The Juniper Tree or The Almond Tree is a German fairy tale, that revolves around infanticide, cannibalism, and gruesome revenge, abusive (step-) mothers, absent fathers, child abuse, talking animals and biblical symbolism.

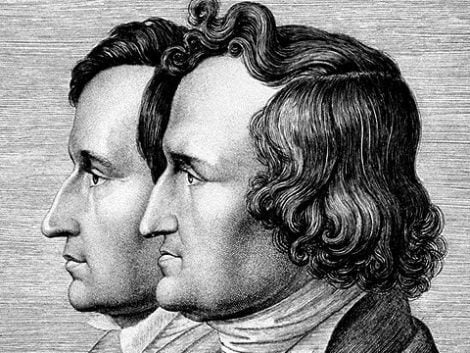

Philipp Otto Runge first recorded the fairy tale in 1845 under the title “Von den Machandelboom,” or “On the Almond Tree.”

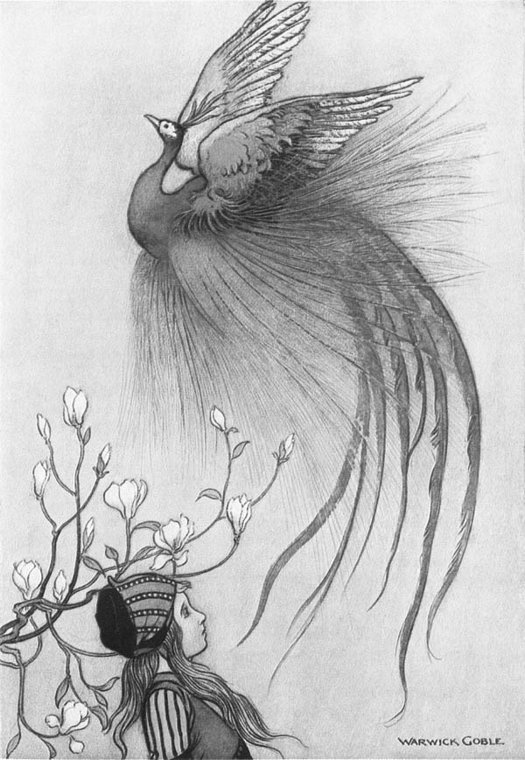

Public domain, Flickr commons license, edited.

The Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm brothers were inspired by the painter’s original adaptation of The Juniper Tree, so 1853 it was published in the “Deutsches Märchenbuch” as “Der Wacholderbaum,” which we translate as “The Juniper Tree.”

The story in the Grimm collection is in Low German or Plattdeutsch, from northern Germany that shares linguistic features with English and Dutch as well as standard High German.

It was believed until the early 1970s that the Brothers Grimm re-adapted various oral recountings and fables heard from local peasants and townspeople in order to write their well-known fairy tales. However, various critics argue that this assumption is false.

In his essay “On Fairy-Stories”, J. R. R. Tolkien cited The Juniper Tree as an example of the evils of censorship for children; many versions in his day omitted the stew, and Tolkien thought children should not be spared it, unless they were spared the whole fairy tale:

The beauty and horror of The Juniper Tree (Von dem Machandelboom), with its exquisite and tragic beginning, the abominable cannibal stew, the gruesome bones, the gay and vengeful bird-spirit coming out of a mist that rose from the tree, has remained with me since childhood;

and yet always the chief flavour of that tale lingering in the memory was not beauty or horror, but distance and a great abyss of time, not measurable even by twe tusend Johr. [sic]

Without the stew and the bones – which children are now too often spared in mollified versions of Grimm * – that vision would largely have been lost. I do not think I was harmed by the horror in the fairytale setting, out of whatever dark beliefs and practices of the past it may have come.

Such stories have now a mythical or total (unanalysable) effect, an effect quite independent of the findings of Comparative Folklore, and one which it cannot spoil or explain;

they open a door on Other Time, and if we pass through, though only for a moment, we stand outside our own time, outside Time itself, maybe. [sic]

* They should not be spared it – unless they are spared the whole story until their digestions are stronger.

In Alfred and Elizabeth David‘s essay, “A Literary Approach to the Brothers Grimm,” they interpret “The Juniper Tree” as “folk literature for inspiration.”

They believe that the nature and native culture presented in most Grimm fairy tale inspires other artists in their literary endeavors. In “The Juniper Tree,” this theme of nature is present.

The Grimm Brothers use the juniper tree as a life source for the mother and the son. The use of nature as a life source inspired other literary work such as “Briar Rose”.

The Juniper Tree

The Juniper Tree

Long ago, at least two thousand years, there was a rich man who had a beautiful and pious wife, and they loved each other dearly. However, they had no children, though they wished very much to have some, and the woman prayed for them day and night, but they didn’t get any, and they didn’t get any.

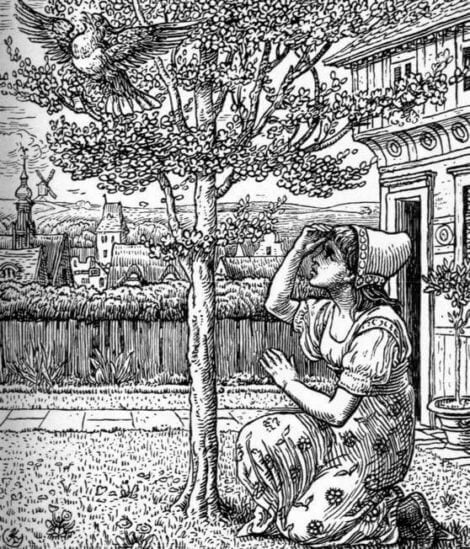

In front of their house there was a courtyard where there stood a juniper tree. One day in winter the woman was standing beneath it, peeling herself an apple, and while she was thus peeling the apple, she cut her finger, and the blood fell into the snow.

