Discover legends, myths and folklore of the coconut palm tree and its use in traditional Indian culture. Oral literature abounds with proverbs, fables, myths, and legends associated with this special nut and have been associated with the origin of the plant in India, Malaysia, Hawaii, Myanmar, Maldives, Philippines, Indonesia, and Polynesian countries.

In this Article

Malesia, a bio-geographical region that includes Southeast Asia (India), Indonesia, Australia, New Guinea, and several Pacific Island groups is thought to be the home of the coconut palm.

The tree has been recorded in archaeological excavations and epigraphic inscriptions, in Sanskrit scriptures of religious, agricultural, and Ayurvedic importance, and in historical records as well as travelogues of visitors from China, Arabia, and Italy.

Reference on coconut (kanbar) appeared as early as 1030 AD in Al-Birhuni. Ibn Batutta (1333) mentions that

“It makes an excellent honey and the merchants of India, Yemen, and China buy it and take it to their own countries where they manufacture sweetmeats from it.”

Coconuts made a strong impression on Venetian explorer Marco Polo, 1254 to 1324 C.E., when he encountered them in Sumatra, India, and the Nicobar Islands, and called them “Pharaoh’s nut”. The reference to the Egyptian ruler indicated Polo was aware that during the 6th century Arab merchants brought coconuts back to Egypt probably from East Africa where the nuts were flourishing.

TREE OF LIFE

In India, it is appropriately called ‘Kalpavriksha’ a mythological tree supposed to grant all desires or – “the tree that provides all the necessities of life”.

In Sanskrit literature the miraculous powers of this tree are described in great detail. It can offer to its devotees health, wealth, male progeny, and prosperity. It was a product of the churning of the ocean by gods and demons and ultimately it was taken by the former to heaven and planted in Indra’s garden.

It is “Pokok seribu guna” (the tree of a thousand uses) to Malays, and “Tree of life” or “Tree of heaven” for a Filipino, “Tree of abundance” or “Three generations tree” to an Indonesian. The very names are reflective of its uses essentially in everyday life of people in the tropics.

ETYMOLOGY: Coconut

The term coconut refers to the seed or the fruit of the coconut palm (Cocos nucifera) 🥥.

‘Nucifera’ means ‘nut bearing’- Latin.

The Sanskrit term narikela for coconut is believed to be derived from two words of South Asian origin, niyor for oil and kolai for nut.

The Tamil word ‘nai’ is used for a semisolid greasy fat and appears to be related with words like ngai and niu used for coconut oil in Polynesia and Nicobar islands.

The root for the coconut in Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, and Kannada languages is ‘ten’, which means south, and tenaki, the nut fruit belonging to the south.

Likewise tennaimaram-tengimara would be the tree that belongs to the south. In Sri Lanka names for coconut are derived from ten again directing towards south.

The local names for coconut in Polynesia, Melanesia (niu), the Philippines, and Guam (niyog) are derived from the Malay word nyiur or nyior.

This fact is often cited as evidence that the species originated in the Malay-Indonesian region.

Amarkosha (500–800 AD) records synonyms of coconut and refers as nariker, narikel, narikela, and langalin.

The name coco, came from Portuguese explorers, the sailors of Vasco da Gama in India, who first brought them to Europe. The coconut shell reminded them of a ghost or witch in Portuguese folklore called coco (also coca). Portuguese and Spanish authors of the 16th century agree in identifying the word with Portuguese and Spanish coco “grinning face, grin, grimace”, also “bugbear, scarecrow”, cognate with cocar “to grin, make a grimace”.

The English word ‘coconut’ might derive from the Spanish and Portuguese word ‘coco’. The spelling ‘cocoanut’ is an old fashioned form of the word coconut.

![Cocos nucifera L. [as ténga]. 1678. Rheede tot Drakestein, H.A. van, Hortus Indicus Malabaricus, vol. 1: t. 4. Illustration contributed by the Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, U.S.A.](https://earthstoriez.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Hortus_Malabaricus_Thenga-1024x813.jpg)

MYTHS On the origin of the coconut palm

On the origin of the coconut

Indian mythology credits the creation of palm with its crown of leafy fronds to the sage Vishwamitra, to prop up his friend King Trishanku when the latter was literally thrown out of heaven by Indra for his misdeeds:

Rishi Viswamitra practiced severe austerities for a long time and in the end acquired super-human powers. To prove his powers, he decided to send king Tri-sanku to heaven in his earthly mortal body. King Tri-sanku had been exiled from his kingdom by his father for the seduction of the wife of a citizen. During the period of exile, there was a severe famine and Tri-sanku looked after the wife and children of Viswamitra while the latter was away.

Since Tri-sanku desired to reach heaven in his mortal body, Viswamitra re payed him for looking after his family, by fulfilling his desire and raised him to heaven in his mortal body in spite of strong opposition from sages and gods.

But when king Tri-sanku reached Indra’s swarag in his mortal body, Indra was furious,

“How can a mortal reside in my domain in his mortal body? Only souls are permitted”.

Feeling annoyed at the audacity of Rushi Viswamitra, he hurled the body of the king out of the heavens. When Sage Viswamitra saw this happen, he was angry, his effort was for nothing. For the king’s body to come back to earth would not only have meant an insult but also the acceptance of defeat at the hands of Indra.

So Viswamitra used his magical powers again and stopped the king from falling on the ground. This resulted in king Tri-sanku being suspended in the air. To support him, Viswamitra put a pole under him. As time passed, the pole became the coconut palm which is as straight and unbranched as the pole which Sage Viswamitra had taken to stop the further fall of the king.

Tri-sanku’s own head became its fruit, with his beard/hair as the coconut’s fiber, and his “eyes” seen if the fiber is removed.

