Violeta Parra was a folklorist and an ethnomusicologist, a poet, a musician, a painter, a sculptor and a tapestry maker. Above all, however, her work captured Chile’s history, its culture, and its pain.

In this Article

I found myself sipping a mate and talking about music with a Chilean son and mother couple. Maria says: ”Somos esclavos que conocemos el miedo- we are slaves that know fear. I grow up in fear and learned to be scared, during the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet – the only thing that remained was to sing- and that was dangerous too.”

Her son Fabiano takes out the guitar and they start with a melancholic, yet soft voice:

"Thanks to life, which has given me so much He gave me the laughter and gave me tears Thus I distinguish happiness from brokenness The two materials that form my song And the song of you that is the same song And the song of all that is my own song Thanks to life, thanks to life."

This is one of the most famous Chilean songs and “Gracias a la vida” has been used as an hymn of social movements across the world. It was released in 1966, as part of the last album Violeta Parra recorded. Along with many of Violeta Parra’s songs, “Gracias a la Vida” was banned during the repressive dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet from 1974 to 1990. I knew that song through Mercedes Sosa and Joan Baez, Violeta was great storyteller using folk music and folk art to tell stories about her life and about Chiles folk.

Violeta Parra Sandoval- The daughter

Violeta Parra was born in San Fabián de Alico, or in San Carlos, small towns in the Ñuble Province of southern Chile on 4 October 1917, as Violeta del Carmen Parra Sandoval. As I stand in front of her monument in the public square, called plaza de armas in San Carlos, I can not but think about Pablo Neruda’s words:

“Santa Violeta, tú te convertiste en guitarra con hojas que relucen al brillo de la luna en ciruela salvaje, transformada, en pueblo verdadero.”

Holy Violeta, you became, at the guitar with shining leaves, in the brightness of the moon, a wild plum, transformed, into the true folk. [my translation]

As Sergio Reyes writes in Remembering Violeta Parra:

Violeta was ten years old, as 1927 fear came to Chile as Carlos Ibañez del Campo was elected president. His administration evolved into a virtual dictatorship. In an effort to recover the ailing economy to benefit both foreign and domestic capitalists, Ibañez unleashed a ferocious wave of repression against every kind of opponent. Ibañez handed Chilean resources over to American capitalists, including the copper mines and the telecommunications industry. Violeta’s father shared the fate of thousands of teachers who where fired for political reasons. As refuge from his misfortune, he turned to songs, the guitar and wine.

The dictatorship this devil practiced was so cruel that teachers throughout the country could no longer function. There were penalties all over penalties for trash penalties for walking at night penalties for quietness or noisiness […]

Her father, desperate from unemployment, is said to have found refuge in alcohol. Violeta Parra Sandoval completed her primary studies but later abandoned them for work. To help her family’s income, she began to sing in trains, small towns, restaurants and circuses. After her father’s death, Violeta in 1932, followed her brother Nicanor to the capital of Santiago, where she performed in nightclubs and bars. With her sister she formed The Parra Sisters a folkloric musical duet. The boleros, corridos, cuecas, rancheras and tonadas would be the means that would lead her to discover her own voice.

She married 1938 and gave birth to Isabel and Angel, both inheritors of her musical tradition.

That same year the progressive administration of Pedro Aguirre Cerda came to power. Violeta contributes to government policies to limit price increases by setting up a food distribution center in her home.

In 1948, after ten years of marriage, Parra and Luis Cereceda separated. The following year she remarried Luis Arce. From this new marriage two girls were born. Violeta Parra continued performing: she appeared in circuses and toured, with Hilda and with her children, throughout Argentina.

Violeta Parra- The Folklorist and Ethnomusicologist

During the 1950s, Parra embarked on the arduous journey of traveling across the vast Chilean landscape, in research of folklore. As an Ethnomusicologist she approached music as a social process in order to understand not only what music is but why it is: what music means to its practitioners and audiences, and how those meanings are conveyed.

