For the Incas, as well as for today’s Aymara and Quechua farmers of the Andes, the potato is more then sustenance, it is a symbol, a protective spirit, and saved legendary people from slavery. Discover history and folklore of the potato – papa 🥔, in Andean culture.

In this Article

History: The potato and the Andean people

Growing wild as early as 13.000 years ago on the coast of South America, and some possibly much older, at the Monte Verde archaeological site in southern Chile. Andean peoples domesticated wild potato varieties as far back as roughly 10.000 to 8000 years ago.

The high mountains (Altiplano) of what is Bolivia and Peru today, and specifically the high plateau region around Lake Titicaca (~12,000 feet or 3657.6 m, elevation and higher) may have been where they were first selectively cultivated.

Archeological record of potatoes from ancient Peru and Bolivia

Archaeological findings suggest that domestication may have occurred in the humid lowlands of southern Chile, as well as in the cold high Andes.

One of the earliest archaeologically verified potato and sweet potato remains, dating to the Neolithic Period (and perhaps to the end of the last Ice Age, or 8000 BC), were discovered in caverns at Chilca Canyon, in the south- central area of coastal Peru.

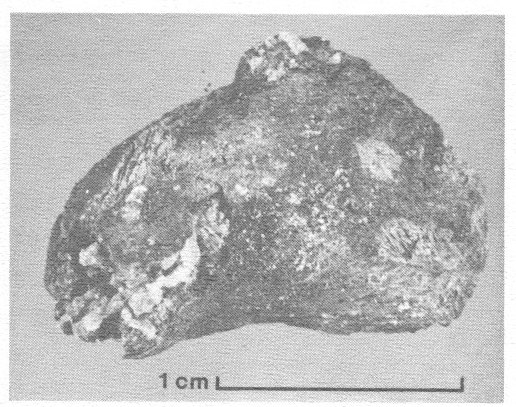

A 3500-year-old potato tuber from Pampa de las LIamas-Moxeke in the Casma Valley, Peru.

As seen in the lower left-hand corner of the photograph, a portion of the dried cortex has been exposed as a result of natural shrinkage and breakage of the tuber skin.

Salt crystals have also accumulated in the other broken areas and lesions of the skin. Internally, the starchy cortex remains in near perfect condition.

Archaeological discoveries from Andean Bolivia and Peru include pottery on which the potato is depicted. Various ceramic vessels were used in religious ceremonies and funeral rites in these Andean regions of South America.

Pottery, filled with different foods, were also placed in graves along with the dead. Occasionally, these vases portrayed human figures, but nevertheless with the characteristics of potato tubers such as eyes and knobs.

Incan potato cultivation

With the Incan civilization (Ca. 1200–1530 CE) the tuber’s true agricultural potential was realized, after learning from earlier cultures. The Inca wisely prized agricultural diversity, growing over 3000 varieties of potatoes in various sizes, textures and colors.

In Moray, farmers experimented with different potatoes in terraced circles. Their goal was to develop a different kind of potato for every type of soil, the sun, and moisture condition. Part of the reason is practical; farming in mountainous regions presents tremendous challenges.

Conditions change dramatically with elevation. The ocean side of the mountains tends to be wet, and the inland side dry. Temperature and moisture can vary substantially just from one side of a valley to another. This encouraged growing large numbers of varieties with different tolerances and resistances to hedge against changing conditions.

Equally, the appreciation of form and color in foods appears to be a cultural value. This could be in part because it makes varieties recognizable so that those with useful traits can be easily identified and remembered, but it also appears to be a consistent motif in many areas of traditional Andean cultures. There are at least 2000 varieties of Andean potatoes and individual farmers may grow as many as 200 different varieties in a single field (NRC 1989).

The Incas were masters of plant domestication, especially potatoes. Their development of the potato was remarkable: from 8 species of weeds having toxic tubers to more than 3000 distinct potato varieties. Inca communities pioneered a seven-year potato crop rotation to prevent decimation by a nematode pest whose life cycle was of six years.