Variant: Sage Vishwamitra created the coconut

According to Hindu mythology, the coconut was created by Sage Vishwamitra to prop up King Satyavrata who was attempting to gain entry into swargaloka (heaven) as a mortal but was thrown out by the Gods. Satyavrata was a famous king of the solar dynasty. He was a pious ruler and was greatly religious. Satyavrata had only one desire. He wished ascend to swargaloka with his mortal body intact.

Once while Vishwamitra was away performing tapsya a great drought swept the land. Satyavrata saved Vishwamitra’s family by giving them food. In gratitude, Vishwamitra agreed to help the king achieve his only desire. He started a yajna (sacrifice to the Gods) and with the powers of his prayers, Vishwamitra made Satyavrata ascend towards the sky.

As he neared the gates of heaven, Indra – the king of the God pushed the king back to earth. As Satyavrata fell he cried out to Vishwamitra, who cast a spell to stop him mid-air. Enraged Vishwamitra declared his intention to redesign the cosmos and create a heaven for Satyavrata.

Peace was restored and a compromise was reached. The Gods allowed Satyavrata to stay mid-air. However, the sage realized that Satyavrata would fall back to ground once the spell weakened.

So, he held him with a long pole. In time this pole became the trunk of the coconut tree and Satyavrata’s head became the fruit. Since, Satyavrata was suspended between space and earth; he got the epithet Trishanku ‘one who is neither here nor there’

On how the coconut got its face

The people of Kerala, have an interesting folktale that explains how the coconut tree came to be, and how the coconut got its face.

There was once a young fisherman who was unable to catch a single fish. He tried every way he knew, but none of them succeeded. The young man not only became poorer and hungrier, but also became the laughing stock of the village. This filled him with despair, and he decided to learn some magic that would help him to catch fish.

So, he went to a famous magician who taught him how to remove his head from his body. Soon the young man started going to the beach late in the evenings when all the other fishermen had returned to their homes with their daily catch. Then he would hide behind some rocks, take his head off from his body, and dive into the water.

The fish, amazed at the sight of a headless man floating in the sea, would swarm around him curiously. Some of them would enter the man’s body through his neck. The man would then swim ashore, take the fish out, and replace his head. Then he would proudly go back to his village and show the villagers all the fish that he had caught.

After a few days, the villagers began to wonder how the young man was able to catch so many fish every day without using fishing nets or rods.

One day, a curious little boy followed him to the beach and watched as he pulled off his head and dived into the water. The little boy quickly ran forward, picked up the man’s head, and threw it into a bush. When the man came out of the water, he could not find his head.

He searched for it frantically, but could not find it. Then, because his magic was running out, he threw himself back into the sea, and became a fish.

The curious little boy brought all the villagers to the beach show them the man’s amazing head. But when they got to the bush where he had thrown the man’s head, they found that it had already grown into a tall and slender palm with nuts on it.

Each nut had the man’s face on it. And, that is how the coconut tree was created.

©Santhini Govindan

In Vadakurungaduthurai, Lord Kulavanangeesar is believed to have taken the form of a coconut tree to help quench the thirst of a pregnant woman.

RITUALS & CEREMONIES:

There is no reference on the coconut in the Vedas; however, several references occur in post- Vedic works as the epic of Mahabharata (3000 BC), Ramayana (5114 BC), Puranas (350 to 1000 CE), and Buddhist stories of Jataka (300 BC and 400 CE). Other sources of information on the tree include Ayurvedic and agricultural treatises, historical accounts, travelogues, and Sanskrit literature. The Coconut is mentioned in the 2nd –1st century BC in the Mahawamsa, the historical chronicle of Sri Lanka.

Sriphala

Thus the coconut palm has a special significance as is evident from the epithet Sriphala meaning God’s fruit. In itself it is an independent object of worship so much so in Gujarat, Kanara, and Mysore it represents the house spirit, and is worshiped as a family God.

The coconut now to be found in every Indian ceremony and ritual was rather poorly known in many parts of India before sixth century BC.

Later, during times of Agni Purana (900–800 BC.) and Brahma Purana the fruit became a requirement in religious rites. It was probably in the earlier part of this period that the coconut milk began to be used for the sacred bath of deities in temples.

