BUON GIORNO – Mornings in Northern Italy are made of Cappuccino and cornetto, a croissant or brioche, at the local bar. Cappuccino consists of equal proportions of espresso, steamed milk, and frothed milk. Discover the Italian tradition of breakfast Cappuccino at the bar.

In this Article

The Italian breakfast

How we Italians consume the first meal of the day is peculiar. While in many places it’s customary to start the day with a rich, nutritious breakfast – soups, eggs, juice, rice, cereal, meet, cheese – the Italian breakfast features caffeine and sugary, yeasty carbs.

“Without my morning coffee I’m just like a dried up piece of roast goat.”

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) The Coffee Cantata

Frothed milk was at first, exclusively available at the bar, made with the steamer on coffee machines. Today there are several possibilities to make frothy milk for cappuccino at home. Nevertheless we love to visit a bar for coffee and sociability.

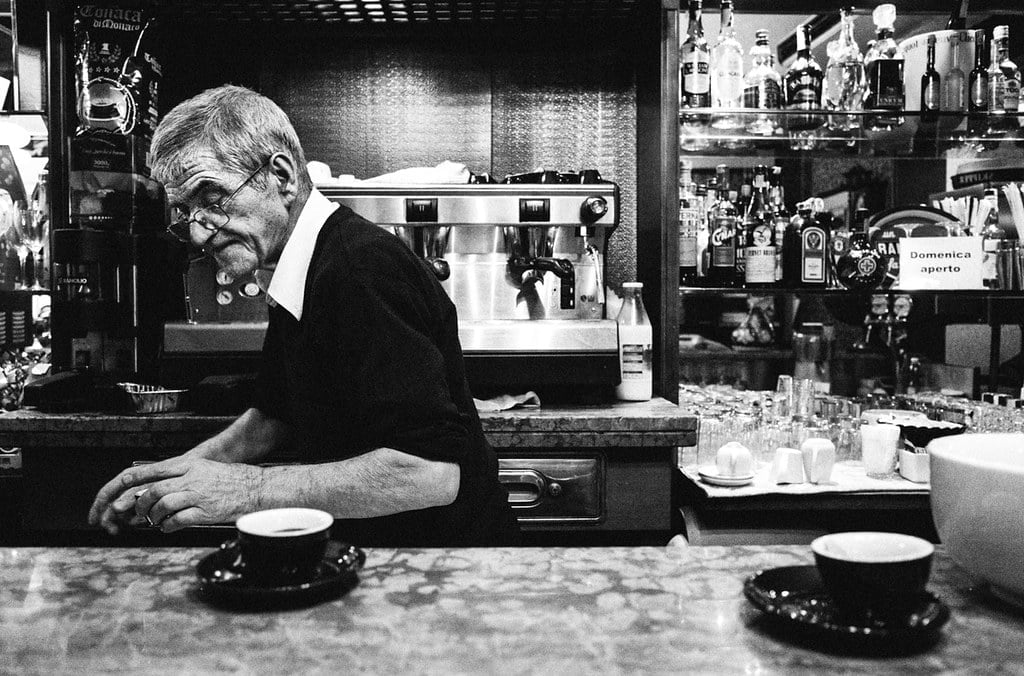

A symphony of breakfast music at the bar

Bar espresso machines have a valve with a long nozzle that is feed into the upper part of the tank where the steam gathers. When the valve is opened by unscrewing a knob, the compressed steam hisses out of the nozzle. The steam wand is wiped down with a damp rag and then turned on briefly until the water is flushed out, so to clean it.

Frothed milk

The barista pours cold milk into the stainless steaming pitcher, inserts the nozzle into the milk, and opens the valve – hissing and whistling – some gurgling noises, the compressed steam shoots through the milk, heating it and raising an attractive head of froth. As it swirls around and heats up the steam wand might whistle at a higher pitch until it is finally turned off. The pitcher is knocked onto the bar counter in order to break any small bubbles in the milk.

The white frothed milk is gently poured into the espresso – cappuccino is served.

And again, the sound of the grinder, the snap, snap, snap as the grounds fall from the grinder into the portafilter, the hissing of the steam wand and the filter holder slamming on the floorboards comprise a symphony of breakfast music.

Simultaneously, the aroma of coffee with the sweet fragrance of cornetti or brioche, as the barista greets you with a smile and a good morning – starts your day off by feeding body and soul.

“Buongiorno” because morning is the usual time of day to enjoy a cappuccino at the bar, and that can be a late morning also. After lunch or dinner cappuccino is unpopular, milk, we believe, sits heavily in the stomach and requires digestion:

cappuccio is a food rather than a beverage.

Further cappuccinos are a northerly preference and nearly absent from Rome downwards.

The value of coffee at breakfast

Pellegrino Artusi, the father of Italian domestic cuisine, tells us about the value of coffee at breakfast in his 1891 masterpiece, Scienza nella cucina e I’Arte di Mangiar Bene:

Upon awakening in the morning, find out what best agrees with your stomach. If it does not feel entirely empty, limit yourself to a cup of black coffee; and if you precede this with half a glass of water mixed with coffee, it will better help to rid you of any residues of an incomplete digestion.

If, then, you find yourself in perfect form and (taking care not to be deceived, for there is also such a thing as false hunger) you immediately feel the need for food – a definite sign of good health and presage of a long life – this is a most suitable moment, depending on your taste, to complement your black coffee with a piece of buttered toast, or to take some milk in your coffee, or to have a cup of hot chocolate.