The potato figures prominently in folklore and recorded post conquest stories of the Aymara and Quechua.

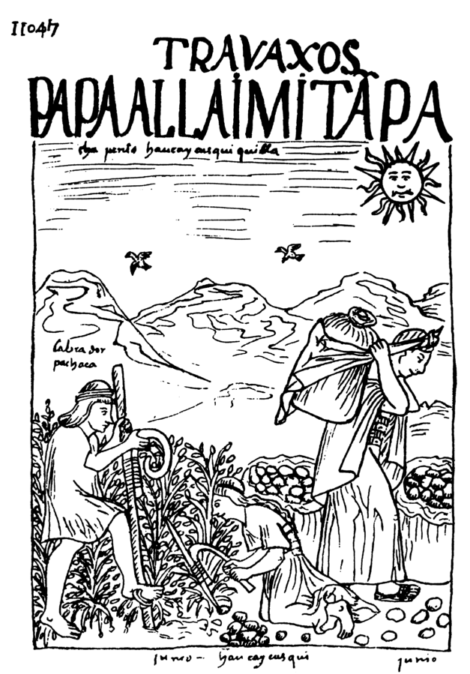

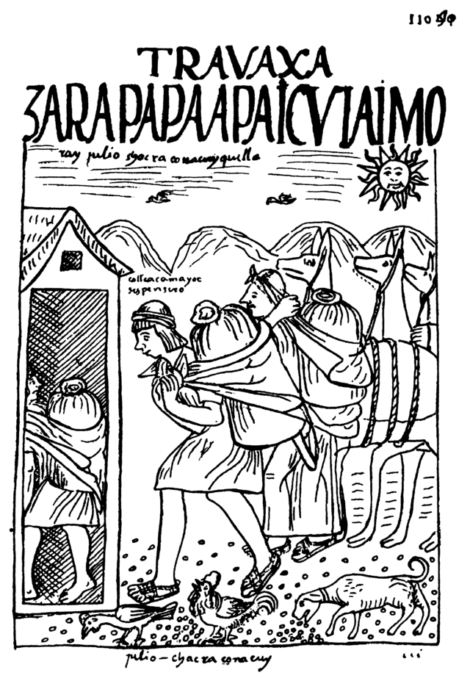

p. 1147. June: PAPA ALLAI MITAN PACHA. Time of digging up the potatoes. Guamán Poma de Ayala, Felipe, 1615. Nueva corónica y buen gobierno. Public domain

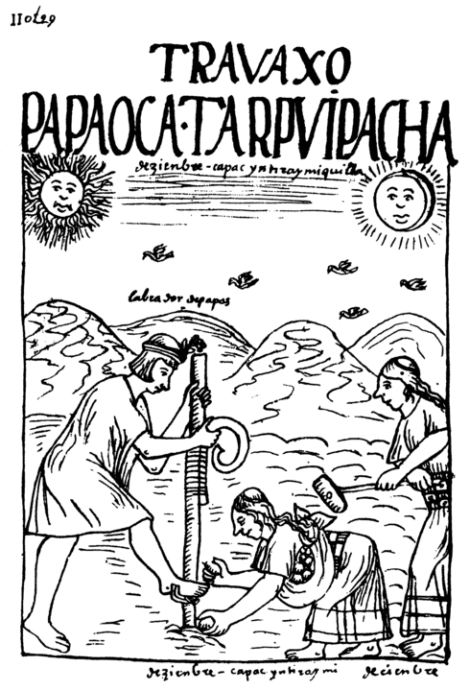

The images depict indigenous Quechua people using taclas and ayachos during a potato planting in the year’s early summer months and harvest towards winter. Both male and female planters are working the fields. Potato planting and harvesting was a duty for all, as the more people contributing would create a greater yield (Ayala).

Potatoes were stored in underground warehouses called qullqas, along with other products, like coca, quinoa and maize. This storage was crucial for ensuring food supply throughout the year.

