Turkish Coffeehouses were places for men to drink coffee, to meet, to do business, to discuss politics, art and literature. Even prohibition could not stop the habit to visit coffeehouses in Istanbul and elsewhere in the Ottoman empire. Discover the History and Evolution of the Turkish Coffeehouse

In this Article

Neither coffee nor the coffeehouse is the heart’s behest

Turkish, Anonymous

The heart seeks friendship – coffee is a pretext

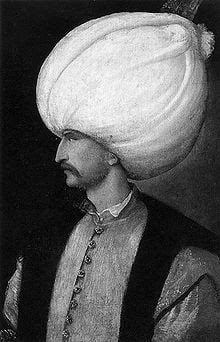

Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent

After successfully defeating the Marmeluks in Egypt in 1517 the Ottomans acquired a country of historic and cultural development.

A nation that was drinking coffee, with all things that come with the capture of a new nation, the coffee beans and brew naturally came with it.

Ottoman royalty first encountered coffee culture on Yavuz Sultan Selim’s Egyptian campaign in 1516-1517, but the drink didn’t begin to enter regular use in the Ottoman palace until the reign of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent.

Özdemir Pasha, the Ottoman Governor of Yemen, had grown to love the drink while stationed there, he introduced the Sultan to coffee.

Coffee became the shining star of the court’s social life, and the sultan appointed his own kahvecibasi (kahvecibaşı) to prepare the imperial cup of Turkish coffee (Türk Kahvesi, kahve) .

It is reported that the kahvecibasi (coffee maker) had over 40 assistants to prepare and serve coffee for the sultan and his court.

Coffee became ritualized. The kahvecibasi was added to the roaster of court functionaries. The chief coffee maker’s duty was to brew the Sultan’s or his patron’s coffee, and was chosen for his loyalty and ability to keep secrets.

The annals of Ottoman History record a number of Chief Coffee Makers who rose through the ranks to become Grand Viziers to the Sultan.

Lee Stewart Allen quotes: The sultan, Portal of Eternal Light to his friends, had a slightly more elaborate coffee ceremony involving up to thirty people, including a First Minister of the Coffee, according to Souvenir sur le harem imperial by Leila Hanoum:

It arrives already prepared in a golden coffee pot (ibrik) which rests on coals contained in a golden basin hung from three chains which are gathered at the top and held by a slave.

Two other girls hold golden trays with little coffee cups made of fine Savoy or Chinese porcelain.

The First Minister of the Coffee takes a zarf from the tray, places a cup in it and then, with a small piece of quilted linen that is always on the tray, she pours the coffee.

Next, with her fingertips she grasps the base of the zarf, which rests on the end of her index finger supported by the tip of her thumb, and offers it to the Sultan with a gesture of infinite grace and dexterity.

Nasreddin Hodscha meets the kahvecibasi

The wise fool has an amusing story about the kahvecibasi:

The Mullah meets a friend on the street: “Oh, it’s been a long time….how are you? what are you doing?”

“Oh I am fine, thank you Mullah. Now I’m working at the palace of the Sultan, as the representative of the representative of the coffee maker”.

“Ah, I see. And then what will you become?”

“Then I become the representative of the coffee maker”.

“And then?”

“Oh I become the coffee maker for the Sultan.”

“And then?”

“I become the secretary”.

“Ah good, and then?”

“And then… I become a minister”.

“And then?”

“Oh Mullah! and then I become the visir”.

“Ah and then?”

“Well, and then I become the Sultan!”

“And then?”

“Mullah! And then, and then nothing! There is nothing after the Sultan!”

“You see? That is where I’ve already reached… nothing”.

Read Nasreddin Hodscha coffee stories.

Türk Kahvesi in Constantinople – Istanbul

Constantinople– Istanbul you will find both names here, that is why:

Bazantion (also spelled Byzantion) was founded it in 657 BC by the Greeks, with the Romans taking over it was latinized Byzantium. It’s also been called New Rome and Augusta Antonina, in honor of a Roman emperor’s son. Then the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great — the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity — named it Constantinople after himself around the year 330.

The Ottomans didn’t officially change the name of Constantinople and called Istanbul ‘Kostantiniyye,’when they took over in the 15th century. People elsewhere in the empire began to use the word “Istanpolin,” which means “to the city” in Turkish (from the Greek “to The City” or “eis tan polin”) to colloquially describe the capital of Ottoman imperial power. Progressively, Istanpolin became used more, but the official name remained Constantinople. The vernacular changed little by little, and so Istanpolin eventually became Istanbul. Following its defeat in World War I, the sultanate of the Ottoman Empire was abolished in 1922, and the Republic of Turkey was born in 1923. In 1930 Istanbul became the city’s official name.

The palace coffee ritual was ornate, featuring incense, rose-flavored lokum (Turkish delight), and rosewater cologne, while the coffee itself was flavored with mastic (plant resin), cardamom, or ambergris (whale vomit).

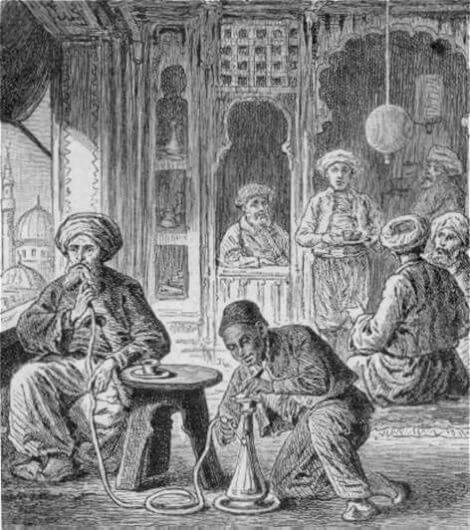

To heighten their patrons’ pleasure, Constantinople’s cafés offered “special” coffees containing faz ’abbas, a blend of seven drugs and spices that included pepper, opium, and saffron. Other treats included honey-hash balls and sheera, hash or marijuana mixed with tobacco, which could be smoked in water pipes—or mixed into coffee, creating an Islamic speedball, a “life-giving thing…which they [addicts] were willing to die for,” according to famed Ottoman writer Katib Celebi.

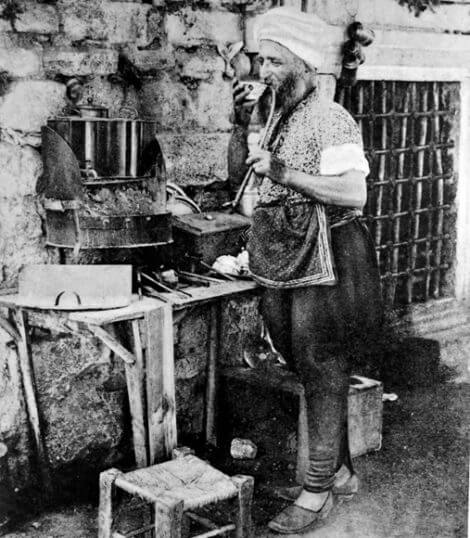

The preparation of Kahve – Turkish Coffee

This was the birth of Türk Kahvesi, Turkish Coffee – a particular preparation of the new drink that involves roasting the fresh beans over a fire, grinding them finely, and then boiling the ground beans slowly over charcoal embers.

