Discover the Aymara legend, history and folklore of the quinoa in Peru and its use in traditional culture. For millions quinoa is a major source of protein, and its protein is of such high quality that, nutritionally speaking, it often takes the place of meat in the diet.

In this Article

CHENOPODIUM QUINOA

Family: Amaranthaceae

Quechua: ayara, kiuna, kitaqañiwa, kuchikinwa, kiwicha, achita, qañiwa, qañawa, kinwa, kinuwa

Aymara: quinua,supha, jopa, jupha, juira, ära, qallapi, vocali.

Portugués: arroz miúdo do Perú, quinoa.

Chibcha: suba, pasca

Mapudungun: dawe, sawe

English: quinoa, quinua

In the Altiplano especially, quinoa is a staple food. For millions it is a major source of protein, and its protein is of such high quality that, nutritionally speaking, it often takes the place of meat in the diet. Though it often occupies a similar role to grains in dishes, researchers refer to quinoa as a “pseudocereal” from the same family as beets, chard and spinach.

A burst of colour on a monochromatic panorama, a chakra (field) of flowering quinoa plants in the altiplano is a thing of beauty. A plant ready for harvest can stand higher than a human, covered with knotty blossoms, from violet to crimson and ochre-orange to yellow.

An hour walk, along the railroad tracks to Agua Calientes, the Machu Picchu village, we found ourself in the picturesque Jardines de Mandor. Cooking together with the owner, Erwin, who served me first a homemade coffee, – meaning, home grown, home roasted, home brewed-

Showing us proud his coffee trees, Orchids and vegetable garden, we ended up staying a night, also to have a look at the waterfall on the other side of the railroad.

As for food, the restaurant was closed, but we had quinoa and beetroot, garlic and onion in our backpack. So we decided to cook together, good luck for us, we did not know how to wash quinoa the peruvian way. He washed the quinoa in plenty of water in a large bowl, kneading and rubbing it between the palm of the hands, for several minutes, rinsing removes quinoa’s natural coating, called saponin, which can make it taste bitter or soapy.

“It’s there for good reason—to ward off insects and coats every tiny grain of quinoa,—but it has a strong taste.”

At the end of the quinoa massage also little stones showed up, good, they did not end up in our mouths. We boiled it, in hot onion and garlic, like a risotto and added the red beetles and fresh herbs from the garden.

A lovely little herb caught my interest because of the minty smell, Huacatay. Huacatay is pronounced “wah-ka-day” and it’s also known as Peruvian black mint, mint marigold, wild marigold or Mexican marigold. The Huacatay plant is fairly small with tiny yellow and green flowers and spiky leaves. Its leaves are glossy green, and the leaves and the flowers produce a strong odor as it contains an essential oil. Erwin told us: “Eat cuy, cuy with Huacatay”.

We took a little to add to the quinoa dish. The taste of the Huacatay herb is somewhat a mixture of sweet basil, tarragon, mint and lime.

“We use quinoa as a vegetable, and eat the leaves, fresh or cooked. We combine it also with other foods as part of a meal, such as in a soup, or roast it and make flour, witch enriches bread, cakes and cookies.

Fermented we use it for chicha, which is considered the drink of the Incas, do you want to try?”

He comes over with a clay pot and takes two big cups.

“Chicha, is socially important in the Andes,”

said Eric.

“The Incas used it as a kind of political or social currency to build and solidify relationships with nearby lords.”

We drunk the chicha and exchanged stories, it is true chicha really connects people.

Here his recipe for CHICHA de QUINOA:

INGREDIENTES y PREPARACIÓN:

- 5 litros de agua

- 1/4 kilo de quinua

- Clavo de olor a gusto

- Canela a gusto

- Nuez moscada a gusto

- Azucar a gusto

- En una olla grande pon a hervir el agua con la canela, los clavos de olor, junto con la ralladura de la nuez moscada.

- Cuando rompa el hervor, echa la quinua lavada y deja que hierva hasta que este bien cocida (si es necesario agrega mas agua caliente).

- Cuela a travez de un paño limpio, endulza y vierte a una vasija de barro.

