Throughout Argentina, we notice roadside shrines amid of water bottles and a statuette of a lactating mother. Discover the folk saint Difunta Correa or Decreased Correa.

As you drive through Argentina (and to a lesser extent Chile and Uruguay) you will notice numerous roadside shrines. Those decorated with red flags are dedicated to Gauchito Gil, those surrounded by bottles of water are intended for Difunta Correa, or as she would be known in English The Deceased Correa.

In this Article

In Mendoza we met Graciella and her husband, Alberto, together we decided for a road trip to the Unesco world heritage sites of Talampaya, famous for it’s petroglyphs; and Ischigualasto, the prehistoric Valley of the Moon: with it’s curious rock formations and dinosaur fossils.

On the way back, in the middle of a desert of sand and stone, next to National Route No. 20, Alberto would say:

”We need to stop and take all the water bottles we have in the car with us!”

As we arrived at Vallecito, a hamlet in the Province of San Juan, we passed an altar of piled-up old cars… After this strange sight, we have been blinded by smoke coming from crucified sheep (asado “a la cruz“) being BBQ-ed on dozens of asado’s. Lots of merchants make a living at the sanctuary here, selling everything from beer to steaks to a wide assortment of trinkets.

Souvenirs, like statuettes in her classic posture (lying down, facing the sky with the child on one of her breasts, in the middle of an arid landscape), stamps, medals, red ribbons with the phrase “Difunta Correa protect …” and then “my home” or “my family”, “my work”, “my health” including car, and motorcycle brands. These ribbons, which are usually hung from mirrors, are blessed along with the car in question by a priest in the Capilla del Carmen in Vallecito.

This is also a place for families to barbecue and enjoy time together on weekends. Most people carry large bottles of water, a gift, that is sacred in the desert…We’re in the middle of nowhere but, according to legend, it is in fact the sanctuary of an Argentinean folk saint: Difunta Correa or Decreased Correa.

LEGEND: Difunta Correa

Deolinda Correa was born in La Majadita, in San Juan province, in the early years of the nineteenth century. She was married to Baudilio Bustos in her early twenties and the couple had a son. Around 1841, Bustos was conscripted into the troops of Facundo Quiroga, despite his resistance due to illness, perhaps pneumonia. Some say instead that Bustos was imprisoned by enemy forces, and taken away in chains toward La Rioja.

Deolinda could not bear the thought that her husband, sick or captive, was suffering without her care. She entered the desert with her infant son in her arms, following behind the troops on foot. The trail was soon lost, however, and Deolinda wandered under the merciless sun. She eventually ran out of water, collapsed in exhaustion, and died of thirst and exposure. Some livestock drivers found her shortly after and buried her body at the site, in Vallecito.

Her son survived by nursing at the breast of his dead mother.

Not one legend but many more

There is no single version of the story of the Difunta Correa. When Susana Chertudi and Sara Josefina Newbery published the first anthropological study in 1978 in the “Cuadernos of the National Institute of Anthropology”, under the title “Difunta Correa“.

They have found 28 different versions of the legend, and as many of her first miracles. In other stories Deolinda, or Dalinda, or Mercedes, went with two children, or went after her eldest son, and was even killed by a hailstorm.

This is a summary of the versions on the Deceased collected by the Anthropologists, drawn from earlier writings and from the oral tradition, which includes unpublished versions at the time of publication:

Time in which she lived: between 1820 and 1860.

Place where she lived: San Juan (most versions), La Rioja, Costa de Bermejo.

Names: Deolinda, Mercedes, Dalinda Antonia, Belinda.

Parents: Don Pedro Correa and Damiana; José Amador Correa and Rosario del Tránsito Ramajo.

Husband: Clemente Bustos, Baudilio Bustos, a young man from San Juan.

Qualities of the Difunta Correa: virtuous woman, beautiful woman.

Reasons why she leaves her home: to follow the husband, to follow the son; take a trip; looks for a village to live in until the return of her husband; search for her murdered husband; due to a drought, she flees from La Rioja to San Juan.