Turkish coffee does not mean coffee produced in Turkey, but the method of making it: the roast level and grinding of the beans”

A small pot with a long handle called cezve and a small coffee cup called fincan or zarf with its saucer is needed. As the coffee starts to boil, foam rises on top. If there are guests, it is important that they get plenty of the wesh, or crema on top. This foam is the distinctive feature of a good Turkish coffee, which today is served with a glass of water and accompanied by Lokum – Turkish delight.

In Turkish coffee, the beans are grounded even finer than in Italian espresso, this makes it possible to serve the coffee with the grounds. The grounds settle and do not enter the mouth.

In Ottoman times the drink was served thick, bitter, and near-boiling, with no sugar. Cardamom was the only spice added with any frequency, although in some disreputable quarters, opium and hashish apparently were also stirred in.

Harem women received intensive training on the proper technique of preparing Turkish coffee. Valide Sultan, the mother of the Sultan, had her own private coffeehouse in the palace.

Coffee’s reknown soon spread beyond the palace, grand mansions, markets and homes, till today…

Coffee plays a major role in everyday life, whether it’s in the form of “morning coffee” (sabah kahvesi), “pleasure coffee” (keyif kahvesi) or “fatigue coffee” (yorğunluk kahvesi).

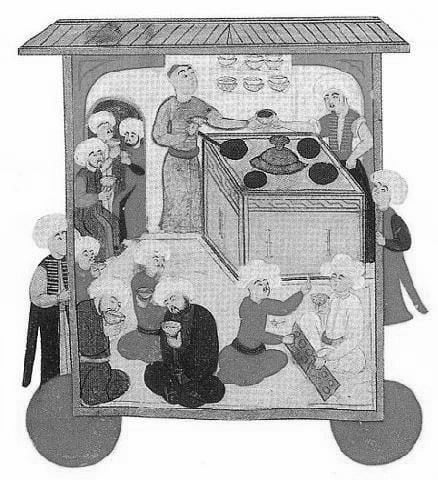

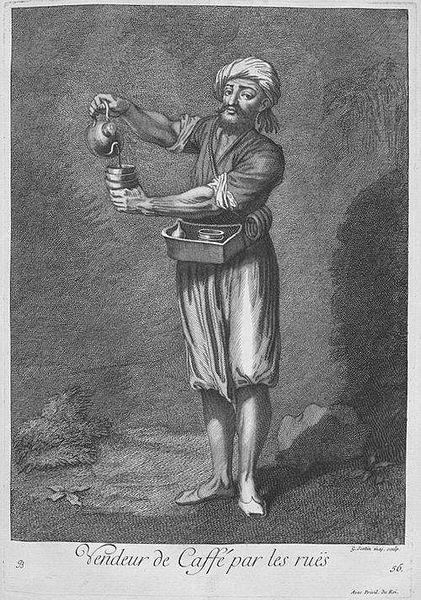

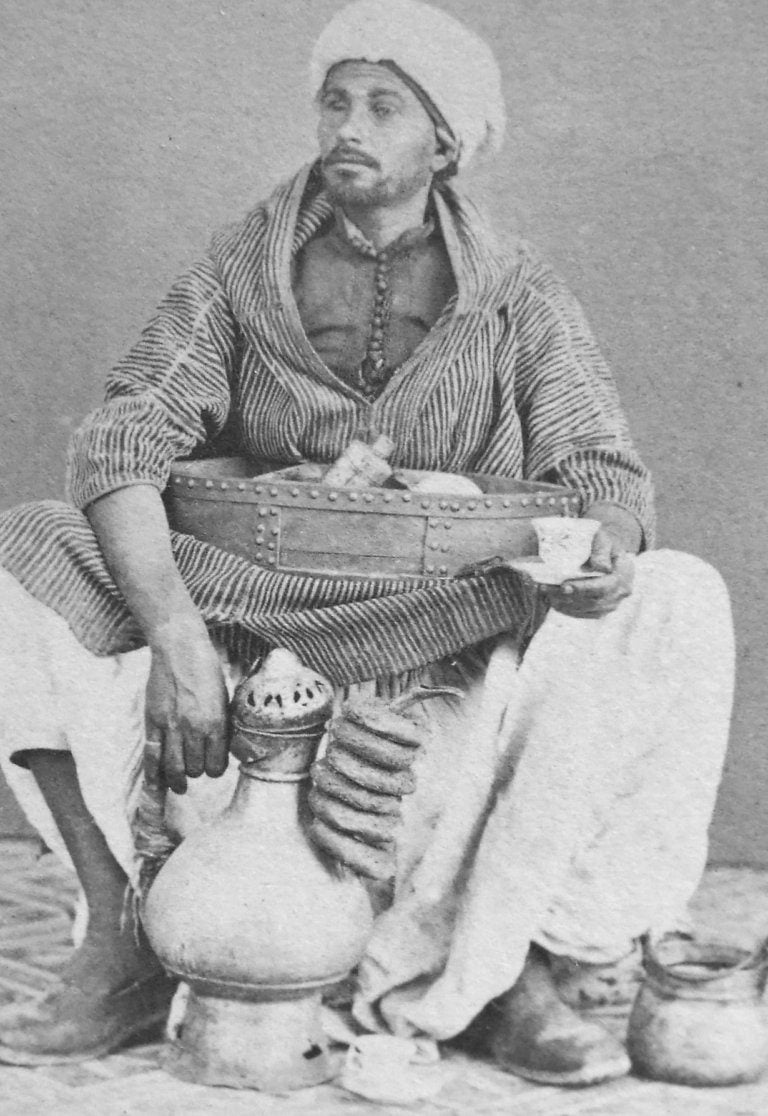

Street Coffee sellers

Street vendors served meandering locals in markets throughout Constantinople. Customers walked up to the portable booth or coffee was delivered to various places within the market. Transporting the hot drink around a crowded bazaar required

“hustling through the streets and alleys carrying cups and single-serving pots in a tray, usually suspended at three points along its circumference by chains or a sort of frame.”

The engraving from the seventeenth century features a coffee vendor. Baptiste’s artwork depicted a tray secured around the vendor’s waist which held extra cups and a small burner with which to brew the coffee.

The vendor would pour a pot of coffee into traditional china cups and deliver them to customers. On the coffee pot, there are Simits, sesame crusted, circular breads, They also go by the names Turkish bagel, Gevrek (crisp) or Koulouri (Greek language).

Small Coffee Shops

Vendors of Türk Kahvesi appeared in the bazaar with large copper vessels with fire under them; and those who had a mind to drink were invited to use a little stool or step into any neighboring shop where every one was welcome to enjoy his cup.

Coffee’s success and integration into Ottoman culture was finally given by the coffeehouses kahvehane.

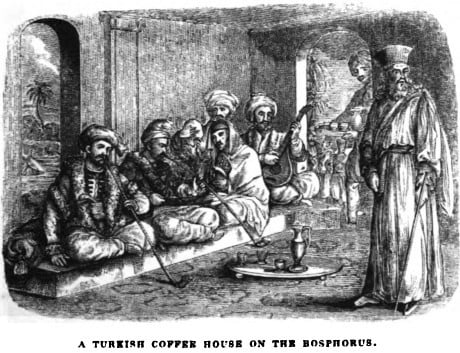

The first Coffeehouses of Constantinople

The world’s first coffee shop, legend goes, Kiva Han opened in Constantinople in 1475, but there is no written documentation about this event.

Ottoman historian Ibrahimi Pechevi, wrote that two Syrian merchants named Hakem and Şamlı, opened the first coffeehouse in Constantinople some time between 1551 and 1560.