Offering

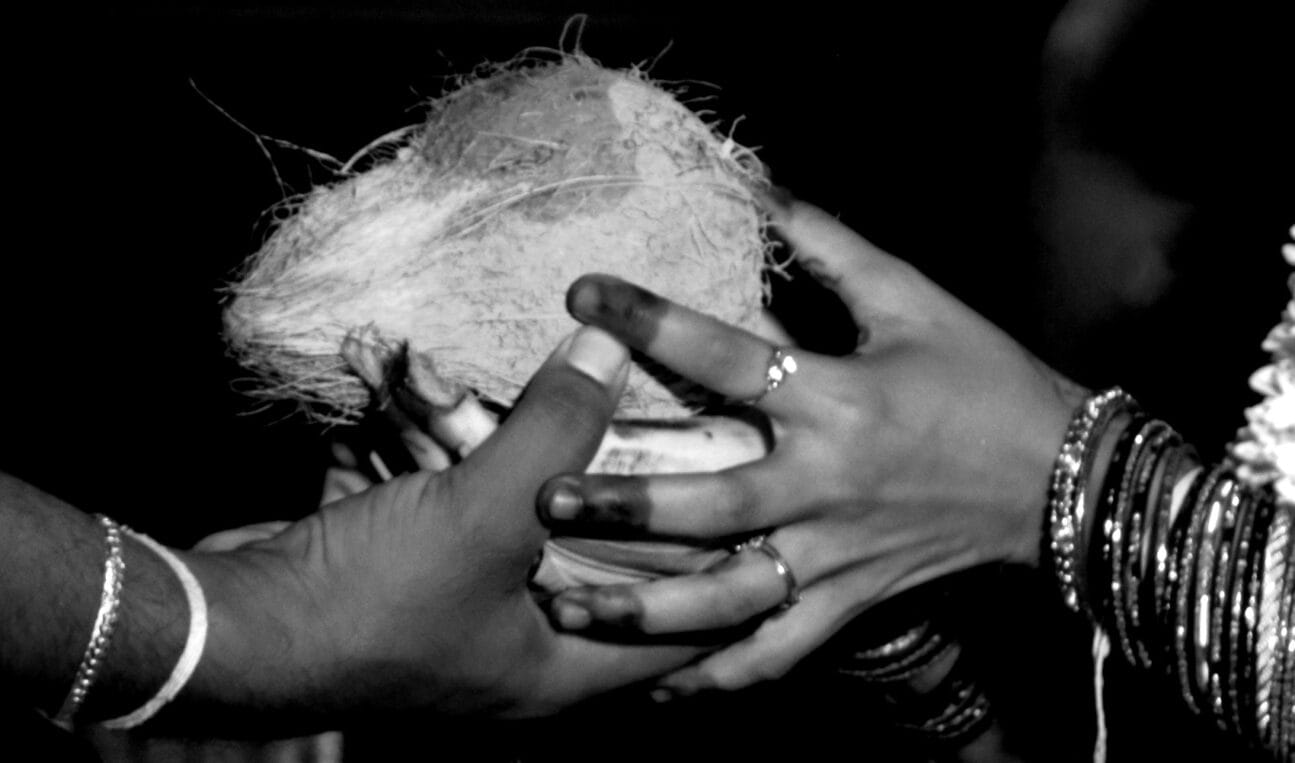

The coconut is used in rites de passage; rituals; in family, social, and religious ceremonies; and is associated with the fertility, folk culture, taboos, totems, and beliefs. Even in areas where the coconut palm does not grow, no puja or offering ceremony is complete till a coconut is offered.

The coconut is one of the most common offerings in temples; it is broken and placed before the Gods and later distributed as prasad (a devotional offering made to a god, typically consisting of food that is later shared among devotees). In South Indian temples, the priests will not accept the offerings of a devotee, if it does not contain a coconut.

The outer shell of coconut is the Ahamkara or ego, which one has to break. Once the ego is shed the mind will be as pure as the white tender coconut inside. The Bhavaavesha or Bhakthi (attachment, fondness for, devotion to, trust, homage, worship, piety, faith, or love), will pour like the sweet water in it.

The 3 eyes on the top they explain as Past, Present and Future, or as the three guna: Satwa, Raja and Tama. The three qualities are:

- Sattva is the quality of balance, harmony, goodness, purity, universalizing, holistic, constructive, creative, building, positive attitude, luminous, serenity, being-ness, peaceful, virtuous.

- Rajas is the quality of passion, activity, neither good nor bad and sometimes either, self-centeredness, egoistic, individualizing, driven, moving, dynamic.

- Tamas is the quality of imbalance, disorder, chaos, anxiety, impure, destructive, delusion, negative, dull or inactive, apathy, inertia or lethargy, violent, vicious, ignorant.

In Indian philosophy, no one and nothing is either purely sattvik or purely rajasik or purely tamasik. One’s nature and behavior is a complex interplay of all of these, with each guna in varying degrees.

A whole green coconut with stalk is an essential item in Hindu religious ceremonies. In wedding and other ceremonies green coconut is placed on earthen pitch with water in front of the pandal, while a dried coconut is used in several social and religious ceremonies; a de- husked dry coconut is offered as a symbol of human head during Bhadra Kali Puja.

The Rishis and animal sacrifice

According to a myth, all the seers or Rishis used to sacrifice a goat in order to ward off evil forces during their religious rituals. As time passed, the practice of animal sacrifice became obsolete and religious rituals became peaceful and non-violent.

Th idea of Ahimsa – ‘not to injure’ and ‘compassion’ became a key virtue in Indian religion. Today “Cause no injury, do no harm,” applies to all living beings—including all animals.

The Kols of Madhya Pradesh universally offer coconut as it represents the human skull. They offer coconut to Goddesses and Gods such as Kalimai, Kheramai (most frequently worshiped by Kols), Maridevi (Goddess of epidemics), Shardamai (chief of pantheons), Baghdeo, and Hardul Baba.

In other tantric practices, coconuts are used as substitutes for human skulls. The coconut replaced the sacrifice and ever since, the coconut, called Shrifal or fruit of lustre, became an ever present motif in India’s cultural life.

The coconut and the goddesses and gods

BHAGAVATI

In Kerala, Goddess Bhagavati is believed to be the soul of the coconut tree. One of the Goddess’s common epithets is Kurumba which means ‘tender coconut’.

At the Kottankulangara Devi Temple for the festival, the devotees dress in female attire. The cross-dressing is part of traditional ritual festivities and at night they hold traditional lamps and walk in procession to the temple to the accompaniment of an orchestra, to seek the blessings of the goddess. Bahagvathy can be used to refer to Durga, Kannaki, Parvati, Saraswati, Lakshmi, or Kali.

According to the legend, a group of cow-herders wanted to eat a coconut in a grove. When they hit the coconut on a stone (intending to remove the husk), they found drops of blood dripping from the stone. They explained the phenomena to the elders. The astrologer suggested that the stone contained supernatural powers and poojas should be started immediately after constructing a temple. The elders and cow-herders constructed a temporary temple using poles, leaves and tender leaves of the coconut palm. The cow-herders wearing female attire, offered poojas in the temple. Till today worshiper wear women clothes on special ceremonies at the temple.