Route followed: road between San Juan to La Rioja; from San Luis to San Juan.

How she traveled: on foot; she goes on a ride. She carries a son in her arms.

Events on the road: she goes astray, she does not find water, her strength is exhausted; gives birth to a child; a storm; Sickness.

Death: of thirst (exhaustion and hardship); protecting her children from a hailstorm; of a disease.

Place of death: Vallecito; when crossing the desert; on top of a hill; in a desert called Camperito; in a place called Las Peñas.

Who find her: some muleteers, some travelers.

Her first miracle: already dead, her breasts continued to feed her son.

Burial: in the same place where she was found, on the plain, at the foot of a carob tree.

The burial: they place a cross on the tomb, cover it with stones.

Fate of the son (children): he survived; he died with her.

Miracles: discovery of the animals lost by Flavio Zeballos; others by a muleteer; protection from a storm; healing of sores; appearance as a guide for lost travelers.

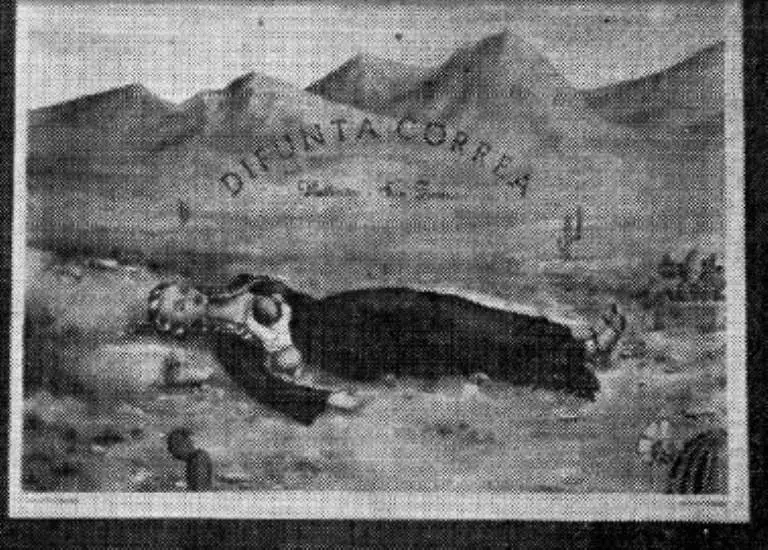

ICONOGRAPHY: Difunta Correa

All over Argentina, her small shrines can be found along roadsides. They are often ramshackle, little more than a crate containing a statue and with piles of plastic water bottles in front and sometimes old tires or car parts. At the center of many of these shrines the statue of a woman lying, facing the sky, an breastfeeding her child. The woman wears a red dress and sandals, has dark, long hair; She is beautiful and she is … dead.

Iconography, too, can be ambiguous. The image of Difunta Correa, that is now unrivaled, is possibly based on the foreground of the painting Fiebre amarillo en Buenos Aires (Yellow Fever in Buenos Aires). The original painting is by José Manuel Blanes; a copy by Ignacio Cavicchia was donated in 1949 to the Sarmiento museum in San Juan. The child in the painting holds the breast of the dead mother but is not actually breast-feeding.

The same is true of the image printed on the back cover of each issue of the magazine Difunta Correa: the infant is at the breast but not nursing, despite text to the contrary. The large statues of Difunta Correa at the shrine today and the countless replicas that are sold in the shops conform to the miraculous version: they all clearly depict the child nursing at the dead mother’s breast. The dead mother and living son of the yellow-fever painting represent the despair of an orphan.

Difunta Correas miracles

The breast-feeding miracle

Difunta Correa’s miraculous breast is unquestionably her most important attribute. It defines and distinguishes her. It is the basis for her maternal identity, for her Marian appeal, for her subsequent miracles and, to a great degree, for her sainthood itself. In the earliest known versions of Difunta Correa’s story however, the breast-feeding miracle is entirely absent.