She travelled to the central valleys interviewing, recording, writing, and memorizing old folk songs, stories and poems, her collection amounted over 3000.

The bulk of her research was summed up in her book “Cantos Fokloricos Chilenos.”

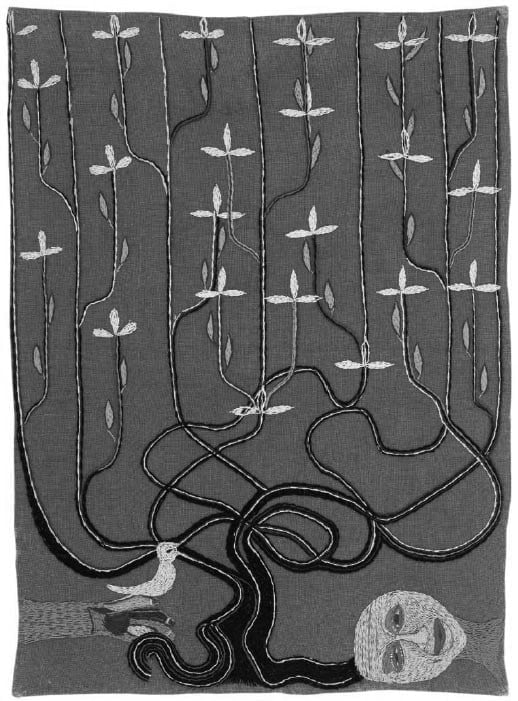

It was at this time that her interests began to branch out into other fields – she began to try her hand at painting, arpillera embroidery, and ceramics.

Songs about miners

About the miners she wrote “Arriba quemando el sol”– And overhead, the sun burning down:

And overhead, the sun burning down. When I saw how the miners lived I said to myself The snail lives better in his shell And so do the most sophisticated thieves In the shade of the Law. Arriba quemando el sol

In her voyages, Parra was able to recover songs like “El Sacristan” and “El Palomo” and grasp the marginalization of Chile’s rural communities and deep-seated class differences that divided the country. Through her songwriting, Parra tackled every aspect of Chilean public and private life – the unjust treatment of miners, the hypocrisy of the Catholic Church, the struggles of indigenous Mapuche communities, as well as the drama of her own personal relationships.

Songs about the Mapuche communities

In “Arauco Tiene Una Pena,” Parra exercises sociopolitical commentary by singing about the indigenous populations of Chile — particularly the Mapuche who inhabit the region of Arauco.

La Viola grieves the oppression of the Mapuche who were first exploited by Spanish Conquistadores and now confront similar marginalization at the hands of the Chilean population at large.

Arauco has a sorry That I cannot quiet They are injustices of centuries Which everyone sees imposed, Nobody has remedied it. […]