Another temple, the Chottanikkara Bhagawathy Temple, is one among the most famous temples of Kerala where mentally disturbed people come in thousands to get cured.

There are two main temples. The temple of Rajarajeswari and in a slightly lower elevation, Keezhekavu, which is consecrated to Bhadra Kali . The Rajarajeswari is worshiped as Goddess Saraswati in the morning, as Bhadra kali at noon and Durga in the night. Nearby her, is the idol of Lord Vishnu. Hence the devotees always pray to her along with her brother Lord Narayana and chant ‘Amme Narayana’.

Legend tells:

That the location of this temple was rediscovered accidentally by a grass cutter, who found that blood was oozing out of a stone which he had accidentally cut. That day, the elder Brahmin of the Yedattu house came along with some puffed rice in a coconut shell and this was offered to the Goddess for the first time.

Even today offering puffed rice in a coconut shell continues.

The ‘sthala purana’ of this temple tells that:

Once the place this temple is located was a dense forest. There lived a tribal called Kannappan, whose wife had died. Kannappan was a great devotee of Goddess Parvathy. Since he was a hunter, he used to daily sacrifice an animal to his Goddess. He had a cute little daughter who was very fond of her pet, which was a cow. Since her father used to sacrifice cows also, she kept her pet cow very near to her and looked after her well. One day Kannappan could not get any other animal to sacrifice to her Goddess, and hence he ordered his daughter to give her pet cow for that day’s sacrifice.

His daughter requested Kannappan that she be sacrificed instead of her cow.

Kannappan’s heart melted and he was a changed man. He realized that he was doing a wrong thing by practicing animal sacrifice. He and the pet cow stayed near the temple’s Bali (sacrificial) stone the entire night. In the morning, the cow herself had turned in to a stone.

That place is called ‘Pavizha malli thara’ (Place of the coral jasmine flower). People believe that the pet cow of Kannappan’s daughter was indeed Goddess Mahalakshmi. That day Lord Vishnu appeared before Kannappan and pardoned his sins and decided to be present in the temple along with the Goddess. That is how the concept of Lakshmi Narayana came to this temple.

As this myth tells, Human sacrifice used to take place in India to appease Kali. But as time passed, human sacrifice gave place to animal sacrifice and ultimately to the symbolic offering of a coconut which with its round and fibrous outer covering, resembles a human head and the two dark spots on it represent the two human eyes. For this reason it is possibly offered as a symbolic human sacrifice to mother Goddess as for Ambhabhavani.

GANESH & SHIVA

In the Temple Town Palani, before going for the worship of God Murugan, at the foothills of Palani Hills, a coconut is broken or set on fire for Lord Ganesha.

O ne day as a child when Lord Ganesha was playing he was attracted by his fathers third eye and he went to touch it. Lord Shiva stopped him and said I am going to give you a special ball to play and thus the coconut came on earth which also has 3 eyes.

That is why the coconut is very special to Lord Ganesha and offered to him in ritual and worship.

The fruit is considered also a symbol of Siva as it has three black spots and Siva is believed to have three eyes.

~ Adi. Coconut in Hindu Mythology.

On Ganesha getting the Coconut fruit from Shiva

One day as a child when Lord Ganesha was playing he was attracted by his fathers third eye and he went to touch it. Lord Shiva stopped him and said I am going to give you a special ball to play and thus the coconut came on earth which also has 3 eyes.

That is why the coconut is very special to Lord Ganesha and offered to him in ritual and worship.

The fruit is considered also a symbol of Shiva as it has three black spots and Siva is believed to have three eyes.

~ Adi. Coconut in Hindu Mythology.

BRAHMA

Legend also decrees that the coconut is the primary fruit of the earth. It is likened to the head of Brahma, the creator of the universe. Thus Brahma and the coconut are considered primary to creation:

During the great deluge Brahma prepared himself for the next creation. He put all the seeds in amrta (the elixer of immortality) and kept them together in a mud pot to the chanting of Vedic mantras.

With due ceremony, he placed a coconut with mango leaves on it and invested the same with the sacred thread. Now he placed the pot on the summit of Meru. When it came floating in the waters of the deluge, Paramesvara wished to recommence creation. Then the coconut on the pot was dislodged in the storm and fell into the water.

At once the water receded revealing the land there.

This spot is four miles north-west of Kumbhakonam. The deity here is even today called “Narikelesvara”, (“narikela” means coconut).

Then the mango leaves fell off.

The water receded there too revealing land. This is Tiruppurambayam, four miles north-west of Kumbhakonam.

“Payam” [or bayam] is “payas”, that is water, but in this context deluge. “Puram” means outside or beyond something: the name of the place [Tiruppurambayam] thus means”outside the waters of the deluge”.

Now the sacred thread (sutra) also got loosened from the pot and fell off.

The deity in the place where the sutra fell is “Sutranatha”, “sutra” meaning the “sacred thread”.

~ Pancha Dravida Brahmana Mahasabha.

SARASWATI

Coconut is also worshiped as Sarasvati, the goddess of learning. In Odisha, the learning process of children is initiated after the religious ritual called Khadichhuana held on Ganesh Chaturthi (in August/September). Children carry a painted coconut door to door, singing prayer songs of Sarasvati; they collect money and give to their teachers as a mark of respect and devotion.

In India, even governmental institutions, art and science academies and universities use the coconut as a motif in honoring scholars and researchers for their achievements in the pursuit of knowledge.