The folklore reports from 1921 sometimes mention a child at the breast or protected by the breasts, and one has a child sucking, but there is no reference to miraculous nourishment from the mother’s dead body. When the child in these versions clings to the breast, the sense is one of pathetic desperation alleviated only by chance, when passersby come to the rescue.

In some versions there is no child at all – Difunta Correa dies alone in the desert of sand and stone. Tragic death, rather than the miraculous breast, is what stimulates devotion; the breast-feeding embellishment later enhances the appeal.

‘‘The tragic death of this woman’’ attracted ‘‘the compassion and love of everyone who knew her story,’’ Graciella explains.

By the 1940s, however, the child’s miraculous survival at the breast began to enter the myth. Some versions are still decidedly non miraculous, like those that preceded them, and at least one culminates in the death of mother and son together.

Another version has the narrative structure in place, but the miracle won’t happen: the child ‘‘nursed futilely’’ at the dead body until saved by a passing hunter.

In other versions, however, the miracle occurs explicitly, as it does today: the child is saved by feeding at the breast of the dead mother.

It therefore appears that the miraculous breast entered the story some time between 1920 and 1940, about a century after Difunta Correa died. (These dates are flexible, and there remains the possibility of exceptions that are currently unknown.) Once it entered the myth, the attribute of the miraculous breast gradually gained prominence to become the essential feature of the Deceased identity.

Today the miraculous-breast version of the myth has superseded all others. It is also the basis for the standardized iconography.

The miracle granted to Flavio Zevallos

Bad luck struck Flavio Zevallos as he was driving a herd of cattle across the desert. A violent storm frightened the herd and it stampeded in all directions. Zevallos’s frantic search seemed futile – the cattle were nowhere to be found and he feared that everything was lost. That’s when he found Difunta Correa’s grave. He pleaded for her help in recovering the cattle and promised to build a chapel in exchange for the miracle.

When Zevallos resumed his search the following morning, he was astounded to discover his herd happily reunited and grazing in a canyon. Some of the cattle probably lifted their heads to look at him chewing. ‘‘Not a single one was missing,’’ marveled Rolando, his grandson, as he related this frequently told story. The herd made it safely to the market in Chile, where it brought a good price, and the grateful Zevallos remembered his promise.

Adobes and water were carted to Difunta Correa’s grave from nearby Caucete, and what today is a sprawling complex – a town in itself – thus had its humble beginnings around 1890.

The miracle granted to Zevallos is widely considered the first performed by Difunta Correa (excepting the miraculous breastfeeding that saved her son). It stimulated devotion among arrieros (livestock drivers) and other travelers, who, like their folk saint, faced the perils of exposure on the desert.

Difunta Correa’s miracles are on record earlier, however, beginning in 1865. A text from that date notes that:

‘‘travelers have complete faith in her miracles and invoke her in their tribulations,

and when passing by they never fail to say some prayer or deposit a silver coin in the collection box.’’

The same source observes that many murders and robberies had been perpetrated at this site in Vallecito, known as Las Peñas, because outcroppings of rock on both sides of the road provided cover for thieves who ambushed travelers.

The place was so notorious for crime that housewives, infuriated when shopkeepers tried to overcharge them, would say, ‘‘Don’t be a crook, and if you want to steal, go to Las Peñas.’’ The fortuitous location of Difunta Correa’s grave at Las Peñas gave protection to travelers precisely where it was most needed.

Difunta Correa protects one on the road, even – especially – at the place where danger is the greatest. One can travel now in peace. And can find water to quench the thirst.

The shrines

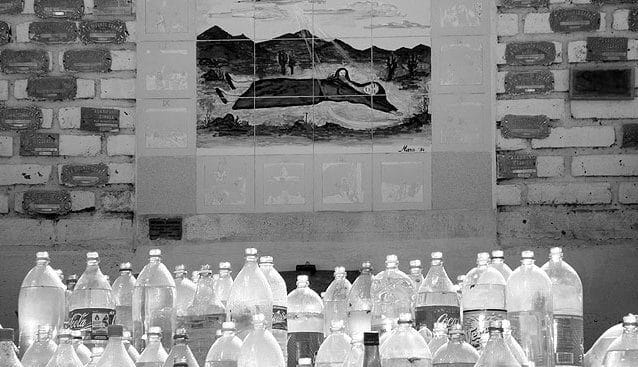

Today the highways of Argentina from one end of the country to the other, and also across the border in Chile, are spotted with roadside shrines to Difunta Correa. The shrines come in all shapes and sizes but are easily identified by their plastic water bottles all around. There are also innumerable domestic altars and shrines to Difunta Correa, many of which are open to the public.