“About that year, a fellow called Hakam from Aleppo and a wag called Shams from Damascus came to the city; they each opened a large shop in the district called Tahtakale, and began to purvey coffee.”

Ibrahimi Pechevi

Documented is also where in the district of Taht-ul-kale. “Taht-ul Kale” means “inside the castle”, and is known today as Tahtakale. Many coffee vendors set up shop on Tahtakale’s Tahmis Sokak, which today means “Roasted and Ground Coffee Street.”

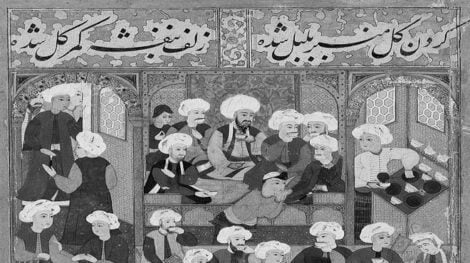

“They were wonderful institutions for those days, remarkable alike for their furnishings and their comforts, as well as for the opportunity they afforded for social intercourse and free discussion. Schemsi and Hekem received their guests on “very neat couches or sofas,”

and the admission was the price of a coffee—an amount, witch most costumer could afford.

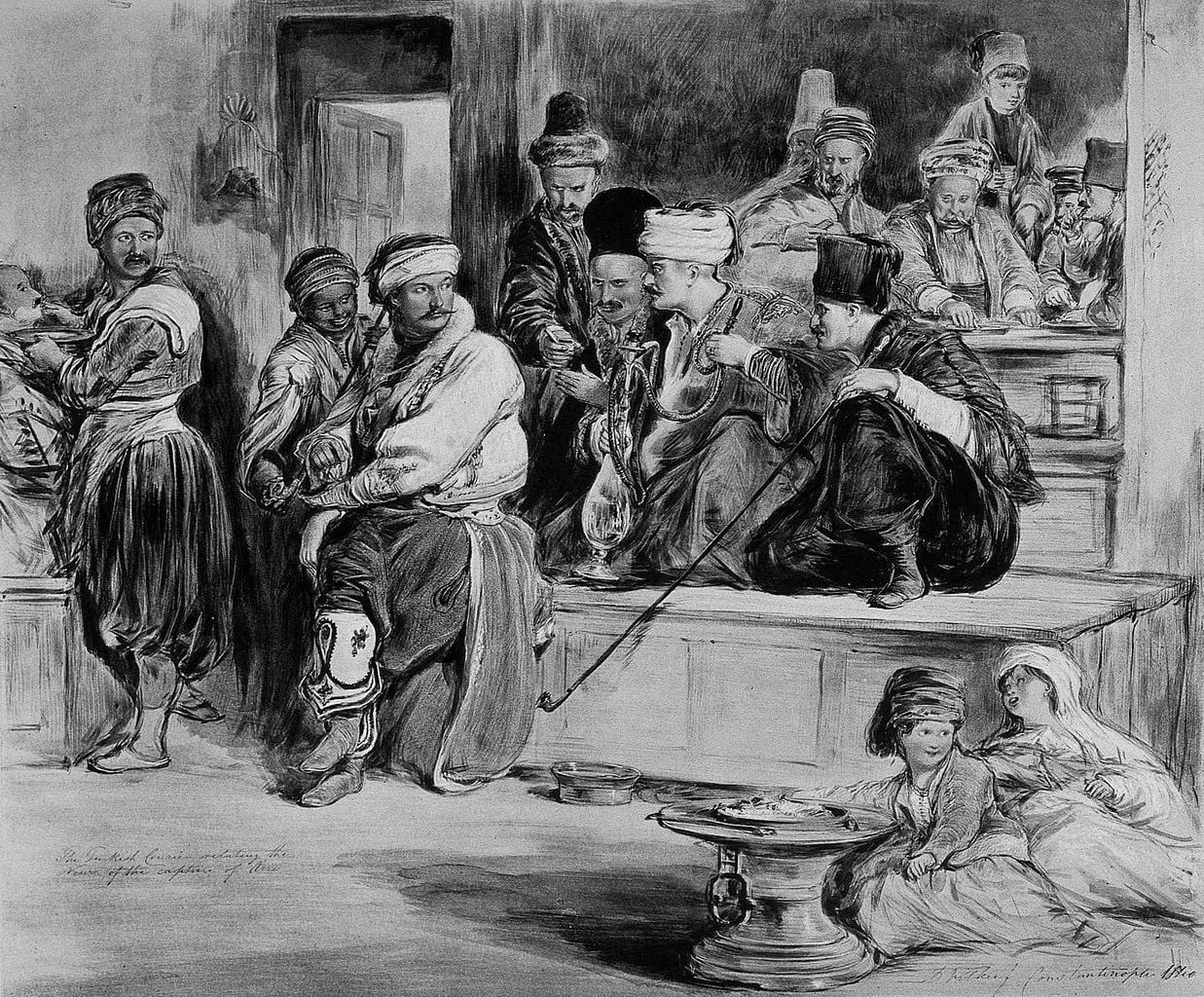

The Ottomans called the coffeehouse kahveh kane, and as they grew in popularity, they became more and more luxurious. There were lounges, richly carpeted; and in addition to coffee, many other means of entertainment. To these “schools of the wise” came the “young men ready to enter upon offices of judicature; kadis from the provinces, seeking reinstatement or new appointments; muderys, or professors; officers of the seraglio; bashaws; and the principal lords of the port.”

The Coffee house became home of intellectual, where they could flock and have conversations and debates, share new findings and information. Not to mention merchants and travelers from all parts of the then known world. The Ottomans were merely the first to commercialize coffee.

Constantinople was a center of cultural integration and coffee drew from multiple cultural traditions.

Coffee beans were grown in the Arabian Peninsula outside of the Ottoman Empire, brewed within Constantinople, and sipped from exotic cups known as China.

As a port city situated within the confluence of Mediterranean trade, Constantinople imported many goods available to the general public, like tobacco, opium, tea, spices and cacao, yet none of these goods met with the same success as coffee.

“Turks wearing salwar pantaloons, tabards, and fezes; Turks with wide foreheads, thick eyebrows and thick napes; Turks with long silver watch chains, their wide knees splayed to the sides, seated on little stools, their hookah pipes set up, sipping with great, deep pleasure from large cups.

A tiny, disheveled apprentice coffeehouse waiter with rolled up sleeves, an apron at his waist and wearing a fez deftly beats out some warbling melody with the two ends of the tongs in his hand: he wanders about exclaiming “The lords are coming.”

~ Heyin Rahmi Gürpınar, Hayattan Sayfalar- Pages From Life.

Woman in Coffeehouses in Constantinople

Coffee culture had significant social importance- Turkish Coffeehouses transformed urban life, changed patterns of social interaction, introduced a new process of socialization, and rearranged urban spaces.

Over time, the habit of drinking coffee became a dispensable part of the daily life of Muslim men in coffeehouses and Muslim women at home, as they were not taking active part of public life. With a few exceptions, like female owners of bakeries or small grocery shops, or as vendors of homemade products, door to door.

“Coffeehouses were public places where men (but rarely women) of nearly every social background came together to pass the time over a few leisurely cups.”

When women did enter coffeehouses, they were generally Christian or Jewish rather than Muslim and were there to perform – either as musicians, dancers or storytellers – rather than to socialize.

