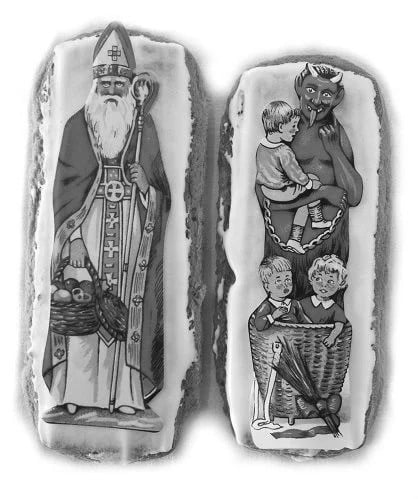

The white-bearded Saint Nikolaus, dressed in splendid robes and complete with miter and crosier, enters each house in order to fill the children’s shoes with small gifts or bring presents in red sacks or plates of cookies, candies, nuts, apples, and oranges.

St. Nicholas formed the basis for the figure known as Santa Claus (created in the 19th century from Dutch Sinterklaas), the bringer of gifts.

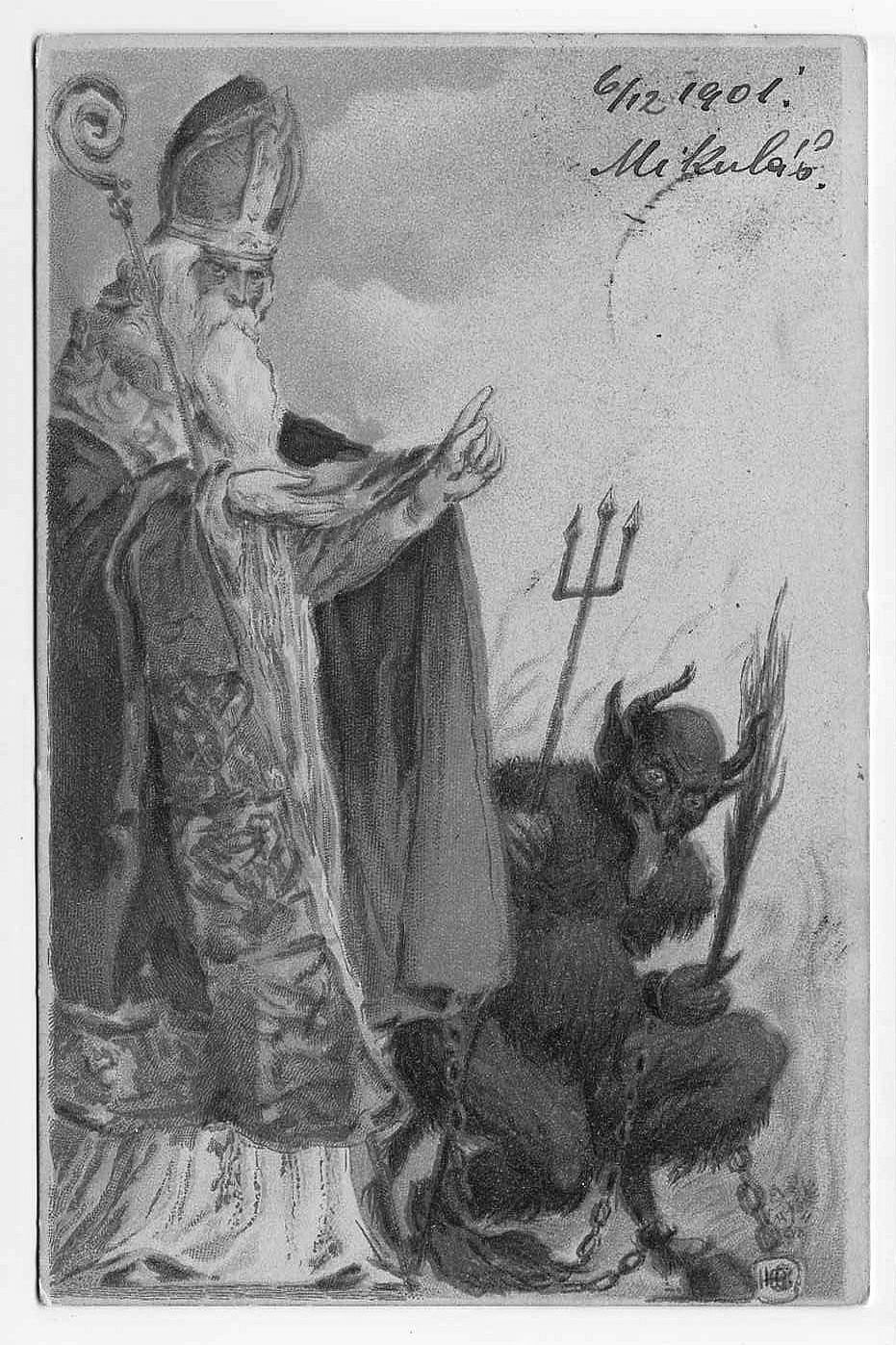

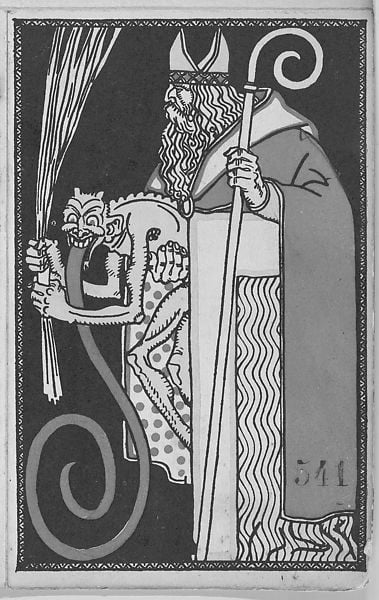

Duality: Saint Nicholas and the Krampus

St. Nicholas is almost always accompanied by a figure that can be interpreted as a tamed devil (blackened and chained, carrying rod and sack). This sinister figure forms a counterpoint to the benevolent and friendly character of St. Nicholas. While one acts as a messenger from heaven, the Krampus is a representative from hell. The children are always rewarded by Saint Nicholas, while his evil companion punishes the disobedient.

Evil punishes evil, but is in the power of good, namely Saint Nicholas.

St. Nicholas and Krampus are usually together. The Krampus, or devil, will threaten the naughty and bad children (and adults) with a rod or take them away in a big chest on their backs. Despite that the Krampus is a frightening creature with heavy chains and loud cowbells, he has to obey St. Nicholas. This fact symbolizes the good triumphing over the evil.

Krampus a descendant of ancient Perchten figures

Advent in Tyrol is not so much the time of silence and reflection.

Rather, it is filled with the noise and romp of the Perchten and similar wild figures. Perchten come for the Rauhnächten (rough nights) just before Christmas at the winter solstice on December 21st to January 6th to drive out the winter and the old year.

Belief in demons and magic gave them the power to banish the evil spirits of winter by ringing bells and wearing ghastly masks. Other features of Perchten parades, like — beating with rods — have possibly to do with old fertility magic.

Saint Nicholas and the demons

Saint Nicholas is closely associated with demons because he was known as an exorcist. The earliest surviving account of Saint Nicholas’s, a hagiography (the lives of saints) written at some point between 814 and 842 AD by Michael the Archimandrite. There are multiple legends about Saint Nicholas defeating and driving out demons.

Sections twenty-eight through thirty of The Life of Saint Nicholas of Myra, describe Saint Nicholas exorcising the demons that haunted the Temple of Artemis at Ephesos. Throughout the rest of the work, the demons banished by Saint Nicholas are described as continually trying to cause harm to him and hinder his work to spread the gospel. Near the end of the work, Nicholas is hailed as “the most active banisher of demons.”

The villagers of Plakoma asked Nicholas to rid a cypress tree of demons. To do so, Nicholas swung an axe, thereby frightening the demons away. St. Nicholas chopped down that tree, giving the demon no place to dwell.

Note: These story comes from Simon the Metaphrast’s life of Nicholas that confused Nicholas of Myra and Nicholas of Sion, blending events of the two saints lives into one. Through it has passed down into the Nicholas of Myra tradition. The story about Saint Nicholas banishing the demons became famous during the Middle Ages. It is likely that this is how he and Krampus first became associated with each other.

Saint Nicholas meets the devil

Another legend of St. Nicholas tells of a time when he was challenged by the Devil. Nicholas was traveling along a lonely road between towns as part of the duties of his bishopric. His horse became bogged down in the mud of the road. The Devil, seeing an opportunity to get the better of the holy man, appeared before him, demanding that Nicholas turn and flee. Nicholas stood fast and ordered the Devil to lead his horse to town in the name of God. This the Devil was forced to do, bound by the saint’s faith.