Livestock drivers traveled over broad expanses, thereby disseminating the good news of miracles far from Difunta Correa’s original grave site at Vallecito. Shrines began appearing along the roadways as miracles proliferated in new areas, and, again,

‘‘all traveling livestock drivers who pass by on those roads have the obligation to deposit a coin, no matter how small.’’

The roadside shrines to Difunta Correa that one sees along Argentine routes today have their antecedents in this diffusion of the devotion by livestock drivers. Strong devotion among truck drivers later made a second contribution – now national – to dissemination and growth of the cult. Truckers spread the news far more efficiently than their precursors as they take to the highways with Difunta Correa’s picture, name or ‘‘Visit Difunta Correa’’ displayed prominently on their trucks.

The nineteenth-century belief in Difunta Correa’s protection of all travelers has likewise been modernized to encompass anyone who travels by car. Difunta Correa’s ill-fated journey is reversed into a safe journey for devotees. Legend, myth, belief, cult, devotion are manifestations of popular religiosity that time weaves.

Difunta Correas sanctuary in San Juan

Over the years the hill in Vallecito has become a popular destination, even a small city, with a large tourist-oriented shrine, chapels, a museum and several hospitality services. Annually more than a million people visit the sanctuary, devotees and travelers, truck-drivers, farmers or anyone else in need of a wonder. Difunta Correa is the primary object of devotion at the site, which is full of ex voto offerings of thanks for her intercession.

They come and ask for help as well as to give their respects to a place where miracles have been witnessed. In order for her to help in difficult situations people believe that they need to give something in return (ex voto, Lat.: short for ex voto suscepto, “from the vow made”), such as water bottles, car number plates, vehicle spare parts, painted signs expressing gratitude or red ribbons.

An astonishing assortment of personal objects, motorcycles, cars, clothes, jewels, kitchen appliances, boxing gloves and statues are offered to the folk saint. Thousands of license plates, hanging here and there, left by truck drivers who prayed successfully for new trucks and left their old plates for Difunta, and a wide variety of other things.

We have seen braids of hair, old and modern clocks and radios, school notebooks, plaster casts, metal votive offerings that make references to organs or parts of the human body (heart, liver, a leg), necklaces, infinite letters, clothes for the first child, pacifiers, rings, dolls, canes, little cars that represent different brands, trucks and buses with the name of the company, Objects of emotional or economic value, from stuffed animals to cars and jewelry.

Photographs: millions of them, since the beginning of the century, in black and white and in color, with people portrayed in clothes that show the passage of time and fashion and in various life circumstances: weddings, baptisms, birthdays, several photos of a child at different stages of its life, images that speak of a before and after: sick and recovered; with crutches and walking.

Photos of finished houses, businesses, soccer teams and other sports. Images of different moments in the life of a family: when they get married, the building of the house, the finished house, the birth of the children, the acquisition of a vehicle and others…

One chapel is full of enlarged reproductions of photo finishes signed by grateful jockeys, and another of diplomas left by thankful students. There is a mountain of handcrafted models of houses, dry cleaning stores and auto repair shops from entrepreneurs who sought her help and found prosperity.

The shrine has 15 chapels filled with trophies from soccer, tennis and bowling champions whose athletic dreams became reality and the wedding gowns of women whose wish of marriage was fulfilled after a visit. There are even swords from military officers who earned promotion after praying to the woman sometimes called Difunta, or Deceased, for short.

Also, there are two huge rooms where long rows of wedding dresses are hung, which are rented or can be lent in case the person who needs them does not have enough resources.