The potato joined corn (maize) and quinoa as one of the Incan “three sisters” of complementary crops and staple foods. Along with a rich source of protein, the cuy (guinea pig). Incas also traded potatoes with neighboring tribes and regions, establishing the tuber as a valuable commodity in their extensive road network.

Freeze-dry potatoes, Chuño, can be combined with other vegetables and meat in stews and ground for use as flour. It became an important item that highland people traded for products from lower elevation regions. Chuño was a light and easily transported staple food for the thousands of soldiers in Incan armies.

Papa, coca and maize, were used as offerings in religious ceremonies and rituals, and they revered this plants and buried them with their dead.

Today, the potato plays an important role in Quechua cultural traditions. In many communities, if a man wants to marry a woman, the man’s mother presents her with a potato named for its ability to “make the daughter-in-law cry.”

The daughter-in-law must carefully peel the knobby tuber, which resembles a pine cone in shape. If she removes more than is necessary, she will not be allowed to marry the woman’s son.

The ceremony surrounding potato planting and harvesting is another cultural pillar in Andean Quechua communities. These rituals are a traditional way of showing respect to the Earth Mother (Pachamama) and to the crops that sustain these people, they almost always involve an offering on coca leaves.

This ceremony, called quintu, involves multiple sets of three coca leaves, which are combined with llama fat and placed into the first hole where potatoes are to be planted.

Andean communities continue to cultivate their land in a manner essentially unchanged from that of their ancestors, while economic and market factors pull farmers away from diversity and towards cash crops.

Papamama or Axomamma

In the ancient ruins of what is today Bolivia, Peru and Chile, archaeologists have found remains and pottery on which the potato is depicted. These ceramic vessels were used in religious ceremonies and funeral rites in these Andean regions of South America.

Incas believed that each crop had a protective spirit named Conopas. This spirits were the best proceeds of the crop which was set aside in order to offer it to the gods during a special ceremony. They believed that the offering would maximize their yields.

For instance, the Conopa of maize would be called Saramama (mother of the maize), of potato, Papamama, of coca, Cocamama or Mamacacao. There is another Papamama, called Axomamma (also Acsumama and Ajomama), she is the goddess of potatoes in Inca mythology and one of the daughters of Pachamama, the Earth mother.

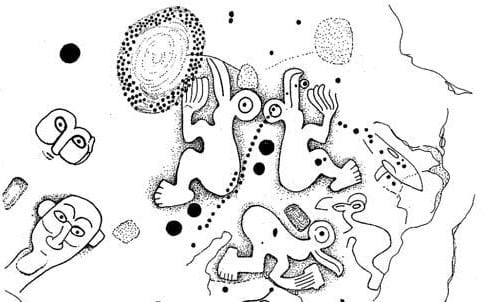

Potatoes and other food plants, such as maize and peanuts (of tropical South American origin) were sometimes combined with human beings by the Mochica or Moche (100 CE – 700 CE) potters, as in the picture of the Potato Woman or the Potato Mother.

Here the “eyes” are represented as human faces, possibly a supernatural connection reflecting mythological origins of the plants.

Potatoes form a vital part of the food supply of the Incan people, and most villages would have a particularly shaped potato to worship and ask for a good harvest. The Andean people grew, ate and also worshiped the tuber:

“O Creator! Thou who givest life to all things and hast made men that they may live, and multiply.

Multiply also the fruits of the earth, the potatoes and other food that thou hast made, that men may not suffer from hunger and misery.”

Inca prayer

They buried potatoes with their dead, stashed potatoes in concealed bins for use in case of war or famine, dried them as chuño and carried them on long journeys to be eaten on the way.

Chuño

Guamán Poma de Ayala, Felipe, 1615. Nueva corónica y buen gobierno. Peruvian manuscript. Public domain.

There is evidence, that the Inca knew how to freeze-dry potatoes. At night, the cold of the Andes froze the tubers. (Raw potatoes are 80 percent water.) During the day, however, they thawed in the warmth of the sun.