“Oh,” said the woman. She sighed heavily, looked at the blood before her, and was most unhappy. “If only I had a child as red as blood and as white as snow.” And as she said that, she became quite contented, and felt sure that it was going to happen.

Then she went into the house, and a month went by, and the snow was gone. And two months, and everything was green. And three months, and all the flowers came out of the earth. And four months, and all the trees in the woods grew thicker, and the green branches were all entwined in one another, and the birds sang until the woods resounded and the blossoms fell from the trees.

Then the fifth month passed, and she stood beneath the juniper tree, which smelled so sweet that her heart jumped for joy, and she fell on her knees and was beside herself. And when the sixth month was over, the fruit was thick and large, and then she was quite still.

And after the seventh month she picked the juniper berries and ate them greedily. Then she grew sick and sorrowful. Then the eighth month passed, and she called her husband to her, and cried, and said,

“If I die, then bury me beneath the juniper tree.”

Then she was quite comforted and happy until the next month was over, and then she had a child as white as snow and as red as blood, and when she saw it, she was so happy that she died.

Her husband buried her beneath the juniper tree, and he began to cry bitterly. After some time he was more at ease, and although he still cried, he could bear it. And some time later he took another wife.

He had a daughter by the second wife, but the first wife’s child was a little son, and he was as red as blood and as white as snow. When the woman looked at her daughter, she loved her very much, but then she looked at the little boy, and it pierced her heart, for she thought that he would always stand in her way, and she was always thinking how she could get the entire inheritance for her daughter.

And the Evil One filled her mind with this until she grew very angry with the little boy, and she pushed him from one corner to the other and slapped him here and cuffed him there, until the poor child was always afraid, for when he came home from school there was nowhere he could find any peace.

One day the woman had gone upstairs to her room, when her little daughter came up too, and said, “Mother, give me an apple.”

“Yes, my child,” said the woman, and gave her a beautiful apple out of the chest. The chest had a large heavy lid with a large sharp iron lock.

“Mother,” said the little daughter, “is brother not to have one too?”

This made the woman angry, but she said, “Yes, when he comes home from school.”

When from the window she saw him coming, it was as though the Evil One came over her, and she grabbed the apple and took it away from her daughter, saying, “You shall not have one before your brother.”

She threw the apple into the chest, and shut it. Then the little boy came in the door, and the Evil One made her say to him kindly, “My son, do you want an apple?” And she looked at him fiercely.

“Mother,” said the little boy, “how angry you look. Yes, give me an apple.”

Then it seemed to her as if she had to persuade him. “Come with me,” she said, opening the lid of the chest. “Take out an apple for yourself.” And while the little boy was leaning over, the Evil One prompted her, and crash! she slammed down the lid, and his head flew off, falling among the red apples.

Then fear overcame her, and she thought, “Maybe I can get out of this.” So she went upstairs to her room to her chest of drawers, and took a white scarf out of the top drawer, and set the head on the neck again, tying the scarf around it so that nothing could be seen. Then she set him on a chair in front of the door and put the apple in his hand.

After this Marlene came into the kitchen to her mother, who was standing by the fire with a pot of hot water before her which she was stirring around and around.

“Mother,” said Marlene, “brother is sitting at the door, and he looks totally white and has an apple in his hand. I asked him to give me the apple, but he did not answer me, and I was very frightened.”

“Go back to him,” said her mother, “and if he will not answer you, then box his ears.”

So Marlene went to him and said, “Brother, give me the apple.” But he was silent, so she gave him one on the ear, and his head fell off. Marlene was terrified, and began crying and screaming, and ran to her mother, and said, “Oh, mother, I have knocked my brother’s head off,” and she cried and cried and could not be comforted.

“Marlene,” said the mother, “what have you done? Be quiet and don’t let anyone know about it. It cannot be helped now. We will cook him into stew.”

Then the mother took the little boy and chopped him in pieces, put him into the pot, and cooked him into stew. But Marlene stood by crying and crying, and all her tears fell into the pot, and they did not need any salt.

Then the father came home, and sat down at the table and said, “Where is my son?” And the mother served up a large, large dish of stew, and Marlene cried and could not stop.

Then the father said again, “Where is my son?”

“Oh,” said the mother, “he has gone across the country to his mother’s great uncle. He will stay there awhile.”

“What is he doing there? He did not even say good-bye to me.”

“Oh, he wanted to go, and asked me if he could stay six weeks. He will be well taken care of there.”

“Oh,” said the man, “I am unhappy. It isn’t right. He should have said good-bye to me.” With that he began to eat, saying, “Marlene, why are you crying? Your brother will certainly come back.”

Then he said, “Wife, this food is delicious. Give me some more.” And the more he ate the more he wanted, and he said, “Give me some more. You two shall have none of it. It seems to me as if it were all mine.” And he ate and ate, throwing all the bones under the table, until he had finished it all.