Beautiful servant women and female Slaves were used in some luxury Coffeehouses of Constantinople.

Despite the creation and dissemination of culture that took place within coffeehouses, half of the population, Muslim women, were mostly left out.

Behind the walls of a home or a harem they enjoyed their coffee anyway.

In Ottoman times women could ask for a divorce if the husband would not provide for her daily coffee.

Swedish traveler Mouradgea D’Ohsson described over 600 coffeehouses existing in Constantinople in the 1570s, only fifteen years after coffee first arrived in Istanbul.

Coffee Prohibition

Various political and religious authorities shut down the coffeehouses over the next hundred years.

Coffee was banned, Coffee houses closed, seller beaten, drinkers flogged.

Since legendary Sufis of Yemen first began using coffee in the mid 15th century, the bean had already been banned more than twice in belief of its blasphemous role as an intoxicating beverage in the eyes of Islam.

By the 15th century there were coffee houses from Mecca to Cairo, and then to the capital of the Ottoman Empire, Constantinople- Istanbul.

Coffee prohibition in Arabia

From the very beginning, the prospect of people coming together to simply talk and share ideas was a problematic one for some rulers.

Mecca 1511

As early as 1511, the leader of Mecca, Khair-Beg (Kha’ir Bega), outlawed coffee and forced all the public coffeehouses to close.

The governor Khair-Beg organized a trial: a basket of coffee seating in one side and a prosecutor in the other. The basket had no way to reply to the accuse of making its drinkers lose control of themselves and thus lose vision of Allah.

Coffee got prohibited, but this didn’t stop the people to drink it. However, historians point out that the ban came right after Khair-Beg discovered that negative sentiments about him and his rule were being spread through the coffeehouses.

Finally the governor of Cairo, a heavy coffee drinker, overturned the decision, dismissed the governor and saved the coffeehouses. Also, he placed a heavy taxation on the coffeehouses as an extra income to the State.

Mecca 1535

In 1535, another attempt was made to ban the drink. This time, it wasn’t about politics. It was about religion. Coffee houses originally began as places for religious meetings and conversation. But religion wasn’t the only topic of those conversations.

About 1570, just when coffee seemed settled for all time in the social life, the imams and dervishes raised a loud wail against it, saying

“the mosques were almost empty, while the coffee houses were always full”,

also because of its stimulating effect, coffee, like hashish or alcohol, was considered haram, forbidden by Islamic law, sometimes called Hanafi Law. In the fifth surah of the Holy Quran, the sacred book of Islam, verse 90 forbids the drinking of “intoxicants.”

Coffee prohibition in The Ottoman Empire 1536

During this time, the Ottoman Empire ruled over parts of the Middle East.

The Ottoman government outlawed the export of fresh, fertile coffee seeds from Yemen, where the trees were grown. All harvested berries — coffee beans are the seeds in the berries — had to be either partially roasted or steeped in boiling water. By doing this, the seeds couldn’t be germinated outside of Yemen.

The export ban lasted until the 1600s.

Legendary Sufi Saint Baba Budan successfully smuggled fertile coffee seeds to India.

Constantinople 1543

Sultans in the Ottoman Empire tried to ban the substance, but failed due to wide support of the people of coffee. Despite a fatwa from chief cleric Ebussuud Efendi in 1543, that caused shiploads of coffee beans to be dumped into the sea in Constantinople.

Constantinople 1633

Legend has it, that Sultan Murad IV (1623-40) would cut off the heads of the unfortunate coffee drinker as they sipped it.

It is said, that he would sometimes even disguise himself as a commoner and wander the nighttime streets of Constantinople while carrying a 100-pound broadsword. If he found a coffee drinker, he’d behead them on the spot.

Later Kupril was more lenient, public coffee drinking no longer resulted in immediate death. First-time offenders merely received a light beating by cudgel. A second time, the perpetrator was sewn into a leather bag and dumped in the sea. Strangely enough, while he suppressed the coffeehouses, he permitted the taverns, that sold wine forbidden by the Holy Quran, to remain open. Perhaps he found the latter produced a less dangerous kind of mental stimulation than that produced by coffee.

Coffee, says Virey, was too intellectual a drink for the fierce and senseless administration of the Pashas. After several attempts to ban the bean, the Ottoman Empire gave into its newfound coffee culture, also because of the rich tax revenues coming from the Coffeehouses in Constantinople – Istanbul.