- Deja fermentar por dos semanas removiendolo de vez en cuando, Tapa con un paño fino para que circule el aire.

INGREDIENTS & PREPARATION

- 5 liters of water

- 1/4 kilo of quinoa

- Clove add to taste

- Cinnamon add to taste

- Nutmeg add to taste

- Sugar add to taste

- In a large pot bring the water to the boil with the cinnamon, the cloves, along with the grated nutmeg.

- When the boil breaks, pour the washed quinoa and let it boil until it is well cooked (if necessary add more hot water).

- Strain it through a clean cloth, sweeten it and pour it into a clay pot.

- Let it ferment for two weeks by moving it from time to time, Cover with a thin cloth to let the air circulate.

History and Folklore

Archaeological remains show that these “supercereal” was part of the daily diet of cultures, like Incas, Aztecs and Maya prior to the Spanish colonization, along with maize, beans or potatoes. But while the latter extended to whole earth in the next five hundred years, the “holy seed” fell into oblivion.

Closely linked to folklore and legend, quinoa and amaranth along with other dozens of varieties of plants grown with care by those first peoples were relegated to rural communities. Explorer Francisco Pizarro, in his resolve to ruin Incan culture, had quinoa fields destroyed and being replaced by other crops consumed by the foreign conquerors. Quinoa and other native crops were replaced with barley, wheat, oats, beans, and peas. While farmers were forced to work in the gold and silver mines .

Quinoa remained in quiet obscurity, raised by the Quechua and Aymara people, Inca descendants, until the 1970’s when “rediscovered” for the rest of the world.

To the Incas, quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) was a food so vital that it was considered sacred. In their language, Quechua, it is referred to as chisiya mama or mother grain.

Each year, the Inca emperor broke the soil with a golden spade and planted the first seed.

Religious festivals included an offering of quinoa in a fountain of gold to the sun god, Inti; a special gold implement was used to make the first furrow of each year’s planting; and, in Cuzco, ancient peoples worshipped entombed quinoa seeds as the progenitors of the city.

Following a visit to Colombia, the Latin American geographer Alexander von Humboldt wrote that:

quinoa was to ancient Andean societies what

wine was to the Greeks, wheat to the Romans, cotton to the Arabs.

Although more prevalent in the neighboring countries of Peru and Bolivia, quinoa has played an important role in indigenous societies throughout the Andean region, including as far south as Salta, Argentina. The history of Quinoa is rooted in South America, in the Andes region that is divided up between the countries of Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru.

Quinoa flourishes in the most hostile conditions, surviving nightly frosts and daytime temperatures upwards of 40C (104F). It is a high-altitude plant, growing at 3,600 metres above sea level and higher, where oxygen is thin, water is scarce and the soil is so saline that virtually nothing else grows.

Till today, the people still take great pride in their quinoa harvest. It is the foundation of their livelihood, and a cause for ritual and celebration. Each year, a ceremony is held to honor Pachamama, a goddess central to the ancient religion of the indigenous Andean people. Pachamama, or Mother Earth, is a fertility goddess who presides over planting and harvesting. She is the wife of Pachakamac; their children are Inti (the Sun God) and Killa (the Moon Goddess.) Together this sacred family of deities represents the four organizing principles of nature, as classified by Quechua cosmology:

- water,

- earth,

- sun, and

- moon.

These elements work hand-in-hand with the Peruvian and Bolivian farmers at any time of cultivation – from planting to harvest –, as the local communities come together to plot the land, cultivate the crops, and harvest the fruits of their labor.

Aymara Legend

The legend is retold by the Aymara anthropologist Edgar Quispe Chambi that collected myths, fables and stories, I translated it to English.

Como la Quinoa llegó a Peru

Como la Quinoa llegó a Peru

Cuenta la Leyenda que los Aymara podían hablar con las estrellas, un día una de ellas bajó a la Tierra encantada por un muchachito Aymara.