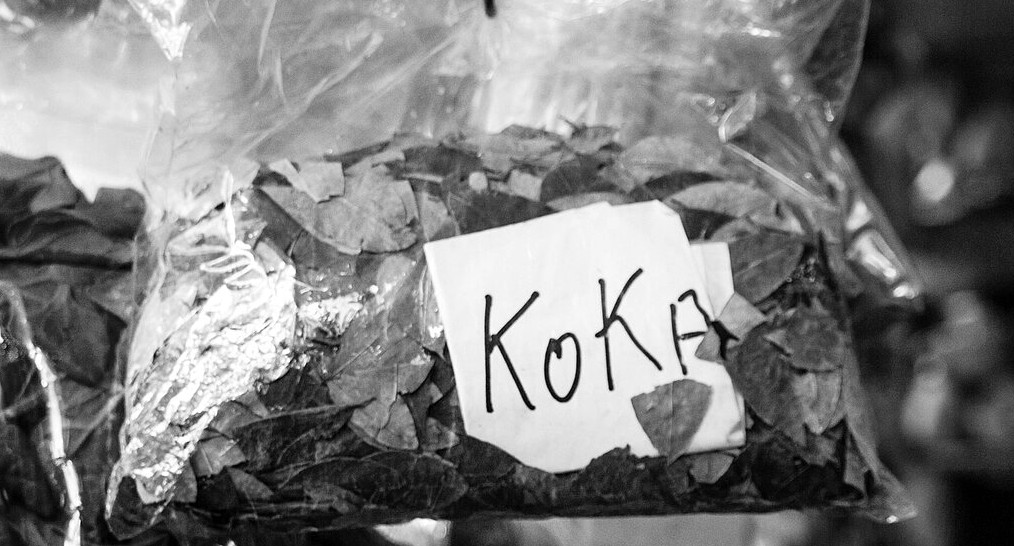

The name Mapuche means “people of the earth.” The autumn harvest usually comes in March and for the Mapuche, this is a time to say special prayers to give thanks and ask for fertility and protection from floods, droughts, and other disasters.

A special nguillatun (gee-ya-TOON), or prayer ceremony, is held at harvest time and is led by a machi, a religious leader who is usually a woman. People apply blue and white paint to their faces—colors which are considered spiritually positive. For two to four days the Mapuche pray, sing, dance, make animal sacrifices and feast.

Violeta Parra describes this ritual in “El Guillatún:”

She was very important in recovering forgotten and lost Chilean traditional music, which she kind of reshaped. In “Yo Canto a La Diferencia,” Parra declares that she doesn’t make music for fame or praise, but to expose what’s right and what’s wrong.

[…] no tomo la guitarra Por conseguir un aplauso Yo canto las diferencias que hay de lo cierto a lo falso De lo contrario no canto

She offered concerts and readings throughout Chile. In 1953 after such a concert and reading in PabloNeruda’s house the Chilean Radio offered Violeta a number of programmes so that she could broaden her listening audience into thousands of homes. So her original and preserved songs reached a wider audience through the “Canta Violeta Parra” radio programme that ran from 1953-1954 on a leftist radio station. She also ran La Peña de los Parra, a performance space and community centre.

Entró Violeta Parrón violeteando la guitarra guitarreando el guittarón entro Violeta Parra.

Violeta’s name Parra in Spanish means ´grapevine´an image that prompted PabloNeruda to write of Violeta

Parra you are, and sad wine you will become.

Violeta Parra led a tumultuous life. She travelled throughout Europe and the Soviet Union, and settled in Paris, where she recorded several albums.

Testimony of her husband, Jorge Arce:

“It was 28 days since Violeta had left Chile when our Rosita Clara died. Somebody sent her a letter about it, but it seems they didn’t explain her exactly what happened, so she thought it was all my fault… Since then I received two letters a week where she systematically blamed me for our daughter’s death. Later on she learned the truth — our baby had died of pneumonia.”

When I left this place

I left my baby in her crib hoping our nanny the moon was going to take care of her but it wasn't like that a letter would reveal to me breaking my heart to pieces that I would never see her again the world is a witness that I will pay for this sin.

Following the sudden death of her youngest daughter; Rosa Cara she returned to Chile where she accepted a post at the University of Concepción, directing the Museum of Popular Art, and continuing with her performing, songwriting, research, and crafts, including painting, arpillera embroidery- tapestries, sculpture and ceramics. She went on to record more albums. And travelled to Argentina and Chiloe, South Chile.

La Viola- Mother of the Nueva Canción

To get to know a people it is to know its music in its cultural context.

The Nueva Canción movement of Chile was established by la Viola, as she was called by her friends, in the early 60s; her Andean-infused folk songs were highly political and nationalistic in their lyrical as well as melodic content.

The most important source for Nueva Canción is the recollection and diffusion of folklore undertaken independently by Violeta Parra and Margot Loyola in the 1950s and 1960s.