Electric guitars, accordions, a harp, a double bass, gold records and photos and posters of numerous “dancers” are displayed.

Gauchos gave offerings too: many harrows, spurs, saddles and other horse tools are exhibited.

Water bottles

Bottles of water, which pay homage to Difunta Correa’s death by thirst, have traditionally been a prominent offering at both the principal and the roadside shrines. Water is particularly significant at the Vallecito complex, which is located on the desert and has no well.

The bottles offered by devotees are poured into a cistern and provided the drinking water for visitors and the community. The shrine and the saint have the same need; water is doubly efficacious. The symbolic offering is at once practical, and the collective endeavor to irrigate the shrine of a saint who died of thirst made Vallecito an ‘‘oasis of faith’’.

As the complex grew, and after a failed initiative to construct an aqueduct, the administration began importing water from Caucete. Water is trucked in daily for the shrine and surrounding community. Thus, to a certain degree, the tradition of water-bottle offerings is conditioned by the exigencies of circumstances that are less religious than practical.

The hilltop shrine features a life-size Difunta Correa in the standard iconography, reposed with the infant nursing at her breast. This grotto and an adjacent room are filled with ex votos – primarily photographs – and Catholic images. Devotees wait in line to enter the shrine, then stand deeply moved before the statue. They sign themselves with the cross, pray, and touch the image, particularly at the miraculous breasts, and then move on to make room for others.

The hillsides sloping downward from the grotto are covered with small scale models of the homes and businesses that were acquired through Difunta Correa’s intercession. Many of these replicas are elaborate works of craftsmanship.

The models are also reminiscent of the smaller miniatures used in devotion to a mythological figure, Ekeko (Iqiqu in Aymara, ‘‘god of abundance’’), on the Andean altiplano.

During an occasion known as Alacitas, miniature houses, foods, cars, tools, home appliances, and plane tickets, among many other items, are bought and sold. The idea is that the miniature item, combined with the powers of Ekeko, will lead one to acquiring what it represents. In the Andean cases the miniatures anticipate the miracle; at the Difunta Correa shrine the ex voto acknowledge it.

Just outside of the grotto is a huge outcropping of rock, blackened with soot, around which innumerable candles burn. A pond of melted wax gradually flows down a channel into a collection vat at the bottom of the hill. Many devotees offer their candles and then linger at the hilltop. Devotees visit Difunta Correa’s shrine as though it were a church, and they find there a church like regenerative quietude.

FESTIVALS: At Difunta Correas sanctuary

During the year several festivals are carried out and many thousands of pilgrims leave expressions of their devotion. The Difunta Correa administration actively promotes events for Holy Week, Worker’s Day, the National Truckers’ Festival, and the patron-saint day of the Virgin of Carmen.

An annual event known as the Cabalgata de la Fe (which translates roughly to a horseback parade or procession for the faith, or of faith) is also hosted by the shrine.

During these festivals large crowds of pilgrims visit the shrine to request health and love, the recovery of objects or lost animals, and to pay respects to the memory of Difunta Correa.

Penance is done daily on the stairway to the hilltop shrine. One girl climbed the steps in a serpentine shimmy on her back, while balancing her offering – a bottle of water – above her chest. Others hold someone’s hand as they climb on their knees, or go it alone and break down with emotion upon arrival, hugging the statue of Difunta Correa.

The purpose of such sacrifice is to fulfill a promise made when requesting a miracle (pagar una manda) or to make an extraordinary gesture in advance. The sacrifice, like ex voto, is a public announcement of a personal devotional commitment or done/given in gratitude or devotion.

The church and Difunta Correa

The principal shrine in San Juan has enjoyed relatively peaceable relations with the Catholic Church. The Capilla de Nostra Señora del Carmen, the official church, participates in the annual fiestas.

Correa was never officially recognized as a saint – the Argentine Roman Catholic Church has long been ambivalent about her – and instead became a saint appointed by the masses. Her sacred mission is to protect travelers, but she also symbolizes the power of motherhood.