Marlene went to her chest of drawers, took her best silk scarf from the bottom drawer, and gathered all the bones from beneath the table and tied them up in her silk scarf, then carried them outside the door, crying tears of blood.

She laid them down beneath the juniper tree on the green grass, and after she had put them there, she suddenly felt better and did not cry anymore.

Then the juniper tree began to move. The branches moved apart, then moved together again, just as if someone were rejoicing and clapping his hands.

At the same time a mist seemed to rise from the tree, and in the center of this mist it burned like a fire, and a beautiful bird flew out of the fire singing magnificently, and it flew high into the air, and when it was gone, the juniper tree was just as it had been before, and the cloth with the bones was no longer there.

Marlene, however, was as happy and contented as if her brother were still alive. And she went merrily into the house, sat down at the table, and ate.

Then the bird flew away and lit on a goldsmith’s house, and began to sing:

My mother, she killed me,

My father, he ate me,

My sister Marlene,

Gathered all my bones,

Tied them in a silken scarf,

Laid them beneath the juniper tree,

Tweet, tweet, what a beautiful bird am I.

The goldsmith was sitting in his workshop making a golden chain, when he heard the bird singing on his roof. The song seemed very beautiful to him. He stood up, but as he crossed the threshold he lost one of his slippers.

However, he went right up the middle of the street with only one slipper and one sock on. He had his leather apron on, and in one hand he had a golden chain and in the other his tongs. The sun was shining brightly on the street.

He walked onward, then stood still and said to the bird, “Bird,” he said, “how beautifully you can sing. Sing that piece again for me.”

“No,” said the bird, “I do not sing twice for nothing. Give me the golden chain, and then I will sing it again for you.”

The goldsmith said, “Here is the golden chain for you. Now sing that song again for me.” Then the bird came and took the golden chain in his right claw, and went and sat in front of the goldsmith, and sang:

My mother, she killed me,

My father, he ate me,

My sister Marlene,

Gathered all my bones,

Tied them in a silken scarf,

Laid them beneath the juniper tree,

Tweet, tweet, what a beautiful bird am I.

Then the bird flew away to a shoemaker, and lit on his roof and sang:

My mother, she killed me,

My father, he ate me,

My sister Marlene,

Gathered all my bones,

Tied them in a silken scarf,

Laid them beneath the juniper tree,

Tweet, tweet, what a beautiful bird am I.

Hearing this, the shoemaker ran out of doors in his shirtsleeves, and looked up at his roof, and had to hold his hand in front of his eyes to keep the sun from blinding him. “Bird,” said he, “how beautifully you can sing.”

Then he called in at his door, “Wife, come outside. There is a bird here. Look at this bird. He certainly can sing.”

Then he called his daughter and her children, and the journeyman, and the apprentice, and the maid, and they all came out into the street and looked at the bird and saw how beautiful he was, and what fine red and green feathers he had, and how his neck was like pure gold, and how his eyes shone like stars in his head.

“Bird,” said the shoemaker, “now sing that song again for me.”

“No,” said the bird, “I do not sing twice for nothing. You must give me something.”

“Wife,” said the man, “go into the shop. There is a pair of red shoes on the top shelf. Bring them down.” Then the wife went and brought the shoes.

“There, bird,” said the man, “now sing that piece again for me.” Then the bird came and took the shoes in his left claw, and flew back to the roof, and sang:

My mother, she killed me,

My father, he ate me,

My sister Marlene,

Gathered all my bones,

Tied them in a silken scarf,

Laid them beneath the juniper tree,

Tweet, tweet, what a beautiful bird am I.

When he had finished his song he flew away. In his right claw he had the chain and in his left one the shoes. He flew far away to a mill, and the mill went clickety-clack, clickety-clack, clickety-clack. In the mill sat twenty miller’s apprentices cutting a stone, and chiseling chip-chop, chip-chop, chip-chop. And the mill went clickety-clack, clickety-clack, clickety-clack.

Then the bird went and sat on a linden tree which stood in front of the mill, and sang:

My mother, she killed me,

Then one of them stopped working.

My father, he ate me,

Then two more stopped working and listened,

My sister Marlene,

Then four more stopped,

Gathered all my bones,

Tied them in a silken scarf,

Now only eight only were chiseling,

Laid them beneath

Now only five,

the juniper tree,

Now only one,

Tweet, tweet, what a beautiful bird am I.

Then the last one stopped also, and heard the last words. “Bird,” said he, “how beautifully you sing. Let me hear that too. Sing it once more for me.”

“No,” said the bird, “I do not sing twice for nothing. Give me the millstone, and then I will sing it again.”

“Yes,” he said, “if it belonged only to me, you should have it.”

“Yes,” said the others, “if he sings again he can have it.”

Then the bird came down, and the twenty millers took a beam and lifted the stone up. Yo-heave-ho! Yo-heave-ho! Yo-heave-ho!

The bird stuck his neck through the hole and put the stone on as if it were a collar, then flew to the tree again, and sang:

My mother, she killed me,

My father, he ate me,

My sister Marlene,

Gathered all my bones,

Tied them in a silken scarf,

Laid them beneath the juniper tree,

Tweet, tweet, what a beautiful bird am I.

When he was finished singing, he spread his wings, and in his right claw he had the chain, and in his left one the shoes, and around his neck the millstone. He flew far away to his father’s house.

In the room the father, the mother, and Marlene were sitting at the table.

The father said, “I feel so contented. I am so happy.”