Parra’s music constantly confronted the harsh political realities that existed in Chile years before Pinochet’s infamous dictatorship. Songs such as “Hace Falta un Guerrillero” -It Takes a Guerrilla and “La Carta” -The Letter, are full of anti-government sentiments, reflecting solidarity among Latin Americans and their socialist feelings. While in Paris, she received a letter informing her that her brother Roberto had been detained after the Jose Maria Caro massacre, during the government of Jorge Alessandri. This sorrowing response to the arrest of her brother Roberto for supporting a strike was released posthumously from “La Carta”:

I am so far away Waiting for news The letter comes to me That in my country there is no justice The hungry are asking for bread The militia give them bullets, yes.

sings out Parra as she echoes the social injustices prevalent in Chile due to the foreign demand for the country’s resources and the control over resources by foreign investors. By this time, all throughout Latin America, but especially in Chile, the New Song Movement began to take shape. This movement denounced the unfair and miserable living conditions of the working class and supported the struggle for liberation from capitalist exploitation.

New Song musicians like Quilapayún, Inti- Illimani, Rolando Alarcón, Patricio Manns and Victor Jara entered the airwaves by popular demand.

Victor Jara

In 1957 she met with folksinger Victor Jara and inspired the young artist to join the movement. Both artists strongly supported Salvador Allende’s early bids for the Chilean presidency, and Parra maintained ties with members of Chile’s socialist and communist parties.

Soon, Jara would become an active part of the Nueva Canción movement, performing songs that spoke passionately about controversial topics of the day such as imperialism, poverty, religion and human rights.

Allende was elected president of Chile in 1970 – a time when music of the Nueva Canción was at its most rampant. However, in 1973, Chilean right-wing leaders rallied a coup d’état with the help of the Chilean military. In 1973, Jara was on his way to teach at the Technical University, now known as University de Santiago. As a protest, all students, along with Jara, stayed at the University over night. However, in the morning, Jara, as well as thousands of others were taken to the Chile Stadium (renamed the Estadio Victor Jara in 2003), where they were tortured for several days. Jara, known widely by then as a cultural as well as political-activist against Pinochet’s right-wing regime, was repeatedly battered and humiliated. The bones in his hands were broken and soldiers ridiculed him as he could not play his guitar any longer.

Defiantly, he sang part of “Venceremos” – We Will Win, a song supporting the Popular Unity coalition.

An officer played Russian roulette with Jara, repeating this a couple of times, until a shot fired and Jara fell to the ground. The officer then ordered two conscripts to finish the job by firing into his body. Jara’s body was dumped on a road on the outskirts of Santiago and then taken to a city morgue where 44 bullets were found in his body.

Before his death, Jara wrote a poem about the conditions of the prisoners in the stadium, it was written on paper that was hidden inside a shoe of a friend. The text was never named, but is commonly known as “Estadio Chile”:

The fate of Nueva Canción changed abruptly with the military junta. The Commander in Chief of the Army, General Augusto Pinochet was appointed head of the junta, and in late 1974 declared President of Chile. Pinochet’s rule of Chile lasted for sixteen and one-half years, and was notoriously involved in brutal human rights violations, including killings, disappearances, imprisonment, torture, and exile of political opponents. In the direct aftermath of the coup, any person who had been involved in Allende’s government was considered a political opponent and was at risk. Because Nueva Canción had played such a highly visible role in Salvador Allende’s campaign and presidency, its members became an immediate target of the regime’s repression. As Nancy Morris recounts, Nueva Canción

“was banned from the airwaves, removed from record stores, confiscated, and burned along with books and other ‘subversive’ material during the house-to-house searches that immediately followed the coup”

Ángel, Violettas son would also become a political prisoner at the National Stadium in Santiago and at Chacabuco concentration camp in the Atacama Desert, during the brutal, coercive civic-military dictatorship led by General Augusto Pinochet.