Today, this translates into a habit of beginning the day with a black coffee brewed in a Moka or Napoletana, accompanied at most by dry biscuits, before perhaps taking a cappuccino and croissant an hour or two later in the bar either on the way to or during the first break from work.

We Italians eat a late dinner, sometimes very late in the evening, that might be a reason that we are not really hungry in the morning.

And there is also the merenda or la merendina we eat in Italy. “A little snack”, taken in the mornings betweeen breakfast and luch, or between lunch and dinner and that can be: bread with all kinds of cured meats such as mortadella or salami, cheese, tomatoes, a little fried treat, a slice of pizza, or sweet Nutella chocolate on bread. There’s sweet and savory pastry — or gelato, ice cream or fruits.

The word merenda, comes from the late Latin verb “merere” (deserve), and means “things you have to deserve”.

The conviviality of breakfast at the bar

Massimo Montanari, in Il riposo della polpetta e altre storie intorno al cibo, defines Italian breakfast at the bar:

Every culture has its own breakfast, and it’s not even said that it’s mandatory to have it: how many Italians are still satisfied with a coffee, and no one is surprised? The range of possibilities seems almost infinite: the tastes and choices of the individual, in this rite of passage from night to day, increase the unpredictability rate of the gesture.

It will be said that all food uses are the result of a culture and therefore vary over time and space, as well as in personal options. Breakfast is possible more. Because the very concept of “breakfast” is far from obvious. In the ancient world there doesn’t seem to exist a specific way to think of it, a name to indicate it. Among the daily meals it does not have a precise identity. There are no particular foods or drinks to qualify it; if anything, sometimes, methods of intake that define it ‘negatively’ with respect to the main meals: breakfast can be taken standing up instead of sitting or lying down; alone rather than in company.

Breakfast at the bar comes to mind, standing at the counter, not speaking, and a few threads of continuity can be glimpsed. Even if, to tell the truth, the same breakfast at the bar does not seem without its “convivial” dimension: especially for one person, coffee or a croissant are also a way to share the gesture with other diners, even if casual albeit silent.

The difficulty that doctors and dieticians still encounter today in making themselves heard when they recommend the importance of a “proper” breakfast, to respond in a balanced way to the caloric needs of the day, is in itself proof that it is not at all a question of a established practice. Nothing is obvious and taken for granted, in the life and culture of men.

Caffé al bar is a ritual – a way of life.

Eccentric, as coffee is a household essential drink and the Napoletana or Moka, is in constant use and placed in prime position in the kitchen. For us, home brewed coffee is still a treat – a wonderfully rich aroma circling the house – a much-needed fix of caffeine – a delightful breakfast call – Her hum opening the day, is so singularly pleasant that the writer Frances Yates called it

“the most beautiful music since Mozart”.

But after that it’s the grinding, banging, pounding, clanking, humming, gurgling, hissing and whistling of Italy’s bars, where the morning magic takes place.

On entering the bar, you are greeted with the usual

Ciao! Buon giorno

Come va? –

“Good morning, hello How are you?” both by barman and bar frequenting friends and acquaintances.

The familiarity has already satisfied a sense of comfort whether or not you chose to embark on a full-on conversation or just return with “Ciao”.

Without requesting, the barista that knows your palate, has already placed your coffee on the counter; a feat in itself to remember all those usuals but made simpler by the fact that for breakfast there are just a few options around espresso:

