The Italian name tazzina, ta-ZZ-EE-naa, – the espresso cup – is not so much the diminutive of tazza,Ta-ZZ-Ah, but it is due to an Italian: Luigi Tazzini. He designed the espresso cup with handle as we know it today. It was at the beginning of the eighteenth century, with the spread of exotic drinks, like, coffee, tea, and chocolate, when European tableware as we know it today was born. The tiny cup with a handle placed in a saucer with the same decoration found it’s way into households and coffeehouses in Turkey, Italy and elsewhere.

In this Article

Porcelain cups were historically manufactured in Japan and China, frequently the same were intended for both coffee and tea.

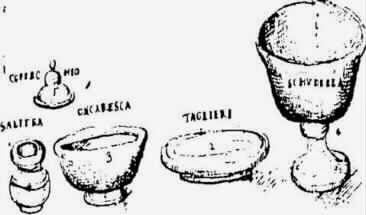

Piccolpassos bowls

In the mid-16th century Cipriano Piccolpasso distinguished according to the dimensions:

“tazzoni o confettiere”, “cups or confectioners” (similar to large vases with lids to contain sweets);

“cups” and “bowls” all without handles. Piccolpassos treatise Li tre libri dell’arte del vasaio, Three books of the potter’s art, describe the art of ceramics. Published in print for the first time in Rome in 1857-58, it is an extraordinarily source on the history of artistic ceramics and techniques used in Italy during the Renaissance.

CC0

He also uses the words cups along with small bowls – plural – for tazzine e gli schudelini, when describing the production method.

There is no complete clarity on the difference between the various types, but it seems that these cups were not equipped with a handle. The dishware was often decorated and the patterns became finer and more ornate as pottery art developed.

Saucer – piattino

Nicolas de Blegnys, book: Le Bon usage du the’ du caffe’ et du chocolat pour la preservation & pour la guerison des maladies, first printed in Paris, 1686, shows fine finjan cups with saucers on a platau.

Legendary, the saucer was an idea born from the need of a girl who had difficulty serving hot tea, with a cup without a handle, to her father. She then went to a potter and asked him to create a plate.

In the 18th century, cups with handles and saucers took hold in Europe. Cups with a saucer with the same decoration appeared, which not only served as a support, but were also used to cool the coffee: the coffee was poured and drunk right from the saucer. In India it is still in use, when drinking filter Kapi and tea.

As traditions change, drinking coffee from the saucer over time became bad manners, so much so that it was considered offensive.

Luigi Tazzini and his tazzinin with handle

The genius of Luigi Tazzini molded in porcelain gave life to today’s espresso cup with a handle.

With the advent of coffee, tea and chocolate, the “tazzina” was born, according to this legendary story it does not seem to be the diminutive of cup (-ina is an Italian suffix meaning rather small).

It seems that the Italian name comes from its creator, Luigi Tazzini, a painter of Lombard origin who was trained at the Brera Art Academy in Milan and later artistic director of Italian Richard-Ginori Ceramic Society, one of the oldest porcelain manufacture still active in Italy.

Luigi Tazzini visited the Paris Exhibition of 1900 and brought Art Nouveau back to the manufactury in Doccia: peacocks, flowers on long stems, flowing plants and female figures. From 1896 to 1923 Tazzini was artistic director of the company and presented his innovations at the Turin International Exhibition 1902; in 1903 in Milan and in 1907 in Bologna.

Luigi Tazzinis creativity materialized in adding a handle to the traditional bowls of the time.

There were various versions named by the Milanese according to the use to which they were intended:

el tazzinin per il caffè – the cup for the coffee,

el tazzin per il vino – the cup for the wine,

a tazzinetta per il caffèlatte – cup for caffè latte, milk coffee

a tazzina per la pasta e fagioli – cup for pasta and beans, a staple of Italian peasant cooking

Soon Luigi Tazzini’s tableware creations – as Roberto Bagnera recalls in his booklet “Milan at the table with history” – began to find their way onto the Italian table culture.