“Not I,” said the mother, “I feel uneasy, just as if a bad storm were coming.”

But Marlene just sat and cried and cried.

Then the bird flew up, and as it seated itself on the roof, the father said, “Oh, I feel so truly happy, and the sun is shining so beautifully outside. I feel as if I were about to see some old acquaintance again.”

“Not I,” said the woman, “I am so afraid that my teeth are chattering, and I feel like I have fire in my veins.” And she tore open her bodice even more. Marlene sat in a corner crying. She held a handkerchief before her eyes and cried until it was wet clear through.

Then the bird seated itself on the juniper tree, and sang:

My mother, she killed me,

The mother stopped her ears and shut her eyes, not wanting to see or hear, but there was a roaring in her ears like the fiercest storm, and her eyes burned and flashed like lightning.

My father, he ate me,

“Oh, mother,” said the man, “that is a beautiful bird. He is singing so splendidly, and the sun is shining so warmly, and it smells like pure cinnamon.”

My sister Marlene,

Then Marlene laid her head on her knees and cried and cried, but the man said, “I am going out. I must see the bird up close.”

“Oh, don’t go,” said the woman, “I feel as if the whole house were shaking and on fire.”

But the man went out and looked at the bird.

Gathered all my bones,

Tied them in a silken scarf,

Laid them beneath the juniper tree,

Tweet, tweet, what a beautiful bird am I.

With this the bird dropped the golden chain, and it fell right around the man’s neck, so exactly around it that it fit beautifully. Then the man went in and said, “Just look what a beautiful bird that is, and what a beautiful golden chain he has given me, and how nice it looks.”

But the woman was terrified. She fell down on the floor in the room, and her cap fell off her head. Then the bird sang once more:

My mother killed me.

“I wish I were a thousand fathoms beneath the earth, so I would not have to hear that!”

My father, he ate me,

Then the woman fell down as if she were dead.

My sister Marlene,

“Oh,” said Marlene, “I too will go out and see if the bird will give me something.” Then she went out.

Gathered all my bones,

Tied them in a silken scarf,

He threw the shoes down to her.

Laid them beneath the juniper tree,

Tweet, tweet, what a beautiful bird am I.

Then she was contented and happy. She put on the new red shoes and danced and leaped into the house. “Oh,” she said, “I was so sad when I went out and now I am so contented. That is a splendid bird, he has given me a pair of red shoes.”

“No,” said the woman, jumping to her feet and with her hair standing up like flames of fire, “I feel as if the world were coming to an end. I too, will go out and see if it makes me feel better.”

And as she went out the door, crash! the bird threw the millstone on her head, and it crushed her to death.

The father and Marlene heard it and went out. Smoke, flames, and fire were rising from the place, and when that was over, the little brother was standing there, and he took his father and Marlene by the hand, and all three were very happy, and they went into the house, sat down at the table, and ate.

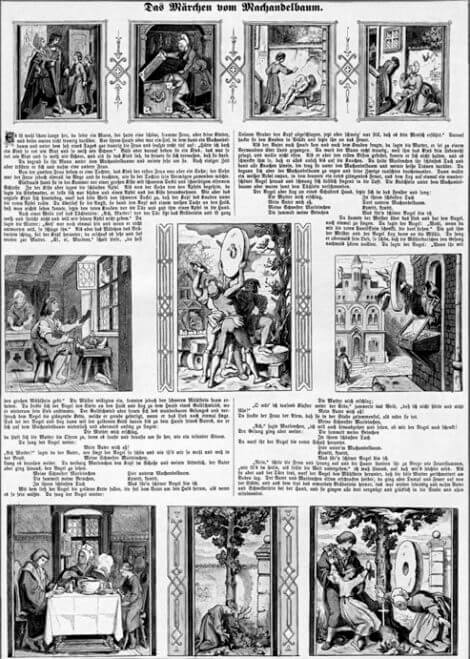

Von dem Machandelboom

Von dem Machandelboom

Ein Märchen der Brüder Grimm

Das ist nun lange her, wohl an die zweitausend Jahre, da war einmal ein reicher Mann, der hatte eine schöne fromme Frau, und sie hatten sich beide sehr lieb, hatten aber keine Kinder. Sie wünschten sich aber sehr welche, und die Frau betete darum soviel Tag und Nacht; aber sie kriegten und kriegten keine. Vor ihrem Hause war ein Hof, darauf stand ein Machandelbaum. Unter dem stand die Frau einstmals im Winter und schälte sich einen Apfel, und als sie sich den Apfel so schälte, da schnitt sie sich in den Finger, und das Blut fiel in den Schnee.