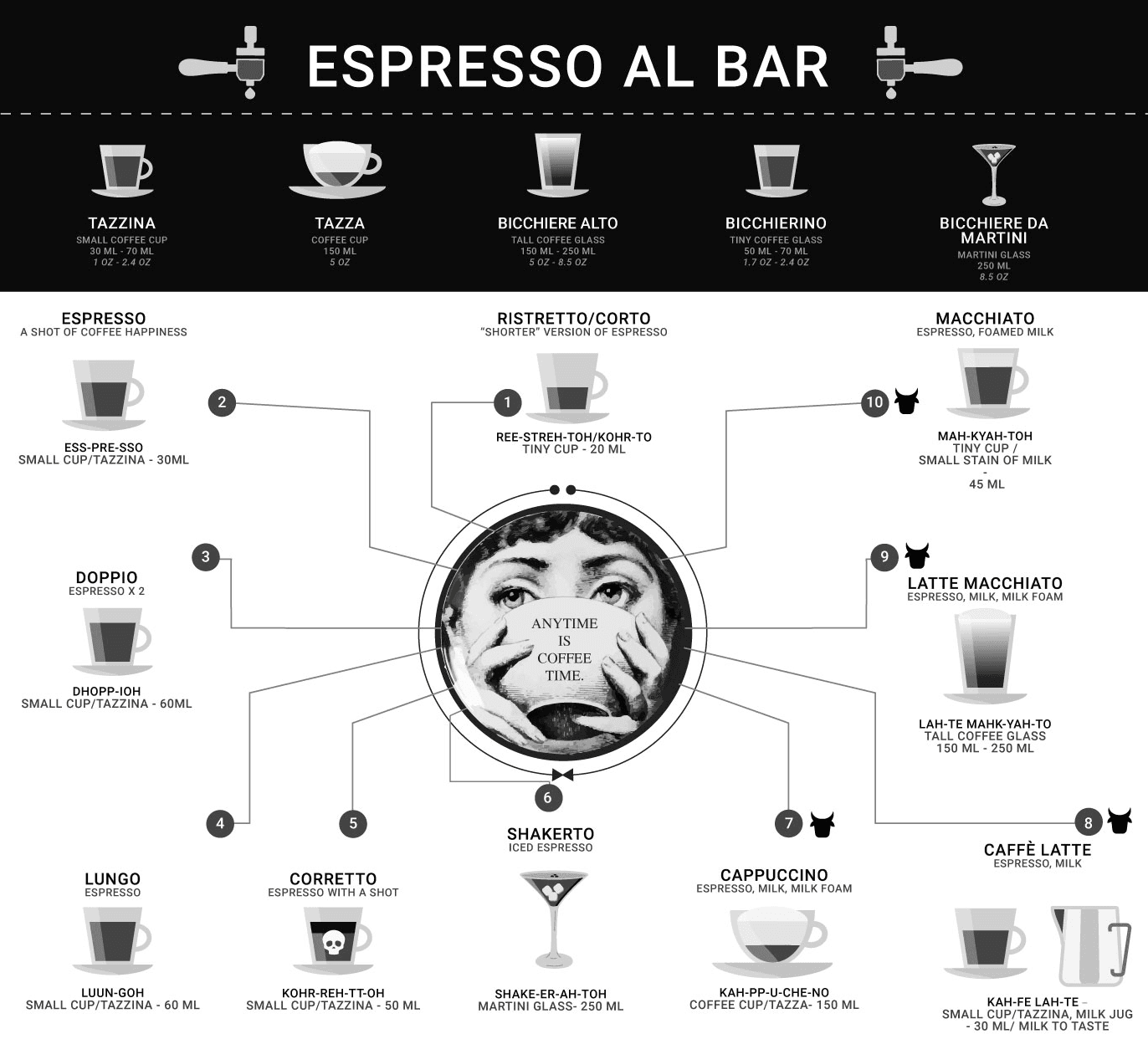

Menu: Caffè al BAR

- Ristretto ree-STREH-toh or corto Kohr-to – meaning a, “shorter” version of an espresso, using less water

- Caffè KHa-ff-Ee – a tiny shot of espresso – ESS-pre-SSo – with a unique Italian palate that comes down to not being over-watered or over-roasted. The espresso crema (the word has passed into English), fine and dense in texture and a hazelnut brown color, has to cover the surface of the espresso in the cup, a tazzaina ta-ZZ-II-na.

- Doppio DHOPP-ioh – meaning “double,” extracted using double the amount of ground coffee in a larger-sized portafilter basket

- Lungo LUUN-goh – meaning a “longer” version of an espresso, using more water, the espresso is filling the tiny cup nearly to the rim

- Caffè corretto – KohR-Reh-TT-oh – meaning “correct,” a shot of liquor is ether served with a shot of espresso or finds his way into the tiny cup [in the morning..sic!]

- Shakerato Shake-er-Ah-to – a fresh espresso mixed with sugar and ice until it froths as it’s poured into a chilled glass

- Cappuccino Kah-PP-u-CHE-no – frothy milk with a shot of espresso, 1/3 of coffee, 1/3 steamed milk and 1/3 of foam, served in a tazza ta-ZZ-a a cappuccino cup

- Caffè e latte KHa-ff-Ee e La-TT-e is an espresso, with steamed milk served separately in a small jug. International friends of ours told us, that ordering latte in Italy got them a glass of hot steamed milk – no coffee or coffee art for miles around.

- Latte macchiato Lah-TTe mahk-YAH-tho – steamed milk “stained” with espresso and an additional layer of frothed milk on top, served in a tall glass.

- Or the golden midway, il caffè Macchiato Mah-KYAH-toh – an espresso stained with foamed milk.

In the Italy of coffee, however, you just need to change city to find variations in color and aroma, taste and quantity in the cup.

…The Italians know that everything in their country is … imbued with their spirit. They know that there is no need, really, to distinguish or to choose between the smile on the face of a cameriere and Donatello’s San Giorgio… They are all works of art, the ‘great art of being happy’ and of making other people happy, an art which embraces and inspires all others in Italy, the only art worth learning, but which can never be really mastered, the art of inhabiting the earth.

Riccardo Pazzaglia (1926 – 2006) Italian actor, film director, screenwriter, songwriter, TV and radio personality.

The tradition of cornetto at the bar

Na tazzulella ‘e cafè (a cup of coffee), cornetto e cappuccino (croissant and cappuccino), macchiato con brioche (a macchiato and pastry): Italians and caffé, a traditional and shared culture we all live by.

On mornings, we drink espresso or cappuccino standing at the bar or sitting at the table, almost always accompanied by a sweet pastry, in all their regional glory.

Naples may have the sfogliatella while Rome has its maritozzo and Sicily claims the cannolo… but the cornetto remains the indisputable symbol of the Italian breakfast:

“vuoto” (empty) or “ripieno” (filled) with “crema” (pastry cream), “marmellata” (with marmalade), “miele” (honey, this is often made with an integrale, wholewheat, dough), “cioccolato” (chocolate) or con burro (butter) e Nutella.