At the beginning of the 18th century, with the spread in the West of coffee, tea and chocolate the cup was born almost similar to how we know it today. Coffee was initially served in cups without a handle, in Arab style.

Around this time, Europeans began to imitate and produce fine Chinese porcelain, Fine Bone China.

Production of hard-paste porcelain in Italy: Manifattura di Doccia

The name Ginori 1735 refers to the eighteenth-century origins of the porcelain company, when the Marquis Carlo Andrea Ginori launches the future Manifattura di Doccia in Doccia, in the villa of the family estate.

Manifattura di Doccia invented the ‘stencil’ technique to decorate their porcelain items, compensating for its still scant painting skills. Carl Wendelin Anreiter von Zirnfeld, painter and chief decorator at the Du Paquier factory, came to Doccia from Austria in 1740 and marked the beginning of brush-painted decoration called ‘Pittoria’, which is still the hallmark of Ginori today.

Ceramic is used as a generic term for porcelain, stoneware, majolica, terracotta and so forth, whose main differences lie in blends and temperatures. The three main ingredients include kaolin, feldspat and quartz. Rough proportions call for 2:1:1 but the nuts and bolts remain a secret defined by school, district, and tradition — much like grandma’s Moka pot, which follows just one ritual, and yet everyone seems to have their own take.

The resulting material, Clara Borrelli writes in Lampoon, the Honesty issue, would be dough-like in consistency, worked under pressure in order to make a series of plates, while porcelain, by default, came in liquid form, allowing for artistic elaborations.

There are two ways to mold: the first, and more advanced, is industrial, and meant for everyday dishes, which we use as a reference for our porcelain work. It’s a pressure mechanism for curved and round shapes, on a horizontal plane. A system of pumps and syphons, like the watering-system of a garden, or the work of a local plumber — every work station with its own faucet and a gun-shaped extension to fill in the molds.

The second is classic molding, the way Canova used plaster, or, more boldly, the way Michelangelo used stone, sculpting by hand. From the plaster department comes the model through which a simple negative obtains the mold: a cube containing the impression of the artifact and the artistic production by hand.

The crudo enters the first oven, which extends nearly 80 meters long, and where temperatures reach up to 1000 degrees. Inserted by morning and extracted by night, the crudo becomes what is known as biscotto (bisque): a solid but porous material. The biscotto is then dunked in a mixture called vetrina (glaze) that will give it its translucent finish, and is prepared for the second oven, which burns at 1400 degrees. After this second process, the artifact is known as bianco, or cotto forte: the porcelain is shiny and translucent, the final product before any coloration.

At this point, the artifacts are colored, and head back into the oven. Cooking for color, temperatures are kept below the 1400 degrees of the bianco cotto finito, leaving its physics stable and the object solid: every time an object is cooked in the oven, it’s subject to stress, and hardened, making it more fragile.

The brightest colors are those that cook at 800 degrees: they’re called ‘third-fire’ colors, and they stay on top of the enamel. They’re strong and bright and range from gold, cobalt blue to burgundy, green, and black — jewel tones, that refer to lapis lazuli, a pigment originating from a blue gemstone.

At each workstation, masters of the craft bring ideas from the style department to life, which are developed through books, aesthetic research, and trial and error. But it’s the artisan that has the ultimate say in a project with logistical problems, adjusting as they go. What artisans know, they learned from those before them, and each idea is the result of manual testing and new manual abilities, Clara Borrelli knows.

Tazza or Demitasse

In the dictionaries we read that ‘Tazza‘ is a small, low, round container, with a mouth wider than the bottom, with or without a lid, with a handle, and a low foot.

Tazza, borrowing from Arabic tassah فِنْجَان, from Persian tasht “cup, saucer,”Italian tazza, Spanish taza “cup.”