Mothers have long been particularly sacred in this part of the world, even before the Spanish conquistadors came bringing figurines of Saint Virgin Mary. The Indians who lived up and down the Andes for centuries worshipped the Pachamama, or Earth Mother, and she is still revered.

The power of motherhood

Thus in this symbolic web of interrelations, Deolinda Correa, Mary and the Church are together represented maternally, offering their love, care, protection, and spiritual nourishment to all Catholics.

The breast and milk have gone far beyond their literal meanings to become symbols of maternal care generally, now both corporal and spiritual. It is precisely this otherworldly, comprehensive nurturing of body and soul that makes Difunta Correa (like the Virgin Mary) an attractive or even necessary addition to patriarchal religion.

The most basic act of maternal sustenance, breast-feeding, retains the focus while at once it is transcendentalized and made miraculous. The male gods, who lack the capacity for maternal nurturing, are supplemented and to some degree displaced by these divine females.

Asixteenth-century indigenous myth from the same region as Difunta Correa redirects the theme of supernatural maternity by endowing a father with breast milk. The man’s wife had died during childbirth in the desert, so in desperation he put the infant to his own chest. The infant sucked futilely at the first nipple, but the other one gave milk in abundance.

The breast is miraculous because the faith is strong. In some versions of Difunta Correa’s story, similarly, right behavior earns heavenly reward:

When Difunta Correa, lost on the desert, realized that her death was imminent, she prayed that God would save her child. The miracle was granted because God recognized that the death of this exemplary wife and mother was a consequence of her love and fidelity.

Difunta Correa’s story provides a role model, particularly for mothers who are struggling for the survival of their own children. They seek otherworldly help (as did Difunta Correa) because their worldly resources are exhausted.

This quest for alleviation – almost a surrender – can come back to them unexpectedly as an enhanced burden, however, because their insufficiency is quietly implied by measure against their saint. In patriarchal interpretations, the stress falls heavily on imitating Difunta Correa’s self-sacrifice:

‘‘The mother gives up even her life so the child can live.’’

This idea has little to do with the history or even the myth – Difunta Correa dies of thirst and exhaustion, not to save her child – but the message of motherhood unto death is nevertheless conveyed to female devotees.

Difunta Correa the ideal wife

The idea of Difunta Correa as an idealized wife and mother was actively propagated beginning in the 1960s by the priest-led, male committee that developed the shrine. Today, women tend to stress the maternal qualities of Difunta Correa, while men, particularly older men, stress her fidelity and the sacrifice that she made for her husband.

Precisely the opposite argument is made in a 1946 report from San Juan.

In this version it is the shame of a sexual transgression that drives Difunta Correa into the desert: ‘‘This woman was forced to leave her home due to a grave mistake.’’ The fruit of the mistake, a boy, was born during her wanderings. Desperate and dying of thirst, Difunta Correa tried to dig for water, failed, and finally collapsed of exhaustion.

The following day her corpse and her child were found by chance. The sadness of her death was compounded by the cruelty of unknowing: had she dug another couple of feet, she would have hit water and survived. A chapel was built, with the belief that Difunta Correa

‘‘must be miraculous because she lost her life in search of what is indispensable in order to live: water.’’

Thus saintliness emerges not from exemplary performance as a wife and mother but rather from tragedy, pity, and deprivation of life’s most fundamental need. The sin of Difunta Correa’s transgression is forgiven because the penance of her death purges it. Self sacrifice is never mentioned or implied.

Syncretism and Difunta Correa

Some Chapels at the sanctuary in hold reproductions of Difunta Correa, in paintings, statuettes or prints, accompanied in all cases with different images of Holy Virgin Mary, crucifixes and official saints (San José, San Cristóbal, San Francisco and San Cayetano are the most represented).

The devotion, besides being practiced alongside Catholic faith, can incorporate or be associated with other folk saints, some non-canonic, such as the devotion for El Gauchito Gil and others belonging to the Catholic Church, most notably in the Maria Devotion – Nuestra Señora del Carmen or Virgen del Carmen. But also Cristo Rey de Caucete and other Saints.