This explains why Krampus is depicted bound with chains and as a servant of Saint Nicholas; the devil, whom Saint Nicholas has overcome and gained mastery over, has now become Nicholas’s slave, bound to him and bound to obey his words.

The House Visit

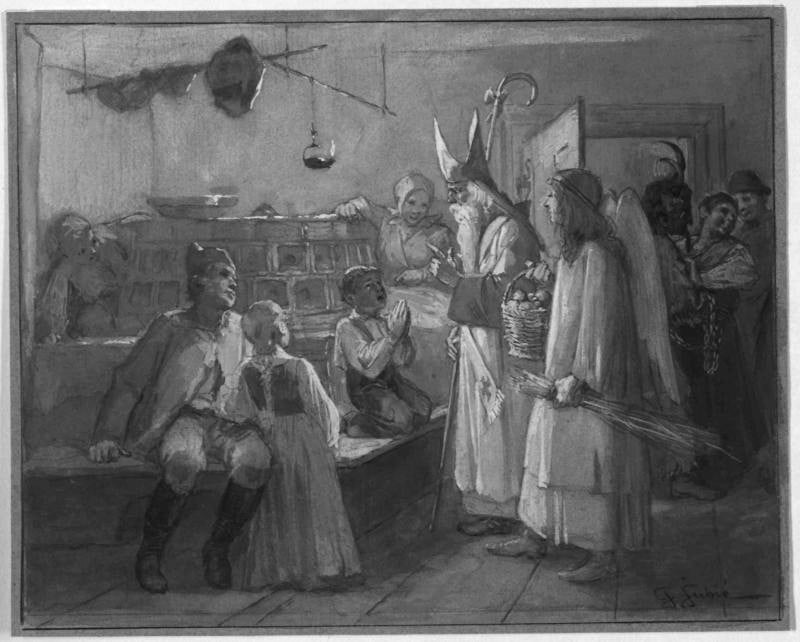

That St. Nicholas visits families and gives children presents is a recent custom. St. Nicholas plays, which used to be performed in farmhouses, are an old Tyrolean tradition.

The house visits, are geared toward children under 10 or 12, and though older teenagers may slip outdoors to run after the Krampus troupes, ideally the whole family, including grandparents, aunts, and uncles, will await the visits.

When the troupe arrives at the house, St. Nicholas usually enters only with his basket-carrier and angels. The Krampuses will wait outside or perhaps come indoors but remain out of sight in a hallway or behind the saint. Nicholas greets the family, introducing himself with a short poem, sometimes handed down from days gone by, but often written by the performer himself. Here is one, in loose translation, penned by Gasteiner Patrick Deisl.

God’s greetings, all within this house!

I’m friend to all, St. Nicholas.

Have no fear, just look at me.

No wild stranger here you see.

My coming marks the year’s near end.

This Forest Man my basket tends.

Deeds good and bad we must review.

With ringing bells comes Krampus too,

What brings him joy brings terror to you.

After his rhymed greeting, Nicholas may hand his staff to a chosen child or one of his angels and open his golden book to review what he knows of the children’s behavior. He likely has just received a few whispered cues from parents as he enters. Or the saint may simply question the children directly and follow this with a few saintly remarks and encouragements.

Now it is time for the children to recite. In the old days, this performance would have involved verses memorized from the Bible or catechism, or sing a hymn, but today more secular material may be used. The children awaiting gifts have been rehearsing for weeks, they recite prayers, poems or sing songs.

Nicholas, Come into Our House

Nicholas, come into our house,

And unpack your big bags.

Merry, merry, tra la la la la!

Today is St. Nicholas night,

Today is St. Nicholas night.

Put your little horse under the table,

So that it eats hay and oats.

Merry, merry, tra la la la la!

Today is St. Nicholas night,

Today is St. Nicholas night.

Hay and oats, it will not eat,

Sugar cookies, it will not get.

Merry, merry, tra la la la la!

Today is St. Nicholas night,

Today is St. Nicholas night.

Niklaus, komm in unser Haus

Niklaus komm in unser Haus,

Pack die großen Taschen aus.

Lustig, lustig, trallerallala!

Heut ist Niklaus abend da,

Heut ist Niklaus abend da.

Stell das Pferdchen unter den Tisch

dass es Heu und Hafer frisst.

Lustig, lustig, trallerallala!

Heut ist Niklaus abend da,

Heut ist Niklaus abend da.

Heu und Hafer frißt es nicht,

Zuckerplätzchen kriegt es nicht.

Lustig, lustig, trallerallala!

Heut ist Niklaus abend da,

Heut ist Niklaus abend da.

As a reward for trials of the Hausbesuch, immediately after their performance kids receive a “Nicholas sack” (Nikolaus-Sackerl) containing assorted treats, typically nuts, apples, mandarin, oranges, figs, dry fruit, candies and chocolates sometimes shaped like little Krampuses or Nicholauses.

Dried fruits might be added, including the particularly old-fashioned “Buck Horns” (“Buxhörndln”), a nickname for the vaguely horn-shaped, sweet-tasting dried pods of the carob tree, which children chew for hours. A related dried-fruit creation is the Zwetschkenkrampus, a little figure of the Krampus crafted from prunes.

Cookies or Lebkuchen (roughly: gingerbread) may also be included and are sometimes baked fresh by the troupe itself. Small Krampus-shaped breads and cookies are also created by commercial bakers and homemakers at this time of year.

Each sack typically must be wrapped in a red cellophane and tied with string to which, a bit of twig or some representation of the Krampus may be attached.

Children who have been naughty are to receive a lump of coal, instead of a gift. The coal I got was black, but made of sugar.

St. Nicholas Day In Austria Aka “Little Christmas” In Austria – Long Version (1934):

Modern house visits

Visits may be offered via a group’s website, social media pages, or newspaper listings, and must be booked well in advance. Sometimes a church-affiliated organization will work with a Krampus group to ensure that a costumed St. Nicholas appears in homes within their parish or diocese.

For these specially ordered visits, instructions are often provided for the family. The “Himmlische Höllenteufel” (Heavenly Hell devils) of the greater Innsbruck area, for instance, suggest parents fill out an online spreadsheet listing various good and bad deeds as a sort of crib sheet the all-knowing Nicholas can tuck into his “golden book” when reviewing children’s deeds.

While officially discouraging the appearance of Krampus alongside the saint (along with threats and lists of bad behaviors), the Archdiocese of Salzburg nonetheless provides guidelines for a somewhat idealized Hausbesuch, featuring hymns, advent wreaths with candles, and edifying talks with children encouraging them to be “little Nicholases.” More practically, they remind families to turn off radios and TVs, and silence cellphones. A final caveat from the diocese:

“Please do not offer St. Nicholas alcohol.”

The Himmlische Höllenteufel, perhaps recalling some unpleasantness between a Krampus and frightened house-pet, request that animals be locked away. They also nix the diocese, suggestion of burning advent candles, no doubt thanks to those luxuriantly furred and flammable costumes.

Traditional Figures of the Krampus Troupe

In most traditional regions of Tyrol, the Krampus troupe is called a “Krampuspass” or, more often, just “Pass.” The Pass consists mostly of men in their late teens to early 40s. Each Pass usually takes the name of a neighborhood, farmstead or family name, geographic feature (mountain, gorge, or boulder), a community landmark (inn or brewery) or professional association or other club (volunteer firefighting associations seem common).

The Krampus

In alpine folklore, he goes by many names, Klaubauf, Kramperl or Tuifl rather than “Krampus.” No troupe would have less than four Krampuses, and more typically the number would hover around six, though more might easily be present. Based on seniority or other outstanding merit, a Vorteufel (“head devil”) is usually appointed to be the first to enter and leave homes and otherwise help Nicholas control his pack.

Krampus come in many shapes and sizes, the costume consists of leather boots, a full bodysuit of leather and fur, leather or fur gloves, and leather belts with giant bells to make noise as the Krampus walks. Most wear also wooden masks, lolling snake-like tongues, with two to four animal horns. The Krampus attire can weigh up to 30 kilograms or 66 pounds.

Krampus masks Holzlarven in German, are typically hand-carved from stone pine wood — and they are the products of significant labor. Goat, cow or Steinbock (an Alpine mountain goat) horns, Ibex horns, antelopes or replicas are used to decorate the heads. Some of this beautifully decorated masks, are over 100 years old. In the past, the Krampus sometimes had a comical expression, but in modern times realism has triumphed. The mask’s face is even frequently lacerated and bloody, and sometimes LED lights are incorporated to make the eyes glow.