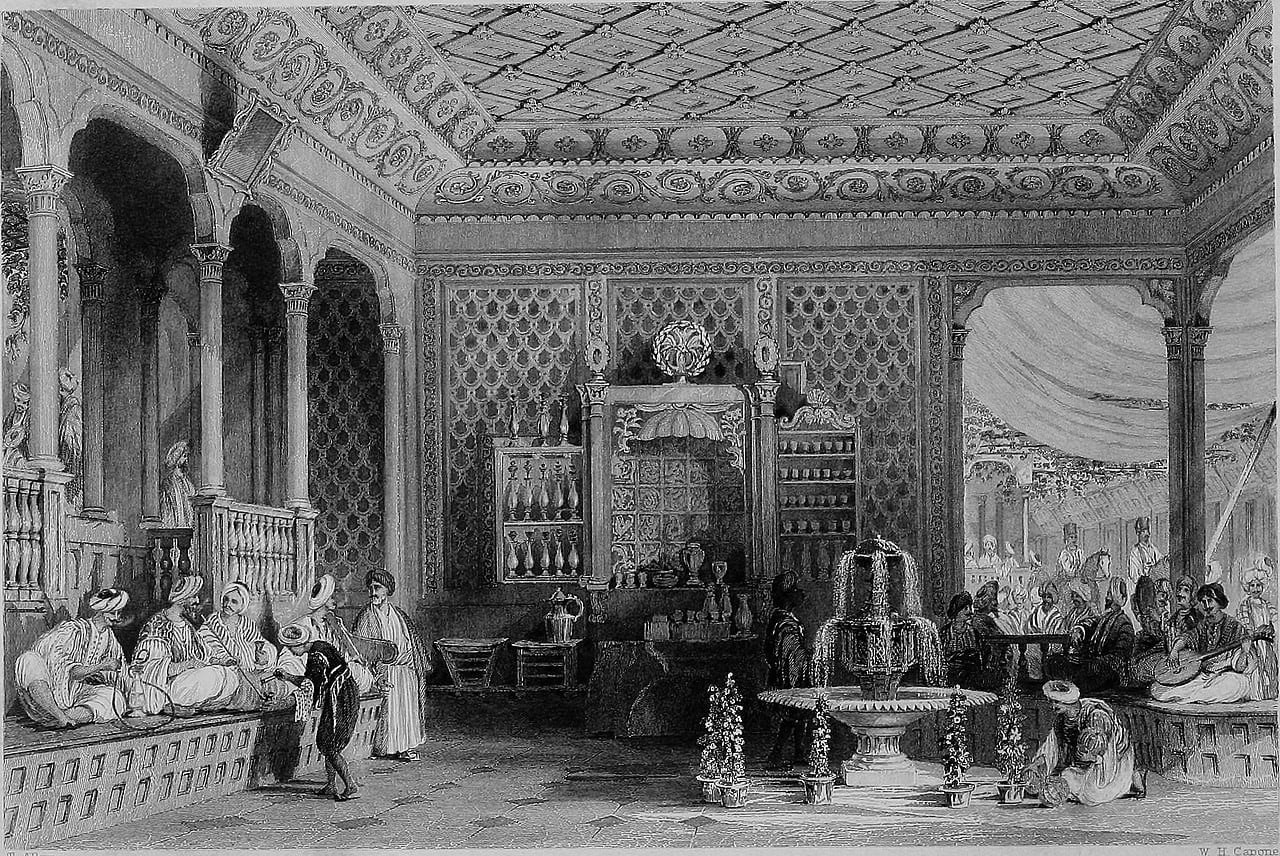

The grand Coffeehouses in Constantinople – Istanbul

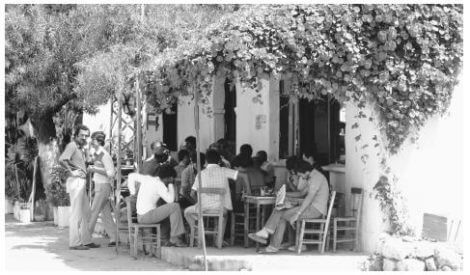

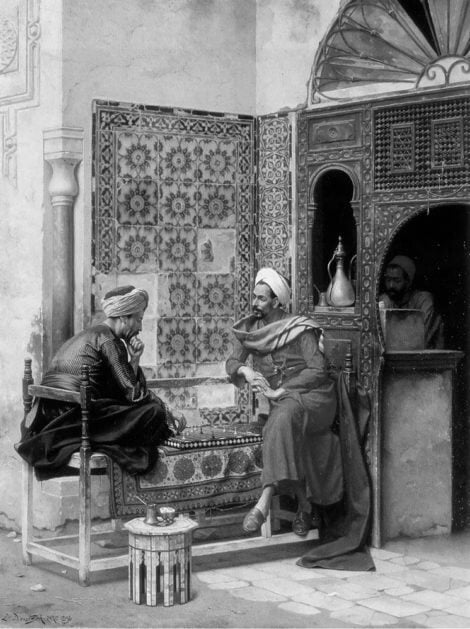

Elegant Turkish coffeehouses in Constantinople were square-shaped and surrounded by large sofas on three sides called “peyke.” Clients took off their shoes and sat on the peykes. There was an oven in one corner where coffee and narghile (hookah) were prepared. Generally, coffeehouses featured an open space under the shade of a willow tree for summers. Apart from small peykes, these open spaces also had cane chairs.

Coffee and narghile were the main treats of coffeehouses. Tea found its place in Ottoman society toward the end of the 19th century. However, all these were an excuse to get together. Thus, these verses were always written on the walls of the coffee houses:

“The heart desires neither coffee nor coffeehouse. The heart only desires companionship, coffee is only the excuse.”

Constantinople’s passion for coffee has remained unchanged over the centuries. At the end of the 18th century, the Italian writer Edmondo de Amicis wrote:

“There are coffeehouses at the summits of the Galata and Beyazıt Towers, there are coffee vendors on the ferries, in the cemeteries, in government offices and Turkish baths – even in the markets. No matter where you are in Istanbul, all you have to do is yell ’Coffee Maker’ with nary a glance in any direction, and within three minutes you will be clutching a steaming cup of coffee.”

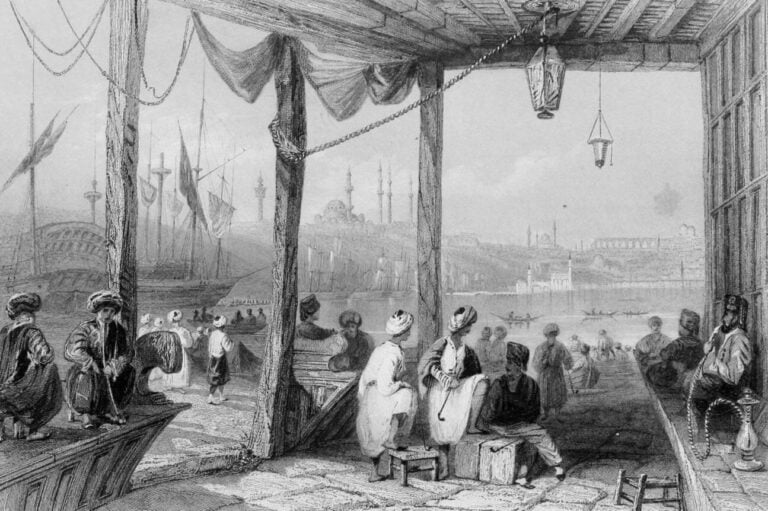

“The caffinet, or coffee-house, is something more splendid, and the Turk expends all his notions of finery and elegance on this, his favorite place of indulgence. The edifice is generally decorated in a very gorgeous manner, supported on pillars, and open in front. It is surrounded on the inside by a raised platform, covered with mats or cushions, on which the Turks sit cross-legged.

On one side are musicians, generally Greeks, with mandolins and tambourines, accompanying singers, whose melody consists in vociferation; and the loud and obstreperous concert forms a strong contrast to the stillness and taciturnity of Turkish meetings.

On the opposite side are men, generally of a respectable class, some of whom are found here every day, and all day long, dozing under the double influence of coffee and tobacco.”

The coffee is served in very small cups, not larger than egg-cups, grounds and all, without cream or sugar, and so black, thick, and bitter that it has been aptly compared to “stewed soot”.

Besides the ordinary chibouk for tobacco, there is another implement, called narghillai, used for smoking in a caffinet…”

H.G. Dwight writing in 1916, on the Turkish coffee house, says:

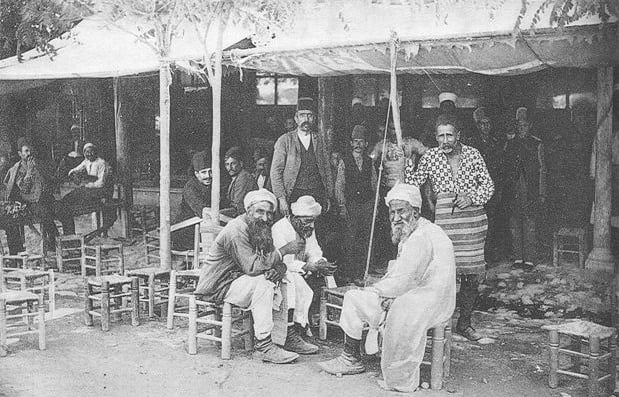

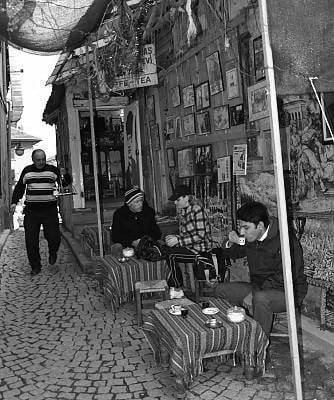

“There are thoroughfares in any Turkish city that carry on almost no other form of traffic. There is no quarter so miserable or so remote as to be without one or two. They are the clubs of the poorer classes. Men of a street, a trade, a province, or a nationality—for a Turkish coffee-house may also be Albanian, Armenian, Greek, Hebrew, Kurd, almost anything you please—meet regularly when their work is done, at coffee-houses kept by their own people. So much are the humbler coffee-houses frequented by a fixed clientèle that a student of types or dialects may realize for himself how truly they used to be called Schools of Knowledge.” The arrangement of a Turkish coffee-house is of the simplest. The essential is that the place should provide the beverage for which it exists and room for enjoying the same. A sketch of a coffee-shop may often be seen on the street, in a scrap of shade or sunshine according to the season, where a stool or two invite the passer-by to a moment of contemplation.