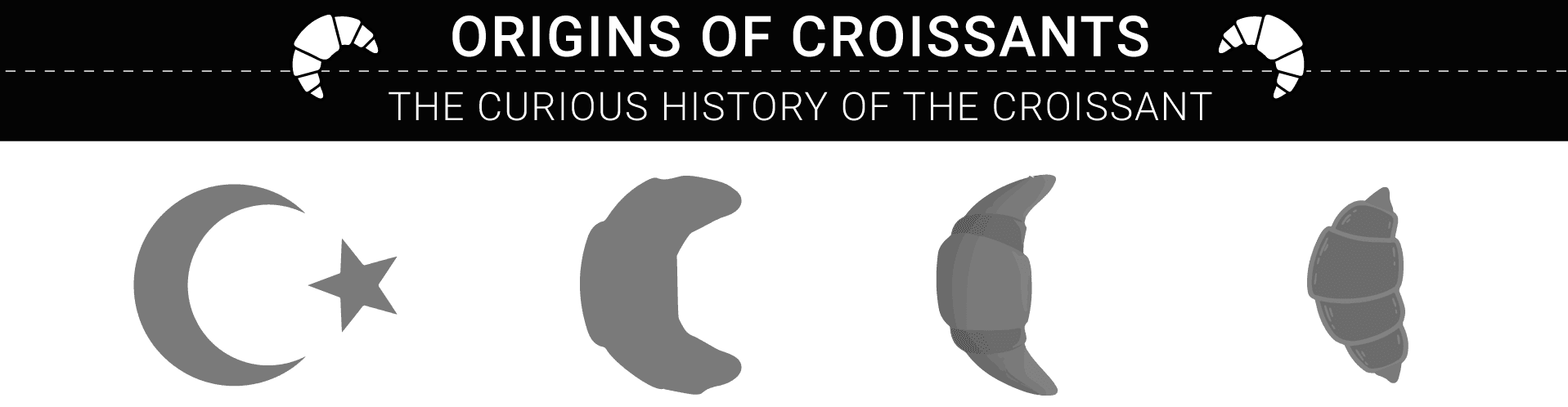

The curious history of the Pfizer (Kipferl) – croissant – cornetto

Lee Stewart Allen, refers this legend in his book, Devil’s Cup. A History of the World According to Coffee:

Back in 1683, during the Turkish siege of Vienna, a baker named Peter Wender heard a curious tick! tick! while working late at night in his basement bakery. It was the Turks digging their secret tunnels. He warned the city officials and later created a sweet bread roll shaped like the Turks’ crescent moon to advertise his contribution to the war effort.

A similar story is also told across Hungary, but with Budapest as the setting, not Vienna.

Using bread as political propaganda was quite common back then; when King Gustav Adolf II of Sweden ravaged Germany only fifty years earlier, every gingerbread in the area was soon decorated with Adolf’s face transformed into a child-eating monster.

After the Turks were defeated, it became the Viennese custom to serve Wender’s little crescent roll, called the Pfizer, with morning coffee. And there it would have ended except that a century later a seventeen-year-old Viennese princess named Marie Antoinette moved to Paris to marry Louis XVI, king of France. Homesick, she insisted that the French bakers learn to make pfizer for her breakfast using yeast dough (Brioche). The bakers added butter and yeast, and since it would have been unthinkable for a queen of France to eat anything but “French” pastry, they renamed it le croissant de lune, which means crescent moon in French.

A croissant, a crescent-shaped French pastry made from laminated, yeast-leavened dough and butter. CC A-S A 3.0 U

Another story attributes the Kipferl the Austrian official August Zang, founder of the Boulangerie Viennoise (Viennese Pastry Shop) in Paris around 1839, whose specialty was Kipferl along with other Austrian pastries. Its typical crescent shape soon changed the name into what we still know today as croissant.

The relations between Austria and Italy in 1683 were so intense that in a few years the crescent bun crossed over into North Italy. The Italian croissant recipe today differs from the croissant due to the presence of egg in the dough and a greater quantity of both butter and sugar.

Another account, tells how the cornetto came to South Italy. In 1768 Maria Carolina of Habsburg married Ferdinand IV of Bourbon and was crowned Maria Carolina, Regina (queen) di Napoli e Sicilia. Along with coffee, Maria Carolina brought the Kipferl (cornetto) to Naples: the successful coffee-cornetto pairing was recommended to her by her sister Maria Antonietta of France.

HISTORY – LEGEND: Kapuziner – Cappuccino – Cappuccio

Cappuccino – St. Francis of Assisi and the Capuchin order in Italy

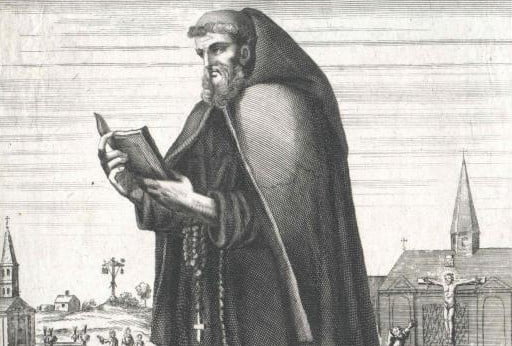

Lee Stewart Allen collected this story in his work, “Devil’s Cup. A History of the World According to Coffee“:

The story of how the Capuchin order became associated with the drink begins in the Italian village of Assisi. It was here, around 1201, that a fellow named Giovanni began to act a little odd. He wandered about naked. He talked to birds. If it had happened today, he would have been institutionalized. But it was the medieval period, so he was canonized. We know him today as St. Francis of Assisi.

A religious order immediately sprang up around his teachings and just as quickly splintered into a dozen factions. Then came Matteo da Bascio (Matteo Serafini). He was a quiet Franciscan monk who loved St. Francis and his poverty and his birds and his simplicity. One day the ghost of St. Francis visited him to complain about his order’s decadent behavior. What grabbed Matteo’s attention, however, was the saint’s outfit – he was wearing a pointed hood, not the square one mandated by the order. Outraged, Matteo petitioned the Vatican for the right to wear a peaked hood. The pope acquiesced.

The other Franciscans, however, were furious with his new holier-than-thou habit and threw Matteo into a dungeon. Matteo refused to give up his new pointed hood, in addition, he grew a beard and traveled barefoot. The Franciscans, in turn, refused to let him go. It grew so ridiculous that the pope intervened and created a completely new order just for Matteo, thus liberating him from Franciscan authority.