LAKSHMI

Because of the economic utility of the coconut, which perhaps makes it essential in all sacred ceremonies, the fruit is also called Sriphala or “Shri-Phal” in many scriptures. Along with coconut the bananas are also called Shri-phal. “Shri” means Laxmi/Goddess of Wealth. So Shri-Phal means the fruit of Lakshmi. The reason is that these fruits are easily available. They are abundant and they are available in all the seasons. Any house which has a few coconut and banana trees in their garden, the family of that house will never starve. They will have ample supply of food through thick and thin. Thus these fruits are worshiped and are considered the gift of Goddess Laxmi. These fruits are hence used all religious ceremonies as a mark of prosperity and gratefulness to the Gods, Lakshmi is often depicted holding a coconut.

In poetry and mythology the Kalpavriksha is compared to Lakshmi as its sister emerging from the sea.

The coconut and the people

Family rituals and ceremonies

The coconut fruit is believed to fulfill one’s desires, Kalpavriksha, it is therefore considered sacred and offered to gods. In Mysore it is worshiped as a family god.

During the naming ceremony of a child on the twelfth day after its birth, coconuts are given to all the women present. The guests also put a coconut each in the lap of the new mother with a blessing that her progeny should be healthy and prosperous.

During weddings, coconuts are exchanged by both sides and are often distributed to all guests.

In Gujarat the bride offers a coconut to the bridegroom and this coconut is preserved by him throughout his life.

The fruit is a symbol of fecundity, so the women who nurse the desire for a son, are given a coconut as prasad (gift- holy food) by the priest. In other marriage rituals, it is bestowed upon women wishing to bear children and given as memento by the life partner, as proposal of marriage, welcoming of a bride, and to ward off evil.

If a son, a brother or a husband is going on a long journey, the mother, the sister or the wife applies tilak on his forehead, wishing him well and offers him a coconut.When elders, scholars, teachers, gurus or parents are honored, a coconut and a shawl symbolize the respect shown to them.

Similarly at weddings and other auspicious occasions a coconut is placed at the pandal erected for the ceremony.

The Kalash

The Kalash is generally filled with water during rituals (preferably the water of the holy Ganga, any sacred river or clean, running water). Its top open end holds betel or mango leaves, and a red-yellow sanctified thread (kalawa or mauli) is tied around its neck.

This Kalash is placed on the pujavedi (worship dais or table) near the deities or pictures of the deity. It is placed facing the North, in the center. This positioning signifies balance; balance that one needs to achieve success in every walk of life.

Often it is topped by a coconut and kept on the sacred Vedic Swastika symbol or a Vedic Swastika is drawn on it by using wet vermilion, sandal-wood powder and turmeric.

The Kunbis of Konkan region in Maharashtra worship the coconut and preserve it in the memory of their ancestors. A folksong entitled ‘five betel leaves and nine coconuts’ are repeatedly used to invoke all ancestors.

In Deccan, in cremation in absence of dead body, head is represented by a coconut, teeth by seeds of pomegranate, and 360 leaves of Butea monosperma (palas) represent the image of the dead. Similarly in Bombay, a rite of Palasvidhi is followed in case the corpse is burnt by a low caste, death at hand of an executioner or on bed or drowned and body is not found.

An effigy of the deceased is made; twigs of palas (flame of the forest) represent the bones, a coconut or bel fruit the head, pearls or cowries as eyes, and a piece of birch bark or skin of deer as cuticle, filled with urad dal (black gram) instead of flesh and blood.

This use of the coconut is also shown in this folktale from Ramanujan, A.K., in “A flowering tree and other oral tales from India”:

LEGEND: Bride for a Dead Man

LEGEND: Bride for a Dead Man

Aking and his queen had no children, though they were getting on in years. Half their life was already over. So the king decided he would pray to get an heir for his kingdom. He began his penances by standing in the middle of a tank on a twelve-yard stone, with another such stone on his head. He stood there like that for twelve whole years and prayed to Siva.

Siva said, “I’m burdened by this man’s devotion. His twelve years weigh on me. The stone on his head weighs on me. So I’ll go down and give him the child he wants.”

He came down from Kailasa, his mountain, to where the king stood steadfastly in the water.

“Come out of the tank,” Siva said. “I’ll give you a child.”

“I’ll come out only when you grant me the boon. Not till then.”

“All right, I give you my word,” said Siva, “but I’ll not give you the boon here. I’ll come to your house and grant your wish.” And he promised to visit the king, and sealed his promise by putting his hand in the king’s hand.

“Go home now and I’ll come tomorrow,” Siva said, and the king ended his penance, came out of the water, and went home to tell his wife.

“Siva has given me his word. He’ll come here tomorrow and give us children. Wash and wipe the whole palace, bathe, and offer worship. You must be ready tomorrow morning. Also, get five uttatti fruit.”

But his wife wouldn’t believe him. He insisted, “No, no, it’s true. Siva will come here himself. You’ll see.”

Next morning came very fast, and Siva did descend from the sky. As he walked towards the palace, he looked at himself, alms-bag on his shoulder, a cane in his fist, a trident slung on his back. “How can I go into the world looking like this?” he thought, changed into a holy man, and went begging from shop to shop before he reached the palace. The shopkeepers were devout and gave the holy man diamonds and pearls as gifts, but he wouldn’t touch them. He said, “What shall I do with these stones? If you wish, give me the fat of a flea and the fat of a bedbug. I’d like that.”

“Where shall we go for the fat of fleas and bedbugs?” the bewildered shopkeepers asked.

Meanwhile, Siva was dancing, leaping into the sky. He swayed like a peacock. But he would take nothing and asked only for the fat of fleas and bedbugs, which they couldn’t get. So he went hopping through the market all the way to the palace.