“Ach,” sagte die Frau und seufzte so recht tief auf, und sah das Blut vor sich an, und war so recht wehmütig: “Hätte ich doch ein Kind, so rot wie Blut und so weiss wie Schnee.” Und als sie das sagte, da wurde ihr so recht fröhlich zumute: Ihr war so recht, als sollte es etwas werden. Dann ging sie nach Hause, und es ging ein Monat hin, da verging der Schnee; und nach zwei Monaten, da wurde alles grün; nach drei Monaten, da kamen die Blumen aus der Erde; und nach vier Monaten, da schossen alle Bäume ins Holz, und die grünen Zweige waren alle miteinander verwachsen. Da sangen die Vöglein, dass der ganze Wald erschallte, und die Blüten fielen von den Bäumen, da war der fünfte Monat vergangen, und sie stand immer unter dem Machandelbaum, der roch so schön. Da sprang ihr das Herz vor Freude, und sie fiel auf die Knie und konnte sich gar nicht lassen. Und als der sechste Monat vorbei war, da wurden die Früchte dick und stark, und sie wurde ganz still. Und im siebenten Monat, da griff sie nach den Machandelbeeren und ass sie so begehrlich; und da wurde sie traurig und krank. Da ging der achte Monat hin, und sie rief ihren Mann und weinte und sagte: “Wenn ich sterbe, so begrabe mich unter dem Machandelbaum.” Da wurde sie ganz getrost und freute sich, bis der neunte Monat vorbei war: da kriegte sie ein Kind so weiss wie der Schnee und so rot wie Blut, und als sie das sah, da freute sie sich so, dass sie starb.

Da begrub ihr Mann sie unter dem Machandelbaum, und er fing an, so sehr zu weinen; eine Zeitlang dauerte das, dann flossen die Tränen schon sachter, und als er noch etwas geweint hatte, da hörte er auf, und dann nahm er sich wieder eine Frau.

Mit der zweiten Frau hatte er eine Tochter; das Kind aber von der ersten Frau war ein kleiner Sohn, und war so rot wie Blut und so weiss wie Schnee. Wenn die Frau ihre Tochter so ansah, so hatte sie sie sehr lieb; aber dann sah sie den kleinen Jungen an, und das ging ihr so durchs Herz, und es dünkte sie, als stünde er ihr überall im Wege, und sie dachte dann immer, wie sie ihrer Tochter all das Vermögen zuwenden wollte, und der Böse gab es ihr ein, dass sie dem kleinen Jungen ganz gram wurde, und sie stiess ihn aus einer Ecke in die andere, und puffte ihn hier und knuffte ihn dort, so dass das arme Kind immer in Angst war. Wenn er dann aus der Schule kam, so hatte er keinen Platz, wo man ihn in Ruhe gelassen hätte.

Einmal war die Frau in die Kammer hoch gegangen; da kam die kleine Tochter auch herauf und sagte: “Mutter, gib mir einen Apfel.” – “Ja, mein Kind,” sagte die Frau und gab ihr einen schönen Apfel aus der Kiste; die Kiste aber hatte einen grossen schweren Deckel mit einem grossen scharfen eisernen Schloss. “Mutter,” sagte die kleine Tochter, “soll der Bruder nicht auch einen haben?”

Das verdross die Frau, doch sagte sie: “Ja, wenn er aus der Schule kommt.” Und als sie ihn vom Fenster aus gewahr wurde, so war das gerade, als ob der Böse in sie gefahren wäre, und sie griff zu und nahm ihrer Tochter den Apfel wieder weg und sagte; “Du sollst ihn nicht eher haben als der Bruder.” Da warf sie den Apfel in die Kiste und machte die Kiste zu.

Da kam der kleine Junge in die Tür; da gab ihr der Böse ein, dass sie freundlich zu ihm sagte: “Mein Sohn, willst du einen Apfel haben?” und sah ihn so jähzornig an. “Mutter,” sagte der kleine Junge, “was siehst du so grässlich aus! Ja, gib mir einen Apfel!” –

Da war ihr, als sollte sie ihm zureden. “Komm mit mir,” sagte sie und machte den Deckel auf, “hol dir einen Apfel heraus!” Und als der kleine Junge sich hineinbückte, da riet ihr der Böse; bratsch! Schlug sie den Deckel zu, dass der Kopf flog und unter die roten Äpfel fiel.

Da überlief sie die Angst, und sie dachte: “Könnt ich das von mir bringen!” Da ging sie hinunter in ihre Stube zu ihrer Kommode und holte aus der obersten Schublade ein weisses Tuch und setzt den Kopf wieder auf den Hals und band das Halstuch so um, dass man nichts sehen konnte und setzt ihn vor die Türe auf einen Stuhl und gab ihm den Apfel in die Hand.

Darnach kam Marlenchen zu ihrer Mutter in die Küche. Die stand beim Feuer und hatte einen Topf mit heissem Wasser vor sich, den rührte sie immer um. “Mutter,” sagte Marlenchen, “der Bruder sitzt vor der Türe und sieht ganz weiss aus und hat einen Apfel in der Hand. Ich hab ihn gebeten, er soll mir den Apfel geben, aber er antwortet mir nicht; das war mir ganz unheimlich.” – “Geh noch einmal hin,” sagte die Mutter, “und wenn er dir nicht antwortet, dann gib ihm eins hinter die Ohren.”

Da ging Marlenchen hin und sagte: “Bruder, gib mir den Apfel!” Aber er schwieg still; da gab sie ihm eins hinter die Ohren. Da fiel der Kopf herunter; darüber erschrak sie und fing an zu weinen und zu schreien und lief zu ihrer Mutter und sagte: “Ach, Mutter, ich hab meinem Bruder den Kopf abgeschlagen,” und weinte und weinte und wollte sich nicht zufrieden geben.

“Marlenchen,” sagte die Mutter, “was hast du getan! Aber schweig nur still, dass es kein Mensch merkt; das ist nun doch nicht zu ändern, wir wollen ihn in Sauer kochen.”

Da nahm die Mutter den kleinen Jungen und hackte ihn in Stücke, tat sie in den Topf und kochte ihn in Sauer. Marlenchen aber stand dabei und weinte und weinte, und die Tränen fielen alle in den Topf, und sie brauchten kein Salz.