And so was born the new Order of Friars Minor Capuchins, the principal branch of the Franciscans.

The hood of the Capuchin order, cappuccio in Italian, is a reference to the pointed hood Matteo was fond of and, later, to the “cap” of whipped cream or steamed milk (perhaps we should call it a halo?) that crowns the cappuccino.

Lee Stewart Allen

It was, however, the choice of red-brown as the order’s vestment color that, as early as the 17th century, saw “capuchin” used also as a term for a specific color. While Francis of Assisi used uncolored and un-bleached wool for his robes, the Capuchins colored their vestments to differ from Augustinians, Benedictines, Franciscans, and other orders.

There is a 1625 etching from Cairo showing what appears to be milk and coffee combined. Also the Dutch ambassador to China experimented with milk in his coffee in 1660, this innovation did not become widely accepted, so Ukers in his All About Coffee. from 1928.

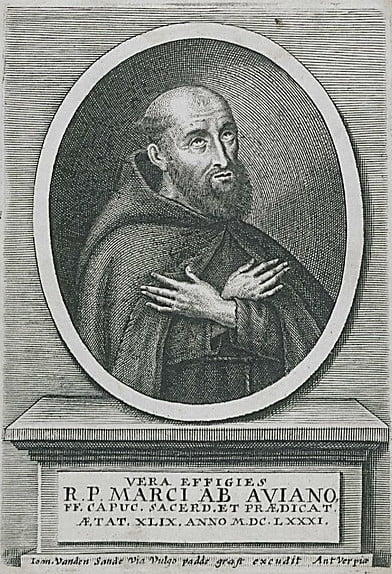

Kapuziner – Marco da Aviano in Vienna

Alessandro Marzo Magno, historian, journalist and author of the book Il genio del gusto – Come il mangiare italiano ha conquistato il mondo, The Italian genius – How Italian food conquered the world, published this legend:

It seems that the term Kapuziner takes its name from the friar of the Capuchin order Marco da Aviano, sent in 1683 by the Pope to Vienna with the aim of convincing the European powers to form a military coalition against the Turks who were besieging the city.

Recognized as the savior of Europe from the Muslim danger, beatified in 2006, he seems to have invented the cappuccino: during his stay in the city the religious man is said to have entered a Kaffeehaus, but unable to drink the strong beverage, asked for something to sweeten it.

“Kapuziner!” exclaimed a waiter seeing the strange concoction of milk (some say cream) drunk by the friar. The rest is history, or rather legend.

The dark brown robe is reminiscent of coffee, and the cream is as white as their belt.

Vienna’s kapuziner, however, has no cap and was supposedly created when a local member of this order added milk to his coffee.

Kapuziner – Franz Georg Kolschitzky in Vienna

During the Turkish-Prussian war, Vienna was invaded by the Turkish army, legend has it, that they left bags of coffee behind when they left the city. Franz Georg Kolschitzky also called Jerzy Franciszek Kulczycki recognized the value of the coffee beans and opened a coffee house in 1683 or 1684.

His shop with the sign “Zur blauen Flasche” (“To the blue bottle”), was equipped with rough tables and long benches and in 1697 the filtered coffee was served in big cups accompanied by large wooden spoons. Since

“the color of the drink was as repugnant to the sight of his fellow citizens as its acrid taste was repugnant to their palates”

Historian, Gérard-Georges Lemaire, I Caffè letterari, 1988.

Kolschitzky had the idea of adding cream and honey to sweeten it. This is, legendary, how Viennese Kapuziner was born.

Legend has it, that later a baker, wishing to commemorate the defeat of the Turks, made crescent-shaped sweeets, the Pfizer or Kipferl, and Kolschitzky offered them to his customers greedy for delicacies.

Since, Kaffee was accompanied by Kipferl – croissants and other sweet delights.

Cappuccino entered Italian language in 1848

The Wiener Kapuziner

Jonathan Morris, professor of modern European history at the University of Hertfordshire and leading coffee historian in England writes:

“It seems probable that the term cappuccino entered the Italian language during the period of Austrian domination over much of Northern Italy, as a derivative of the Austrian Kapuziner.”

The coffee bore little resemblance to the beverage we know today. An Englishman caught up in the Viennese popular insurrection of 1848 recorded how:

“The coffee-house was my only resource: there was at least some comfort in sipping a kapuziner.

This word means in English a Cappuchin monk, but it signifies in Austrian parlance a glass of coffee with milk.”

[today it is cream: Sahne or Schlagobers]

“The Austrians take their coffee in glasses, like the Russians, but they do not sweeten it with honey as that civilized nation are wont to do.“

Today the Kapuziner or Capuchin is typically a double espresso with a serving of whipped cream on top – this creates the color of the habit of the capuchin friars. It is the namesake for the cappuccino.

Professor Leopold Edelbauer, the “coffee pope” of Vienna sees developments a little differently. In his opinion, Italian travelers once brought Kapuziner coffee with them to their homeland. The cappuccino was then prepared with milk foam – for the professor an “imitation” of the Austrian original. They probably used milk because whipped cream doesn’t keep well in hot Italy.

The Franziskaner friars, the name also for another coffee preparation in Austria. The Franziskaner is a single espresso con panna, there is Schlagobers, whipped cream on top of the espresso.

Travel guides to Austria in the early 1900s confirm that Capuziner or Kapuziner was a beverage “with more coffee than milk” in contrast to melange for which the reverse was true.

Is the Wiener Melange a Cappuccino ancestor?