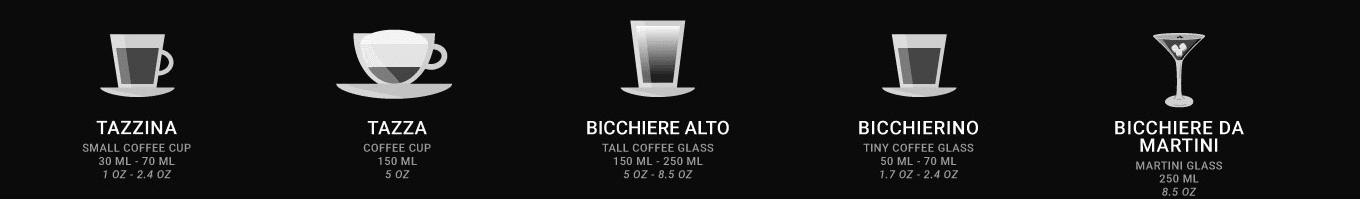

German Tasse is derived from French Demitasse. Demi-tasse (dem-E-tas) is a “small coffee cup,” 1842 from French, literally “half-cup,” from demi + tasse “cup,” an Old French borrowing from tassah “cup, saucer.” This small coffee cup holds about 2 to 3 fluid ounces (60 to 90 milliliters). They are half the size of a cappucino coffee cup, hence the name “half cup.”

In addition to meaning half cup, the term demitasse may also refer to the measurement of coffee in a demitasse cup or glass. Most demitasse come with a saucer.

The tazzina da coffè or demitasse of today, is known with other names also:

- Demi cup

- Kahve Fincan (Turkish)

- Šáleček pohár (Czech)

- Mokkatasse (German)

- Copo demitasse (Portuguese)

- Copa tacita or pocillo (Spanish)

History: A tiny coffee cup and espresso, a love story

Marco Polo first encountered porcelain at the court of the Mongolian emperor, Kublai Khan. He was mesmerized by the luminescence of the material — there was no written record of it anywhere in Europe at the time — comparing it to Mother of Pearl, like the shells found in the depths of Asian seas and used as money.

He wrote in Book of the Marvels of the World:

Gold is found here; but the small money is of porcelain, which circulates in all these provinces.

As coffee, tea and chocolate spread to Europe, Chinese porcelain cups were gradually replaced by Western styles and products, reflecting the spread of coffee from the Ottoman Empire to Central and Western Europe.

Clara Borrelli states: The Dutch East India Company introduced European courts to porcelain in the 16th century, where chinoiserie became very much in vogue as a coveted addition to any cabinets de curiosité and a prized centerpieces to display on tables or furniture. Owning a piece of porcelain was a mark of social status before it became a business, when local craftsmen found out how it was made.

La tazzina e l’espresso – functionality & a design object

Working on materials and product design for food and drink means giving life to ideas that must necessarily combine beauty and functionality. In the case of espresso, for example, the cup is not just a design object. But it also has the task of not letting the drink cool down too quickly.

A professional coffee cup has to be made of hard, feldspathic porcelain, which is fired at a temperature of approximately 1400°C. This material is very resistant to wear; it is hygienic and retains its shiny appearance for a long time. It is also able to conduct and maintain heat to keep the coffee at the right temperature.

The Italian Espresso National Institute (INEI) recommends serving espresso in a white china cup holding 50−100 ml. This is the only cup whereby it is possible to fully appreciate the look of an excellent froth, the precious smell and the warm and smooth taste of espresso.

A soft, rounded interior allows the crema to land gently and retain its texture, heat, and visual appeal. Until 1990s, in Italy, espresso cups were mostly available in plain white. At most, some featured a logo for decoration.

The characteristics of the perfect tazzina, coffee cup:

The shape must be a truncated cone to enhance the aroma of the coffee, rounded internally and with an egg-shaped base to guarantee compactness to the drink and good sealing of the crema.

The lower part of the cup must be thicker and the upper part thinner, because the temperature of the coffee must initially drop, but then must remain high during the sensory experience of tasting. The upper part is slimmer, moreover, to facilitate contact with the lips.

Espresso artistic little cups

Illy did marry art and espresso. Its groundbreaking decision to commission architect and designer Matteo Thun to re imagine the espresso cup lead to the creation of Illy’s Art Collection sets.