Da kam der Vater nach Hause und setzte sich zu Tisch und sagte: “Wo ist denn mein Sohn?” Da trug die Mutter eine grosse, grosse Schüssel mit Schwarzsauer auf, und Marlenchen weinte und konnte sich nicht halten. Da sagte der Vater wieder: “Wo ist denn mein Sohn?” – “Ach,” sagte die Mutter, “er ist über Land gegangen, zu den Verwandten seiner Mutter; er wollte dort eine Weile bleiben.” – “Was tut er denn dort? Er hat mir nicht mal Lebewohl gesagt!” – “

Oh, er wollte so gern hin und bat mich, ob er dort wohl sechs Wochen bleiben könnte; er ist ja gut aufgehoben dort.” – “Ach,” sagte der Mann, “mir ist so recht traurig zumute; das ist doch nicht recht, er hätte mir doch Lebewohl sagen können.” Damit fing er an zu essen und sagte: “Marlenchen, warum weinst du? Der Bruder wird schon wiederkommen.” – “Ach Frau,” sagte er dann, “was schmeckt mir das Essen schön! Gib mir mehr!” Und je mehr er ass, um so mehr wollte er haben und sagte: “Gebt mir mehr, ihr sollt nichts davon aufheben, das ist, als ob das alles mein wäre.”

Und er ass und ass, und die Knochen warf er alle unter den Tisch, bis er mit allem fertig war. Marlenchen aber ging hin zu ihrer Kommode und nahm aus der untersten Schublade ihr bestes seidenes Tuch und holte all die Beinchen und Knochen unter dem Tisch hervor und band sie in das seidene Tuch und trug sie vor die Tür und weinte blutige Tränen. Dort legte sie sie unter den Machandelbaum in das grüne Gras, und als sie sie dahin gelegt hatte, da war ihr auf einmal ganz leicht, und sie weinte nicht mehr.

Da fing der Machandelbaum an, sich zu bewegen, und die zweige gingen immer so voneinander und zueinander, so recht, wie wenn sich einer von Herzen freut und die Hände zusammenschlägt. Dabei ging ein Nebel von dem Baum aus, und mitten in dem Nebel, da brannte es wie Feuer, und aus dem Feuer flog so ein schöner Vogel heraus, der sang so herrlich und flog hoch in die Luft, und als er weg war, da war der Machandelbaum wie er vorher gewesen war, und das Tuch mit den Knochen war weg. Marlenchen aber war so recht leicht und vergnügt zumute, so recht, als wenn ihr Bruder noch lebte. Da ging sie wieder ganz lustig nach Hause, setzte sich zu Tisch und ass. Der Vogel aber flog weg und setzte sich auf eines Goldschmieds Haus und fing an zu singen:

“Mein Mutter der mich schlacht,

mein Vater der mich ass,

mein Schwester der Marlenichen

sucht alle meine Benichen,

bindt sie in ein seiden Tuch,

legt’s unter den Machandelbaum.

Kiwitt, kiwitt, wat vör’n schöön Vagel bün ik!”

Der Goldschmied sass in seiner Werkstatt und machte eine goldene Kette; da hörte er den Vogel, der auf seinem Dach sass und sang, und das dünkte ihn so schön. Da stand er auf, und als er über die Türschwelle ging, da verlor er einen Pantoffel. Er ging aber so recht mitten auf die Strasse hin, mit nur einem Pantoffel und einer Socke; sein Schurzfell hatte er vor, und in der einen Hand hatte er die goldene Kette, und in der anderen die Zange; und die Sonne schien so hell auf die Strasse. Da stellte er sich nun hin und sah den Vogel an. “Vogel,” sagte er da, “wie schön kannst du singen! Sing mir das Stück noch mal!” – “Nein,” sagte der Vogel, “zweimal sing ich nicht umsonst. Gib mir die goldene Kette, so will ich es dir noch einmal singen.” – “Da,” sagte der Goldschmied, “hast du die goldene Kette; nun sing mir das noch einmal!” Da kam der Vogel und nahm die goldene Kette in die rechte Kralle, setzte sich vor den Goldschmied hin und sang:

“Mein Mutter der mich schlacht,

mein Vater der mich ass,

mein Schwester der Marlenichen

sucht alle meine Benichen,

bindt sie in ein seiden Tuch,

legt’s unter den Machandelbaum.

Kiwitt, kiwitt, wat vör’n schöön Vagel bün ik!”

Da flog der Vogel fort zu einem Schuster, und setzt sich auf sein Dach und sang:

“Mein Mutter der mich schlacht,

mein Vater der mich ass,

mein Schwester der Marlenichen

sucht alle meine Benichen,

bindt sie in ein seiden Tuch,

legt’s unter den Machandelbaum.

Kiwitt, kiwitt, wat vör’n schöön Vagel bün ik!”