Larger establishments, though they are rarely very large, are most often installed in a room longer than it is wide, having as many windows as possible at the street end and what we would call the bar at the other. It is a bar that always makes me regret I do not etch, with its pleasing curves, its high lights of brass and porcelain striking out of deep shadow, and its usually picturesque kahvehji. You do not stand at it. You sit on one of the benches running

“There are thoroughfares in any Turkish city that carry on almost no other form of traffic. There is no quarter so miserable or so remote as to be without one or two. They are the clubs of the poorer classes. Men of a street, a trade, a province, or a nationality—for a Turkish coffee-house may also be Albanian, Armenian, Greek, Hebrew, Kurd, almost anything you please—meet regularly when their work is done, at coffee-houses kept by their own people. So much are the humbler coffee-houses frequented by a fixed clientèle that a student of types or dialects may realize for himself how truly they used to be called Schools of Knowledge.” The arrangement of a Turkish coffee-house is of the simplest. The essential is that the place should provide the beverage for which it exists and room for enjoying the same. A sketch of a coffee-shop may often be seen on the street, in a scrap of shade or sunshine according to the season, where a stool or two invite the passer-by to a moment of contemplation.

Larger establishments, though they are rarely very large, are most often installed in a room longer than it is wide, having as many windows as possible at the street end and what we would call the bar at the other. It is a bar that always makes me regret I do not etch, with its pleasing curves, its high lights of brass and porcelain striking out of deep shadow, and its usually picturesque kahvehji. You do not stand at it. You sit on one of the benches running

down the sides of the room. They are more or less comfortably cushioned, though sometimes higher and broader than a foreigner finds to his taste. In that case you slip off your shoes, if you would do as the Romans do, and tuck your feet up under you. A table stands in front of you to hold your coffee—and often in summer an aromatic pot of basil to keep the flies away. Chairs or stools are scattered about. Decorative Arabic texts, sometimes wonderful prints, adorn the walls. There may even be hanging rugs and china to entertain your eyes. And there you are.

The habit of the coffee-house is one that requires a certain leisure. You must not bolt coffee as you bolt the fire-waters of the West, without ceremony, in retreats withdrawn from the public eye. Being a less violent and a less shameful passion, I suppose, it is indulged in with more of the humanities. The etiquette of the coffee-house, of those coffee-houses which have not been too much infected by Europe, is one of their most characteristic features. Something like it prevails in Italy, where you tip your hat on entering and leaving a caffè. In Turkey, however, I have seen a new-comer salute one after another each person in a crowded coffee-room, once on entering the door and again after taking his seat, and be so saluted in return—either by putting the right hand to the heart and uttering the greeting Merhabah, or by making the temennah, that triple sweep of the hand which is the most graceful of salutes. I have also seen an entire company rise upon the entrance of an old man, and yield him the corner of honor.

Such courtesies take time. Then you must wait for your coffee to be made. To this end coffee, roasted fresh as required by turning in an iron cylinder over a fire of sticks and ground to the fineness of powder in a brass mill, is put into a small uncovered brass pot with a long handle. There it is boiled to a froth three times on a charcoal brazier, with or without sugar as you prefer. But to desecrate it by the admixture of milk is an unheard of sacrilege. Some kahvehjis replace the pot in the embers with a smart rap in order to settle the grounds. You in the meanwhile smoke. That also takes time, particularly if you “drink” a narguileh, as the Turks say.

When your coffee is ready it is poured into an after-dinner coffee-cup or into a miniature bowl, and brought to you on a tray with a glass of water. A foreigner can almost always be spotted by the manner in which he finally partakes of these refreshments. A Turk sips his water first, partly to prepare the way for the coffee, but also because he is a connoisseur of the former liquid as other men are of stronger ones. And he lifts his coffee-cup by the saucer, whether it possess a handle or no, managing the two together in a dexterous way of his own. The current price for all this, not including the water-pipe, is ten paras—a trifle over a cent—for which the kahvehji will cry you “Blessing”.

More pretentious establishments charge twenty paras, while a giddy few rise to a piaster—not quite five cents—or a piaster and a half. That, however, begins to look like extortion. And mark that you do not tip the waiter. I have often been surprised to be charged no more than the tariff, although I gave a larger piece to be changed and it was perfectly evident that I was a foreigner. That is an experience which rarely befalls a traveller among his own coreligionaries. It has even happened to me, which is rarer still, to be charged nothing at all, nay, to be steadfastly refused when I persisted in attempting to pay, simply because I was a foreigner, and therefore a guest.

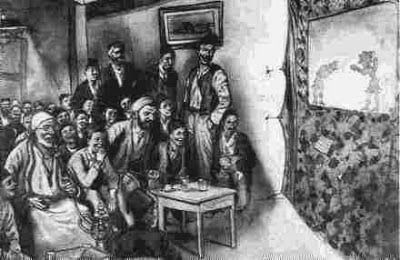

There is no reason, however, why you should go away when you have had your coffee—or your glass of tea—and your smoke. On the contrary, there are reasons why you should stay, particularly if you happen into the coffee-house not too long after sunset. Then coffee-houses of the most local color are at their best. Earlier in the day their clients are likely to be at work. Later they will have disappeared altogether. For Constantinople has not quite forgotten the habits of the tent. Stamboul, except during the holy month of Ramazan, is a deserted city at night. But just after dark it is full of a life which an outsider is often content simply to watch through the lighted windows of coffee-rooms.

These are also barber-shops, where men have shaved not only their chins, but different parts of their heads according to their “countries”.

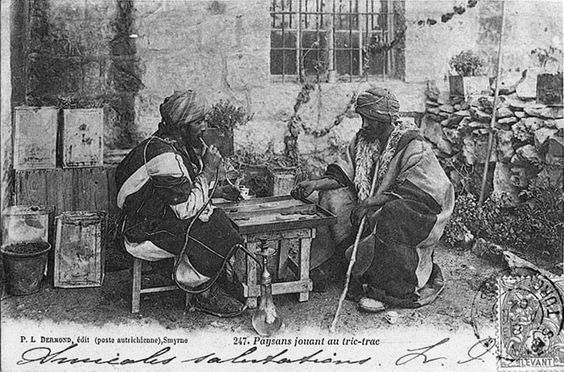

In them likewise checkers, the Persian backgammon, and various games of long narrow cards are played. They say that Bridge came from Constantinople. Indeed, I believe a club of Pera claims the honor of having communicated that passion to the Western World. But I must confess that I have yet to see an open hand in a coffee-house of the people.

One of the pleasantest forms of amusement to be obtained in coffee-houses is unfortunately getting to be one of the rarest. It is that afforded by itinerant story-tellers, who still carry on in the East the tradition of the troubadours. The stories they tell are more or less on the order of the Arabian Nights, though perhaps even less suitable for mixed companies—which for the rest are never found in coffee-shops. These men are sometimes wonderfully clever at character monologue or dialogue. They collect their pay at a crucial moment of the action, refusing to continue until the audience has testified to the sincerity of its interest by some token more substantial.