Matteo Thun, architect and designer, in 1991, created the white illy coffee cup, as the perfect espresso container, with the aim of enhancing the sensations of every sense involved in tasting.

Space espresso coffee

Between 2015 and 2017, the first espresso coffee machine (ISSpresso) designed for use in space was produced for the International Space Station by Argotec, Lavazza and the Italian Space Agency (ASI). For the use in space a special coffee cup named zero-g espresso cup, was also created.

Obviously the history of the tazzina does not stop here. From the typical English and American “mug” (= large cup) to cappuccino cups, there are many variations of the tazzina available.

The visual appeal of espresso — with its dark liquid and golden brown crema — presents itself beautifully in a glass. It also retains heat well, but it may become quite hot to touch.

The cup of coffee is an iconic symbol of coffee culture and is never missing in Italian homes, bars and coffeehouses, this makes it something exceptional. The tiny coffee cup is an apparently ordinary product, but which upon careful observation reveals attention to art and design, traced along the thin boundary that makes an object both recognizable and, ultimately, common.

The iconic Tazzina, the small, elegant espresso cup and saucer, is widely perceived as the quintessential coffee vessel. Artists, architects and designers of yesterday and today have committed themselves to designing the most varied coffee cups. A delicious caffè drunk from a shiny, thin and elegant fine bone china cup is still unbeatable for us.

When you are in Trieste the espresso is served in a “bicerin” little glass, in Milan the word “tazzin or chichera” is used, and when in Naples it might be “O’ tazzulella”.

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

The history of coffee is an extraordinary study. If you would like to learn more about it, I heartily recommend the book, All About Coffee, by William Ukers. Written in 1928, it will delight you with detail.

- Allegra World Coffee Portal www.worldcoffeeportal.com

- Allen Lee Stewart. Devil’s Cup. A History of the World According to Coffee. 1999.

- Artusi Pellegrino. Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well, transl. Murtha Baca and Stephen Sartarelli. 2003.

- Biderman Bob. A people’s history of coffee and cafés. 2013.

- Brosh, Na’ama. 2002 “Coffee Culture.” Catalogue for an exhibition of the same title, The Israel Museum: Jerusalem.

- Café Culture Magazine www.cafeculturemagazine.co.uk

- Carosello Bialetti: la caffettiera diventa mito https://www.famigliacristiana.it/video/carosello-bialetti-moka-mito.aspx

- Cociancich Maurizio. Storia dell’ espresso nell’Italia e nel mondo. 100% Espresso Italiano. 2008.

- Comunicaffe International www.comunicaffe.com

- Davids Kenneth. Espresso Ultimate Coffee. 2001.

- De Crescenzo Luciano. Caffè sospeso. Saggezza quotidiana in piccoli sorsi. 2010.

- De Crescenzo. Luciano. Il caffè sospeso.

- Eco Umberto. “La Cuccuma maledetta” in Agostino Narizzano, Caffè: Altre cose semplici. 1989.

- Global Coffee Report www.gcrmag.com

- Gusman Alessandro. Antropologia dell’olfatto. 2004.

- Hayes, J. W. 1992 Excavations at Saraçhane in Istanbul. Volume 2: The Pottery. Dumbarton Oaks,Washington, DC.

- Hippolyte Taine, wrote in, Italy: Florence and Venice, trans J. Durand. 1869.

- http://90905.homepagemodules.de/t155f59-Cappuccino-Kapuziner-Melange-oder-wie-jetzt.html

- http://archivioceramica.com/CERAMISTI/T/Tazzini%20Luigi.htm

- http://archivioceramica.com/fabbriche/R/Richard-Ginori.htm

- http://archivioceramica.com/FABBRICHE/R/Richard-Ginori.htm

- http://www.archiviograficaitaliana.com/project/322/illycaff

- http://www.baristo.university/userfiles/PDF/INEI-M60-ENG-Public-Regulation-EICH-v4-1.pdf

