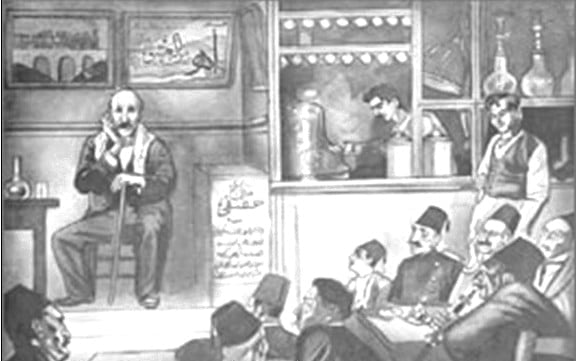

A tradition of Turkish folklore that took shape in Constantinople’s Ottoman coffeehouses is the Meddah, which sees a storyteller performing in front of the audience of the coffee shop, interpreting various dramatic or comedic roles, changing each time the tone of voice and helping himself with a cane or a handkerchief to indicate the change of scene or character.

Coffee culture: the Art of the Meddah

Ekrem Buğra Ekinci writes in: The art of the meddah; Traditional Turkish storytelling:

“The meddah sat on a tall chair for everybody to see him. He threw his printed fabric handkerchief on his shoulder, hit his stick to the ground three times, clapped his hands and began to tell a rhyme, starting:

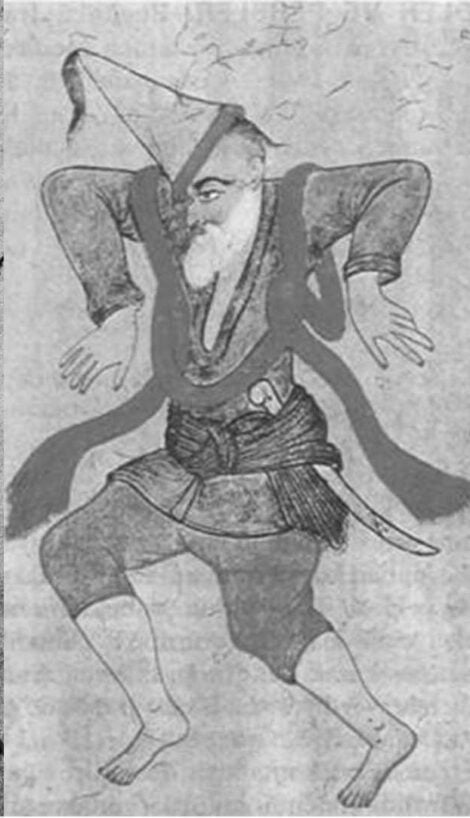

“Hak, dostum, Hak!” (It is true, my friends, Allah’s truth.) He tried to stress that his words were the truth and indirectly used to use God as a witness for what he was about to tell. Hak is one of the names for Allah in Islam. Then the meddah began telling his story. He often used the stick in his hand to either silence the crowd or imitate certain sounds or objects such as a saz, broom, rifle or horse, and he had headgear or a tambourine in his basket or jacket to be used according to the person whom the meddah was impersonating.

He would hold a cane in one hand, and a handkerchief would be placed on his shoulder. The storyteller would use the cane for several purposes. He could walk with it to become and old man, or he could use it to call the audience to silence.

Alternatively the cane could be used to produce rhythms the storyteller would incorporate into this tales. The handkerchief would be utilized as a veil to turn the teller into a woman or to cover his mouth as he mimicked sounds from nature, such as animals, rivers or trees in the wind.”

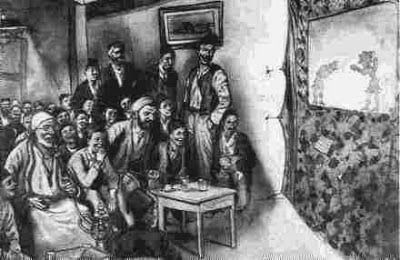

Audience participation played an important role within it. It has been noted time and again that storytellers had a tendency to halt their stories mid-way to hear the reactions of their listeners. These small breaks were accompanied by fresh cups of coffee and discussion. The meddah would typically join the listeners and ask for donations, bahşiş, during these pauses. It is likely that the continuation of the story would be affected by the temperaments and wishes of those in the coffeehouses.

A famous incident that testifies to the power of audience participation in the art of the meddah was noted down in Bursa, a city in North Western Anatolia, in 1616. The incident occurred as meddah and poet Hayli Ahmed Çelebi was telling the tale of “Bedi and Kasım.” The listeners at the coffeehouse are said to have grown excited with the progression of the story, with each listener picking a side, either Bedi’s or Kasım’s.

It is noted that the audience cheered the meddah with their fervent shouts and claps of joy each time their hero was mentioned. Apparently the storyteller Hayli Ahmed himself was passionate about Kasım and got so affected by the support of his listeners that, in a moment of passion, he knifed another storyteller that supported the opposing hero Bedi.

The themes and the stories were usually taken from true stories, modified according to the taste of the public or the political situation, stretching the characteristics of the characters until they become caricatures of themselves.

Also, traditional Turkish legends and folklore, funny real life occasions as well as stories with Islamic themes and the legends of local heroes, Persian legends, stories from 1001 Nights, Shiite and Sunni stories of saints and the histories of Ottoman sultans (the Shahnama).