The melange, today is still served in Viennese coffee houses. The name is derived from the French (melanger = to mix) and that says the most important thing: It is a 1:1 mixture of a small espresso (usually mild varieties) and hot milk. Milk foam is then added on top, but never whipped Schlagobers (or cream)! The melange is served in a larger cup; a glass is inappropriate.

Anecdotally, I’ve also seen menus where the Melange is based on a single espresso and the cappuccino on a double espresso. And menus where the reverse was true. What diversity there is. Depending on the place a Viennese Melange can be a Cappuccino.

Baedeker’s 1904 guide provides an introduction to the coffee menu and caffé culture in Italy, the term cappuccino was already in use by then:

“Cafès are frequented mostly in the late afternoon and evening. The tobacco-smoke is frequently objectionable.

Caffè nero [black], or coffee without milk, is usually drunk.

Caffè latte (served only in the morning) is coffee mixed with milk; cappuccino, or small cup, cheaper; or caffè e latte i.e. with the milk served separately, may be preferred.“

Both cappuccino and caffè latte were combinations of coffee and milk that could as easily be prepared at home as in the cafè, while the difference between the two was the relative proportions of coffee and milk in the cup.

In the first edition of his dictionary of new words in Italian in 1905, Alfredo Panzini confirms that the smaller quantity of milk in the cappuccino spawned its name. He defined cappuccino as

“Black coffee ‘corrected’ with milk. A colloquial term probably derived from the similar color to the habit of the capuchin friars.”

Panzini suggested that the word cappuccino had a regional origin, linking it to northern Italy during the period of Austrian rule that lasted until the 1860s, and in the case of Trieste, the Habsburgs’ principal port on the Adriatic, to 1918.

There is little demand for cappuccino in those southern regions of Italy that never came under Austrian control, while a cappuccino in Trieste is served much shorter than elsewhere, usually in an espresso cup, perhaps reflecting its likely original serving style in a demitasse.

Jonathan Morris, analyzing subsequent editions of Panzini’s dictionary, finds, that the use of “cappuccino” in relation to coffee preceded that of “espresso.”

In the 1918 edition, for example, cappuccino is defined as above, but “espresso” is only mentioned to denote fast trains and postal deliveries, perhaps because the first espresso machines claimed to make “instantaneous” coffee. Even in 1931, when Panzini stated that it was commonplace to use “espresso” to describe a coffee made “using a pressure machine or a filter,” the fact that he links both forms of preparation placed the emphasis on express service rather than on the coffee itself. His definition of cappuccino remained essentially unchanged:

“Cappuccino. Black coffee mixed with a little milk. Everyday usage, derived probably from the similar colour to the habit of the Cappuccin friars.”

Cappuccio

Jonathan Morris further tells us, that:

“The timing, along with the absence of any reference to the milk having been heated, yet alone steamed, in the definition, suggests that cappuccino was at this stage used as a term for a simple domestic beverage. That appears to have changed by the latter 1930s as a drinking out culture based around espresso took hold.“

By 1938 a slang term cappuccio was already being used in Italy “somewhat jokingly instead of cappuccino, almost as if to recommend to the barista not to give one too little, (-ino is an Italian suffix meaning rather small).

Cappuccino comes from Latin Caputium, later borrowed in German / Austrian and modified into Kapuziner.

It is the diminutive form of cappuccio in Italian, meaning “hood” or something that covers the head, thus cappuccino literally means “small capuchin”.

This color is quite distinctive, and capuchin was a common description of the color of red-brown in 17th century Europe.

Certified Italian Cappuccino

The Italian Espresso National Institute (INEI) a private institution, founded by Italian companies active within the coffee industry, devised parameters for certified Italian cappuccino that were approved by the Italian parliament in 2007.

The guidelines are 100 ml of cold milk expanded to a volume of 125 ml by foaming to a temperature of around 55°C and poured over a certified Italian espresso of 25 ml in a 150–160 ml cup.

The overall proportions of the beverage and the relatively low temperature of the milk, meaning that the cappuccino can be drunk straight away.

The evolution in espresso preparation in the 50ies and sixties changed the nature of cappuccino in Italy, given the new taste profile at the base of the beverage. Today, however, from a sensory standpoint, Certified Italian Cappuccino is of a white colour, trimmed with a brown edge of various thickness in the classical cappuccino, with decorations ranging from brown to hazelnut in the decorated cappuccino. The cream has a tight mesh with very fine or absent eye formation. INEI describes it further as:

“The Certified Italian Cappuccino has an intense aroma combining the underlying scents of flowers and fruits with the bolder scents of milk, of toasted (cereals, caramel), chocolate (cocoa, vanilla) and dried fruits…”

It discloses its remarkable body through an inviting sensation of cream and of high spherical perception, supported by a mild bitter taste and by a balanced, almost imperceptible acidity. Astringency is practically absent.

Latte macchiato and Caffè latte

Diluting espresso with milk, softens the taste and the kick, we Italians love the fast caffeine shot.

Into the 1980s, a sense persisted that drinking cappuccino was somewhat feminine, and to this day the latte macchiato (prepared by dropping an espresso shot into a glass of steamed milk) remains a rare sight in the Italian bar – ordered only by children, convalescents, and those (usually ladies of a certain age) with fragile stomachs.

Caffè latte is mostly a domestic drink brewed with the Moka pot or Napoletana adding milk to the cup. My grandmother would drink it in the morning, often dipping it with biscuits, homemade cake or bread.

Caffè e latte, coffee and milk, at the bar, is usually an espresso, with steamed milk served separately in a small jug.