- http://www.coffeetasters.org/newsletter/en/index.php/category/a-baristas-life/

- http://www.coffeetasters.org/newsletter/it/index.php/il-galateo-del-caffe/01524/

- http://www.culturaacolori.it/fascismo-contro-le-parole-straniere/

- http://www.espressoitaliano.org/en/The-Certified-Italian-Espresso.html

- http://www.inei.coffee/en/Welcome.html

- https://archiviostorico.fondazionefiera.it/entita/585-bialetti-industrie

- https://bialettistory.com/

- https://buongiornoceramica.it/eventi/archivio-della-ceramica-sestese/

- https://caffeaiello.cz/blog/curiosity/history-of-the-traditional-espresso-cup/

- https://cdn.intechopen.com/pdfs/55623.pdf Severini Carla. Derossi Antonio. Ricci Ilde. Fiore Anna Giuseppina. Caporizzi Rossella. How Much Caffeine in Coffee Cup? Effects of Processing Operations, Extraction Methods and Variables

- https://coffeelounge.delonghi.com/it/news/la-storia-della-tazzina/

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carlo_Ginori

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Teacup

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caff%C3%A8_sospeso

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coffee_cup

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drip_coffee#Cafeti%C3%A8re_du_Belloy

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ISSpresso

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Italian_meal_structure

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neapolitan_flip_coffee_pot

- https://etd.adm.unipi.it/t/etd-03182015-222130/

- https://filicorizecchini.us/blogs/news/the-curious-story-of-the-coffee-cup

- https://hal.science/hal-00618977/document

- https://hub.jhu.edu/magazine/2023/spring/jonathan-morris-coffee-expert/

- https://ineedcoffee.com/the-story-of-the-bialetti-moka-express/

- https://it.glosbe.com/it/mis_mil/tazzina%20da%20caff%C3%A8

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caff%C3%A8

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caff%C3%A8#Risvolti_etici_e_sociali

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napoletana

- https://italofonia.info/la-politica-linguistica-del-fascismo-e-la-guerra-ai-barbarismi/

- https://italysegreta.com/italian-hospitality-the-invite/

- https://lampoonmagazine.com/article/2022/04/30/ginori1735-porcelain/

- https://library.ucdavis.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/LangPrize-2017-ElizabethChan-Project.pdf

- https://localfoodeater.com/tag/luigi-tazzini/

- https://localfoodeater.com/tag/tazzini/

- https://materceramica.org/poi/archivio-della-ceramica-sestese/

- https://medium.com/@cosmiccoffeemarketplace124/the-history-of-coffee-mugs-from-ancient-times-to-modern-designs-fcefe9774fcf

- https://memoriediangelina.com/2009/08/11/italian-food-culture-a-primer/

- https://mostre.cab.unipd.it/marsili/en/130/the-everyday-eighteenth-century

- https://museoginori.org/magazine/gio-ponti-e-la-richard-ginori

- https://napoliparlando.altervista.org/cuccumella-la-caffettiera-napoletana/

- https://newsoggi.wordpress.com/2014/07/13/la-tazzina-del-caffe-12/

- https://northernwilds.com/history-in-a-cup-of-tea/

- https://prochet.blogspot.com/2015/01/quante-storie-per-una-tazzina.html?m=1#!

- https://raccoltestorichedibrera.altervista.org/category/pubblicazioni/?doing_wp_cron=1698766015.6337399482727050781250

- https://specialcoffeeitaly.com/barista-espresso-coffee-machine/

- https://specialcoffeeitaly.com/italian-breakfast-cappuccino-cornetto/?_gl=1*1gjfoya*_ga*OTE0MDM2ODM5LjE2OTMzNjE5OTg.*_ga_2HTE5ZB0JS*MTY5MzM2MTk5Ny4xLjEuMTY5MzM2Mjk0NS4wLjAuMA../

- https://specialcoffeeitaly.com/what-came-first-the-italian-bar-or-coffee/

- https://tazzando.com/l-evoluzione-delle-tazze/

- https://themokasound.com/

- https://unamoreditazza.altervista.org/artisti-delle-tazze/

- https://uwyoextension.org/uwnutrition/newsletters/understanding-different-coffee-roasts/