Artisans often work for months on the costumes, which sometimes end up on display in museums as examples of a living tradition of folk art.

Their bodies are covered in skins or fur of goat, sheep, cow, bear, which often exudes an intoxicating scent. Fox and marten skins and even yak or horse tails are used for the costumes. Perchten wear straw or goat clothing and for the Klosen it is colorful cotton costumes and with heavy cowbells attached to their belt.

A bundle of willow or birch rods and soot are also part of the basic equipment and the Krampus makes a hell of a noise with bells and rattling chains.

Black faced Krampus

Under their masks, Krampuslauf participants still blacken their faces, obscuring not only the visible area around the eyes, but also blackening the entire face whether visible or not. In Sterzing/Vipiteno, Southtirol some Krampus troupes do not wear masks and have blackened faces.

Black faced Krampus at Tuifltog Sterzing. Courtesy of Southtirol-Ratschings.info

Krampus face may be blackened with ashes, or he may even carry a bag of ashes with which to thump the unruly and leave a telltale mark (just as in some areas of the Tyrol, the Krampus smears victims with a mixture of lard and ashes).

It may have been associated with the sooty visage of the local blacksmith who worked in a fiery environment itself evocative of the Devil. Blackened faces are a common way of obscuring the faces of Christmas player throughout Europe, and in the case of some traditions, the performers, anonymity was essential to the magical luck imparted by visiting mummers.

Other theories suggest that faces were blackened because these figures represented the dead traveling in the winter nights.

There are no limits to imagination: you can find everything from ancient wooden masks to modern devil costumes with glowing eyes.

Bishop Nicholas

The Nicholas costume, resembles that of a medieval bishop, complete with miter, and crosier; a tall pointed hat and a hooked staff carried by a bishop, represents a shepherd’s staff as the bishop is to be the shepherd of the people. His beard and wig are invariably theatrically and impossibly white and voluminous.

In years gone by, Nicholas would also sometimes appear as a masked figure. Though this practice has largely disappeared, a few modern mask-carvers today are now extending their offerings to include these old-fashioned, intimidatingly impassive Nicholas masks.

Though he always wears a white gown, the overlaying chasuble can vary in color. Red, or sometimes gold, green, blue, purple, and other colors are used. Nicholas also always carries a large Bible-like “golden book” from which he may “read” of children’s good and bad deeds during his appearance as previously mentioned.

A last feature of the costume would be some sort of bag or purse in which Nicholas collects donations from families visited. Though there is never a set fee demanded, a typical donation might be around 10-15 euros or dollars.

In the old days, the Pass would get a cut of bacon or a bottle of Schnapps or something like that. Even today a few households may provide some snacks or beer, making them popular stops on the troupe’s routes.

The Basket Carrier

The roles in troupes are dictated by the needs of the all-important Hausbesuch. A product of this is the Körblträger or Körbler, basket carrier, a figure increasingly rare. On his back, he wears a large basket woven of thin wooden splints in which he carries small treats for the well-behaved—not an insignificant task as the full load can weigh over 45 Kilograms or 100 lbs, and the basket may be refilled one or more times throughout an evening’s run. The Körblträger may also be called a Guazltrager (“sweets carrier”) or Waldmandl forest amn. In the Alps, a Körblträger is packing a nice array of schnapps bottles deftly stuffed between the gifts.

The Angels

The Engerl or Engel (angel) typically appear alone or as a single pair, though larger troupes may have more. They carry small baskets filled before they enter each home, with that family’s portion of treats fished from the Körblträger’s load. As the basket-carrier is actually a rare figure elsewhere, the angel in many places takes over any gift-bearing duties altogether, and in even smaller groups with no angel, a Krampus may be the one to carry a sack of gifts.

The angel generally wears a small crown and the long white gown you would expect, albeit a tad bulkier thanks to layers of warm clothes. Crowns, wings, veils, or blonde wigs may be added, and in less tradition-bound areas, there is a nod to fashion with shorter skirts or even red- or black-wardrobed “gothic” angels.

The Krampus Run versus the Saints House Visit

Unlike other regions where the Krampus appears as an adjunct to weeks-long Christmas markets, in more traditional places, the “devils” only appear on December 5 and 6. Activity on the 5th then revolves around the town center, and on the 6th involves the Krampus visiting outlying farmsteads with St. Nicholas. Children and families are visited in their homes where the saint assays behavior and delivers small gifts, while the Krampus puts on frightening displays. The house visit is a hallmark of activity.

The connection to the saint is much more than a formality of date. Unlike less traditional places, where Krampus packs may roam the streets unattended by any saint, in villages, each troupe has a costumed Nicholas as leader.

And unlike other cities with large runs, where the Krampus may merely strut his stuff, brandishing switches and perhaps swatting a few adults along the way, the carrot-and-stick role of Nicholas and his punishing assistant is taken seriously. Elsewhere it exists, but is largely being supplanted by performances in public spaces or runs.

The “run” in villages merely consists of troupes moving from house to house, following their own individualized routes. While it’s no organized parade, there is some effort by groups to at least pass somewhere in the center.

Outside traditionalist regions, and certainly in more urban areas where families don’t live within walking distances, the Hausbesuch, is not incorporated into the general house-to-house Krampuslauf, but is a specially arranged event, sometimes attended by a smaller portion of the entire troupe. This groups assemble in the afternoon to begin runs that can last all night.

A mangled, deranged face with bloodshot eyes tops a furry black body. Giant horns curl up from his head, displaying his half-goat, half-demon lineage. Behind this terror, a dozen more stomp through the snow of the streets of Tyrol, among a din of cowbell jangles.

The creatures dash through the streets, chasing giggling children and adults alike, poking them with birchsticks and scaring some with the realization that they were naughty this year.

~Jennifer Billock, smithsonianmag.

The Krampuslauf — Krampusrun, Devilsrun or Krampusnight

The traditional “Nikolaus- and Krampusumzug” (St. Nicolas parade) takes place every year on December 5. As in many parts of Tyrol in Austria, southern Bavaria and South Tyrol, on this day, St. Nicolas appears in devilish companion on the streets. After the house visit, in the afternoon, the group would parade to the center. While Saint Nicholas rewards the well-behaved children with gifts, Krampus — in contrary, punishes naughty, bad-behaved children.

During the Krampuslauf (Run Parade, Krampusnight or Krampusrun), a spectacle late afternoon or at night, costumed Krampuses appear in the streets, terrifying child and adult alike — yelling, roaring, whipping the legs with birch brooms and/or smearing their faces with a mixture of sooth and grease.

While the majority of Krampusse seem content to harass the crowd on foot, some ride in large carts or vehicles, shooting flames or bellowing smoke.

My granny told me:“The secret weapon against the devil are prayers”. The Krampus will not hurt children,

if they recite loud and clearly the Lord’s Prayer or the Ave Maria!

If you cannot recite prayers, being caught by a Krampus is a rather violent affair. They carry birch switches that they use to deliberately lash at people’s thighs. When there is snow, they also like to knock people over and rub snow in their faces.

Particularly tough guys, meet for the “Tuifeltratzen”, bedeviling — they deliberately approached the Krampus, provoke them and then all depends on who can run faster — Krampus or the young boys. Frequently, these tests of courage end with loud cries, laughs, a beating and sooty faces for the youngsters.

The terrifying masks hide the friendly faces of young villagers, and while tradition used to dictate that only male bachelors could be Krampus, some Krampus troupes now include women.

The Krampus tradition has become so popular that it has spread beyond its traditional Tyrolean roots to some towns in eastern Switzerland, where it is called Schmutzli, as well as the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovenia, and even the United States, where Krampuslauf are periodically held in Los Angeles, Philadelphia, and Bloomington, Indiana.

The Krampus parades in Tyrol

Graz (East Tirol)and Salzburg are known for large parades. Not far across the Austrian/German border Munich is also noteworthy for drawing international tourists and costumed groups from across the Krampus homelands.

The oldest Krampus run in South Tyrol takes place in Dobbiaco/Toblach in the Upper Val Pusteria and Vipiteno/Sterzing. Every year, more than 600 Krampus meet there.

Whereas the Krampus must obey St. Nicholas in former times, the Krampus parades today are majorly just for the Krampus. In the Alps, many villages and cities organize Krampus parades, some with over 1000 Krampus. In modern times the Krampuses greatly outnumber the St. Nicholauses.