International friends of ours told us, that ordering a LATTE in Italy got them a glass of hot steamed milk – no coffee or coffee art for miles around.

We love a cappuccino and apparently it loves us back. PoYang_博仰/flickr CCA-SA 2.0 G

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

The history of coffee is an extraordinary study. If you would like to learn more about it, I heartily recommend the book, All About Coffee, by William Ukers. Written in 1928, it will delight you with detail.

- Lemaire Gérard-Georges. I Caffè letterari. 1988.

- it.wikiquote.org (https://it.m.wikiquote.org/wiki/Voci_e_gridi_di_venditori_napoletani)

Voci e gridi di venditori napoletani - http://90905.homepagemodules.de/t155f59-Cappuccino-Kapuziner-Melange-oder-wie-jetzt.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caff%C3%A8_sospeso

- Allegra World Coffee Portal www.worldcoffeeportal.com

- Artusi Pellegrino. Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well, transl. Murtha Baca and Stephen Sartarelli. 2003.

- Biderman Bob. A people’s history of coffee and cafés. 2013.

- Café Culture Magazine www.cafeculturemagazine.co.uk

- Carosello Bialetti: la caffettiera diventa mito https://www.famigliacristiana.it/video/carosello-bialetti-moka-mito.aspx

- Cociancich Maurizio. Storia dell’ espresso nell’Italia e nel mondo. 100% Espresso Italiano. 2008.

- Coffee Connaisseur www.coffeeconnaisseur.com

- Coffee Geek www.coffeegeek.com

- Coffee Origins’ Encyclopedia www.supremo.be

- Coffee Research www.coffeeresearch.org

- Coffee Review www.coffeereview.com

- Coffee Sage www.coffeesage.com

- Coffeed.comwww.coffeed.com

- Comunicaffe International www.comunicaffe.com

- Davids Kenneth. Espresso Ultimate Coffee. 2001.

- De Crescenzo Luciano. Caffè sospeso. Saggezza quotidiana in piccoli sorsi. 2010.

- De Crescenzo. Luciano. Il caffè sospeso.

- Eco Umberto. “La Cuccuma maledetta” in Agostino Narizzano, Caffè: Altre cose semplici. 1989.

- Global Coffee Report www.gcrmag.com

- Gusman Alessandro. Antropologia dell’olfatto. 2004.

- Hippolyte Taine, wrote in, Italy: Florence and Venice, trans J. Durand. 1869.

- https://www.italienaren.org/tradizioni-italiane-caffe-in-ginocchio/

- http://www.archiviograficaitaliana.com/project/322/illycaff

- http://www.baristo.university/userfiles/PDF/INEI-M60-ENG-Public-Regulation-EICH-v4-1.pdf

- http://www.coffeetasters.org/newsletter/en/index.php/category/a-baristas-life/

- http://www.coffeetasters.org/newsletter/it/index.php/il-galateo-del-caffe/01524/

- http://www.culturaacolori.it/fascismo-contro-le-parole-straniere/

- http://www.espressoitaliano.org/en/The-Certified-Italian-Espresso.html

- http://www.inei.coffee/en/Welcome.html

- https://archiviostorico.fondazionefiera.it/entita/585-bialetti-industrie

- https://bialettistory.com/

- https://cdn.intechopen.com/pdfs/55623.pdf Severini Carla. Derossi Antonio. Ricci Ilde. Fiore Anna Giuseppina. Caporizzi Rossella. How Much Caffeine in Coffee Cup? Effects of Processing Operations, Extraction Methods and Variables

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drip_coffee#Cafeti%C3%A8re_du_Belloy

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ISSpresso

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Italian_meal_structure

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neapolitan_flip_coffee_pot

- https://hal.science/hal-00618977/document

- https://hub.jhu.edu/magazine/2023/spring/jonathan-morris-coffee-expert/

- https://ineedcoffee.com/the-story-of-the-bialetti-moka-express/

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caff%C3%A8

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caff%C3%A8#Risvolti_etici_e_sociali

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napoletana

- https://italofonia.info/la-politica-linguistica-del-fascismo-e-la-guerra-ai-barbarismi/

- https://italysegreta.com/italian-hospitality-the-invite/

- https://library.ucdavis.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/LangPrize-2017-ElizabethChan-Project.pdf

- https://memoriediangelina.com/2009/08/11/italian-food-culture-a-primer/

- https://mostre.cab.unipd.it/marsili/en/130/the-everyday-eighteenth-century

- https://napoliparlando.altervista.org/cuccumella-la-caffettiera-napoletana/

- https://specialcoffeeitaly.com/barista-espresso-coffee-machine/

- https://specialcoffeeitaly.com/italian-breakfast-cappuccino-cornetto/?_gl=1*1gjfoya*_ga*OTE0MDM2ODM5LjE2OTMzNjE5OTg.*_ga_2HTE5ZB0JS*MTY5MzM2MTk5Ny4xLjEuMTY5MzM2Mjk0NS4wLjAuMA../

- https://specialcoffeeitaly.com/what-came-first-the-italian-bar-or-coffee/

- https://themokasound.com/

- https://uwyoextension.org/uwnutrition/newsletters/understanding-different-coffee-roasts/

- https://www.adir.unifi.it/rivista/1999/lenzi/cap2.htm

- https://www.bialetti.co.nz/blogs/making-great-coffee/using-bialetti-coffee-makers

- https://www.bialetti.com/ee_au/our-history?___store=ee_au&___from_store=ee_en

- https://www.bialetti.com/it_en/inspiration/post/ground-coffee-for-moka-should-never-be-pressed