Hablaron mucho tiempo, pero ella por ser hija del cielo tuvo que marcharse con gran pena en su corazón. El chico Aymara quedó muy triste y decidió ir a buscarla volando por los cielos con la ayuda de su amigo inseparable: el condor de los andes. La encontró y estuvieron mucho tiempo juntos , ella lo alimentaba con un grano dorado, muy sabroso y nutritivo, el famoso grano de los dioses, la QUINUA.

Un día el chico quiso bajar a la Tierra a visitar a sus padres ya que los echaba mucho de menos. Ella lo despidió y le entregó el grano maravilloso, para que su pueblo pudiera cultivarlo allá en la Tierra.

Desde entonces la Quinua ha sido el fundamento alimenticio de muchos pueblos andinos, siendo un gran apoyo en la seguridad alimentaria de estos pueblos, que de otra manera no pueden acceder a los requisitos nutritivos que necesita cualquier persona para vivir.

How Quinoa came to Peru

How Quinoa came to Peru

The legend says that the Aymara could speak to the stars, one day a star descended to earth enchanted by an Aymara boy. They spoke for a long time, but she, as the daughter of heaven, had to leave with great sorrow in her heart.

The Aymara boy was very sad and decided to go and find her, flying through the skies with the help of his inseparable friend: the Andean condor.

He found her and they were together for a long time, she fed him with a very tasty and nutritious, golden grain, the grain of the gods, QUINUA.

One day the boy wanted to go down to Earth to visit his parents because he missed them very much. She dismissed him and gave him the wonderful grain, so that his people could cultivate it down on earth.

Since then Quinoa has been the food base of many Andean peoples.

As Evo Morales, the President of Bolivia stated,

“For years [quinoa] was looked down on just like the indigenous movement. To remember that past is to remember discrimination against quinoa and now after so many years it is reclaiming its rightful recognition as the most important food for life.”

Ethnobotany of quinoa:

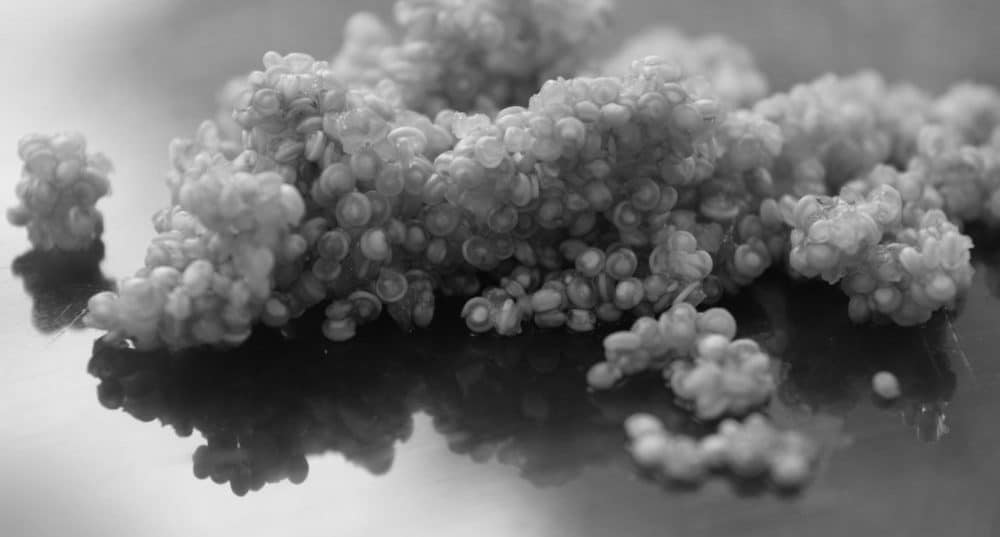

There are five basic varieties of quinoa and approximately 2000 species held in banks in Peru and Bolivia. The quinoa plant has an 8 month cycle from the sowing of the seeds to the harvest.

Quinoa has a very delicate taste, often described as nutty or earthy. Quinoa contains saponins, which are normally removed mechanically prior to being sold, or otherwise need to be carefully rinsed off prior to cooking to remove their bitter taste. Quinoa has an interesting texture that can add crunchiness to almost any recipe. Quinoa can be classified into “bitter” and “sweet” varieties that reflect the saponin content, which is much lower in the sweet varieties.