Some of the oldest Perchten parades (with St. Nicholas) take place each year in Gastein (Austria- Tirol) and Krampus parades in Toblach (Southtirol).

Big parades are also held, with more than 50 groups from Austria, Germany, Switzerland and Italy. Procession with elaborately designed cars, pyrotechnics, fire shows and loud music make the whole thing an impressive spectacle.

Since the Krampus sometimes showed themselves a bit too wild in their hustle and bustle, today everyone who takes part in the show as a Krampus is registered and has to wear a number plate. Schnapps is traditionally given to all the participants.

Meeting the mythical Krampus in Tyrol

All in all, a run parade event provides an exciting, mythical, and a memorable experience for people in East- and North Tyrol (Austria), and South Tyrol (Italy), in Christmastime.

The Alpine devil is visceral and physical in a way that few figures are. Smelling of animal hides and wet snow, he pushes forward assaulting your ears with his bells, shoving through spectators with a force unknown in polite society, and then, of all things—he hits you!

The writer, Michael Karas of The Record newspaper in New Jersey, writes:

“While being relentlessly pursued through the snow by a horned beast dead set on punishing the wicked may seem like an unorthodox path to embracing the holiday spirit, the lashings were an immediate catalyst for introspection, after which I found myself silently promising to become a better person in the new year.”

The devil hits us, and whether we laugh or scream, at least we are now truly awake, experiencing the real world fully, and standing before a myth.

Perchta and her Perchten

Moreover, with these runs there also came other mythical figures featured such as the Perchten (Tirol, Austria). The Pertchen are wild winter spirits of Alpine folklore that become celebrated around December, the same time as the Krampus, but usually around winter solstice. This class of spirits is divided into two species, the good or “beautiful” Schönperchten, and the bad or “ugly” Shiachpercht, the latter being, naturally Krampuses. They obey a woman, her name is Frau Perchta.

The “beautiful” Schönperchten, and the bad or “ugly” Shiachperchten

The word Perchten is plural for Perchta, and this has become the name of her entourage, as well as the name of animal masks worn in parades and festivals in the mountainous regions of Austria. In the 16th century, the Perchten took two forms: Some are beautiful and bright, known as the Schönperchten (beautiful Perchten). These come during the Twelve Nights and festivals to “bring luck and wealth to the people.”

The other form is the Schiachperchten – ugly Perchten, who have fangs, tusks and horse tails, which are used to drive out demons and ghosts. Men dressed as the ugly Perchten during the 16th century and went from house to house driving out bad spirits.

Sometimes, der Teufel, the Krampus is viewed as the most schiach – ugly and Frau Perchta as the most schön– beautiful Percht.

Frau Perchta

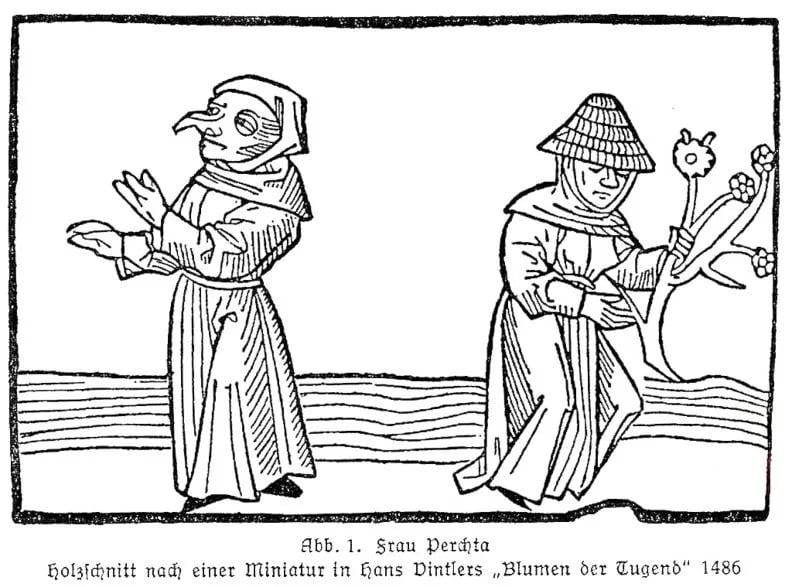

The very first illustration we have of Perchta seems to show not the figure herself, but in fact a masker. In South Tyrolean poet Hans Vintler’s 1486 Die Pluemen der Tugent (The Flowers of Virtue), various superstitions are derided, including a belief in women like “Percht with the iron nose.” Perchta’s long or beaklike nose is a characteristic feature, and is often described as being of iron (as are, sometimes, her hands, teeth, and warts.)

Perchta is beautiful otherworldly matron whose name evokes purity and light. To this day, Alpine folklore paints Perchta, as a monstrous being, eating, tearing asunder, or disemboweling those who displease her. This shape-shifting Christmas woman even fills disobedient children’s bellies with straw.

A Hexe witch—though she’s also called a goddess—is a figure known primarily in Austria and Bavaria as Frau Perchta. Her name, associates her with the Perchten, Alpine spirits, as prototype for the Krampus. She goes by Pehrta, Berchte, Berta, and other related or regional names. Like the Perchten, Perchta is a creature of dualities, and makes her rounds on appointed winter nights to both reward and punish according to deed.

From Perchta to Perchten

The first mention of Perchta appears around 1200, but the word “Perchten” is not employed until centuries later. In 1468, there appears a reference to her companions. At this stage in Perchta’s mythology, the company she leads is most often understood as spirits of the departed.

With time, Perchta’s pagan company came to be commonly feared not as ghosts but as demons, something presumably closer to the horned figures we now know. It’s here, via Frau Perchta’s horde, that we find a connection between the Krampus and the souls of the dead. This is the connection hinted etymologically by the Bavarian “Krampn” (“lifeless” or “shriveled”) some believe to be the source of the Krampus name.

Frau Holda

In Germany, north of Bavaria, Perchta’s counterpart is Holda (also Holle, Hulda), identified from the 12th century onward by concerned churchmen like Burchard of Worms as the leader of an infernal horde. Martin Luther seemed to know her as a grotesque mumming figure, referencing in one of his sermons a weird “fraw Hulda,” characterized by a long snout, rags and “straw armor.”

Just as Perchta’s association with agriculture is represented by her plough in the tale of the ferryman, even more stories emphasize Holda’s connection to nature and the fertility of crops, animals, and humans. Her passage over a farmer’s land was said to ensure a bountiful harvest. She is also strongly associated with the life-giving waters of springs, ponds, and streams, and is sometimes spotted in the noonday sun near bodies of water, dressed in shining white and only visible for an instant before vanishing.

Syncretism of Perchta and Holda

Jacob Grimm, and in his Deutsche Mythologie, is pointing to Perchta’s virtual identity to the pagan figure Holda. Grimm’s efforts to connect the medieval Holda (and consequently Perchta) to the ancient Germanic goddess Frigg/Freya are today viewed with skepticism. Even the term “goddess” Grimm and countless others have used to describe her might be questioned.

Perchta and Holda are often assumed, to be ancient goddesses worshiped by early Germanic or Celtic tribes. Romanization of Celtic settlements in the Alps had already begun at the dawning of the Common Era, with Christian missionaries arriving and beginning conversion of the area by the 2nd century. Germanic tribes entering the areas had already converted by the 5th century. With the first mention of Holda-Perchta in the written record not occurring till around the year 1200, we’re left with approximately seven centuries of Christianizing influence and intermingling of beliefs, making any precise equations with older, more pristine forms of Celtic or Germanic paganism questionable.

Depending on context, both Perchta and Holda might just as well be regarded as guardian spirits associated with a particular place (a mountain or spring) or with protected persons (children, women). Perchta is primarily associated with the end of the year.

The customs associated with her are largely those imagined by the Church in the traditions of the Krampus and Nicholas.

Perchta is, in this sense, the root from which it all grows.

Gastein Perchten

In 2011, the Gastein Perchten were included in the UNESCO World Heritage List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Tirol, Austria. In Gastein, roughly 140 figures participate in the run include the “ugly” Shiachpercht, like Frau Perchta and her Perchten and devils, buffoons, grinders, witches, bears and bear hunters, Moors and Turks; but also “lovely” Schönperchten, like the Three Kings and about 30 “cap-wearers”, who wear headdresses often several meters high. The troupe wanders with the Perchtenmusik, playing traditional Alpine music in ¾ tact.

The Perchten wear thick plant fiber suits with enormous bells or drums. They gather around a lead Krampus who tends a mystical fire and directs them while they drum in a circle around the fire. Perchta is accompanied by the lead Krampus, but St. Nicholas makes no appearance.