As they defrosted, laborers stamped on them to press out all the moisture. After several days of alternating freezing and defrosting, the potatoes were dehydrated and transformed into a lightweight, transportable dry papa known as chuño.

Stored in sealed, permanently frozen underground storehouses, the freeze-dried potatoes kept for five to six years. When needed for sustenance during the lean months, the chuño could be reconstituted by soaking in water, then being cooked or ground into meal, with no loss of nutritional value.

Chuño was so precious to the Inca that it was used as currency and collected as tribute.

Chuño negro

The Black Chuño, or simply Chuño, is obtained directly from freezing, treading and re-freezing. The process works without water, it is dehydrated by pressing it against the floor with the feet (squeezing), then the frozen tuber dries in the sun. Certain substances will oxidize, in contact with air, giving it a characteristic color that goes from dark brown to black.

Tunta, moraya o Chuño blanco

Tunta is obtained by freezing the potato for a night outdoors in winter frost (June-July), the next day it is dehydrated by pressing it with the feet against the floor (squeezing) and put into river water or in a lagoon in permeable plastic bags. This procedure is done after sun set to keep the white color. The potatoes are usually light color, but on contact with the sun rays they get black.

Marco Gozzo tells the story of “The Vanishing Aymara Potato Tradition” (short movie)

The history of potatoes, Solanum tuberosum, is rooted in South America, there are more than 4.000 varieties of native potatoes grow in the Andean highlands of Peru, Boliva and Ecuador.

The discovery of potato was ever a story of many dimensions, and the telling of the tale depended on the use as medicine, food, or drink. Papa joined corn and quinoa as one of the Incan “three sisters” of complementary crops and staple foods and the cuy (guinea pig), as a rich source of protein. Due to the importance in daily life in the Altiplano, it was intimately related to deities, demi gods, and mortals.

LEGEND: On how the potato came to Bolivia

Como la papa llegó a Bolivia

Como la papa llegó a Bolivia

Hace mucho tiempo, el pueblo de los Sapallas tenia una existencia pacífica y armoniosa. La naturaleza generosa proporcionaba enteramente a las necesidades de cada uno, y la Entente Cordial con los países vecinos les había hecho olvidar lo que era la violencia y la guerra. Un día, la erupción súbita de un volcán vino a perturbar la armonía de este pequeño mundo al parecer perfecto. Los Karis vecinos de los Sapallas, que vivían al norte no lejos de los lados del volcán, tuvieron que huir de su país devastado y abandonar la mayoría de sus bienes. Atraídos naturalmente por las riquezas del territorio Sapallas, los Karis tomaron las armas e invadieron por la fuerza el rico país. Los Sapallas impotentes se redujeron inmediatamente a la esclavitud sin oponer la menor resistencia al invasor. Durante numerosos años, los Sapallas, resignados a aceptar su triste destino, trabajaron sin descanso para sus dueños Karis. Un único hombre, el joven Choque, último descendente de los jefes Sapallas, rechazaba esta soberanía y prefería recibir los terribles castigos de los Karis que de rebajarse a trabajar para ellos. Los Sapallas intentaron muchas veces convencer al joven hombre abandonar la lucha y aceptar su condición de esclavo, pero en vano. Choque estaba convencido de que los dioses no dejarían impune tal injusticia. Los dioses observaban efectivamente la escena y fueron impresionados por la valentía y la fe de Choque. El gran Pachacamaj tomó la forma de un cóndor blanco y vino al encuentro del joven hombre. El dios recompensó Choque indicándole el sitio de semillas de una planta aún desconocida para los hombres llamada papa (patata). Estas semillas fueron sembradas secretamente por los Sapallas en sustitución de los tradicionales cultivos de quinoa y habas destinadas a los Karis. Algunos meses pasaron, y las semillas empezaron a germinar. Fieles a su práctica, los Karis se precipitaron los primeros para recoger todas las hojas verdes y las bahías de la nueva planta. En cuanto a los Sapallas, debían satisfacerse con los restos dejados en el campo, y en este momento no supieron darse cuenta de que las semillas ofrecidas por los dioses habían podido ayudarlos. Pero su sorpresa fue grande cuando descubrieron los fabulosos tubérculos ocultados bajo tierra que los Karis no habían visto. La preciosa comida les volvió a dar esperanza y la fuerza de combatir al opresor. Numerosos Karis que habían consumido las hojas y frutas venenosas de las patatas habían caído enfermos o muertos. Los Sapallas aprovecharon para rebelarse definitivamente y expulsar el último Karis de su territorio. Choque fue elegido jefe de los Sapallas. Estableció una nueva sociedad fuerte y feliz que siguió cultivando la patata con el respeto que se debe a una fruta sagrada de los dioses.