The king and queen were waiting. They washed his feet and fell at his feet. He gave the queen two betelnuts from his waist band and said, “This is for you. I know you want a child. What would you like? A smart son who’ll live only twelve years or an idiot who’ll live to be a hundred?”

She said, “What shall I do with an idiot son? He has to rule this kingdom. Give me a smart son for twelve years.”

“Think well. He’ll live only for twelve years, not a day longer. Once you’ve chosen, nothing can change it later. Think again.”

“I know what I want,” she said. “A smart son. Give him to me. I can’t wait.”

So Siva granted her a smart son who would live only for twelve years. The queen’s periods stopped, her pregnancy made her fuller by the day, and, exactly nine months and nine days later, she gave birth to a boy. Siva had decreed that a tiger would bring him his death on his twelfth birthday. The astrologers who could read such things also said so and warned his parents.

As a growing boy, he went out to play ball in town. The girls who were going to the river to fetch water said, “You’re the king’s son. What’s the matter with you? Playing ball with the ordinary town boys! As the prince of the kingdom, you’ve got to go to the forest and hunt lions, tigers, and such. Then you’ll be a real prince.”

So he went straight home, threw away the ball, and said to his mother, “Why didn’t anybody tell me what princes do? I’m going to hunt lions and tigers in the forest.”

The mother was panic-stricken. She remembered the prophecy. “My boy, you’re only twelve. Don’t think of hunting and wild animals. Don’t you have playmates? We’ll find you some.”

But he was obstinate and wouldn’t listen. He called for the servants, the stable boys, and prepared himself for a hunt. The mother said, “At least wait till I look at the omens.”

She went out to look for good omens, but all she saw were oil sellers, people carrying pickaxes and spades—bad omens. She came home and tried to stop the boy.

“I see only bad omens everywhere. Don’t go, my son. You can go tomorrow,” she pleaded.

She wept, she even fell at his feet and held on to them. But he wouldn’t hear any of it. He had already taken a step outside the threshold.

“See, Mother, I’ve already stepped outside. No real prince will take back his step and retreat inside. By your blessings, I’ll come home safely. You’ll see,” he said, touched her feet, and left for the forest, this twelve-year-old boy. His mother’s brother, his uncle, followed and joined him in the hunt.

The hunt was a fierce success. They brought down many tigers, lions, and gryphons, stood proudly on their carcasses, and loaded them in cart after cart to send them home. When the distraught mother saw these carts coming into the palace yard, filled with wild animals ripped apart by her son’s arrows, her heart revived. The cartmen said, “The prince has sent all these so that Your Highness may see and stop worrying about him. More are coming.”

“O Siva,” she said, relieved and happy. “That’s truly my son. He has killed so many tigers and lions in one hunt, his very first. They said a tiger would kill him. They were afraid even of a tiger in a picture, and removed all tiger pictures from the palace. How ridiculous!”

While she was exclaiming like this ecstatically, the prince had finished his hunt and was returning home. On the way, it occurred to him to stop at their family god’s temple and offer worship after his first adventure. As soon as he spoke of this plan, his uncle hurried before him. There were many pictures of tigers on the temple walls, and he knew that he could never stop his rash nephew from doing what he wanted. So he spattered the pictures with mud, and asked servants to hold curtains on either side of the prince as he entered the temple.

“Don’t look around and dillydally. Go straight to the god’s image, bow before it, and then let’s go home. It’s late,” said the uncle.

But did he listen? He prostrated himself before the god and as he turned back he saw the curtains. Impatiently, he tore them down, saying, “What’s all this curtain-holding? Are you afraid I’ll die? I’ve killed seven tigers today, remember?”

As he tore down the curtains, he saw tigers, tigers, tigers all around. They opened their mouths wide and rose from the pictures on the walls. When he saw their red tongues coming towards him, he became dizzy, fell into a swoon, and died on the spot.

His uncle cried and cried all the way, as he brought the body home.

“O Siva, I brought him safely till this point and yet couldn’t save him. My sister bore him in her old age, after so much trouble. Now he’s dead. What shall I do?”

The mother heard it all and ran out weeping.

“O Siva, you still took him as you said you would. After killing real tigers, he was killed by a tiger in a picture, just as they said. I wanted to see him married. Even now, I will. We’ll not bury him till we find a bride for him,” she said in her grief.

And even as they were preparing the bier and the chariot for the last procession of the dead boy, she sent a cartload of gold hitched to a camel with messengers: they had to find a bride, whatever the price.

The cartload went from street to street and from town to neighboring town, loudly announcing the search for a bride for the dead prince. The messengers finally met with a brahmin who had a twelve-year-old daughter named Chennavva. The poverty of the family was harsh beyond words. They said to the poor man, “Give us your daughter. We’ll unload the gold here.”

He agreed and gave them his daughter. At once her mother began to weep. She brought out a little oil in a cup, some turmeric, took her daughter in and gave her a ritual oil-bath, crying all the while, “O Daughter, widowhood is not for you. How can it be? You’re only twelve years old.”

Then she dressed her up in fresh clothes, put auspicious marks of turmeric and vermilion on her forehead, and blessed her, saying, “May you be like Savitri. May you keep your husband.” And she sent her with the royal messengers.

Galloping, they took her to the palace, where she was married in a proper ceremony to the dead boy. As in any wedding, they put auspicious marks of turmeric and vermilion on the bride’s face, threw grains of rice, and tied the wedding thread round her neck.

When it was time to lift the dead body and take it away, they wanted her to stay behind. But she refused to stay behind. Firmly, she said, “I’m going with my husband. Bury me with him. What’s the point of living without him?”