5. + 6. Dezember Perchten in Kufstein, Tyrol:

Klosen

“Klosen” in the old mining village of Stelvio/Stilfs (Southtirol) in the upper Vinschgau valley is one of traditions most shrouded in mystery. Probably it is an ancient pagan fertility rite that is performed to chase out the winter and revive the reproductive power of nature and humans.

St. Nicholas Day falls on 6th December and on the preceding Saturday three groups of 20 year-old young men congregate to take part in an outlandish custom. They are called “Scheller” (bell-bearers) or “Esel” (donkeys) disguised in motley-colored rags, terrifying masks and heavy bells. Attached to belts, they carry several bells as large as they can handle. They make as much din as possible, imitate donkey braying and now and again roll around on the ground. In this disguise they roam noisily through the streets. St. Nicholas joins the queue too. He is accompanied by four wise men clothed all in white and he isn’t impressed at all by the hustle and bustle, but just calmly follows the parade.

Klosen in Stilfs/Stelvio:

A short moment of quiet is granted in the evening during the Hail Mary tolling. Afterwards, the loud and funny “Klosn Festival” with food, drinks and music will last long into the night.

Klaubauf

In the Alps St. Nicholas was accompanied by a certain Krampus named Klaubauf who did the saint’s bidding. His name comes from “Kalub auf!” meaning “Pick’em up!”, the command he gave as he threw treats of apples and nuts to the children.

The appearance of the famous Klaubauf masks from Matrei in Osttirol changes from generation to generation.

HISTORY: On the Krampus

The mythological explanation imagines the origin of Krampus as an ancient pagan fertility rite that was performed to chase out the winter and revive the reproductive power of nature and humans.

The history of the Krampus figure has been theorized as stretching back to pre-Christian Alpine traditions, with celebrations involving Krampus dating back to the 6th or 7th century CE. Though there are no written sources before the end of the 16th century. The active Krampus convictions about the pre-Christian roots of this custom resulted not only from locally passed down knowledge, but from an origin story deliberately disseminated by folklorists in the early twentieth century.

On the origins of the Krampus

According to recent scholarship, folklorists were inspired by the proto-fascist ideology of German nationalism. Viktor von Geramb, Richard Wolfram and others, were convinced that the masked rites were the remnant of a Germanic custom that had been “moulded” (überformt) by Christianity. One of the main aims of National Socialist folk studies, then, was to remove this imagined Christian layer. This right-wing agenda was never backed up by serious historical research, and even after the fall of Nazi Germany it took decades for this to happen.

In the 1980s the ethnologist Hans Schuhladen did start to work systematically through the historical records. He found no pagan origins for the Percht (Krampus), and his earliest source is modern: in 1582, in the Bavarian town of Diessen, those who had “hunted the Percht” received a monetary reward. Unfortunately, there are no details of the sequence of the rite or the costumes.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, reports from Bavaria, Tyrol and Salzburg abounded; however the word Krampus, is absent from all of these historical sources, which all use Percht instead to name the practice.

The word Percht is commonly associated with the old deity Perchta, the Perchtenlauf is most probably a proto- Krampuslauf.

Carnival Parades

Only with the advent of Romanticism and its different attitude towards the peasantry and its culture, did descriptions appear. Judging from these sources, the old Perchten runs were carnival parades. In the months between Advent and Candlemas there was comparatively little work to do in the Alpine peasant economy, so young people gathered in the main households in the villages and the pantries were full.

In this vein, in 1841, Ignaz Kürsinger wrote that:

The Perchten customs belong to the winter joys of the highlander, comparable to the balls and theatre performances of the city dwellers.

~ Schuhladen 1992.

The Moving theater in Tyrol

The “Saint Nicholas plays”, show the appearance of the “holy man” in a dramatic way. A distinction is made between actual Saint Nicholas plays and so-called sub-comedies or moving theater in Tyrol, where small groups, mostly comprising St. Nicholas, a devil and an angel, went from house to house, and performed small theatrical pieces with blessings.

Tyrolean Saint Nicholas plays

Ulrike Kammerhofer-Aggermann refers to the Bavarian and Tyrolean Nicholas plays that emerged from the Jesuit plays of the Counter-Reformation, arguing that in the nineteenth century these often escalated into wild parades, that were only called Perchten runs later.

The spiritual drama, or “Nikolausspiele” developed in part from the moving theater and peasant comedies. The are entirely in dialogue form, performed by companies and are characterized by delicious humor and wit.

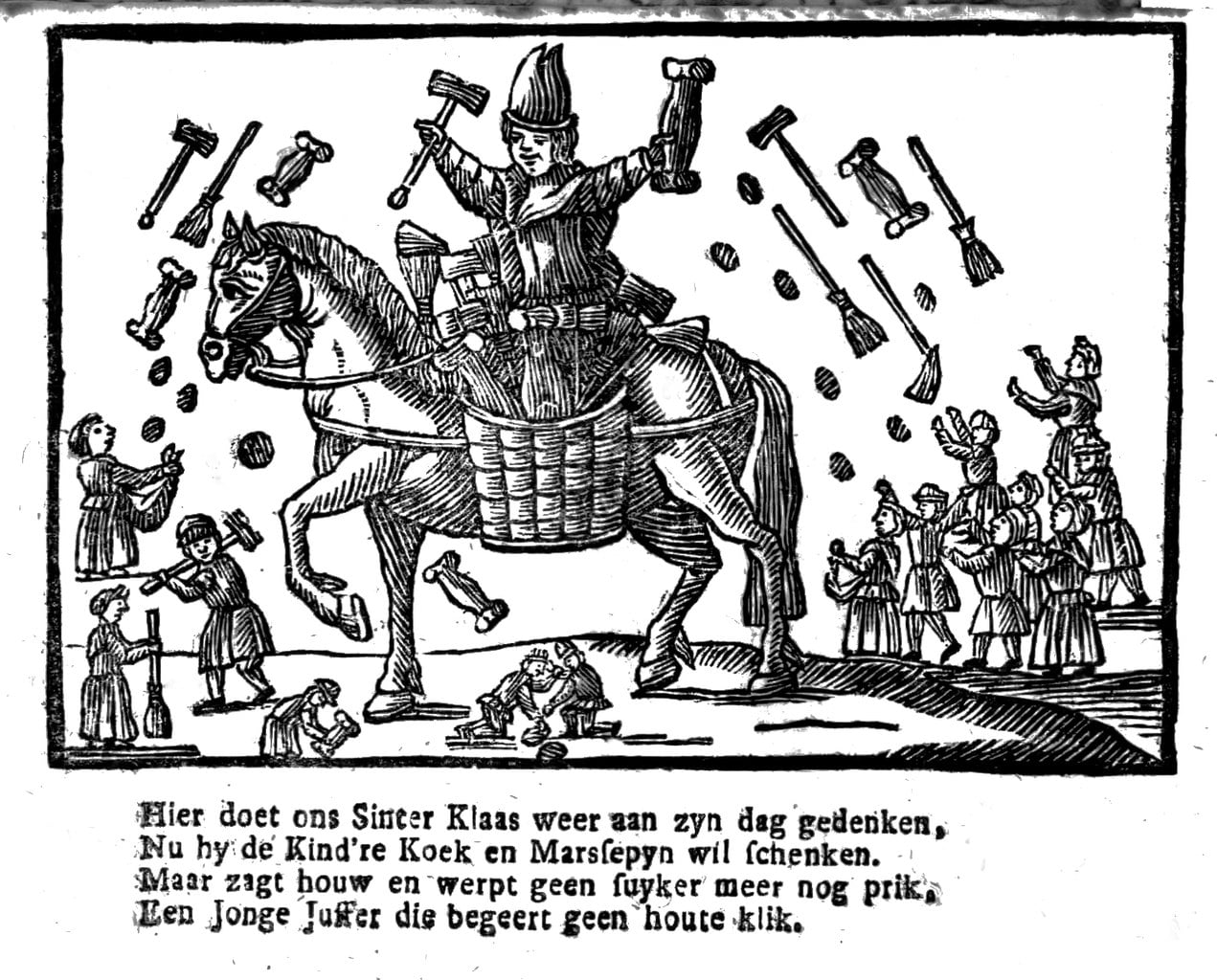

The troops, often thirty or forty strong, move from place to place; the scene of the representation is usually the village square. The material is borrowed from the legend, but overgrown with all sorts of non-spiritual accessories. And spiced with hilarious comedy. St. Nicholas appears ahead on a gray horse or donkey, laden with gold and tinsel. He solemnly announces his arrival in high-pitched rhymes.