Music is much more common. There are those, to be sure, who find no music in the sounds poured forth oftenest by a gramophone, often by a pair of gypsies with a flaring pipe and two small gourd drums, and sometimes by an orchestra so-called of the fine lute—a company of musicians on a railed dais who sing long songs while they play on stringed instruments of strange curves. For myself I know too little of music to tell what relation the recurrent cadences of those songs and their broken rhythms may bear to the antique modes. But I can listen, as long as musicians will perform, to those infinite repetitions, that insistent sounding of the minor key. It pleases me to fancy there a music come from far away—from unknown river gorges, from camp-fires glimmering on great plains. Does not such darkness breathe through it, such melancholy, such haunting of elusive airs? There are flashes too of light, of song, the playing of shepherd’s pipes, the swoop of horsemen and sudden outcries of savagery. But the note to which it all comes back is the monotone of a primitive life, like the day-long beat of camel bells. And more than all, it is the mood of Asia, so rarely penetrated, which is neither lightness or despair.

There are seasons in the year when these various forms of entertainment abound more than at others, as Ramazan and the two Bairams. Throughout the month of Ramazan the purely Turkish coffee-houses are closed in the daytime, since the pleasures which they minister may not then be indulged in; but they are open all night. It is during that one month of the year that Karaghieuz, the Turkish shadow-show, may be seen in a few of the larger coffee-shops. The Bairams are two festivals of three and four days respectively, the former of which celebrates the close of Ramazan, while the latter corresponds in certain respects to the Jewish Passover. Dancing is a particular feature of the coffee-houses in Bairam. The Kurds, who carry the burdens of Constantinople on their backs, are above all other men given to this form of exercise—though the Lazzes, the boatmen, vie with them. One of these dark tribesmen plays a little violin like a pochelle, or two of them perform on a pipe and a big drum, while the others dance round them in a circle, sometimes till they drop from fatigue. The weird music and the picturesque costumes and movements of the dancers make the spectacle one to be remembered.

Other types of Coffeehouses in Constantinople – Istanbul

“Christian coffee-houses also have their own festal seasons. These coincide in general with the festivals of the church. But every quarter has its patron saint, the saint of the local church or of the local holy well, whose feast is celebrated by a three-day panayiri. The street is dressed with flags and strings of colored paper, tables and chairs line the sidewalk, and libations are poured forth in honor of the holy person commemorated. For this reason, and because of the more volatile character of the Greek, the general note of his merrymaking is louder than that of the Turk. One may even see the scandalous spectacle of men and women dancing together at a Greek panayiri. The instrument which sets the key of these orgies is the lanterna, a species of hand-organ peculiar to Constantinople. It is a hand-piano rather, of a loud and cheerful voice, whose Eurasian harmonies are enlivened by a frequent clash of bells.

What first made coffee-houses suspicious to those in authority, however, is their true resource—the advantages they offer for meeting one’s kind, for social converse and the contemplation of life. Hence it must be that they have so happy a tact for locality. They seek shade, pleasant corners, open squares, the prospect of water or wide landscapes. In Constantinople they enjoy an infinite choice of site, so huge is the extent of that city, so broken by hill and sea, so varied in its spectacle of life. The commonest type of city coffee-room looks out upon the passing world from under a grape-vine or a climbing wistaria”.

~H.G. Dwight. The Turkish coffee house. 1916.

“In the hours around sunset, I always find myself at the quay by Tophane, in front of a coffeehouse, sitting in the open air – it was an eastern tradition to watch people coming and going, to watch the night begin to fall… The divans lined up in the open air slowly fill with people of all races dressed in all the varied costumes of the East, without discrimination. The waiters seem rushed off their feet, rushing hither and thither as they serve little cups of coffee, rakı, sugar and leather cups containing the coals for the hookahs´ fire; the most leisurely hours of the evening are about to begin, the hookahs take flame and the air is filled with the lovely smell of smoke rising from golden yellow cigarettes.”

~ Pierre Loti, İstanbul

Street Coffee Seller, Istanbul, c1900. Istanbul’da Seyyar Kahveci.

“The common people’s coffee culture was simpler, were based around serving their neighborhoods,” says art historian Cicek Akçıl.

“Later, many kinds of coffee house appeared, such as tradesmen’s coffee houses, janissary coffee houses, and firemen’s coffee houses. There were also opium smokers’ coffee houses and public storytellers’ coffee houses, as well as coffee houses for aşıklar — the folk poets and musicians of Turkish oral culture.”

Not all coffeehouses had such spiritual functions, however, with some even operating as Constantinople’s, Istanbul’s first theaters. “Sometimes a barber would sit next to the coffee hearth so you could get a shave there as well,” Akçıl comments. “The janissary coffeehouses often had Greek dancers for entertainment and also attractive young boys serving the customers.”

A coffeehouse at the port:

Turkish Coffeehouse culture

“I like coffee houses. An old man has donned his spectacles. Another is furious about some customer who won´t give up the newspaper. Two old men are playing dominos, like kids. Three other people are wrapped up in some political discussion that would never even occur to you.

What a fuss people can make about some little item in the news that you wouldn´t even have noticed, honestly! Then, suddenly, you find yourself caught up listening to a man talking about how he would wipe out the black market. At first his ideas sound ridiculous. Later, you´ll tell yourself; That´s not such a bad idea after all.”

~ Sait Faik Abasıyanık, Kıraathaneler – Coffeehouses

Coffee and coffeehouse culture spread rapidly and soon became an integral part of Istanbul’s social culture. Many Muslim men visited the mosque for prayer up to six times each day, sometimes as little as two hours apart. As opposed to traveling home, they were able to reside in the coffeehouse until the next prayer time.

In addition to their entertainment function, Coffeehouses in Constantinople – Istanbul were a place to negotiate business and social deals, resolve conflict among family and neighbors, and forge friendships and alliances. Different social, economic, and denominational groups equally mingled in coffee houses.

In order to reside within the coffeehouse, customers needed to be able to afford a coffee. It follows that the grand coffeehouses, in an effort to support their more sophisticated interiors, charged more for the beverage and were thus inaccessible to those who could not afford it.

George Sandys, notes:

“Many of the Coffeemen keep beautiful boyes, who serve as stales to procure them customers. A perhaps clearer statement is that of a 16th century author (whose name is uncertain) of Risale fi ahkam al-kahwa; he mentions youths earmarked for the gratification of one’s lusts.

Other sources, including Arabic ones, are silent on this topic, although it may be included among the “abominable practices” that often go unitemised. It should also be noted that there was a certain vague connection between other low-life activities, some intermixing of actors and audiences was carried to its extreme, which greatly facilitated the formation of codes of belief, linking performance and society. By drawing spectators into action, engaging them in improvised scenes, and embodying role-exchange between audience and actor, Ottoman theater-coffeehouses had an influence on shaping the individual as a Public Man in the Sennettian sense.

These spaces served to produce publicity through theatricality and to shape the public sphere through theatrical expressions. Audiences were able to detach behavior with others from individual attributes of social or physical conditions and had made a move by this theatricality towards fashioning a sociable spatiality, out in Public, of which, such as gambling, are known to have been practiced in coffeehouses, and homosexual tendencies.”

Man came here throughout the day to read books, play chess, domino and backgammon, smoke and discuss poetry and literature.

Mèry states: “Coffeehouses also had their orators, whose eloquence found admiring patrons. The oriental orator [storytellers] was a poet, or a historian, who would tell fables or legends and land on every subject within the domain of imagination”.