So she sat next to the body and was carried with it. As they reached the burial grounds, a great rainstorm descended on them. It seemed as if more water fell than the earth could hold. Everyone ran and found shelter from the wind and the rain. The dead body was left alone, and Chennavva held on to it. The night was dark, the place was a dismal burial ground, and she was alone with the body.

“What shall I do? This is my lot,” she said. She had sweated and her body was caked with mud. She sat down and scraped it, added more mud to it, then molded the image of Siva’s Bull with it. She installed it in front of her, sang songs, and worshiped the image with flowers she picked off the dead body. As she sang and worshiped, the mud image of the Bull was filled with life. He got up, snorted, and walked about. He said, “Chennavva, your devotion is great. I’d like to do something for you.”

And he went to heaven and pleaded with Siva, “Lord, you must give back Chennavva’s husband his life. You must give back her marriage to her. You must.”

“Dear Bull,” said Siva, “you’re quite taken with that Chennavva, aren’t you? We can’t give back life like that. Wait, let’s send her a tiger and let’s see what she does.”

So he sent a tiger to Chennavva. She at once stood with her back to her husband’s bier and, stretching out both her hands, prayed to the tiger, “Don’t eat him. Eat me.”

Which pleased the tiger too. He said, “We’ll send you Siva himself. You’re too good for us.”

The tiger went to Siva and pleaded: “O Siva, you must give back Chennavva’s husband his life.”

Then he sent lions, gryphons; he even sent she-demons, but she wasn’t afraid of any of them. She guarded her husband’s body and offered her own. When they all came back pleading her cause, Siva decided he would go down himself and see what she was like. He picked up his alms-bag and his cane and stood before her asking for alms. “What can I give this beggar, sitting here in the burial ground?” she thought, then took down the only precious thing she had on her, her wedding thread with its golden pendant (tali), and put it in his alms-bag.

“What’s this, you’ve given me your wedding tali? Don’t you have anything else to give?” said Siva, astonished.

She said, “No, Sir. That’s all I have. What else can I have, sitting here in the burial ground?”

Siva was touched. He tied the tali back on her neck, breathed life into her husband’s body, and went back to heaven. The young prince woke up as if from a long sleep. The happy couple talked all night till it dawned silver in the morning. They had much to talk about.

The people from the palace were worried all night about the body and the twelve-year-old girl they had left with it in the rainstorm. They came running as soon as the storm passed and it was light. They found the two of them talking. When they heard what had happened, they marveled at Chennavva, the power of her virtue, and how she had brought a dead man to life. His parents, summoned there by then, placed a coconut in the grave that had been dug and closed it up. The bride and bridegroom were carried back in palanquins to the palace and a whole new wedding was arranged.

When the time came for the bride to give the ritual offerings of bagina to her relatives, Chennavva said, “No one took my bagina earlier. I’m not going to give it to anyone now. I’ll give it to the river goddess, Ganges,” and took it to the river.

When the wedding took place the first time, no one had received her or her bridal gifts as they should have. Everyone in the town had shut their doors on her. Why should she give it now to anyone?

“I married a dead husband and no one thought of me then. Now I’m married to a live one, I’ll give bagina to the goddess and take gifts from her,” she said, and offered them to the river goddess. Then she came back, completed the wedding ceremony, and lived happily with her husband and her in-laws.

The breaking of the coconut

As an offering to the gods a coconut is at times smashed on the ground or on some object as part of an initiation or inauguration of building projects, facility, ship, the use of a new vehicle, bridge, etc.

It symbolizes the breaking of the ego. The coconut represents the human body and before the Lord it is shattered – breaking the ‘aham’ or ego (evil force) and symbolically total surrendering and merging with the Brahman – supreme soul. The juice within, representing the inner tendencies (vaasanas, lust) is offered along with the white kernel – the mind, to the Gods.

At the beginning of any auspicious task or a journey, people smash coconuts to propitiate Ganesha – the remover of all obstacles.

Hindus also break coconuts in temples or in front of idols in fulfillment of their vows.

During the annual Adi festival of Sri Mahalakshmi Amman temple at Mettumahadanapuram in Karur district, coconuts are broken on the heads of the devotees by the temple priests.

The coconut also symbolizes selfless service.

As following tale explains getting a coconut on the head can have serious consequences:

FABLE- Jataka tales: The Rabbit and the Coconut

There was once a rabbit who was sleeping beneath a coconut tree. All of a sudden a coconut fell down and landed on his head. The rabbit woke up, shrieking. “The sky is falling!” he shouted. “It’s the end of the world!”

The rabbit then ran off as fast as he could. Another rabbit saw him and asked, “What’s wrong, my friend?”

“It’s the end of the world!” the rabbit shouted. “The sky is falling!” The other rabbit raced after him, and soon hundreds of rabbits were running in fear.

A deer asked what had happened. “It’s the end of the world,” the rabbits shouted, and so that deer, and then hundreds of deer, started running with the rabbits.

The jackals joined in, as did the elephants. The animals ran shrieking together through the jungle. “The sky is falling! It’s the end of the world!”

Finally, they ran into the lion, who asked very calmly, “What are you all shouting about?”

“The sky is falling! It’s the end of the world!” they replied.

“Who told you that?” asked the lion.

“The jackals told us,” said the elephants.

“The deer told us,” said the jackals.

“The rabbits told us,” said the deer.

“And who told you?” he asked the rabbits.

The first rabbit crept forward and said, “I did, sir.”

“Show me!” ordered the lion.

The rabbit then led the lion to the tree, and he saw the coconut lying there. “Foolish rabbit,” he said, “the sky is not falling. It was just a coconut that hit you on the head.”