Behind him comes on horseback and on foot an adventurous retinue of shepherds, hunters, hermits, Moors, Turks, oil carriers, the “three holy kings”, witches, gypsies, villagers; in addition there are quacks, clowns, angel and devils.

The Counter-Reformation is important for two reasons. First, there is ample evidence that the depiction of the devil in the Tyroleantheater was a direct predecessor of the Krampus.

Secondly, it was in the aftermath of the Counter-Reformation, in the 1730s, that Archbishop Leopold Anton von Firmian of Salzburg expelled the remaining Protestant population from his territory.

The vacated farms and miners houses were taken over by Catholic migrants from Tyrol, thus reinforcing the influence of the Tyrolean Nicholas customs in the area.

Along with regionalism, the Protestant/Catholic divide has been a historic factor in diversifying the tradition of the Krampus and Saint Nicholas.

Protestant Reformation and Martin Luther

Martin Luther (1483-1546), is a German priest, monk, and theologian who became the central figure of the religious and cultural movement known as the Protestant Reformation.

Protestantism rejects doctrines of the Catholic Church, like the indulgence system, which in part allowed people to purchase a certificate of pardon for the punishment of their sins. Apostolic succession, the infallibility attributed to the pope, and the equating of the authority of church teaching and tradition with the bible was also rejected.

For spiritual wisdom, one should be referring directly to the Bible, the Christian holy book. Martin Luther’s translation of the Bible into the language of the people gave the protestants the possibility to find god without intermediaries.

Protestant Christianity contends that, according to the Bible, all believers are “saints,” whether they are alive on the Earth or in heaven. Protestantism rejects the notion that the term “saints” only refers to those people who are particularly holy, who the Catholic Church has recognized.

The Counter-Reformation describes the Catholic Reformation or the Catholic Revival, and was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation.

The Carnival of Venice

As Ulrike Kammerhofer-Aggermann has convincingly argued. Her historical research shows that the carnival in Venice was a significant point of reference, and places where the Krampus still roams are located along important trade routes, running through Tyrol, connecting southern Germany with Venice.

Other evil companions to St. Nicholas

Krampus isn’t the only demon who casts a menacing shadow over children who haven’t toed the line during the year. Other Parts of Europe have different figures to worry about.

Zwarte Piet

In Flanders (the Netherlands), Nicholas was followed by the black-face

d and horned Zwarte Piet or Black Peter. Although Black Peter was sometimes made to look like a Moor, he personified the Devil. He was established in the Netherlands as the Sinterklaas helper in the 1845 book Sinterklaas en Zijn Knecht. He rides over the rooftops with Sinterklaas, listens down chimneys to check children’s behavior, and delivers gifts.

Piets are enormously popular; the Dutch see them as more fun-loving and mischievous than the more stately bishop. Besides, the Saint asks children questions and gives fruit while it is the Piets who hand out treats and candy. Piets are also found in Belgium.

Hans Trapp

Alsace and Lorraine regions of France and Germany knows Hans Trapp. According to legend, he lived in the 1400s; a rich, powerful knight, and merciless man who was feared by the people. His thirst for power was so great that he turned to deals with the Devil to enhance his power and status.

One story, in particular, describes an instance in which Hans Trapp stabbed a child, sliced him into tiny pieces, cooked and ate his flesh!

Knecht Ruprecht

In some cases, Krampus has taken the place of Knecht Ruprecht, who accompanies Saint Nicholas. Germany’s Knecht Rupercht, a black-bearded man who carries switches with which to beat children.

There are many different characters: Krampus in Southern Germany, Pelzebock or Pelznickel in the North-West, Hans Muff in Rhineland, Bartel or the Wild Bear in Silesia, Gumphinkel with a bear in Hesse, Buttenmandl in Bavaria, or Black Pit close to the Dutch border. In the Palatinate both Nicholas and his attendant may be known as Stappklos, the plodder and grumbler.

Buttenmandl and Gankerl

Usually wrapped from head to toe in hand-threshed straw, the Buttnmandl run noisily from home to home and through each community during the pre-Christmas season in Berchtesgaden, Bavaria.

Their heads covered with a fur mask and a long red tongue adding to their frightening appearance, they clank the large cowbells attached to their backs.

Instead of straw, Gankerl or Krampus, are clad in fur from head to toe as they accompany their straw brothers, all the while flicking switches at the legs of young girls in possibly a sign of fertility. Their mission is also to chase away evil spirits at the dark time of year (near the winter solstice) and to awaken Mother Nature slumbering deep under the hard frozen ground.

Rosenhofer Buttnmandl und Gankerl- Berchtesgaden Nikolaus.

Pere Fouettard

Depicted in a similar vein there is Pere Fouettard, by comparison, though, he is seen as more of an “assistant” to Saint Nicholas, punishing those have been bad during the year whilst he hands out presents to the others.

He is found in France and Luxembourg, where he’s known as Housécker. His name doesn’t translate well, but means “Mr. Bogeyman,” “spanking,” or “switches.” The evil butcher was forever condemned to follow St. Nicolas as a punishment for luring lost little children into his shop.

The older, original version of this story is about three students traveling away to school. They stopped in an inn and were drugged, robbed, and murdered. Over the years, these grown male students came to be seen as little children. Sometimes it is an evil innkeeper, other times an evil butcher that does them in.

Schmutzli

Schmutzli – Santas alter ego

Schmutzli is nearly all brown: dressed in brown, with brown hair and beard, and a face darkened with lard and soot. He is St. Nichola’s helper in Switzerland. Children used to be told that Schmutzli would beat naughty children with the switch and carry them off in the sack to gobble them up in the woods. Today there is little talk of beatings and kidnappings.

HISTORY: On St. Nicholas

Nicholas’s existence is not attested by any historical document, so nothing certain is known of his life except, that he was probably bishop of Myra in the 4th century. Myra is in Anatolia, modern Demre, Turkey.

Hagiography of Saint Nicholas

According to tradition, the saint lived circa 260-333 CE, he was born in the ancient Lycian seaport city of Patara. He traveled to Palestine and Egypt. After his parents died, Nicholas is said to have distributed their wealth to the poor.

Soon after returning to Lycia, he became bishop of Myra (modern Turkey’s Demre), part of the Byzantine Empire.

Nicholas was imprisoned and likely tortured during the persecution of Christians by the Roman emperor Diocletian, but was released under the rule of Constantine the Great.

Nicholas may have attended the first Council of Nicaea (325), where he allegedly struck the heretic Arius in the face. He was buried in his church at Myra, and by the 6th century his shrine there had become well known.

In 1087 Italian sailors or merchants stole his alleged remains (relics) from Myra and took them to Bari, Italy; this removal greatly increased the saint’s popularity in Europe, and Bari became one of the most crowded of all pilgrimage centers.

San Nicola’s relics remain enshrined in the 11th-century basilica of San Nicola at Bari, though fragments have been acquired by churches around the world.

Face to face with San Nicolo di Bari

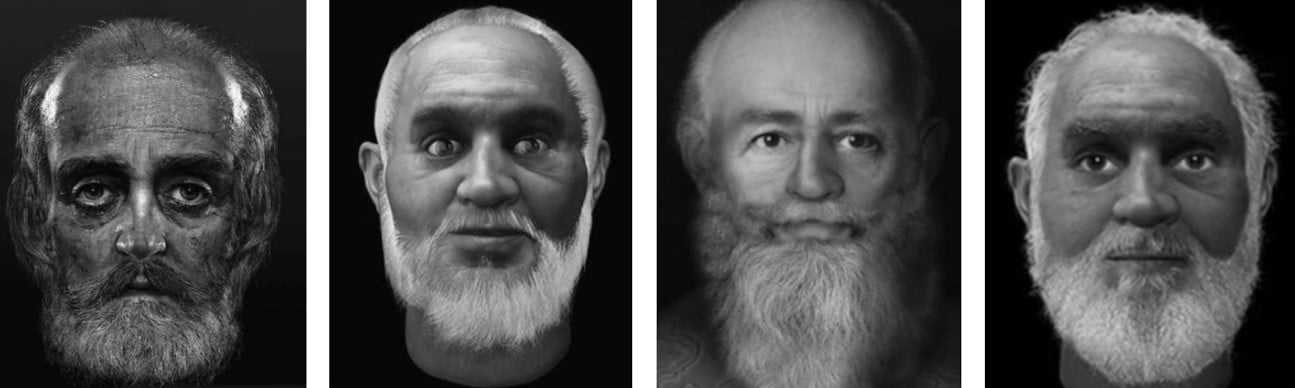

The relics in Bari and Venice have been analyzed and researchers used a facial reconstruction system and 3D interactive technology to create a portrait of St. Nicholas. He had a round head, heavy jaw and a broken nose, that healed asymmetrically.