Such incorporation can be visual and material: when effigies of the saints are placed side by side in the same altar. Or as well as narrative and theological; when tales of Difunta Correa are related to the gospels or to narratives regarding other saints, like Saint Mary.

The Virgin of Carmen or Our Lady of Luján is seen as the preferred alternative to Difunta Correa by the church. Beside the shrine a church is consecrated to this Virgin. Virgin of Carmen, is the patron of the dead (some say of the souls in purgatory) and she is also the patron of Vallecito (where the shrine is located), and many make a direct connection between the Virgin of Carmen and Difunta Correa.

They relate, for example, that Difunta Correa was wearing an image of this Virgin when she set out on her journey, or that she commended herself to the Virgin of Carmen at the moment of death and consequently her son was saved.

Folk saint of Argentina, of the roads and of the gauchos, every May 8 is celebrated in the country, the Day of Our Lady of Luján. For this reason, in the chapel of Nuestra Señora del Carmen, located in the Difunta Correa area, a mass was officiated in honor of the Virgin of Luján, and the Picture in Chapels was also blessed where the donations received by the devotees are treasured.

Religious tourism – ‘‘Sanctuary of Faith,’’ but also as a ‘‘Center of Tourist Attraction.’’

The Difunta Correa Administration, as the new management is known, has a clear priority: to develop and promote the shrine as a major site of religious tourism. The shrine also provides an important venue for distribution of artisan products of the region, such as wine and crafts. Opposition to folk devotion has thus yielded to the higher priority of steering faith in Difunta Correa toward San Juan’s economic growth. The tolerance of the shrine is the result of a change in politics, but also in perception.

What was regarded earlier as deviant Catholicism is now regarded as an opportunity for development. Perhaps Difunta Correa’s most outstanding miracle is the transformation of an inhospitable, waterless, practically useless patch of desert into new promise for San Juan’s economic development. Who could have imagined that a woman who died of thirst in the middle of nowhere would draw hundreds of thousands of tourists?

Deolinda was never canonized by the Catholic church, which regards the entire tale as nothing more than a superstition. There is little evidence of Deolinda’s existence and even less of the supposed miracles. The legend also does not say what happened to Deolinda’s son. But none of this weakens the beliefs of thousands of people who claim that Difunta Correa’s intervention resulted in miraculously answered prayers.

Her sanctuary and shrines are almost covered in thousands of plastic bottles, left by devotees with a wish for a new house, a car, luck in love, a career at FC Barcelona or, perhaps, a top position at the Vatican.

Travelers do not often cross the deserts and plains of Argentina on foot these days. But I can easily imagine a parched and weary soul, stranded far from food and water, who stumbles upon a shrine to Deolinda Correa and drinks from a water bottle left as an offering.

Whether or not this ever happens, I like to think that in death – or even as the figment of someone’s imagination – Difunta Correa now has the power to save countless thirsty travelers.

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- Graziano Frank. Cultures of Devotion Folk Saints of Spanish America. 2007. THANK YOU

- Argentines Turn Shrine Into an Oasis of Miracles

- Difunta Correa: Dictionary of Myths and Legends (Spanish)

- Gil María Laura. Una mirada antropológica sobre el mito de la Difunta Correa en San Juan, Argentina.

- http://difuntacorrea.org/

- https://sacredsites.com/americas/argentina/difunta_correa.html

- https://www.difuntacorrea.net/

- https://www.facebook.com/difuntacorreaoficial/

- https://www.ischigualasto.gob.ar/en/

- https://www.tiempodesanjuan.com/fnsdifunta-correa/2018/1/26/primer-estudio-antropologico-de-difunta-correa-28-versiones-de-la-historia-204137.html

- https://www.tiempodesanjuan.com/fnsdifunta-correa/2018/2/7/iconografa-primeas-imgenes-difunta-correa-205335.html

- Pérez Alberto Julián. Perez Julian. Santos populares argentinos. 2020.