With seating bordering the walls of the coffeehouse, the spacious center served as an unofficial stage for ordinary men to engage in creative self expression. There was no schedule and no famous performers; rather, sharing poetry grew organically out of the conversations transpiring within the coffeehouse.

Neighborhood coffeehouses served also as small public libraries, where mainly religious books and popular epics could be read and listened to. In fact, it is telling that the coffeehouse was also called Mekteb-i irfan, school of knowledge; or Medrese, academy of scholars. They were a “non-hierarchical sphere for cultural expression.”

The 17th century French traveler and writer Jean Chardin gave a lively description of the Persian coffeehouse scene:

“People engage in conversation, for it is there that news is communicated and where those interested in politics criticize the government in all freedom and without being fearful, since the government does not heed what the people say. Innocent games … resembling checkers, hopscotch, and chess, are played. In addition, mollas, dervishes, and poets take turns telling stories in verse or in prose. The narrations by the mollas and the dervishes are moral lessons, like our sermons, but it is not considered scandalous not to pay attention to them. No one is forced to give up his game or his conversation because of it. A molla will stand up in the middle, or at one end of the qahveh-khaneh, and begin to preach in a loud voice, or a dervish enters all of a sudden, and chastises the assembled on the vanity of the world and its material goods. It often happens that two or three people talk at the same time, one on one side, the other on the opposite, and sometimes one will be a preacher and the other a storyteller.”

Performances of traditional Turkish theatrical arts such as Shadow Puppetry (Karagöz), Classical Turkish Drama (Ortaoyunu), were first held at coffeehouses.

A tradition of Turkish folklore that also took shape in Constantinople’s coffeehouses is the Meddah, which sees a storyteller performing in front of the audience of the coffee shop, interpreting various dramatic or comedic roles, changing each time the tone of voice and helping himself with a cane or a handkerchief to indicate the change of scene or character. The art of Meddah was included in 2003 among the oral and intangible heritage recognized by UNESCO.

The artists were traveling from town to town, entertaining the patrons of the cafes with their stories: Constantinople, today’s Istanbul, capital of the Byzantine Empire before and now international metropolis in Turkey, continues this wonderful tradition, made of coffee and stories.

Coffee shops throughout the Arab world were the arena of intellectual and artistic creativity in following centuries. Vehement discussions took place regularly among poets, writers, journalists and intellectuals who held circles in a designated area of the café, attracting curious and knowledge-thirsty listeners. Literary masterpieces were created in coffee houses by renowned national or pan-Arab writers. The famous Egyptian writer and Nobel Prize winner, Najib Mahfouz, was frequently seen sipping coffee and writing in Cairene cafés.

The influence of cafés further extended into politics. Some of these cafés were the main meeting place for activists and national liberation movements across the Arab world in the first half of the twentieth century. Political parties used to convene in cafés to organize actions such as strikes, demonstrations, and election campaigns.

The only thing being read in coffee- and tea houses now are daily papers, and in most places phones, radio and televisions have replaced papers. Passionate conversations, arguments about politics and social matters still take place at coffee- and tea houses and they are still places where people “save” the country and the world, and moreover, where the tension of the public is measured.

Maybe coffee houses in Istanbul lost their importance today, but coffee and tea remains a central and popular drink in many different places, whether in restaurants, clubs, theaters, universities, salons and most importantly inside homes.

“Hoca Kadri Efendi, a member of the Young Turk movement, spent his whole day at this coffeehouse [La Closerie des Lilas in France]. The poet Yahya Kemal Beyatlı used to say that he was a regular at that coffeehouse for 9 years during his student days. According to the metal plates on the tables, Lord Byron, Anatole France, André Gide and Lenin were also regulars. Yahya Kemal met a pre-revolutionary Lenin in this coffeehouse.”

~ Taha Toros, Kahvenin Öyküsü, The Story of Coffee. THANK YOU

Mehmed Efendi Mandabatmaz

Mehmed Efendi of Kemah opened his coffee shop that sold ground or roasted coffee in 1871 in Tahtakale. Several coffee vendors set up shop on Tahtakale’s Tahmis Sokak, which means “Roasted and Ground Coffee Street.”

Coffee here is still served

“so thick even a water buffalo cannot sink in it”.

Mandabatmaz, meaning – the buffalo will not sink – because is known for its thick, intense coffee foam.

Traditionally people were drinking Türk Kahvesi without any sugar, unsweetened coffee is called “country style” or “man’s coffee”, till today.

Among the people, coffee was named according to its density, the amount of sugar it contained or the cup in which it was served. Whether the coffee was roasted or not was also important. The more the coffee is roasted, the more it loses its acidic features.

Nowadays, Turkish coffee is made after asking the guests how much sugar they prefer:

- şekerli sweet

- orta şekerli medium sweet

- az şekerli a little sugar

- sade which means no sugar

Turkish coffee, Türk Kahvesi is incredibly thick and dense. It is not unusual to hear the local people describe the beverage as: “black as hell, as strong as death, and as sweet as love”.

Kahve, lütfen, – to Suleiman the Magnificent, I think, holding up my coffee cup in a toast.

“Thanks for the Türk Kahvesi.”

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

The history of coffee is an extraordinary study. If you would like to learn more about it, we heartily recommend the book, All About Coffee, by William Ukers. Written in 1928, it is as good a book on coffee as has been written and will delight you with detail. Also the new book Short History of Coffee, by Kerr Gordon is delightful.

Thank you Klaus for proofreading and sharing your knowledge about culture in Turkey.

- Baum Emily. Ottoman Women in Public Urban Spaces. 2012.

- Chamberlayne John. The Natural History of Coffee, Thee, Chocolate, Tobacco: Collected from the Writings of the Best Physicians and Travelers.1682.

- Çizakça Defne. Long Nights in Coffeehouses: Ottoman Storytelling in its Urban Locales.

- Coffee in Istanbul. Mehmet Efendi.

- Coffeehouse.

- Dwight, H. G. Stamboul nights. 1916.

- Ervin Marita. Coffee and the Ottoman Social Sphere. Student Research and Creative Works. 2014.

- Events Key. The Story of the Coffee House.

- From Kaffa to Istanbul: Coffee’s journey to Turkey.

- Kucukkomurler Saime, Ozgen Leyla. Coffee and Turkish Coffee Culture. Article in Pakistan Journal of Nutrition. 2009.

- Lee Stewart Allen. Devil’s Cup. A History of the World According to Coffee. 1999.

- Meddah – Story Teller

- Nair Sharmila. Turkish coffee, a 500-year-old tradition.In: Food News. 2015.

- Pendergrast Mark. Uncommon Grounds: The History of Coffee and How It Transformed Our World. 1999.

- Sansal Burak. Turkish coffee. All About Turkey.

- The Mythology and Origins of Coffee.

- The Story of Coffee.

- The Turkish Coffee Culture and Research Association.

- Turkish coffee culture and tradition. UNESCO.

- Ugur Kömeçoglu. The publicness and sociabilities of the Ottoman Coffeehouse. 2015.

- Ukers W. H. All About Coffee. The tea and coffee trade journal.1922.

- Wild Anthony. Black Gold: A Dark History of Coffee. 2005.

- Wilson Georgia. Drinkable history: the 500-year-old method to making coffee. 2014.

- Wikimedia for Illustrations.

- https://www.tastingtable.com/1029221/times-coffee-was-banned-around-the-world/