Der Schuster hörte das und lief in Hemdsärmeln vor seine Tür und sah zu seinem Dach hinauf und musste die Hand vor die Augen halten, dass die Sonne ihn nicht blendete. “Vogel,” sagte er, “was kannst du schön singen.” Da rief er zur Tür hinein: “Frau, komm mal heraus, da ist ein Vogel; sieh doch den Vogel, der kann mal schön singen.” Dann rief er noch seine Tochter und die Kinder und die Gesellen, die Lehrjungen und die Mägde, und sie kamen alle auf die Strasse und sahen den Vogel an, wie schön er war; und er hatte so schöne rote und grüne Federn, und um den Hals war er wie lauter Gold, und die Augen blickten ihm wie Sterne im Kopf. “Vogel,” sagte der Schuster, “nun sing mir das Stück noch einmal!” – “Nein,” sagte der Vogel, “zweimal sing ich nicht umsonst, du musst mir etwas schenken.” – “Frau,” sagte der Mann, “geh auf den Boden, auf dem obersten Wandbrett, da stehen ein paar rote Schuh, die bring mal her!” Da ging die Frau hin und holte die Schuhe. “Da, Vogel,” sagte der Mann, “nun sing mir das Lied noch einmal!” Da kam der Vogel und nahm die Schuhe in die linke Kralle und flog wieder auf das Dach und sang:

“Mein Mutter der mich schlacht,

mein Vater der mich ass,

mein Schwester der Marlenichen

sucht alle meine Benichen,

bindt sie in ein seiden Tuch,

legt’s unter den Machandelbaum.

Kiwitt, kiwitt, wat vör’n schöön Vagel bün ik!”

Und als er ausgesungen hatte, da flog er weg; die Kette hatte er in der rechten und die Schuhe in der linken Kralle, und er flog weit weg, bis zu einer Mühle, und die Mühle ging: Klippe klappe, klippe klappe, klippe klappe. Und in der Mühle sassen zwanzig Mühlknappen, die klopften einen Stein und hackten: Hick hack, hick hack, hick hack; und die Mühle ging klippe klappe, klippe klappe, klippe klappe. Da setzte sich der Vogel auf einen Lindenbaum, der vor der Mühle stand und sang: “Mein Mutter der mich schlacht,” da hörte einer auf; “mein Vater der mich ass,” da hörten noch zwei auf und hörten zu; “mein Schwester der Marlenichen” da hörten wieder vier auf;

“sucht alle meine Benichen, bindt sie in ein seiden Tuch,” nun hackten nur acht;

“legt’s unter,” nun nur noch fünf;

“den Machandelbaum” – nun nur noch einer;

“Kiwitt, kiwitt, wat vör’n schöön Vagel bün ik!”

Da hörte der letzte auch auf, und er hatte gerade noch den Schluss gehört. “Vogel,” sagte er, “was singst du schön! Lass mich das auch hören, sing mir das noch einmal!” – “Nein,” sagte der Vogel, “zweimal sing ich nicht umsonst; gib mir den Mühlenstein, so will ich das noch einmal singen.” –

“Ja,” sagte er, “wenn er mir allein gehörte, so solltest du ihn haben.” – “Ja,” sagten die anderen, “wenn er noch einmal singt, so soll er ihn haben.”

Da kam der Vogel heran und die Müller fassten alle zwanzig mit Bäumen an und hoben den Stein auf, “hu uh uhp, hu uh uhp, hu uh uhp!” Da steckte der Vogel den Hals durch das Loch und nahm ihn um wie einen Kragen und flog wieder auf den Baum und sang:

“Mein Mutter der mich schlacht,

mein Vater der mich ass,

mein Schwester der Marlenichen

sucht alle meine Benichen,

bindt sie in ein seiden Tuch,

legt’s unter den Machandelbaum.

Kiwitt, kiwitt, wat vör’n schöön Vagel bün ik!”

Und als er das ausgesungen hatte, da tat er die Flügel auseinander und hatte in der echten Kralle die Kette und in der linken die Schuhe und um den Hals den Mühlenstein, und flog weit weg zu seines Vaters Haus.

In der Stube sass der Vater, die Mutter und Marlenchen bei Tisch, und der Vater sagte: “Ach, was wird mir so leicht, mir ist so recht gut zumute.” –

“Nein,” sagte die Mutter, “mir ist so recht angst, so recht, als wenn ein schweres Gewitter käme.” Marlenchen aber sass und weinte und weinte.

Da kam der Vogel angeflogen, und als er sich auf das Dach setzte, da sagte der Vater: “Ach, mir ist so recht freudig, und die Sonne scheint so schön, mir ist ganz, als sollte ich einen alten Bekannten wiedersehen!” –

“Nein,” sagte die Frau, “mir ist angst, die Zähne klappern mir und mir ist, als hätte ich Feuer in den Adern.” Und sie riss sich ihr Kleid auf, um Luft zu kriegen. Aber Marlenchen sass in der Ecke und weinte, und hatte ihre Schürze vor den Augen und weinte die Schürze ganz und gar nass. Da setzte sich der Vogel auf den Machandelbaum und sang: “Meine Mutter die mich schlacht” – Da hielt sich die Mutter die Ohren zu und kniff die Augen zu und wollte nicht sehen und hören, aber es brauste ihr in den Ohren wie der allerstärkste Sturm und die Augen brannten und zuckten ihr wie Blitze. “Mein Vater der mich ass” – “Ach Mutter,” sagte der Mann, “da ist ein schöner Vogel, der singt so herrlich und die Sonne scheint so warm, und das riecht wie lauter Zinnamom.” (Zimt) “Mein Schwester der Marlenichen” – Da legte Marlenchen den Kopf auf die Knie und weinte in einem fort.