- https://www.brepolsonline.net/doi/pdf/10.1484/J.FOOD.1.102222

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/Amsterdam/2014.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/Amsterdam/2014.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/Milan/2013/Gallery/Other/Amalia-Chieco

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/NewYork/2016.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/NewYork/2017.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/NewYork/2018.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/NewYork/2019.aspx

- https://www.coffeeresearch.org/science/aromamain.htm

- https://www.coffeereview.com/coffee-reference/from-crop-to-cup/serving/milk-and-sugar/

- https://www.comitcaf.it/

- https://www.ecf-coffee.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/European-Coffee-Report-2022-2023.pdf

- https://www.espressoitalianotradizionale.it/

- https://www.euronews.com/culture/2022/02/15/the-italian-espresso-makes-a-bid-for-unesco-immortality

- https://www.faema.com/int-en/product/E61/A1352IILI999A/e61-legend

- https://www.finestresullarte.info/en/works-and-artists/the-bialetti-moka-the-ultimate-romantic-design-object

- https://www.finestresullarte.info/opere-e-artisti/moka-bialetti-oggetto-design-ultimi-romantici

- https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/leisure/food/2022/02/15/italy-woos-unesco-with-magic-coffee-ritual/

- https://www.gaggia.com/legacy/

- https://www.gamberorossointernational.com/news/coffee-10-false-myths-to-dispel-on-the-beverage-most-loved-by-italians/

- https://www.gcrmag.com/calls-to-review-price-structure-of-italian-espresso/

- https://www.granaidellamemoria.it/index.php/it/archivi/caffe-espresso-italiano-tradizionale

- https://www.illy.com/en-us/coffee/coffee-preparation/how-to-make-moka-coffee

- https://www.illy.com/en-us/coffee/coffee-preparation/how-to-use-neapolitan-coffee-maker

- https://www.ilpost.it/2011/06/08/itabolario-bar-1897/

- https://www.itstuscany.com/en/bar-where-the-word-comes-from/“Cafe Hawelka”, John A. Irvin

- https://www.lastampa.it/verbano-cusio-ossola/2016/02/17/news/le-ceneri-di-renato-bialetti-nella-sua-moka-con-i-baffi-1.36565348/

- https://www.lavazza.com/en/coffee-secrets/neapolitan-coffee-maker

- https://www.lavazzausa.com/en/recipes-and-coffee-hacks/making-espresso-at-home

- https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/third-wave-coffee-meets-tradition-neapolitan-maker-bruno-lopez

- https://www.mumac.it/we-love-coffee-en/be-our-guest-en/progettazione-e-rito/?lang=en

- https://www.quartacaffe.com/images/pdf/carta-dei-valori.pdf

- https://www.repubblica.it/il-gusto/2021/07/26/news/caffe_il_piu_clamoroso_equivoco_gastronomico_d_italia-311835974/

- https://www.taccuinigastrosofici.it/ita/news/contemporanea/semiotica-alimentare/print/Pop-cibo-di-sostanza-e-circostanza.html

- https://www.thehistoryoflondon.co.uk/coffee-houses/

- https://www.wien.gv.at/english/culture-history/viennese-coffee-culture.html

- Illy Andrea. Viani Rinantonio. Furio Suggi Liverani. Espresso Coffee. The Science of Quality. 2005.

- International Coffee Organization www.ico.org

- Kerr Gordon. A Short History of Coffee. 2021.

- La cremina per il caffè: come farla bene. https://www.lacucinaitaliana.it/news/cucina/come-fare-la-cremina-del-caffe/

- Allen Lee Stewart. Devil’s Cup. A History of the World According to Coffee. 1999.

- Leonetto Cappiello – Wikipedia page on the creator of the 1922 poster La Victoria Aduino.

- Markman Ellis. The Coffee House. A Cultural History. 2005.

- Mennell Stephen. All Manners of Food. Eating and Taste in England and France. 1996.

- Montanari Massimo. Il riposo della polpetta e altre storie intorno al cibo. 2011.

- Montanari Massimo. Il sugo della storia. 2018.

- Morris Jonathan. A Short History of Espresso in Italy and the World. Storia dell’espresso nell’Italia e nel mondo. In M. Cociancich. 100% Espresso Italiano. 2008.

- Morris Jonathan. Coffee: A Global History. 2019.

- Morris Jonathan. Making Italian Espresso, Making Espresso Italian.

- National Coffee Association www.ncausa.org

- Pazzaglia Riccardo. Odore di Caffe’. 1999.

- Pendergrast Mark. Uncommon Grounds. The History of Coffee and How It Transformed Our World. 2019.

- Perfect Daily Grind www.perfectdailygrind.com

- Scaffidi Abbate Mario. I gloriosi Caffè storici d’Italia. Fra storia, politica, arte, letteratura, costume, patriottismo e libertà. 2014.

- Schnapp Jeffrey. The Romance of Caffeine and Aluminum. Critical Inquiry. 2001.

- Sibal Vatika. Food: Identity of culture and religion. 2018.

- Specialty Coffee Association www.sca.coffee

- Spieler Marlena. A Taste of Naples. 2018.

- Tea and Coffee Trade Journal www.teaandcoffee.net

- The Long History of the Espresso Machine. www.smithsonianmag.com

- The Pleasures and Pains of Coffee by Honore de Balzac

- The relaxation ritual https://themokasound.com/

- Tucker, Catherine M. Coffee Culture: Local Experiences, Global Commensality, Society and Cuture 2011.

- Virtual Coffee www.virtualcoffee.com

- World Coffee Research www.worldcoffeeresearch.org