Medicinal Uses: Quinoa leaves, stems and grains: reducing swelling, soothing pain (toothache) and disinfecting the urinary tract. They are also used in bone setting, internal bleeding, and as insect repellents.

In Andean villages the coating of the quinoa, is used as an antiseptic to heal wounds.

Quinoa is potentially beneficial for human health in the prevention and treatment of disease, due it is high in anti-inflammatory phytonutrients.

Animal Feed: The whole plant is used as green forage. Harvest residue is also used to feed cattle, sheep, pigs, horses and poultry.

Pharmaceutical Use: Saponins extracted from the bitter quinoa variety have properties that can induce changes in intestinal permeability and assist in the absorption of particular medications.

Industrial Uses: Quinoa starch has excellent stability in freeze-thaw conditions, and could provide an alternative to chemically modified starches*. The starch has special potential for industrial use because of the small size of the starch grain, for example in aerosol production, pulps, self-copy paper, dessert foods, excipients in the plastics industry, talcs and anti off-set powders.

In addition to the industrial use of the quinoa grain, the saponins from the pericarp of the bitter quinoa variety have the ability to be used in different beneficial forms. The saponins extracted from the pericarp of bitter quinioa form a foam in aqueous solutions, leading to possible applications in detergents, toothpaste, shampoos, or soaps.

The use of saponin as a bio-pesticide was also shown to have potential in a successful demonstration carried out in Bolivia.

Quinoa is known for:

- Adaptability to climatic conditions, different quinoa varieties are known to grow in a temperature range from -4 degrees to 35 degrees Celsius and from sea level to 4000 meters above sea level. •

- Hardiness. Certain quinoa varieties can grow under difficult conditions, as they are drought tolerant and resistant to salinity. Quinoa grows in highlands and in lowlands, thus proving its versatility as a real climate smart crop.

- Low production costs.

- In the Andes, production remains family-based and mostly organic, conferring an elevated fair-trade/super food’s image.

- Environmentally friendly: Quinoa’s great adaptability to climate variability and its efficient use of water make it an excellent alternative crop in the face of climate change.

- Praised by NASA as an ideal crop for inclusion in possible future long-term space missions when crops would need to be grown on a spacecraft.

Note: This is about the Aymara legend, history and folklore of the quinoa in Peru and its use in traditional culture.

This post does not contain medical advice.

Please ask a health practitioner before trying therapeutic products new to you.

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- Ahamed, T.; Singhal, R.; Kulkarni, P.; Pal, M. 1998. A lesser-known grain, Chenopodium quinoa: review of the chemical composition of its edible parts. Food and Nutrition Bulletin. Vol. 19. No. 1. The United Nations University.

- Montoya, L.; Martínez, L.; Paralta, J. 2005. Análisis de las variables estratégicas para la conformación de una cadena productiva de la quinua en Colombia. Journal Innovar. Edit. Unibiblos: v. 25, p. 103-119.

- U.S.-E.P.A. 2002. Saponins of Chenopodium quinoa (097094) Fact sheet. Regulating Pesticides.

- https://www.fao.org/quinoa-2013/what-is-quinoa/origin-and-history/en/?no_mobile=1

- A lesser-known grain- Chenopodium quinoa: Review of the chemical composition of its edible parts. N. Thoufeek Ahamed, Rekha S. Singhal, Pushpa R. Kulkarni, and Mohinder Pal in: Food and Nutrition Bulletin Volume 19, Number 1, 1998.

- Center for New Crops & Plant Products, at Purdue University.

- Chenopodium quinoa – An Indian perspective. Bhargava A, Shukla S and Ohri D., Crops and Products, Volume 23, 2006.

- Erdos Jordan. Quinoa, Mother Grain of the Incas.

- La Quinoa: El Tesoro Olvidado de los Incas

- Structures of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) saponins, Food and Nutrition Bulletin Volume 19, Number 1, 1998.

- *The video was directed by Jorge Carmona and produced by Celia Barreda. The story is by Gregorio Ordoña, and the music by Lucho Quequezana.