- https://www.academia.edu/38111827/Gio_Ponti_and_Richard_Ginori

- https://www.adir.unifi.it/rivista/1999/lenzi/cap2.htm

- https://www.antiquanuovaserie.it/fiori-e-decori-in-quel-di-meissen/

- https://www.bialetti.co.nz/blogs/making-great-coffee/using-bialetti-coffee-makers

- https://www.bialetti.com/ee_au/our-history?___store=ee_au&___from_store=ee_en

- https://www.bialetti.com/it_en/inspiration/post/ground-coffee-for-moka-should-never-be-pressedhttps://www.brepolsonline.net/doi/pdf/10.1484/J.FOOD.1.102222

- https://www.britannica.com/art/pottery/Early-Islamic

- https://www.britannica.com/technology/glass

- https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/culture/2015-12/23/content_22785220.htm

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/Amsterdam/2014.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/Milan/2013/Gallery/Other/Amalia-Chieco

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/NewYork/2016.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/NewYork/2017.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/NewYork/2018.aspx

- https://www.coffeeartproject.com/TheCollection/NewYork/2019.aspx

- https://www.coffeeresearch.org/science/aromamain.htm

- https://www.coffeereview.com/coffee-reference/from-crop-to-cup/serving/milk-and-sugar/

- https://www.comitcaf.it/

- https://www.comunicaffe.it/luigi-tazzini/

- https://www.comunicaffe.it/tazza-luigi-tazzini/

- https://www.comunicaffe.it/tazzina-del-caffe-storia/

- https://www.ecf-coffee.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/European-Coffee-Report-2022-2023.pdf

- https://www.espressoitalianotradizionale.it/

- https://www.euronews.com/culture/2022/02/15/the-italian-espresso-makes-a-bid-for-unesco-immortality

- https://www.faema.com/int-en/product/E61/A1352IILI999A/e61-legend

- https://www.finestresullarte.info/en/works-and-artists/the-bialetti-moka-the-ultimate-romantic-design-object

- https://www.finestresullarte.info/opere-e-artisti/moka-bialetti-oggetto-design-ultimi-romantici

- https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/leisure/food/2022/02/15/italy-woos-unesco-with-magic-coffee-ritual/

- https://www.gaggia.com/legacy/

- https://www.gamberorossointernational.com/news/coffee-10-false-myths-to-dispel-on-the-beverage-most-loved-by-italians/

- https://www.gcrmag.com/calls-to-review-price-structure-of-italian-espresso/

- https://www.ginori1735.com/us/en

- https://www.ginori1735.com/us/en/history

- https://www.giornaledelcaffe.it/category/curiosita/

- https://www.giornaledelcaffe.it/storia/la-curiosa-storia-della-tazzina-di-caffe/

- https://www.giornaledelcaffe.it/storia/storia-del-cucchiaino-da-caffe-da-uno-strumento-di-nicchia-ad-un-arnese-universale/

- https://www.granaidellamemoria.it/index.php/it/archivi/caffe-espresso-italiano-tradizionale

- https://www.illy.com/en-us/coffee/coffee-preparation/how-to-make-moka-coffee

- https://www.illy.com/en-us/coffee/coffee-preparation/how-to-use-neapolitan-coffee-maker

- https://www.ilpost.it/2011/06/08/itabolario-bar-1897/

- https://www.invaluable.com/blog/limoges-china/

- https://www.invaluable.com/blog/wedgwood-china/

- https://www.italienaren.org/tradizioni-italiane-caffe-in-ginocchio/

- https://www.itstuscany.com/en/bar-where-the-word-comes-from/“Cafe Hawelka”, John A. Irvin

- https://www.kobo.com/hk/en/ebook/object-studies

- https://www.lacucinaitaliana.it/article/perche-il-caffe-si-serve-nella-tazzina-consigli-galateo-esperto/