Nurullah Ataç lists the type of stories that were told:

- Historical events that have left a mark in collective memory;

- Stories lived, overheard or witnessed by the storyteller;

- Written historical sources;

- Legends;

- Fairy tales;

- Scenes from popular short stories or novels;

- Characterizations, taklit (imitation);

- Shadow theatre;

- Stories made up of sayings and proverbs.

A Turkish story that could be have been told in coffeehouses would start with:

“There was, and there was not. In an earlier time, when God had many servants, when the sieve was in the chaff, when camels were town criers, when fleas were barbers, when I rocked my mother’s cradle…”

These words might seem like the opening of a surrealist novel, but they are the Turkish equivalent of “Once upon a time.”

The Tree that deceived Satan

Turkish legend has it that when Satan first came to Türkiye, or Turkey, he noticed that the cornelian cherry tree was first to bloom. Eager for the tree to bear fruit, he sat beneath the tree anxiously waiting for the fruits arrival. Unfortunately, unbeknownst to him, the cornelian cherrytree is the last to ripen.

Today the tree is sometimes called ‘Şeytan aldatan ağaci’, the tree that deceived Satan. Even though it is one of the first trees to bloom in Spring, it is one of the last to bear fruit. The Kızılcık in Turkish, usually ripen near the end of summer, and the fruit only fully ripens after it falls from the tree.

According to Evliya Celebi, accounts, not only in Istanbul but also in other parts of the Ottoman Empire, story telling was a popular entertainment. He describes the meddah in Bursa:

In Bursa there are seventy five coffee houses each capable of holding a thousand persons, which are frequented by the most elegant and learned of the inhabitants; and three times a day singers and dancers execute a musical concert in them like those of Huseyin Baykara. Their poets are so many Hassans, and their story tellers ( meddah ) so many Abulmaali. […]

All coffee houses and particularly those near the great mosque, abound with man skilled in a thousand arts (Hazer-fenn), dancing and pleasure contain the whole night, and in the morning everybody goes to mosque. These coffee houses became famous only since those of Istanbul were closed by the express command of Sultan Murad IV.”

There was no special theater building in Istanbul to exhibit plays until the 19th century. In this period, the theater plays were performed in the coffeehouses. And the artists were traveling from town to town, entertaining the patrons of the cafes with their stories:

Ottoman coffeehouses, in today’s Istanbul, capital of the Byzantine Empire before and now international metropolis in Turkey, continues this wonderful tradition: made of coffee and stories.

The art of Meddah was included in 2003 among the oral and intangible heritage recognized by UNESCO.

The most famous Turkish Storyteller has been known by different names in different places and by different people.

Many nations of the Middle East claim the Mullah as their own, however, the Mullah, like all mythological characters, belongs to all humanity.

He is called Nasreddin Hodja/ Molla Nesreddin/ Molla Ependi/ Apendi/ Afendi Kozhanasyr and Mulla Nasr Ad-Din Khodja. Nasreddin Hodjas stories spread across the Turkish Ottoman world to Persia, Arabia and Africa – and the Silk Road to China and India. Nasreddin Hodja ended up here on earthstoriez too.

Read coffee stories and tree stories from the telling tradition of Nasreddin Hodja Anecdotes.

The Nasreddin stories are known throughout the Middle East and have touched cultures around the world. That is why, the Telling Tradition of Nasreddin Anecdotes has been inscribed on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2022.

Telling tradition of Nasreddin Hodja Anecdotes – a philosopher and wiseman recognized for his wisdom and humorous analyses and representations of society and life experiences.

Although there are slight differences across communities in terms of imagery, character names and stories, the Mulla is shared as a common heritage in Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Türkiye, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.

Characterized by their wisdom, witty repartees, absurdity and element of surprise, the Nasreddin anecdotes often break with accepted norms, with the narrator finding unexpected ways out of complicated situations and always coming out as the winner by the power of word.

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- Arts of the Meddah, public storytellers.UNESCO.

- Baum Emily. Ottoman Women in Public Urban Spaces. 2012.

- Chamberlayne John. The Natural History of Coffee, Thee, Chocolate, Tobacco: Collected from the Writings of the Best Physicians and Travelers.1682.

- Çizakça Defne. Long Nights in Coffeehouses: Ottoman Storytelling in its Urban Locales.

- Coffee in Istanbul. Mehmet Efendi.

- Coffeehouse.

- Dwight, H. G. Stamboul nights. 1916.

- Ervin Marita. Coffee and the Ottoman Social Sphere. Student Research and Creative Works. 2014.

- Events Key. The Story of the Coffee House.

- From Kaffa to Istanbul: Coffee’s journey to Turkey.

- Kucukkomurler Saime, Ozgen Leyla. Coffee and Turkish Coffee Culture. Article in Pakistan Journal of Nutrition. 2009.

- Meddah – Story Teller

- Nair Sharmila. Turkish coffee, a 500-year-old tradition.In: Food News. 2015.

- Sansal Burak. Turkish coffee. All About Turkey.

- Storyteller-Giulio Magnifico (flickr)

- The Mythology and Origins of Coffee.

- The Story of Coffee.

- The Turkish Coffee Culture and Research Association.

- Turkish coffee culture and tradition. UNESCO.

- Ugur Kömeçoglu. The publicness and sociabilities of the Ottoman Coffeehouse. 2015.

- Ukers W. H. All About Coffee. The tea and coffee trade journal.1922.

- Wild Anthony. Black Gold: A Dark History of Coffee. 2005.

- Wilson Georgia. Drinkable history: the 500-year-old method to making coffee. 2014.