On the origin of the potato in Bolivia

On the origin of the potato in Bolivia

Once upon a time, the Sapallas lived a peaceful and harmonious existence, nature was generous and entirely provided everything each one could possibly need, and the Entente Cordiale with the close countries had made them forget what violence and war meant.

One day, the sudden eruption of a volcano disturbed the harmony of this small apparently perfect world.

The Karis neighbors of Sapallas, who lived in the North near the volcano, were forced to flee their devastated country and to leave the majority of their goods and belongings. Attracted naturally by the richness of the Sapallas territory, Karis used the force to invade the rich country.

The impotent Sapallas were immediately reduced to slavery without opposing any resistance to the invader. During many years, all Sapallas accepted their sad fate and worked without slackening for their Karis Masters. All except one man, a young man named Choque, the last descendant from the Sapallas country leaders, refused this domination and preferred to receive the terrible punishments from the Karis rather than to work for them.

Many times, the Sapallas tried to convince the young man to give up the fight and to accept to be enslaved, but in vain. Choque was convinced that the Gods would not leave unpunished such an injustice. The Gods observed indeed the scene and were impressed by Choque’s bravery and faith.

One of them Pachacamaj took the appearance of a white condor and came down earth to meet the young man. He rewarded Choque by showing him a place where seeds of a plant called papa (potato) were stored.

This plant was still unknown to mankind. The Sapallas started in secret to sow the potato seeds, replacing the traditional cultures of quinoa and broad beans which were only reserved for the Karis. A few months passed, and the seeds started to germinate.

As usual, the Karis immediately rushed to collect all the green leaves and bays of the new plant. The Sapallas had no other choice than picking the remainders left on the fields, and it was still not clear in their mind what was the benefit of having utilized the holy seeds.

However, it was a great surprise for when they later discovered fabulous tubers hidden under the ground which had been missed by the Karis. This invaluable food gave them hope and new strength to fight against the oppressor. Many Karis who had consumed the potato leaves and their poisonous fruits suddenly fell sick or died.

The Sapallas organized their rebellion and definitively kicked the Karis out of the country. Choque was elected as the new Sapallas chief. He set up a new happy and strong society, and potatoes continued to be cultivated with respect as a sacred gift from the Gods.

Potatoes are in the nightshade family (genus Solanum) and like tomatoes, eggplants and other species in this family, they contain a toxic glycoalkaloid, called solanine. They are concentrated in its leaves, stems, sprouts, and fruits which protect the plant from its predators and the mythical Sapallas people from slavery…

The extents of Myths, History and Folklore of papas in the Americas are hardly to be seized here, there is still much more to discover.

~ ○ ~

Keep exploring:

Works Cited & Multimedia Sources

- rewritten by N. Brachet, based on the book: Leyendas de mi tierra. Antonio Diaz Villamil. 1926.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Axomamma

- Wikipedia: Potato.

- The Vanishing Aymara Potato Tradition

- https://cipotato.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/AN28852.pdf

- https://www.cultivariable.com/instructions/references#NRC_1989

- https://cipotato.org/potato/native-potato-varieties/

- https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/quechua-guardians-potato