- https://www.lastampa.it/verbano-cusio-ossola/2016/02/17/news/le-ceneri-di-renato-bialetti-nella-sua-moka-con-i-baffi-1.36565348/

- https://www.lavazza.com/en/coffee-secrets/neapolitan-coffee-maker

- https://www.lavazzausa.com/en/recipes-and-coffee-hacks/making-espresso-at-home

- https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/third-wave-coffee-meets-tradition-neapolitan-maker-bruno-lopez

- https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/opere-arte/schede/XC080-00271/

- https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/ricerca/?current=4&q=tazzina+caff%E9&a=202#

- https://www.mumac.it/we-love-coffee-en/be-our-guest-en/progettazione-e-rito/?lang=en

- https://www.politesi.polimi.it/handle/10589/140780

- https://www.pressrepublican.com/news/lifestyles/tea-cups-steeped-in-rich-history/article_d35b8d14-d3bb-5898-8972-0267b47afadb.html

- https://www.quartacaffe.com/images/pdf/carta-dei-valori.pdf

- https://www.repubblica.it/il-gusto/2021/07/26/news/caffe_il_piu_clamoroso_equivoco_gastronomico_d_italia-311835974/

- https://www.taccuinigastrosofici.it/ita/news/contemporanea/semiotica-alimentare/print/Pop-cibo-di-sostanza-e-circostanza.html

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00076791.2020.1801643

- https://www.thehistoryoflondon.co.uk/coffee-houses/

- https://www.wholelattelove.com/blogs/articles/history-of-the-coffee-mug

- https://www.wien.gv.at/english/culture-history/viennese-coffee-culture.html

- Illy Andrea. Viani Rinantonio. Furio Suggi Liverani. Espresso Coffee. The Science of Quality. 2005.

- International Coffee Organization www.ico.org

- it.wikiquote.org (https://it.m.wikiquote.org/wiki/Voci_e_gridi_di_venditori_napoletani)

Voci e gridi di venditori napoletani - Kerr Gordon. A Short History of Coffee. 2021.

- La cremina per il caffè: come farla bene. https://www.lacucinaitaliana.it/news/cucina/come-fare-la-cremina-del-caffe/

- Leonetto Cappiello – Wikipedia page on the creator of the 1922 poster La Victoria Aduino.

- Markman Ellis. The Coffee House. A Cultural History. 2005.

- Mennell Stephen. All Manners of Food. Eating and Taste in England and France. 1996.

- Montanari Massimo. Il riposo della polpetta e altre storie intorno al cibo. 2011.

- Montanari Massimo. Il sugo della storia. 2018.

- Morris Jonathan. A Short History of Espresso in Italy and the World. Storia dell’espresso nell’Italia e nel mondo. In M. Cociancich. 100% Espresso Italiano. 2008.

- Morris Jonathan. Coffee: A Global History. 2019.

- Morris Jonathan. Making Italian Espresso, Making Espresso Italian.

- National Coffee Association www.ncausa.org

- Pazzaglia Riccardo. Odore di Caffe’. 1999.

- Pendergrast Mark. Uncommon Grounds. The History of Coffee and How It Transformed Our World. 2019.

- Scaffidi Abbate Mario. I gloriosi Caffè storici d’Italia. Fra storia, politica, arte, letteratura, costume, patriottismo e libertà. 2014.

- Schnapp Jeffrey. The Romance of Caffeine and Aluminum. Critical Inquiry. 2001.

- Sibal Vatika. Food: Identity of culture and religion. 2018.

- Specialty Coffee Association www.sca.coffee

- Spieler Marlena. A Taste of Naples. 2018.

- Tea and Coffee Trade Journal www.teaandcoffee.net

- The Long History of the Espresso Machine. www.smithsonianmag.com

- The Pleasures and Pains of Coffee by Honore de Balzac

- The relaxation ritual https://themokasound.com/

- Tucker, Catherine M. Coffee Culture: Local Experiences, Global Commensality, Society and Cuture 2011.

- World Coffee Research www.worldcoffeeresearch.org