Left to right: Digital reconstruction Deisis Project, Russia, 2004; Forensic Reconstruction, Anand Kapoor- Foundry studios, 2004; Liverpool John Moores University’s Face Lab, 2014; Forensic Reconstruction, Anand Kapoor- Foundry studios, 2020.

Based on the broken nose in the saint’s facial reconstruction, maybe Arius punched him back.

LEGEND: St. Nicholas and the dowry for the three virgins

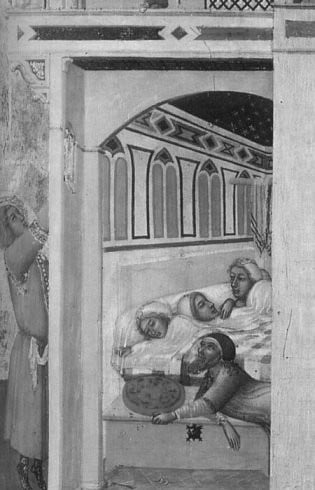

This story is first attested in Michael the Archimandrite’s, Life of Saint Nicholas:

Nicholas heard of a devout man who had once been wealthy but had lost all of his money due to the “plotting and envy of Satan.” The man could not afford proper dowries for his three daughters. This meant that they would remain unmarried and probably, in absence of any other possible employment, be forced to become prostitutes.

Hearing of the girls” plight, Nicholas decided to help them, but, being too modest to help the family in public (or to save them the humiliation of accepting charity), he went to the house under the cover of night and threw a purse filled with gold coins through the window opening into the house.

The father immediately arranged a marriage for his first daughter, and after her wedding, Nicholas threw a second bag of gold through the same window late at night.

After the second daughter was married, the father stayed awake for at least two “nights” and caught Saint Nicholas in the same act of charity toward the third daughter. The father fell on his knees, thanking him, and Nicholas ordered him not to tell anyone about the gifts.

The scene of Nicholas’s secret gift-giving is one of the most popular scenes in Christian devotional art, appearing in icons and frescoes from across Europe.

6. December is Saint Nicholas day

The Feast of Saint Nicholas is observed on 6 December in Western Christian countries, and on 19 December in Eastern Christian countries using the old church Calendar. The feast day of Saint Nicholas of Myra falls within the season of Advent.

December 6 is the day St. Nicholas died — saints days always commemorate the day of death, or entrance into life eternal.

By the eleventh and twelfth centuries the saint evolved from a rather severe figure of a bishop, to the compassionate children’s friend, giving gifts on St. Nicholas Day.

As early as 1163 it was observed in Utrecht, the Netherlands. During the same time span, 12th century, French nuns began leaving candy and gifts outside the doors of children in need. The St. Nicholas Day children’s gift-giving custom spread through Germany, Austria, France, Switzerland and England. It took root across most of northern and central Europe, as far east as Romania.

Nicholas primary virtue came to be seen as generosity to children—rooted in the stories of rescuing the desperate maidens with gold for their dowries and of saving three children or schoolboys from an evil fate. Legend has it, that he resurrected three children, who had been murdered and pickled in brine by a butcher or inn owner, planning to sell them as pork during a famine.

In the early Middle Ages, children’s gift day was the feast of the Holy Innocents (December 28). As St. Nicholas became popular and the patron saint of schoolchildren and children, in the 13th century the day of giving gifts for boys shifted to the feast day of St. Nicholas (December 6). In the 14th century, December 6th is generally accepted as the date of gifts. In some places, the feast of St. Lucia (December 13) seems to have become the children’s gift day for girls.

15th century Swiss writer Hospinian wrote:

“it was the custom for parents, on the vigil of St Nicholas, to convey secretly presents of various kinds to their little sons and daughters who were taught to believe that they owed them to the kindness of St Nicholas and his train, who, going up and down among the towns and villages, came in at the windows, though they were shut, and distributed them.

This custom originated from the legendary account of that saint having given portions to three daughters of a poor citizen whose necessities had driven him to an intention of prostituting them.”

The house visit described was a well none custom at the time.

St. Nicholas Eve — The night visit

The good old white bearded man, miter on head, and pastoral stick at hand, in some places brings gifts in the night between December 5 and 6. This is a modern tradition (about 300 years old) found in some Tyrolean households.

Families will leave him salt for the donkey, a glass of Grappa/Schnapps (a strong distilled fruit brandy), and a saucer with white flour that the saint will use to cover his footprints in the snow.

The Custom of the Shoes

Other traditions include doing a deep clean of the house, on 5th December to prepare for St. Nicholas arrival. The shoes are also polished thoroughly to give and receive the offerings.

Children put carrots, turnips, or hay in their shoes for St. Nicholas horse or donkey. This shoe is then magically filled overnight with chocolate and sweets or even money. It is much like the tradition of hanging stockings up on Christmas Eve for it to be filled with gifts in the morning.

Children will leave the shoes near a fireplace, on the windowsill, at the front door or near a bedroom door.

This tradition is predominantly seen in European and Eastern countries with a strong Catholic following.

This tradition grew from the story of when St. Nicholas, the Bishop of Myra, threw bags of dowry money, either through a window or down a chimney, into the home of an impoverished family to rescue their daughters from being sold into slavery. (St. Nicholas and the dowry for the three virgins) This was just one of his many acts of good will and charity towards the poor, especially poor children.

Legend has it that one time the gold apparently landed on some winter shoes and stockings that had been laid out near the fire to dry. This led to the tradition of children putting out shoes or stockings at night for Saint Nicholas to fill with gifts.

The “laying” of gifts

The “laying” of the gifts, German Einlegebrauch, is probably derived from the legendary “laying” of the gold nuggets in the house of the three girls. According to one story, the gold thrown/inlaid through the window, or later, the fireplace got caught in the girls stockings that were hung up to dry there. Even Martin Luther practiced this in his family until 1535.

It was in this era, as well, that Nicholas mode of entry shifted from windows and doors to chimneys. There were no chimney’s in Lycia when Nicholas lived—they simply did not exist and most cooking took place outdoors. Chimneys, appeared in colder Europe during the 13th century. Art from that time begins to show Nicholas charity being delivered via chimney, rather than window.

In the Anglo-Saxon sphere of influence, stockings or shoes are therefore common “receiving containers” – smart children also use more voluminous boots for this reason.

Ludus episcopi puerorum

A common ecclesiastical practice was to elect a “boy bishop” (Episcopus Puerorum) to hold office from the Eve of St. Nicholas, Dec. 5, to Holy Innocents, 28.December.

The custom consists in the fact that the pupils at monastic, collegiate and cathedral schools, in some places even the clergy themselves, elected an “abbot” or “bishop” who carried out a pompous festival and ceremonious processions.

During Advent in the Middle Ages there was a custom comparable to the boy bishop practice, that on certain days the servants and maids were in charge and played the role of the owners, while the latter took on the role of the maids and servants. On this occasion, a spicy flat cake, the gingerbread, was baked and distributed. Also the poor received it as a gift.

Christkindl

The Protestant Reformation in the 16th century suppressed saints, especially Nicholas. In Germany Martin Luther introduced the Christkindl (Christ Child) as gift-bringer who came at Christmas, emphasizing all good gifts coming from God. His followers later forbid Nicholas, allowing only Christkindl.

But in the Protestant countries, this change could not be implemented everywhere: The Netherlands and parts of Germany stuck to the old date of gifts and St. Nicholas. The custom in 16th century Germany, as described by Thomas Naogeorgus:

“Saint Nicholas money used to give.

To maidens secretly,

Who, that he still may use.

His wonted liberalitie.

The mothers all their children on the eve.

Do cause to fast.

And when they every one at night.

In senselesse sleepe are cast.

Both Apples, Nuttes, and peares they bring,

And other things besides.

As caps, and shooes and petticotes,

Which secretly they hide,

And in the morning found, they say.

That this Saint Nicholas brought.”

Around 1930, “the Christkind” had prevailed in north-west and south-west Germany, and in the other parts of the country “Santa Claus” as the bringer of gifts.

In the course of development, “the Christ Child” mutated into “Santa Claus”, who in turn took on some of the characteristics and the name of St. Nicholas. In North America, “Father Christmas” is called “Santa Claus”.