Violetas songs during Pinochet’s dictatorship

As Katia Chornik points out:

Violeta Parra’s songs were present in Pinochet’s political detention centres and used by prisoners and guards in various ways, as seen in testimonies.

Run Run se fue p’al norte -Run Run Went Up North was sung at the National Stadium to inmates who were about to be transferred to Chacabuco concentration camp.

Qué dirá el Santo Padre -What Will the Holy Father Say was sung at La Serena’s Buen Pastor (run by Catholic nuns) when prisoners were taken to a torture centre.

Volver a los diecisiete -To Be Seventeen Again was used at Santiago’s Cuartel Borgoño to humiliate a tortured detainee.

And Pa cantar de un improviso -To Sing by Improvising inspired prisoners held at Puchuncaví concentration camp to build musical instruments.

Violeta- The Lover

Having divorced Arce in 1955, she met the young Swiss flutist Gilbert Favre in 1960, on the day of her 43rd birthday. Favre had come to the Atacama desert as part of an anthropological expedition, which he promptly abandoned in order to live with Parra in Santiago, Paris, and Geneva.

It was about this time that her songs took a more complex path, becoming more political and philosophical. Like “Corazón Maldito”, “El Gavilán” and “Qué he sacado con quererte” and “Run se fue por il norte.”

El Gavilan (The Chicken-Hawk)

Run Run Se Fue Pa’l Norte’ (Run Run, He’s Left for the North) explores the grief that manifests itself after a loss and the way our hearts continue to travel with those who are already long gone.

During the dictatorship that forced at least 20,000 Chileans into exile, the song took on another meaning, especially for all those who were separated from their loved ones, many of them in northern countries.

On a car made of oblivion, Before dawn broke, On a transit station, Resolved to keep rolling Run run, north he went.

Violetta Parra- The Visual Artist

Her visual work, paintings, sculptures and tapestries, often inspired by folk traditions, was created in Santiago, Buenos Aires, Paris and Geneva between 1954 and 1965. Back to France, this time in the company of her children Angel and Isabel, in 1964 the Louvre of Paris presented an exhibit of her “arpilleras” tapestries, painting and wire sculptures – the first solo exhibition of a Latin American artist at the museum.

In 1965, the publisher François Maspero, Paris, published her book Poésie Populaire des Andes. In Geneva, Swiss television made a documentary about the artist and her work, Violeta Parra, Chilean Embroiderer.

Testimony of her daughter Carmen Luisa:

“The only time I went in the coffee houses where my mother worked was when my mother was in France for the second time. I remember when she sent for me: It was a terrible trip because I ended up in the wrong airport and, of course, there wasn’t anybody waiting for me. She had already been there for three months and was very sad about our separation, so as soon as she had enough money she bought me tickets. There she was awaiting me with a new song, “Absent Dove.” With all the tension of the airport mix-up our encounter was so emotional: she hugged me a hundred times, crying and asking a thousand questions, and in between all this she sang the song she had composed for me.”

Five nights in a row, I cry for you. Five handwritten letters the wind blew away. Five black handkerchieves have been witness To the five pains growing in me. My absent dove, white dove, a rose in bloom.

In 1964 Angel and Isabel returned to Santiago and opened the famous “Pena de los Parra”. Many of Chile’s best known composers began playing at La Pena, including Quilapayun and VictorJara. Today, “La Pena de los Parras” is home to the Violeta Parra Foundation.

La carpa de la Violeta

Back in Chile, Violeta Parra created La Carpa in the neighborhood of la Reina, the performance/cultural space outside of Santiago. Located on donated land beyond the bus lines, it had been Parra’s hope that La Carpa would be a place to create the contemporary and future cultural lifeways of campesinos and the working class with whom she identified. Since it could only be arrived at by taxi or private cars, however, its audiences tended to be of the wealthier classes or tourists, when people came at all.