They then returned to the other animals and announced the good news. “The sky is not falling,” the rabbit shouted happily, “and it’s not the end of the world!”

In this way the lion saved the animals from themselves.

The coconut in festivals

Diwali, Dussera, Ganesh Chaturthi, Durga Puja, Holi – all these festivals mean a gigantic number of coconuts offered to the gods and to guests.

But the day which celebrates the coconut unfailingly is Nariyal Purnima in the Hindu month of Shravan. Officially, the full moon of this month is the close of the monsoon and the rains begin to abate from that day.

Along the west coast of India, fisher folk offer thousands of coconuts to the sea before setting out in their trawlers to resume their fishing operations.

The offering of the coconut is their prayer for safe sailing and prosperity. During the monsoon, fishermen of India often offer it to the rivers and seas in appeasing the sea God (Lord Varuna) with offerings of coconut during the monsoon.

In Manipur, on the day of Idd festival women take at least one fruit of coconut along with other eatables to their parents’ home.

In the tribal festival in Madhya Pradesh, the Gonds celebrate the festival of Meghnath, believed to be supreme God. Coconut along with lemon and turmeric are offered to Meghnath through the priest. Similarly, Gonds celebrate the festival of Bidri in the beginning of the calendar year.

In some places in Gujarat, on Dhuleti day, a game is played with a coconut. The players form two parties and stand opposite to one another with a coconut midway between them. Each party tries to take away the coconut, and prevents the other from doing so by throwing stones and cow-dung cakes.

The party which succeeds in taking away the coconut wins the game.

Taboos and beliefs

The Coconut is religiously so significant that the Hindus neither cut this tree nor do they use its wood for fuel. In Tamil Nadu, the uprooting of a coconut sapling is considered equivalent to killing one’s own son.

“If crack appears on the trunk within ten years, the planter would die.”

Possibly due to this belief it became a custom in Odisha to get coconuts planted by the oldest member of the family.

Coconut proverbs

Coconut is equally pervasive as rice, betel nut, and betel leaf and through its usefulness has penetrated the vocabulary of a number of languages such as Hindi, Punjabi, Sanskrit, Oriya, Tagalong, Hawaiian, Sinhalese, and Swahili in the form of proverbs and riddles.

“Coconuts do not grow upon pumpkin vine”

reminds that “Children turn out like their parents”.

A terse, emphatic, clear, and effective speech is

“Hitting of coconut on a stone” or “He speaks as effectively as the hitting of a stone on a coconut” or “His speech is like the breaking of cocoa nuts”

A Tamil proverb says: “Plant coconut trees, they feed you and your children.”

Thus coconut palm is an earning son to a poor retired man.

Planting coconut is like a life insurance policy that helps in old age. As it is said:

“Providence is more reliable than affection of a son”

and “If the child they have reared gives them no food, the child they have planted (i.e., the coconut palm) will feed them”

An Odissi proverb states about late bearing in coconut:

“A planter would never see his coconut palm at its full bearing stage.”

A Tamil proverb, “Oru kurumabaiyai kollarudhu, onpathu thennai nattathirku camam”

The killing of a kurumbai (an insect that feeds on coconut flowers) is equivalent to planting of nine coconut trees

conveys the local knowledge about the extent of damage caused due to insect attack.

Coconut riddles

Riddles not only test the wit and wisdom of a person but also convey the ingenuity of the people involved in their development. A number of riddles have been woven around coconut. A common riddle is prevalent in most Indian languages including Sanskrit:

“He has three eyes but not Shiva, he has long tresses but not a hermit, perches at the top of a tree but not a bird, gives milk but not a cow.”

From Odisha to Rajasthan and from Kashmir to Kerala and Tamil Nadu, throughout the length and breadth of the Indian subcontinent, this riddle and its variants prevail.

Coconut riddles are also equally popular and common in areas where coconuts are not grown.

~ Ahuja Siddharth. Ahuja Uma. Coconut – History, Uses, and Folklore. Asian Agri-History Vol. 18, No. 3, 2014.

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- Adi. Coconut in Hindu Mythology. http://www.indiatva.com/coconut-in-hindu-mythology

- Ahuja Siddharth. Ahuja Uma. Coconut – History, Uses, and Folklore. Asian Agri-History Vol. 18, No. 3, 2014.

- COCONUT PALM in Encyclopedia of Food Sciences and Nutrition (Second Edition). 2003.

- Different Uses for a Coconut. https://owlcation.com/stem/Different-Uses-for-a-Coconut

- Gupta Shakti M. Plant Myths & Traditions in India. 1968.

- Kalidasa – poems. 2012. Poemhunter.com – The World’s Poetry Archive.

- Kottankulangara Devi Temple. https://ipfs.io/ipfs/QmXoypizjW3WknFiJnKLwHCnL72vedxjQkDDP1mXWo6uco/wiki/Kottankulangara_Devi_Temple.html

- Mahabharata.

- Pancha Dravida Brahmana Mahasabha. http://panchadravida.com/hindu-dharma-interconnected-stories/

- Ramachander P.R. Chottanikkara Bhagawathy Temple. https://web.archive.org/web/20240724215226/https://hindupedia.com/en/Chottanikkara_Bhagawathy_Temple

- Ramanujan, A. K. A Flowering Tree and Other Oral Tales from India. Berkeley London: University of California Press. 1997.

- The ell and the coconut tree. http://www.kidsgen.com/stories/folk_tales /the_ell_and_the_coconut_tree.htm#Dx0ZilAxlxvVm0Be.99

- Upadhyaya K. D. Indian Botanical Folklore. Asian Folklore Studies, Vol. 23, No. 2 .1964. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1177747[