Alpine farmer’s rules for St Nicholas day:

| Regnet es an Nikolaus, wird der Winter streng, ein Graus. Trockener St. Nikolaus, milder Winter rund um’s Haus. | If it rains on St Nicholas. the winter will be severe. Dry St. Nicholas day, brings mild winter around the house. |

Medieval Saint plays

By the time of the 16th century Reformation Nicholas customs had moved beyond the church into popular culture. St. Nicholas had been a favorite subject of medieval saint plays, making the story of his generosity well-known. In that way the saint moved beyond story and image, as shown in church fresco and glass, into dramatic presentation. From there St. Nicholas moved into home and shop. For two centuries bakers and sweet-makers had been making his image in gingerbread and marzipan to supply home celebrations. Even statutes passed to forbid selling these cookie, cake and candle likenesses in Delft, Arnhem, Utrecht and Amsterdam could not stamp out such a beloved custom.

His popularity kept the good saint alive in many places despite the Reformation’s repression of saints.

Saint Nicholas, the gift giver, with his early December day being the primary gift-giving day, in Tyrol and beyond. Whether gifts are given on Nicholas feast or at Christmas, his example still inspires acts of charity and generosity.

St. Nicholas – Patron Saint

Saint Nicholas is said to be just about everyone’s saint. Nicholas has been chosen as the special protector or guardian of people, cities, churches, and even countries.

Patron of Russia; Lorraine von Rosenheim in Bavaria (Germany); Amsterdam; Canton and City of Friborg in Switzerland; Bari, Meran/ Merano and Lagonegro near Potenza, Kingdom of Naples and Sicily in Italy; Norway (with Saint Olaf); Alicante in Spain; Spetses in Greece and New York.

Second Patron of the Diocese of Lausanne-Geneva-Fribourg and the Diocese of Bari-Bitonto.

Patron of cattle, horses, and sheep in Poland.

for happy marriage and recovery of stolen items; Protection from wolves and wildbeasts; Lawsuits lost unjustly; Rheumatism; against water hazards, Thunderstorms, distress at sea; fire and thieves.

Patron Saint of:

Children, students, boys, girls, virgins, women who wish to have children, those giving birth and the elderly, the altar boys and the Sinti and Roma and Lemko people of Ukraine.

- Archers

- Apothecaries (pharmacists)

- Armed forces police

- Bakers

- Banker

- Bargemen

- Barrel makers

- Boatmen

- Bottlers

- Brewers

- Brides

- Businessmen

- Butchers

- Button-makers

- Candle makers

- Captives

- Chandlers (suppliers of ships)

- Children

- Choristers

- Citizens

- Clergy

- Clerks

- Cloth trade & merchants

- Coopers (barrelmakers)

- Corn measurers & merchants

- Court recorders, registrars, clerks

- Dock workers

- Drapers

- Druggists

- Embalmers

- Ferrymen

- Falsely accused

- Firefighters

- Fishermen

- Florists

- Grain dealers & merchants

- Grocers

- Grooms

- Haberdashers

- Infants

- Infertile

- Judges

- Lace makers & sellers

- Lawsuits lost unjustly

- Lawyers

- Linen merchants

- Longshoremen

- Lovers

- Mariners

- Merchants

- Military intelligence

- Millers

- Miners (in Russia)

- Murano glassmakers (in Venice, Italy)

- Murderers

- Navigators

- Newlyweds

- Notaries

- Oil merchants

- Orphans

- Packers

- Parish clerks

- Paupers (poor people)

- Pawnbrokers

- Peddlers

- Perfumeries and Perfumers

- Pharmacists

- Pilgrims

- Pirates

- Poets

- Preachers

- Prisoners

- Prostitutes

- Pupils

- Rag pickers

- Ribbon weavers

- Robbers & thieves

- Schoolchildren

- Sailors

- Scholars

- Sealers

- Seed merchants

- Shearmen

- Shipwreck victims

- Ships carpenters

- Shoemakers & Shoecleaners

- Shopkeepers

- Skippers

- Soldiers

- Spice-dealers

- Spinsters (A woman who spins; by extension, any person who spins; a spinner.)

- Students

- Tanners (One whose occupation is to tan hides)

- Teachers

- Timber merchants

- Travelers

- Unjustly condemned

- Unmarried men and women

- Watermen

- Weavers

- Wine porters, merchants & vendors

- Women, desirous of marrying

- Woodturners.

Advent tourism

Today the Nikolaus- and Krampus parades take place near the hugely popular Christkindlmarkt (Christmas market) in the center of villages and towns.

“Advent” (from the ecclesiastic term for the four Sundays before Christmas) and “tourism” may be words that don’t really go together in English, but in Tyrol the major Christmas markets are a huge tourist draw. There visitors enjoy an old tradition involving shopping, nibbling, and drinking one’s way through dozens, sometimes hundreds, of little stalls selling trinkets, foods, and mulled wine. Christmas is a big business — would St. Nicholas agree to all this consumerism?

Krampus are also an attraction in some markets. The Krampusruns are changing into modern shows, technology has been upgraded, music plays loudly, pyrotechnics, firecrackers and smoke play a big role. Some of the Krampus shows start mid-November with tourism season — a way to make money. Though some complain that the celebration is becoming too commercialized, many aspects of the old festival endure.

When it comes to Krampus future and related traditional folkloric festivities — if they are alive, they are modern customs.

Even when they’ve been around for 300 years.

Culture changes conform to the wishes and needs of the people.

Despite all the criticism, the scary and wild Krampus seems to have emanated more power of fascination than the good St. Nicholas, apart from the sacred context in the narrower sense — a fate that this custom shares with a number of other Christian festivals, for they are all subject to more or less strong secular and commercial transformations, that do not necessarily coincide with religious ideas and often help to popularize figures that were not originally the focus.

Krampus has evolved into a mass spectacle. The fact, that the evil and the uncanny simply seem more interesting and exciting to many than the good, is likely to play an important role in the popularity that Krampus has enjoyed to this day.

In addition, both religious and social principles are often based on the dichotomy of good and evil — the evil figure is indispensable for illustrating such systems. Krampus is also about the ritualization of aggression, which directs it into comparatively regulated channels and thus makes it more controllable.

In the late 20th century, and in recent years the appetite for large-scale “Krampus runs” (without St. Nicholas to tame them) has grown across the Alps and thousands and thousands of horned Krampus roam the mountains… Perhaps we should all be very good this Christmas, just in case Krampus comes wielding his birch sticks.

After all, the wild haunt could very well be watching you.

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- Boguslawski Alexander. The vitae of St. Nicholas and His Hagiographical Icons in Russia, Vol. 2. Doctoral dissertation University of Kansas. 1980.

- Ludwig von Hörmann. Tiroler Volksleben. 1909. (sagen.at)

- McDaniel Spencer. www.talesoftimesforgotten.com/is-krampus-really-pagan

- Michael the Archimandrite, Life of Saint Nicholas

- Rest. Seiser. The Krampus in Austria. Ethno Scripts. 2016.

- Schäfer Joachim. Ökumenisches Heiligenlexikon.

- Ridenour Al. The Krampus and the Old, Dark Christmas: Roots and Rebirth of the Folkloric Devil. 2016.

- Seal, Jeremy. Nicholas: The Epic Journey from Saint to Santa Claus, New York: Bloomsbury Publishers © 2005, pp. 152, 153.

- St Nicholas, the Gift Giver www.stnicholascenter.org/gift-giver St Nicholas Center Collection.

- The Real St. Nicholas, selections from The Life of Nicholas by Symeon the Metaphrast, ca

- https://christianityfaq.com/protestants-belief-about-saints/

- https://www.nikolospiel.at/

- www.berchtesgaden.de/buttnmandl-and-krampus

- www.britannica.com/Saint-Nicholas

- www.caidwiki.org/Saint_Nicholas_and_the_Christmas_Demons

- Krampus on Wikipedia

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_Nicholas

- www.etymonline.com/nicholas

- www.maskmuseum.org/austrian-perchten

- https://www.gasteinerperchten.com

- www.ool.co.uk/krampus-whos-that

- www.sagen.at

- www.heiligenlexikon.de/BiographienN/Nikolaus_von_Myra.htm

- www.sagen.at/vorweihnachtszeit

- www.sinterklaasmijnhobby.nl

- www.nikola-ygodnik.narod.ru/index.htm

- www.catholicvoice.org.au/scientists-reconstructed-the-face-of-st-nicholas-heres-what-they-found/

- www.stnicholascenter.org/demons-be-gone