Boyle writes in Violetta Parra: Life and Work. 2017:

“Rather than being a place of community, it became in part what Violeta loathed most-a place for a social event, a ‘noche de gala’, a point on the tourist itinerary…and for a lot of intellectuals”.

This final, doomed, project exemplifies the tragedy of Parra’s contradictions and loneliness, as well as her surety of vision, creativity, energy, and hope. Her relationship with Gilbert Favre expired when the anthropologist decided to leave for Bolivia in 1966, and Violeta would be left deeply depressed.

In a convulsed country that anticipated a political transformation into dictatorship and repression, her dream didn’t come true and the public did not support it. However, on February 5th, 1967, Violeta stopped singing forever.

Testimony of her daughter Cármen Luisa:

“I was tidying up in the tent, it was around six p.m. and suddenly I heard a shot… I run into my mother’s bedroom and there I found her, laying on her guitar, holding a shotgun. I talked to her, moved her, but she didn’t answer. Then I realized that blood was dripping from her mouth. I was shocked and paralyzed; don’t know why but my first reaction was to take the shotgun from her hand. Then I went out and cried out for help. The tent was soon full of people, the police… an ambulance took her away.”

In 2014, Museo Violeta Parra was founded by the artist’s children Angel and Isabel Parra, in Santiago, Chile in order to preserve and share her work and legacy.

From ‘Defensa de Violeta Parra’, by her brother, anti-poet Nicanor Parra.

Sweet neighbor of the green wood Eternal guest of flowering April days Great enemy of the bramble Violeta Parra. Gardener Potter Seamstress Dancer of the crystal clear water Tree brimming with singing birds: Violeta Parra.

…Love is a whirlwind of original purity, even the fierce animal whispers its sweet trill, stops the pilgrims, and liberates the prisoners, love with its best efforts turns the old into a child and only affection can turn the bad pure and sincere…

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- Chornik Katia. Violeta Parra and the birth of ‘New Song’. History Extra. https://www.historyextra.com/period/20th-century/violeta-parra-and-the-birth-of-new-song/

- Cunningham Amy. Victor Jara – The martyred musician of Nueva Canción Chilena. 2011. https://soundsandcolours.com/articles/chile/victor-jara-the-martyred-musician-of-nueva-cancion-chilena-11063/

- Habib Yamily.Who was Violeta Parra? Al día daily. 2017.

- Illiano Roberto. Sala Massimiliano. Beyond ‘Protest Song’: Popular Music in Pinochet’s Chile (1973-1990). In: Music and Dictatorship in Europe and Latin America. 2010.

- Mendez Joshua A. Top 10 songs by Violeta Parra that you need to know. 2016. https://soundsandcolours.com/articles/chile/top-10-songs-by-violeta-parra-that-you-need-to-know-30979/

- Museo Violeta Parra http://museovioletaparra.cl/

- Prologue of The Restless Life: Essential biography of Violeta Parra [La vida intranquila: Biografía esencial de Violeta Parra, Planeta Chile, 2017] by Fernando Sáez. http://www.ventanalatina.co.uk/2017/07/violeta-parra-fernando-saez/

- Review of Violetta Parra: Life and Work. Edited by Lorna Dillon. 2017. http://www.indiana.edu

- Reyes Sergio. Remembering Violeta Parra. http://www.avizora.com/publicaciones/biografias/textos/textos_p/0036_parra_violeta.htm

- Saez Cristóbal. Iconográfica: A Tribute to Folk Icon Violeta Parra, the Rebel Heart of Chile. http://remezcla.com/features/music/iconografica-violeta-parra/

- Valdivieso Marci. The Centennial of Violeta Parra in Berkeley. 2017. http://radiobilingue.org/en/features/el-centenario-de-violeta-parra-en-berkeley/

- Violeta Parra Foundation http://www.fundacionvioletaparra.org/.

- Wednesday’s Wise Woman … Violeta Para. 2012. https://nelabligh.com/2012/08/22/wednesdays-wise-woman-violeta-para