Der Mann aber sagte: “Ich gehe hinaus; ich muss den Vogel in der Nähe sehen.” – “Ach, geh nicht,” sagte die Frau,

“mir ist, als bebte das ganze Haus und stünde in Flammen.” Aber der Mann ging hinaus und sah sich den Vogel an – “sucht alle meine Benichen, bindt sie in ein seiden Tuch, legt’s unter den Machandelbaum. Kiwitt, kiwitt, wat vör’n schöön Vagel bün ik!”

Damit liess der Vogel die goldene Kette fallen, und sie fiel dem Mann gerade um den Hals, so richtig herum, dass sie ihm ganz wunderschön passte. Da ging er herein und sagte:

“Sieh, was ist das für ein schöner Vogel, hat mir eine so schöne goldene Kette geschenkt und sieht so schön aus.” Der Frau aber war so angst, dass sie lang in die Stube hinfiel und ihr die Mütze vom Kopf fiel. Da sang der Vogel wieder: “Mein Mutter der mich schlacht” – “Ach, dass ich tausend Klafter unter der Erde wäre, dass ich das nicht zu hören brauchte!” – “Mein Vater der mich ass” –

Da fiel die Frau wie tot nieder. “Mein Schwester der Marlenichen” – “Ach,” sagte Marlenchen, “ich will doch auch hinausgehen und sehn, ob mir der Vogel etwas schenkt?” Da ging sie hinaus. “Sucht alle meine Benichen, bindt sie in ein seiden Tuch” – Da warf er ihr die Schuhe herunter.

“Legt’s unter den Machandelbaum. Kiwitt, kiwitt, wat vör’n schöön Vagel bün ik!”

Da war ihr so leicht und fröhlich. Sie zog sich die neuen roten Schuhe an und tanzte und sprang herein. “Ach,” sagte sie, “mir war so traurig, als ich hinausging, und nun ist mir so leicht. Das ist mal ein herrlicher Vogel, hat mir ein Paar rote Schuhe geschenkt!” – “Nein,” sagte die Frau und sprang auf, und die Haare standen ihr zu Berg wie Feuerflammen, “mir ist, als sollte die Welt untergehen; ich will auch hinaus, damit mir leichter wird.”

Und als sie aus der Tür kam, bratsch! Warf ihr der Vogel den Mühlstein auf den Kopf, dass sie ganz zerquetscht wurde. Der Vater und Marlenchen hörten das und gingen hinaus. Da ging ein Dampf und Flammen und Feuer aus von der Stätte, und als das vorbei war, da stand der kleine Bruder da, und er nahm seinen Vater und Marlenchen bei der Hand und waren alle drei so recht vergnügt und gingen ins Haus, setzten sich an den Tisch und assen.

NOTE:

The rhymes that the bird sings show great consistency, particularly across Western Europe.

The juniper was chosen because it was believed to have a certain magical power.

That the collected bones of a dead person make its resurrection possible was a popular belief from northernmost Europe to the Orient.

The oldest evidence of the fairy tale is probably the allusions made by Goethe in Faust (1774). The thought itself, however, is already encountered in the Odyssey, where it is said that Itylus was killed by mistake by his mother, who, having been transformed into a nightingale, laments the death of her son.

Sophocles (400 B.C.) has a different version. He says that Itylus, under the name of Itys, was killed by his mother in revenge for her husband’s infidelity. Itys then was roasted and given to the husband to eat.

The mother was therefore turned into a swallow. It should be noted that in both cases it is the mother and not the son who turns into a bird.

Variants of the birdsong

Germany:

„mei Moddr hot mi toudt g’schlagn,

mei Schwestr hot mi hinausgetragn,

mei Vaddr hot mi gesse:

i bin doch noh do!

Kiwitt, Kiwitt.“

Hessen:

„meine Mutter kocht mich,

mein Vater aß mich,

Schwesterchen unterm Tische saß,

die Knöchlein all all auflas,

warf sie übern Birnbaum hinaus,

da ward ein Vögelein daraus,

das singet Tag und Nacht.“

Schwaben:

„zwick! zwick!

ein schönes Vöglein bin ich.

Mein Mutter hat mich kocht,

mein Vater hat mich geßt.“

Goethes Faust I:

„meine Mutter die Hur,

die mich umgebracht hat,

mein Vater der Schelm,

der mich gegessen hat,

mein Schwesterlein klein

hub auf die Bein,

an einem kühlen Ort,

da ward ich schönes Waldvögelein,

fliege fort, fliege fort!“

South France:

ma marâtre pique pâtre

m’a fait bouillir et rebouillir.

mon père le laboureur

m’a mangé et rongé.

ma jeune soeur la Lisette

m’a pleuré et soupiré:

sous un arbre m’a enterré,

riou, tsiou, tsiou!

je suis encore en vie.

From a Scottish tale:

„pew wew, pew wew, (pipi, wiwi,)

my minny me slew”

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- D. L. Ashliman’s folktexts, a library of folktales, folklore, fairy tales, and mythology.

- The Grimm Brothers’ Children’s and Household Tales (Grimms’ Fairy Tales).

- The Grimm Brothers’ Home Page.

- The Juniper Tree (fairy tale). Wikipedia.

- The Juniper Tree. Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm.

- Von dem Machandelbaum.

- Von dem Machandelboom Märchen. Ein Märchen der Brüder Grimm.

- Von dem Machandelboom. Plattdeutsche Version. Jacob und Wilhelm Grimm. Kinder- und Hausmärchen. 1812.